The Making of Middle Earth and its Mythos: Subcreation vs Allegory

Subcreation, a term coined by J. R. R. Tolkien, is at its core built on philosophical ideas of perception and imagination, with emphasis on their effect on storytelling. In Tolkien’s rendering, subcreation is aimed at the formation of a world that is believable within its context— allowing the reader to accept the story as a reality in a “second world.” Middle Earth and the encompassing world of Arda were constructed with this ideology in mind. Subcreation is described as both a process and a product— the process being the creation of a world and the product a theme within the story itself. Tolkien aimed to effectively utilize both aspects in his construction and content of Middle-earth. Tolkien was often very vocal in his pursuit and defense of subcreation; this is seen in his academic work, most notably his essay and revisions of “On Fairy-Stories,” as well as in many of his letters spanning his career as a builder of worlds.

His statements on subcreation were often supplemented with a notable degree of dislike of allegory and its forms. In further study this seems only natural as Tolkien’s definitions of subcreation and allegory are essentially at odds with one another. Allegory, to Tolkien, worked to diminish the power of subcreation and constrained the secondary world as well as the view of the reader. Inversely, subcreation in Tolkien’s aim was based in entertainment and the creation of belief allowing the readers understanding, clarity, and applicability rather than blatantly warranting interpretive views on moral and other issues. Tolkien’s use of subcreation allowed him escapes from allegorical trappings through the emphasis on a broader scope— in essence creating a world that is equally allegorical to the “primary” reality of everyday life.

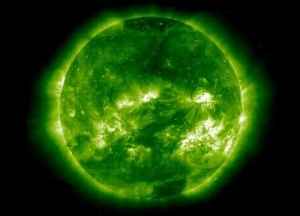

Tolkien’s explanation of subcreation is the use of derivative knowledge on the part of the reader for the purpose of the formation of new worlds; that is to say the construction of aspects of the story are constructed from pieces from known reality: “Fantasy is made out of the Primary World, but a good craftsman loves his materials and has a knowledge and feeling for clay, stone and wood which only the art of making can give” (Tolkien 59 “On Fairy”). A popularized example of subcreation is the image of a “green sun” in which the mental image of “sun” and “green” are superimposed on one another to form an element of subcreated fantasy, creating a new image from existing elements. However, subcreation is not successful until this surreal composite becomes credible in a “Second World” (Wolf 35). Likewise, Tolkien’s role as a subcreator is essential in his formation of Middle-earth in all of its aspects, enabling many to accept Arda as a “believable” world. In this way, the mantra of “suspension of disbelief” need not apply to subcreation.

Tolkien believed that, used correctly, subcreation warranted not the suspension of belief, but rather, belief itself. Subcreation in effect created a world separate but tangential to the known world, allowing it to be governed by different rules and consisting of different realities. Tolkien termed this conceptualized setting the “Secondary World.” To this effect Tolkien stated that rather than the “willing suspension of disbelief” it is the “success of a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “true”: it accords with the laws of the world” (Tolkien 37 “On Fairy”). Tolkien’s role as subcreator is seen in all aspects of his world of Arda and the Mythos of Middle-earth and this mixture of reality and fantasy is what enables the author:

[A]ll carefully fit into a framework of climate and geography, familiar skies by night, familiar shrubs and trees, beasts and birds on earth by day, men and manlike creatures with societies not too different from our own […] the reader walks through any Middle- earth landscape with a security of recognition that woos him on to believe in everything that happens (Kocher 118).

Not solely for the purpose of construction, subcreation is also seen within the stories themselves, particularly in The Silmarillion. The creation of Dwarves and the perversion of life by Melkor are acts that formed new creatures but not solely by the hands or instruments of the smith requiring God (in context Ilúvatar) to inspire in them life.

While subcreation inspired Tolkien’s mythos and the land of Middle-earth, the author’s aversion of allegory influenced the realm arguably equally. Tolkien was extremely vocal in his distaste for allegory and didactic writings as seen in his many letters to editors, critics, colleagues, and fans. He blatantly declared in one correspondence “I dislike allegory,” and went on to say in a backhanded admission that “of course, the more ‘life’ a story has the more readily will it be susceptible of allegorical interpretation: while the better a deliberate allegory is made the more nearly will it be acceptable just as a story” (Tolkien 145 Letters).

It is evident in this that Tolkien’s approach to writing did not fit well with the set story line or archetypal characters that are the typical path of allegorical texts. This makes sense when considering the method by which Tolkien wrote his mythos as touched on in several lectures presented by University of California, San Diego’s Tolkien Scholar, Professor Stephen Potts. Put short, Tolkien’s method of gradual development, piece by piece rather than by means of a rigid story board, would take an entirely different route had Tolkien had in mind a definitive message. Still some have found allegory in his works, claims which he consistently denied much in the way of this reply to a magazine editor regarding a forthcoming book review in which he stated that “There is no ‘allegory’, moral, political, or contemporary in the work at all.” Tolkien continued offering a view of his beliefs on his books and philosophy on his craft:

I hope you have enjoyed The Lord of the Rings? Enjoyed is the key-word. For it was written to amuse (in the highest sense): to be readable.[…] It is a ‘fairy-story’, but one written- according to the belief I once expressed in an extended essay ‘On Fairy-stories’ that they are the proper audience- for adults. Because I think that fairy story has its own mode of reflecting ‘truth’, different from allegory, or (sustained) satire, or ‘realism’, and in some ways more powerful. But first of all it must succeed just as a tale to excite, please, and even on occasion move, and within its own imagined world be accorded (literary) belief. To succeed in that was my primary objective ( Tolkien 232-233). This passage speaks to the goals that Tolkien, compared to his subcreationist approach, found unavailable in the realm of allegory.

Tolkien’s views of subcreation and allegory arose due to the inherent differences in their purpose in respect to writing. In Tolkien’s definitions subcreation and allegory opposed one another in aims he deemed were necessary for good fairy stories. Tolkien valued entertainment and the immersive display of truth over serving to decree standards of morality. To some extent the wide scope of Middle-earth fostered by the subcreation goal to form a believable world worked to disallow the possibility of clear and distinct cases for allegorical purpose. Tolkien opted instead for accounts with dilemmas for which there is not such a clear distinction, and he used subcreation to ensure his disuse of allegory in this way. Tolkien’s aim to create an entire world to use as setting was meant to mirror the real world, not to highlight symbolism as distinct meaning. So much so was Tolkien’s aim that when asked whether or not Orcs were symbolic or communists he replied “There is no ‘symbolism’ or conscious allegory in my story. To ask if the Orcs are Communists is to me as sensible as asking if Communists are Orcs” (Tolkien 203 “Letters”).

The understanding of Tolkien’s views of subcreation and allegory displays the interaction between the two stylistic forms of writing. The analysis unearths some of the underlying means by which Middle-earth was constructed. Tolkien’s view that allegory is not a function within his world is underscored in this want of subcreation. Such comprehension of intention enables the reader to understand and appreciate Middle-earth in its purposes as a world, rooted in our own, rendered fantastic.

Na lû e-govaned vîn!

Work Cited

Kocher, Paul . “Middle-earth Imaginary World?.” Tolkien, new critical perspectives. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 1981. 118. Print.

Potts, Stephen W.. “LTWL 120, Popular Literature and Culture.” Tolkien and Middle-earth. University of California- San Diego. Center Hall, La Jolla. 2014. Class lecture.

Ryan, J. S.. “Creation of a Story.” Tolkien, new critical perspectives. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 1981. 37. Print.

Tolkien, J. R. R.. Tree and leaf. [1st American ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 19651964. Print.

Tolkien, J. R. R., Humphrey Carpenter, and Christopher Tolkien. The letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981. Print.

Wolf, Mark J. P.. “Worlds within the World.” Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation. New York: Routledge, 2013. 35. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Sharing this article to my friends who may be interested in the developments of a great mind.

Thanks! Yes, please do!

As someone with a fair amount of Tolkien knowledge (having read the Lord of the Rings ten times and the Silmarillion twice), I can be somewhat of a curmudgeon when it comes to those who have seen the movies without reading the actual books. However, there is nothing wrong with having been inspired to explore the books by having seen the movies.

Having grown up reading Tolkien, I do sometimes share this sentiment. Though the films have artistic merit in their own right; I think knowing the original work and the history beyond the scope of the films is still far more rewarding.

Love your article! Tolkien’s deep-seated drive for creation is (in my opinion, anyway) the most remarkable quality of his work, and one that too often goes unremarked compared to his thematic influence on later fantasy. When I was reading his letters and the Carpenter biography, the extent of his care in fine-tuning his world all the way down to the minutiae struck me most. I went to a great lecture by Michael Drout a few weeks ago that discussed formal and thematic textual crossovers between Tolkien’s work and Beowulf, like how Tolkien built in already-lost cultural allusions, mimicking the ones that would have even been lost on the scribe of our oldest Beowulf manuscript. Thanks for exploring the deeper reaches of Tolkien — I’m so glad to see this out there!

Thank you so much! You’re spot on; Tolkien was definitely fond of detail. For me, one of the most striking instances of this was his inclusion of the different dialects of Elvish. Not only did he create a language, but to have a comprehensive history of the diaspora and an understanding of the linguistic branching that followed- is just really impressive. This too adds to the feeling that the world of the narrative (as you mentioned) has a deep built-in history- a testament to the quality of Tolkien’s world building and no doubt one of the major effects of his work in the translation of Beowulf. But I digress. Thanks for reading and for the great comment!

As a linguist myself, I couldn’t agree more! The naturalism of his conlang work is mind-boggling, especially in his feel for meaningful subtleties in philology translated from his academic work. All the way down to the featural representation in Tengwar (multiple forms, no less, not to mention Cirth), it’s a linguistic project that’s likely never going to be equaled. Many have imitated and surely will still imitate Tolkien, but you’re so right that the heart of his work lies in the languages; that’s something irreplicable.

Lots of modern literature has been influenced by old myths and legends (including the popular Harry Potter series), and even by Tolkien himself. He pretty much created the “Fantasy” genre. There are enough original elements that the overall story and setting is still his own.

Very true! There is actually an really interesting section about this in “On Fairy-Stories” (the Origins section) gives an interesting take on the transition of history into myth and even further into an ingredient in a collective “Cauldron of Story.” I actually really wanted to talk more about this in the article, unfortunately it seemed a little beside the point to bring it up in relation to Tolkien’s ideas of allegory. But thank you so much for bringing it up!

I did not have much understanding of world building in his work, so this post was a great start!

Thank you so much! If you are interested in more of Tolkien’s ideas I would highly recommend “On Fairy-Stories.” I probably sound like a broken record/advertisement because I keep on mentioning it, but the essay really does offer an insightful and concise overview of Tolkien’s core ideas of world building. Thanks again!

This is such a great conversation this article contributes to. When people think world building they thing Tolkien and for a good reason.

I completely agree, Tolkien is definitely one of the most prominent examples of world building in the modern literary tradition. Thank you for bringing up this point about the larger conversation! Also thanks for reading!

Tolkien was a magical man in many ways, and must have eaten a piece of cake with a star embedded in it when he was a child.

I’m loving the Wootton Major reference! Thanks for the comment!

Thanks so much for this piece! The Tolkien quote at the end about orcs and fascism is really funny and drives home his ideas against allegory in his work really well. Good read!

Haha I’m glad! It is admittedly one of my favorite snarky Tolkien comments! Thanks for reading!

I am not a writer but I am an avid reader, and I have enjoyed reading Tolkien’s works ever since I was little. Thank you for writing an analysis of Tolkien’s views on allegory and subcreation. It was an interesting read!

Many of my literature classes encouraged audacious allegory as long as it was “supported by the text”. That thinking was fun for a while, but it grew tiresome for me. Too much emphasis was put on the external importance of literature and not enough on the literature itself. We read, first and foremost, for enjoyment. It’s comforting that Tolkien shared this sentiment. I think many English students would agree.

This idea definitely resonates with me. While there are texts that are meant to be read as allegory, to impose allegorical ideas can be almost a little insulting- especially as it pertains to Tolkien’s view of world building. It’s as if to say that the world isn’t whole enough to stand alone. I don’t mean to denounce the reader’s interpretive liberties, but I think a well constructed world should be able to be appreciated by its own virtue. Thanks for reading and for the comment!

Interesting article! Thanks for exploring this facet of Tolkien, the article is really insightful. But what do you think about “Leaf by Niggle?” I read it along side “On Fairy Stories” and it seems excessively allegorical especially for Tolkien. I find it odd that Tolkien would couple it with a essay that could be framed as (just as you put it) “against allegory.” Any thoughts?

Ok I have to say that I struggled with this when I read Tree and Leaf. I came to the conclusion that “Leaf by Niggle” is a rare Tolkien allegory (a point that he admits in his letters I believe.) It is paired with the “On Fairy Stories” because it pertains to artistic craft, and how he regards the process of his own writing. I think it is legitimized as allegory without detracting from Tolkien’s ideas of world building because this short story was less aimed at creating a comprehensive world like Arda, and more concerned with conveying his concerns about artistry. So here we find a distinction between blatant allegory and narrative for the sake of enjoyment. That’s my two cents anyway. Thanks for the question and for reading!

His work breathes a wonderful inspiring atmosphere.

I enjoyed reading this! As a Lord of the Rings nerd I was interested to see what you had to say. Very well done! I had not thought of the subcreation aspects of Tolkien’s works, but it made sense. I was surprised you didn’t touch on the conflict between Tolkien and Lewis as they are “Subcreation vs. Allegory”.

Thanks for the comment, I’m glad you enjoyed it! You definitely know your Tolkien- his views on allegory were a distinct difference between him and his fellow Inkling. I actually really struggled with whether or not I should touch on that conversation but there is just so much to explore within that comparison. Another thing that I wish I was able to include was Tolkien’s religious understandings because subcreation very much venerates his idea of God as the only real creator with everything else a subset of his creations. Tolkien’s Catholic ideals against allegory in comparison to Lewis’s Christian beliefs is, I resolved, a course of study all its own and would be beyond the scope of this discussion. Still, thank you so much for bringing it up it defiantly very closely related to this discourse and very interesting conversation still to be had!

Honestly, I don’t have much experience with Tolkein, but I found this article really interesting because of the topic and because of its bearing on other subjects. I think subcreation is probably what makes a piece of any writing successful, and I particularly like Tolkein’s distain for allegory. Great read! Well done!

This really is a fascinating article. I’ve always had the sense that Tolkien’s texts seem to actively resist interpretation, but I couldn’t quite pinpoint what exactly caused that. His aversion to allegory and reliance on subcreation is particularly interesting given that it’s his meticulous world building that seems to be the main point of contention between those who love his writing and those who do not. It’s a great example of how varied and fluid readers’ expectations of literature truly are. There’s lots of food for thought here so thank you for that!

Great article! Tolkein was a master world-builder and had the ability to create a world that readers believed to be “real.” And you captured his disdain for allegory well!

Your article actually reminds me of a lecture I went to in Oxford on Tolkien’s mythos. Brilliant piece, thank you for sharing.

Thank you for this contribution. The topic of subcreation seems to be tied to the genre of mythos. I think this is partly why Tolkien’s Silmarillion is a particularly engaging and coherent read. He is building a bridge for readers to touch what was, what is, and what will continue to be. And because he avoids allegory, the truths about what is can be digested by a very broad audience.