The Mandalorian’s Response to the Western Genre

Star Wars has always been synonymous with the sci-fi and space opera genres. But from the opening scenes of the Tatooine desert to the gunslinger standoffs depicted in The Book of Boba Fett, Star Wars resembles a classic Hollywood Western. Audiences in 1977 who saw Luke Skywalker return to the tragic scene of his home destroyed by fire, his beloved family burned to death, need only have cast their eyes back 20 years to find the same scene in The Searchers—arguably the most famous film to come out of the Western genre. Standing aghast as fire destroys his brother’s home and family, John Wayne begins his own journey much as Luke does in A New Hope.

But the recent Star Wars adaptation of The Mandalorian takes this Western influence and turns it on its head. While still looking like a Western, The Mandalorian subverts key themes of the Western genre and challenges some of its problematic elements: the racist othering of Native Americans and the hypermasculine individuality of the cowboy. Clad in the literal and metaphoric armor of the cowboy, the Mandalorian nevertheless inhabits the roles of the “Other” and the “Father Figure.”

What is a Western?

The American Film Institute defines a “Western” as a film “set in the American West that embodies the spirit, the struggle, and the demise of the new frontier.” Westerns frequently take place after the American Civil War, in the latter half of the 19th century, using desert terrains, sweeping landscapes, ranches, small frontier towns, and saloons as their backdrops. Thematically, Westerns revolve around nostalgia for the “conquest of the wilderness and the subordination of nature, in the name of civilization, or the confiscation of the territorial rights” of Native Americans. Western plots can usually be boiled down to the fight between good and evil, often manifesting in the struggle between white settlers and Native Americans, who are portrayed as uncivilized savages deserving of conquest.

The Cowboy is the face of the American Western. Stereotypically a white male, the cowboy is the undomesticated, honorable individual who embodies the American dream of “manifest destiny”–the idea that colonial settlers of the United States are entitled to explore and govern the American West. Cowboys could even be seen as the American descendants of the chivalrous knights of Medieval English folklore, much like the Jedi in Star Wars. The cowboy is often a skilled sharpshooter or gunslinger who enforces justice, appearing as either the hand of law enforcement or a vigilante. He arrives in the nick of time to protect frontier towns, settling disputes or repelling attacks by Native Americans tribes. The cowboy tends to be a nomad, his heroism deriving from his role as the lone soldier–a model of 19th century American masculinity, ruggedness, and individualism.

Exemplifying these characteristics, John Ford’s 1956 film, The Searchers, is the quintessential Western. Set on a ranch in the romantic landscape of the Western frontier, a family’s home is burned to the ground by a Native American tribe of warriors known as the Comanche. Ethan, played by John Wayne, sets out on a mission of revenge and to rescue his niece, Debbie (Natalie Wood), from the Comanche’s clutches.

Wayne’s Ethan personified the glorified vision of the American cowboy. John Wayne was the All-American Man of the fifties, an actor synonymous with rugged masculinity and a vociferous opponent of Communism. Audiences at the time likely projected this impression onto Wayne’s Ethan, who was designed to represent everything that a classic American cowboy was thought to be: a white individual who refuses to be tied down and seeks to cleanse the frontier of murderous brutes. As a morally complicated man who didn’t “believe in surrenders,” Ethan was the great anti-hero of the American West.

In the latter half of the 20th century, Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) shed much of the idealistic glamor of the Western, yet it retained and refined many of the threads sewn by Wayne and Ford in The Searchers. Though Unforgiven is considered by many to be a Revisionist Western because of its cynical and ugly vision of the cowboy lifestyle, the film upholds the traditional barriers between cowboys and family life. The cowboys in the film frequent a brothel, fornicating with sex workers who take center stage in the film’s plot. These cowboys thereby reject monogamy and marriage. Although their mistreatment of women contradicts the chivalrous origins of the cowboy, Unforgiven reveals the sinister side of the same coin–cowboys are hypermasculine and domineering.

Eastwood himself picked up the mantle from Wayne, embodying a similar notion of masculinity through gritty performances that called his character’s morals into question. In Unforgiven, he plays William Munny, a former assassin notable for his brutality and murder of innocents, yet he is ultimately the harbinger of justice for a group of female sex workers after law enforcement fails to condemn their abuser. While we meet him as a father who no longer considers himself a cowboy, he soon abandons his children and returns to his old, murderous ways. Eastwood thereby preserves Wayne’s legacy of the cowboy as noble, fierce, and undomesticated.

The Mandalorian as The Cowboy

The Mandalorian utilizes several features of the Western: space travelers exploring the outer rim of the galaxy, impressive landscapes, gunfights in bars and small towns, and ultimately pitting the forces of good and evil against each other.

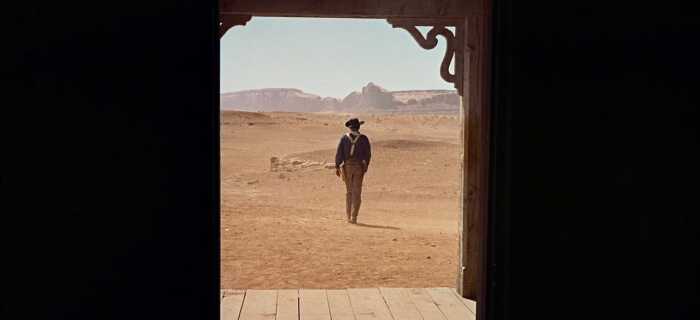

To cement its Western status, The Mandalorian begins by recycling an iconic scene from the conclusion of the Searchers. In one of the most influential shots in cinema history, Ethan stands in the doorway after returning Debbie home. Instead of entering the house to join his family, Ethan lingers at the threshold before turning away from the camera to return to where he truly belongs—out in the wild west. The door slams shut.

The Mandalorian picks up where The Searchers left off by replicating this shot to introduce its protagonsit, Din Djarin (Pedro Pascal), known simply as Mando. The door slides open to present Mando in the doorway with the treacherous frontier in the background. Mando flashes onto the scene, gun in hand, as the cowboy back from the desert for his next mission.

Like the cowboys of the Western genre, Mando stands for justice, proceeding to break up a barfight. But Mando then captures the victim of the brawl, who turns out to be the target of his latest mission. Mando is a gunslinging bounty hunter but also a protector. He mirrors Ethan’s image of the lonesome, nomadic anti-hero, as well as Will Munny’s noble hired gun with a complex moral compass.

Mando’s development as the show progresses highlights similarities he shares with Ethan. Just as Ethan sets out to rescue Debbie, Mando seeks to rescue The Child, Grogu, and return him to wherever he may belong. Though Grogu begins as just another bounty, Mando gradually forms a bond with Grogu, one that forces Mando to change his individualistic, bounty hunter lifestyle, and ultimately leads him to contravene his religious code. Like Mando, Ethan must also overcome his instincts and moral code to rescue Debbie. Upon locating the Comanche camp, Ethan discovers that Debbie has accepted the ways of the tribe, donning Native American dress. Despite his hatred for the Comanche and his desire to avenge the deaths of his family members, he ultimately chooses to save Debbie, embracing her as he once did when she was a child.

At first glance, then, Mando is the classic cowboy of the Western genre. But The Mandalorian subjects its cowboy protagonist to two transformative role-reversals. By “othering” Mando and casting him as a father figure, The Mandalorian undermines the 20th century Hollywood perception of the cowboy, replacing him with a revamped cowboy who addresses 21st century concerns about racism and gender stereotypes.

The Mandalorian as The Other

At its core, the conflict between the cowboy and the Native American stems from a racist depiction of Native Americans as subhuman. Worse still, they are portrayed as simply another dangerous element of the Western frontier that the white cowboy must conquer to fulfill his manifest destiny. In The Searchers, for example, the Comanche are shown killing innocent civilians and removing the scalps of their dead enemies.

The racist caricature of Native Americans in Western films functions as a method of “othering,” a concept that casts people who do not meet the social standards of Western civilization–and in the case of Native Americans, people standing in the way of colonial expansion–as alien. Filmmakers in the Western genre regularly deploy this tool to clarify the distinction between the film’s protagonist, the cowboy, and the film’s antagonist, the Native American.

The Searchers places this racial boundary at the center of its narrative. Ethan is disturbed by Debbie’s adoption of Comanche garb and ritual. He is torn between saving her and leaving her behind because she has joined the enemy. At the film’s climax, Ethan catches and lifts Debbie, unclear whether he intends to save or kill her. Though he chooses the former, the suspense preceding this moment derives from Ethan’s racist hatred for the Comanche tribe.

Mando, on the other hand, mirrors Debbie in that he is a “foundling.” He was discovered by a group of Mandalorians as a child, raised as one of their own, and now follows in their ways while wearing traditional Mandalorian armor.

While Mando may look and act the part of the cowboy, his devotion to his creed more closely resembles the deeply rooted culture of Native Americans in the Western genre. Mando belongs to a religious sect of Mandalorians, observing ancient customs and performing traditional rituals. He follows a strict set of rules that forbid him from removing his helmet. His actions are dictated by a Mandalorian code, habitually invoked by the motto: “This is the way.” Mando is teased by the group of fellow Mandalorians he meets in Season 2 Episode 3, led by Bo-Katan Kryze (Katee Sackhoff), who dismisses him as “one of them”—part of a religious sect who broke off from mainstream Mandalorian culture.

Mando is thereby “othered” in similar fashion to how Native Americans have historically been othered in the Western genre. At once a lone soldier and dedicated to his tribe; an individualistic bounty hunter subservient to a culture and cause much greater than himself, Mando is the cowboy reimagined.

The Mandalorian as The Father Figure

The heroic cowboy, similarly to the Jedi, relinquishes his family attachments in favor of the quest for manifest destiny. He belongs on the frontier, not in the safety and comfort of the family home. He is a masculine specimen who must not be tied down.

In The Searchers, Ethan makes this choice twice. The film implies from the outset that Ethan loves his brother’s wife, but never pursued a relationship with her because he chose the cowboy lifestyle instead. Ethan relives this decision in the “Doorway Scene.” Pausing at the threshold, he contemplates joining his remaining family inside. Instead, he turns his back on the warmth of home and family, understanding that his place is on the frontier. The film slams the door in the face of his longing, perpetuating the hyper-individualistic, undomesticated symbol of the cowboy.

Unforgiven concretizes this stark division between the lives of the cowboy and the family man. Will Munny has hung up his cowboy boots to marry his wife and have children, explaining that upon meeting his wife, he gave up drinking and killing to become a “fella like anyone else.” In other words, he is no longer a cowboy because these two lifestyles cannot coexist.

When approached to bring an abusive man to justice, he initially refuses, standing inside his home while his children can be seen in the background. But, in need of money after his wife’s death, Will accepts the assignment, abandoning his children and consequently revisiting his violent cowboy past. The change does not take root, however, until he learns of the death of his partner, Ned (Morgan Freeman); Will begins swilling whiskey as we hear the awful extent of his past sins. By the end of the film, Will has lost his work wife and their accomplice, The Kid (Jaimz Woolvett), who leaves because he does not want to become like Will. Having lost both his literal and figurative families, Will transitions from the father we met chasing after his pigs in the mud with his children to a depraved cowboy who murders those who stand in his way.

The Mandalorian toys with the anti-family trope of the Western genre by hypothesizing what would happen if the cowboy could juggle his lifestyle with that of a father figure. Throughout The Mandalorian, Mando can be seen tending to Grogu as any ordinary father would their child. He protects him, he feeds him, he sends him to school (S2E4), and he even imitates a father playing catch with his son when Grogu plays with a small metal ball on Mando’s ship (S1E3, S2E6). Gradually, Mando and Grogu develop an attachment as Mando transforms from the lone cowboy to the father figure that Grogu needs.

Similarly to Ethan at the end of the Searchers, the Season 2 Finale sees Mando having to part ways with his newfound son, Grogu. But by displaying Mando as a father figure, this goodbye is all the more difficult to watch because it carries emotional heft. Mando is a father losing his child, whereas Ethan’s departure befits his primary role as the cowboy.

When the door slams shut behind Ethan at the end of The Searchers, the film implies that his mission has been accomplished and he has accepted his role as the cowboy. He is giving up any hopes he harbored of being a family man. Mando, on the other hand, reunites with Grogu in The Book of Boba Fett. Faced with a similar choice to Ethan, Grogu must decide whether to continue his training with Luke and abandon his ties to Mando or to return to his adopted father. Grogu picks the latter. Mando may have thought that his mission, like Ethan’s, was complete when Grogu departed through the doorway with Luke. But Grogu’s decision to reunite with Mando demonstrates the enduring father-son bond that the pair have fostered.

To underline Mando’s fatherhood, The Mandalorian leans on the recurring theme of paternity and family in Star Wars, recycling imagery from earlier Star Wars media. The original Star Wars trilogy rested on one of the all-time great plot twists revealed in Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back: Darth Vader is Luke’s father. Episode VI: Return of the Jedi illustrates how Luke, now a more seasoned Jedi, reckons with the aftermath of this discovery. Moving on from his initial anguish, Luke believes he can find the good that remains hidden deep within his father. The movie concludes with Darth Vader sacrificing himself to rescue Luke and defeat the Emperor (for now, at least). As he nears death, Vader requests that Luke remove his mask so he can look upon his son with his own eyes.

The conclusion of The Mandalorian Season 2 sees Luke return to take Grogu as his new student. Grogu is reluctant to leave Mando behind, much as Luke expressed to Vader that he would not leave him on the imploding Death Star. Mando then removes his helmet, violating the rules of his creed so that Grogu may see his adopted father’s face, and echoing the removal of Vader’s mask in Return of the Jedi. By evoking this heartfelt scene, The Mandalorian places Mando in the suit of Star Wars’ most famous father figure.

By converting its hero from a classic cowboy to a father figure, The Mandalorian reinvents the Western genre. It teaches a lesson in coopting the themes and imagery from pillars of the genre and inverting them to craft a refreshing reincarnation of the cowboy. The Book of Boba Fett has already followed this example by giving audiences an intimate look into the rich culture of the Tusken Raiders, previously degraded with the moniker of “Sand People.” Star Wars, much like other recent refurbishments in The Harder They Fall, The Power of the Dog, and Nope, is redefining a genre in urgent need of an update.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I’ve never been the biggest star wars fan, but I think you did an exceptional job with this one.

I love the deep dive into the franchise’s Western roots. It’s interesting to see project-by-project which of George’s initial influences for the OT get leaned into more.

It’s the most explicit version of a Western Star Wars.

Timothy Olyphant must love playing Sheriffs as much as Sam Rockwell likes playing Racists and Elizabeth Debecki playing a Damsel in distress.

He was the Marshall of this place, the Sheriff of Deadwood and a Deputy US Marshall in Justified.

So maybe it’s the starry badges. Although his role in the Mandalorian seemed self-appointed.

Pedantry aside, he was, as always (note never watched Hitman) ace

And John Krasinski chins.

It’s rehashing a lot of tropes from Western/action TV serials of the 80s, 70s, 60s & 50s. But you know what? Hardly anyone under the age of 35 has watched any of those shows.

I’m 36. I find this pretty uninspired. I can almost hear the committee talking about putting Boba Fett in a western.

Hes a bounty hunter. On a planet largely covered with sand and moss eisly is like any spit and sawdust boozer from a plethora of westerns. What do you epect?

Yes its a western AND its bloody great fun, whats so wrong with that!

Jon Favreau should’ve been put in charge of the sequel trilogy, he clearly understands the franchise better than anyone else at Disney

Actually it’s both him and Dave Filoni that deserve both credit.

There is no sequel trilogy, it doesn’t exist!

Mando series is a pure and simple Western. None the worse for that but, speeders and ships and all those common-or-garden Lucas types in every inevitable dusty saloon apart, it’s every Western you ever saw.

My wife got Disney+ and I must say the only thing I’ve watched is The Mandalorian. I really enjoyed the first series but I think it was because it had that Saturday afternoon action vibe of the A-Team or Knight Rider that I used to watch as a kid and felt like a real throwback. I never really felt it was “Star Wars” though. But then if it wasn’t I (and many others) probably wouldn’t have watched it. Will certainly watch Series 2 though.

Star Wars was always a Western in space. Lucas forgot that for the prequels. I love the Mandalorian for being an unashamed Saturday matinee programme. Quick, easy, rewatchable stories full of action and fun.

The Mandalorian is not even that great. Disney threw lot of money at it, like the dumb Star Wars sequel trilogy, with its bells and whistles but this is just stupid fan fiction. Star Wars is George Lucas and the day they stopped following his vision, for better or worse, it is now just a bunch of logos and lightsaber toys and baby freakin’ kid Yoda’s. They will just keep churning out this trash ad infinitum. People think this is good because everything since the original trilogy has been rubbish. That is the measure of the Mandalorian’s “quality”. It is just made it sell silly Yoda toys and “expand” the universe so they can make even more toys. Wash and repeat mofo’s, wash an’ repeat. Hollywood got lots of cash to make silly Star Wars TV shows yet they never made the Gandhi movie sequels. Go figure.

There are plenty of traditional Star Wars fans who saw through the ruse. Many think The Mandalorian is fine as an Expanded Universe story, but that’s it. The damage by Disney has been done, hence the relative failure of Solo, The Rise of Skywalker and The Galaxy’s Edge theme park attraction and the bargain bins full of Star Wars collectibles.

Money is staying in pockets and Disney/Lucasfilm are starting to worry about it.

The day they stopped following Lucas’s vision was the day Star Wars was saved.

The franchise owes its success to Maria Lucas.

Such a great show.

When I first watched it after all the trailers had hit, I was a bit taken aback to find that, really, this is a kids show.

Stuck with it and glad that I did.

I’m not a massive star wars fan but I prefer this to the films. It’s takes itself less seriously and is just good old fashioned entertainment at the end of the day.

Hopefully new Star Wars projects incorporate more Western influences, and go back to the franchise’s roots

Once they’ve stopped stop mining the most creative Star Wars minds like Joe Johnston and Ralph McQuarrie it really has very little to offer.

And? It’s family entertainment, aimed at kids above a certain age.

THIS IS THE WAY! 😉

Action. Humour. Special effects. A bit of cuteness.

It’s back to basics Star Wars.

And I f*cking love it.

Not a bad show. All the depth of a puddle but it’s Star Wars so just enjoy it for the utter guff it is and was always meant to be.

I found the 1st series a bit dull tbh. The episode of the week format reminded me of Lost in Space and even though Werner Herzog was heavily trailed he was barely in it.

Loved it and as someone who grew up with Star Wars, this was absolutely everything i wanted to see from this show and more.

So, if it was everything you wanted to see, it was nothing like the Disney sequels?

I loved the sequels, this is a different animal, better than the sequels, many orders of magnitude better than the prequels. On par with the original 3

It’s Lone Wolf and Cub (Babycart) in Space, but I’m fine with that.

Agreed. I’m sure that it’s not a coincidence and, again, I’m fine with that, too.

It certainly wouldn’t be the first time that Lucasfilm had drawn inspiration from a Chanbara classic.

The Manalorian Rocks. I have spoken.

No, you have written. And misspelt.

I know I’m in the minority but think season 1 was incredibly overrated. The plot, what little of it there is, moves at an incredibly glacial pace, each small event is tediously stretched out to fill an entire episode. Nothing of any significance happens in the show, its purely fan service and if it didn’t have the Star Wars costumes nobody would rate or watch it.

The entire plot of the first season was mando finds the child and agrees to take him back to his people.

There is nothing to be had from this show except some nice callbacks and fan service to the original trilogy.

Just gets everything right that the sequels got wrong.

I found it a bit plodding and old-fashioned. Maybe that’s the idea. A lot of the time it felt like watching a 70s/80s “mission of the week” TV show, the kind of thing Glen A Larson or Stephen J Cannell would have put out. At other times I felt like I was watching a contemporary single player video game: here’s the cutscene establishing the current objective, now go do the mission, okay, great, you did it, here’s a new piece of Beskar armour and 500 XP. On to the next mission.

A fair comment, but very much part of its charm.

Very interesting article! You’ve explained the parallels between westerns and mando so well

The Mandalorian is excellent, although Disney is in serious danger of overcooking the Star Wars franchise in general.

I have watched a lot of Star Wars and I’ll probably watch a lot more, but when it comes down to it I can’t help feeling that the only Star Wars that is any good is the original film. The rest of it is fun, sure, some more than others, but none of it captures the menace of Vader or the innocence of Skywalker like the original. It became of cliche of itself and it has got worse as the franchise goes on.

Empire Strikes Back and Rogue One would like to have a word with you.

I really enjoyed it. Surely this is what Star Wars should be about.

The Mandalorian is popular because of new characters, some fan service and hints to filling some gaps in our knowledge.

I do like The Mandalorian, but it feels as if we may already be on the path to some serious Star Wars burnout.

I appreciated this article for its Western film canon compare and contrast approach to give insight into the greater frames of reference in the character development and symbolism of Mando and Grogu. I’ve often had these conversations with my friends around its Western framing but not dug particularly deep into all the specifics of how it was done. I wondered if a mention of Mando’s almost romance and setting into the community of the Krill farmers with a ready made family might have been a good example of Mando turning away from domesticity. But otherwise I enjoyed the comprehensive review of the examples against established film tropes:)

That’s a great thought about Mando turning away from family! I think this ties in very well because the episode occurs early in the show (Chapter 4 I believe), so Mando is still a typical cowboy at this stage. It takes time for him to learn what it means to be a father and have some shape of a family. On that note, The Mandalorian also has something interesting to say about how families viewed as unconventional, e.g., single parents, are families all the same with the same strong bonds.

oh yeah, that is so true! I forgot about the single mum reference there with the Krill farmers, thanks for mentioning that:)

It did looked like a bit of western while watching the mandalorian.

I enjoyed this article and the deep dive into the Western genre. As a long time fan of all things Star Wars – (I was in middle school when “A New Hope” hit the theatres, so that tells you something of my age) I have found the Mandalorian to be a great addition to the Star Wars universe. The “space western” format provides a unique way to tell Mando’s story. His gradual transformation from a hired killer to devoted father is endearing and Pedro Pascal’s voice work is perfect in my opinion. I believe the appeal of of Mando for so many fans is his vulnerability that comes from being a father. The lone cowboy is no longer alone, yet he is still a hired gun, which does indeed turn the idea of the old school cowboy on its head. The episode with the Marshall, played brilliantly by Timothy Olyphant reinforce that Western trope and provides a bit of humour along the way.

I remember watching the first episode of Mando and seeing him walk into that bar like in an old western movie. I knew right then that I would enjoy the series because it wore so heavily the western genre on its list of influences. Great article!

This is an amazing article! I always thought that the Mandalorian simply adopted Western echoes to help make it relevant and relateable. Your article, however, openned my eyes to the real nuance of Mando’s character–both in his adherance to the cowboy trope, and his departure from it. This combination of the two is what makes him such an entrancing character–but I did not realize this until reading your article! I also never realized there were so many reflections of Western films and other Star Wars films in the Mandalorian’s cinematography. Thank you for making these connections!