Sunshine, Celluloid, and Shantytowns: The Hollywood Novel and The Great Depression

In the 1930s, Hollywood, and by extension the city of Los Angeles, transformed from the fledging mecca of a burgeoning industry to a full-on powerhouse. Sound firmly took over the business, as Clark Gable, Greta Garbo, Katherine Hepburn, and James Cagney became household names from Chicago to Calcutta.

Studio execs, such as “boy genius” Irving Thalberg and Louis B. Mayer, were as ingenious, influential, and intimidating as John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie. Akin to the latter, these Hollywood titans were praised as Captains of Industry and scorned as Robber Barons in equal measure. Unlike Carnegie and Rockefeller, the studios did not manufacture products that were essential for both commerce and the subsistence of humankind. Instead, Hollywood delivered entertainment on an unprecedented mass scale, reaching the penthouses of Park Avenue and the slums of Memphis.

The latter, perhaps ironically, were the true engines of the rapid box office grosses accrued during the FDR years. In an era where the official unemployment rate hovered around 25%, the downtrodden in regions across the nation were delighted by the gallavanting Marx Brothers and the seductive sparring of Myrna Loy and William Powell. Mayer and Thalberg may have viewed themselves as humanitarians, the entertainers for the unfortunate, but it is not difficult to discern the profound disconnect between the lucrative films and their impoverished consumers.

This incongruence was clearly noticed by two of the best chroniclers of 20th Century American society. Nathanael West and F. Scott Fitzgerald, by the late 1930s, were as alienated and scorned by society as their characters. Both writers, like countless others, would moonlight as screenwriters. Similarly, both would draw on these experiences in their literature. The resulting works helped cement the consensus image of both Hollywood and the Depression for decades to come.

Literature and The City of Los Angeles: Uneasy Bedfellows

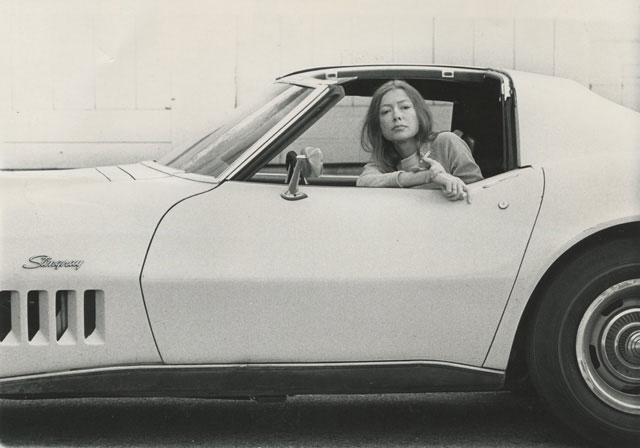

Los Angeles, CA is the second-largest city in the nation, but its status as an entertainment capital is arguably even more secure than New York City. The city of course acts as the epicenter of American film and television, but its music and art scene is nearly as extensive and pervasive. The one area where Los Angeles is often regarded as a bottomless void, however, is in its literature. As the home of noir detective novels, the city is admittedly unparalleled (although San Francisco is a solid competitor). From Raymond Chandler, arguably the hard-boiled mystery writer, to the history-obsessed James Ellroy, the city is legion to great works of crime fiction. However, outside of the city’s first-rate noir, the sunny metropolis is largely known for the works of Sacramento-born Joan Didion, Charles Bukowski, and the underrated John Fante, whose Ask The Dust is perhaps the most accomplished L.A. novel.

All of these writers are essential and brilliant, but the quantity is a remarkable pittance in a sprawling city of striking, beguiling contrasts. Perhaps even more bewildering is the relative lack of literature deeply focused on Hollywood. The great Los Angeles scribes, with the notable exception of Ellroy, seem to view the capital of moviedom as a separate entity never to be mentioned within the same breath of the greater metropolis. This is the equivalent of New York novelists ignoring Greenwich Village or New Orleans authors neglecting to describe Bourbon Street and the French Quarter.

The works of Hollywood literature that are the most enduring, perhaps inevitably, are those written by bemused and transfixed outsiders. Nathanael West and Fitzgerald both came from disparate U.S. regions; West born in Manhattan, Fitzgerald from St. Paul. By the 1930s, in the heart of the Great Depression, the two brilliant novelists were not faring much better than the average citizen. Fitzgerald, suffering from alcoholism and a deteriorating marriage to his lovely, mentally ill wife Zelda, went where many writers have gone and headed west for fortune, if not fame. Around the same time, Fitzgerald’s close friend West joined in on the act of reducing one’s talents to cinematic hackwork. The ultimate result were novels that revealed the opposite ends of the economic spectrum in Hollywood, from the studio bosses to has-been child stars, and offered social critiques as potent and timeless as Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle.

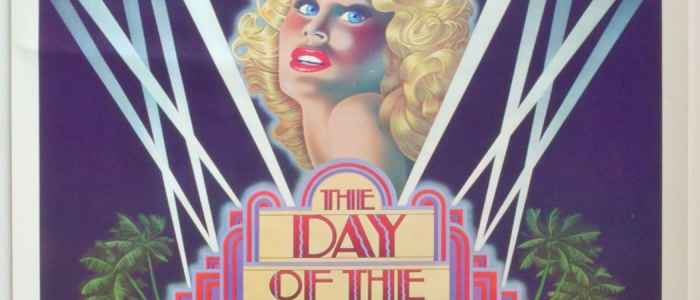

Day Of The Locust: Los Angeles is Burning- And Taking Hollywood Down With It

When one thinks of American novelists who were most prolific between the world wars, the names that immediately come to mind are Hemingway, Faulkner, Sinclair Lewis, and of course Fitzgerald. Nathanael West, however, almost universally gets short shrift. The writer who came into existence as just another New Yorker of Jewish extraction was far from an ordinary novelist. Publishing four remarkably brief but startlingly rich novellas during a decade’s span, West was the ultimate outsider; a satirist when earnest social reportage was in vogue, an absurdist when the naturalistic was treasured.

This guile and sly craftiness are clearly evident in his first two novellas, which are now frequently collected in a single volume; The Dream Life of Balso Snell and A Cool Million. Both are truly singular works of fiction. His next novella, Miss Lonelyhearts, was a comparatively sober and somber portrait of loneliness and the pitfalls of living in Manhattan. This seemingly slight work explicitly reveals the harsh truth that the notion of America as a bastion of social mobility is largely mythical. His next novel, based heavily on his own experiences as a Hollywood screenwriter-for-hire, would eventually emerge as his best-known, and it is today widely considered the best novel ever written about Hollywood. Most images of Hollywood during the 1930s are centered around a heartwarming theme; during this economically disastrous era, it was the movies alone that united the disenfranchised. Whether it was Shirley Temple delighting millions or the Depression-focused comedy It Happened One Night sweeping the Oscars, Hollywood during this decade is largely regarded as a sacred cow.

West, from first-hand experience, dared to subvert this convenient narrative. Day of The Locust is an acidic, nightmarish portrait of not just the empty promises of Hollywood in particular and Southern California in general, but the deception of the American Dream in totality. In this fashion, the novella does for the Depression what The Great Gatsby did for the Roaring Twenties. Centered around one of the most unassumingly tragic protagonists in all of American literature, an aspiring painter named Todd Hackett, Day of The Locust casts a distinct mood that never dissipates.

Largely set in a grungy apartment complex, as always an ingenious setting for a work of fiction, West reveals a side of Los Angeles not visible in brochures or most Hollywood movies. In many ways, Hackett is not an ordinary American citizen; a privileged graduate of Yale, the impressionable artist seeks not a lucrative career, but spiritual fulfillment through the completion of an ambitious painting entitled “The Burning of Los Angeles.”

He sets to work on studio lots, as he meets a variety of aspiring Hollywood players and fading, desperate hangers-on. These fluidly etched characters range from a persistent dwarf, a wanna-be cowboy, and most vividly, an aspiring starlet who sees right through Hackett’s open, sincere attempts at affection.

Unlike John Steinbeck, the novelist primarily associated with the Depression, there are no explicit, heavy-handed references to the era’s economics. There is no mention of the WPA or FDR, no scenes of Hoovervilles or long lines at food stalls. There is also a conspicuous lack of the idealogical sentimentality found in even the best of Steinbeck’s output. Subtly, however, Day of The Locust is as clear eyed and powerful a Depression novel as The Grapes of Wrath. Through his multi-faceted panorama of Hollywood society, West lays bare the artificiality and elusiveness inherent in the notion of America as a golden land of opportunity. In this era more than almost any other, this lack of authenticity is incredibly transparent.

Contradicting the sun, surf, and palm-trees image one usually associates with Southern California, West renders Los Angeles as an expressionistic, nearly Kafkaesque kaleidoscope of garish blacks and disheartening greys. In the work’s unforgettable final image, of a plethora of ordinary citizens rioting over a cinema premiere screening, West speaks to the horrifying truth that glitzy entertainment provokes more heated emotions than social inequality and government corruption. In a contemporary America where protestors in Baltimore or Ferguson are condemned while Red Sox and Raiders fans are praised for erupting into violent mobs, the point West is making is abundantly clear.

Day of The Locust may not be as entrenched in the popular consciousness as Of Mice and Men or For Whom The Bell Tolls, but its vitality and lingering relevance are arguably even more essential.

The Last Tycoon: A Glimpse Inside the Mind of Hollywood Royalty

Around the same period as West’s Day of The Locust, Fitzgerald began writing what would prove to be his (unfinished) penultimate novel. His previous work, 1934’s Tender Is The Night, was stunningly complex and emotionally devastating, with an unorthodox, subversive structure that contrasted sharply from The Great Gatsby or This Side of Paradise. The public dismissed the novel while the critics derided it. It was not until years after the novelist’s death that it would receive a deserved re-appraisal and become regarded as one of his finest achievements.

Fitzgerald’s subsequent forays as a screenwriter would yield a decidedly disparate perspective from West. Ultimately, however, the two writers’ portraits of Hollywood are remarkably aligned, as each skilled novelist subtly uses the film industry as a microcosm for Depression-era America. West revealed the sordid, desperate, darkly comedic travails of the have-nots, while, inevitably, Fitzgerald honed in on the wealthy, sheltered studio executives, who are revealed to be as ruthless and tyrannical as bankers and stockbrokers.

As aforementioned, Irving Thalberg and Louis Mayer were essentially the Rockefeller and Carnegie of Hollywood, and their twin spheres of influence are explicitly clear in The Last Tycoon. The novel’s enigmatic protagonist, Monroe Stahr, is a thinly veiled portrayal of Thalberg, while his abhorred rival and warm ally Pat Brady is modeled after Mayer. Akin to the passive, observant Nick Carraway narrating the larger-than-life saga of Jay Gatsby, the novel is seen through the elusive eyes of Brady’s naive daughter Cecilia. This device allows the reader to simultaneously become ensconced in the minutia of Hollywood corruption while still remaining on the outside looking in. This lends the brief, cryptic work a profound sense of voyeurism.

The focus of the novel, unlike the panoramic Day of The Locust, is uncompromisingly narrow. The Hollywood Hills and coastal environs of Los Angeles are seen through the cruising automobiles of the elite. Passing references to the city’s downtrodden are tossed as throwaway asides by the idle, isolated sons and daughters of Hollywood’s movers and shakers. This is not the result of socio-economic myopia on the part of Fitzgerald, but a testament to his subtly biting satire of the upper-classes. The satirical edge is so muted and implicit that the characters’ socially ignorant nature can be misconstrued as the novelist’s.

This is what makes the novel such a unique, startling achievement; the reader, writer, and protagonist are complicit in the glorifying of the Hollywood lifestyle and the exclusion of the working class struggle. As a reader, it is easy to become dazzled and engrossed by the vicious, visionary entrepreneurship of Monroe Stahr and revel in Cecilia’s glamorous hedonism. Yet, this headlong rush into the industry’s best and brightest ignores the fact that Los Angeles, now and especially in the 1930s, was a cesspool of inequalities and urban poverty. The immersion into the 1% ultimately offers as stinging and potent a piece of social commentary as anything by Lewis or Steinbeck.

The novel studiously documents the era when the moguls and industrial giants were slowly morphing into money-hungry entertainment hustlers. No longer were these captains of industry interested in functionality, usefulness, and practicality; instead, from Walt Disney to Ted Turner and George Lucas, the focus shifted to sheer entertainment, delivered on a cutting-edge mass scale. In this fashion, The Last Tycoon is as prescient as much it is a clear relic from a long-gone era.

Fitzgerald’s depiction of a film industry that grew exponentially at the expense of a Depression-crippled populace similarly contains parallels to the contemporary United States and the aftermath of the “Great Recession.” As Congress calls for tax breaks for the upper classes and less regulation, while simultaneously ignoring wage equity and the persistence of poverty, the Hollywood-centric The Last Tycoon appears surprisingly universal in its scope. Along with The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald’s unfinished final work remains a prime portrait of the pervasiveness of American greed.

Post-Script- West and Fitzgerald: Oddly Intertwined Fates

As previously stated, West and Fitzgerald were not only fellow struggling novelists and freelance screenwriters, but close companions. The 1930s were not kind to either literary genius, and their top-tier Hollywood novels were ignored until years after their respective deaths. It is the eerie, surreal nature of both writers’ deaths that connect the two far more than mutual thematic concerns and a sincere friendship. On December 21st, 1940, Fitzgerald succumbed to his hard-living lifestyle and died of a heart attack in (naturally) Los Angeles, at the mere age of 44. Hours later, while in traffic in the small California hamlet of El Centro, West and his wife died in a sudden car crash. Legend has it that the catalyst for the accident was Fitzgerald’s death itself; allegedly, West had just heard of his comrade’s death and ran the red light in shock. No matter what happened that warm, sunny winter day, it is clear that these two writers would forever be inexorably linked.

Both Day of The Locust and The Last Tycoon bear the trademarks of their creators, including the “flaws” that each novelist’s detractors love to tear apart. Critics charged that West dealt with broad satire and grotesque caricatures, but the authentic surrealism and aching, deeply felt characterizations found in his most famous work firmly refute this view. Fitzgerald was criticized for keeping his steady, penetrating gaze on the upper classes in lieu of the numerous other segments of modern society. Readers of his unfinished final opus will find much to back up this claim, but the ultimate aim of Fitzgerald’s work was not to bask in the glow of the most prosperous, but to delve into their lives to skewer the wealth-obsessed culture of the United States.

At the height of the Great Depression, most Americans preferred the warm-hearted, earnest prose of Steinbeck over the idiosyncratic works of Fitzgerald and West. Hollywood represented a glorious ideal during this barren era, making the thought of a novel tearing apart this West Coast shangri-la seem nearly blasphemeous. Time has been kind to both novelists, and in the 21st Century, Steinbeck’s humorless, quaint portrait of the Depression appears to lack the gritty realism and vicious satire of Day of The Locust or The Last Tycoon. Fitzgerald and West may have intended merely to report on their frustrating experiences as Hollywood screenwriters, yet, both works inadvertently sum up a dispiriting era in modern American history. Even if these were the only novels written about Hollywood or 1930s socio-economics, the literary richness of these vital fictions would affirm these themes as among the most essential in American literature.

References

Adams, J. Donald. “F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Last Novel.” The New York Times, 1941.

Gordinier, Jeff. “Nathanael West and F. Scott Fitzgerald.” Entertainment Weekly, 1994.

Martin, Jay. “Nathanael West: The Art of His Life,” 1970.

Price, Patrick “The Impact of Hollywood During The Depression.” NSSC.org, 2013.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Good, thorough analysis. I always find modern, post-WWI, pre-WWII lit to be fascinating. Lots of disillusionment going around, and Hollywood would certainly represent a lot of the excess authors like Fitzgerald criticized.

I read Day of the Locust recently for the first time after previously reading two books by Horace McCoy, who also wrote of 1930s Hollywood, but I found myself liking the books of Horace McCoy much more, even though they too, are sad and depict the underside of the Hollywood dream.

Fitzgerald is very hooked on dramatizing love.

It would be nice to see how Fitzgerald would have ended it.

West’s voice is unique to most other writers I’ve experienced because there isn’t an ounce of hope in his writing!

Hollywood offered an illusion, an escape from a world that many writers perceived to be increasingly dehumanized. WWI on a symbolic level showed the very worst that the 20th century had to offer. That recognition that whatever inkling of a utopian vision that may have existed at the very beginning of the 1900s vanished, leaving behind an all-too-real and unmagical reality of the destructiveness of the human heart. It’s so interesting that both writers had this incredibly complex relationship with Hollywood and all it had to offer.

West is quite explicit in his cultural analysis and I really like that.

These works are highly respected in literary circles.

Only in California! Only in Hollywood!

Anything by Fitzgerald is better than West’s work.

Lovely article. I chose to re-read The Love of the Last Tycoon after reading What Makes Sammy Run, just to get another fix of inter-war Hollywood novels (I’ll re-read Day of the Locust eventually, too, and probably also the tremendously underrated I Wake Up Screaming).

Fitzgerald has a way to draw you in with his ability to write about a sort of forbidden romance.

For someone with admittedly little knowledge of pre-WWII American literature, this article was fascinating and well-timed. These novels parallel economic disparities and a seemingly community-wide disillusionment occurring in America today. The author did an excellent job emphasizing the novels’ beauty and literary merit as well as their modern social relevance. Especially in light of recent political campaigning, my lack of patriotism has left a void and fear in me that may be quelled by similar feelings in artistic geniuses some eighty years ago.

I’ve been craving period Hollywood stories, thank you!

I’m very fascinated with Old Hollywood, particularly 1930s Hollywood. I love to read books that where written back then, about Hollywood dreamers who never got anywhere with their dreams.

Fitz was truly a master at character building and intrigue.

I’m a great Fitzgerald fan. I’ve read and liked most of what he wrote.

I was not too fond of his first novel, This Side of Paradise. It came across as vain with a self-serving protagonists. Of course The Great Gatsby is far superior in its use of characterisation ans story telling.

Fitzgerald is one of my favorite authors, but I can’t say that I actually enjoyed The Last Tycoon all that much. I know that he is typically dry, but this book just seemed uninteresting to me.

I definitely prefer Fitzgerald short stories to his longer works.

Books are full of symbolism.

Dear Fitz, Why did you have to abuse yourself so much and die before you finished your last book?!

West created a great nightmare kind of vision of Hollywood during the depression.

Fitzgerald has a very distinct style of writing and there something truly apocalyptic about Nathanael West’s stories.

Most impressive in West’s book is its self-awareness.

Fitzgerald’s temple of mind is admirable.

That’s really eerie how they both died that close to each other in time.

“The Last Tycoon” contains some of the most beautiful prose Fitzgerald ever put down on paper. Just because the novel was unfinished is not a reason to never pick it up. Star is a complex protagonist whose presence carves out an uncommon perspective on the Hollywood scene in the 30’s. I distinctly remember a few scenes (won’t spoil them in this comment) where Fitzgerald paints him in such a light that parallels the profound sincerity that Gatsby expresses. I hope a few potential readers are convinced to pick up the novel after reading your article.

I had only heard of West before reading this, but you’ve definitely interested me in his four novellas.

This was a very good read!

Fascinating article! I am just starting to read read Fitzgerald’s works for the first time and now I think I’ll have to pair them with West. It’s interesting to read about these amazing writers that sit on such high pedestals now having to stoop low (or I should say west) to make a living. I’m really interested in the lives they lead in Hollywood. This was a great read.

A good essay, enjoyable to read.

Interesting. I am more familiar with Fitzgerald and Steinbeck than West.