To the Lighthouse and Virginia Woolf’s Rebellion against the Traditional Novel

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf is a representative work of modernism that made its appearance in the early decades of the 20th century. As a literary movement, modernism is characterised by its rejection of prior literary traditions, through innovations in forms and contents. Modernist authors radically shifted their attention from external events to human psychology through the method of stream of consciousness; they discarded chronological development by building plotless narratives; and they experimented with language forms. To the Lighthouse embraces all these modernist hallmarks and thus represents a complete breakaway from traditional conventions of the novel genre. As a matter of fact, Woolf even called it not a novel but an “elegy,” consciously distancing herself from established genre rules. Nevertheless, her rebellion was not against the high ideals of literature; instead, Woolf intended that her new form better serve the aims of exploring the meaning of human existence, which, in her opinion, was the sole purpose of literature and which the conventional novel form could not accommodate. To this end, she created, in To the Lighthouse, a uniquely shaped structure which transformed the traditional novel form.

A Novel with a Distinctive Shape

Woolf sculptured her novel into a tripartite shape of – in her own words – “two blocks joined by a corridor” (Dick 11), referring to Part I “The Window” and Part III “The Lighthouse,” connected by Part II “Time Passes.” While “The Window” makes up sixty percent of the novel’s length, and “The Lighthouse” thirty, “Time Passes” comprises a mere ten percent. However, in terms of narrative time, “The Window” occupies one night, and “The Lighthouse” one day, whereas the central corridor “telescopes the longest period of time (ten years) into the briefest chapter of the text” (Ellman 100). This design departs drastically from the conventional linear plotline and conception of time, but it serves Woolf’s symbolism perfectly. On the one hand, the two masses joined by a narrow passage mirror the final shape of the completed painting of Lily Briscoe (Bradshaw xlii), the central character of Part III through whose perspective the story is largely told; on the other hand, it presents an abstract visualisation of the island where the Ramsay house is and the island of the lighthouse, connected by the water passage. The shape is a symbolic image of the journey and transformation of the human soul through life’s perils – the novel’s main theme.

The novel’s structural design, which condenses time to a single night or day and space to a single place, also means that its narrative cannot extend along a timeline or expand to other locations as in traditional novels, but must instead develop in depth inwardly, building temporal and spatial dimensions within the inner consciousness of the characters. Lily’s painting technique of “tunnelling her way into the picture, into the past” (Woolf 142) describes also perfectly Woolf’s own technique in this novel. One example can be found in from Part III, where Lily, while painting on the lawn, tunnelled into the remembrance of a past scene of Mrs Ramsay knitting, deep in her own troubled thoughts, and forcibly interrupted by Mr Ramsay. “He stretched out his hand and raised her from her chair” (162). But the action of “raising her” immediately opens up another space into the further past to a scene in which a youthful Mr Ramsay reached out his hand to help the future Mrs Ramsay out of a boat, a decisive moment that led to their marriage. It is through such layered tunnelling that multiple temporal and spatial dimensions are created to fully enhance the characters, their interwoven relationships and complex impressions.

This tunnelling technique is used so broadly in the novel as a whole that time is stretched almost limitlessly to accommodate multiple inner worlds of the characters. For instance, the first six chapters of “The Window” seem to be one elaborate scene around a single conversation about the possibility of going to the lighthouse which might be reconstructed thus:

Mrs Ramsay: Yes, of course, if it’s fine tomorrow. But you’ll have to be up with the lark. (7)

Mr Ramsay: But it won’t be fine. (7)

Mrs Ramsay: But it may be fine––I expect it will be fine. (8)

Tansley: It [the wind] is due west. (8)

Mrs Ramsay: Nonsense. (9)

Tansley: There will be no landing at the lighthouse tomorrow. (10)

Tansley: No going to the lighthouse, James. (16)

Mrs Ramsay: Perhaps you will wake up and find the sun shining and the birds singing. (16)

Mrs Ramsay: Perhaps it will be fine tomorrow. (16)

Mrs Ramsay: And even if it isn’t fine tomorrow, it will be another day. (24)

Mr Ramsay: There wasn’t the slightest chance that they could go to the Lighthouse tomorrow. (29)

Mrs Ramsay: How do you know? The wind often changes. (29)

Mr Ramsay: Damn you! (29)

… …

Conventional story-telling would largely run the dialogue continuously to keep it as a whole unit, but Woolf, as if constantly pressing the pause button of time, inserted between the lines the complex thought worlds of various characters and their interactions so that it stretches for more than twenty pages. Kavaloski comments that Woolf “transgresses convention” in order to create a world of fracture and discontinuity (126-127); however, the lines of dialogue, although scattered, are also always picked up and serve as the threads to rein the wandering consciousnesses back on track, and the result is not fragmentation but a deep connection. This is also an example which typifies Woolf’s tunnelling technique, precisely due to which the novel is crafted incredibly spacious, despite condensed time and place.

A Story Not by Plot but by Themes

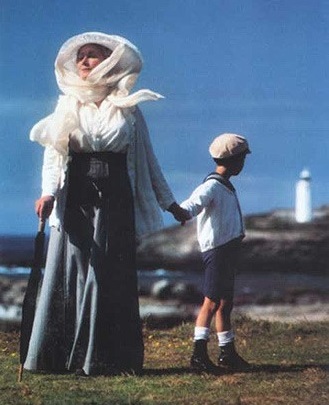

The three parts of the novel also have distinct traits of their own. Part I “The Window” is virtually static, placing Mrs Ramsay sitting at the window as its focal point. The narrative world and its characters are depicted mainly through Mrs Ramsay’s eyes, while the eyes of the other characters also look towards Mrs Ramsay to offer multi-personal perspectives. The radiation from the luminously transparent centre and the multiple responsivenesses to it constitute the main shape of this part of the novel, while two threads run hidden beneath: the journey to the lighthouse and Lily’s painting.

The hidden themes emerge to the surface in “The Lighthouse,” intertwined, to form the ligature of Part III, where Mr Ramsay along with his two youngest children accomplishes the sea voyage, while Lily completes her own quest for the meaning of life, externalised as the completion of her painting. The two quests are described alternately, woven together through Lily’s actual vision of the boat and her mental picture of its progress. They reach simultaneous completion in the last chapter, with Lily first loudly announcing about Mr Ramsay’s journey, “He must have reached it,” “He has landed,” “It is finished!”; and then about her own painting, “It was done; it was finished.” The third part of the novel, then, does presents the trajectory of the themes and provides a closure in the absence of a traditional plot.

It is in the second part, “Time Passes,” however, where Woolf’s originality in form and style most shines through, and which can be most fittingly called an “Elegy”––the term Woolf herself used to define To the Lighthouse to replace “novel” (Diary 34). The brief chapter one depicts the characters retiring to sleep, in the reign of darkness and with the hope for the return of light (McNichol 16). These themes then unfold in the following chapters with the passage of time, which is portrayed in at least two ingenious ways.

Firstly, Woolf depicts the passing of time without depending on the conception and experience of time by human characters; instead, natural elements and inanimate objects are personified to take on human thoughts and feelings, functioning as the tangible agents of the shapeless forces of destruction and decay on the one hand and order and renewal on the other. The rich symbolism blurs the boundary of novel and poetry. Darkness takes on the shape of flood water––an “immense” “downpouring”; and “nothing stirred” in the house except the airs “detached from the body of the wind” (103). The incorporeal darkness and nothingness are given personalities through verbs associated with human activities; they “stole round,” “crept round,” “entered” the dilapidated house, “toying” with hanging wall-paper, “questioning and wondering” (103-104).

For sure, humans are also present in the figures of Mrs McNab the char lady and her companions; however, they are not treated as characters but symbolic forces of order countering chaos and of life countering death. It is through the reminiscing of Mrs McNab that the Ramsays––especially Mrs Ramsay––were preserved from the death of oblivion, and through her work that the house delivered from disintegration:

…the whole house would have plunged to the depths to lie upon the sands of oblivion. But there was a force working; something not highly conscious; something that leered, something that lurched; … Mrs McNab groaned; Mrs Bast creaked. …Mrs McNab, Mrs Bast, stayed the corruption and the rot; rescued from the pool of Time that was fast closing over them… some rusty laborious birth seemed to be taking place, as the women, stooping, rising, groaning, singing, slapped and slammed … (114)

Here Mrs McNab and her friend are described as “something not highly conscious” and in a style similar to that in which the personified invading airs are described. If darkness is the devouring flood, then the char ladies––leering, lurching and creaking––are the dilapidated, repair-needing, but nevertheless life-restoring ark in the storm (Ellman 100).

Secondly, “Time Passes” depicts the passing of time without following major events in chronological development as do other novels. If chapter two describes the darkness of one night, the following chapters present night as if a pack of cards were being dealt out “equally, evenly” by the “indefatigable fingers” of winter (104). From one night and many nights in one winter it fans into years portrayed through images and impressions of rotating seasons. A series of close-up moments in time: the deaths of Mrs Ramsay, Prue and Andrew, brings the span of years into focus (McNichol 22). However, tragic deaths and war, which would receive detailed treatment as major events in conventional novels, are simply bracketed and embedded in the background.

Fragmentation or Unity?

Kavaloski sees “Time Passes” – the middle part of the novel – a “structural act of interruption” (132), which shows that for Woolf “the unity of the whole is ultimately unattainable” (138). But a corridor divides and connects at the same time. Despite the disruption, it brings the two blocks into union and continuity. Woolf made Part I “The Window” occupy a September evening, and Part III “The Lighthouse” a September morning, as if saying that life for the characters resumes after a long interlude of dreams. There are many signs that Woolf intended to create a continuity. “The Window” begins with the word “Yes,” and so does the last sentence of “The Lighthouse” (Bradshaw xliii). Part II “Time Passes” opens with the characters going to sleep one by one and light being extinguished, and closes with Lily stirring in her sleep and waking in the morning. In “The Window” the idea of a journey to the lighthouse is entertained, and Lily’s painting is deliberated in her mind; in “The Lighthouse” the journey is undertaken and the painting accomplished.

In addition, the two blocks are intentionally connected through many recurrences of symbols, metaphors and motifs: the water, the lighthouse, the fisherman, the image of Mrs Ramsay knitting her reddish-brown stocking, the metaphor of the wooden table in Mr Ramsay’s philosophising, to cite only a few examples. Most significantly, Mrs Ramsay remains the central figure throughout, in physical reality in “The Window” and in the reality of other characters’ consciousness in “The Lighthouse.” Thus Woolf succeeded in weaving a fabric of unity and coherence in a manner that breaks completely from the conventional form of lineal scaffolding, plot development, resolution and denouement.

Virginia Woolf was clearly conscious about the rupture between conventional novels and her own To the Lighthouse. She confessed in her diary the intention to invent a new name to supplant “novel” (Diary 34). Her quarrel with the conventional novel form was that it constrains the writer from seeking what is life––what she called “the essential thing,” “spirit, truth or reality” (“Modern Fiction” 105-6). For her, this truth cannot be obtained from lifelike imitations of the external world, but is only found within the complexity of the human soul and heart, and it is the aim of the artist (including the novelist) to puzzle out human destiny and the meaning of life (Handley 3). This is the task and the content of her novel To the Lighthouse, and its form serves her purpose. Through the unique, symbolic structure with embedded multi-layers of characterisation, Virginia Woolf portrayed the dual nature of life: ephemeral and empty but also loveable and triumphant; in so doing she gave the novel form a rebirth.

Works cited

Cohn, Ruby. “Art in To the Lighthouse.” Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 8, no. 2, 1962, pp. 127–36.

Ellman, Maud. “A Passage to the Lighthouse.” A Companion to Virginia Woolf, 1st ed., edited by Jessica Berman. Wiley, 2016.

Handley, William R. Virginia Woolf: The Politics of Narration. Stanford University, 1988.

Kavaloski, Joshua. High Modernism: Aestheticism and Performativity in Literature of the 1920s. Boydell & Brewer, 2014.

McNichol, Stella. Virginia Woolf: To the Lighthouse. Edward Arnold, 1971.

Woolf Virginia. To the Lighthouse. Edited and introduced by David Bradshaw. Oxford University Press, 2008.

––. To the Lighthouse: The Original Holograph Draft. Edited by Susan Dick. Hogarth, 1983.

––. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Vol. 3. Harcourt, 1980.

––. “Modern Fiction.” Collected Essays, Vol. 2. Hogarth, 1966, pp. 103–110.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

This was the first Virginia Woolf novel I read, and when I finished it I knew I’d want to read it again. The characters were curious, Woolf’s style was challenging, and after I realised that the plot wasn’t the most important thing there and knew what to concentrate on, I found the book very absorbing.

It’s been a while since I read ‘To The Lighthouse’ and I don’t remember much of it!

How funny. I’m reading this book now. Lovely article. I’m looking forward even more to finishing the book.

This is the first Virginia Woolf novel I have ever read. I found it complex, and at the same time uncomplicated. It makes me think of authors like Marcel Proust, Henry James and James Joyce.

Yes, they are all modernists, difficult but satisfying reads.😀

I love this novel. I feel it is about the basic themes of human existence: love, happiness, the passage of time and the quest for meaning.

I certainly agree!

This is one of the greatest novels by an English novelist ever.

Yeah Woolf is one of a handful of genuinely great English novelists.

I remember reading Mrs Dalloway at 17 to avoid doing ‘real’ work in the college library. I then moved on to ‘To The Lighthouse.’ What I feel I discovered from Woolf was the grandiosity we place on our own lives and at the same time how microscopically small our impact is on the world. But, no matter how small an impact, it is important. That is what ‘To The lighthouse’ means to me.

And there was me naively thinking it was about the inevitable loneliness of existence. Great article.

There’s a 100-word sentence on the very first page.

Looks like the typical tripe my parent’s generation liked to read. It goes on and on and on and on and boringly on…

The same page also contains an unannounced shift from one third-person to another, which these days is regarded as crap writing. In the second page we see “What he said was true.” and this occurs after two different male persons have been referred to: this error is an ambiguous pronoun.

By the look of it the text is absolutely riddled with grammar errors.

Regards, a novelist

Heaven only knows what kind of novelist you actually are if that’s all you can muster to say about Woolf

Evidently, you are a man who hasn’t published anything; nor are you likely to, judging by what you think makes a good novel: impeccable grammar & a gripping story. Good luck in your quest.

You need to know, however, that even if you publish anything it will be consigned to the merciless lethe of history; Woolf, seventy years after her death, still produces hundreds of PhD theses every year, around the world; she has academic conferences & other colloquia dedicated to her work on an annual basis; over 400 books are being published about her her every year. Now, if you think she’s rubbish, the problem may lie with you, what do you think?

You can say, I suppose, that your aesthetic trajectories will never meet; but to dismiss her like that shows immaturity, lack of breadth, lack of imagination and, well … knowledge; and these are hardly the stuff which makes a good novelist…

Tell me about it.

All these academics who bang on about modernism seem to have overlooked the fact that they were all shit at grammar and punctuation, which as any novelist like yourself knows, are the two primary aims of literary art. Woolf didn’t seem to know who was meant to be speaking when. Faulkner didn’t know how to use commas, and Beckett and Kafka had never even heard of paragraph breaks. Joyce couldn’t even spell, for chrissake!

Thankfully this is now all safely behind us and we have luminaries such as Ian McEwan and Jonathon Franzen who are quite good at grammar and punctuation. Phew.

It seems to me that VW novels are hardly ever about the plot.

So true. It’s hard for me to remember the plot of any of them without some serious effort. What I remember are the insides of the characters’ heads and the artistic manner in which the characterizations and plots are presented. What is the plot of the Waves? I’ve no idea.

The way I read To The Lighthouse was that it was a book with a plot that concerned family holidays, but which was written to use that as a vehicle for all the ideas that the above-the-line author apparently rejects.

This novel made me laugh, but not for the regular reasons. I laughed because I had to re-read whole swaths of the beginning because I swore I was going mad.

Thanks for reminding me of this novel. I’m certain that I’ll re-read this again some time, and I’ll probably re-read it several times during that sitting, too.

Woolf is impossible to contemplate.

I feel this novel is a work about communication and about relationships. It’s about the spaces that exist between people – the gaps between speaking and understanding – and about the ways in which people are sometimes able to bridge those gaps.

Love seeing this article on the site! It was a pleasure to edit, and I’m looking forward to seeing what you do next! Great thought-provoking article!

Thank you kindly!

I had to read the book in school.

After page 25 I gave up. One of the worst reads I’ve ever come across. She constantly names and refers to her characters by letters. This, coupled with never-ending sentences, put me off V. Woolf and stream of consciousness for ever. Goodness what a bore!

Woolf’s style is deceptively simple. There are descriptions of landscapes and everyday events, and yet this author reaches much deeper into the human mind.

Absolute marvel of a book.

Now I love the book even more deeply – reading it is like a meditation.

As I’ve grown older, I’ve realized that Woolf is a pleasure best left for later in life, after the sheer novelty of experience has been burnished into a soft, many-sided glow. 😀

That’s a lovely image, “burnished into a soft, many-sided glow”. 🙂

This novel is like a mirror, but shattered into a thousand viewpoints all reflecting back an unknown part of yourself. Not sure if that makes sense to you, but it does to me.

I attempted reading To The Lighthouse at least twice before, and each time I failed to connect with what Woolf was doing. I will try again after reading this article.

The best stream of consciousness novel I have ever read.

This book is absolutely beautiful. And I can’t find a better description for it. Thanks for covering Woolf and this novel.

It’s the mesmerizing long sentences that got me in this novel.

She gets so very many things right in it! It never fails to move me.

Woolf is a national treasure.

Some of the sentences Woolf puts together make Cervantes and Pynchon look like Dr. Seuss.

Hahaha. Indeed.

Woolf is an author that I consider a wonder.

This is the most domestic of what I have read of Woolf.

Just read the book. It took me longer to read than such a short book probably should have. 😀

Very beautiful and painful book.

Great analysis of a complicated book from a complicated woman. There is some real wealth in exploring what the modernists started in literature and that still continues to be explored in hybridisation today. Thanks for sharing.

Great, thorough analysis. Virginia Woolf is one of those authors who has intrigued and intimidated me for years. I’m not sure if I’d like To the Lighthouse. I tend to enjoy stories with defined, growing characters who experience actual plots. That being said, I give Ms. Woolf all kinds of kudos for creativity, and admire her courage at penning such a story and getting it published. I think she was ahead of her time and would’ve found a lot of like-minded people among today’s authors.