Literature Versus Science? The Cautionary Tales of Scientific Malpractice

Our current way of life undoubtedly owes itself to centuries of scientific and technological advances. However, these developments have always been met with resistance. Often, this opposition arises from the fear of a new invention’s potential to have severe real world consequences. From the Luddite Rebellion in the early 1800s, to the anti-social media movements arising today, resistance to developments has always occurred.

A fictional sci-fi world; the possibilities of science fuel the imagination!

What is interesting, however, is how this opposition to science and technology has played out in literature. There is a shared and often unspoken belief that science and art (including literature) are adversaries or, at the very least, binary opposites. A poem published by Lord Byron in 1819 shows the artist’s disdain for technology:

“This is the patent-age of new inventions

For killing bodies, and for saving souls,

All propagated with the best intentions;

Sir Humphry Davy’s Lantern, by which coals

Are safely mined for in the mode he mentions,

Tombuctoo travels, voyages to the Poles,

Are ways to benefit mankind, as true,

Perhaps, as shooting them at Waterloo.”

Lord Byron, ‘Canto the First’, Don Juan, 1819.

Byron’s work is unmistakably pessimistic. The poet believes that, despite being created with good intentions, new and revolutionary inventions are not beneficial to humans.

Considering the context of his poetry, Byron could be forgiven for his brazen closed-mindedness. Lord Byron was a Romantic, and a prominent one at that. The Romanticism movement developed in response (not in opposition, as is often thought) to both the Industrial Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment. Those who championed Enlightenment turned to reason and scientific study. Romanticists, however, believed in the importance of literature and art alongside the sciences. The Romantic movement was not anti-science, it merely questioned the authority it had gained within society during the eighteenth century. Byron clearly did not entirely agree with his peers on this point.

A famous Romantic painting by Casper David Friedrich. This image glorifies the natural world.

One topic that the Romanticists were preoccupied with was the natural world. In an era of increasing industrialisation, a connection to nature was linked to morality and virtue. It is from this celebration of the environment that Romantic nature poetry became so common. ‘Nature’ did not merely denote landscapes, though. It also encapsulated ideas of natural humanity and the free expression of emotions. Human individuality was perceived as ‘natural’ and, therefore, desirable.

It is understandable, then, that the Romantics were anxious about Enlightenment’s rationalisation of nature. Seeing both humans and the environment as modifiable entities threatened the values that the Romantics held sacred. With science at the forefront of progression, the sanctity of the natural world was being uprooted. Though humanity has moved on from this point, the anxiety of tinkering with what is ‘naturally’ human still remains contentious today.

There are numerous examples of literary works that do not match Byron’s outright negativity. This includes texts from the same time period as Byron. Rather than negate all potential benefits of new sciences and technology, many novels instead offer their readers several cautionary tales. That is, a tale in which the story’s complications are used to preempt future actions that may prove harmful. These tales discuss the potential impact of misusing science and taking new technologies too far. Science and technology are not just tools — their very presence has a transformative power over humanity. Thus, literature has often approached this idea by posing ethical questions pertaining to experimentation and research.

The genre of science fiction (sci-fi) lends itself brilliantly to this. It offers a convenient space to explore the ‘what-ifs’ of scientific and technological development. Authors of the genre are given the creative space to hypothesise what might happen if we as humans begin creating life, relying upon automatons, or altering our brain structure to create super-humans. These ideas play out in the sci-fi cautionary tales written by Mary Shelley, Philip K Dick, and Brian Caswell. As this article will go on to discuss, each of these novels can be broken down into a series of life lessons. They depict extreme sci-fi scenarios, some of which are not entirely outside the realm of possibility, to make pointed arguments. All three authors utilise their literary platform to caution against the misuse of science and technology.

Frankenstein

Published in 1818, one year before Byron’s poem, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein 1 explores the misuse of science. The novel is believed to be the first ever work of science fiction. Despite having origins within the same era as Byron, and Shelley’s husband being close friends with the poet, Frankenstein sends a different message.

The novel follows the story of Victor Frankenstein. He’s an enthusiastic young scientist who grows obsessed with his dream of giving “life to an animal as complete and wonderful as man.” After toiling for almost two years, Frankenstein succeeds. He bestows life upon a creature who is dehumanised from beginning to end, as he is never given a name. The creature’s name is not, in fact, Frankenstein, a detail often forgotten in popular culture.

Things take a frightening turn, however, when Frankenstein realises what he has done. So blinded by his desire to be a trailblazer in this field, he never considered the potential implications of his work. He is at once disgusted by the being that he manufactured with his own hands. Frankenstein chooses to abandon the creature he has created. A ‘man’ now scorned, the creature enacts revenge upon his creator, destroying all that Frankenstein loves. Shelley uses this devastating conclusion to warn scientists to truly consider what they are doing before they make groundbreaking discoveries, not afterwards.

Scientific Carelessness

An idea prominent throughout Shelley’s novel is that of negligent scientific practice. Frankenstein’s work is sloppy from the outset of his experiment. Obsessed with his end goal, he cuts corners to speed up the process:

“As the minuteness of the parts formed a great hindrance to my speed, I resolved, contrary to my first intention, to make the being of gigantic stature, that is to say, about eight feet in height, and proportionately large.”

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein.

If Frankenstein’s creature were of normal human height, undoubtedly it would have been less of a threat. The scientist acknowledges that his first instinct was to make the creature of regular size. To have acted in defiance of that is a clear example of negligence.

Almost as soon as the being was created, Frankenstein ran away from it. He reflects that he was “unable to endure the aspect of the being [he] had created.” So he runs, initially just out of the room, and eventually outside and down the street. When he returns, the creature is gone. Frankenstein makes no attempt to find the being. Having been shunned by mankind, including by his own creator, the manufactured being is angered, resulting in his ensuing revenge.

Ultimately, Shelley’s message is to say that the tragedies that unfolded were avoidable. Had Frankenstein taken the time to make his creature responsibly, then nurtured him properly, he likely would not have killed. The story is set up so readers will sympathise with the creature and condemn the scientist.

Expressing this idea is where Shelley most obviously deviates from her poet peer, Byron. The creation itself is not inherently bad for mankind. It has simply been made so through the neglect of the scientist. There is potential for him to be good. After spending time observing the DeLacey family, the creature claims to sincerely love them. He fears being “an outcast in the world forever” and just wants a friend. It is the scientist’s lack of care that causes the novel’s complication.

The High Price of Scientific Curiosity

A significant motivation for Frankenstein’s experiment is mere scientific curiosity. The idea of chasing fame is touched upon, however, it is clear that the scientist wants to create a life just to know it is possible. While this curiosity, in and of itself, is not a major issue, it is the high price that he is willing to pay that Shelley disapproves of.

The unintended consequences of Frankenstein’s curiosity are numerous. This includes the previously mentioned irresponsibility. But, it also resulted in the declining mental health of the scientist, and had he not intervened, could have potentially triggered world domination.

Frankenstein’s own health is compromised by his work. So determined to complete his creation, he locks himself inside. The seasons change before his eyes, but so consumed by his work, he fails to notice. It is upon the creature’s completion that the scientist truly suffers, though. He suffers from a rather dramatic episode where he exclaims, “the human frame could no longer support the agonies that I endured, and I was carried out of the room in strong convulsions.” His condition is precarious, causing his family to worry. Frankenstein seems irreparably damaged as he claims to be “more miserable than man ever was before.” Shelley is clear in demonstrating that this was all an unintended outcome of his desperate curiosity.

Frankenstein was not the only person endangered by his curiosity, though. The creature kills several people, of whom the scientist loves, and frames another with murder. It seems that the creature truly has the potential to “make the very existence of the species of man a condition precarious and full of terror.” Of course, the scientist realises this entirely too late. By this point, scientific curiosity has already won.

The idea that humans should be careful with scientific curiosity is a product of its time. In 1768, fifty years prior to the publication of Shelley’s classic, Joseph Wright of Derby painted ‘An Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump’. As can be seen in the painting, a scientist is using a bird as a test-subject. Two of the figures are looking away or looking concerned. As for the other figures — the scientific curiosity wins out over those emotions. This is at the expense of the bird’s well-being, which everyone seems to have forgotten amidst the excitement of the experiment.

This appears to be Shelley’s point, too. Had Frankenstein earnestly considered the repercussions of his experiment, rather than blindly following curiosity, the story would have ended differently. But, the central warning is expressed by Frankenstein himself, who tells his friend, “learn from me, if not by my precepts, at least by my example, how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge.” He knows better than any other person that scientific curiosity can lead to horrific outcomes. Shelley’s Frankenstein is clear in persuading eager minds to be cautious with scientific curiosity, and to act responsibly to avoid harm.

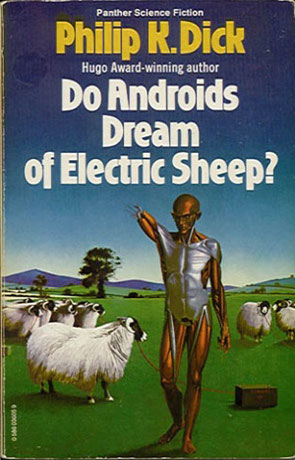

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

More than a century after Frankenstein’s publication, humans had created technologies that Shelley and her peers could not have fathomed. These include the implantable heart Pacemaker, lasers, the Picturephone, and Spacewar!, the first computer video game. These inventions of the 1960’s could have potentially provided inspiration for Philip K Dick’s famous sci-fi novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?. 2 Published in 1968, Androids combines robotic technologies and space travel to create a bleak outlook of the then distant 1992. Also worth noting, later editions of the novel pushed this date back to 2021.

Set in an apocalyptic society where planet Earth is now uninhabitable, the novel follows protagonist Rick Deckard. World War Terminus has obliterated the normal way of life. The only way for humans to survive in this world is to emigrate to another planet. The incentive? “Under UN law each emigrant automatically received possession of an android.” This “android servant” was designed to serve as the “carrot” to encourage citizens to leave Earth. Deckard remains on Earth and is hired to kill, or rather ‘retire’, six escaped and dangerous androids. If this sounds familiar, it might be because the 1982 film Blade Runner, directed by Ridley Scott and starring Harrison Ford, was adapted from this novel.

Surprisingly, however, it is not the vaguely defined, civilisation-ending war that Dick’s novel cautions against. Instead, he focuses on the devastating potential of robotic technology.

When Technology Turns

The complication of Androids arrives when scientists create an android so realistic, so almost-human, that controlling them is near impossible. The “Nexus-6 brain unit” of these machines is capable of responding to stimuli within .45 seconds. So cleverly programmed, they are able to adequately respond to unique situations in the same way a human would.

This provides Dick’s first cautionary message — once a technology is developed or a discovery made, it cannot be undone. In discussing the Nexus-6 androids with his colleagues, Deckard concludes that “we had better just accept the new unit as a fact of life.” If humans continue to create technologies smarter than ourselves, they will become an irrevocable part of society. This includes the risks they may pose.

In Dick’s fantasy world, the machines do pose a great risk. An entire police division is created to monitor and control these man-made beings. This is where Deckard enters. He is hired to hunt and kill six escaped androids. It is understood that these particular Nexus-6 models are dangerous. In fact, the bounty hunter before Deckard was hospitalised by one of them. The job of the bounty hunter is portrayed as one of utmost risk.

The androids in Dick’s novel are not merely cruel antagonists, though. Their supposed ‘evilness’ arises from the conditions inflicted upon them by humans. The Nexus-6 models are programmed by their creators to have a two year life expectancy, intended to be lived entirely as servants. Knowing this, the escaped beings crave more. They crave a long life and they escape to pursue that. Also, Rachael Rosen is seen as something of an android exemplar. However, even she displays a kind of villainy. Towards the novel’s conclusion, she throws Deckard’s goat off the roof of his high-rise building. This goat is the new pride and joy of the bounty hunter’s life. This, it seems, is an act of revenge. She is hurt by his act of killing her android friends.

Thus, Dick is clear in warning readers of the potential for technology to ‘go bad’. Even when created with good intentions, if the technology is intelligent enough, it can turn on its creators. It is important to acknowledge, however, that Dick is not only warning that artificial creations can become a danger to society. He is also warning that humans will ultimately decide if this danger will happen, even if inadvertently. This, then, leads to the question of their status as living beings.

Are Robots People?

Perhaps more pertinent to Dick’s novel is this question of humanity. At some point, his novel argues, humans are going to have to consider the humanity of the beings they create. If we are headed in the direction Dick is suggesting here, we are going to have to accept that we are equal.

Hence, the novel’s title. Dick describes a world where owning mechanical animals is commonplace. This is as real animals are almost completely extinct. Owning large farm animals is a sign of status. Humans in this world certainly dream of owning electric animals, but do the androids share the same desire, the same dream? From the novel’s outset, the author is posing this existential question.

Empathy is seen as the one uniquely human quality. It distinguishes us from other species. In Androids the machines demonstrate empathetic behaviours. Roy Batty is depicted as the novel’s antagonist. He is the evil ring leader of the escaped androids. But even he feels empathy. When his android wife, Irmgard, is retired by Deckard, Roy “let out a cry in anguish.” He exhibits a very human reaction to the murder of his wife.

The bounty hunter’s job is complicated by the androids’ ability to either emulate or possess empathy. Within Dick’s fictional universe, the Voigt-Kampff Personality Test is the only test that can detect androids. It tests for empathy. Having misidentified android Rachael Rosen, it is discovered that the Nexus-6 models can pass this test. The lines between human and machine are blurred irreparably by this.

A thought-provoking interaction occurs between Deckard and Luba Luft (an android). This occurs while Deckard attempts to use the Voight-Kampff test to determine whether or not she is an android:

“An android,” he said, “doesn’t care what happens to another android. That’s one of the indications we look for.”

“Then,” Miss Luft said, “you must be an android.”

Philip K Dick. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?.

Luba’s response stops the protagonist, and readers, in their tracks. This is not insignificant, as the androids in Dick’s novel often act more ‘human’ than Deckard, the killer. Dick is again toying with the idea that robots and humans may one day be indistinguishable from one another.

Even Deckard, hired to kill these beings, struggles with his job. He recognises that they are people, if not strictly human. He must imagine them as dire threats in order to make his occupation “palatable.” He eventually falls in love with Rachael who he knows to be an android. Throughout the book, Dick continually hints at this closeness of human and machine.

It is fair to assume that, for many humans, being seen as equal to an artificial being would not be comfortable to accept. While not overtly critical of doing so, Dick warns readers that this may one day be necessary. If these androids can live the same life that a human can, should they not be afforded the same rights and protections? This will only happen, however, if humans create the technology. Moreover, a failure to consider the humanity of these intelligent machines, Dick argues, could be the deciding factor in these beings’ decision to either help or damage society. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? serves as a cautionary tale, asking scientists to consider the potential existential repercussions of their creations.

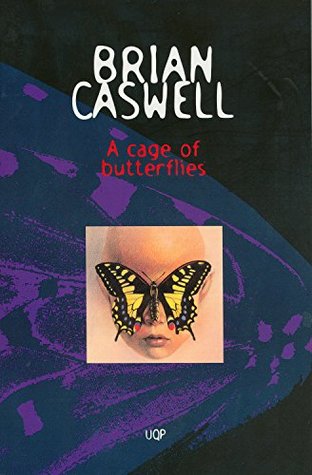

A Cage of Butterflies

“With Larsen in charge … They probably pull the wings off butterflies and record the screams.”

Brian Caswell. A Cage of Butterflies.

This sentence, in a nutshell, is the premise of Brian Caswell’s 1992 novel, A Cage of Butterflies. 3 The story focuses on a group of teenagers with incredibly high IQs. These teenagers, who struggle to socialise in the outside world, live in a research facility together. Here, they are able to coexist with like-minded people. It is mentioned that they are also sometimes exploited for their intelligence. For this reason, the teenagers refer to the facility as the ‘Think Tank’. This seemingly amicable facility proves to be just a facade so that ‘evil’ scientists, Larsen and MacIntyre, can carry out a secret study.

The subjects of this study, who are also the butterflies mentioned in both the title and the above quote, are a small group of ‘babies’. The ‘babies’ are, in fact, not babies, but children seven years of age. Due to a brain mutation, they age incredibly slowly and bear the physical appearance of a child much younger. However, their brains advance faster than the brains of ‘regular’ humans. They are suspected to have developed in this way as the result of a drug their mothers were given during pregnancy. This theory is mostly speculative throughout the novel, and no definitive conclusion is drawn.

The babies cannot speak, but they can communicate telepathically. They are also of higher intelligence than most humans. Larsen and MacIntyre are determined to understand this condition and are willing to cause harm to the babies in order to find the truth. The teenagers from the Think Tank, with the aid of two friendly staff members, Susan and Erik, take it upon themselves to rescue the babies. The babies are saved from a life of being examined, prodded, and experimented on.

As a novel that is often included in English curricula, A Cage of Butterflies provides an important lesson in an accessible format. Caswell is cautioning readers against a ‘success at all costs’ attitude in scientific study. His message is clear — humans are humans, and do not deserve to be experimented on for someone else’s gain. He warns against practices which are unethical and immoral.

Humans as Pawns

Similar to Doctor Frankenstein, Larsen and MacIntyre are obsessively curious about the condition that afflicts the babies. This obsession is so severe that the pair are willing to cause significant harm to the children just to get answers. As a former colleague of the scientists has to explain to Larsen, “they’re kids, not lab animals.”

The most heartbreaking example of this mistreatment is when one of the babies, Ricky, is injected with Sodium Pentothal. Larsen suspects that the babies are able to communicate telepathically. To test his theory, he injects Ricky with the so-called ‘truth serum’. The other babies are sedated at this time so that Ricky is ‘isolated’. Larsen intends to get Ricky to tell him everything. Susan, a staff member at the institute and an ally to the babies, explains the drug:

“In small doses it removes the conscious inhibitions. Makes it harder to hide your thoughts. The idea is that you can’t keep secrets. That’s why they used to use it to try to extract confessions from suspects. Larsen obviously figured he could get information out of Ricky.”

Brian Caswell. A Cage of Butterflies.

As a consequence of this, the child remains unconscious for several days. Even the other babies are unable to ‘reach’ him telepathically during this time. Larsen was cognisant that these children had unusual brain structures. Therefore, it was entirely careless of him to act in such a way when he could not possibly predict the outcome. Instead of considering their well-being as humans and children, he acted purely to get answers.

Despite being scared by this event, Larsen refuses to change his ways. As the teenagers reflect, “if you think Larsen’s going to leave them alone now, you’re off your tree!” To the scientist, Ricky’s prolonged unconsciousness was not the result of the drug. He convinces himself that it is simply “another manifestation of the syndrome.”

Caswell is critical of this mistreatment of people. He continually paints the scientists as the antagonists. The author cautions readers against mistreating people in the field of medical science. He stresses that research needs to be ethical. Perhaps, if Larsen had treated the babies well, his study would have had a more successful outcome.

Another example of humans being used as pawns is demonstrated in the doctor’s abuse of power. Larsen actively toyed with the emotions of the mother of two of the babies (a set of twins). He misrepresented his intentions with the children, claiming “I can promise the best of care and expert attention.” Readers know this to not be true, however, as his intention is never to care for them. When the mother asks about visiting her children, Larsen uses false amicability to dissuade her. He states, “visits can be easily arranged. But, to be blunt, in cases this severe they can be quite depressing.” He is intentionally deceitful, and abuses his power as a medical professional, to keep her at bay. He knows that prying eyes may jeopardise his study.

Caswell is clear in his disdain for the character of Larsen. In doing a most rudimentary ‘who wins and who loses?’ reading of this novel, Caswell’s contention could not be more overt. The two staff members, Erik and Susan, and the Think Tank teenagers are all rewarded at the novel’s conclusion. They, who continuously treated the babies as humans and not test subjects, were wealthy and happy by the novel’s conclusion. This is in direct contrast to Larsen who loses everything. Most notably, his one chance for fame and every piece of research that could help him obtain such glory. More than this though, he loses his job, his reputation in his field, his boat, and his family (he’s divorced and has no contact with his only daughter). Being unable to treat his patients as humans ultimately leads to Larsen’s downfall.

Fame and Global Repercussions

The novel’s location is never expressly stated — but one might hypothesise that it looks something like this.

An idea underpinning all three novels is that a small, isolated experiment has the ability to cause global consequences. However, this is worth discussing within Caswell’s text due to the subtle way in which he expresses this. Unlike the ambiguous, yet populous, locations of the previous two texts, A Cage of Butterflies is set in a small rural area. Of the location of the facility, readers only know that it is somewhere near Sydney, Australia. Aside from the characters in focus, there is very little acknowledgement of any other people within a contactable distance. Consequently, it is jarring to read that, within Caswell’s story world, the happenings in this insignificant little place have the potential to alter global societies.

Larsen is chasing fame and glory. He wants to be widely known and revered for his work. He does not want to help the babies live a life in which their condition is understood. He wants to understand their condition to be credited with the discovery. “He smiled. They would name the discovery after the discoverer. Larsen’s Syndrome. It had a nice ring to it.”

More disturbing than the scientist’s greed are his long-term intentions. Noting that the babies’ condition was caused by a drug taken by their mothers, Larsen ponders:

“A means of producing genius and telepathy through an inexpensive pill … And the mother needn’t even know what she’s been given … Every Defence Department in the world would buy it.”

Brian Caswell. A Cage of Butterflies.

As the Think Tank kids ponder themselves, “if they can create a race of super-genius telepaths…states will be able to think of a thousand ways of using them.” Individual human rights would be in jeopardy if Larsen and his parent company were to go through with this plan. Yet, Larsen does not care. He is too concerned with the millions of dollars and the potential Nobel Prize he could gain from this. Caswell does not need to explicitly state that this attitude is wrong — this is presented as nothing more than unthinkable callousness. Readers are made to feel disgust towards Larsen.

Unlike the previous novels, no devastating outcome is reached. The world is not altered and nobody is killed. There is no terrifying precedent to be learned from. Caswell’s lesson, instead, arrives with the fate of Larsen. He lost everything that meant anything to him. Larsen lost the power he did have, and ends up at the mercy of those he was once in command of.

The novel concludes, then, with the Think Tank teenagers, the rescued babies, and Erik and Susan creating their own company. This company covers numerous sectors and capitalises on the individual genius of each member of their chosen family. Greg (a Think Tank teenager) employs Larsen as the Head of Research in their endangered species organisation. These underdogs conclude the novel with all of the power. However, what they do with this power is an important distinction made by the author — they do not abuse it as Larsen did. It is in this conclusion that readers get a sense of Caswell’s message. He uses A Cage of Butterflies to warn against acting unethically within the medical science field. He presents a possibility for what might happen when scientists fail to think about the consequences of their inhumane actions. Most overtly, Caswell stresses the importance of considering the well-being of every patient, study subject, and, more generally, every human.

The cautionary tales that each novel has presented are still applicable into the 2020s. It can be safely assumed that, for all three authors, they could not have fathomed the scientific and technological progress that humans have made thus far. As one example, the intelligence of smart phones today was likely unimaginable, certainly for Shelley in the 1800s. But even for Dick and Caswell writing in the late twentieth century, humankind’s reliance on smart phones might have seemed a kind of hybridity, melding human and computer together. This idea certainly befits the science fiction genre. For this reason, the lessons of these novels are, perhaps, more pertinent today.

Those lessons each author presents can be succinctly summed up in few words: use science and technology, but do so responsibly — exercise caution always. Unlike the previously mentioned Byron-esque cynicism, these authors are not anti-science. They merely wish for technology to be used thoughtfully. As previously discussed, the Romanticists held anxieties about maintaining ‘natural’ humanity. Shelley exhibits this in her novel, a clear product of its time. But more than a century later, Dick and Caswell are presenting readers with the very same anxiety. Scientists have the ability to alter what it means to be human. That power, suggests each author, demands the utmost care and thoughtfulness.

A factor that should not be overlooked is where these texts, and their cautionary lessons, originated. Each novel discussed here is a product of the Western world; the authors are from England, The United States, and Australia. Underlying these identified themes, then, is the Western ideal of ‘progress.’ Science and technology have long been intrinsic aspects of this ideal. ‘Progress’ suggests that a society should always be moving forward; that advancement is how humans will thrive. When it comes to scientific or technological developments, though, these authors stress that it is possible, and dangerous, to unthinkingly move too far forward.

These three novels are a far from comprehensive list, of course. Undoubtedly, there are countless texts who express the same values. Regardless, these unique novels do offer a glimpse into literature’s use of the cautionary tale as a pre-emptive response to scientific malpractice. Literary scholars have argued that literature is a window through which readers can observe a fragment of culture and its associated beliefs or values. This very idea suggests that readers should continue to listen to the authors who stress caution. After all, these novels demonstrate that the world may depend upon it.

Works Cited

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Lovely to see this piece up! It’s remarkable how humanity can have the same conversation about what it is to be human repeated in different ways over the centuries. I also loved how you cleared up a common misconception about Romanticism being opposed to the Age of Enlightenment/the Industrial Revolution (rather than being a reactionary stance). It’s a reasonable expression of caution when “progress” seems to be hurtling forward at breakneck speed, perhaps with blinders on.

I took a class on Romanticism last semester and one of the first things I remember being told was that the movement was not opposed to Enlightenment. It is easy to see how people would perceive both ideas as dichotomous, though. But I completely agree, as I was writing I could not help but note the relevance that these older texts have to today’s use of technology. Thank you for your kind feedback! 🙂

Great work, especially the Frankenstein section. I know Frankenstein is considered horror, but for me, it was one of the saddest books I’d ever read. The idea that a human would create someone only for their own gain, and then put that creation through hell just to prove a point…playing God in the worst way.

Thank you! I completely agree with you. The scene where the creature tries to approach the DeLaceys is heart-breaking. After observing them for so long he feels genuine love, but Frankenstein’s carelessness means he’ll never be loved back. Before I had read the book, I never thought it would take that kind of turn. It’s nice to see someone with as much enthusiasm for this little book as I have!

Yes! Feeling or being unloved is the worst feeling in the world. That, not monsters or vampires or things that go bump in the night, is the real horror. I think some horror and mystery writers still “get” that, but I also think we lost some sense of gravitas when people like Mary Shelley left this earth.

I wish people would appreciate the authors of these books a lot more during our generation.

As do I. Mary Shelley was a genius and that’s all there is to it. And that’s coming from a person who is not by any stretch of the imagination a horror reader. (I wasn’t allowed to read it as a kid, avoided it as a teen, and didn’t read any until Frankenstein was required in college Brit Lit. Glad I read that though, because it’s a great, cool book).

Well, from the perspective of literature fans, Shelley may not be among the top of their canon, from the world of the fans of horror and sci fi she is one of the all time greats. One of the great pioneers.

Only Edgar Allen Poe and Bram Stoker are on the same level in horror and there is really no one seen as quiet so high on the literature stakes in Science fiction. Look at how the works of truly great writers like HG Wells and Jules Verne are seen today, childs\young adult adventure stories. Wells was an incredibly well respected political writer in his time.

Indeed, those are all great writers. And may we never forget the fiasco that was the War of the Worlds radio broadcast in, was it 1937?

H.P. Lovecraft is the probably the only horror writer to have a sub genre of horror named after him. You’ve heard the term a Lovecraftian horror. Lovecraft was mostly inspired by Edgar Allan Poe, but I’ll bet he was also influenced by Shelley and Stoker. Herbert West -reanimator was one of Lovecraft’s short stories which was definitely based on Frankenstein and I’d say the Stoker’s The Lair of the White Worm was also an influence because there are elements of that in some of his stories. When it comes down to the modern Sci fi/Horror genre both Shelly and Lovecraft are big influences because they more or less that both genres could work together.

The spark that brought Frankenstein’s monster to life was Mary’s imagination… she was influenced by many things, I’m sure.. her miscarriages… and babies dying.. the arrogance of her husband and his friends… the idea of what is ‘creation’ and who owns it… The scientific advancements of her day… the failures of medicine (her own mother died because doctors knew nothing about bacteria and cross infection, though how aware she was that she had been killed by ignorance I dont know).

All of these things and more will have influenced her…

Yes! And she did a great job of expressing that in fiction.

Lovely read. Can I recommend everyone read Literary Walks in Bath where it is explained where Mary got some of her ideas, most notably the remarkable Dr Wilkinson of Bath. His laboratory and lecture room was just round the corner from where they were living. But the writing was Mary’s, not Percy. That’s very clear from anyone who has troubled to read her letters.

I’m intrigued, I might have to check this out! Thanks for the recommendation.

It has been known for ages that Percy did some editing and wrote some passages (about 7 percent of the whole text). And that he helped her get it published. But it’s her book.

Intriguing topic. I was at an inaugural lecture some years back by Prof Tim Mole, and not only did he note the Shelleys attending lectures on Galvanism, he also explored a farm in Somerset (can’t remember where, Quantocks I think) which was highly likely to have been visited by the Shelleys, where the farmer was experimenting with Galvanism, and had rigged up loads of copper wiring in the trees, leading to a bunch of batteries in his laboratory.

Actually the book doesn’t really refer to electricity as bringing the monster to life. The method itself is actually not described, and in fact most of Frankenstein’s research is into alchemy, then chemistry.

There is a rather brief reference to galvanism — blink and you’ll miss it — but there are numerous references to other scientific developments of the time that are not actually directly tied into the creation of the monster.

‘Raising the Dead’ by Andy Dougan is quite a good book that covers the work of the galvinists, whilst telling the story of the experiments by Andrew Ure to reanimate the hanged murderer Matthew Clydesdale in Glasgow, 1818.

The star of the Frankenstein has got to be the 1930’s Universal Film Set – the Lab when working is really something to behold – static electricity going up and down pylons – buzzing with a symphonic gusto – gosh, I really loved to watch those scenes culminating in Frankenstein’s creation “It’s alive”. I believe the props for said lab still exist somewhere in a private collection.

Great timing… I am teaching Frankenstein in a lit. methods class this term. Thank you.

I love this article! I wish I’d had this to hand 28 years ago when I studied “Three Gothic Novels” for A level English Literature.

Is there no room for the term ‘futuristic’?

No. Science fiction is a perfectly good name for an existing type of fiction.

I think Scanner Darkly is Dick’s absolute masterpiece, with an emotional depth beyond anything else he wrote.

Then Ubik, Do Androids, Time out of Joint and Martian Time Slip.

I guess it’s the first Dick book someone reads that often makes the most impression, because you’re getting Dick’s whole reality-is-an-illusion trip for the first time. Once you’ve read a few, you do kinda know it’s coming. My first encounter with PKD was Eye in the Sky, not necessarily one of his best but the first couple of chapters in particular are thrillingly disorientating.

I have only read Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, but Philip K Dick is an author who I have been meaning to read more of. This helps me work out which to read next!

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch is another magnificent novel, again reality-subverting in a unique way. There are a couple of other points I always liked about him: (a) his prediction, and loathing, of intrusive targeted advertising; and (b) his heroes are often ordinary people who usually are good at something, they are competent artisans or professionals, who get sucked in by the hallucinatory reality they believe they are engaged in.

Another great one, though rougher in execution, was The Penultimate Truth. I’ve never fully trusted a historical documentary since. And the parallels between Talbot Yancy and Ronald Reagan are disconcerting.

I was going to say the same. I am rereading ‘Three Stigmata’ and it is so relevant to where we are today, with corporations eclipsing governments and the deliberate skewing of reality to control masses of people. ‘The Penultimate Truth’ is a realistic construction of where we are heading as autonomous weapons are unleashed on the world. A number of his books from that period explore the relationships between media, propaganda and government, including ‘We can Build You’, ‘The Simulacra’, ‘Now Wait for Last Year’ and they are all relevant.

I appreciate all of these recommendations! My list of books to pick-up is always growing.

Eye In The Sky is great for the shifts in perspective as different characters take charge of the collective delusion. Well worth rereading.

I have read Shelley’s and Dick’s novels, but never heard about A Cage of Butterflies. Thank you. Will look it up now!

It’s a really quick, easy read. I definitely recommend it to anyone interested in science-fiction!

Science fiction has the means to convey messages, whether political, moral or social, that other genres don’t.

What about literary fiction?

Science fiction is the genre that deals with ideas, their consequences and how they can exist – the latter meaning that there is a considerable amount of world building that goes into science fiction. An hefty amount of effort goes into ensuring that the implications and extrapolations are consistent with each other – a kind of ensuring that the hidden implicit world makes sense. Believe me, as a science fiction writer, the hidden world consistencies have to be worked out, or the work of science fiction quickly falls apart. A good example is Larry Niven’s Ringworld. He had to write a second novel to explain the hidden contradictions his engineer readers pointed out. Does this kind of thing happen in literary fiction?

As literary fiction is about writing style to reflect and give resonance to issues that are known about or can be observed. So the answer to my question has to be no.

Which means that more work has to be done to produce a good science fiction than a good literary novel.

Literary novels will always lag behind science fiction novels when it comes to new ideas. Science fiction novels will always lag behind literary novels when it comes to style and technique to give that extra bit of resonance with the subject matter to the reader. Hence there will always be antagonism between the two groups.

As for the literary science fiction novels, I’ve found them disappointing. They tend to be watered down science fiction and watered down literary. I think this boils down to pace, which in turn finds its roots in the argument above.

My wife and I read Frankenstein about a decade ago and had a wonderful time discussing it. Shelley was a pioneer in every sense, from the intellectual currents of her time to her establishment of an entirely new literary genre. Now, we will read this book together.

Blasting work with this post. I have read Frankenstein a few times and each time I am struck by the one ‘gap’ she never explains how Frankenstein cannot see that his creation will be ugly a horror before being animated and immediately upon animation is repulsed. It’s like magic or something and for me damages the book as a whole.

I completely agree, his sudden change of heart doesn’t make complete sense.

Eight months after she and Shelley met she gave birth to a premature baby girl, whose appearance may have been yellow with jaundice, certainly wrinkled and quite different from a full term baby. Some think that the shock at seeing the yellow eyed monster was inspired by her shock at the sight of her own first baby, who died days later. She spent much of her time while writing Frankenstein pregnant and the theory seems plausible to me. John Sutherland writes convincingly about this in one of his books, I think it’s “Is Heathcliff a Murderer?”

Oh, I never knew that. That’s a really interesting, and sad, theory.

I always thought of it as Frankenstein being so caught up in “can I?” that he never considered “should I?” until it was too late. Hence the sequence he destroys the “bride” at the last moment, unable to bring himself to commit the same sin against nature twice.

An intriguing and ‘enlightening’ read. Thanks. As a follow-up I would recommend reading John Wyndham’s 1955 novel ‘The Chrysalids.’

Thank you! And thank you for the recommendation, too. The Chrysalids has been on my always growing to-read list for a while now, I just haven’t gotten around to it.

Frankenstein is a metaphor for any type of political extremism. It’s Stalinism, Fascism, KKK etc. The creature is monstrous yet sentimental, and so are all these isms…sentimental love for country and origins is at the heart of national socialism.

You may be thinking of the early films rather than the original book …

Stephen King wrote a very interesting theory on the three staples of horror, Frankenstein’s monster being, funnily enough The Monster.

He was of the opinion that the book is about misuse of technology, a more modern take maybe The Terminator.

There isn’t really any ‘science’ in Frankenstein. The building of a man-monster is simply an enabling device, as is HG Wells time machine, or Star Trek’s warp drive. They are not there to be taken literally.

Perhaps you’re right! There’s a plethora of interpretations of Frankenstein that can and have been argued. From the creature being a racialised ‘other,’ to his creation being the product of a nineteenth century man anxious about the fact that women have all of the power to create life. That last one seems a little far-fetched in my mind, but scholars have argued such theories. The fear of science is just another interpretation.

No, it was a literary response to what was at the time cutting edge science and as such engages with that science.

However, it was not so much the physiology and anatomy of the late C18th that interested Shelley and her group. Rather, it was the science of electricity and its percevied role in generating and maintaining “life”. Experiments carried out by the likes of Alessandro volta and Luigi Galvani were of central interest.

The science of electricity fascinated the age and Frankenstein is one take on that. That doesn’t mean, of course, that the science in Frankenstein doesn’t also serve literary purposes. But, like most science fiction, is takes its literary turns from a presupposition of science.One could make a case as well for science itself being a literary genre, further blurring the boundaries between what counts as science and what as literature.

Anyway, great article we have here.

In terms of the themes in Frankenstein, it is interesting to compare Frankenstein with E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Der Sandmann, which was also written in 1816- both rework classic myths into dark visions of the industrial world, both involve scientific hubris and human simalcra.

Cultural theorist Marina Warner argued that aspects of the Gothic- figures such as Frankenstein’s monster- also grew partly out of existential angst following scientific revelations such as the first detailed studies of the cardiovascular system via cadaver examination in medical schools, experiments with blood transfusions, etc.

This article, and several centuries of admiration argue that Mary Shelley does far more than rework classics myth.

I’m not suggesting she “only” reworked myth. Merely listing some aspects which both Frankenstein and Der Sandmann have in common.

Very interesting ideas, but, let’s be honest, Frankenstein is one of the world’s most boring novels.

Having grown up on the Boris Karloff creature, I was very surprised by the literary version when I finally read it.

I didn’t find it boring at all (surprising for me, as apart from Wuthering Heights, I normally dislike ‘classic’ novels and prefer the movie versions) and for the first time I truly empathised with the creature.

I don’t think cinema has ever really done the story justice, but the theatrical version, which gained cinema release as part of the excellent NT Live program, directed by Danny Boyle is the exception.

I’ve never seen a film adaptation of Frankenstein, and it seems I shouldn’t. They don’t seem to be receiving many glowing recommendations.

But I agree, Shelley has done a wonderful job at making readers sympathise with the creature. She’s an excellent writer.

Stanislav Lem said that Dick was the only real American SF writer.

Yes, he rated Dick highly. Dick in his own way repaid the complement by claiming that Lem was in fact not one person but a team of writers due to the amount of ideas there were in his books.

Mary is Frankenstein and Shelley the Creature.

I had to read A Cage of Butterflies for my english class.

I found the beginning very interesting as it captivated me from the alluring prologue, so i read on and then i was introduced to different character portrayed though their POV’s. They were alright but what the author didn’t do was expand on them.

I wanted to know more about the characters, as there weren’t that many of them to begin with but they weren’t that complex, so it was a bit boring to understand them. Can I just say that i absolutely loathe endings to books! That is just the way I am. and my opinion is no different to this book.

I felt that after the climax of the story, the ending was disappointing.

I’ve heard that a lot of people have the same criticism for A Cage of Butterflies. The characters aren’t something I personally noticed when reading, mostly because I was trying to breeze through to learn what happens next, but I can understand the criticism.

I thought the ending was sweet when I first read the book years ago, but re-reading it recently, I’ve decided that I didn’t altogether enjoy the happily-ever-after. Despite that, it’s still one of my favourite books!

To everyone readin this article, I would recommend the Frankenstein book, which is superior to the film versions in every way. For example, the electrical apparati are from the films: in the book, Frankenstein discovers the secret of life, but it isn’t described or explained. The monster is also intelligent, even cultivated: he read Goethe, negotiated with his creator, and only sought vengeance later.

I agree, 100%

Reminds me of the version in the TV series Penny Dreadful. Intelligent, cultivated, later becomes vengeful due to the negligence of his creator and the fact he didn’t do anything to help him become part of society.

Penny Dreadful was great. Well worth a look if you like Victorian Gothic type stuff, vampires, werewolves etc.

Frankenstein borrows heavily from the Golem legend of the Talmud and stories down the ages.

Frankenstein as a name is obviously German-Jewish or meant to convey that. Mary got in early on the Golem literature. Her period saw many such tales written down and it appears folk tales go way back in Jewish tradition. Gods formed Adam out of the Clay in the account of Creation.

Mary is my favourite female author. She was the most intellectual of her merry gang. I remember writing about her knowing al the latest science of the day as it was used in her story.

She lost all her gang when they were young. Must have been very lonely for her after being part of such a vibrant and unique energy. The Romantics were wonderful and a huge never ceasing influence on litrature ever after.

Frankenstein as a name is old German aristocratic and has no German/Jewish implications, never mind the -stein. Also the monster‘s creation is hardly cabalistic in nature, that‘s the Golem. Probably more of a rather ghoulish version of the Pygmalion myth stirred by desire and enlightened science, if that isn‘t magic.

The Golem is a great story. There is a very old black and white version and it was an X Files episode, but I wish someone would do a big screen version. (The Limehouse Golem is not a Golem film..)

Mary Shelly was probably one of the most educated persons in the country having grown up in an intellectual household and so it’s not that much of a shock that she wrote such an important novel so young.

Yeah, definitely. Having Mary Wollstonecraft as a mother probably would have set her up pretty well!

I started reading Dick around the same time I started taking acid in the 70s. It was a fantastic cocktail that allowed me to consider so much more than the swirling patterns on the curtains in my horrible drab bedsit. Meanwhile my friends were all reading Carlos Castaneda. Hah! Did they back the wrong horse!

Thanks for a fine piece – haven’t read these books for like twenty years so good to revisit them with your wisdom.

Ack, Frankenstein. Such a fantastic piece of writing, and multilayered enough to be relevant just about any time since its creation. The context surrounding Mary’s writing of the text is pretty incredible, too – putting up with Percy’s shenanigans…

Yes! Still a great, great book. So pertinent today!

All that Frankenstein says is that after a thorough study of the sciences of chemistry and anatomy he discovers a method for “bestowing animation upon lifeless matter” but he does not say what that method is.

One may as well say that galvanism was an influence on James Whale (or his screenwriter), given that his film was the first adaptation of the novel that we know of in which electrification is used to bring the monster to life.

The book should have been called Frankenstein the Monster. Victor is the monster in the story. The creature just wanted to be accepted.

I could not agree more!

A Cage of Butterflies really is a great journey.

I could not agree more! It’s a short little book that discusses a lot.

It has great issues of morality and ethics.

What Mary Shelley did was to recognise the problems inherent is scientific progress.

Frankenstein’s monster is everywhere today, with surveillance, murder by drones controlled from rooms in Colorado, and people kept alive by machines, rather than being allowed to die.

Thanks for a fascinating article Samantha. Reminds me a small bit of John Sutherland’s take on Frankenstein, in which he showed that Shelley certainly wasn’t conceiving of electricity as an animator for the body, despite James Whale’s classic filmic take involving that.

Thank you for your kind words!

Shelley could not have predicted Hitler or Stalin- which supports Barthes’ claim. The creature has outgrown the fantasy.

Loved Elsa Lanchester in her dual roles as Mary Shelly and the title character in The Bride of Frankenstein.

I would have thought that the reasons why Mary Shelley would write a story about a brilliant but flawed monster created by an even more flawed man who recoiled in horror from his own creation… and with no sign of a female creator in sight as there was none living to be had… would be obvious enough.

I’m wondering how people feel about Kenneth Branagh’s “Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein”, starring Robert DeNiro as “The Creature”? It caused me to actually read the novel for the first time.

I think I may have read the book first but I thought the movie was pretty good.

I’d like to think that the original dispute between science and literature came from those with religious beliefs against those with early secular beliefs.

I enjoyed you article very much, It gave me additional insight to Frankenstein, curiosity towards the book “Do Androids Dream of Sheep” and I did recall the movie “Blade Runner”, but most of all; I desire to read “A cage of Butterflies”. So curious now, like a scientist!

I have never heard of ‘A Cage of Butterflies’, but now know what is on my next read list! It’s an interesting concept of nature vs science, as science has been a fantastic source of our understanding and exploration of nature, including ourselves, but also one of the detriments. Would be a interesting subject in the realm of the modern pandemic, using technology as the most effective way of human communication, aka using technology to bind our ‘nature’ of human interaction.

A good essay. I enjoyed your reference to Byron (my mother’s favorite poet) and how you discussed Frankenstein. Several of your references in your essay I am unfamiliar with, which I now want to look into. Again, a good essay.

Great essay Samantha. Are you familiar with Ellen Moers’ work where she regards _Frankenstein_ as a “birth myth”? She posits this perspective in her essay “Female Gothic: The Monster’s Mother”. In it she argues Mary Shelly is working through her own feelings of anxiety regarding motherhood. Naturally this reading does not undermine the novel’s leitmotif of the dangers of scientific knowledge and shows how much range Shelly had as a writer and how many different ways this text can be read.

You expressed an idea of Romanticism in a way that I didn’t initially see but is correct: that some tendencies of Romanticism are developments from the Enlightenment thinking, particularly concepts of individualism and individual rights and an interest in naturalism. Nice job on your article!

I’d love to hear your thoughts on ‘Flowers for Algernon’ and ‘The Lawnmower Man’, as well as on Ursula Le Guin’s demand for science fiction authors to offer a positive vision of utopian possibility rather than obsess over the Dystopian – which is far more common as a trope in modern literature. Really good read. I want MORE!!

Great read!! I recently took a queer sci fi class in which the professor referred to Frankenstein as early queer sci fi because it is a male birth fantasy and because of the scene where the creature is on top of the hill wondering how he could be so alone in the world (a queer thought, indeed, and very relatable for us queers who grew up in a small town). I also love Philip K Dick & recently read Ubik (amazing!). Highly recommend it!

Extremely thorough and well written article! Love that you explored Byron’s pessimism as well