Clarifying Current Understandings of Fairytales: The Princess or the Goblin?

Few things are simpler than your standard fairytale. Paradoxically, few things are more divisive in the modern age. Are they fluffy princess stories with no basis in reality? Do they foster dangerously unrealistic ideas of life via the “happy ending”? Are the critics right to call them “dark,” “disturbing,” more akin to horror stories for adults than light fantasies for children? Is the violence of fairytales something unsuitable and grotesque? The resolution to these questions hinges upon an understanding–or misunderstanding–of what fairytales are at their core. Rather than asking what are fairytales for, we should ask, why are fairytales the way they are?

Two Related Approaches

By far the most prevalent popular understanding of fairytales is the one we shall call the “Disney Princess” approach. Replete with pink, fairies, baby animals and glitter, this approach understands fairytales as stories wherein the princess (for it’s always a princess) is beautiful, and her prince handsome, evil gets its just desserts, and they all live happily ever after. In this view, a fairytale creates unrealistic expectations through relating the perfect resolution of trouble by seemingly ludicrous magical happenings. Most people subscribing to this view brush fairytales off as only suited for children, while others adopt a more hostile attitude, insisting such “rosy” pictures of suffering and its resolution are actually harmful to children. Fairytales, viewed as an inane flight from reality, are either completely irrelevant or else, highly dangerous.

An antithetical position, generally adopted by those who actually bother to read the original stories, might be called the “Grimm” approach (or better yet, the “Freudian”). The “true” stories, they say, are dark, grim, violent, and replete with disturbing psychological implications, which can only be recognized and appreciated by adults. One might argue it is the most prominent among literary critics of the post-modern persuasion, and has begun to trickle down among the reasonably intelligent folk who remain ignorant of the tales outside of their prominent adaptations (as evidenced by articles with titles such as “The Gruesome Endings of 7 Popular Fairytales,” and variations thereof). Many people who subscribe to this view either know of the ‘real’ stories second-hand, or read them without understanding them. In any case, it too maintains that fairytales are in some way deviant and unsuitable for children.

An Organic Synthesis

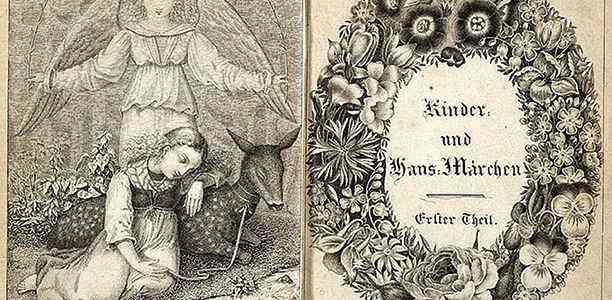

Both viewpoints are mistaken in that they disregard something crucial to the origins of the tales themselves. For fairytales, as any other literary creation, were born within a specific time and informed by that specific milieu. Though first written down in the early nineteenth century–most notably by the brothers Grimm– the stories had been handed down for generations beforehand, dating back to the Middle Ages. Europe in the Middle Ages nursed a predominantly Christian worldview. It was the very air the people breathed, palpable and clear in a way we can neither appreciate nor even fully comprehend in our own diverse world. Therefore, if one examines the tales more closely, one should logically expect to find a Christian sensibility permeating throughout. What those who read or hear of the tales in a more superficial way ignore is the predominantly Christian perspective of the world into which these tales were born.

Now, on to specifics: the claims of both opponents of the fairytale cannot be true. It cannot be both a shallow princess story of happily ever after and a grim psychological fantasy. The truth must involve some combination of both: it is a huge mistake to split them apart and treat them as inherently antithetical. Recalling that fairytales were born into a milieu almost entirely Christian, it is necessary to ask: what, specifically, does that mean? How does Christianity concretely inform these stories? There are three ways. First is the central claim of Christianity: that we were created for friendship with God, but lost that friendship through our own disobedience. Second, God did not abandon us to our own devices, but became man, an infant even, in order to redeem us. And, finally, such redemption was only effected by the suffering and brutal death of the Son of God. Of course, after Good Friday comes Easter Sunday.

With this overarching understanding of human history in mind, we can now reconcile the seemingly disparate threads of fairytale criticism: the happy ending and the violence. Surprisingly, we find that neither is entirely wrong. True, fairytales often contain violence. Yet, it is never violence for violence’s sake, in the way a horror or an action film might be. Indeed, despite some rather gruesome detail (Cinderella’s stepsisters cutting off parts of their feet, for example, or the girl having her hands cut off in Grimm’s “The Girl Without Hands”), violence in a typical fairytale is remarkably understated. If something horrible happens, it is presented matter-of-factly, and is only important insofar as it drives the plot forward. For instance, when the prince throws himself from Rapunzel’s tower and is blinded by thorns, rather than reveling in descriptions of gore and misery, the emphasis is upon their almost tragic reversal of fortune: as Rapunzel has lost her beautiful hair and now wanders friendless in a barren wilderness, so the prince wanders alone and sightless. A fairytale actually functions, up to a point, much like a tragedy—the misfortune that befalls the characters seems an inevitable result of a flaw in either themselves or one close to them.

“…And They Live Happily Ever After”

Which brings us to what may be considered the crux of the fairytale tradition—the happy ending. The happy ending perhaps rankles people more than any other aspect of the fairytale. Some wonder if it is merely a deus ex machina while others deride it as unrealistic tack-on. They say it doesn’t speak to the human condition, since tragedies in “real life” are rarely resolved so neatly. The resolution of a fairytale often appears to come out of nowhere: the blinded prince just “happens” to wander into the same land to which Rapunzel was banished. But recall the context into which these tales were born. Who, out of those who witnessed the crucifixion, ever expected it would turn out well? Who could ever have believed that, not only would all manner of things be well, but that it would be unimaginably better than anything that came before? Who, witnessing the murder of the Son of God, ever expected He would not only rise from the dead, but rise in a glorious triumph for both himself and all those that followed? This sort of reversal of events, from the tragic to the joyful–a “eucatastrophe” as Tolkien would call it–is what any fairytale worth its salt hinges upon.

The fairytale is not meant to give a picture of the world as it is, but the world as it will be. By stripping off the shades of grey and placing matters of life and death, good and evil in naked opposition, the real structure of reality, paradoxically, becomes much clearer. As any good Catholic would tell you, especially in the Middle Ages, Christ has not left this world to its own devices, but shall return in glory at the end of time and finally put everything to right. The fairytale gives a glimpse into this apocalyptic vision. The gruesome punishment of evil–whether by having your eyes pecked out by birds or dancing to death in red-hot iron shoes– rather than a Nietzschean kind of vindictiveness or a Freudian complex unleashed, reflects the eternal judgment of those who persist in wickedness. Likewise, the dramatic reversal in fortune of a pious miller’s daughter and a youngest son reflects the eventual reward of goodness in eternity.

Ask yourself: would the endings of these tales have the same staying power were they not preceded by tragedy? A thoroughly happy story has no lasting effect upon the reader, which is why My Little Pony will never be considered great literature. What makes the happy ending of a fairytale memorable, what makes us return to them again and again, is that, in a sense, it was not supposed to happen. In a true tragedy, Rapunzel’s prince would have wandered, blinded, heartbroken and alone till he died. The fact that he lives–not only lives, but finds Rapunzel and is cured of his blindness—is itself like an act of grace. Unlooked for, often undeserved, they happen nonetheless. For that reason is a fairytale violent, yet sublimely happy.

Were a fairytale not at all disturbing, one would lack a sense of the evil these characters suffer and confront; were the ending not so joyful, the tale would be somehow incomplete. So, on both sides, though they hit upon a grain of truth, most critics miss the whole. The gruesomeness of a fairytale is not evil and darkness for its own sake, but always in juxtaposition with the good. The happy ending of a fairytale, rather than creating unrealistic expectations of life, instead gives a glimpse of the underlying structure of reality in the Christian mindset, giving us hope that the evil we encounter and confront in this life does not go unpunished. Without this fundamentally Christian conception of reality, the logic of fairytales becomes completely unintelligible.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The concept of fairytales was being explored in series 8 Doctor Who.

Fascinating stuff….since the Doctor belongs to fairytale anyway!

Fairy tales have an unfair reputation for negative portrayal of women- the story goes that they’re all either evil crones or simpering princesses waiting to be rescued by princes. This is pure nonsense. The fairy tale genre is packed with heroines who use their courage and quick wits to overcome evil and rescue others. Just think of Gretel pushing the witch into the oven to save her brother, as just one example. Even the evil stepmothers and wicked witches of the genre are at least allowed to be entertaining villains and active participants in the stories, in contrast to the nearly invisible or inconsequential women in so much more recent fiction, even much of that produced to day.

You make an excellent point. I think the idea that fairytales foster passivity and excessive meekness is no more than a myth propagated by watered down versions of theses tales. After all, the heroine of “The Glass Coffin” (coolest princess ever), and even a little girl like Irene in George McDonald’s “The Princess and the Goblin” are far more provocative and dynamic characters than the heroine of a typical rom-com, or “Strong Female Character” in an action flick.

An interesting, well-informed article. Thank you.

An interesting read that makes me reconsider the way I view fairy tales and what they teach us.

Hollywood and fairytales is like one of those old children’s books where everyone is smiling on every page and after a while you start to feel sick or numb and this big blue hole opens up in your chest.

I noticed a shift in fairy tale movies starting with Shrek in 2001. This turned all of the old Disney stereotypes on their heads. The hero was an ogre. His best friend was a talking donkey. He went on his quest only to get rid of everyone and have privacy, not for some noble purpose. *Spoiler alert* The Princess turned out to be an ogre as well. Even Disney got on board in 2007 with Enchanted, where an animated Disney princess, played by Amy Adams in her breakout role, winds up in real-life New York. And don’t forget the TV series Once Upon A Time on ABC (which is owned by Disney), which has fairytale characters interact in the real world. By the way, they had the Frozen characters as their story arc this past fall. The Snow Queen villain was added as an extra character.

I think your observation highlights the trend for fairytale treatments in popular entertainment: most film and television adaptations are more concerned with “reimagining” a tired old story to be more “edgy” or “epic,” forgetting what made the story powerful in the first place. Thus we are given endless iterations of Cinderella while many fascinating and beautiful stories in the vast collections of fairytales languish in obscurity.

Fairy tales have always been grown-up and they’ve always been dark. Many have been popularised in a bowlderised form to try to make them more ‘appropriate’ for children, but the sometimes staggeringly violent, profane and and scary versions have always been out there for adult readers to track down.

I thought Frozen was dreadful, my daughter it was ok, but over rated, we both enjoyed ‘Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart ‘ which unlike Frozen was different from the run of the mill ‘Disney spectacular.’

I agree. The story was rushed. The song was great though.

What would be interesting is to see how the isolation had affected the older sister i a more realistic way.

I’ve always loved Fairytales.

Excellent and thought-provoking as ever!

I really enjoyed how this article turned out!

I think fairytales have been given a lot of flack because people don’t understand the basis of the literature. They teach lessons and morals, and they are deeply fascinating to analyze.

Great job 🙂

More to the point, the fairy takes are not actually read to the extent that they should for such analysis, particularly the lesser-known ones.

Fairy-tales are ultimately a product of their time so that’s likely why the older ones give off the impression of being intentionally “darker.” Back before ratings and censorship, fairy-tales would’ve been meant to be read by everyone. While fairy-tales could be exaggerated in darkness or light as you pointed out here, there always has to be an element of relevance to the world that constructed such stories.

And fairy-tales don’t necessarily have to rely on religion like Christianity in order to convey a moral theme. The tale of “Little Red Riding Hood” was inspired by real issues such as serial killers or sexual predators throughout its various renditions. Charles Perrault’s take in particular had an excerpt at the end that stated his “Le Petit Chaperon Rouge” was supposed to warn young girls about the dangers of men taking advantage of them sexually. Therefore, in Perrault’s case, his unhappy ending of Red Riding Hood getting eaten by the wolf did serve a purpose for more than upsetting shock value, especially since he lived in the 1600s when there would’ve been a greater risk for girls getting raped than in modern times.

In any case though, it seems more like the creator Don Bluth got it correct then with fairy-tales as a structure since his perspective on them matches your statement on the suffering before the obligatory “happily ever after” being necessary for a timeless fairy-tale. Don Bluth stated that his belief was that children could handle darker subject matter as long there was a positive ending to balance it out. Therefore Bluth’s films such as “The Land Before Time” or “An American Tale” follow that similar pattern of Rapunzel where it appeared that there was no hope until that “act of grace” to give hope back to the reader. Your article was intriguing then in how it brought up the perpetual clash between the opposite ends of the spectrum in fairy-tales that seems to be getting deeper as seen from both Hollywood and modern parenting values on what children should or should not exposed to.

Great article!

I’d like to point out, though: fairy tales predate Christianity by thousands of years — and in countries which remain non-Christian.

The first known Cinderella story was “Rhodopsis,” in 1 B.C.E.; another, the story of Ye Xiao, was published in China in the 9th century C.E. In China in the 850s, the predominant religions/philosophies were Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism:none of which even figure a deity.

In Ye Xiao’s story, and other Asian and Indonesian versions, details are eerily similar, including magic pumpkins and golden slippers.

Makes a scholar even more thoughtful: is this Jungian synchronicity, or are there as many paths to God as there are people? These stories have indeed been with us always.

Fairy tales resonate in people’s minds even today. The Lunar Chronicles is a series based on action-adventure retellings of traditional tales.

Great article!

Fairy tales have never been innocent.

The most popular have always been quite shockingly gruesome and violent.

Have you read the original story for Red Riding Hood? She used to do a strip tease for the wolf, and then as new versions were released, the message changed to ‘Be wary of strangers’.

I think most of the people, who have complained about fairy tales offering escapism and encouraging superstition are basing their opinions on the heavily bowlderised versions they are familiar with- in other words they are ignorant of the wider context of fairy tales and haven’t taken the time to read up properly on the genre.

Maleficent was an interesting novelty, but the whole “there are no real villains” thing is becoming a bit cliche now, so it’ll soon be time to move back to the traditional tropes. The TV series Once Upon a Time cornered the market on making it appear that even the worst villains have a streak of good in them, or they’re the victim of poor upbringing, etc. The resolution of its Frozen-based storyline was very weak as a result. But at the same time they resurrected the old “I’m going to conquer the world” trope with another character, who went from being a reformed villain to being more evil than ever, and it felt like a breath of fresh air.

I’d argue that it defeats the point of a fairy tale not to have real villains. It becomes a different sort of tale, just in a fairy tale setting.

In fairy tales, the people (especially the bad ones) aren’t meant to be like real people, or to think like real people. They are just a demon that needs to be conquered by the protagonist (who himself – or herself – isn’t much like a real person either). A fairy tale is a story to enliven you in the subconscious, by whatever means, not a discussion of the nature of people. That’s what give fairy tales much of their clarity and weirdness.

Awesome article, really fascinating subject. It would be intriguing to contrast this with ancient mythology (particularly that of the Greeks). Although there are certainly signs of heroes and princesses in there (Hercules, Perseus), there’s also an interesting degree of moral greyness and very human flaws within their Gods (the punishment of Prometheus being particularly notable).

I like how you dive into the form behind the fairy tale. The “happily ever after” ending is like a rainbow after the storm that the characters suffer. And, it is a promise that good things will always come to those who do good. Cynics can’t stand them XD Things are never perfect in a fairy tale, but that is where grace comes in.

I enjoyed the in-depth look you gave regarding the structure of fairy tales. I remember reading a piece discussing the evolution of fairy tales and how a lot of stories that the Grimm brothers wrote were based off of oral fables passed around the community. I also read that the Grimm brothers had changed a lot of details to fit in with the world they currently lived in. I think that applies to modern retellings (like the ones found in Disney). You made a goof point – fairy tales are significant as they reflect society’s ideals.

That’s so awesome that you tied Christianity into this! I never really thought of fairy tales in light of the Crucifixion…but that’s totally awesome that you used Christ’s suffering and Resurrection as a basis for describing the origin of fairy tales. Awesome post!!!

This is some really interesting work. I think you have really thought about your topic and have offered a very particular opinion. It leaves so much room for discussion that it makes it deeply satisfying to think about. Great job!

What is weird is how much fairy tales focus on women in many different cultures. Not all obviously.

Think of Scheherazade of 1001 nights in arabian/Persian/Indian folk tales, told from the perspective of a female.

Many of these tales do not really delve into the male psyche at all, though generally portrayed as heroic/evil/powerful and or noble, rarely are they the protagonist, nor are their motivations ever questioned or explored imho.

I could of courtse be totally wrong and people list hundreds of folk tales with males being portrayed in a central way, discussing their thought process.

Maybe it’s because I am Welsh but folk and fairy tale has not ever been “bright and shiny” to me. Each tells a morality tale for our times in different ways and the urge to change endings, motives and character suggests an uncomfortable relationship with our own humanity.

This is a thoughtful and interesting article. I’ve been on a quest to unlock the appeal of fantasy imagery and your insight is very helpful. Linking fantasy to the Christian tradition is important as well, Tolkien did the same thing in his essay ‘On Fairy Stoires’. Overall, I really enjoyed reading this.

Isn’t it good that the girls in the new fairy tale animations are not only sweet anymore? Frozen is about sisterhood, the quest for the prince is not so important anymore – good. Tangled gives us a heroine much better at fighting than the handsome guy. Wall-E’s girl friend saves him, not the other way around. Having a daughter I heartily welcome this change. Simply better role models for a girl than damsels in distress, helpless beauties and wicked witches.

real folktales are not usually about real people but archetypes, part of our psyche. one reason why only knowing disneyfied versions is so bad.

Really interesting article. Fairytales have changed so much across centuries, and they are still varying as the film industry takes fairytales we know and changes them heavily to pass on different messages. Moralities are always evolving and this is linked to their social and historical contexts – ‘morals’ of the past are not the same as morals of today.

Fairy tales, especially the original versions, give us hope that despite the horrible things that we may endure throughout our lives, things will work out for the best in the end. Though most of the stories in our common lexicon come from a Judaeo-Christian, European source, they also employ the distinctly Eastern idea of karma: what goes around comes around.

Even in the Disney-fied versions, especially the early movies, the villain often comes to a violent end: the queen in Snow White falls off a cliff, and Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty is killed in her dragon form. Even Ursula in The Little Mermaid is run through by the prow of a sunken ship. Violence is and always has been a large part of our culture, and this fact was especially true in the extremely dangerous world that the stories originated in.

To gloss over and pretty up fairy tales is to do a disservice to the stories and to the people who watch them in their film versions. I’m certainly not advocating violence for its own sake, but fairy tales are more than just stories. They’re lessons, and to take away an integral part of those stories is to take away the wisdom that we can learn from them.

Interesting perspective. Well done.

I think what’s really interesting, is that if someone were to write a fairytale today, what would it involve? Would it include the happily ever after? But if that would occur, then is it really a fairy tale? Or just a tragedy?

I have read and seen both the Disney version of Fairy Tales, and read the Grimm versions of them. And yet, I still did not see the christian undertone of the stories. I do now, thanks to this article, and it makes them immensely more interesting. The parallels between the happy ending of Christ and the happy ending of these characters in fairy tales is evident. But what I still question is what people get out of these “stories”. Can we relate to the fairy tale’s evil and violence because we, as humans, are inherently evil, and then crave redemption which can be found through a savior, be it God or prince? Are we all just looking for a happy ending to life and love to see a character get theirs? And if that is the case, what if there is no one to save us? Is the fairy tale misleading? I would love to explore the that fairy tales have on society, especially if we are exposed to them at such a young age.

This article misses the fact that fairy tales are nearly identical across different culture in structure and theme, despite the differences in environment and religion. The Christian influence is an important argument, yet misses the mark when speaking of origin for the tales. These tales were manipulated by the Christian perception of the world in Europe, yes, but were informed by a pagan approach that in turn was influenced by the evolution of humans and our story-telling as it developed from nomadic hunter-gatherers to the settled agricultural communities we know. In the case of the origin of the fairytale then, we must turn to a theory from Julian Jaynes that speaks to the evolution of the internal voice. That evolution then instructs (albeit beyond our hopes of finding an answer) the origins of these fairy tales. Perhaps a crazy old lady in the woods went cannibal on her grandkids while their father was hunting and when he came back he found a wolf eating the old lady after she ate the children. This story would have spread, been distorted by word of mouth (think of the game telephone) and become two fairy tales that I hope you recognized in this hypothetical situation.

The compromise between both schools of thought (Grimm versus Disney) regarding fairy tales is intriguing, but slightly misguided. The Grimm fairy tales, from which the Disney fairy tales borrow their stories, had the aspects of the tragedy and the “happily ever after” as the article notes. But it is true that the Grimm tales had aspects of both and I argue that the Disney tales simply took those tragic, gruesome aspects out to appease an overly sensitive American culture which wished to repress a key aspect of human nature, which the Grimm tales present – but, as the article said, do not necessarily celebrate or highlight; they simply occur.

The article states that “The fairytale is not meant to give a picture of the world as it is, but the world as it will be.” This assumes that the fairytale is clairvoyant. The fairytale is meant to do neither. The fairytale exists in an imaginary world that does indeed resemble our own, but is distinctly different and magical rendering it naïve to say that it presents “the world as it is” or “the world as it will be”. No. The fairytale is an instruction of the moral compass – including those “happily ever after” tales. This article begins to go in that correct direction, but ultimately misses the mark.

Very interesting topic. I have always been surprised with the original meanings of fairytales, and the way DIsney has always been “cleaning up” the original story. Its interesting to think, as well, that in countries like Russia, the traditional movies/cartoons that follow fairytales are very gruesome, and never sugar coat everything.

Fairytales are poor examples of reality directed specifically at children. Great article, very developed point of views. Many important questions posed in the first paragraph but seemed misplaced due to the quantity. Great eye opener.

Fairy tales, in there basest form, are designed as warnings to children, and instructions. They teach them to dutiful, humble, kind, not to go alone in the woods, and generally have an emphasis on obedience or piety. This focus on instilling virtues as opposed to teaching ties in with why many (but certainly not all) protagonists are heroines. Daughter to this day have responsibilities at younger ages, and more of them, than sons. It would be important to impress upon them the importance of work ethic and sacrifice for the family: think of The Seven Swans, where a young princess locks herself away for years, mute, to sew the magic clothes that will return her seven brothers to their human forms.

Great article!

Fantastic article about balancing out the two polar views of fairytales. Good work.

Disney has a lot to answer for with regards popular perceptions of fairy tales. Traditionaly they were the folktale parables that prepare the young and naive for the cold, dark reality of life. The world isn’t fair and just, people can be cruel as well as kind and there are horrors out there – in the forest, wilderness or even in the street – that you should guard against. They don’t always have happy endings because life doesn’t. They were meant to prepare you for a life among the predators, to teach you that the world is random and dangerous and owes you nothing, to trust no one.

All Disney tells you is that innocence is good and that if you have a good heart you will end up living happily ever after in a sugery coated wonderland… er – no you won’t. You’ll be chewed up and spat out – that’s how the real world works, and how fairytales used too.

A beautiful article indeed, and a great rebuttal to the idea that fairytales are unrealistic, childish, and sugary. As your article points out, the Christian worldview and culture into which fairytales were born are none of these things. Even if a person doesn’t read fairytales through a Christian lens, he or she will recognize both the happiness and tragedy inherent in fairytales if he or she is mature.

Further, one does not need to recognize the Freudian or “grim” aspects of fairytales as their crux to be a mature reader. It helps in some cases; if you’re truly psychoanalyzing Cinderella, you’re probably going to want to talk about the Electra complex, for instance. But just admitting that fairytales are about human characters–even if those humans are archetypes–will, I think, put anyone on the road to great analysis and a deeper enjoyment of the genre.