X-Men, an Excluded Universe: the Changing Cultural Indication of ‘the Superhero’

With over 3 billion gross dollars at the Box Office, the X-Men movie franchise has occupied a favourite spot in the recent decade among comic readers and movie lovers. The X-Men, from their charismatic leader, Professor Xavier, to ferocious and turned-villain Magneto, have equally impressed both comic readers and moviegoers, but for some, over the years, the X-Men have become more than just heroes and villains with genetically mutated powers. The creation of two great comic minds, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, in the 1960s, the X-Men comics were not purely a source of entertainment, but rather represented the changing pop culture in post-modern North America and a society which continuously dealt with prejudices, racial disharmony, exclusion and assimilation.

Equally symbolic is the movie trilogy. Based on the 1982 issue called, X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills, from the initial movie trilogy, the films presented the life of mutants and their struggle to be accepted in a society that felt threatened by their existence; not so different from the 1960s’ experiences of many “excluded groups” who felt their human and civil rights violated. This article explores the cultural indication of superheroes, by looking at the X-Men as representation of social prejudice and exclusion. Perhaps, Professor X’s narration in the beginning of the second instalment in the X-Men movie trilogy is the best way to describe the 1960s’ North America when he says,

“Mutants, since the discovery of their existence, they have been regarded with fear, suspicion, often hatred. Across the planet debate rages, are mutants the next link in the evolutionary chain or simply a new species of humanity… fighting for their share of the world? Either way, it is an historical fact: sharing the world has never been humanity’s defining attribute,” 1.

Why A Shift in Perspective Toward Superheroes?

Comics in general in the turn of the century became a source of youth culture transformation, as the younger generation began demanding a different kind of a hero, one who would not only conquer and “tame the savage frontier”, but one who could deal with the contemporary issues facing a consumer driven America 2. The role of superheroes in comics was a “fantasy” in the midst of a post-modern world, which was quickly changing and facing new tensions and conflicts. While the young generation as consumers and fans feared powers of the superheroes, they also “fantasized” to be like them. Superheroes were capable of solving and overcoming problems that the concerned young generation could not easily do so 3.

One of the major creations of the 1960s, Theodore Maiman’s first successful LASER (Light Amplification by the Stimulated Emission of Radiation), revolutionized comic book graphics and significantly increased their popularity 4. In the 1960s, the comic world caught up with the golden age of scientific and technological innovations. Such scientific ideas gave rise to superheroes with technologically enhanced and genetically borne powers (eg. Cyclopes with LASER eyes), but the storylines still reminded the readers of how the characters continuously dealt with common societal concerns like any other “normal” human.

Superheroes, however, were more strong and knew how to be ethical, even when they used violence and force. Superheroes faced discrimination and hatred, yet unlike “us” they coped with it and moved on 5. The early comics, prior to the 1960s, by contrast, were greatly influenced by the ideologies of WWII and the Cold War; thus they promoted “conservative” or somewhat “traditional” ideas that “normalized” various prejudices 6. Therefore, the ‘60s and ‘70s “comics became a site of contestation over the meaning of America” 7. The X-Men were not any ordinary superheroes. They “were born into circumstances beyond their control, thrown into a world they did not choose…[searching] for authenticity and self-hood,” 8. The X-Men comics represented a period of search for self-actualization, civil rights and resistance to old traditional beliefs, a few themes that marked the 1960s in North America 9.

The Uncanny X-Men and Social Prejudice

In America, where close to half of the population consisted of youth less than 18 years of age, ideas of exclusion, civil rights, political oppression, race, lawlessness and class disparity became significant domestic issues 10. Between 1960 and 1968, crimes against persons went up by 106 percent, including hate crimes. It is possible that Lee and Kirby unintentionally wrote about the issues of prejudice and tolerance but, because the X-Men were despised for no reason other than being different, they became “allegories of oppression” 11.

Comic books became a celebration of the common men and their struggle to deal with issues of corruption, greed, violence and discrimination that the North Americans were facing for centuries. For instance, the 1963 and 1964 issues of the X-Men comics, show the mutants working with the government to eliminate evil mutants, but at the same time neither people nor the government treats them like normal citizens. When the team is called to help battle a group of evil mutants, who are trying to invade the U.S. Missile base, the government still does not consider their legitimacy as “rightful” citizens. Not so different in North America, many “minority groups” including blacks, Aboriginals and the Chinese fought during the war, but were still deprived of their citizenship rights 12.

X-Men in an Exclusionary Society

Representation of America as an exclusionary society in the X-Men comics is a dominant feature. Mutants in general have to keep their existence and identity a secret in fear of persecution. In one instance, Professor Xavier tells Jean, “…when I was young, normal people feared me, distrusted me! I realized the human race is not ready to accept those with extra powers! So I decided to build a haven…a school for X-Men 13. Even if they are not always in a state of tension, the human-mutant relations in the “X-universe” are often uneasy and in a state of conflict 14. In one episode, members of the X-Men, Beast and Iceman, save a child from falling off a tall building; nonetheless, the crowed gets angry that mutants were “hiding” among them and become violent. Consequently, Beast (Hank) temporarily leaves the group because he is tired of being discriminated against 15.

Some social scientists have compared the X-Men’s fight for recognition and acceptance similar to the Civil Rights movement and have associated government policies against mutants to Jim Crow laws. While the severity of racism is not exactly the same, hatred, fear and violence are dominant concepts in both cases, such as prejudices against the excluded “others”, which violated civil and human rights 16. For instance, people with Down syndrome have “historically” been prejudiced and put under the care of state, because of their genetic differences with other human beings who were considered “normal” 17. In a similar manner, in the X-Men, the government creates the Sentinels who are programmed to detect and eliminate mutants, because they were considered to be genetically “abnormal”. Deep within, “the X-Men comics are less about superpowers and more about human tendencies to fear and hate those who are different” 18.

The Opposing “other” Superheroes

The concepts of multiculturalism and quest for racial harmony become evident in the series as the writers unite a cast of characters with different ethnic and racial diversity, for example, Canadian (Wolverine), Russian (Colossus), German (Nightcrawler), and African (Storm) 19. It is possible that such bold statements and the comic’s unique “class” of characters resulted in the X-Men never receiving the same popularity as the Superman and Captain America during the ‘60s and ‘70s. While the X-Men spoke of mutant rights, social justice and tolerance, other characters such as the popular Captain America and Iron Man, took part in conflicts that were more conservative and ideologically close to state policies 20.

Within the comic books, Captain America and Iron Man were raised to the status of heroes, while the X-Men were discriminated against. Like Superman, these two heroes dealt with every day social and political issues, but at no point questioned the “integrity” of the federal state 21. For instance, Captain America was created to protect United States from foreign invaders; thus many of the episodes dealt with his duty as a super soldier and promoted the image of an ideal warrior 22. Iron Man, although not a soldier, was wealthy, arrogant and a businessman who profited from warfare by making weapons. Symbolizing the era of Vietnam War, the Cold War, and the creation of defence weapons, Iron Man became an icon of technological change in the American state warfare 23. These qualification and their patriotic images of the “Americans”, made Captain America and Iron Man famous in their time period, rather than the X-Men, who opposed state policies.

A Different Kind of a Superhero As a Cultural Icon

It was not until the 1980s that the X-Men finally came back to public’s attention. John Byrne, who took over the project to organize and re-market some of the failed Marvel and DC comics, believed that the 1960s and 1970s comics were too gloomy. The new comics Marvel created had to be more fun and feel good stories even if they were dealing with real life problems. In the 1980s, the conservative Reagan years called the 1960s and 1970s the eras of unfortunate developments that damaged the American morale and patriotism, a position that Byrne agreed with. Consequently, Byrne and Chris Claremont introduced Magneto’s Brotherhood in the X-Men, which became a major success in the story line. The series still retained its dominant themes of prejudice and toleration, but in the context of a post Cold War and post Vietnam War era. It was not a surprise that the collector’s edition of the comic sold over eight million copies in the 1980s 24.

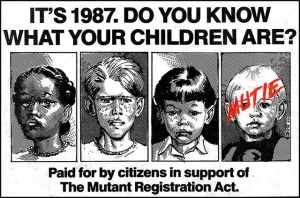

Moreover, this popularity brought the X-Men to film production, by joining the ranks of the Superman and Batman franchises. Twentieth Century Fox began the production of the first movie in 1999, but stayed true to the themes of the comic. The X1 (2000) deals with mutant registration as foreign subjects, X2 (2003) speaks of genetic “correction” and elimination of mutants, and X-Men: The Last Stand or X3 (2006) focuses on a “cure” sanctioned by the state against the mutants. Although there was an uncertainty to the success of the first film in the beginning, given the nature of its themes, the film was a box office success. Lifetime gross success of the X-Men trilogy according to Box Office Mojo is estimated at $607,611,873.00. The first movie’s production was at a budget of $75,000,000.00 (Mojo).

Following the same pattern as the comics, the X-Men films focused on the mutants groups demanding recognition and legitimacy in a society where they belonged. X1 begins its opening scene with Magneto as a young boy in a Nazi concentration camp where he gets separated from his parents and becomes aware of his ability to generate and manipulate magnetic fields. In this scene, director, Bryan Singer shows two things, one that Magneto has come to the United States to live a free life and secondly that he has felt the pain of discrimination and prejudice from the time he was very young. Magneto, like so many others, experiences the reality of the “American Dream”. He feels that the society is not ready for those who are different, like mutants. At the end of the film, symbolically, Magneto is standing on the top of the Statue of Liberty revealing to Rogue,

Magneto: It is a matter of time before mutants are herded off to camps.

Referring to Mystique he says, “I first saw her in 1949, America was going to be the land of

tolerance. Peace.

Rogue: Are you going to kill me?

Magneto: Yes.

Rogue: Why?

Magneto: Because there is no land of tolerance. There is no peace. Not here,or anywhere else that women, children, whole families are destroyed, simply because they were different from those in power,” 25.

In the modern historical timeline, Nazis were not the only regime that discriminated against the “other” ethnic or social groups, although not in the same exact manner. For example, the U.S. sterilization program toward the socially “unfit” was close to Nazis’ policies to eliminate the Jewish population 26. In a similar scenario, the film shows that Senator Kelly proposes the Mutant Registration Act and declares to the president that, “the Mutants are dangerous … why are they afraid to reveal their identity, what are they hiding? We give people license to drive, not to live,” 27.

Mutants are often misunderstood for their powers, assuming that they would hurt other humans. Magneto rightfully states, “Mankind always fear, what it does not understand,” which is a similar fear experienced toward groups such as the Aboriginals and blacks who were often considered a threat to societal harmony and purity 28. Unlike Xavier, Magneto does not see any hope in humankind and it is evident in his actions when he punishes senator Kelly by turning him into a mutant through exposition to magnetic field. After taking his revenge, he points to Kelly, “Who would take you in, now that you are one of us?”. Ironically, Kelly takes refuge in the X-Men mansion in fear of being mistreated by “humans” 29. Here, the filmmakers are showing the ethical and moral behaviour of the traditional superheroes. Even though Kelly advocates mutant registration, the X-Men do not deny to help him. Such types of “social registration” is not unheard of in our own modern world. While registration of Jewish population under the Nazi rule is mostly known, there have been other ethnic groups that suffered a similar faith in North America, of course with different intentions and levels of severity in policies. For example, in 1917, the United States’ government passed an Immigration Literacy Act, which required all immigrants over the age of 16 to register and take a literacy test 30. In Canada immigrants, such as Chinese-Canadians faced head tax and Japanese-Canadians were forced to register in internment camps or else exiled back to Japan during the war years. In recent years, the registration and treatment of the Aboriginals in the Canadian residential schools have been acknowledged officially by the state as an act of genocide.

In addition, the writers in a sense are bringing awareness to the violation of human rights, a problem that historically people of “different” race, culture or ethnicity have faced. In Canada, in the turn of the 20th century, people feared and hated immigrants. The belief that white population possessed more character than blacks, Jews or Natives or even Eastern Europeans was dominant. Racial and sexual purity, according to state regulated policies, became the only acceptable social existence. The Social Reforms Council was created to “control” the unfit, a common policy that is often seen toward the mutants in the X-Men films 31. Also, in 1914, Social Service Congress of Canada declared that the only way to solve the “defective” children issue was to educate or medically “correct” them. The Eugenicists argued that they had a scientific explanation and justification for sterilization in order to modify or stop the spread of the “imperfect” genes. In a way, they justified the exclusion of those who did not fit the state definition of accepted human beings, just as did the government against the mutants 32.

Genetic Mutation and Social Exclusion In Comics

The concept of genetic “correction” appears in all three films. For example, Worthington Laboratories in X3 creates what they call a “cure” for mutants in order to change them to “normal” human beings. While the state claims that the “cure” is only a “voluntary” procedure, most mutants see it as a way to change their identity. For example, Magneto as a Holocaust survivor views the “cure” similar to the sterilization process in the concentration camps 33. In the first film, both Magneto and Wolverine are shown with marked numbers on their wrists. While Magneto was marked in the Concentration Camp, a secret State lab in the United States stamped Wolverine. In one scene, Magneto says to Xavier, “Let them pass the law, they will have you in chains with a number burned to your forehead,” a direct reference to his experiences in the Nazi camps.

Some X-Men, like Rogue, who finds her power threatening to others, agrees to get the cure, but others like Mystique are proud of their own existence. When Nightcrawler asks Mystique in X1, “They say you can imitate anybody even their voices. Then why not stay in disguise all the time? You know, look like everyone else.” To which Mystique responds, “No. Because we shouldn’t have to,”. Mutants do not see their mutation as a threat, but rather as a gift. In another instance, Storm asks Beast, “Why are we still hiding? … they cannot cure us, you know why? Because there is nothing to cure,” (X3). In the same scene, the audience is shown a news broadcast covering protests by mutants and non-mutants against or for the “cure”. A narrator suggests that mutants should be loaded in trucks and cured or maybe the state should declare war on them (X3). However, the X-Men do not give up and try to convince the government to call off the war. A sense of hope is given by Xavier’s speech which declares, “this is a moment, a moment to repeat the mistakes of the past … or to work together for a better future,” (X3), a direct reference to the mistreatment and prejudices toward the exclusionary “others” in the society, and a demand for toleration to create a racially and socially harmonious society.

X-Men and State of Terror

Since the tragedy of 9/11, the films no longer retained their popularity with heroism, but rather explored the existence of the superheroes as a fit image for a world in fear of terrorist attacks. Superheroes again became “cultural icons”, and the new films contained social and philosophical messages to spin a message of hope in a society that was occupied by fear of terrorism 34. The 2003 production of the second X-Men trilogy (X2) deals with the matters of detecting and eliminating mutants. The movie starts with a white house tour guide quoting Lincoln’s inaugural speech, “we are not enemies, but friends,” (X2). One can argue that this is a message pertaining to the discrimination of the state against ethnic groups, such as Arabs and Muslim after 9/11 and a plea for peace. For example, Colonel William Striker uses illegal injections to torture mutants, detain and eliminate them (X2). The President says to Striker, “the last thing we need is a body of a mutant kid at six o’clock news. You arrest, detain, and question, that is it,” (X2). But Striker declares, “We are already in state of war,” a concept that filled the screen images post September 11 attacks (X2). Striker indicates to Xavier that he does not have any problem with mutants as long as he can control them (X2). For example, making a direct reference to Wolverine, Striker holds the same belief until his death when he reveals to Wolverine, “You are just a failed experiment . . . you were an animal then and an animal now,” (X2).

The evolution of Action Comic books marked an era of change and heroism of the common men. While these comics were based on superheroes, the characters lived and dealt with real life issues of a postmodern society. The X-Men comics were created in a time period of dissent and revolution against conformity. It was a time that people demanded civil and human rights. That is what made the X-Men set apart from the other superheroes of their time. The X-Men brought forward issues of prejudice, discrimination and demand for socio-political tolerance. Although it may or may not have been intentional, the X-Men stories criticized past discriminatory policies and asked for change in the future.

The adaptation of the X-Men comics into films began in the 1990s, which was an era of discriminatory attitudes toward the “minority other” due to threats of terrorism. Specifically X2 and X3, speak to government’s discriminatory policies against its own citizens, based on their genetic differences. Storylines aimed to bring awareness to the mistakes of the past, such as genocide, eugenics, discriminatory immigration policies and sterilization. On the other hand, the X-Men are willing to forego the past and look for a brighter future together. While other superheroes were national icons, like Spiderman, or Superman, X-Men had to hide their identity without any masks. X-Men became symbolic in their genetic differences in a society that still is class and racially based. This is the “cultural indication” of the X-Men as modern superheroes.

Works Cited

- X2: X-Men United. Dir. Bryan Singer. Perf. Hugh Jackman, Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. 2003. DVD. ↩

- Wright, Bradford W. “ Superheroes for the Common Man.” Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. 110. Print. ↩

- Loeb, Jeph and Morris, Tom. “Heroes and Superheroes.” Superheroes and Philosophy. Ed. Tom Morris and Matt Morris. Illinois: Carus Publishing Company, 2005. 11-20. Print. ↩

- PBS. “The Sixties: Moments in Time.” The Sixties, the Years that Shaped a Generation. Public Broadcasting Corporation, 18 July 2013. Web. http://www.pbs.org/opb/thesixties/timeline/timeline_text.html. ↩

- Loeb, Jeph and Morris, Tom. “Heroes and Superheroes.” Superheroes and Philosophy. Ed. Tom Morris and Matt Morris. Illinois: Carus Publishing Company, 2005. 17. Print. ↩

- Smith, Matthew J. “The Tyranny of the Melting Pot Metaphor: Wonder Woman as the Americanized Immigrant.” Comics and Ideology. Ed. Matthew P. McAllister, Edward H. Sewell, Jr. and Ian Gordon. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc., 2001. 129-150. Print. ↩

- Dittmer, Jason. “Fighting for Home: Masculinity and the Constitution of the Domestic in the Tales of Suspense and Captain America.” Superheroes of Film and American Culture. Ed. Lisa M. Detora. North Carolina: McFarlen and Company Inc., 2009. 96-116. Print. ↩

- Kavadlo, Jesse. “X-Istential X-Men: Jews, Superman, and the Literature of Struggle.” X-Men and Philosophy: Astonishing Insight and Uncanny Argument in the Mutant X-verse. Ed. William Irwin, Robecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009. 38-49. Print. ↩

- Dittmer, Jason. “Fighting for Home: Masculinity and the Constitution of the Domestic in the Tales of Suspense and Captain America.” Superheroes of Film and American Culture. Ed. Lisa M. Detora. North Carolina: McFarlen and Company Inc., 2009. 96-116. Print. ↩

- Scarmmon Richard M., and Ben Wattenberg. “The Social Issue.” America in the,60s: Cultural Authorities in Transition. Ed. Roland Lora. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1974. 241-256. Print; Smith, Matthew J. “The Tyranny of the Melting Pot Metaphor: Wonder Woman as the Americanized Immigrant.” Comics and Ideology. Ed. Matthew P. McAllister, Edward H. Sewell, Jr. and Ian Gordon. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc., 2001. 129-150. Print. ↩

- Lyubansky, Mikhail. “Prejudice Lessons from Xavier Institutes.” The Psychology or Superheroes: An Unauthorized Exploration. Ed. Robin S. Rosenberg and Jennifer Canzoneri. Dallas: BenBella Books, 2008. 75-90. Print. ↩

- Lee, Stan (w), Kirby, Jack (p), Reinman, Peter (i) and Rosen, S.(l). “Marvel Masterworks.” The X-Men v1 #1-10 (Sept. 1963- Jun.1964). California: Marvel Comics, 2003. Online view, Google Books. Web. http://books.google.ca/books?id=rrPK4vdfBO0C&printsec=frontcover&dq=x-men+1963&hl=en&sa=X&ei=w0brUZSaB4WSqwG_uoDACQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false. ↩

- Lee, Stan (w), Kirby, Jack (p), Reinman, Peter (i) and Rosen, S.(l). “Marvel Masterworks.” The X-Men v1 #1-10 (Sept. 1963- Jun.1964). California: Marvel Comics, 2003. Online view, Google Books. Web. http://books.google.ca/books?id=rrPK4vdfBO0C&printsec=frontcover&dq=x men+1963&hl=en&sa=X&ei=w0brUZSaB4WSqwG_uoDACQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false. ↩

- Lyubansky, Mikhail. “Prejudice Lessons from Xavier Institutes.” The Psychology or Superheroes: An Unauthorized Exploration. Ed. Robin S. Rosenberg and Jennifer Canzoneri. Dallas: BenBella Books, 2008. 75-90. Print. ↩

- Lee, Stan (w), Kirby, Jack (p), Reinman, Peter (i) and Rosen, S.(l). “Marvel Masterworks.” The X-Men v1 #1-10 (Sept. 1963- Jun.1964). California: Marvel Comics, 2003. Online view, Google Books. Web. http://books.google.ca/books?id=rrPK4vdfBO0C&printsec=frontcover&dq=x-men+1963&hl=en&sa=X&ei=w0brUZSaB4WSqwG_uoDACQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false. ↩

- Lyubansky, Mikhail. “Prejudice Lessons from Xavier Institutes.” The Psychology or Superheroes: An Unauthorized Exploration. Ed. Robin S. Rosenberg and Jennifer Canzoneri. Dallas: BenBella Books, 2008. 75-90. Print; McWilliams, Cynthia. “Mutant Rights, Torture, and X-Perimnetation.” X-Men and Philosophy: Astonishing Insight and Uncanny Argument in the Mutant X-verse. Ed. William Irwin, Robecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009.99-106. Print. ↩

- McWilliams, Cynthia. “Mutant Rights, Torture, and X-Perimnetation.” X-Men and Philosophy: Astonishing Insight and Uncanny Argument in the Mutant X-verse. Ed. William Irwin, Robecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009.99-106. Print. ↩

- Lyubansky, Mikhail. “Prejudice Lessons from Xavier Institutes.” The Psychology or Superheroes: An Unauthorized Exploration. Ed. Robin S. Rosenberg and Jennifer Canzoneri. Dallas: BenBella Books, 2008. 75-90. Print. ↩

- Lyubansky, Mikhail. “Prejudice Lessons from Xavier Institutes.” The Psychology or Superheroes: An Unauthorized Exploration. Ed. Robin S. Rosenberg and Jennifer Canzoneri. Dallas: BenBella Books, 2008. 75-90. Print. ↩

- Thomas, Ronald C. “Hero of the Military-Industrial Complex: Reading Iron Man through Burke’s Dramatism.” Superheroes of Film and American Culture. Ed. Lisa M. Detora. North Carolina: McFarlen and Company Inc., 2009. 152-166. Print. ↩

- Wright, Bradford W. “ Superheroes for the Common Man.” Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. 1-29, 287-291. Print. ↩

- Dittmer, Jason. “Fighting for Home: Masculinity and the Constitution of the Domestic in the Tales of Suspense and Captain America.” Superheroes of Film and American Culture. Ed. Lisa M. Detora. North Carolina: McFarlen and Company Inc., 2009. 96-116. Print. ↩

- Thomas, Ronald C. “Hero of the Military-Industrial Complex: Reading Iron Man through Burke’s Dramatism.” Superheroes of Film and American Culture. Ed. Lisa M. Detora. North Carolina: McFarlen and Company Inc., 2009. 152-166. Print. ↩

- Wright, Bradford W. “ Superheroes for the Common Man.” Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. 1-29, 287-291. Print. ↩

- X-Men. Dir. Bryan Singer. Perf. Hugh Jackman, Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. 2000. DVD. ↩

- Lyubansky, Mikhail. “Prejudice Lessons from Xavier Institutes.” The Psychology or Superheroes: An Unauthorized Exploration. Ed. Robin S. Rosenberg and Jennifer Canzoneri. Dallas: BenBella Books, 2008. 75-90. Print. ↩

- X-Men. Dir. Bryan Singer. Perf. Hugh Jackman, Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. 2000. DVD. ↩

- X-Men. Dir. Bryan Singer. Perf. Hugh Jackman, Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. 2000. DVD. ↩

- X-Men. Dir. Bryan Singer. Perf. Hugh Jackman, Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. 2000. DVD. ↩

- Ong Hing, Bill. “Translate This: The 1917 Literacy Law.” Defining America Through Immigration Policy. Temple University Press, 2004. 51-61 Print. ↩

- Valverde, Mariana. “Racial Purity, Sexual Purity, and Immigration Policy.” The History of Immigration and Racism in Canada. Ed. Barrington, Walker. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc., 2008. 175-188. Print. ↩

- McLaren, Angus. “Stemming The Flood of Defective Aliens.” The History of Immigration and Racism in Canada. Ed. Barrington, Walker. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc., 2008. 189-204. Print. ↩

- Kavadlo, Jesse. “X-Istential X-Men: Jews, Superman, and the Literature of Struggle.” X-Men and Philosophy: Astonishing Insight and Uncanny Argument in the Mutant X-verse. Ed. William Irwin, Robecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009. 38-49. Print. ↩

- Housel, Rebecca. “Myth, Morality, and the Women of the X-Men.” Superheroes and Philosophy: Truth, Justice and the Socratic Way. Ed. Tom Morris and Matt Morris. Peru, Illinois: Carus Publishing Company, 2005. 75-88. Print. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I started reading comics in the mid-1970’s. I had a subscription to the Uncanny X-men during the late 70’s and early 80’s. The John Byrne, Dave Cockrum, and Terry Austin period. It was empathy with feeling alienated and misunderstood like an X-man that drew me to the series. Nightcrawler was my favorite.

Good take-down of the subject.

I am glad you enjoyed the read.

The principals behind the stories are fear and discrimination and then definitely resonates with us.

Yes, these issues are more relevant now than even with the political situation around the world.

Mutants are POWERFUL. They are, in fact, MORE powerful than their oppressors. They can fight back if they’re attacked on the street (I can’t), they can intimidate people away when they’re threatened (I can’t). I want to be a mutant.

The one thing that X-Men writers have done very well over the decades is gradually adjust their allegorical themes to fight the prejudice du jour.

Absolutely, I did not included the new films and recent comics as it required more research, but yes, the themes have been relevant to different issues and different time periods.

Comic book fans could be seen as a minority group based on their interests. I have often been called, in high school, by other Mexican teens, “an Oreo” or “coconut” (brown on the outside, white in the middle) because of my interests in this culture and other interests not popular amongst most Mexican teens.

During the initial creation of these popular comics (the ones from the first half of the 20th ce), having a Hispanic, East Asian, black etc. character would have been a political statement, that maybe was not the intention (or goal) of the creator. Not that its an excuse to not embrace diversity, but if one is not actively engaged in, or trying to take a political stand on something, then it’s some what understandable that they would not go through that trouble.

Super fun to be discussing issues and representation in comics like this.

What is the appropriate balance between fearing what mutants are capable of and keeping their abilities in check, and not discriminating against them? How can the average person protect himself/herself from the person with superpowers without going too far in his/her attempts to protect himself/herself.

Great observation, and yes, this is struggle of balance is shown throughout the films and the comics. The line between ethics, freedom and humanity is crossed often and difficult to maintain that balance.

Very well written and well researched article.

Thank you.

X-Men history is complicated.

Our country can end the human war tomorrow by teaching our young ones self-love and acceptance of others.

You bring up some excellent points, a few of which I recently addressed my essay.

Thank you, and yes, I enjoyed your article. It was very informative.

Seeing Wolverine grinning over a pile of slaughtered Afghans a few months after 9/11 pretty much cemented my thoughts that the X-Men’s tolerance only extends to “approved” minorities.

I don’t recall the story that you’re referring to but I have to believe that has more to do with a writer’s and/or artist’s interpretation rather than the intent of character. Think about it this way: Grant Morrison introduced Dusk, a Muslim character in a burqa, in early to mid ’02. And, IIRC, Jason Aaron’s first Wolverine story, “Get Mystique” shows Logan attacking a group of individuals who are bigoted towards Muslims.

Parkinson,

May be you can point me issue # of the comics you are referring to. I am curious to have a look. Thanks

A great article!! Excellent quality of work. I always look forward to your articles.

Thank you Munjeera, I will try to live up to the challenge and provide insightful pieces.

I think it would be really interesting to read a comic about male characters who are simultaneously insane comic superheroes, and also people who are re-examining conventional assumptions of masculinity. Does anything like this exist? Does anyone have any recommendations?

Fred, a very interesting idea. I have read a few books that speak of conventional assumptions of masculinity and it would be interesting to analyze them in the context of comics. Perhaps you can introduce this as a new topic and someone may right on the subject matter.

Perhaps it speaks more to our own society that we always have some sort of fight going on.

Where the hell are the X-Men when we need them the most?

Some really thought-provoking points raised here, although as a longtime X-Men fan, I’m not sure I fully agree with your conclusion.

Muoi, I am glad that you enjoyed the article. The issues I presented here are complicated. We all often have conflicted feelings and diverse opinions about what comics try to represent and what we see in them. I respect your opinion. Thank you for the comment.

We may not have mutant powers but no minority does.

X-Men is a story that was meant to represent all minorities and outcasts, all of the early stories show many parallels with racism, homophobia etc and that’s what makes it a good metaphor. I’d say that it represents LGBT the best in this day and age.

In some ways, it is not only about mutants or as your comment says minorities having power, but it is about what they can offer the society. Take our own society for example, migrants who come from other countries can contribute in a great extent to our economy, yet they are often accused of taking jobs that supposedly belong to the majority.

The X-Men is as good as mainstream comics gets when it comes to an allegory for the minority experience (which in this day and age is honestly kind of sad), but it’s still =deeply= flawed and very obviously the product of people who largely haven’t had to deal with the kind of discrimination they portray in their stories.

At the time the X-Men were created (1963) much of the country, and perhaps all of the country that had comics, was white. The point of the comic was to have the white majority see themselves as the minorities being discriminated against because of birth.

That is a very good point. I did not think of it this way when I was writing, but absolutely agree.

Thanks for the thoughtful post.

I am glad you enjoyed the read.

The comics have actually done a pretty good job of addressing these topics.

This is interesting, especially given the role of X-Men (or lack thereof) in the new Deadpool movie.

I guess the directors have to make a choice on what they can include, same as we do with our articles. To me X-Men characters are a bit more on the serious side, which may not have suited Deadpool and the way the film has been made.

The X-Men remained Marvel’s favorite franchise by retooling their image to be the discrimination that society faced at that time.

The X-Men are perceived to be a threat to humanity due to politics. They are threat to the status quo and through government manipulation the people fear them. It’s almost like McCarthyism. However, the mutants are being treated differently for inherent or physical differences like racial minorities in public.

The discrimination against them is not about competence. Some of the humans think that humans advantage is their intellect over the “savages” called mutants.

The X-Men history has sexuality, broken families, genocide, apartheid, “ethnic” cleansing, and bias towards their own. It is very complex.

Absolutely. Historically in different time periods we have dealt with one or all of these issues at some point.

Diversity is about as much a fictional idea as the Xmen themselves.

That is true. In some societies the idea of diversity is accepted and promoted as a form of cultural pride, but in reality, assimilation of different groups in the society has always been a challenge.

Great article! I fully agree with all of your points.

The storyline with the legacy virus which was a lot like AIDS, small ghetto communities like Aphabet City, the manefestation of powers around puberty, and the fact that some mutants can pass for “normal” while others can’t is reminiscant of the gay community.

Yes, you are absolutely right. This is the beauty of this storyline. You can make the relevancy to so many different issues. At the same time it is upsetting that we are still dealing with such matters.

I love this article – I always get goosebumps when reading or watching x-men just from the relevance it has in society. As someone who falls outside of the accepted mainstream the representation and solidarity x-men gives me is honestly powerful

Thank you. I enjoyed writing this piece. The relevancy to our own real human history or even our modern society was so close that I had to pick and choose my comparisons. Sadly, the storyline is more relevant than ever.

Great article. I never realized how people were made to be more accepting of Superman or Spiderman. I like that you covered the X-men trilogy and the comics.

Thank you, Jenny. I am glad you enjoyed the article.

Such a great article! I enjoyed reading it.

Thanks Nilab. I am glad you enjoyed.

Your bibliography is impressive.