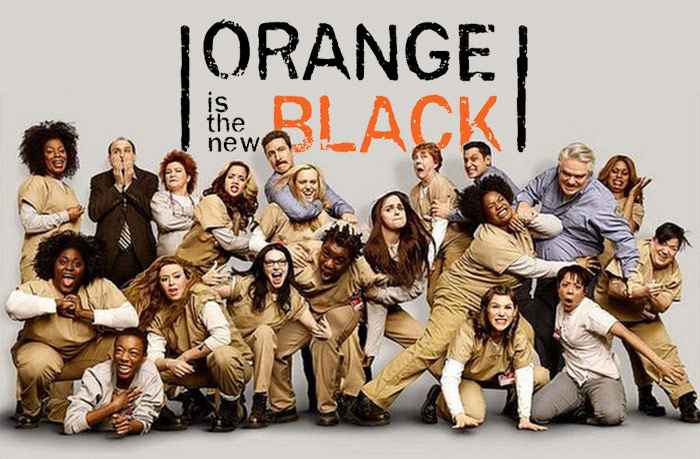

Utopian Relations: Intersectionality in ‘Orange is the New Black’ and ‘Black Mirror’

Romantic, sweet, slightly childish and seemingly never-ending – this is the type of love that plays the role of an immediate attention grabber, a rating booster that keeps us anchored in front of the flat screens, daydreaming and craving for more. Everyone who has watched Black Mirror‘s San Junipero and/or is familiar with Brook Soso and Poussey Washington’s relationship in Orange is the New Black knows what I am talking about.

With millions of fans all over the world, those two series are deep, thought-provoking and a constant reminder of the vices and virtues overflowing our everyday lives and contemporary society. The first one achieves this by showing us a grim alter reality where modern technology exceeds its controllable limits in human life, the second by introducing the present-day struggles (and triumphs!) of marginalised people in an honest and outspoken manner.

One thing that stands out when drawing a comparison between the two shows, is the different modes of representing sexuality, and the underlying subject of intersectionality (a vital element in modern feminist theory). By looking closer at those two cases, I wish to elaborate more on the idea that both programmes present different angles on the same issue – the place of intersectionality and desire in a utopian world.

The Utopian Impulse

In his book Cruising Utopia, José Esteban Muñoz reminds us of philosopher Roland Barthes’ words that ‘the mark of the utopian is the quotidian’ and goes on to explain that ‘such an argument would stress that the utopian is an impulse that we see in everyday life’. 1 It is tempting, therefore, to question this utopian impulse with regards to its intersection with other aspects of everyday life. Undoubtedly one’s lived experiences depend on a vast spectrum of social characteristics which combine, but are not limited to, sexuality, gender, race, age and class under the umbrella of a single identity. This is by no means to say that one’s identity can be treated as a monolithic whole. On the contrary, those ‘identity differentials’, as professor Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw claims, are registered as ‘particular components that exist simultaneously with one another’. Moreover, they are also shaped by and are subject to various forces – forces which are outside of a person’s subjectivity and which are dictated by a long cultural and socio-political history. An in-depth examination of those factors would entail a methodology that not only takes this intersectionality into account, but places it centre-stage.

First and foremost, it is crucial to clarify the use of the terms intersectionality and utopia throughout this article. The first term is concerned with the correlation of certain minoritarian constituents that determine the different experiences of oppression within dominant organisations, the second one links with the first in the way it stages a sort of creative imagining that breaks away from those dominant orders, or explicitly critiques them.

In the following analysis I will aim towards establishing a critical approach towards the representation and interrelation between sexuality and other identity traits in the two aforementioned television series. It is important to note that they exist in a predominantly Western context with specific socio-political environments – the United States and the United Kingdom. The narratives from Orange is the New Black (hereby referred to as OITNB) and Black Mirror serve as exemplary cases of the current tendency in the television industry to turn towards a more inclusive, broad and open politics of representation. I will consider the role ‘utopia’ plays in them in order to demonstrate the way in which the importance of intersectionality is revealed (or concealed).

Similar in Difference

The couple from San Junipero – Yorkie (portrayed by Mackenzie Davis) and Kelly (Gugu Mbatha-Raw), and the characters of Poussey Washington (Samira Wailey) and Brook Soso (Kimiko Elizabeth Glenn) from OITNB exist in rather different narratives and therefore engage in two distinct types of utopia. Nevertheless, both examples make strong critical arguments on their use of intersectionality and carry rich potential for disruption within the domain of heteronormative ideas of sexuality.

I wish to begin by pointing out the similarities between the two case studies, which will foreground their crucial dynamics in this direction. Both couples are same-sex and interracial with one partner being black, the other white or Asian (but passing – as – white). Both relationships are based on a deep commitment, passionate desire and romantic love for the other. Both narratives are set up in an other space. In the case of San Junipero this is a completely fictional world, the afterlife which is made accessible through modern advancements in technology. In the case of OITNB this other place is the Litchfield prison – one much more real, yet, I dare say, still primarily unknown to the presumably anticipated spectator of the show. This enables them to engage with the issues they depict in a more liberated way, speaking openly and allowing for a discussion outside of their narratives’ boundaries. More intriguingly, both stories carry the motive of death – either as a springboard or as a crucial event.

Socio-political arrangements play an indispensable role in the construction of every individual’s lived experiences, especially in terms of their sexuality. On the one hand, those arrangements form groups which enable individuals to establish a sense of community and which allow for self-identification. On the other, those influences can be not only positive and useful, but in many cases harmful and oppressing as well. The romantic relationships in the cases examined here transgress those characteristics to a certain degree and formulate a specific utopian quality that subverts the dominant power structures in the contexts they exist in.

Philosopher Ernst Bloch makes a critical distinction between abstract utopias and concrete utopias. The main difference being the way in which they (dis)engage with the historicity of social, cultural and political endeavours. Muñoz explains that ‘abstract utopias falter for Bloch because they are untethered from any historical consciousness’ while ‘concrete utopias are relational to historically situated struggles, a collectivity that is actualized or potential.’ 2 I, however, argue that both types of utopia examined here carry significant possibilities for the creation of social attitudes in terms of studying sexuality and its intersectional points of resistance.

Brook and Poussey

In OITNB the couple realise their relationship in a distinctly hostile surrounding. The utopian elements of their relationship are evident in the way they create a safe space for themselves in which to enact and live their desires and their love. However, those utopian elements belong to the realm of concrete utopias as the characters are alert to the different factors influencing their relationship. Instead of shying away, they launch a conversation about those factors, thereby coming across as aware and more sensible.

The realities of their condition subject them to offer a rationale for the establishment of their intimacy which began towards the end of the third season. In its final episode (Trust No Bitch), Poussey and Brook become closer and later develop an intimate relationship which is predicted by Poussey’s exclamation that ‘blasian is beautiful’. Using the word blasian – which is a mix between the words black and Asian – she points the audience’s attention towards the importance of race for their relationship. Soso is gradually accepted at the black girls’ table, although Poussey’s friends object to it at first.

In the prison, the women divide themselves as belonging to separate groups, each group is determined based on race, ethnicity, age, religion or other background. The acceptance of a non-black person in the black girl’s group presents a disruption in the hegemonic order within the prison. This disruption is made possible thanks to the sexual and romantic desires of a member from the group – Poussey’s friends accept Brook because she is her girlfriend. This is another indication towards the complex dynamics encompassing people’s socially performed identities.

The need to determine and explicitly pinpoint one’s sexuality and gender is another aspect that the couple cunningly illustrates and talks about. While Poussey is openly lesbian, in Power Suit Brook claims that she is ‘attracted to people, not genders.’ Although she does not lay claim to a particular term, I am led to believe that her sexual orientation is pansexual – she can presumably develop physical attraction, love and sexual desire for people regardless of their gender identity or biological sex. However, this revelation is enveloped by the harsh realities in which they exist in as Brook expresses doubts whether their relationship would be possible in the outside world.

This takes us back to the utopian qualities of their relationship when the romantic momentum is somehow sustained despite the ongoing mayhem at the prison. In The Animals, the couple sneaks in the improvised time machine in the laundry room where they start planning their future together, wishing to stay away from the advancing commotion. Unfortunately, at the end of the episode we see officer Baxter Bayley (a white, young male) tackling Poussey to the floor, in the midst of what was supposed to be a peaceful protest, to the point where she is no longer breathing. Her death sets various effects in motion and breaks the utopian illusions so far constructed within the couple’s life. The fact that Poussey’s character, a black, young lesbian, is destined to such a fate is fundamentally grounded in the oppressive legacies of white supremacist history which marginalises such identities. In the case of OITNB, however, this is not necessarily the case. It is important to bear in mind that television media has a long history and its very own ontology which need to be considered. As Jane Arthurs argues in her book Television and Sexuality: Regulation and the Politics of Taste:

Producers may be informed by audience research, but they also act on embedded assumptions about who is watching, what kind of programmes they like and what forms of address are appropriate. […] Television emerges, then, as a complex set of localized and historically specific practices that are produced out of changing definitions of its audiences and purposes. 3

This points to the fact that representation of various marginal identities in film and on television is predominantly regulated by an established system of taste. Such systems often favour a subject with whom most of the audience members would supposedly identify with. In the beginning of OITNB this was essentially the young, middle-class, white woman (portrayed by the character of Piper Chapman) who, as the creator of the show Jenji Kohan explains, was being used as a ‘very easy access point […] relatable for a lot of audiences and a lot of networks looking for a certain demographic.’ 4 However, the system regarding a target audience is questioned and challenged further in the series using characters who act as some sort of catalyst for the disruption of those ‘embedded assumptions’. This disruption is made possible exactly in cases such as Poussey and Brook’s relationship. Instead of guiding the spectator through an expected point of view, they take the dominant stance by positioning queer people of colour’s lived realities centre-stage. This is the reason why Poussey’s death is experienced as a profoundly devastating, tragic outcome, regardless of the other characters’ (or the viewers’) identities.

Kelly and Yorkie

The idea of death being a tragic event is completely overturned in the story of Yorkie and Kelly from San Junipero. The relationship between the two characters at first seems naïve and childish – they are presented as young, showing a strong attraction to one another and always meeting at a night club. San Junipero is later revealed to be a simulated reality the elderly can live in after their physical death in the outside world. Towards the end of the episode the audience also understands that in the real-life Yorkie has been paralysed since she was twenty-one – she crashed her car after coming out as a lesbian in front of her parents who reacted poorly because of their embedded beliefs. This shows that death is actually desirable because the afterlife seems like the only opportunity for her to live a free life, express her true sexual desires, independent of the restrictions imposed in the real world.

We also understand that Kelly had a husband and a daughter, both of which have died without uploading themselves into the virtual world. Those pieces of information gradually construct a richer background for the development of the couple’s intimate bond. Despite that, the story does very little, if anything, to explicitly comment on the importance of race and age to sexuality throughout the plot. It seems as if those factors are of no importance to the development of their relationship. This is the reason I see San Junipero as belonging to the abstract kind of utopias – the episode finishes with the couple ending up living happily ever after (in the afterlife), driving off into the sunset under Belinda Carlisle’s 1987 hit song Heaven Is a Place on Earth.

On one occasion, the women do have a conversation about their sexual desires, yet not relating those desires to other forces affecting them can result in questionable, unfavourable circumstances. Such undermining of intersectionality could be ineffective and prejudicing especially in the case of Kelly, who is a black female and is sexually non – conforming to predominant beliefs and conventions. This can pose a certain issue as, according to Harry Benshoff and Sean Griffin,

‘being a black female means dealing with both patriarchal assumptions about male superiority and lingering ideas of white supremacy’ and moreover – ‘being a lesbian of color might mean one is triply oppressed – potentially discriminated against on three separate levels of social difference.’ 5

Not engaging with those potentially discriminatory practices, the narrative risks becoming a part of their circulation in the dominant milieu. Furthermore, ‘when it goes unmentioned, whiteness’, as well as heteronormativity, ‘is positioned as default category, the center or the assumed norm on which everything else is based.’ 6 This is evident in the strikingly submissive, homonormative way in which the couple chooses to enact their love – Kelly proposes to Yorkie and later they have an improvised wedding. Their monogamous relationship and the marriage are traits considered to be a fundamental ingredient of heteronormative relationships. Going back to an analysis of the media, it could be said that the episode is negotiating between the desire to represent minoritarian stories and the need to satisfy the presumably predominant taste of the audience for a loving, fulfilling relationship with a romantic happy-ending – the recipe for a sustained homonormative narrative, oblivious to other affecting factors.

Underneath the seemingly unrealistic story-line, there are some important arguments that could be extracted, nevertheless. By staging a fictional environment, San Junipero might serve some other beneficial purposes such as accommodating for a discussion, unbound from indoctrinating beliefs and authoritative ideologies. The abstract utopia, after a deeper analysis, reveals great potential in its relatedness to the critical imagining of a different future. The metaphorical world of the afterlife is a place where important aspects of one’s identity, such as race, age, ethnicity and class, do not hold the same rigid positions in the subject’s social life. Therefore, I understand this life-after-death as an allegory for a new queer future created after the death of heteronormative doctrines and the white supremacist thinking that goes along with it, in other words – end of the repressive powers that dominate today’s society.

Effects

In this brief analysis I strived to observe the interplay between sexuality and other identity traits with regards to the utopian qualities of two definite narratives from OITNB and Black Mirror. The chosen examples demonstrate crucial aspects of intersectionality as a critical approach in reading creative works made for a television context. The main objective was to bring the two narratives together in order to juxtapose them and examine some of the underlying mechanisms used to depict sexuality and intersectionality in Western television nowadays. As Joseph Bristow remarks:

Class, generation, race and sex – just to give some of the main categories for mapping understandings of sexuality – are factors that can complicate our knowledge of how power is distributed in the West. Therefore, it becomes possible to grasp exceptionally complex reconfigurations of dominance and subordination when we explore the interfaces between these multiple coordinates of power. 7

This statement encompasses my view regarding the urgency for an informed study of intersectionality in relation to the understanding of the so-far discussed sexual identities. The differences between the two cases illustrate the possibility for a broader exploration of what television can do in this respect. The episodes clearly evidence the different modes in which they engage with those points through constructing their subject-matter according to (or inconsistent with) the impact of intersectionality on the representation of sexuality. Therefore, supported by the idea of abstract and concrete utopias, the implications of those utopian relations within both series provide a wider potential for cultural and socio-political discourse.

Bibliography

Arthurs, Jane, Television and Sexuality: Regulation and the Politics of Taste (Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2004)

Benshoff, Harry M; Griffin, Sean, America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003)

Black Mirror, created by Charlie Brooker (Zeppotron & House of Tomorrow, Endemol UK, Netflix, 2011 – 18)

Bristow, Joseph, Sexuality (New York: Routledge, 2011)

Caputi, Jane, ‘The Color Orange? Social Justice Issues in the First Season of Orange Is the New Black’, The Journal of Popular Culture, 48.6 (2015), pp. 1130-50

Marshall Cavendish Reference Books, Sex and Society (Cavendish Square Publishing, 2010)

Muñoz, José Esteban, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU, 2009)

Muñoz, José Esteban, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis, MN: U of Minnesota P, 1999)

Orange is the New Black, created by Jenji Kohan (Tilted Productions & Lionsgate Television, Netflix, 2013-18)

‘San Junipero’, dir. Owen Harris, written by Charlie Brooker, Black Mirror, created by Charlie Brooker (Zeppotron & House of Tomorrow, Endemol UK, Netflix, 2016)

Works Cited

- José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU, 2009), p.22. ↩

- ibid. ↩

- Jane Arthurs, Television and Sexuality: Regulation and the Politics of Taste (Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2004), p.1. ↩

- Jane Caputi, ‘The Color Orange? Social Justice Issues in the First Season of Orange Is the New Black’, The Journal of Popular Culture, 48.6 (2015), 1130-50, p. 1132. ↩

- Harry M Benshoff and Sean Griffin, America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), p.10. ↩

- ibid. ↩

- Joseph Bristow, Sexuality (New York: Routledge, 2011), p.155. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

These women are amazing together!

I have watched San Junipero episode at least ten times, and I still am shocked and amazed at how amazing it is every time I watch it.

This is probably, my favorite episode of the entire show.

Everything about this episode is perfect. The direction, the writing, the acting. I love the production value. It takes you in, it makes you feel like, you’re in the 80’s and 90’s. The score definitely helps, the main score is beautiful, you feel the emotions of these two characters.

This episode would not have been the same, had it been anyone else making this. I can’t imagine anyone else playing these characters. Even the side characters are fantastic.

At first all the last episodes of BLACK MIRROR are talking about the bad effect of technology, and how could you deal with it, but here they tried to show the good effect of the technology.

For me, watching it for the second time was like re-watching “The Sixth Sense.”

I’m in love with Poussey because she is a beautiful, strong, sympathetic, passionate but delicate human being and I’m totally in love!

For all it’s excellent work in highlighting ethnic and sexual diversity in OITNB, they still indulge in cripping-up by having an amputee guard played by a non-disabled man.

OITNB balances entertainment and message wonderfully.

First Poussey was saying how she needed a girlfriend and how she was lonely then Soso came around and was depressed and lonely because nobody liked her. Then she overdosed on pills and Poussey found her in the library and thought she was dead. Good thing Poussey is always in there. Then during Norma’s class Poussey stood up for her when she saw the girls praising toast and told them how Soso tried to kill herself and they pushed her away. Poussey was the only one who cared about her. And its sad how they were planning to travel when they got out of prison and go on adventures but now Soso has no one to go with because Poussey died. I feel like in season 5 Soso isn’t going to date again because Poussey was the only one who wanted to talk to her and since she was already depressed and suicidal in the beginning, having Poussey die after they just started dating is going to have Soso feel more suicidal and depressed. Damn this show can really break someone’s heart and have them cry for a long time of they’re really attached to the show.

They were more than just lesbains…they loved each other not just for sex. Poussey just wanted someone to love her and it breaks my heart that she died trying to help someone. Rip Poussey…

San Junipero was quite refreshingly hopeful and for Brooker. It was the most far fetched of them all though, unfortunately! I like that the story wasn’t hurried towards the reveal of what San Junipero really was, which is confident storytelling.

Am I the only person who believes that San Junipero was not leaving cynicism behind? The ending was bittersweet at best if one considers what happens after the end of the episode and completely bleak at worst.

Nope, I agree. Earlier in the episode, there’s a scene set in a hellish underground bar populated by long-term residents who seem desperate for a novel experience – anything to break the monotony of their idyllic existence in “paradise”. I think i’d feel the same way after spending a hundred years reliving the exact same experiences. Fun for a while, but then… It’s a bit like an old Twilight Zone episode – is this heaven, or is it actually hell ?

i love kelly & yorki’s relationship so much!! i also love how other ppl feel the same about kelly and yorkie, they were beyond an episode, their love was greater and all i can do is ask for a spin off.

I adore this show, and this episode was such a change of pace, which you’ve captured perfectly. Love it.

They just need to be in another movie together, gosh >_< I am not fully satisfied!

Omg! The cuteness is over 9000!!

This is a fantastic article — it’s both well-written and thought-provoking. I like your thoughts on intersectionality, and I enjoy that you brought feminist theory into the piece. I also appreciate that you not only chose same-sex couples, but also interracial couples, creating a unique level of diversity. So, thank you for doing such a wonderful job with the thorough representation!

Thank you!

Well researched and nicely written. Although I’ve never seen ‘Orange is the New Black’ and its subject matter wouldn’t interest me, your writing held my attention whilst it addressed some very relevant points. Well done. I confess, though, I am a huge fan of anything Charlie Brooker writes. In the case of ‘San Junipero’, I certainly agree that the sexuality of the female characters wasn’t important – the storytelling was, and such a story would have worked equally well with any sexual orientation. Anyway, thanks for the interesting read.

orange is the new black seems like a pretty good show. I think these two are adorable and I am interested.

This show is so addicting, like the episodes are an hour long but when you finish one they’re a cliffhanger and you feel like you NEED to watch the next episode.

I am not really a crier ( which is funny because my Zodiac sign is a Cancer) but when P died I actually cried my self to sleep! (I’m a baby).

In all honesty I felt a connection with me and Poussey, because the character and I had a lot in common and it really did break my heart to watch her die like that I swear I cried for two days because of it.

San Junipero has been my favourite so far. most of black mirror features things you hope never happen and are bleak and horrid. but what if San Junipero world really exisited? What a great place/tool it would be for people who want to go there – older people, sick people – live your life free of the shackles that may have held you back. i really liked it.

I have to say I though San Junipero was utter tosh. The twist was foreshadowed so obviously you’d have to have never seen a story in any for not to have guessed it. Just found it really, really boring. I know I’m in the minority for this one.

Thank you for writing this Kaya! I saw Black Mirror with a girl who I met some days ago and she is very special to me. Thanks for bring that moment with her again.

I’m finally watching season 6 of orange and I’m still not over this relationship.

If you like OITNB, then you might like HBO’s show Oz, it’s also set in a prison, this time a male prison and it’s darker than Orange, but it does have its darkly comedic moments and a theme of redemption, plus plenty of ship opportunities (canon or not).

It’s uncanny how the episodes of Black Mirror start out one way and end in a completely different direction.

I must say that the ´love story´ is beyond my understanding but it looks like nowadays, one has to keep an open mind on all the tendencies…

When it comes to Black Mirror I like the darker stories, I couldn’t put San Junipero at the top of my list for that reason, but still it is a fabulous watch.

San Junipero… wow. Stunning, really well shot, staged and put together. A bit of hope.

Never watched these shows, but I got goosebumps all over my body. Thank you for the lovely article.

I have never watched either of these shows, but your take on intersectionality really drew me in – excellent article!

The analysis I didn’t know I needed. Great work.

OITNB

OITNB is a great show that encapsulates much diversity and female empowerment whilst at the same time, attends to serious subject matters yet remains entertaining. Great balance.

OITNB depicts present-day societal struggles to a tee. The way they introduced police brutality, ICE deportation, the struggle of finding a job after prison, and the struggle to return to a normal life allows for the viewer to find a common ground with the characters presented. It is something that does not blind viewers from the struggles of our society. Additionally, Black Mirror provides an illustration of what is likely to occur through our advancements with technology. These shows speak on the real, and not on the falsified visions that television tends to provide for viewers.

So so important! Great article

I think it’s cool to think about how differences having the power to unite people in a way

A really interesting read – thanks for this. Loved the use of Muñoz.

Nice read and thorough analysis. Kudos. I especially like the juxtaposition of “utopia” with the penal environment of Litchfield. As you point out, it’s “cunning,” in the best sense.

I think you may now have to add, Beth and Space Beth’s relationship from Rick and Morty with the inclusion of the new season 6 episode lol, very good article👍🏽