William Wordsworth’s Lucy Poems and the Romantic Nature of Abuse

In 2014 several events occurred to provoke conversations into how and why men become abusers. The questions are not new, but for the first time in recent memory the exchanges appear to be part of an ongoing dialog. Dehumanizing treatment of women has longstanding Romantic aspects, which have heretofore made it socially acceptable. Although we balk at such outward displays of misogyny from the likes of Julien Blanc and Elliot Rodger, we support the media and culture that breed woman-haters like them. Western society must stop enabling abusers and justifying their actions; just because misogyny is Romantic does not make it romantic. In his 2007 article, “Loving to Death: an Object Relations Interpretation of Desire and Destruction in William Wordsworth’s Lucy Poems,” Robert J. Walz provides insight into the basic nature and function of abusive, obsessive, and otherwise unhealthy male-female relationships. Mark J. Bruhn writes in “Margaret Atwood’s Lucy Poem: the Postmodern Art of Otherness in ‘Death by Landscape’” that Wordsworth’s use of Lucy as a plot device is pervasive, but redeemable from its misogyny. Using these articles to examine Wordsworth’s Lucy Poems, I then apply the Poems as a lens to examine anti-woman abuse in 2014 and to prove that these vile actions are not only romanticized, but are also Romantic.

Walz asserts that the persona of the Lucy Poems evidences a schizoid personality who has molded the titular Lucy, whether in his imagination or in fact, into an object of obsessive love. This ego wishes to “take the whole object in at once by identifying with it,” and to ultimately consume it, but the ego fears the loss of either identity in the process (24). Bruhn identifies Wordsworth’s Lucy as a representation of both the poet as a child and of his inner femininity. He interprets the Lucy Poems to arrive at the conclusion that “Wordsworth reads the death of the childhood self as essential to the development of the reflective adult mind,” which itself identifies the kinship of particular, identical “something[s]” in both humans and in nature, and these somethings constitute “an ultimate self or being, of god-like proportion” (455). Because Lucy is already so closely associated with nature, to unite with her would allow the poet to tap into this power.

Both Walz and Bruhn rightly read Lucy as the representation of the feminine other. Bruhn argues that “Lucy’s otherness is figured solely in her femininity,” and that she becomes “an alternative, non-traditional identity” (455). For Walz, Lucy is the feminine non-presence in Western society and culture. He writes, “Lucy’s life and death [is a] symbolic representation of the fate of the archetype of the earth goddess. Having been repressed into obscurity, the ghost of the archetypal feminine haunts Wordsworth’s consciousness” (28). Rather than recognizing Lucy’s divinity, however, Wordsworth and the persona instead reduce her to an ignorant and denatured figure.

Both poet and persona fear Lucy’s feminine power. Out of a fear of becoming the feminine other, Wordsworth destroys Lucy’s individuality, and she becomes “a being whose existence and identity ha[ve no] significance other than that which the persona [gives] her” (Walz 27). As an extension of this fight against losing Wordsworth’s—masculine—identity, the “portrayal of Lucy as merging with nature and losing her individuality is the result of the poet’s ambivalence about the feminine and his way of countering its power over him” (30). Because Lucy is synonymous with nature, this avoidance also reads as a fear or rejection of the natural world that Wordsworth is otherwise known for celebrating.

Wordsworth’s treatment of Lucy in this way is identical to Western misogyny in the 21st century. Mainstream culture holds that beautiful women are the ultimate marker of success in a man’s life. They are objects designed exclusively for men’s sexual pleasure. To win a woman, a man must be successful, and his success is evidenced only by material possessions: the expensive car, the large house, the fat wallet. While financial wealth is required to obtain any of these things, woman, as the game lured by them, is the definitive status symbol. Despite their lofty positions as success-markers, women are consistently portrayed as less than human. This paradox is both understandable and inexplicable, but it distills to one simple fact: so long as women are displayed and treated as possessions in mainstream culture, mainstream culture will deny them their humanity.

Othering women greases the wheels of Western misogyny. Men occupy the highest echelons in all fields and institutions, and this gives them the power to dictate which stories are told and which are forgotten; because women are not men, their stories are suppressed. This dynamic is the same across all power-systems: whites suppress black voices; heterosexuals suppress queer voices; middle-aged adults suppress the voices of both youths and the elderly. As a result of othering by the majority, each of these marginalized groups finds itself fighting against negative media portrayals that negate its member-individuals’ identities. This negation of identities and experiences that deviate from those contained in the stories men tell distances the majority further from the minority, to the point that they cannot sympathize with their plights. Women are held to contradictory standards designed by men: standards to which men are not held and which they do not themselves fully understand. And women, whether they submit to or resist these patriarchal molds, remain forever othered because they are not and cannot be men.

The purpose of this oppression—embodied in both the suppression of women’s voices and in the standards to which they are expected to adhere—is to control women. Patriarchy seeks to control each woman’s education, career, sexuality, and appearance. Top-down control methods, such as glass ceilings and anti-choice legislation, are so broad and pervasive that they allow smaller institutions—even down to the individual level—to exert varying levels of control over women as well. In their most sinister form, these individual-level control methods take the forms of rape, domestic violence, and murder.

Whether violent or not, all forms of control over women stem from the same fear of the feminine Wordsworth exhibits in the Lucy Poems. Walz explains:

The schizoid ego fears being devoured by its own hunger as represented in the object and may attempt to disarm the object’s threat …. The ego projects the potentially dangerous object back into the world where it hopes it cannot be dangerous to the ego’s integrity. However, in this position the ego is once again threatened—this time by its perception of threats from the external world—and once again attempts to control this threat by doing to the object what it fears the object will do to it: it attempts to incorporate and annihilate the object through identification with itself. This wish to annihilate, or escape the object is closely aligned with the wish to altogether sever the ego’s dependence on the object by achieving total self-sufficiency. (33)

This statement from Walz deserves further unpacking, as it relates to misogyny from both Wordsworth and the mainstream West. The high priority placed on obtaining the woman-as-object turns women into a source of anxiety for all men; if a man is rejected by his prey, then his success—which is defined by the procurement of a female status symbol—is nonexistent, and his masculinity is jeopardized. Knowing that the object of his desire has the power to disrupt his identity in such a way, the man preemptively rejects her in an attempt to maintain a safe distance from her. But this situation still leaves him without a woman to put on display as a marker of his success, and his fears of the feminine become secondary to his fears of societal rejection and judgment. Reacting to these newfound fears, the man chooses one of two paths, both of which are designed to fully possess and control the woman he previously rejected, and both of which will reinstate his masculinity.

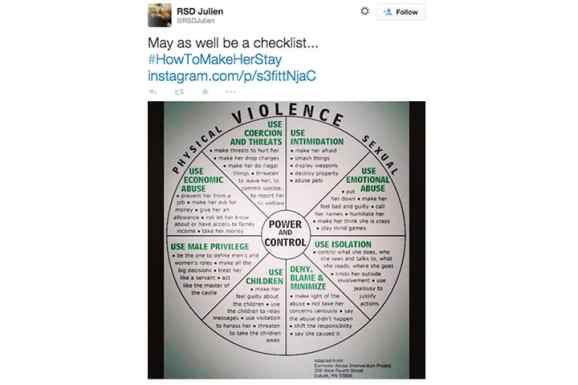

The first path leads to his full possession and control over the woman through manipulation and violence. In 2014 domestic abuse survivors took to Twitter and created the #WhyIStayed campaign to share their stories of coercion, victimization, and disenfranchisement. Among those who belittled #WhyIStayed was Julien Blanc, an influential guru in the Pick-Up Artist (PUA) community, who instructs his students to choke the women with whom they wish to have sex. Blanc uploaded an infographic detailing signs and symptoms of different forms of abuse—such as “DENY, BLAME, MINIMALIZE” and “ISOLATION”—with the comment, “May as well be a checklist… #HowToMakeHerStay” (Blanc). According to Patrick McGuire, Blanc’s “kind of thinking takes the ordinarily offensive mantras of PUAs who try and manipulate women into sleeping with them from the category of creepy, to full-on abuse.” Although Blanc’s social media accounts were closed as a result of the backlash against his anti-woman statements, that he felt confident enough to share them publicly in the first place serves to prove that Western society, at least in some ways, supports his violent, negating, egotistical misogyny.

If he follows the second path, the man fully annihilates the woman, who is the paradoxical source of both his desire and his rejection. In May 2014 Elliot Rodger went on a shooting spree at the University of California, Santa Barbara, killing six people and injuring thirteen others. In the aftermath of the tragedy, it was discovered that a large part of Rodger’s motives lay in his inability to handle being rejected by women and the damage to his masculinity that he believed this rejection caused. In his manifesto, “My Twisted World,” Rodger observes that “[i]t is very interesting to see how this phenomenon works … that males who can easily find female mates garner more respect from their fellow men” (qtd. in Yang). In “What a Close Read of the Isla Vista Shooter’s Horrific Manifesto, ‘My Twisted World,’ Says about His Values—and Ours,” author Jeff Yang asserts that “Rodger’s murderous rage was rooted in … his belief that he was entitled to, and thwarted from obtaining, a trifecta of privileges: race, class, and gender. He saw himself as not quite white enough. Not quite rich enough. Not quite ‘masculine’ enough.” While Yang is certainly correct in attributing Rodger’s actions to intersectional causes, Rodger makes it clear that he targets women because he sees them as lesser creatures who do not have the decency to give him the love his schizoid ego says he deserves. Misogyny was not the sole cause of the Isla Vista shootings, but a blind hatred for women is the reason Rodger cited most often.

Through the same methods of extrapolation mentioned earlier, communities of men may also target women whom they feel have stepped out of line. In August 2014 video game designer Zoe Quinn became #GamerGate’s first target after her ex-boyfriend alleged infidelity following their breakup, resulting in the disclosure of Quinn’s identifying information online: an attack commonly known as doxxing. GamerGaters threatened Quinn with rape and murder, but she was not the only woman to be so targeted. Jenn Frank, a freelance game journalist, retired to write about other things after death- and rape-threats accompanied the backlash against her op-ed, “How to Attack a Woman Who Works in Video Games.” And Anita Sarkeesian, the founder of Feminist Frequency, was similarly doxxed and threatened after she highlighted misogynistic Tropes vs. Women in Video Games, such as: Ms. Male Character, Damsel in Distress, and Women in Refrigerators.

The Women in Refrigerators trope was first identified by comic book writer Gail Simone to describe narratives that are sparked or driven by the murder of the male protagonist’s female love-interest. The women killed in these narratives ostensibly have some value to the protagonist; otherwise, why would he mourn their deaths or seek vengeance? But in the narratives themselves, these women are empty shells whose sole value lies in the display of their tortured corpses. If they remained alive, the audience would have no plot to watch, but their deaths spur on emotion, action, and gritty excitement.

For Wordsworth, then, Lucy’s death is not a tragedy, but a trope. In the Lucy Poems, “[t]he rationale of [the persona’s] abiding affection and imaginative attention … is that the enduring ‘self-presence’ of the existentially absent ‘other Being’ provides the reflective ground for an even deeper, more essential self-recognition” (Bruhn 456). The dead woman is his vehicle to self-discovery. She has no value outside her usefulness to him, because she is an object, not a person. Lucy is a Woman in a Refrigerator, because, were she still alive, Wordsworth would have nothing to write about her.

Works Cited

Blanc, Julien (RSDJulien). “May as well be a checklist… #HowToMakeHerStay instagram.com/p/s3fittNjaC.” Nov 2014. Tweet.

Bruhn, Mark J. “Margaret Atwood’s Lucy Poem: the Postmodern Art of Otherness in ‘Death by Landscape.’” European Romantic Review 15.3 (2004): 449-61. PDF.

Walz, Robert J. “Loving to Death: an Object Relations Interpretation of Desire and Destruction in William Wordsworth’s Lucy Poems.” Journal of Poetry Therapy 20.1 (2007): 21-40. PDF.

Photo credit: “Child Abuse_illustration” by delizm.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Read it for uni and although I’m not one for poetry I did enjoy it. It’s always good to broaden your horizons and I think Wordsworth is someone everyone should read even if you have claimed to have a poetry allergy to get out of it in the past like me.

I’m not a huge fan of poetry, but I liked the general concept of these. I think I’d have to sit down and analyse them yet, to get everything out of them, as one reading isn’t enough.

I have previously read a few Wordsworth, they’re really good.

I felt a lot of his poems were really very long and I find I don’t enjoy these types of poems very much.

William Wordsworth was greatly inspired by nature. No wonder his poems were the most beautiful of all times.

William is notable especially for his lyricism and for his sensitive and simple style … but he is not trivial at least when he is at his best in the greatest of his poems …although he wrote a good deal of bad poetry … yet he is still one of the most great and the most beautiful of all the poets of the English language

I always wanted to read some Wordsworth because I somehow had the idea he was a good poet.

its the life of william wordsworth

Wordsworth is the greatest of all the English Romantics …

I don’t much like poetry.

Wow, awesome analysis. Very well written. I agree, completely.

Thank you. 🙂

Very informative and detailed analysis. I especially liked how well it still relates to modern society. Plus it never really dawned on me how often the “love interest stuffed in the fridge” thing pops up in entertainment media

The Tropes vs. Women series pointed out a lot of instances. And, as this article points out, it’s unfortunately nothing new.

Occasionally the English of the 1800s was beyond me.

Wordsworth’s best poetry.

This was an interesting article, and I feel that it is relevant in the light of such tragedies in recent times.

Daffodils was my favourite Wordsworth poem. After reading 900 pages of Wordsworth, Daffodils is still my favourite of his poems!

i’d like to see a story line wereSuperman & Wonder Woman are put against each other while they are in love, similar to Black Panther & Storm but rather than being in a bigger story have the rift between Supes & WW being the main story like a super powered Mr & Mrs Smith really seeing all the emotions of having to battle someone you love & all the destruction that would go hand in hand with 2 of the most powerful beings in comic books battling it out

I love history post. I learn something new all the time. Thank you!

Interesting article. I work with victims of domestic abuse and I believe the only way it will be properly tackled is to make it a non-gender issue. As long as it is viewed as a female issue it will not be taken seriously. How ironic is that?

It is an issue affecting both genders. While shelters for women and children most certainly constitute a necessity that should not be subject to budget cuts, domestic violence against men is hushed up by toxic masculinity concepts. This means that, unfortunately, the same systems of oppression make violence against women unimportant and violence against men nonexistent.

Excellent analysis. While I do like some Romantic poets (like John Keats and.. .John Keats), a lot of British and American Romantic poetry is not exactly endearing in its treatment of women through fridging them and having the Lost Lenore trope (Poe was an American Romantic, after all). During this time, poetry was seen as a talent mostly exclusive to men, and it certainly shows. Even beautiful, exemplary work inspired or penned by the Romantics tends to utilize women’s sexual abuse and/or death as a motivator for the male narrator. Awesome work on this.