Swamps and Bogs in ’80s Films and Medieval Literature

Images and metaphors of bogs, swamps and other wetlands permeate British literature and its language. If we feel stressed we are ‘bogged down’; at the first hint of bad news we get a ‘sinking feeling’; if we feel depressed, we might liken the feeling to a slow and uncontrollable descent into a swamp. Drowning might be quicker and more violent, but death-by-swamp allows us time to feel afraid, to struggle and then (perhaps) to accept our impotence and our fate as we wait for the moment of submersion to arrive: depression can feel like a similarly slow and agonising process.

Swamps and bogs also have a unique and troubling consistency: they are neither absolutely water, nor absolutely earth, but a potentially dangerous mix between the two. On an abstract level, their slippery nature makes them difficult to categorise and therefore unsettles us: as anthropologist Mary Douglas points out, many cultures tend to have ‘schematising tendencies’ which reject the discordant. Stickiness, for example, is perceived as an ‘aberrant fluid’ because it is neither solid nor liquid, just as swamps and bogs are neither water nor earth. On a more practical level, contact with these elements of nature can leave us feeling tainted or contaminated, touched by a slimy residue that might be difficult to get rid of. It is therefore no wonder that authors and filmmakers repeatedly turn to them as useful symbols in their works.

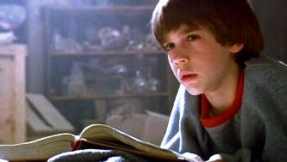

There are two pivotal swampy moments in the cult-status ‘80’s films The Neverending Story (1984) and Labyrinth (1986). Not only were these two films made just a few years apart, they both feature a lead character who is something of a misfit or outsider: Bastian is the bullied, bookish schoolboy of The Neverending Story, and Sarah’s coming-of-age journey is what drives Labyrinth. She is a daydreaming would-be-actress who has trouble growing up and accepting responsibility, continually claiming (like most teenagers) that things are ‘so unfair’. Both films are directed at children (although they are also widely appreciated by adults), and both take place in a fantasy world, where extended allegories and metaphors are repeatedly implemented to help the protagonists grow and develop during the narrative frame. By the end of Story, Bastian has learnt courage, and can stand up to the bullies who tormented him (with a little help from a flying luck-dragon, of course). Sarah is seen caring for her brother and putting away her childish things in a drawer after defeating the goblin-king Jareth, although the appearance of some of the muppets in her mirror right at the end softens the harsh moral of the tale. She doesn’t have to leave everything behind.

It seems something more than a coincidence, then, that both these films decide to introduce swamps and bogs into their fantasy worlds. Yes, swamps and bogs are particularly potent metaphors – but it seems that in these two specific case-studies there is something more at work. This can be partially explained if we recognise the influence of medieval and Renaissance Christian texts on these features. For all their dangers and their ambiguities, swamps are still perceived as threatening, as much now as then; more than this, though, both medieval authors and, it seems, twentieth-century film makers, recognised their specific didactic possibilities. The morals being made in the early books and much later films may be different, but the methods are the same.

Labyrinth and Jacob’s Well

In an anonymous series of sermons from the fifteenth century – Jacob’s Well – man’s soul is compared to an oozy pit, a filthy mire, which should be metaphorically ‘cleaned out’ by good Christians who want to attain a place in heaven after they have died. The ambiguous slime – not quite solid, not quite fluid – is very difficult to remove, and therefore the process will be long and laborious. It is, nevertheless, absolutely necessary. Because the sermons are, to put it bluntly, quite boring, the preacher intersperses his doctrine with entertaining anecdotes that help him make his point and keep his listeners interested. One of these anecdotes tells of a ploughman travelling to a king’s bridal with some of his friends. On the way he gets very thirsty and decides to drink out of a puddle of thick, stinking water – essentially a very watery bog. His friends tell him to wait – he will have wine enough when he arrives at the king’s house – but he is too impatient. For evermore, we are told, the man stinks horribly, tainted by this fetid water. When they arrive at the bridal he isn’t allowed in because he will upset the other guests with his terrific stench. The moral of the story is, of course, patience. Good Christians should shun worldly things and wait for their true reward in heaven: the stinky bog is a metaphor, ultimately, for sin.

This little anecdote should remind anyone familiar with Labyrinth of the fearsome ‘Bog of Eternal Stench’, which Hoggle (the grumpy dwarf who oscillates between helping Sarah and, out of cowardice, tricking her) is terrified of. Not only does the bog smell bad, anyone who so much as touches it will stink forever, much like the impatient man in the fifteenth-century anecdote.

This little anecdote should remind anyone familiar with Labyrinth of the fearsome ‘Bog of Eternal Stench’, which Hoggle (the grumpy dwarf who oscillates between helping Sarah and, out of cowardice, tricking her) is terrified of. Not only does the bog smell bad, anyone who so much as touches it will stink forever, much like the impatient man in the fifteenth-century anecdote.

Here, it might seem, the similarity between the two bogs ends. Labyrinth is certainly not a film concerned with communicating Christian doctrine or ideals, and the bog of eternal stench is a tool used to punish the ‘goodies’, rather than test their faith – none of the characters ever contemplate dipping a toe in it, and they are actively threatened with the possibility by the evil goblin king. The bog is a punishment and a way of cleverly subverting the film’s fairytale elements: when Sarah kisses Hoggle he is not turned into a handsome prince but, very nearly, ‘The Prince of Stench.’

But ‘The Bog of Eternal Stench’ arguably functions on two different levels in Labyrinth. Yes, on a literal level it is a penalty for those who disobey the man-in-charge. However, on another level, it is a symbol which helps drive the moral thrust of the story as a whole, and ties together many of its narrative threads. ‘It’s only forever, not long at all’ Jareth sings to Sarah, trying to get her to give up her quest and continue to live her life as a childish, romantic fantasy. Can it be a coincidence that the bog of eternal stench will also make anyone who touches it stink ‘forever’? Many of the lessons that the characters have to learn during their time in the labyrinth relate to the enduring consequences of bad decisions. Hoggle continually errs on the side of ‘evil’ by almost betraying Sarah because of his fear of the bog. However, we the audience know that if he ever did cause Sarah real harm out of his cowardice, he would never recover: she is his friend and he clearly cares for her, running to her rescue whenever she calls. Such a moral stench would last ‘forever’ and would surely be even harder for Hoggle to bear than the literal stench of the bog. Similarly, the whole film hinges on Sarah rejecting a ‘forever’ in fantasy-land. She very nearly succumbs to Jareth, after eating his poisoned fruit, and again, we as audience know that the consequences would be eternal. She would lose her brother and find herself trapped in the labyrinth ‘forever’, unable to return to reality.

Both bogs, then, are instrumental in making a moral point. In the case of Jacob’s Well, the moral is a Christian one; in Labyrinth it is more secular. But it is clear that both film and sermon-series recognise the potential of bogs to describe and warn against moral taint of any kind.

The Neverending Story and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress

In a later text, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), bogs and swamps resurface and accrue new potency. Bunyan’s ‘Slough of Despond’ enjoys a strong literary heritage – it is referred to in such giants of literature as Wuthering Heights – and has arguably led, or at least contributed to, our modern association of swamps with a depressed mental state. In Bunyan’s famous Christian allegory the ‘everyman’ protagonist (aptly named Christian) is tormented by spiritual anguish, and then visited by a spiritual guide, Evangelist, who tells him to leave his home and seek peace at Mount Zion. Christian dutifully leaves his family and friends behind and sets off on his journey; it is this pilgrimage that the narrative follows.

In a later text, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), bogs and swamps resurface and accrue new potency. Bunyan’s ‘Slough of Despond’ enjoys a strong literary heritage – it is referred to in such giants of literature as Wuthering Heights – and has arguably led, or at least contributed to, our modern association of swamps with a depressed mental state. In Bunyan’s famous Christian allegory the ‘everyman’ protagonist (aptly named Christian) is tormented by spiritual anguish, and then visited by a spiritual guide, Evangelist, who tells him to leave his home and seek peace at Mount Zion. Christian dutifully leaves his family and friends behind and sets off on his journey; it is this pilgrimage that the narrative follows.

Christian has not gone very far before he reaches the first in what will be a series of quite serious setbacks: the Slough of Despond (or, in more modern English, swamp of despair). According to the text, this swamp ‘is such a place as cannot be mended […] for still as the sinner is awakened about his lost condition, there ariseth in his soul many fears, and doubts, and discouraging apprehensions, which all of them get together, and settle in this place.’ The Slough is a representation of Christians’ doubts about the possibility of their salvation; it symbolises their guilt over their sins, and their fears that these sins will mean rejection from heaven. Our Christian, burdened by his own doubts and fears, falls into the swamp; he can’t get out until another allegorical figure (Help) makes him see the swamp for what it really is, and forces him to face up to his fear. A mental adjustment is needed to free him from what is, ultimately, an allegory of the mental state of despair (perceived as a sin in itself, in this post-reformation Christian text).

Unfortunately, another character, in another fictional work, has a less happy fate. In The Neverending Story there is a story within a story: Bastian, hiding from the bullies in a library, starts to read ‘The Neverending Story’ and becomes absorbed in the world of Atreyu, a young warrior, and his horse Artax, who together are trying to defeat ‘The Nothing’, a dark force which threatens to obliterate the world of Fantasia. These two characters are not far on their journey, either, before they reach the ‘Swamp of Sadness.’ As Bastian reads aloud, ‘everyone knew that whoever let the sadness overtake him would sink into the swamp.’ Here, then, we clearly have another metaphor for despair figured through the literary device of swamp. In Bastian’s use of the word ‘let’ we are given a hint at what is to come: Artax, desperately struggling through the swamp, eventually lets the gravity and overwhelming nature of their task (not just navigating the swamp, but saving Fantasia itself) get the better of him. He lets the swamp pull him in and he dies.

‘You’re letting the sadness of the swamps get to you. You have to try, you have to care’ Atreyu pleads, but his words fall on deaf ears as the horse sinks. Not only is this a huge shock in a film made predominantly for children, it is a scene which has also come under attack from a number of critics for its unsympathetic portrayal of the mental state of despair, or even depression. The message seems to be that we actively ‘let’ sadness overtake and consume us, which, it goes without saying, is a dangerous and unhelpful one with regard to depression. Regardless of one’s opinion on this scene (although the critics have a persuasive argument) the important point here is that this ‘80s film uses a swamp in a startlingly similar way to a Christian allegorical fiction written hundreds of years before. And, just as in Labyrinth, the moral drive of Story is tied up in this image of a swamp. Artax becomes a warning, a reminder of what happens if we don’t keep stoically trying, if we give into feelings of despair. Atreyu must learn this lesson on his long journey to find ‘The Nothing’ without his best friend, and Bastian must also learn it: he must eventually leave the library and, following Atreyu’s example, go and face those bullies who threaten him with despair. Christian, the allegorical everyman figure, must learn to keep his faith and not let doubts and fears prevent him from bravely completing his journey, and eventually reaching his reward in heaven.

Conclusions

It would be too much to suggest that the scriptwriters of Labyrinth and The Neverending Story had read these specific earlier texts and deliberately used them as sources. Nevertheless, it is clear that the metaphorical possibilities of swamps and bogs in medieval and renaissance thought, as well as their ability to function as a didactic device, have survived and transformed through the ages, moving from Christian into secular (but no less moral) narrative realms. These swamps and bogs offer a moment of narrative suspense and a choice: characters can choose not to commit a sin, or immoral act and therefore can avoid a stinking taint. They can choose not to give up, but rather carry on and face their fears, whether to save their own soul or, in the case of Story, a fantasy world.

Swamps and bogs continue to provide imaginative material for writers of the twenty-first century. Shrek, one famous example, is forced to venture out on a pilgrimage of his own, to reclaim private ownership of his swamp after it is flooded by refugees from the Kingdom of Far Far Away. By examining the medieval heritage of such imagery we can shed further light on the moral, if not specifically religious, message that these films aim to communicate, alongside their ambition to entertain.

Works Cited

Bunyan, John, The Pilgrim’s Progress, ed. W.R, Owens (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008; first published, 1678)

Douglas, Mary, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London: Routledge, 1996)

Jacob’s Well: An English Treatise on the Cleansing of Man’s Conscience, ed. Arthur Brandeis (London: EETS, 1990)

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I like Labyrinth and The Neverending Story. Both were really good movies and hold up well. Labyrinth ends so ambiguously and I think that’s the way it should stay…I don’t really want to know whether it was all in Sarah’s imagination or whether the Labyrinth was a real place. I don’t care to know exactly how Sarah and Jareth could meet again…some questions are better off not answered.

Interesting piece! David and Jennifer had such great chemistry in Labyrinth!

Thanks! And tell me about it – I always secretly hoped that Sarah would ditch the quest to save her brother and make a go of it with Jareth (spoken like an only child)!

In the 80’s kids movies were frequently dark, dangerous, and sometimes scary.

Never Ending Story, Gremlins, Return to Oz, Monster Squad

Nowadays ever single kid’s movie is just warm, fuzzy, and happy.

There have been dark and dangerous stories for children in recent years – City of Ember, The Golden Compass and Bridge to Terabithia come immediately to mind. There’s also been films like Corpse Bride, the Harry Potter series and Pan’s Labyrinth. The thing is, aside from Harry Potter, none of these darker films aimed at a younger audience have had much success. I think that is more to do with the parents, who are maybe afraid to expose their children to the dark and the mysterious like that.

Agreed. I was a wimpy kid, but even so, they are making movies too purified and fluffy. They rarely even have a solid plot anymore.

all you people that got to grow up in or experience the 80’s are so lucky. everything from then is the best, best movies, best cars, best music, best fashion(in a funny way)

i had to grow up/still growing up in the 90’s and 2000’s. maybe ill look back in 20 years and think this time was cool, but at the moment, no.

the 80’s was a fantastic time to grow up through, best films, music tv etc.. but the period itself seemed more relaxed and people just seemed happier and more friendly overall.

sometimes i wish they would hurry up and invent a time machine as i’d be first in line to buy a one way trip back to the early 1980’s and live it all again.

I was born in 1987, and while I am extremely lucky to have grown up in that era with all of the memorable movies, TV shows, cartoons, toys, books, fashions, fads/trends, etc., that I did, I also wish I could have really experienced the 80s. I absolutely adore the music, films, styles, colors, and almost everything else from the decade, and have been told that I’d have fit in beautifully. Of course, I’ve also been told that I should definitely have been a hippie in the 60s, and that I’d have done very well in the past, generally–born too late, eh?! XD Perhaps, far as I can tell in this lifetime. I’m just a very “retro” type of person…and I usually like it when the past returns and becomes new and “modern” again. ^^

This is really interesting. I honestly never thought about swamps much before reading this article 🙂 Great choice of pictures too!

Glad you enjoyed it. After writing it I keep noticing swamp references everywhere…!

In Neverending Story, something that I laugh at now that I’m (much!) older than I was when I first saw this incredible movie is the scene where Bastian “borrows” the book from the bookseller. When I was younger I was amazed that Bastian took the book even after he was basically yelled at to leave it there, that it wasn’t for him. I know if that were me I never would’ve took it haha.

“Never-Ending Story” is really a personal film for me. It’s not just some nostalgia thing, either. Some movies from the 80s and early 90s I watch and love because of some past adoration I had for them. Often, the love would not translate so well now.

“Never-Ending Story” is not that kind of adoration. As I get older, the movie always means just as much to me as it did when I was a kid, but for different reasons each time. When I was a boy, I used to swear that I would never lose my imagination, never give in to parents and stop drawing my pictures and writing my little stories. Then, as a teenager, I watched this and thought I would never let go of my dreams to an unimaginative and oppressive society. I would never worry about my math classes at school or focus on some boring subject instead of reading a novel on my own, or writing poetry during class. Now, as an adult, I watch this movie and weep at the loss of my own innocence, at the loss of everything that once meant so much to me.

I still write (and am majorly published, to boot), and still try to live my life to the fullest. With that said, though, I can’t help but feel I gave in to the Nothing of this horrible world. I can’t help but feel that all my friends from Fantasia would be very disappointed with me these days. And they looked like good, strong hands.

This movie…it’s just very special to me, and very devastating.

This is a very interesting article! I don’t remember Labyrinth well enough to have an image of the bog scene from that movie in my mind, but your writing makes sense and the parallel to the Christian tale is surprising. NeverEnding Story is one of my all time favorite films, since I loved it as a child and found it an intriguing film even on re-watching it as an adult. The swamp scene is definitely an early climax and it used to always make me cry – you’re absolutely right about Atreyu having to go through this hard sort of “trial”, to lose something and then come out of it stronger.

Thank you! Glad you enjoyed. Any excuse to watch The Neverending Story again…one of my favourites, too.

The neverending story is so weird and so boring.

I liked some of the crazy monsters and glad they didn’t attempt to use computer graphics but the bad outweighed the good largely. Will never watch again.

Well, this is not related directly to this topic, but I can barely express my profound disappointment in The Pilgrim’s Progress. My real disappointment was in the theology. I cannot believe this is classic second only to bible with some Christian readers. I guess my two biggest complaints about the book are one, its hodge-podge nature. I mean understand it is an allegory, but I really could not understand what journey was really being allegorized. I will admit my problem probably stemmed from a core theological difference. I believe we are living at time when we are justified, because Christ has died for our sins. Therefore, I found it strange to see this pilgrim go on this journey, but almost never call on the Lord. He seemed to never pray, and Lord never seemed to be there helping him on his journey. I did not see the Holy Spirit present and working within the novel. I cannot imagine why an author would allegorize our journey and not have the Holy Spirit that was poured out at Pentecost present on that journey. Two, I did not understand how the Pilgrim could arrive at the Celestial City, before the second coming of Christ.

Well written article, I agree with the swamp/bog comparison to despair. I would like to weigh in the wordage of “let” in the Never Ending Story. The word hope needs to be included in the conversation, or lack there of. “Letting” despair happen is intended to illustrate a giving up hope. Sinking in the swamp is thus a byproduct of giving up hope when despair hits.

This is a really useful point, thank you! I absolutely agree that the concept of ‘hope’ is missing in this discussion, and I like that you picked up on that particular word ‘let.’ As I said in the article, I think this can be a troubling one if depression is brought into the mix, but I think what the film is trying to get at through its imagery is more ‘giving up’ than ‘feeling depressed’. Stocisim is what is required, or so it seems in the narrative. Of course we *do* see Artax again, which I forgot to mention in the article, galloping about at the end, which undercuts the message somewhat…! Thanks for your interest and for picking up on something which should be included!

Great piece! I’ve always wanted to watch Labyrinth because the movie features David Bowie, but I’ll be able to finally watch the movie and reflect everything I learned after reading your well-written piece. Nice job!

Thanks Amanda, glad you enjoyed it. And I hope you like the film – David Bowie is amazing in it!

I first read the The NeverEnding Story book and now of course i wanted to watch the movie, but after 10 minutes I stopped watching and close it. I understand that the movie is adapted for the american public, but there are too many changes. I just can’t watch it. I am kind of sad and I think the book would deserve an adaptation similar with Avatar graphic, and of course no changes in the story.

I adore your piece! I love that while you discuss the growing trend from the medieval/renaissance to now, you don’t attribute them as direct sources. Not everyone is like Tolkien, and studies and uses myth so completely haha. Your work here is so great and fascinating. I’m a huge renaissance buff/david bowie devotee and this article is just aces!

Thanks so much for this lovely feedback, made my day! And I was careful to try and present a trend, rather than arguing for the (unlikely) idea that either swamp was based on the medieval/renaissance texts specifically, so I’m glad that came across!! Thanks for reading 🙂

Lovely piece of writing!

Thank you!! Glad you enjoyed.

This is a really interesting an unusual topic. Great job!

Thank you – just an excuse to relive my childhood, really…! Happy you liked it.

Hey, great work, and intriguing topic – I like the way it turned out. I hope you post again!

Thanks for this and for your feedback!! Excited to post the next one…!

Tactile and olfactory sensations are inevitably tied up with the experience of being in a swamp/bog — I wonder what you make of the swamp/bog metaphor being used so often in film, an art form that can produce neither sensation?

Great question! Although I wonder what art forms you’re thinking of which *can* adequately recreate these sensations? I think, although of course very tactile, swamps and bogs really lend themselves to metaphors, both in film and literature, because that sinking feeling is so easy to imagine, and compare to our own emotions. For me, these swamps and bogs, whilst visually very effective are particularly significant because of their more abstract meanings (which are born out of the sensations themselves, of course).

Great article. I like the analysis you made with the literary works. I always joke with my Composition students that I am going to throw their bad papers into the Bog of Eternal Stench! Not many get the reference, though.

I love this comment – made me laugh! I’m going to try that with my students, see how many figure out the reference. Thanks for reading, glad you enjoyed 🙂

Absolutely great idea for an article. I hope you continue along these concepts in your future articles. Reading the Buffy one next.

Thank you!! 🙂 The article was a product of me trying to show my students how medieval texts are still ‘relevant’ and have a lasting impact, and these literature/film comparisons ended up being really fun to think about.

Interesting article, Hetta! As you suggested in your conclusion, I’m not entirely convinced that there’s a strong relationship between Early Modern employments of the bog and contemporary references, but I think you’re right in saying that the swamp usually signals a pivotal struggle of some sort. I’d be keen to read more about the relation between Medieval and Victorian references to the swamp!

Excellent observations here! Even as early as Beowulf, the swamp has been a location with ghoulish inhabitants. That natural space operates similarly to forests in medieval and Puritan literature as well.

I’d love to know who those “critics” are, and what their persuasive arguments say.