Avatar’s Shock and Awe: Technology, Race, and Space

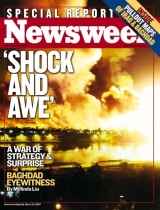

Near the end of Canadian director James Cameron’s Avatar, the sympathetic character Dr. Max Patel (Dileep Rao) says that the Corporation and its private military force are planning “some kind of shock and awe campaign” against the Na’vi. Avatar itself shocked and awed audiences worldwide during its long run in 2009 and 2010 with its combination of live action and computer animation in 3D, and, more importantly, with its story that championed the environment while critiquing policies of the United States government—from wars on Native Americans in the 19th century, to wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in the 21st. It says something about the breadth of its appeal that a movie that featured a military and moral failure by a future United States made $2.8 billion dollars worldwide. In fact, I will argue that Avatar made that much money in part because of its emotionally moving portrayal of these failures. This article gives a brief analysis of technology, race, and space in the highest-grossing film of the 21st century so far. Avatar is a critique of racism, and yet arguably racist, as some have noted, in its portrayal of a white “messiah” who helps save the indigenous Na’vi. Avatar also critiques technology, while at the same time celebrating it. In other words, Avatar’s shock and awe is both visceral and filled with contradictions.

A criticism leveled against Avatar, as Richard Corliss of Time notes, is that “the story may be familiar from countless old movies” (Corliss). But the fact that many can easily read in Avatar echoes of previous Hollywood movies, various science fiction stories, and simultaneously references to American wars of the past and present, is actually what gives it much of its power. Cameron himself freely admitted to drawing on many influences, saying, “I wanted to create a familiar type of adventure in an unfamiliar environment” (Duncan and Fitzpatrick, 15). To attack Avatar for its narrative clichés, in other words, is to attack it for one of the main reasons that it achieved its remarkable cultural resonance.

Let’s begin by looking at Avatar’s central character and entry point, Jake Sully, played by Australian actor Sam Worthington. Jake Sully is a former Marine paralyzed from the waist down, who says things like, “There’s no such thing as an ex-Marine. You may be out, but you never lose the attitude,” and, “I told myself I can pass any test a man can pass.“ Conservative critic Russell Moore wrote in amazement when Avatar opened that “If you can get a theater full of people in Kentucky to stand and applaud the defeat of their country in war, then you’ve got some amazing special effects” (Moore). People in Kentucky were cheering Avatar (I was in Louisville when the film played), but audiences in my home state and in many places were applauding not just because of the special effects, but because the central character is an empathetic Marine—of the “Jarhead Clan,” as Jake calls himself—who becomes pivotal to the movie’s poignant story.

Jarhead Jake also becomes the audience’s hook for Avatar’s exploration of the Gaia hypothesis, which, without being explicitly mentioned, is key to the movie’s setting. The Gaia hypothesis, named after the Greek goddess of the Earth, is a controversial ecological theory that claims that all living things on our planet, through complex interactions, are in a sense one vast active life form. As the theory’s originator, James Lovelock, wrote in 1979, “the entire range of living matter on Earth, from whales to viruses, and from oaks to algae, could be regarded as constituting a single living entity” (Lovelock, 9). In the case of Avatar‘s setting, the planet Pandora, this entity develops a consciousness through its trees that create a brain-like neural network for the communal mind of Eywa, the pantheistic Gaia-goddess of the Na’vi’s home. Through Eywa, Cameron takes the Gaia theory beyond what its supporters claim to create a sentient world.

Why would anyone want to harm this beautiful planet-wide life-form? With almost a wink toward semiotics, Cameron names the reason for the vast American corporate and military presence on Pandora: unobtanium. Outside of Avatar, of course, by definition you can never get unobtanium. But it is a real term invented by rocket scientists in the 1950s (although before Avatar spelled “unobtainium”) to describe an imaginary material with nearly impossible properties that would be incredibly valuable (Hansen, 372). While it might seem like the unobtanium in Avatar is a floating signifier without a connection to anything, that’s not quite the case.

Alfred Hitchcock famously named the motivating element for the plots in many of his films “the MacGuffin” (Spoto: xi), and one reviewer criticized unobtanium in Avatar for being “the ultimate MacGuffin” (Evans). But unobtanium in Avatar is, I would argue, different from a MacGuffin. In Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959), for example, the bad guy played by James Mason has some secrets that he’s stolen from the United States that he’s selling to an unnamed foreign power. At the end of the film atop Mount Rushmore we see that the secrets are recorded on reels of microfilm, which are hidden in a Native American sculpture. But Hitchcock never tells us what the secrets are, because he’s not interested in them. As Hitchcock told director François Truffaut, “My best MacGuffin, and by that I mean the emptiest, the most nonexistent, and the most absurd, is the one we used in North by Northwest….Here, you see, the MacGuffin has been boiled down to its purest expression: nothing at all!” (Truffaut, 139)

Unlike a MacGuffin, which isn’t actually anything important or specific, unobtanium is something concrete within Avatar’s story. As the Avatar wiki explains, “unobtanium is…the key to Earth’s energy needs in the 22nd century.” And so one analogue today for unobtanium might be uranium, which the US and private corporations mined on Native American lands in the Four Corners area—Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona—starting in the 1940s. In the process many acres of sacred land for various Native American nations were polluted, and will never be the same (Environmental Protection Agency). Adding insult and financial hardship to injury, these Native American nations weren’t paid royalties until recently for this exploitation. In Avatar, the devastation wrought by the mining of unobtanium is portrayed as similar to uranium mining. As Cameron said in an interview, Avatar “is about imperialism in the sense that the way human history has always worked is that people with more military or technological might tend to supplant or destroy people who are weaker, usually for their resources” (Ordoña).

And so, unobtanium is a resource that could be likened allegorically to uranium, or perhaps to oil in the Middle East, or any other resource you could name that the US—or any nation—has used its power to exploit. As the corporate hack who runs the operation on Pandora, Parker Selfridge (Giovanni Ribisi), says: “This is why we’re here: unobtanium. Because this little grey rock sells for 20 million a kilo. That’s the only reason. It’s what pays for the whole party. It’s what pays for your science”— he tells Dr. Grace Augustine, the exobiologist played by Sigourney Weaver.

Although Avatar shows environmental destruction on Pandora caused by Earth’s advanced technology, it simultaneously shows the benefits of science and technology, and the film’s scientists are portrayed positively. Again, Jake becomes the audience’s hook as he learns that “good observation is good science,” while he also experiences the benefits of Dr. Augustine’s avatar program. The movie’s avatar technology allows someone’s mind to become one with a Na’vi body, letting Jake walk again in Na’vi form. Dr. Augustine uses this technology to learn about the Na’vi and their planet. Selfridge, in contrast, sees the the avatar program as a tool to maximize the extraction of unobtanium. As Selfridge tells Augustine, “Look, you’re supposed to be winning the hearts and minds of the natives. Isn’t that the whole point of your little puppet show?”

Just as Mr. Knightley in Jane Austen’s novel Emma is knightley, Selfridge in Avatar is selfish—and not just for himself, but more importantly for the Resources Development Administration (RDA) Corporation for which all humans on Pandora work. Selfridge may also have been named after American and British Department store magnate Harry Selfridge (1864-1947), subject of the current British television drama Mr. Selfridge, which premiered in 2013. Harry Selfridge coined the phrase “Only [blank] more shopping days until Christmas!” and sometimes said, “The customer is always right” (Woodhead, 26). But for Parker Selfridge in Avatar, the shareholders are always right. As Selfridge says with glee: “Their damn village happens to be resting on the richest unobtanium deposit within 200 klicks in any direction. I mean, look at all that cheddar!” Selfridge then adds that “Killing the indigenous looks bad, but there’s only one thing that shareholders hate more than bad press, and that’s a bad quarterly statement.”

This brings us to race in Avatar, for as we know the intelligent indigenous creatures on Pandora are up to 12-foot tall and blue, or, as Selfridge calls them, “blue monkeys” and “fly-bitten savages that live in a tree.” The origin of the look of the Na’vi, according to Cameron, is twofold. When he was a young man, just getting interested in a career as a filmmaker in the late 1970s, Cameron’s mother told him of a dream she had one night of a 12-foot tall blue woman (Ordoña). Cameron kept this as an image he wanted to use in a movie someday. When he finally wrote his first full story treatment for Avatar in the mid-1990s, he realized he that liked the color for another reason—it reminded him of the avatars of Hindu deities, which are also sometimes blue, such as Rama and Krishna, who descend to the Earth in material form.

Na’vi seems an obvious anagram for Native American, and all of the actors who portray the Na’vi are Native American or African American. For instance, Wes Studi, a Cherokee who portrayed Native Americans in the films Last of the Mohicans (1992) and Dances with Wolves (1990), plays Eytukan, the Omaticaya’s clan leader, and Neytiri’s father. Neytiri is played by Zoë Saldana, who also plays Uhura in the Star Trek reboot. Cameron’s Na’vi borrow from common stereotypes about Native Americans: they live in harmony with nature, many of them are scantily clothed, they use bows and arrows, and some of the Na’vi warriors go into battle astride Pandoran steeds (Knepp, 215). In keeping with the multicultural melange of references found in Avatar, however, the later Omaticaya chief Tsu’tey (Laz Alonso) also looks somewhat like a traditional Maasai from the East African country of Kenya.

There’s obviously not just race but some racism, even in the idealized Na’vi. This can be traced back to Hollywood’s often bi-polar contrast between “bad” Indians and “good” Indians, and Avatar is clearly drawing on the second stereotype. Cameron cheerfully acknowledged the influence of director Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves as well as other films on Avatar’s story, including Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke (1997), and John Boorman’s The Emerald Forest (1985) (Boucher). There’s even a direct reference to Cameron’s favorite film of all time, The Wizard of Oz (1939), when the military’s leader, Colonel Miles Quaritch (Stephen Lang) says: “You are not in Kansas anymore. You are on Pandora!”—and the rest of the film does have an over the rainbow look and feel to it.

But back to Cameron’s reinterpretation of Hollywood stereotypes of Native Americans. The parallels with Hollywood Westerns go beyond Dances with Wolves, and all the way back to Delmer Daves’ Technicolor Western Broken Arrow (1950), starring James Stewart. In Broken Arrow, as in Avatar, the white main character is torn between two worlds, but ultimately goes native and marries a native woman. In the final shoot-out in Broken Arrow, however, white racists tragically kill Stewart’s Indian wife.

In contrast, that doesn’t happen in Avatar, and doesn’t seem likely for the Avatar sequels that are now in production. Neytiri is not just a fearsome warrior, but one in a long line of strong women central to Cameron’s films, including Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) in The Terminator (1984) and Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991), Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) in Aliens (1986), Lindsey Brigman (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) in The Abyss (1989), Helen Tasker (Jamie Lee Curtis) in True Lies (1994), and Rose DeWitt Bukater (Kate Winslet) in Titanic (1997). Cameron’s earlier heroines, who like Neytiri are strong in mind and body, not only survive but emerge triumphant in his earlier films, and so it seems likely that this pattern will hold.

In any case, in Avatar the conflict between the Na’vi and the mostly white Americans reaches a peak with an important concept that Cameron uses, and which is highlighted in the title of this article: the American military practice known as “shock and awe.” The first time most people heard this phrase was during the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. But the term was coined in 1996 by two scholars, Harlan Ullman and James Wade, working for the US government’s National Defense University in Washington, D.C.

The more technical term for “shock and awe” is “rapid military dominance.” It’s a doctrine based on the use of overwhelming military might utilizing advanced technology to paralyze an enemy and destroy their will to fight. Ullman and Wade’s book states that rapid military dominance will “impose this overwhelming level of Shock and Awe against an adversary….and paralyze or so overload an adversary’s perceptions and understanding of events that the enemy would be incapable of resistance at the tactical and strategic levels” (Ullman and Wade, xxv). The authors of the doctrine admit that it’s nothing new, but something the United States has used before in its history, including in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II, which they cite as a successful application of shock and awe.

In Avatar, the shock and awe campaign is used against the home of the Omaticaya, called Hometree. As the giant tree is destroyed through the application of advanced weapons, it’s not just devastating to the environment, but devastating psychologically to the Na’vi. I think the most emotionally disturbing scenes in Avatar for many people are those where Neytiri and her mother Mo’at, as well as the other Na’vi, are crying in horror after Hometree is destroyed, and several Na’vi die, including Neytiri’s father. Avatar portrays this technologically-induced shock and awe as, at least to some degree, working for a while.

And there is some historical evidence that this doctrine, once in a while and in limited ways, is militarily effective, although at a terrible cost that some Americans have difficulty acknowledging. Even President Harry Truman, who ordered the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, could not admit to himself in his diary that the nuclear weapons were going to kill large numbers of innocent civilians. Truman wrote shortly before the bombs were dropped that “I have told the Sec of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers are the target and not women and children” (McCullough, 537). (As an aside, Cameron said in 2010 that he is planning to make a movie someday about these bombings, titled Last Train From Hiroshima.) Avatar was, in part, trying to get Americans to viscerally understand what it feels like to experience shock and awe on the ground. As Cameron said, “We know what it feels like to launch the missiles. We don’t know what it feels like for them to land on our home soil, not in America. I think there’s a moral responsibility to understand that” (Gardiner).

But what Cameron first claimed is not entirely true. September 11th could be seen as a terrorist shock and awe campaign. And Cameron later admitted that the destruction of Hometree in Avatar “did look like September 11,” and specifically the burning and collapse of the World Trade Center towers in New York City (Hoyle).

In any case, the brutal military campaign in Avatar is one of the reasons Jake Sully goes native. Going native also has a long history in Hollywood that Cameron borrowed from. In the above mentioned movie Broken Arrow, James Stewart’s character goes mostly native and is considered by some whites a traitor to his people. And in director John Ford’s Western The Searchers (1956) starring John Wayne, the character played by Natalie Wood goes native after she’s captured by Indians, and Wayne’s character almost kills her for it. Wayne’s racist expressions about Native Americans and those who join them are similar to what Colonel Quaritch says at the end of Avatar to Jake Sully just before he tries to kill him: “How does it feel to betray your own race?”

But in Avatar the main character who’s gone native becomes almost a white “messiah” who can wage war more successfully against Americans than the natives (Brooks). Something similar happens in Dances with Wolves and a few other Westerns, but in Avatar this subliminal racism becomes even more blatant than in the earlier movies. In a few Hollywood Westerns, white Americans learn from the natives, and help wage war on and then broker peace with Americans, but they don’t exceed Native Americans in their own areas of expertise. In fact, James Stewart’s wife in Broken Arrow laughs at him for how bad he is at using a bow and arrow.

Jake Sully, in contrast, not only learns to ride a difficult “dragon,” but then learns to ride the nearly impossible dragon, Toruk, named “the last shadow”—because that’s the last thing you see before you die. No Na’vi alive can ride this one, but Jake masters it on the first go, and then uses Toruk to help defeat the American military forces. More than that, Jake is the only one who thinks of asking Pandora’s goddess Eywa for help in the war. The idea that only Jake would think of these things, and be the indispensable savior of the Na’vi, almost a messiah figure for them, shows that Cameron could be patronizing to his own creatures. The traditional Na’vi greeting is the phrase “I see you,” which goes beyond sight to acknowledge someone as a being on all levels. In creating his commercially successful narrative, Cameron does not always do that for the Na’vi.

Let’s get back to Kentuckians cheering an American defeat. How was that possible? Well, Avatar hammers home not only that Jake’s a Marine, but also that the military forces he’s taking on are not actually the American military, but a privately-funded mercenary force made up largely of former military like himself. In other words, the movie shows the defeat of an out-of-control Blackwater-style corporate army.

In addition, Avatar was released not just in the wake of the problematic wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but after the financial meltdown of 2008-2009, the effects of which linger on even today. The movie’s message of corporate corruption and greed clearly struck a chord with many Americans, and with people around the world. As unrealistic as many parts as this fantasy film are, the idea of corporate greed leading to failures—economically, militarily, and environmentally—seems to have resonated with many people’s experiences.

Avatar’s representation of space is clearly an analogue for the American frontier of the 18th and 19th centuries, but it’s also a convention within science fiction stretching back for many decades. Recall the original Star Trek (1966-1969), where Captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner) intones at the beginning of each episode: “Space: The final frontier.…” Avatar also represents space as a final frontier for America, rich in mineral and biological resources, but the difference is that it shows the exploitation of these resources as disastrous.

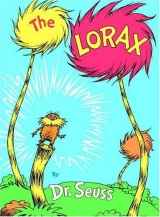

There are probably as many inspirations for Avatar from fantasy fiction as there are from cinema. Cameron himself has mentioned Rudyard Kipling’s “The Man Who Would be King” (1888) and Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter of Mars stories (1912-1940) (Gardner), while others have suggested Poul Anderson’s “Call Me Joe” (1957), a story about a disabled man exploring a planet with a remote-controlled body, and Ursula K. LeGuin’s “The Word for World is Forest” (1972), a story about the intelligent beings of a tree-covered world fighting back against the brutal exploitation of an imperialist future Earth. But Cameron put one book right into the movie, at least in the extended home video version: Dr. Seuss’s landmark children’s book The Lorax (1971).

In the extended version of Avatar, Grace and Jake, in Na’vi form, explore the ruins of the old colonial school for the Omaticaya, and Jake picks up a dusty copy of The Lorax. Grace smiles at Jake as he holds the book, and says, “I love that one!” This praise takes on added significance because Sigourney Weaver has said that she’s essentially “playing Jim Cameron in the movie….kind of channeling him” (Avatar wiki). In Dr. Seuss’s book the title character “speaks for the trees,” and Dr. Grace speaks for Cameron in praising The Lorax, which like Avatar is an allegorical representation of the destruction of trees—and a whole ecology connected to them—for corporate profit. When Jake describes to Eywa what Earth looks like in the year 2154, the year in which Avatar is set, it sounds similar to the desolate ending of The Lorax: “There’s no green there. They’ve killed their Mother, and they are going to do the same here.”

Ultimately, as this article indicates, Avatar‘s shock and awe is as much political as it is anything else. And as the movie became a huge success around the world in 2009 and 2010, a backlash developed that was also mostly political. Typical of the attacks was that by John Podhorestz, columnist for The Weekly Standard, who titled his article “Avatarocious.” Podhorestz was unsettled that Avatar seemingly got many to “root for the defeat of American soldiers at the hands of an insurgency” while simultaneously advocating the “mindless worship of a nature-loving tribe” (Podhoretz).

Some might say that arguments of this kind over any movie grants popular culture an exaggerated power. But in addition to being entertainment, the cinema can sometimes be a powerful forum for the negotiation and understanding of ideas, including those about history, the environment, and politics. Many other Hollywood blockbusters can be read as political as well, and quite a few have messages from the other end of the political spectrum. For instance, as many have recognized, including conservative columnist Ross Douthat of The New York Times, “Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy is notable for being much more explicitly right-wing than almost any Hollywood blockbuster of recent memory” (Douthat). Since Cameron and 20th Century Fox now have three sequels to Avatar in production, and planned for release in yearly intervals starting in December of 2016, the struggle over the meaning and impact of Avatar has just begun, and in fact is almost certain to intensify in the years ahead.

As Avatar was attacked, Cameron embraced the understanding of the film as not just entertainment, but also as inherently political. To the charge that the movie was at times critical of US policies, Cameron answered that “part of being an American is having the freedom to have dissenting ideas” (Lang). He also admitted that Avatar was in part addressing the US invasion of Iraq, saying in 2010, “This movie reflects that we are living through war,” adding that “There are boots on the ground, troops who I personally believe were sent under false pretenses.” Actually, Avatar’s references to the Vietnam War are equally strong, from the jungle environment, to a reference to “daisy cutters” (slang for a bomb used by the US in Vietnam), to Selfridge’s previously mentioned advocacy of “winning the hearts and minds” (Dinello, 161). But what made all of the movie’s references and themes appealing, and therefore powerful, was, as Cameron said, Avatar’s capacity to tap into “a sort of child-like dream state” (Lang).

And, as the movie became a phenomenon in 2010, the dream-world of Pandora and the Na’vi became alluring for many people. A few viewers of Avatar, according to press reports, even got depressed for a while, since they knew that they could never go to Pandora and become one of the Na’vi (Piazza). They felt Avatar to be almost more real and desirable than their own world, in part because of the 3D and the special effects, but more because Avatar portrays a community of beings who live more cooperatively, in a wilder natural environment, and away from consumer culture.

Avatar, as we’ve seen, intentionally offers a narrative of clichés and contradictions. Cameron uses clichés precisely for their familiarity to audiences around the world. In Avatar, advanced technology is both appalling and appealing. The Na’vi function as a sign of otherness and a critique of greed, but are also tinged with stereotypes. Space is a place of opportunity that will lead to the same follies we experience on Earth. The reason so many different people in so many different parts of the world could cheer the Na’vi is because they are not any specific ethnic group or nation, but instead a generalized representation of sentience that is threatened. Cameron and 20th Century Fox made a lot of money in part by making us feel that the Na’vi could be us, and we could be the Na’vi—transcending materialism, while dealing heroically and successfully with militarism and corporate greed. That truly is a far-fetched fantasy, but the overwhelming success of the movie demonstrated that this dream is widely shared, which might perhaps be a measured reason for hope.

Works Cited

Avatar Wiki, “Eywa,” “Fun Facts,” “Unobtainium.” http://james-camerons-avatar.wikia.com/wiki/Avatar_Wiki

David Brooks, “The Messiah Complex,” The New York Times, 7 January 2010.

James Cameron, Avatar, 20th Century Fox, 2009.

Richard Corliss, “Avatar: A World of Wonder,” Time, 14 December 2009.

Dan Dinello, “See the World We Come From: Spiritual versus Technological Transcendence in Avatar,” in Avatar and Philosophy: Learning to See, edited by George A. Dunn, Blackwell, 2014.

Ross Douthat, “The Politics of ‘The Dark Knight Rises,'” The New York Times, 23 July 2012.

Jody Duncan and Lisa Fitzpatrick, The Making of Avatar, Abrams, 2010.

Environmental Protection Agency, “Addressing Uranium Contamination on the Navajo Nation,” 2014, http://www.epa.gov/region9/superfund/navajo-nation/

Barry Evans, “Unobanium, the Ultimate MacGuffin?” The North Coast Journal, 10 June 2010.

Eriq Gardner, “Read James Cameron’s Sworn Declaration on How He Created ‘Avatar’,” The Hollywood Reporter, 10 December 2012.

Nile Gardiner, “Avatar: the most expensive piece of anti-American propaganda ever made,” The Telegraph UK, 25 December 2009.

Theodore Geisel, The Lorax by Dr. Seuss, Random House, 1971.

James R. Hansen, “Engineer in Charge: A History of the Langley Aeronautical Laboratory, 1917-1958”, Washington, D.C.: NASA History Series, 1987.

Ben Hoyle, “War on Terror backdrop to James Cameron’s Avatar,” The Australian (News Limited), December 24, 2009.

Dennis Knepp, “‘We Have an Indigenous Population of Humanoids Called the Na’vi’: Native American Philosophy in Avatar,” in Avatar and Philosophy: Learning to See, edited by George A. Dunn, Blackwell, 2014.

Brent Lang, “James Cameron: Yes, ‘Avatar’ is Political,” The Wrap, 13 January 2010.

Russell D. Moore, “Avatar: Rambo in reverse,” The Christian Post, 21 December 2009.

Jo Piazza, “Audiences Experience ‘Avatar” Blues,” CNN, 11 January 2010.

John Podhoretz, “Avatarocious,” The Weekly Standard, 28 December 2009,

Rebecca Winters Keegan, “Q&A with James Cameron, Time, 11 January, 2007.

James Lovelock, Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth, Oxford University Press, 1979, 2nd ed, 2000.

Michael Ordoña, “Eye-popping ‘Avatar’ pioneers new technology,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 13th, 2009.

Michael Ruse, The Gaia Hypothesis: Science on a Pagan Planet, University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Donald Spoto, The Art of Alfred Hitchcock: Fifty Years of His Motion Pictures, Second Edition, Anchor, 1991.

François Truffaut, Hitchcock, Revised Edition, Simon and Schuster, 1985.

Harlan Ullman and James Wade, Shock and Awe: Achieving Rapid Dominance, Washington, DC: National Defense University, 1996.

Lindy Woodhead, Shopping, Seduction & Mr. Selfridge, Random House, 2013.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

In Avatar 2 they should bring back Steven Lang but this time make him a goodie like the did with Arnie in Terminator 2. Steven Lang was easily the best thing in that movie. A tough as nails Colonel fighting 8 foot aliens on a planet toxic to humans. I was rooting for him in that final fight with Sam Worthington

Avatar? Thought it was a violent remake of the smurfs! Everyone says it’s great so it must be.

This movie is received some bad press from critics. Sure, the story was simplistic–one race with better weapons enslaves another, weaker, race and destroys their land– but it’s a universal one that everyone can relate to on some level, since it has happened in real life throughout history. But the other motif that people are missing is the “paradise lost” concept. In nearly every culture, there exists myths about a Golden Age of man’s history, a time when there was no war and everyone lived in harmony. Humans, as a whole, seem to have a subconscious longing for that Golden Age to exist in reality, and I think the movie hit that particular nerve with many viewers. As for me–well, I think it would be cool to live in the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy universe, or maybe the Red Dwarf one. 🙂

Thanks, V-Duggar, for your comment. Interesting thought about “paradise lost”!

This raises interesting thoughts. As this technology gets better and tactile feedback becomes integrated into the experience , will some people actually spend their whole lives living in a fantasy world rather than the real world? This could actually be the start of a real life ‘matrix’ situation.

How terrific that story-telling and film making can incite such rhetoric.

I don’t understand what people see in this movie. It’s really not very good.

Avatar is among my half a dozen all time favourite movies. It sings hymns to my heart and soul. It is a beautiful piece of work.

Perhaps in the future people will dress as Na’vi… or something like that. There is also the fact that the Language is learnable… The new Klingon!

OOOh, thanks—lovely article. I loved Avatar when I saw it and you deal well with the contradictions in the film, though I think the accusations of racism by various critics were overblown. If anything, it reminded me of Lawrence of Arabia—another outsider indeed, but one who quickly came to identify with the Arabs he was ‘supposed’ to rule over as a British commander. Like the young marine in Avatar, he goes in mufti, adopts a very different culture, identity and ideology as his own and that is how he becomes a leader who helps to unite them. Yes, this is somewhat paternalistic in that the white man seems to have the answers, though Lawrence didn’t actually have the answers, which drove him almost mad; but he had a strong sense of justice. And our marine in Avatar, too, was a wounded soldier who found mobility, nobility and purpose in becoming part of the Na’vi. And in both cases, the central character becomes a leader almost against his own will, but primarily because he deeply understands the imperialist aims of his own country, which he comes to find repugnant and immoral. And this knowledge becomes a catalyst that pushes him to help those who are being oppressed and who cannot fully fathom such evil until it is unleashed upon them. If we move past the stumbling block of the central white male figure taking leadership in each of these situations, we can also read this as an acceptance of the ‘other’, of other cultures that are equal to our own and in some cases better morally. So then the lesson is also one of how a better world can be made when we work together, crossing racial and ethnic lines to find our true humanity. Very thoughtful article, Ben.

Thanks, Rinda, for your comment. I hadn’t thought about the possible parallels with Lawrence of Arabia (which is one of my favorite movies of all time) until I read this. Anyway, thanks for your kind words and insights.

An excellent, very thoughful – and thought-provoking review of the most amazing movie ever made. As I was reading I kept saying ‘yes!’ to myself because your observations were spot on. I was delighted that you made the connection between Avatar and Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Word for World is Forest”. It is one of my most favourite books, yet I didn’t make the connection. The novel I did relate to this movie, however, was “The Inheritors” by William Golding. Wonder what your thoughts are on that? Anyway, well done – and thank you – Ben.

Hi Nikki. Thanks for your comment. I actually don’t know that book by William Golding, but would be very interested to hear about the parallels…Thanks again.

Really fantastic article. Visually, Avatar is beautiful, I get that, but it’s riddled with problems. Though it operates with a pretense of profundity, underneath all the shine and pretty colors the plot is incredibly shallow. The white messiah complex this movie gives credence to is completely inexcusable, and I wonder how much it says about the standards of our society when it comes to race that so many people apparently ate it up without issue. The oppressed don’t need an outsider to come in and enlighten them to their own oppression, that’s not and never has been how revolution works. I won’t even get into the portrayal of minority culture as magical and infallible.

You really nailed it when you got into why it may have been so successful despite the apparent anti-military message. The movie goes out of its way to specify that the soldiers are not representative of the “true” military. In fact, the only person meant to truly represent the American military is Jake Sully himself, a good Marine who takes up the task of liberating a generalized foreign people in peril. Sounds pretty patriotic to me. Anyway, thanks so much for the article!

Thanks, Mariana, for your comment and kind works for my article. You make some good points, but in spite of all of the faults it may have, I still really like the movie! lol

Loved your article! It was insightful, especially when you go into discussion about the main protagonist becoming the “white messiah.”

I’m so glad, Amanda, that you liked the article. I’ve liked your articles too! Thanks for your comment.

Avatar does not stand up to rewatching.

Its like watching a fave childhood programme as an adult.

Let’s look at Cameron’s track record.

Aliens

Terminator 2

Two templates for how to make a perfect action sequel.

I think we’re in safe hands.

Indeed. As you say, Croteau, Cameron has an amazing track record. I wouldn’t bet against him, and I can’t wait to see the next movie he makes.

Many people use the virtual social networks to escape the world they don’t recognize anymore or are tired of, like Second Life or videogames.

I loved that movie–went to see it twice–i can’t explain the joy, the excitement it gave me, just watching those people–wishing I could be a part of tribe. The movie was so –it’s really hard to explain–it just ffilled me with a sense of Joy!

Thanks, Vicenta Bradshaw, for your comments. I agree with you that there’s a sense of joy in this movie that’s missing from most recent epic films.

I want that deep spirituality and connection with my surroundings, something you simply could not do in the concrete jungle without stress…. The movie was so inspiring.

The ‘racism’ in the movie is relateable. Thats why it stings some people. If a tribe in Africa had emerged with superior technology (which definitely could have happened. Look at Egypt’s history) and colonized the planet, that would likely have been how the cultures would have been portrayed. Similarly, as technology and science have advanced, religion has declined. Religion is most prominent in areas where technology and science are considered less important. Many people feel that it is not. This movie does discuss, in an extremely limited way, that struggle. “Soulless” science, or superior morality and harmony through religious ideal. The boundaries are hard. The planet IS a god, and DOES work with its people, and the leaders of humans want to be the “fittest”. Yet, on Pandora, the highest survivability rate comes from adaptation to its environmental and social constraints.

This film reminded me of the children’s film ‘Fern Gully’ same message just updated.

Cameron could shoot the sequel in 4D, so that audiences get the sensation of losing 3 hours of their lives.

That film really does not need sequels. The most depressing thing is that the budget for a film on an Avatar scale could be about literally anything. Why not just make two films equally as ambitious in scale about something completely different?

Great article.

I watched Avatar for about 1 and half hours having bought the Bluray to view it in it’s true splendour for myself.

It still holds my record as the film I have watched the longest but not finished because I couldn’t give a da…

Great films don’t require technology they just require a strong and original story, good writing and good acting.

Once a film has those it can technology but only if needed.

I thought that Avatar was fairly average.

Avatar 2 – Sam Worthington goes to drama school fails to graduate due to unconvincing performances as both blue alien and (especially) human

Avatar 3 – James Cameron begs Gale Anne Hurd to come back and produce his first decent film for two decades and apologises to the world for True Lies and Titanic.

Avatar was one of the best films that I have ever seen, watching the films makes you feel that you are part of the fictional world. It reminds me of the cultural indigenous people of the rainforests in the amazon, congo and Indonesia and how they are fighting for their rights against logging/mining companies in order to preserve there way of life which is a fact. James Cameron has opened up an all new world to modern cinema, he has created a virtual reality that everyone wants to be part, and I think he has done a splended job at this.

Hi Ben. A great article. It made me rethink some of the underlinings in the story as I read the issues you raised. There are movies I have watched more than once inside a movie theater, but Avatar is not one of them, although I liked the movie.

Wow. Very thoughtful. That will take a second read. The only disagreement I think I have is the critique of Jake Sully as “White Messiah.” I believe this is often a misguided form of criticism leveled by some commentators who proceed from a kind of Post-Colonialist default, and that in any depiction of culture clash, depictions of “white people” (whatever that term really means) has inherently racist or culturally-superior overtones.

I don’t think that is what you were doing in this instance, I think you were merely pointing it out as a point of view and presenting the argument.

However, I feel the argument fails in one perspective… the “going native” is not an instant conversion. Sully must slowly come to this. He gradually changes himself; in fact he slowly sheds his “whiteness” as the film transitions to more time of him in his Na’vi avatar and less “in the real world” until he makes a conscious choice to specifically reject the values of his colonial masters and walk away from “humanity.”

In fsct, he cannot become their savior *until* he completly sheds his “whiteness” on a fundamental (yet, not technological) level.

I have always viewed this as an explicit rejection of the “White Messiah” idea, a few dramatic bits of filmmaking not withstanding.

Wow. Very thoughtful. That will take a second read. The only disagreement I think I have is the critique of Jake Sully as “White Messiah.” I believe this is often a misguided form of criticism leveled by some commentators who proceed from a kind of Post-Colonialist default, and that in any depiction of culture clash, depictions of “white people” (whatever that term really means) has inherently racist or culturally-superior overtones.

I don’t think that is what you were doing in this instance, I think you were merely pointing it out as a point of view and presenting the argument.

However, I feel the argument fails in one perspective… the “going native” is not an instant conversion. Sully must slowly come to this. He gradually changes himself; in fact he slowly sheds his “whiteness” as the film transitions to more time of him in his Na’vi avatar and less “in the real world” until he makes a conscious choice to specifically reject the values of his colonial masters and walk away from “humanity.”

In fact, Sully cannot become their “savior” until he finally sheds the last vestiges of his former life, values and culture and entirely embraces the “other.”

I have always viewed this as an explicit rejection of the “White Messiah” idea, a few dramatic bits of filmmaking not withstanding.

Thanks, Josh, for your kind words as well as your perceptive analysis. I think you make some very good points!++ Thanks again.

Great article. Brilliant in-depth analysis!!

The industry, in keeping up with film-goer likes and dislikes, is in a mad rush to transition between technological advancements. Soon, the age of CGI could be bested by greater technology making everything just that little bit clearer. However, practical effects will always have their place, as people continually connect with tangibility over the immediate WOW factor.

Ben,

Thank you for this wonderful article on Avatar. I appreciate you exploring race and racism in this film. This is not a film I would watch on my own because I could see it was another movie where the marginalized characters were going to be doomed in some manner. I don’t need to sit in a darkened theater to identify with marginalization, because I live it daily. While being in a social situation that lacked spirituous libations. I had to endure this film in my sobriety. I did appreciate the CGI and the colors. I can indeed draw from reference to the Hindu deities now that you brought that to my attention. Perhaps this was a nod to British colonization of India. As so many indigenous people have succumbed to colonization and genocide yet those who do survive are then subjugated to the colonizers.

I definitely was aware of the race and racism in this film, and the movie followed some of the popular patterns of white prototypes and archetypes of marginalized people. As you brought out Sully was the white hero, as well he played the part of the intellectual and manipulative roles. The marginalized characters played the archetypical roles as the physical wonder, background figures and utopic reversal so that Sully can have his cathartic moments. Another example you spoke of that is a role reserved for the white character is the riding of the dragon. Sully was the elitist taking reign of another’s culture and demonstrating how superior whites are when it comes to other cultures.

Thanks again for sharing your insight, I appreciate when someone takes a good look at the message’s mainstream media is sending out to Americans and the global messages as well. Perhaps one-day mainstream media will be able to break these stereotypical patterns of characterizations and become inclusive of the other. But for now, mainstream media reflects the ideologies of those who pay the price of admission and purchase franchised merchandise. So why would anyone in a capitalist consumer-driven society want to give that up? So mainstream will stay that way until the society changes its ideologies.

Thanks, Venus Echos, for your thoughtful comments. Much appreciated!

Thanks very much, Thomas, for your kind words!

Avatar was an experience because visually there had been nothing quite like it, set back the stunning 3D vistas and what do you have? One of the most recycled plots in the world, with absolutely nothing original to bring to the table, and some shocking acting.

The white man comes to the natives, poor and happy with their rustic life, to save them from the evil enemy. They end up loving hiim as one of their own . Without him they would have perished. What patronising tosh.

The end half hour is just stupid, endless explosions, screaming, fire and annihilation by the enemy- until they are defeated by the victorious whiteman-turned-native (who never loses his american accent).

Seriously I want my two hours back.

I think the movie was an absolute entertainment, technologically magnificent and good acting!

Graphics were well done, but I have no clue what else was so special with this film? The story is weak and simply a science fiction take on the American Indians and the scene where they all sat swinging together was plain ridiculous and made me laugh. The natives are too aggressive to make you sympathize with them. Naaah. This movie is nothing.

Actually Jake didn’t save the Na’vi, it was Eywa who intervened at the last minute to restore the balance of life on the planet that was about to be altered forever if the RDA succeeded in destroying the Tree of Souls (their direct line to Eywa). All of the action prior to the intervention showed that the natives were no match for the RDA’s firepower. While Jake played a part he certainly wasn’t a saviour, he didn’t turn “native” until the planned destruction of hometree was underway, he had plenty of time to turn and advise the Na’vi well in advance that an invasion was coming which he didn’t do until it was far too late.

In the Blu-Ray extended version of the movie we see him leading a fairly miserable life on Earth and looking for something/anything that would give his life meaning, even if it eventually meant that he would give up his human form and life for something completely different. It wasn’t until he witnessed a company willing to kill in order to mine a precious resource (sound familiar) that he found his calling. The themes might have a familiar ring to them but it’s only because they are repeated so often in real life and in fiction.

It will be very interesting to see where they go from here for the next three movies, Cameron and his team will have their hands full building on the foundation presented in the first movie.

Thanks, Pandora66, for your insightful comments!

This movie was simply wonderful.

WIth 3D, you are more immersed in the sight and sound of the medium, in this case a movie. SIghts and sounds can have a profound influence on many of us, whether it is a movie, music, video games or flight simulators.

Avatar has caused a lot of people to want to become more environmentally aware, and to change their lives for the better.

It seems the media is overblowing this highly expensive, overrated piece of 3-D “magic” to see if it can overtake Star Wars as some sort of cultural landmark in a fraction of the time that it took THAT film to do so.

I definitely look at things differently now. Not everyone was impacted by this film but I was. Impacted for the better.

I clearly need to give this film another viewing. Your in-depth analysis is brilliant and I feel rather shallow for only viewing the film for its effects.

Hello. I feel the same way about how I experienced the film my first (and only) time. I feel as though a second watch would begin to allow me to internalize some of your ideas. A really great insight on a film that I have heard much criticism about. In this case, it will be best understood with a second watch. Thanks for the article, very thought provoking.

Thanks, Jemarc, for your generous comment.

Good article. One thing you missed is the ongoing interest and development of the constructed Na’vi language. It is a big part of the subconscious experience of the film as well as the focus for a large number of devoted fans of the film.

Very interesting article. Personally I am not as fond of the cliches in the movie (I would have preferred it if Cameron infused more originality in the story alongside more familiar plot elements), but I think your writing presents some interesting ideas about how Cameron uses those cliches to create a strong political and environmental message. In ways that possibly makes this movie timeless, which I never really considered before.

This movie was extremely well crafted, and you make some very interesting points that I have not noticed before. Your article is very well written! Thank you for sharing.

Thanks, Nof, for your comment!

It is sad that I still haven’t seen Avatar, but this just made me want to see it more! Awesome article, good job!

This is pure amazing. Thanks for the share.

It is refreshing to read a critical analysis that opens up the movie for the viewer and provides ample material for thought without destroying the viewing experience by providing room for as you put it ‘measured hope’.

Like one sentence said that science has no boundaries, but scientists do have their countries. Nowadays, people talk about the “the global village” more often. When we human beings are encountering some bigger world like creatures from other planet, then we have to be sisters and brothers to protect our living space.

I think the movie is a lot like Andrew Jackson and the Trail of Tears… I think he said something like…. “light a fire under them, and when it gets hot enough, they’ll leave,” when referring to the indigenous peoples of Georgia.

Avatar was just so bad. The character development, especially of the villain and other secondary characters was non-existent. Fern Gully was a more complex story. James Cameron spent all of his time on the visuals and didn’t bother to write good characters, good dialogue, or an interesting plot. Also, why is Grace Augustine’s name so loaded with theological significance for no apparent reason?

You have a serious misunderstanding of MacGuffin. Hitchcock praised his use of something worthless to drive the plot. This was (in his words) his BEST USE of a MacGuffin. Not the definition of what a MacGuffin is.

A MacGuffin isn’t automatically something that is worth nothing. It is a driving motivator and he felt he told a great story with a motivator that meant nothing. But nowhere does he define that as the only thing a MacGuffin can be. In fact it’s in direct conflict with the definition if that’s all that can be considered a MacGuffin.

Probably why he was so proud of North by Northwest. He succeeded in using conflicting story telling to tell a story.

A good essay. Interesting reference back to Hollywood depiction of Native Americans in Western movies.