How YouTube Commodifies Experience

Media theorist Marshall McLuhan, in his 1967 book The Medium is the Massage, writes that “[e]lectric circuitry profoundly involves men with one another. Information pours upon us, instantaneously and continuously” (p. 63). 1 Rather prophetically, McLuhan predicted a kind of cultural takeover we have only now come to strongly appreciate. To say that we are “profoundly involved” with one another may even be something of an understatement.

With the medium of YouTube, the biggest digital video hosting website to date, we have gone beyond simple involvement; we now live through each other, extracting in our lived experiences commodities to be digitized and sold to wanting observers. Watching YouTube videos goes beyond a voyeuristic act and becomes an inherently participatory one. That is, the YouTube audience has become something of an “observer-participant”.

How Did We Get Here?

In 2005, Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, and Jawed Karim launched YouTube to a small subset of users. 14 years later, 2 billion monthly users visit the website, 2 and YouTube has become a household name synonymous with web video. Within 15 years, YouTube has become a juggernaut in the online video world, with its closest competitor being Vimeo (with 240 million monthly users). 3 In this time, YouTube has undergone multitude changes; from content creators to the website’s UI, the monetized, advertising-integrated, professional, sleek YouTube of 2020 is unrecognizable compared to its late 2000s/early 2010s counterpart. This shift can be noted from its different homepage layouts alone.

The earliest YouTube users will likely have a certain nostalgia for just how homemade the website and its contents felt. Granted, rose-tinted glasses help with this nostalgia, but with videos about lip-syncing, cats, and babies biting fingers, YouTube was a haven for (relatively) lower quality home videos and free entertainment. That early “YouTubers” such as Fred and Smosh would create web videos in their own homes contributed to this effect; these content creators often filmed videos on digital handheld compact cameras that struggled to hit a 720p video resolution. This is not to say that early YouTube was free from profit-making; Google had, of course, already purchased YouTube in 2006 and was exploring different avenues of advertising. Back then, however, the advertising was non-invasive, and would typically take the form of “semi-transparent banners” that would display on the lower half of videos. YouTube, without a tremendous amount of policy and regulation, was a breeding ground for content creators who could make entertaining videos for cheap. This led to the rise of popular YouTubers: Fred, Smosh (as mentioned above), CommunityChannel, IISuperwomanII, Nigahiga, and a myriad of other creators gained popularity using nothing more than a home camera and their personality.

As a sweeping generalization, the culture of YouTube has become more polished over time. In 2006, the most subscribed-to YouTube channel was a fictional series dressed as an authentic vlog – lonelygirl15 was a channel featuring a vlogger whose life appeared to become increasingly more bizarre, culminating in accusations of inauthenticity and eventually outing the series as a hoax. 4 Part of the allure and mystery was simply that the concept was novel; the vlog, being intertwined with authenticity, was primed to fool viewers and entrance them with what was then a new medium. Then, for a few years up until the turn of the decade, YouTube was dominated by sketch channels such as nigahiga, Fred, and Smosh. Vloggers and talents such as ShaneDawsonTV, MysteryGuitarMan and DaveDays (both of whom are musicians) were also gaining in popularity. RayWilliamJohnson, a series revolving around a personality (Ray William Johnson) who reacted to and compiled popular videos each week, was also becoming popular. 5 This era of YouTube can be characterized by its grassroots nature; content creators were never more than a few individuals, and sponsorships and advertising had not yet become so pervasive.

Then, as time went on, sketch videos became less popular, while vloggers, personalities, gaming channels, and reaction videos became more popular. By 2015, channels such as Smosh and nigahiga became larger production teams that produced high quality videos, competing with the more polished content of the time. Organizations were coming into the fore; machinima and TheFineBros were channels that acted as a collective. Channels such as PewDiePie, HolaSoyGerman and others were quickly becoming popular by playing games. These videos may be considered under the same umbrellas as reaction videos; after all, content creators were simply reacting to another piece of material – video games . Many content creators would vlog, too, and some channels were specifically for vlogging and storytelling, such as Jennamarbles. The technical quality of these vlogs were steadily becoming better. Where there were once laptop and handheld cameras, there were now DSLRs and well-lit rooms. Not only that, personalities were becoming better at presenting their “real self” on screen. It was a kind of manufactured authenticity. This describes the culture that has only gained prevalence in YouTube today. The rest of the article will attempt to tackle what this entails.

Though digital nomads and natives would be hard-pressed to find a specific instance during which YouTube truly changed to its current polished self, a few good markers of this shift would perhaps be as follows: YouTube Partners; the introduction of pre-roll ads; the introduction of music service “Vevo” that allows YouTube to distribute music legally; YouTube’s “Trueview” that allows ads to be skipped after 5 seconds; investments in celebrities to create content for YouTube; the introduction of YouTube Red (later renamed YouTube Premium), a paid service that removes ads from videos and allows access to paid content; the increased difficulty in getting videos monetized through harsher policies, creating a revenue slowdown. 7 All of these point to a trend in YouTube – and indeed, most other digital companies – that focuses on creating profit where there had previously been none. Features and changes in YouTube moderation are, for the most part, profit driven or simply to make the platform more sleek and efficient. A prime example is the star-rating system: noticing that most videos would either get 1 or 5 stars, YouTube forwent its stars for the more sleek and accessible Likes. 8

YouTube generated $14 billion through ad revenue in 2019. At our current juncture, the website is the farthest things from its roots. The largest YouTube channel at this time is an organization – T-series, a Bollywood music label. 9 This is a far cry from YouTube’s origins in slice-of-life home videos. Many of the aforementioned vlogs and “vloggers” have transformed from small teams or individuals with cameras into corporate businesses with production value on-par with TV shows. YouTube is no longer thought of as simply a platform for web videos; controversies and the colloquially termed “adpocalypse[s]” that challenge content creators’ ability to earn revenue construct a YouTube that is much more akin to any other giant tech organization. It is now impossible to overlook its close ties to its parent company, Alphabet (Google).

To Live Vicariously Through YouTube

Given the current polished state of YouTube that has long departed from sheer homemade, low quality, low fidelity videos, the content that appears on YouTube are now much more likely to be calculated, constructed pieces that aim to appeal to the human experience. In an NPR episode entitled “Close Enough: The Lure Of Living Through Others”, host Shankar Vedantam explores the enticing nature of YouTube videos:

“Irene suspects these women don’t actually live like this, but she doesn’t mind the artifice. She herself doesn’t have the bandwidth right now to make side dishes or exfoliate. She’d rather watch someone else do those things and, for a few minutes, escape into another person’s life. It’s cheaper. It’s simpler. And the emotional results – close enough.”

“Living vicariously makes us feel like we have the things we want even when we can’t have them. It’s a substitute for the real lives we lead and for the things we lack in those lives. Living through others also fills deeper needs. It can fill holes in our psychological lives and serve as a self-esteem pick-me-upper.”

“It almost feels like it’s filling a void that, you know, I haven’t been able to fill ever since, you know, in high school – that was the closest I ever came to being a musician.” 10

https://www.npr.org/transcripts/691697963

Watchers of YouTube videos have gone far beyond observers to being observer-participants. One could argue that in the late 2000s, YouTube was indeed simply about watching. Somewhere along the way, however, as video quality improved alongside a drive toward capturing attention for profit-incentives, the content started giving more to its users. Alongside food videos, 11 “unboxing” videos, 12 and other videos that center on a non-human subject, vlogs and vloggers have also become more closely authentic (and therefore involved). The ability for YouTube to capture emotional nuances through HD (high-definition) video invites a strongly participatory experience. This is somewhat paradoxical, given how non-authentic the production on YouTube has, as a whole, become.

This authenticity may be derived from a variety of ways. Researchers Silke Jandl argues that “the audiovisual medium allows for the illusion of a face-to-face conversation” (p. 182), that “fine facial movements caught by the close-up camera shot suggest authenticity” (p. 185), 14 and thus observers do not simply live vicariously through vloggers as they do other genres of YouTube videos; instead, watchers are likely to form a kind of intimate, emotional relationship – akin to a close friend. Andrew Tolson argues that the way YouTubers present themselves, interact with the audience, and lack expertise add to the construction of an authentic vlogger. 15 Thus, not only are YouTube users living vicariously through experiences recorded and put online, users also form pseudo-relationships with the content creators on screen. The medium of the web video is positioned in a way that creates this sense of authenticity.

Reaction Videos: To Watch Together

Reaction videos are an integral part of YouTube that draw observer-participants deeper into the ecology of YouTube, and into a closer relationship to the authentic vloggers they watch. Simply defined, reaction videos are watching people watching. A typical reaction video is comprised of primary material (video, text, games, or any other source piece that is being watched by the watcher) and the secondary watcher (the content creator, usually a vlogging personality that simply reacts to the primary material). On present-day YouTube, entire channels are devoted to reaction videos. BIGQUINT INDEED 16 reacts to rap songs, MackeyFam Reacts 17is a family that reacts to TV shows and movies, and TheFineBros’ REACT 18 reacts to everything from music to other YouTube channels. Each of these channels have millions of views; reaction videos have become their own genre on YouTube.

Reaction videos date back to 2007, when creators found an audience in watching the infamous “2 Girls 1 Cup” video. 20 The video itself is “a gross-out fetish porn clip”, and YouTube users could find a variety of groups and individuals reacting to it online. To watch “2 Girls 1 Cup” reaction videos is to watch the primary material through a proxy; “to experience its dangerous thrill without having to encounter it directly”. As YouTube became more and more popular, reaction videos no longer became simply about reacting to content that broke social norms. As evidenced by the aforementioned channels, reaction videos quickly became simply about seeing genuine emotion, and living vicariously through the emotions of someone else. People started reacting to other YouTubers, pop culture, comments, games, and anything under the sun. Reaction videos, like many other genres of videos, became a fresh source of content for content creators, and another means through which watchers could experience the world through a new lens.

Thus, to place the phenomenon of reaction videos in the web of the YouTube network, reaction videos allow observer-participants to be involved in relationships between creators. A subset of reaction videos are response videos, in which content creators respond to each other’s videos through the public platform. In these cases, users also become part of the relationship. When watchers are invited to see relationships unfold and further comment on them, they are invariably drawn into this social web as an individual with agency. When YouTubers sit down in front of a camera and react to something with genuine emotion or relay their thoughts about another creator, the relationship of the observer-participant is like that of a friend, listening in and being part of the process. The phenomenon of reaction videos rising in popularity, starting from “2 Girls 1 Cup” and ending with a whole genre, reflects an audience becoming more involved with the social nature of YouTube.

The Comment Section

The comment sections of YouTube videos are easily the most participatory aspect of YouTube as a whole. The comment section is the site on which the watcher gets to engage directly with the creator, as well as fellow watchers. The comment section, that has existed since YouTube’s conception, has always been the means through which creators can engage with the audience. Features of the comment section, such as “likes” and “replies”, allow discussion from a participating audience. Unlike the television or movie, discussions could be had right underneath the content being discussed.

Recently, YouTube added a feature to “Pin” comments, as well as “add hearts” to them. 21 This signals YouTube’s desire to actually incentivize participation. By creating means through which creators can directly interact with their audience, watchers are likely to become even further engaged and involved with the content they are watching. Often, creators will ask questions during the video itself, opening up the comment section to responses. They will then pick their favorites out with these tools, allowing watchers to have a stake in this close relationship between content creator and themselves.

The average YouTube observer-participant is then created on multiple levels. Firstly, to live vicariously through the (often mundane) things people do online is itself enticing. Watching people study, play music, eat good food, do the dishes – this can be not only a way of living through someone, but can also be “therapeutic” to watch. Living vicariously is not limited to skydiving, traveling, or any other high-adrenaline, inaccessible activities. It can be a way to fill up parts of our lives that we feel are missing, or simply be an escape.

On another level, the steadily improving quality of the YouTube image creates a picture that entrances us. The well-defined video allows capture of the slightest emotions, creating a “face-to-face” effect. On this level, the YouTube video surpasses the authentic and becomes intimate. Then, the observer-participant goes beyond living vicariously; indeed, the participation now becomes a kind of close relationship between content creator and watcher. It is no surprise now that controversial creators like Logan Paul, who posted “a video of him and friends discovering and filming a dead body”, still manage to maintain a group of loyal followers who likely feel emotionally bound to them. Logan Paul, as of today, has 22 million subscribers on YouTube. 22 The observer-participant is deeply involved and closely intimate.

Commodifying the YouTube Experience

YouTube’s intimate and participatory nature makes it a fertile ground for advertisers and advertising. For brands, there is little better in the realm of marketing than deep, organic connection with consumers. Thus, the age of the observer-participant is also marked by how these experiences have become poisoned through mass production. Experiences are intertwined with advertising and revenue, promoting consumption and creating media spectacles. For videos about food, an escape for many, Google marketing is deeply aware of their popularity. In 2019, “views of food and recipe content grew 59%, and social engagement (such as likes, comments and shares) on food channels rose by 118%”; “the heightened engagement of these audiences makes them especially valuable for brands”. 23 Food videos now transform from a simple piece of (sometimes instructional) entertainment into a vehicle for product placement, sponsorship, and similar promotions. The marriage between product and entertainment is perfect; oftentimes, food products can get eaten or cooked right on screen to glowing reviews and for a hungry audience. The simple, pleasurable, vicarious experience has been exploited and turned into one mined for profit.

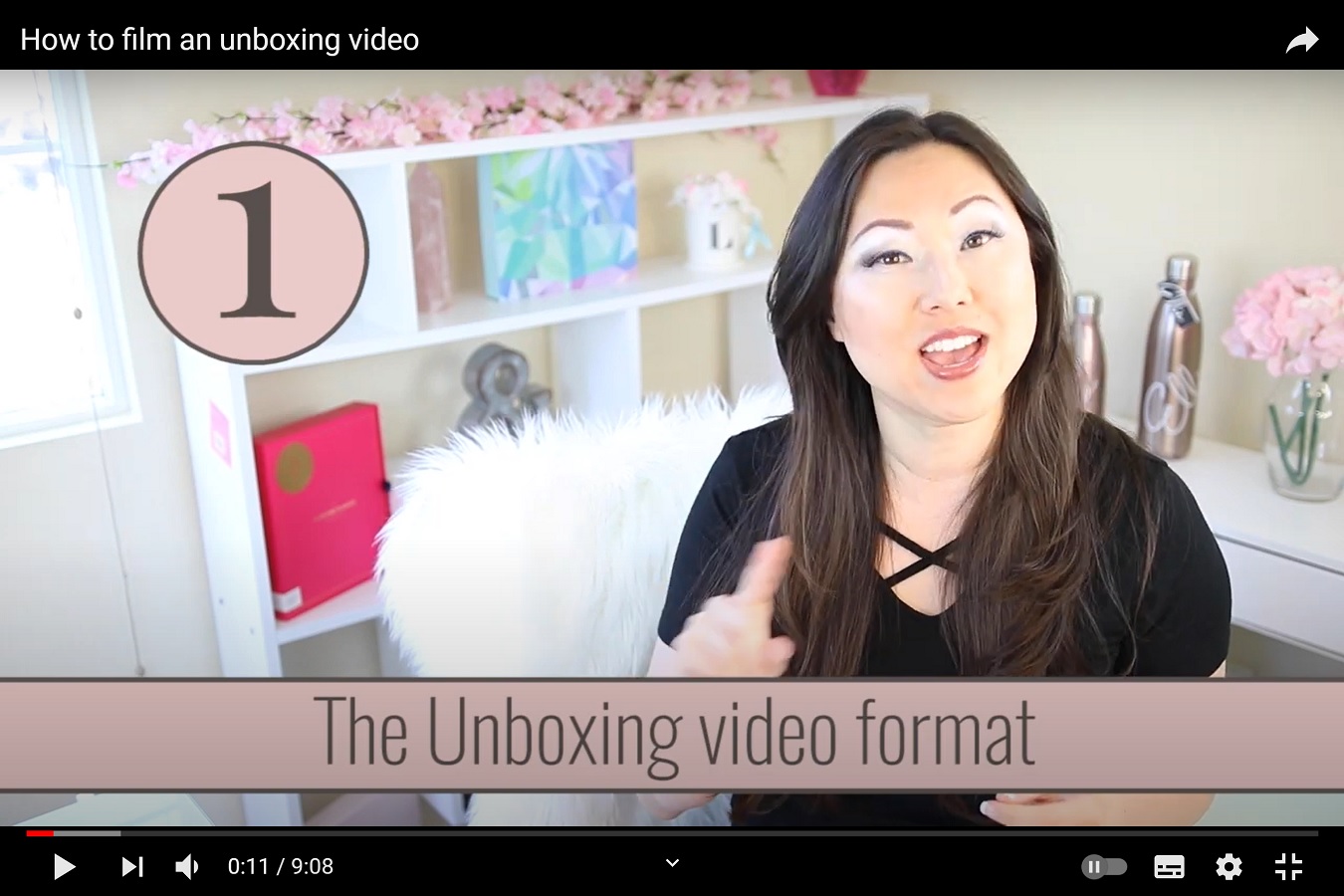

Similarly, unboxing videos – videos revolving around watching a content creator open a new (usually tech) product – are ripe for profit. “Over 90,000 people type ‘unboxing’ into YouTube every month. There are almost 40 videos with over 10 million views.” 25 “[I]t’s not just about the box. The product is wrapped in custom tissue paper. The box and tissue paper come together to create a memorable unboxing experience.” 26 The comfort of watching unboxing videos stems, in part, from experiencing the relish of being “surprised and delighted” without having to spend the money on our own packages. Yet, in the long-run, the popularity of these videos that exploit the engagement of the observer-participant serve to promote consumerist messages. The sheer number of unboxing videos is a somewhat dystopian reflection of consumer-culture – after all, how is buying goods and opening them entertainment enough? That brands focus on the boxes in which their products come may promote unnecessary wastage indicates that the very practice of unboxing videos may be innately environmentally harmful; this aside, blatant advertising still mars the innocuous nature and simple joy of watching. Forced to participate and engage, discount codes and product placement turn videos from entertainment to profit, and the viewer from observer to observer-participant.

For vloggers, product placement can be especially effective. The above mentioned intimacy between vlogger and observer-participant means that the consumer is much more likely to trust products pushed by vloggers. To recall the “close friend” relationship, an advertisement from a friend is likely to have more authority behind it than one from a stranger. This, however, is blocked by various rules and regulations governments enact that require full disclosure of advertising. 28 Oftentimes, web videos contain advertising disclosure from the vlogger – e.g. “this video is sponsored by [blank]”, “this was made possible by [blank]”. This style of disclosure is so popular that the brands behind them have become a kind of meme in themselves; for advertising to become a propagating meme is nothing short of a dream for profit-chasing advertisers. While these disclosures diminish the effectiveness of marketing, there is nonetheless a certain trust on the part of the observer-participant that their friend-YouTuber would not lead them astray, and would only promote quality products.

The next stage of commodification is in the genrefication of videos themselves. To be self-referential, through this article, the ability for me to refer to various types of videos – food, unboxing, fashion, vlogs, reaction – position these videos as being part of their own genre. A simply observing user would not have the sheer amount of choice that circulates today. YouTube itself, in allowing users to select videos out of a myriad of identical ones, forces participation out of its user-turned-consumers. Illustrated, this is the difference between the yard sale of early YouTube and the mass department store of YouTube today. The early YouTube user may stumble on something quality out of a small selection of goods, but the present YouTube user is faced with a mass of products of similar quality and has to make a personal choice.

Exploring the trend of queer YouTubers “coming out” on YouTube, scholars describe “coming out stories” as “media spectacles”. 30 When a certain kind of video becomes immensely popular, a thousand follow its style. Like Fordian mass production, the videos are nearly identical, and consumers must choose the ones they watch. Now, however, there is the possibility for each content creator to form a connection with the observer-participant, pushing products and creating what is essentially a contemporary brand loyalty. Pre-Internet companies could only dream of such consumer engagement. Further, genres of videos essentialize certain norms – for instance, the aforementioned scholars question the paradoxical promotion of heterosexual normativity by creating a spectacle of coming out stories. How true may this be of any other “trend” or genre on YouTube that might be inadvertently promoting harmful beliefs? This, however, is beyond the scope of this article.

The Observer-Participant

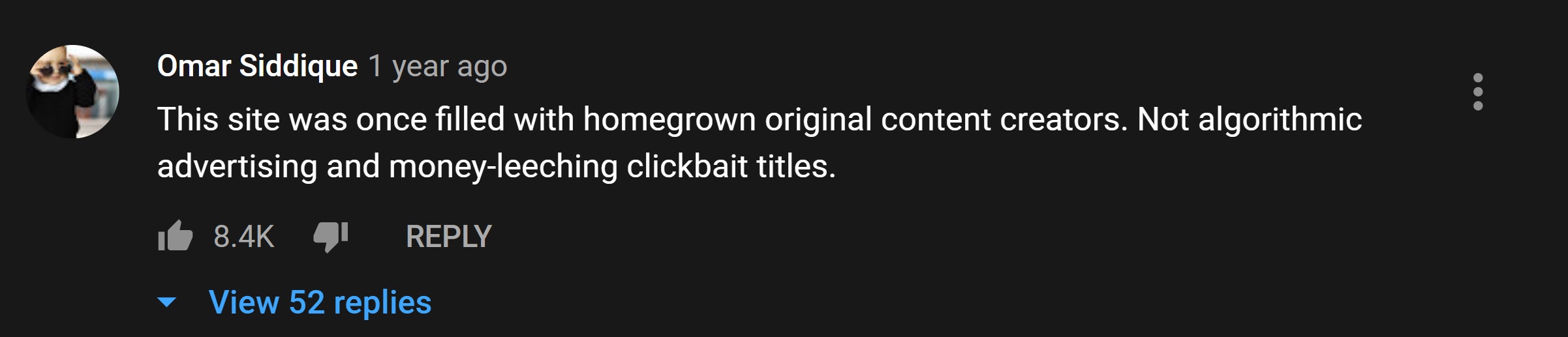

To say that we are only living as observers in this digitized age is deceptive. We are participating in more ways than one: users live vicariously through the content they consume, form relationships with the content creators they watch, actively choose the videos they want to see (out of a collection of identical ones), and interact with people behind the screen. It is to be expected that, from there, the participation is exploited for profit; that product placement is pushed on observer-participants should come as no surprise to anyone. The polished YouTube of today stands in stark contrast with the messy, homemade YouTube of the late 2000s. YouTube, since its conception, has been a platform for casual viewing and entertainment. The YouTube of the past is still here, albeit scrambled into a platform for profitable ends, with products that cater exactly to our needs as consumers.

The age of the observer-participant signals a group that enjoys watching; in doing so, they live vicariously through the things they see, and grow attached to the creators that create their content. Then, they inadvertently allow their in-depth involvement to be exploited for profit. The age of the observer-participant is the age of commodified, profitable experience. This, however, lends itself to the belief that observer-participants are doomed to head down a path of extreme experiential exploitation for the sake of profit. This is not the case. YouTube may appear to be a platform continually moving in one (profitable) direction onwards. It is, however, also a site of nostalgia and remembering.

Nostalgia: A Non-Linear History of YouTube

As much as this article has outlined YouTube’s changes over long periods of time, it is apt to end this article with a note that videos on the platform commonly endure. Like a self-archiving museum, much of the content that was once available on YouTube is still readily searchable on a multitude of different YouTube channels. Old videos, clips of old television shows, older music, and anything else nostalgic for an individual can remind us that technology is not inherently deterministic – it has a human quality that is determined by the humans who create it. As much as YouTube culture changes, and the digital era pulls users along for the ride (for profitable ends), the mass archive of content available on YouTube functions as a nostalgic reminder of what once was. Even now, one may find YouTube videos from the early 2010s appearing in their recommendations, and YouTube clips from dated television shows are incredibly popular.

It is entirely possible to go back to reminisce at old Smosh sketches, relive clips from 1990s pre-YouTube television shows, or find music from decades ago. One could argue that this is just another way YouTube sucks its consumers in: the tremendous amount of content acts as a means to keep users participating on the platform. While this is true, we may choose instead to find in nostalgia a resistance to the wave of entertainment commodification. As observer-participants, engaging in nostalgic content serves to remind us that this sleek, polished, constantly-adapting digital platform was not always the norm.

In what is now a platform brimming with sponsorships and paid promotion lies relics of a non-commodified user experience. If this was once the case, so can it be again – for the observer-participant, it is imperative to understand that participation does not necessarily entail exploitative profit, and that the once innocuous, grassroots, community-based world of YouTube is something to which we can strive. To cede support for advertising policies, to support content creators on other platforms or through other means (e.g. Patreon), and to be vocally critical about YouTube’s practices are all paths through which one can hope to return YouTube to its homemade (albeit messier) beginnings. If YouTube is nothing without its users – and it is – then observer-participants can choose not to participate.

Works Cited

- McLuhan, Marshall, et al. The Medium Is the Massage: an Inventory of Effects. Gingko Press, 2005. ↩

- https://www.businessinsider.com/history-of-youtube-in-photos-2015-10#late-2004-three-early-employees-of-e-payment-startup-paypal-chad-hurley-steve-chen-and-jawed-karim-start-working-on-an-idea-for-a-website-for-users-to-upload-video-dating-profiles-they-work-out-of-hurleys-garage-in-menlo-park-california-1 ↩

- https://www.juicer.io/blog/vimeo-vs-youtube-marketing-guide-for-video-content ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lonelygirl15 ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VmdEuVil4-g ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VJn-wvKmD5k ↩

- https://www.businessinsider.com/history-of-youtube-in-photos-2015-10 ↩

- https://techcrunch.com/2009/09/22/youtube-comes-to-a-5-star-realization-its-ratings-are-useless/ ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/user/tseries ↩

- https://www.npr.org/transcripts/691697963 ↩

- https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/marketing-strategies/video/millennials-eat-up-youtube-food-videos/ ↩

- https://www.commonsensemedia.org/youtube/what-are-youtube-unboxing-videos ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1PIoiV2dp1c ↩

- Jandl, Ingeborg, et al. Writing Emotions: Theoretical Concepts and Selected Case Studies in Literature. Transcript Verlag, 2017. ↩

- Andrew Tolson (2010) A new authenticity? Communicative practices on

YouTube, Critical Discourse Studies, 7:4, 277-289, DOI ↩ - https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCO_XmNLTsemq7Qn0yVQKfag ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQYn8JngNGOr5wHp53Oby5w ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/finebros/featured ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kpst9pKY438 ↩

- https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/27/magazine/reaction-videos.html?_r=1 ↩

- https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/6000964?co=GENIE.Platform%3DDesktop&hl=en ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG8rbF3g2AMX70yOd8vqIZg ↩

- https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/marketing-strategies/video/millennials-eat-up-youtube-food-videos/ ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XHmAM7gIIU ↩

- https://packhelp.com/unboxing-phenomenon-why-people-watch-unpacking-videos/ ↩

- https://packhelp.com/unboxing-phenomenon-why-people-watch-unpacking-videos/ ↩

- https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1536231-starter-packs ↩

- Arayess, Sarah, and Dominique Geer. “Social Media Advertising: How to Engage and Comply.” European Food and Feed Law Review, vol. 12, no. 6, 2017, pp. 529–531. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/90021214. Accessed 24 Dec. 2020. ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y0JDDx9U9jg ↩

- Ridder, Sander De, and Frederik Dhaenens. “Coming Out as Popular Media Practice: The Politics of Queer Youth Coming Out on YouTube.” DiGeSt. Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies, vol. 6, no. 2, 2019, pp. 43–60. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.11116/digest.6.2.3. Accessed 24 Dec. 2020. ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bnV4A6B6Otk ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Fz3zFqLc3E ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The real problem is that you can’t search for anything without shuffling through endless conspiracy videos.

YouTube is useful. I’ve watched political debates, DIY videos, how to fix videos. You name it.

The problem is the teenage demographic and the predatory nature of YouTube. If you want views and money, you’re targeting that demographic.

You’ll do that through click bait, juvenile humour and/or just being attractive. Vloggers will occasionally do the most outrageous thing to out do others and stop their channel stagnating. It’s the perfect formula for YouTube ‘stardom.’

The problem is that YouTube has allowed this to happen. You demonetise anything that isn’t child friendly and thus you lobotomise creativity, interesting, inspirational, instructional content, in favour of “DAY #1878: OMG MY SISTER DID THIS please subscribe.”

It’s a monster of YouTube’s own creation.

Youtube is good for the more obscure non mainstream music lots of people upload records from the 60’s. 70’s 80’s etc and no adverts.

Also can be good for more specialist interests, some decent documentaries….

But it is also full of people being stupid and (mainly ‘right’ wing’) political crap that always tends to infest my youtube feed. All it seems to take is watching part of one of these political moticated videos and they quickly start popping up on your feed. Jeremy Kyle also gets on my feed but that I have to accept the responsibility for that!

Another notable things is the rampant use of sexualised images in the cover / preview photo to draw people to watch videos.

If you want to make money on Youtube, you make a video with an extreme opinion, with an angry clickbait title, with content that is easily digested within a minute. That same formula is used throughout the internet because it works.

It also leads to more extremity and polarisation.

I don’t know what the answer to this is, but the issue isn’t the platform, its the internet itself.

Youtube is great if you know who to sub to. Less than 1% is good but the trick is avoiding the rest of it.

Youtube may be full of all sorts of crap, but it’s also a wondrous treasure trove of videos and of music that you grew up with (or before), of musicians, of teaching, and some fantastic political analysis by the likes of The Young Turks, Sam Seder, The Real News and The Jimmy Dore show. Amazing insights into what’s really going on, compared to the frankly awful and transparent propaganda on the mainstream media.

My favorite political commentators on Youtube are Michael Brooks and Jeff Waldorf, neither of which would have a chance of a career on a mainstream TV news outlet. Thanks to Youtube and Patreon they’ve been able to develop their own styles (radical Marxist academic and adorkable, respectively), find their audiences and flourish.

I just checked out Michael Brooks, and immediately recognised him, yes,he’s a really well informed, astute and calm speaker. Also he’s associated with Sam Seder, which is why I saw him coming up in my feed and watched him before.

The real threat is advertising and how sites must bow down to censorship based on the ad’s they want to run and revenue they need to collect.

The citizens of the world made youtube what it is today.

The future for YouTube is either shit loads more adverts or a pay wall, that seems to be the route Google are taking, which is fundamentally different from what YouTube was supposed to be, Corporations 1 – Public 0.

YouTube is amazing, but not because of YouTube. It’s because of the content on YouTube. Navigating YouTube these days is clunky and ridiculous; it’s impossible to find out what the top viewed videos of the past month are for example, and searching for a specific video is near-impossible. Furthermore, the comments sytem remains inherently broken. If a better video platform comes along I could easily see YouTube going the way of Bebo and MySpace.

Something that I recall is an interesting topic re: YouTube is the rise of livestreams/podcasts, and the chat and superchat features therein.

This is a bit like reading a few books you don’t want to read in the library and subsequently declaring that public libraries are useless.

Good comparison. But you are missing the point of this great article.

Youtube is yesterdays news. All the cool kids stream on twitch nowadays.

I remember trying out youtube when I was 11 years old in 2005 (when it was born and released), I’ve actually grown up with it now after 13 to 14 years now, I’m 24 years old now since that time. YouTube went from the wild west of videos to Incorporated videos where even cable channel networks and many other brands started to creep up on YouTube- despite all of its flaws, I still love YouTube and a huge fan of it, I’ve learned a lot from it, gained a lot of fun experience from it too and on the bad side I’ve seen some racist people on there, while I’ve seen too many times where YouTube have failed to back against neo-nazis and many other forms bad stuff that has crept on there. Again YouTube is a massive beast, right up there with Facebook and honestly, I can’t any other video social network compete with that (in terms of vlogs, games, comedy and documentary videos) provided by YouTube 24/7 (365 days) per year.

Youtube is the reflection of us the users, newspapers are a reflection of the owners and their ideology. One is certainly more democratic.

YouTube just need to keep in mind that content is the thing, and it’s not all about the ads.

Right. The ads have gotten worse and worse. These days, you can’t watch a 10-minute clip without seeing at least two ads. They also have the terrible habit of interrupting videos right in the middle of a scene or sentence.

These internet monopolies like Facebook, Youtube, Ebay, etc will be challenged. Mainly because every generation needs its own identity and where they used to find it in music or fashion it will become part of a cultural expression.

I love Youtube. Its great for following artists (sketching/painting kind) that I like (and finding new ones), and for all the advice/instruction that they offer for free. I also like it for reliving my musical youth.

I just wish the UI was better…it really can be a pain in the posterior.

The best, and worst, part of YouTube is the comments. The comment universe on YouTube is truly horrifying, even the most innocent video will get the most horrible, rock your faith in humanity, comments. Sure, that’s the story of the Internet in general but YouTube just makes it so accessible. You don’t need to search for it like you do on Twitter, it’s there, right in your face.

Pewdiepie had his own come apart over the comments, but he’s not the only one (just the biggest). If I had a YouTube channel, and thank god I have a real job and don’t have to go down that path, but, if I did, then I would make it clear that comments are monitored and moderated. Then I would employ someone, or find an unpaid intern or something, to delete unpleasant comments.

I don’t understand why the big names don’t do this already.

*Then I would employ someone, or find an unpaid intern or something, to delete unpleasant comments.*

That sounds like the kind of dream role anyone would do for no money whatsoever.

The problem is YouTube is not doing enough to discourage certain behaviour. In fact, instead of banning certain users from their platform they’re rewarding them with ad revenue.

Come on now. Where else can you watch The Streets performing Fit But You Know It, live on Jonathon Ross in 2004? Answer me that.

Youtube is now so big that you can find virtually anything you want. If you want to find stuff that demonstrates how bad it is, then you will find it. Although the reality is that what people search for is a reflection on them and nothing more.

I used to use YouTube all the time, mostly to find old shows I grew up on (nostalgia game strong). Then I started discovering criticisms and commentary I liked, so I stayed for that. These days though, my feed is cluttered up with stupid ads, conspiracy videos, “fake” videos (labeled as something completely different from what it actually is). It’s frustrating to say the least.

I think what has made YouTube entertainers so popular is that the platform is so inherently personal. Viewers get a very intimate glimpse into the personal lives of the people they admire. With a quick comment they can interact with their favourites too. When compared to passively watching film and T.V., for example, this is as close as fans can get.

This is probably why live-streaming is now surpassing YouTube, because it is even more interactive and personal.

If any social media platform should come in for criticism it should be Twitter. The others actually can have a useful function.

When are people going to learn? NONE of these companies care about anything other than profit margins and pleasing their Wall Street masters. Period.

There’s some really good stuff on you tube if you want to learn to play an instrument, repair a watch, replace a washing machine part, strip down and rebuild a car engine, learn to use a sewing machine, see how to make a good homemade style vegetable biriani etc. The list goes on and on. All good stuff. If you’re a teenager wanting to learn the guitar for example, it’s a absolute goldmine of demos, tutorials etc. and indeed still is if you are an old git who likes to play for fun and wants to learn something new. I am sure there’s a load of terrible stuff as well, but you have to try not to be distracted by that.

It’s like any tool -the results are entirely dependent on how you wield it.

If you only go looking on YouTube for the prurient and infantile then that’s all you’ll find. I’ve availed myself of everything from guitar tutorials to economics, psychology and physics lectures, from how to smoke a pork shoulder to how to repair the heater on a 2004 Ford Fiesta. It is a remarkable resource.

Youtube is uncool and will die out soon if doesn’t change the design and introusivnes of the ads. Haven’t watched anything on it for months. It looks like a scum site currently… Awful.

Youtube is still the best place to find obscure music.

I remember when YouTube wasn’t owned by Google.

You should check out ‘Bug’ a show that Adam Buxton was doing, I am not sure if he still does it.

The whole show is based around the absurdity of YouTube comments. He is really funny and has an impressive beard.

There’s some great educational vids on YouTube… it’s like humanity as a whole, mostly sh*t but with some nice bits at the edges.

I prefer to think it’s mostly good/nice/informative/entertaining with some shit bits at the edges which seem to garner a lot of attention.

Classical music videos/audio and ASMR videos make YouTube worth it for me.

Unfortunately, I think YouTube and its culture of commodified experience will not change until Youtubers are granted sources of income that A) pay a living wage, and B) do not overly rely on 3rd party sponsors. A big thing that shifted YouTube’s average video was the monetization of videos over 10 minutes long. Although a video may warrant quality content for 3-4 minutes, creators seek to stretch their video to the lovely 10 minute mark for more advertisers, despite the ‘true’ quantity of material within the video. While some may argue this leads to more content within a video–more time to watch their favorite Youtuber–this effect, in my opinion, sacrifices video quality for video length. Remember a time when gaming channels seldom produced a video longer than 7 minutes? Now you’re hard-pressed to find any gameplay video shorter than 10, the minimum requirement for more significant monetization.

If YouTube wishes to churn more quality videos, they should adjust their monetization algorithm to be based on views, with some adjusting factor that considers the ratio of upvotes to downvotes. Through this, experience–while remaining a commodity–is presented as ‘good’, quality experience, rather than ‘experience’ itself.

YouTube allows users to upload, view, rate, share, add to playlists, report, comment on videos, and subscribe to other users. Available content includes video clips, TV show clips, music videos, short and documentary films, audio recordings, movie trailers, live streams, video blogging, short original videos, and educational videos. Most content is generated and uploaded by individuals, but media corporations including CBS, the BBC, Vevo, and Hulu offer some of their material via YouTube as part of the YouTube partnership program.

I think sooner or later there will be a massive shift away from YouTube in favour of other video platforming sites. Already apps like TikTok have largely captured the attention of a new generation due to its addicting algorithm. It will be interesting to see how Youtube changes in the next decade or so.

This article aptly articulates the problem with modern Youtube: how a growing portion of content on the site is oriented towards profit instead of self expression. I used to browse the website every day, but now I only visit it on occasion and spend an hour at most watching videos. These days I spend most of my time watching old films and reading literature.

well I would say youtube is the best platform for quality video production people

This was a nice overview on the history of YouTube usage, functionality, and overall content. I appreciate this as a writing topic, as though it’s a major platform these days, I rarely see its topic inspire articles. It’s also baffling to see how quickly YouTube has changed in its relatively short lifespan.

YouTube has become a megalithic platform and in a sense content has become commodity and cheapened. Other media such as Vimeo are setting targets and segmenting the audience market. It is inevitable that YouTube will be going the same way. Another interesting phenomenon is audio books on YouTube. Image is helping but not the primary communication.

This was a thorough summary of the history of use, the features and the entire content of YouTube.It is also puzzling to see just how fast YouTube has changed over a very short period of time. I like this as a subject for writing, as I seldom see its theme inspiring posts these days as if it was a big forum.

Youtube is highly addicting. There really should be disclaimers before every video, or maybe before signing up for account, that specifically outlines the mental health consequences Youtube binge-watching can have on an individual. There needs to be more concrete research done on this subject so people can band together and promote this feature. Hopefully then the Youtube audience will decrease and the emphasis on ad revenue will diminish as well.

I remember hearing this quote from a YouTube video I was watching once. The video begins with asking the question if people still watch YouTube. Of course as explained there are the vlogger or streamer types of YouTube’s but there are more audio centric creators out there. I myself am entrenched in the audio focused creators such as podcasts or video essays. It’s interesting that this progression is occurring in today’s youtube

Thanks for such an insightful article.

Great job on this article I believe an addendum is in order.

This is an excellent article. The argument of the observer-participant becomes increasingly true in the digitized world. I think the same could be said of sports- it’s no longer simply about watching sports or playing sports: there’s fantasy sports, following players and stats, watch-parties, etc etc. I think the rise of multi-media subcultures plays a big part in the immersion and participation aspects of “observing.”

A good essay, perceptive.