Percy Shelley and Charles Bukowski’s Whirlpool of Decadence

Percy Shelley and Charles Bukowski are famous for their polemic poetry describing the immorality of people. It is not a secret that everything that lives soon finds death. Yet, we call death in his language of decadence and immorality.

Ozymandias

When scholars discuss Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias, the big focus is on Ozymandias’s pride and the punishment that results after that. Of course, death is inevitable. What we don’t expect is the systems and organizations that we, as humans, have built to be brushed by death. King Ramses II Ancient Egypt collapsed which he thought would remain powerful forever. Charles Bukowski thinks similarly in his poem, Dinosauria, We. In which he predicts what will happen to us in our society. He predicts that our society will crumble and fall apart. It is something that is inevitable yet, we do not expect it. This essay focuses on the similarities between the poems and how their themes connect.

In Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias, the poet describes the pharaoh as a ruler that commandeered with a “cold command” What we have is the lasting legacy of how Ozymandias was perceived. He was perceived as a tyrannical ruler. Despite the collapse of the pharaoh’s kingdom, the perception of him captured on his statue remains. That is the lasting legacy that he wished for. Shelley states, “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone stand in the desart…” (Shelley 790). The author indicates that only fractures of his “works” remain. It is ironic how the sculptor’s work of art remains but the rest of his kingdom, the people, the markets, the buildings, the bureaucratic systems, never lasted compared to the artistic rendering of Ozymandias. Nothing is permanent, but art is eternal.

So, why does Shelley have this negative view on Ozymandias? It is a look at how oppressive rulers harm their civilizations more than benefit them. The way in which Shelley describes Ozymandias is pessimistic. He is described as an excessively prideful tyrannical ruler with a sneer of cold command. Shelley appears to blame Ozymandias for his kingdom’s downfall. One could say that nature destroyed ancient Egyptian society, but nature here is secondary to Ozymandias’s actions. Nature is the clean-up crew that reclaims everything that was once built, consumes it, and returns it to its original form. Shelley introduces Ozymandias by his statue which is a crafted project by human hands. The statue is a symbol for the Egyptian King’s kingdom and its man-made buildings that signal human achievement and prowess. Obviously the statue is also Ozymandias because it is a “mocked” image of him. (Shelley 791). Therefore, because Shelley presents the audience with the pitiful desolate chunks of rock that once were Ozymandias, he signals that ancient Egyptian society no longer is because of some reason. Following the image of the broken statue is a description of Ozymandias’s character based on his visage.

Beigi explains that “Ozymandias presents an apocalyptic vision of the end of the history in its description of the arrogant and egoistic visage of the broken statue of Ramses II. (76). Shelley immediately gives an answer to the downfall of ancient society. He appears to attribute the downfall of ancient Egypt to the breath and the way that Ozymandias ruled. In Shelley’s rendition of the pharaoh, Ozymandias’s manner of ruling must have been astringent if the sculptor had to carve it into the statue’s sculpted face.

Ozymandias’s ancient Egypt may not have survived but the statue’s inscription at the base remains preserved. Shelley emphasizes the artistic interpretation of Ozymandias by focusing on the artist that mocked the face of the king[1] (791). What the traveller and, by consequence, what Shelley knows comes from the artistic encapsulation of Ozymandias’s character on stone.

It is the art that seems to outlast humans and human achievements. Shelley states, “Tell that its sculptor well those passions read. Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, the hand that mocked them, and the hand that fed.” The author indicates the sculptor’s artistic endeavor survived longer than Ozymandias. It could be a part of his romantic poetic identity that saw a connection between nature and art. Maybe, art, being a spawn of nature, lasts much longer in life than any other human fellowship. Maybe Shelley read Wordsworth at some point. Conjecturing the scholarly career of Shelley would serve for nothing but it is worth mentioning that art’s connectedness with nature is a grand motif of Romanticism in which Shelley is associated with.

If Shelley understood that art survives longer and civilizations survive less, what does that mean when he is writing Ozymandias? Shelley I suppose attributed the downfall of a civilization to a tyrannical king. The way in which the poem unfolds itself, it presents Ozymandias as a domineering and cold tyrant. It implies that the downfall of ancient Egypt is because of unfit rulers. Beigi states, “the poem represents the Romantic imagination that rebels against long-established reason,” (79). Shelley’s loathe for monarchy is a key element in understanding more about Oyzmandias. Shelley, in The Masque of Anarchy, is much more politically excited to denounce the corrupt and injustice of the English monarchy. It was as the poet states (43-44):

And if then the tyrants dare

Let them ride among you there,

Slash, and stab, and maim, and hew, –

What they like, that let them do.

‘With folded arms and steady eyes,

And little fear, and less surprise,

Look upon them as they slay

Till their rage has died away.

Here, Shelley suggests his audience of commoners to resist the attacks on them whether legal blows or physical abuses. Shelley suggests non-violent resistance which was brave of him to do but, after considering the Peterloo massacre, would have made the poet angry at another example of political upheaval caused by the hands of the “rich” (29). And this would not be such a far stretch of an idea because it was during the time of Shelley writing the poem that the French Revolution ended not too long ago. The idea of a monarchy as large and great as the French’s being torn down must be a source for the imaginative Shelley. King Louis XVI was an unfit tyrannical ruler with too much avarice that could burst his belly in two. France is a short distance away from England. That closeness makes the idea of change and the idea of egalitarian society much more tangible. Beigi quotes Edmund Burke in paraphrasing that the French, “had completely pulled down to the ground their monarch, their church, their nobility, their law,…their arts, and their manufacturers” (76).

It is sensible to believe that Shelley witnessed the French Revolution with a more subjective view. Observing the French Revolution as a possibility until then was unprecedented in scope and could have given the young poet the hope of improving conditions within his own country. After all, the political landscape of his own country was less favorable in his eyes. “Shelley’s discontent with the present moment, that is, his own time during the reign of George III…he shows a great desire for the glory of the past and a new Golden Age in the future” (Beigi, 79).

Shelley believed that all humans existed as part of a larger collective that unified. It was Shelley’s belief that tyranny was not only oppressive but also the catalyst for the decadence of a society. From Shelley’s On Life, he extrapolates his ideas of oppression and the important unity of humankind that seems to have disintegrated. In “Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Romantic Organicism,” Stefan Esposito quotes Shelley from On Life. “Let it not be supposed that this doctrine conducts to the monstrous presumption, that I, the person who now write and think, am that one mind. I am but a portion of it” (Esposito, 33). Shelley’s source for Ozymandias is the monarchal systems from French, England, and Ancient Egypt, and his Romantic beliefs of constructing an egalitarian method of living. Shelley sees from the collapsing kingdoms of Ramses II and King Louis VXI a budding flower that grows from that destruction. And that flower, For Ramses II in ancient Egypt is returning the desserts back to the way they were, untouched by human hands.

Dinosauria, We

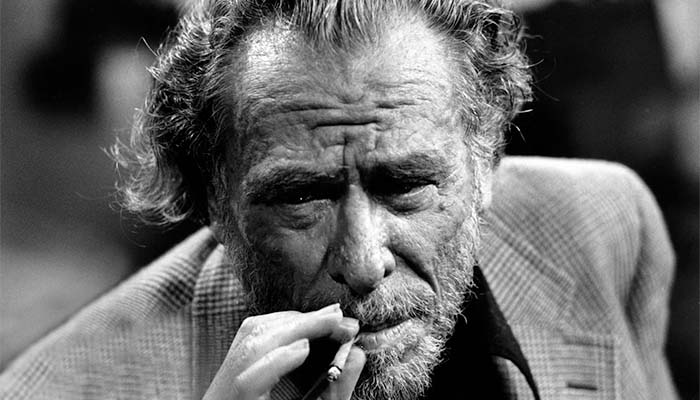

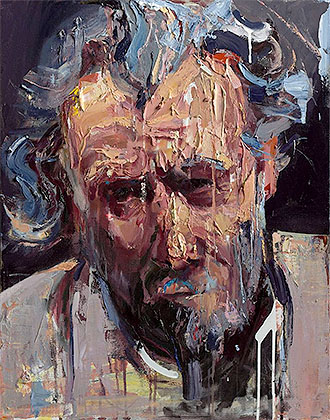

Charles Bukowski’s poem, Dinosauria, We (1991) is about the descent of humanity. The poem centers around similar themes as Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias as it observes the decay of civilization although Bukowski’s poem is different because it is not a retrospective look at an ancient civilization but a foresight of the future. Bukowski observes the economic decay and societal distress of his current world. He states (319):

Born into this

Into hospitals which are so expensive that it’s cheaper to die

Into lawyers who charge so much it’s cheaper to plead guilty

Into a country where the jails are full and the madhouses closed

Into a place where the masses elevate fools into heroes

Bukowski demonstrates what he has witnessed and continues to witness into the present. Hospitals, Law firms, penitentiaries, are all owned by the rich owning class. The biggest problem that these institutions have is their overwhelming desire for money. The avarice that influences these listed institutions is what is causing this economic downfall. Bukowski, here, is insinuating that there is a lack of access to services like medical care, judicial support, and to an extent, a lack of support from public servants. Given the extensive abuse to Americans, Bukowski could be foreseeing a revolution in the future or near future. The poem acts as a window into the future for the proletariat class as to what our collective future will be. For Shelley, Ozymandias is a hopeful rekindling between humans and nature. One day, the pillars of society as Shelley knew it will fall and a new one will rise. But for Bukowski, Dinosauria, We is a call to action because there will be no tomorrow. Unlike Shelley, Bukowski sees no prospect on the horizon but a cliff.

Madigan traces these attitudes of Bukowski’s disdain for society in works like Hollywood, where the author expresses, “his ambivalence with respect to the filmmaking process [which] counterpoints his ambivalence with respect to fame, wealth, and public acceptance” (452). An ambivalence that only grows more bitter with age. In Pulp, Bukowski depicts his attitudes with the Hollywood as an ascent and descent into “creative sterility” (452).

Hollywood is the poet’s taste of an industry that simulates the bureaucratic power dynamics of the governmental systems that have failed the United States. The producers–the ones with the money and power to influence a film’s production—have control over what happens despite any artistic pleads. Madigan, in his analysis of Bukowski’s Hollywood, paraphrases, “Jon Pinchot threatens to cut off his fingers with a chainsaw if his demands are not met by the producers, who try to dominate the creative spirit of the project through financial measures” (453).

The power structure here, depends on whom has the biggest wallet. For the actors, writers, cinematographers, and sound engineers, it is an unfair system to have one’s work thwarted by someone that most likely does not understand one’s job nor cares to know. For sure, Bukowski, having his novels adapted into movies was a reality that he knew existed but didn’t want to be a part of. In an interview with Loren Means, she asked, “I get the impression you’d rather have a bad job than a job connected with the art world.” He replied, “You’ve got the right idea, because, if you get into that, it can suck you up. If you’re too close to creation you can lose it all. You’re better off mopping the women’s latrine. It keep you straight.” (Calonne 262). Bukowski was not only talking about the creative world from an artist’s perspective. He understood from working in Hollywood that there exists a corrupt system in which profits are prioritized over the art. It surely rubbed Bukowski the wrong way.

Bukowski was often compared to the Beat poets of his time, but he did not align himself with the Beat movement at all. In fact, he thought of them as distracted by success rather than preoccupied with their work. Bukowski commented, “The Beats somehow make me sad. It’s like they just didn’t come through. They hung together too much…And they went for the media, the limelight. They slacked off on their work, their creation. Fame mattered more than just doing it” (Brewer 9).

Within the scene of poetry, Bukowski felt that even his contemporaries were more concerned with fame than creating art. Having observed the Beats and worked in Hollywood, Bukowski’s attitudes with staying in the proletariat class solidified enough to offer a perspective lost to those around him. Shelley and Bukowski both share sympathy for the working class and have fantasized their tyrannical, profiteering societies’ collapse.

Earlier in the poem, Bukowski indicates, “born like this, into this… as the political landscapes dissolve, as the supermarket bag boy holds a college degree,” (1991). Whether it is a lack of jobs or that college degrees are worth little, either way, Bukowski is implying that the United States is experiencing a societal decadence. So like Shelley, Bukowski implicitly attributes the problems that the United States experiences to the owning class.

Why might Bukowski have this negative depiction of the owning class? He has lived in the quintessence of capitalism. During his time living in Los Angeles, he must have seen many changes politically, socially, economically. Given that Dinosauria, We was written in 1992, three years before his death, it is reasonable to assume that Bukowski had experienced a lot of changes in Los Angeles since he arrived up until his death. The downward perception gave him a pessimism of the world thus translated into the poem. Another factor is that he was poor for the majority of his life. He stated that he did not make much money from his written works but once he did, it was enough to get by. His poverty indicates his negative attitude towards the owning class. It is no wonder that he shares sympathy for laborers. “Men march to work with dull faces and lunch pails, and Bukowski, despite his artistic concerns, often places himself among them. Such an inclusion both palliates and legitimizes what is often perceived as a misanthropic vein in the poet’s work” (Brewer, 98). Bukowski is an important figure because when we look at his poem Dinosaria, We, there are connecting themes like that in Ozymandias, I think it is special to see these links. One of the overarching themes that takes place in the poem is the fall of civilaztion. Civilization in both poems comes to a downfall but the key difference is that in Bukowski’s poem, he has the foresight to see that the world is ending as opposed to Shelley that saw the fall of a civilization falling.

Nature plays a part in the ending of civilizations. For Shelley, nature reclaims the civilization back, it consumes and makes returns it to nature. When reading Bukowski, the same idea of nature reclaiming civilization is present except it is nastier. Bukowski states (320):

The sun will not be seen and it will always be night

Trees will die

All vegetation will die

Radiated men will eat the flesh of radiated men

The sea will be poisoned

The lakes and rivers will vanish

Rain will be the new gold

Bukowski illustrates the effects of the United States’s problems. It only gets worse and worse until there is absolutely nothing redeemable left for any inhabitant of earth. The most interesting component is displaying nature as dying. Compared to Shelley, Bukowski’s poem has no savior. Nature reclaims Ancient Egypt and will eventually make it new again. But for Bukowski, what can reclaim, what can save the earth if the trees are also eradicated because of human vice. Again, the difference between Shelley and Bukowski is that Shelley has the hindsight to understand the repetitive nature of civilizations being erected and being brought down. Bukowkski on the other hand, must have that same hindsight, but understands the downward trajectory of world civilization due to more control, more disparity, and more powerful weapons. The poem might present an end that has finally arrived but it is a new beginning.

Of course, at the end of Shelley’s poem he states in reference to Ozymandias’s statue:

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

The ending mirrors Bukowski’s sentiment of nature consuming the discarded monuments of human achievement and leaves what was once previously there; nothing. Bukowski has the most dullest silver lining in which he says (321):

And the space platforms will be destroyed by attrition

The petering out of supplies

The natural theory of general decay

And there will be the most beautiful silence never heard

Born out of that

The sun still hidden there

Awaiting the next chapter.

Bukowski alludes that in the end, there will be a continuation. The sun, which will always be here, the ultimate dominator of life, dictates when life on earth will truly stop. It is a romantic idea that Bukowski maintains that nature is the true ruler of the world. It also highlights the same dilemma that Shelley wrote about in Ozymandias. The two poets present the same cycle of and the same hierarchy in our world that has existed for so long that it is part of nature. The desire and amassing of power is an issue existing for centuries and will probably exist for centuries to come. These cycles of nature, like a whirlpool, appear go round and round. The two poets imply that it is human nature to want more. The struggle between humans having and not having has existed for so long that it is inherently human. The most depressing part might be Bukowski’s insinuation that to break the whirlpool of power and subjugation, humans in our entirety must be gone so the earth can heal itself. Only then, can nature reclaim what it has lost as a victim to human greed.

Works Cited

Bukowski, Charles. “The Last Night of the Earth Poems.” Harper Collins Publishers, 2002.

Bukowski, Charles. Mathematics of the Breath and the Way: On Writers and Writing. Canongate Books LTD, 2018.

Brewer, Gay. Charles Bukowski. Twayne Publishers, 1997.

Greenblatt, Norton Anthology of English Literature Volume D, Shelley Ozymandias. W.W. Norton Publishing Company, 2018.

Esposito, Stefan. Communicating Life: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Romantic Organicism.

Michael Henry Scrivener. Radical Shelley: The Philosophical Anarchism and Utopian Thought of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Princeton University Press, 2014. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=791404&site=eds-live.

Jacqueline Mulhallen. Percy Bysshe Shelley: Poet and Revolutionary. Pluto Press, 2015. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1076161&site=eds-live.

Madigan, Andrew J. “What Fame Is: Bukowski’s Exploration of Self.” Journal of American Studies, vol. 30, no. 3, 1996, pp. 447–61. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27556179. Accessed 18 Oct. 2022.

Furnell, Gary. “Charles Bukowski and The Habit of Art.” Quadrant, vol. 56, no. 9, 2012. Ebscohost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsaed&an=rmitplus721085596460431&site=eds-live.

DUFFY, Cian. “‘Time Is Flying’: Lyrical and Historical Time in the Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley.” Gaziantep University Journal of Social Sciences, vol. 18, Oct. 2019, pp. 37– 49. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.21547/jss.602615.

Datli Beigi, Roohollah, et al. “Urban Decay or the Uncanny Return of Dionysus: An Analysis of the Ruins in Shelley’s ‘Ozymandias.’” Critical Survey, vol. 34, no. 1, Spring 2022, pp. 74–86. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.3167/cs.2021.340106.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe. The Masque of Anarchy. Woodstock Books, 1990.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

What a lovely article. If people are interested, you can hear Charles read the poem himself here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hRc6mHS9PjE

And how about Ozymandias read by Bryan Cranston:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sum6A2enC6s

Bukowski had the ability to create a character that is so arrogant and annoying but, at the same time, self-aware and self-loathing.

Poems like “the man with the beautiful eyes,” and “Dinosauria, we” are all classics and prove that Bukowski was indeed one of the great poets of our time! I have never read Ozymandias. I am reading that next. Thank you!

He is at his best when describing the atmosphere and quiet dignity of bars and cafés and other non-descript rooms.

Ozymandias reminds me how temporary this life is and how we’ll take nothing with us when we die.

Our vanity won’t leave us anywhere.

My favourite Percy Bysshe Shelley poem. Powerful and timeless reminder of the value of humility.

The Masque of Anarchy is an even more powerful poem. Definitely ahead of his time with the anarchist ideas.

I have always loved this poem – especially since I have spent so much time in Egypt, at Luxor. I will – and have – read this poem many, many times throughout my entire lifetime. It resonates within my soul, as I realize not just that all is transitory. “Look upon my works, ye Mighty, and despair.”

It holds a lot of symbolic and imagery content.

“Dinosauria, we” is possibly my favorite of Bukowski’s. It is uncharacteristically apocalyptic, a grand narrative of mankind’s self-destruction quite unlike the booze-soaked slices of life he was best known for.

My favorites are:

•destroying beauty

•to the whore that took my poems

•a poem is a city

•john dillinger and le chasseur maudit

•the genius of the crowd

I love: john dillinger and le chasseur maudit

Charles Bukowski knows how to title his poems. E.g. ‘Play the Piano Drunk Like a Percussion Instrument Until the Fingers Begin to Bleed a Bit’.

Can’t forget classics like ‘i wanted to overthrow the government but all i brought down was somebody’s wife.’

Oh boy. Bukowski is a sick oldie who hates women, and the edgy undercover incels love him.

Hear, hear. But in the moments when I don’t find his style performative, I find that his gruff, matter-of-factly cynicism and melancholic run-on sentences are surprisingly honest within his pessimistic self-depreciating worldview.

Ack… the awe-inspiring Dinosauria, We.

It is one of the most powerful poetry I have ever read.

Charles was brutal, gross, dark and humorous all the same. I never quite know what to expect from him and sometimes he writes lines that are so simple but hit so hard.

“and the hard words

I ever feared to

say

can now be said:

I love you”

And just like that, in just a few simple words, Bukowski strikes me down.

Everything in his poems just feels so… Normal… Like, all the bad nights and all the hangovers and all the empty bottles and all the anonymous humans you hook up with and the death and the years and the music and puking and dancing and all the small things that he constantly revisits in his poetry feels so natural and so alive and it feels like a life worth living and now I have to stop because I am writing literally without stopping *gasps for air*.

God, I hate that he was so fucking good.

Shelley is a great poet and I really really enjoy his poems. However, “Ozymandias” is rather different than others. I believe poems are about feelings. You feel close to certain ones and this is why some people feel personal connection to poems. “Ozymandias” is my poem and I absolutely love it.

It’s no secret that I can’t stand poetry, but I do have a couple of poems that I love, and Ozymandias is one of them.

Such a complicated individual.

Damn it, Bukowski. Why did you go off and die on us when we need you the most in days like these?

He is so much better than most the academic trash being published today.

So to conclude this article, power has a limit, has a period and nothing is immortal.

Very elegant, Monroe!

It’s amazing how Ozymandias resonates just as well nowadays as it did back in 1818, and how beautiful the poem is.

Only thing I didn’t like is when he refers to Ramesse II as ‘King of Kings’. Found that a bit blasphemist.

One line is enough to send chills down your spine.

The line, “look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!”, Is literally some of the best irony I’ve ever heard. The subtle mockery is both hilarious and incredible writing.

I also love that line. It’s a fun one to slip into casual conversation whether it belongs there or not.

Ozymandias is one of those poems that seems to continue to crop up. I first encountered it in high school during one of my English classes when we were looking at (surprise, surprise) poetry. It seems that whenever the topic of poetry comes up in high school, this is one of the poems that is looked at, maybe because it is short, but maybe because despite its shortness, it actually does have quite a lot to say.

With “Dinosauria, we”, it made you think about life, it’s beginning and ending, and made you reflect on who you are. Great piece of work.

Bukowski is able to convey meaning and feeling in a very effective way.

A lot of the poems of Bukowski doesn’t work for me – however, I find the conversational, autobiographical style quite interesting.

It’s really nice article, i really enjoyed reading this.

If there is one thing to be said about Bukowski, it’s that no one writes like him.

Dinosauria, We is prophetic.

Ozymandias is on the list of my all time favorite reads. It symbolizes political power but the statue is a metaphor for the pride of the whole of the mankind.

Bukowski doesn’t leave much to the imagination while Percy Shelley can sometimes be the opposite.

Bukowski sticks to reality and delivers crazy wild lines like nobody’s business.

“Dust, thou art to dust returnest” proves to be true at the end.

Your article does a great job of showing how Bukowski pushes the themes present in Shelley’s “Ozymandias” to their utmost, far past the limits of the extreme. What happens to “Ozymandias” when there exists no potential visitors to the remains of the long-dead pharaoh’s kingdom? Where then does the narrative point of view shift to? Bukowski asserts the only foreseeable option would be the Sun, aloof and indifferent to humanity as W.H. Auden concurs with in “The More Loving One.” Both poems seem quite different from William Shakespeare’s sonnets, such as “Sonnet 55,” about the arts’ attempts at immortality. There is still some traceable insecurity and uncertainty in those poems but, nonetheless, a defiant hopefulness as well.

Interesting read!. I always felt that Shelly’s poem is directed against all tyrants and dictators who think they will outlast time. The poem reminds them that time will tell that everything will turn to rubbles over time, and time is thus the real leveller.

I love reading articles like these that show connections in themes between authors of the past and the present. The ideas that vanity is toxic, material riches are ephemeral, and the written word will live on, are espoused, and have been espoused, since forever. But I would have never made the connection between Percy and Bukowski had this article not pointed it out.

I appreciate you! Very nice comment!

I love how this article does comparative studies so nonchalantly. Thank you for this pertinent comparison and the idea of Bukowski as similar to Shelly will already incite some debate, which is much needed.