Maternal Horror Films: Understanding the ‘Dysfunctional’ Mother

We all assume that mothers are associated with nurture, care, love and protection. Yet why are we so fascinated with threatening mothers who do not fulfil those expectations? Those fantasies around the ‘Bad Mother’ are often present in the horror genre – the theme is so popular that it has become a sub-genre, the maternal horror film. Mothers in maternal horror question the status of motherhood as they become the source of danger in the film, and fail to protect the child.

In maternal horror films, mothers are represented as violent and threatening figures. They are depicted as potential dangers for their children and distinguish themselves from the traditional maternal model. The Babadook (Jennifer Kent, Australia/Canada, 2014), Dark Water (Hideo Nakata, Japan, 2002) and The Others (Alejandro Amenábar, Spain/US, 2001) are three very interesting films to explore in relation to their depictions of dysfunctional mothers. Those mothers are pushed to harm or abandon their children, and challenge classical representations of motherhood. The films flesh out the elements that push those mothers to turn into destructive and dysfunctional forces. These elements include the pressures and expectations that social structures place on motherhood; the absence of the father and the belief that the dysfunctional mother threatens patriarchy; and the repression of the mother through the abjection of her body and her confinement within a domestic space, often haunted by a dark past.

I. Defining the ‘Dysfunctional’ Mother

The mother figure in maternal horror films defies the expectations around her role – she is either unable to protect the child’s safety or on the verge of destroying what she has brought to life. She switches from a life-giving to a death-giving entity, and becomes ‘other’, monstrous and ‘dysfunctional’. The term dysfunctional is defined as ‘not operating normally’ and ‘unable to deal adequately with normal social relations’. In maternal horror films, the mother is assumed dysfunctional because she does not ‘operate’ in a protective way and fails to build a ‘normal’ relation with the child. She also struggles to build social relations with other members of society due to her excessive mistrust of others. She turns paranoid, unreasonably or obsessively anxious, mistrustful and suspicious.

By mistrusting everyone, the mother socially alienates herself and her offspring and refuses support from other social circles. Her paranoid mind is flayed open on screen, and the films become psychological studies of the mother’s dysfunctional state. For Brenda Foley, the films ‘explore the tortured landscape of the mind’ 1, opening up a mother’s troubled soul and mental fragility for all to see. This is particularly appealing for viewers as they see a mother, symbol of stability, become unpredictable and distraught. As Jeffrey Bullins writes, ‘audiences have a fascination with mentally unstable characters’ 2. The pleasure of the film therefore comes from witnessing the mother’s descent into madness as she becomes the object of terror.

In The Babadook and The Others, the audience is presented with two dysfunctional mothers, Amelia (Essie Davis) and Grace (Nicole Kidman). They are dysfunctional as they kill or attempt to kill their children, controlled by their destructive impulses. They live alone with their children, with no friends or family – their social isolation entraps them within a damaging mother-child dynamic which pushes the mothers towards mental instability. In The Babadook, Amelia locks the door of the house and cuts off the phone to prevent Samuel (Noah Wiseman) from contacting anyone. She isolates both of them and makes sure ‘nothing gets in’, leaving Samuel at the mercy of his mother’s murderous impulses.

In The Others, Grace locks herself and her children in the house and becomes suspicious of any intruders, like her new servants. She even shuts the windows to prevent the intrusion of sunlight, confining her children to perpetual darkness. In both examples, the mothers’ fear of intrusion makes them unable to deal adequately with social relations. By isolating themselves with their children, Amelia and Grace feed their neurosis and their dangerous potential – they fail to protect their children and violate what society codifies mothers to be.

II. The Fear of not Meeting Expectations Around Motherhood

In maternal horror films, the fear of not fulfilling motherhood’s expectations is the first element that builds anxiety within a mother and increases her chances of becoming dysfunctional. Being a mother comes with societal pressures – as she takes upon herself the responsibility of child care, she also agrees to train the child to society’s rules. ‘Social groups demand the mother raises the child in an acceptable manner, [ensuring] preservation, growth and social acceptability’ 3 says Sarah Ruddick. The child depends on adults for his well-being, therefore the mother – his primary caretaker – has to protect him and prepare him for societal life.

The mother considers herself and is considered by others to be responsible for maintaining her child’s growth, and lives with the fear of generating a defective development. If her child does not thrive, society blames her, bombarding with guilt. By idealising the figure of the Good Mother, society creates a fear of the Bad Mother, a title a mother will place on herself if her child develops an abnormal behaviour. This constant pressure can lead a mother to become increasingly anxious and depressed, which increases her chances of failing at her role.

Children of depressed mothers tend to show more ‘behavioural disturbance, […] insecure attachment, more difficult temperament and greater risk for developing depression when older’, writes David Foreman 4. This is demonstrated in Samuel’s behaviour in The Babadook. He builds harmful weapons to protect himself from ‘monsters’, showing a tendency towards violence and a difficult temperament whenever Amelia tries to confiscate his weapons.

In social situations, Samuel is awkward, isolating himself or clutching his mother desperately. He even pushes his cousin from the top of a tree house and shouts hysterically in the car on the way back. Samuel’s behaviour shows disturbance, insecurity and an unhealthy attachment to the mother. His growth has potentially been impaired by the loss of his father, but most importantly by his relation with Amelia, who has to cope with the pressures of motherhood and raise a child with a difficult temper on her own. The Babadook therefore shows the impact of an overly-stressed mother on her child, predisposing Samuel to behavioural instability.

Society puts particular pressure on single mothers as they become the only caretaker for the child. In the three films, Amelia, Yoshimi (Hitomi Kuroki) and Grace struggle to raise their children alone. Yoshimi and Amelia have to balance between work and home. By having to also provide financially for the family, the mother becomes totally engrossed in her caretaker role – the child becomes the exclusive reason behind all of the mother’s actions and this can become stifling for the mother. A working mother is also perceived negatively by society according to Kathleen Rowe: ‘To be a mother is not an easy task in a culture where mothers can be blamed […] for being too present or not present enough, for leaving their homes to work.’ 5. So if a mother needs to assume the breadwinner role, usually regarded as a male activity, she is judged for it and alienated from social circles, creating extra pressure on her.

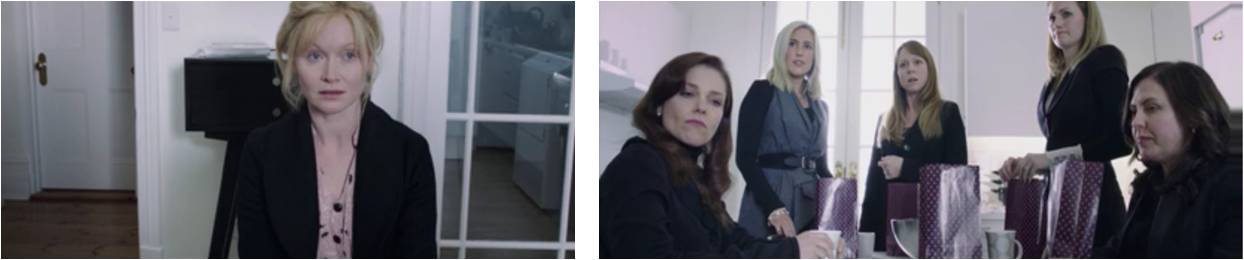

This is shown in a particular scene of The Babadook, at Amelia’s niece’s birthday party. Amelia is estranged when she talks to other mothers, constantly reminded of the expectations that weigh over her head. She is singled out as a working, widowed mother. Samuel refuses to leave his mother and play with other children, demonstrating ‘behavioural disturbance’ and an insecure attachment to Amelia. The other mothers roll their eyes in exasperation when he leaves the room, as if they were judging Amelia’s mothering methods.

After discussing Amelia’s career situation, one woman talks about how hard it is for her to see ‘disadvantaged women’ who lost their husband deal with everyday life, labelling Amelia as a ‘disadvantaged’ mother, an outcast of social norms. This triggers Amelia’s anger – when the woman complains about the fact she has no more time to go to the gym, Amelia snaps at her, emphasising how insignificant her problem is compared to Amelia’s daily worries. The camera isolates Amelia throughout the conversation, juggling between a close-up of her tired face and a reverse shot of the mothers, sitting together in the frame, opposite Amelia. Amelia is therefore singled out and scrutinized by society, unable to fit the ‘standard’ image of motherhood.

The single mother is constantly evaluated by friends, neighbours but also by officials. Amelia is visited by social assistants that keep questioning her relationship with Samuel, and Yoshimi in Dark Water is regularly interrogated during her battle over Ikuko’s (Rio Kanno) custody. Constantly judged by the social world, the mother’s stress increases and impacts her mental health. After insensitive questions about her past consultations with a psychologist, and after her ex-husband exaggerated an incident about picking up Ikuko after school, Yoshimi attacks her ex-husband in front of officials, screaming hysterically. The pressure of being observed and judged by an oppressive patriarchal society, represented through the ex-husband and the male officials interrogating her, pushes Yoshimi to act irrationally. She lets her internal anger manifest through physical violence and hysterical behaviour. This shows that the expectations placed on the status of mothers can be too hard for women to handle and can drive them to become dysfunctional and impulsive.

These impulsive behaviours turn the mother against her children in classic maternal horror films. The mother becomes violent, inadequate and mentally unstable around her children, unable to cope with the pressures of motherhood. This is shown differently in The Babadook and The Others: while Amelia shows a lack of affection and tolerance towards Samuel in certain scenes, Grace over-performs her role of mother in an obsessive way. Amelia tells Samuel to ‘eat shit’, refuses to provide food for him and even tells him that many times she had wished Samuel had died instead of her husband, completely rejecting her mothering role. She rejects the idea that motherhood should be a ‘totalizing experience of consuming self-sacrifice’ 6 as put forward by Nina Martin. She is tired of being told that the child should be a mother’s entire world, creating a romanticised relationship around motherhood that Amelia does not fit.

In contrast, Grace performs her role to such an extreme that she does not allow her children to leave the house and protects them from the sunlight. She says she would rather die herself than let anyone harm her children, defining herself purely through her mothering role. Her obsession turns into delusions as she imagines Anne possessed by a monstrous figure. Unable to recognise her child, she attacks the monster screaming hysterically ‘you are not my daughter!’ until she finally realises it is actually Anne. Her dedication to her children and her fear of potential intruders (supernatural or human) drives her to hallucinate and physically harm her children (even kill them as we learn in the end). Hence her fear of becoming a Bad Mother turns her into a danger as she conforms fanatically to the mothering role. In both cases, the mother’s relationship to the children becomes strangulating. The totalising experience of motherhood praised by patriarchal society becomes the source of the mother’s violence. With the absence of the father, the mother is enslaved within her parental role and has to accept the totalizing experience of motherhood, which leads her to resent her child therefore become dysfunctional.

III. The Absence of the Father Figure

In maternal horror films, the mother often abandons or is abandoned by the father, another element that contributes to the mother becoming dysfunctional. Societal beliefs put more pressure on single mothers as they take the lead and the patriarchal figure is removed (whether by death or by divorce). By assuming both the paternal and maternal role, the mother’s presence becomes total, and the child only has the mother to learn from. This is perceived as a threat to masculine authority and emphasises the paranoia around motherhood. Patriarchal society believes that the dysfunctional mother endangers the child’s social development by clinging on to him and refusing to cut the mother-child bond.

Feeling abandoned by the father and by society, the dysfunctional mother starts to define herself solely through the child, refusing to let him go therefore resisting conformity and becoming a ‘transgressive figure’ 7. From a psychoanalytical viewpoint, the patriarchal imaginary believes that the dysfunctional mother prevents the child’s access to patriarchal society – she isolates herself with the child or chooses to kill him in order for him to remain with her eternally, therefore challenge the patriarchal order.

In psychoanalysis, it is believed that to become socialised and reach the ‘Symbolic order’, the child, especially the boy, has to break from the ‘primary identification with the mother’ 8 and eradicate his association with the feminine, writes Christine Glendhill. ‘The Symbolic Order’ is a term introduced by Jaques Lacan which stands for the social world of linguistic communication, inter-subjective relations, acceptance of the law and knowledge of ideological conventions. Once a child has entered language and understands societal laws, he is able evolve in the social world.

The Symbolic Order is believed to be the realm of the masculine, and the pre-Symbolic order the realm of the feminine. The pre-Symbolic is a temporary phase that the child needs to break from to become socialised, and the father figure stands as a model for the child/boy to follow. But if the father is absent, the child becomes attached to the feminine and resists the separation with the mother. In the absence of the father, the dysfunctional mother nurtures this attachment therefore prevents the passage to the Symbolic Order and threatens the stability of the patriarchal world.

These psychoanalytic readings can be applied to the films as they portray the children’s difficulties to become part of the social world, stifled by their relationship with the mothers. As we saw with Samuel, his over-attachment to Amelia prevents him from socialising with other children. He is afraid of social situations and keeps coming back to his mother’s arms, unable to detach himself from the realm of the maternal, from the umbilical cord. Even when Amelia is violent towards him, he keeps telling her he will not leave her. Without the presence of the father, and with Amelia assuming every role in the family sphere, Samuel attaches himself to Amelia in an unhealthy way and refuses to enter the social world.

Samuel is even scared of monsters and intrusions, physically protecting himself from strangers. Tammy Oler 9 points out that Samuel actually starts building weapons even before the Babadook appears in their home, as if he senses that the monster will soon creep in and that his isolated relationship with Amelia is unhealthy. Or are these weapons meant to protect Samuel from social relations in general? Are they a sign of his rejection of the Social Order, a result of his ‘disrupted’ and exclusively feminine growth?

Nicholas in The Others develops a similar behaviour. Although he does not build weapons like Samuel, he fears social relations and intruders. He is always in his mother’s arms, drawn to her whenever he is scared. Nicholas shows an extreme attachment to Grace, an attachment she has nurtured by preventing her children from going outside or socialising with other people. She is the only presence in their lives as the father has left for war. The maternal takes control and because Grace defines herself exclusively through her children, she never lets them go. This is something Anne abhors – as she is older than her brother, she enters a transition period where she wants to leave the realm of the mother to encounter the social world, but Grace prevents her from doing so. She even becomes aggressive towards Anne, pushing Anne to hate her mother. The children’s extreme behaviours are a product of the absence of the father and the mother’s over-attachment to the children in response – her possessiveness becomes a sign of her dysfunctional nature.

The idea of a mother’s potential to turn dysfunctional and possessive if the father disappears adds extra pressure on motherhood and feeds the paranoia around the Bad Mother. Luce Irigaray argues that the projection of male imaginary has made women suffer culturally as they were imagined as ‘devouring monsters threatening madness and death’ 10. The maternal horror film is an example of these projections – as Steffan Hantke argues, male anxieties about female empowerment and men’s declining social status have given rise to films where women are the avenging ‘demonic other’ 11. Representing women, and especially mothers, as demonic and monstrous nourishes the paranoia around femininity and socially alienates women. The masculine fear shifts as women start doubting themselves and believing the patriarchal discourses. Mothers have to live with the pressure of being constantly perceived as unpredictable, fearing their potential ‘monstrous’ nature, which affects their mental stability and the way they identify themselves.

This idea is explored in a lot of details in The Babadook. The figure of the Babadook can be understood as Amelia’s frustration at her life, her growing depression and her difficulty to get over the loss of her husband. The babadook appears at the moment Amelia shows doubts about her desire to be a mother – it is a projection of her tortured mind. Using Amelia’s weakness, the monster attempts to take control of the mother and her son. The fact that the monster has masculine traits, and that it even turns into Amelia’s dead husband at some point, shows that the source of Amelia’s distress is linked to the patriarchal order and the loss of the male authority within the family. The monster is there to put pressure on Amelia and turn her into a dysfunctional mother.

When the Babadook takes the shape of the deceased husband, he asks Amelia to ‘bring him the boy’, a way to recall the child into the masculine realm and terminate the engrossing relationship with the mother. Amelia’s frustration makes her vulnerable, and in some way she accepts the monster’s offer as she ‘lets it in’, believing that by killing her child, she can gain peace of mind and no longer be solely seen as a caretaker (through her duty as a mother and as a nurse). Gradually, she becomes the monster. Her transformation starts with a tooth pain, then a variation in her language which becomes more aggressive. She then takes on the low and terrifying voice of the monster and becomes more animalistic, climbing on the walls of Samuel’s room, about to catch her prey. By becoming the monster, she enacts the patriarchal fantasies surrounding motherhood and embodies the paranoia around the monstrous/dysfunctional mother.

When she transforms into the monster, Amelia gives way to her pain and resentment, and ceases to repress her feelings about her dead husband. She admits to Samuel that since the death of his father, she ‘hasn’t been good’, calling herself ‘sick’. She asks for help and says she wants Samuel to meet his father, in ‘that beautiful place there’. At this point, we do not know if it is the Babadook talking through Amelia or Amelia sharing her sincere feelings – either way, the pain of her husband abandoning her leads Amelia to have murderous feelings towards her son. But if she kills Samuel, she fails in her mission of preparing the child for the Symbolic World.

The Babadook is therefore a construct that encourages Amelia to become dysfunctional, a reflection of Amelia’s depression and exhaustion. It pushes her to act irrationally and kill her child, like Grace in The Others. Unable to cope with the absence of her husband and the constant confinement within the house, Grace killed her children and herself, letting her fear of remaining abandoned and becoming a ‘monstrous’ mother win over. Grace has let her own Babadook take control of her. The absent fathers in maternal horror films therefore generate fear within the mother as she apprehends taking care of the child alone and becoming dysfunctional. Male authority is therefore at the heart of the neurosis around bad motherhood.

It is interesting to take Dark Water as a different point of comparison. The patriarchal abandonment is of a different kind as this time it is wanted by the mother. She chooses to leave the husband and the masculine realm by divorcing, and throughout the film she is punished for it. Yoshimi suffers extreme stress because she is confronted to the practical demands placed on her as she chooses to slip out of male control. ‘Yoshimi’s problems appear ignited by the breakdown of her marriage and the lack of resources available to her in a male-oriented society’, writes Barbara Creed 12. Yoshimi lives under the pressure of finding a job, proving to social assistants that she can take care of her daughter while being a single mother, and fixing her collapsing apartment.

She is surrounded by male figures that fail to help her – when she talks about the strange events happening in her building, the male figures (her ex-husband, his lawyers, Ikuko’s teacher, the building’s concierge…) doubt her and believe she is mentally unstable. Her ex-husband depicts Yoshimi as mentally vulnerable in order to gain the daughter’s custody, using fragile moments from Yoshimi’s past as a wedge to pry away Ikuko from the mother’s grasp and engulf Yoshimi in self-doubt. The husband builds a paranoid image of Yoshimi to gain the child back and allow the passage to the Social Order, punishing Yoshimi for her transgressive behaviour. Yoshimi’s contribution to the family is only recognised when she gives up the daughter at the end of the film, leaving the child to the paternal function. The father must therefore repress the mother and construct her as a dangerous and delirious entity to maintain patriarchal rule. Repression becomes a tool to restrict the mother, but the oppression becomes too much and actually pushes the mother to become dysfunctional.

IV. The Paranoia around Maternal Sexuality: Repressing the Mother’s Body

Repression is another important element to consider when exploring the reasons for a mother to turn dysfunctional. By confining a woman to the mother role, patriarchal society does not perceive her beyond her reproductive function which suppresses the rest of her identity. Women cannot be working, or acknowledge their desires – their cravings and ambitions must be repressed. This is done through the abjection of the mother’s body and her confinement within the domestic space. By suppressing the mother’s desire and entrapping her within a closed space with the child, the male authority remains in control. But repression and confinement can push the mother towards mental instability as her freedom and sense of self are suppressed. She can therefore become dysfunctional and fall into hysteria, the ‘bodily expression of her unspeakable distress’ 13. The mother’s desire becomes a symptom and its repression leads to mental and physical illness, making the female body even more inaccessible to male control.

The mother’s body is at the heart of the paranoia around motherhood and dysfunctional mothers as it is perceived as mysterious and abject. Because the mother’s body is incomprehensible to the masculine, it becomes a source of terror. For Julia Kristeva, the image of the woman’s body, because of its maternal functions, is more likely to signify the abject 14. Images of menstrual blood, vomit and other ‘unclean’ elements are associated with the mother’s body and are also central to our culturally constructed notions of the horrific. Therefore the maternal body is associated with the horrific, revealing a real societal neurosis around motherhood and female sexuality.

The monstrous mother incarnates this neurosis – she embodies the phallic woman or symbolic castrator according to Freudian readings. She resists the masculine realm by obstructing the child’s access to the Symbolic World, thus suppressing the power patriarchy has over the child. With a dysfunctional mother and an absent father, the child remains within the primal bond, a phase called ‘abject’ because it precedes the Social Order and exclusively belongs to the maternal. If the child stays in this phase, he develops an insecure bond with the mother and is unable to break away from his incestuous desire for the mother, from the ‘bodily encounter’ 15, therefore access the social world. The dysfunctional mother therefore breaks free from the patriarchal hold by preserving the primal bond with the child and suppressing the masculine voice.

Each of the three films depicts the repression of the mother’s body and the consequent attachment with the child. In The Babadook, Amelia is presented as a sexual being constantly repressed because of her mothering duty. Each time she tries to experience pleasure, she is interrupted by Samuel. In a very intimate scene, Amelia masturbates in bed and Samuel creeps in her room. Later, Samuel interrupts a conversation between Amelia and the visiting Robbie (Daniel Henshall), foiling all of Amelia’s attempts at sexual satisfaction. These interruptions illustrate the daily repression imposed on the mother’s desire, and they add to Amelia’s frustration. Instead of finding pleasure, she has to deal with Samuel’s stifling presence, tying himself into a quasi-conjugal relationship with his mother, a sign of his own desire for her. In the absence of his father, Samuel becomes the repressor. Amelia’s sexuality is therefore constantly repressed since the death of her husband, and from this repression springs terror and violence that turns Amelia into a ‘monstrous’, dysfunctional mother.

In The Others, Grace’s madness can also be partly explained through the constant repression of her sexual desire. With the absent father, Grace has to repress her sexual needs and dedicate herself to the children. Grace is also depicted as a sexual being, especially with Nicole Kidman playing the role. Kidman carries with her a glamorous Hollywood image that the film uses to portray Grace’s attractiveness. This is especially conveyed in the sex scene with the husband, when Grace strips in front of the camera and reveals a light nightgown and some garters. Kidman’s body brings desirability to the character and presents Grace as a sensual being. When the husband tells Grace he is leaving, a sign that Grace will have to repress her desires again and dedicate herself to the children instead, she throws herself on the bed crying. The fragility of her body and her emotional state invites the father to kiss her and they end up having sex. When she wakes up, he is gone, leaving her confined within the house and having to deal with her repressed needs. The father therefore controls the mother’s sexuality and chooses when to repress and when to unleash it, driving Grace mad. Her repressed sexuality therefore leads her to become dysfunctional – we understand that she has killed her children because she could not stand the confinement and sexual repression she was subject to.

In Dark Water, the motif of flooding water relates to the notion of the ‘abject’ and acts as the repressor within the film. It invades Yoshimi’s apartment and prevents her from building a safe space for Ikuko, repressing the mother-daughter relationship. We learn that the leaks are provoked by Mitsuko (Mirei Oguchi), the ghost child. Through those leaks, Mitsuko tries to summon a mother figure to her side. Water recalls the primal phase, when the child is still in the mother’s womb – it is therefore a symbol for the return to the bodily encounter with the mother. Mitsuko wants to return to the safety of the primal phase, therefore attempts to kill Ikuko to win Yoshimi and turn her into Mitsuko’s surrogate mother.

Yoshimi fights the water, but she has to give up in the end, abandoning her daughter along the way. The inky blackness of the water slowly takes control of the mother and the house, bounding her to the domestic space and the primal encounter with the child. Yoshimi is therefore repressed and forced to abandon her own child in order to pay the consequences of Mitsuko’s dysfunctional mother – in a very paradoxical way, she has to become dysfunctional too to protect Ikuko. She has to accept the recall to the primal phase but with another child, which will imprison her within the house and an unforgettable past, and drive her away from her own daughter.

V. The Threatening and Repressive Domestic Space, Symbolic of a Haunting Past

Repression of the mother also occurs within the domestic space as the mother status is intrinsically linked to the home. Patriarchal society confines the mother within the house in order to contain her. The home is established as the ‘headquarters for a mother’s organizing and a child’s growing. Home is where the children are supposed to return when their world turns heartless’, says Sarah Ruddick 16. Yet in maternal horror films, it is the home that turns heartless and where the horror takes places – the domestic space becomes dysfunctional.

The confinement within the house pushes the mother towards dementia and as the child is confined with the dysfunctional mother, he is placed a dangerous position. According to Sarah Arnold, the child is trapped in the claustrophobic domestic sphere of the mother therefore forced to ‘re-embrace the maternal bond and return to the pre-Symbolic order’ 17. The house is therefore at the heart of the mother’s neurotic violence towards the child as she wants to keep him within the ‘abject’ phase’. It becomes a space of paranoia and challenges the classic representation of the familial sphere.

In the three films, the mothers become hysterical as they are swallowed up by the menacing home. The danger comes from the house slowly decaying and having a will of its own, out of the mothers’ control. In The Others, the curtains that protect the children disappear, and in The Babadook, a hole starts to form in the wall, letting insects crawl into the house. In the face of their failure to protect the domestic space, the mothers lose sanity and struggle to resist the oppression of their home. The houses are filmed in a very stifling way, the camera lingering on objects of the past and slowly panning across empty rooms which highlights their oppressiveness. Rooms are suffused in shadow, filled with dark corners that lock the characters within haunting memories of a past family unity, when the husband was still present. The house becomes a symbol of a past they cannot overcome. Stuck in grief and obliged to still perform the maternal duties, the mothers lose control and become as oppressive and dangerous as the house they live in.

In Dark Water, the building where Yoshimi and Ikuko live reflects a past that comes back to haunt the new tenants, asking for the repairmen of past mistakes. The building is presented as frightening, towering over the small figures of Yoshimi and her daughter in aerial shots. The two characters are isolated and dwarfed by the imposing structure, foreshadowing how the building will entrap and dominate Yoshimi and Ikuko. The grey walls and endless hallways mirror the bleakness of Yoshimi’s new life as she now has to find employment while fighting a bitter custody battle with her ex-husband. The deterioration of the flat parallels the deterioration of Yoshimi’s mental state as she struggles to cope with everything, acting hysterically as she tries to identify the source of the leaks in her ceiling. The broken elevators, cracking wallpaper and invading water suggest that the pressures placed on Yoshimi are about to swallow her, and the home becomes a dreading and unsafe place that cannot be escaped.

The invading water refers to Mitsuko’s incident and is controlled by the girl as she summons Yoshimi to become her replacement mother. The film suggests that Mitsuko’s mother’s inadequate care is to blame for the girl’s death, therefore Yoshimi has to repair the deed. She cannot resist Mitsuko’s intrusion in her life as the ghost is part of the building, the domestic space. To appease the ghost, Yoshimi has to abandon her daughter. By accepting to become part of the house and Mitsuko’s surrogate mother, Yoshimi bridges the tension between past and present families, returning to a more traditional mother role where she is confined within the domestic space and does not try to handle employment and divorce.

The past comes back vengeful and actively forces its way into modern life to demand a return to the traditional. The mother is punished for wanting to break away from the constraints of the house and of the maternal model constructed by patriarchal society. This suggests a cultural nostalgia for the past and a societal fear of moving forward – society struggles to construct a new motherhood model and to believe that a mother who is allowed an identity outside the maternal realm, and a sexuality of her own, is not necessarily dysfunctional.

Maternal horror films allow the audience to understand better the societal paranoia around motherhood. An essential entity, the mother represents stability, and her potential to become unstable is feared as it will damage the children, future members of society. The mother is therefore oppressed by societal expectations and suffers from the patriarchal representation of motherhood. The repression of her body, her status and her sexuality become elements of confinement that in the films, push her to become dysfunctional and horrific. But the maternal horror film also shows love among the terror and often ends with the formation of a more healthy relationship between the mother and the child – can dysfunctional mothers redeem? Or is this a way to present mothers in a more positive light and silence the paranoia?

Works Cited

- Brenda Foley, ‘The Maternal Madness of the Babadook’, Cinapse (8 December 2014) <http://cinapse.co/2014/12/08/the-maternal-madness-of-the-babadook/> ↩

- Jeffrey Bullins, Evil or Misunderstood: Depictions of Mental Illness in Horror Films, Academia.edu, <http://www.academia.edu/9388210/Evil_or_Misunderstood_Depictions_of_Mental_Illness_in_Horror_Films> ↩

- Sara Ruddick, Maternal thinking: Towards a Politics of Peace (Boston: Beacon Press, 1989), p.17 ↩

- David Foreman, ‘Maternal mental illness and mother-child relations’, Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 4 (1998), p. 136, http://apt.rcpsych.org/content/aptrcpsych/4/3/135.full.pdf ↩

- Kathleen Rowe Karlyn, Unruly Girls, Unrepentant Mothers (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011), p.111-2 ↩

- Nina K. Martin, ‘Dread of mothering: plumbing the depths of Dark Water’, Jump Cut, 50 (Spring 2008) <http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc50.2008/darkWater/index.html> ↩

- Sarah Arnold, ‘Bad Mother’, Maternal Horror Film (University College Falmouth: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), p.69 ↩

- Christine Glendhill, Home is Where the Heart Is (London: British Film Institute, 1987), p. 307 ↩

- Tammy Oler, ‘The Mommy Trap’, Slate (24th November 2014), <http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2014/11/horror_movies_about_mothers_and_children_the_babadook_lyle_and_other_films.html> ↩

- Luce Irrigary and Margaret Whitford, The Irigaray Reader (Cambridge, Mass.: Basil Blackwell, 1991) ↩

- Hantke, Steffan, ‘Japanese Horror under Western Eyes: Social Class and Global Culture in Miike Takeshi’s Audition,’ Japanese Horror Cinema, quoted in Sarah Arnold, Maternal Horror Film, p. 124 ↩

- Barbara Creed, Phallic Panic (Carlton, Vic., Australia: Melbourne University Press, 2005) ↩

- Janisse Kier-La, House Of Psychotic Women (Godalming, UK: Fab Press, 2012), p. 149 ↩

- Referred to in Barbara Creed, Phallic Panic. ↩

- Luce Irrigary and Margaret Whitford, The Irigaray Reader ↩

- Sara Ruddick, Maternal thinking, p. 87 ↩

- Sarah Arnold, ‘Bad Mother’, Maternal Horror Film, p. 93 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The Others was a phenomonally scary film. Getting to the twist and then realising it is what made that film imo.

The Babadook was one of the greatest films I’ve ever seen about the truly debilitating effect of grief, right up there with Todd Field’s In the Bedroom and Haneke’s Amour.

I’d have never thought about Babadook quite like that but yes I’d have to agree with you 100%. Thank you for that illuminating insight. And I’ve never cried so much watching a film as I did watching Amour. Literally floods of tears and grief stricken for days.

These films allows us to empathise with a person’s struggle against things beyond easy comprehension (one way of thinking about fear) and this is where its strength lies.

For me personally, horror has to have some element of the supernatural in it for it to be scary. The Japanese ones are the scariest imo; the only Hollywood movie I have ever found scary was panned by critics (probably because of the convoluted plot; dolls, vengeful spirit, puppets, it had everything for maximum effect).

Supernatural horrors are the best. I had been binge-watching some movies and tv shows based on the supernatural the past few days and I had a nightmare just a couple of days ago that I myself was in one of these settings. In it, I had gone out for dinner with some friends. Strange things began to occur at the restaurant and people started disappearing one by one. There were murmurs of something sinister. For some reason (it was a nightmare, details are sketchy), people were unable to leave the place and were waiting for sunrise. I told my friends there was something strange about one of the waiters and I told them I tried see his reflection quite a few times. I told one of my friend there might be something suspicious about the waiter. Just then, I heard a cackling sound from another one of my ‘friend’s behind me asking, “Is that so??”. I didn’t dare look at ‘him’.

Thankfully, I woke up.

Nice analysis, I’ll have to check all of these out.

This is a wonderful article. The Others is one of my favorite films of all time, and The Babadook is a great movie. I think this point really clenches it: “By becoming the monster, she [the maternal figure] enacts the patriarchal fantasies surrounding motherhood and embodies the paranoia around the monstrous/dysfunctional mother.” That’s it. It’s along the same lines of seeing many horror movies where pregnancy is depicted as traumatic, alien, or even monstrous (demonic products of rape, literally giving birth to the Antichrist and the mother being controlled or stalked by other people, and so on).

Both The Others and The Babadook have an absent father and the deterioration of a single mother, which is definitely damning for her agency and power. The families are shown as deeply imbalanced without a patriarch. It was also great to point out the sexual repression due to Sam interrupting Amelia when she’s shown masturbating and Grace’s husband leaving after sex. While I love both these movies, the single mother-as-villain dynamic never quite sat right, and I think you hit the nail on the head as to why. But as you said, the movies also show the toll of grief, repression, and patriarchal standards where mothers are expected to be endlessly devoted to their children and have maternalism as their defining trait. The either-or divide between motherhood and the outside identity of being someone with sexual desire is incredibly toxic.

This is great material. Thank you for taking the time to write such a thought-provoking piece.

Thank you very much for all this nice feedback, and I am glad you enjoyed the article! The topic is fascinating and horror films have so much more to give if one takes the time to analyse them.

Scary movies are not my thing but I did enjoy reading this article and your analysis. Very deep and insightful.

Horror films are not my staple fare, as few movies are genuinely scary, with most descending into unimaginative blood spattered gorefests.

Have you watched The Orphanage? It is sold as a horror story but it is actually heart breakingly sad. I have only watched it once and will probably not watch it again because I almost cried the first time.

“Inside” almost made me not want to have another kids? The movie totally freaked me out.

That damned “Babadook” movie scared the hell out of me & im not ashamed to say it.

The terror of the Babadook lies in its allegorical depiction of degenerative and unchecked mental illness seen through a child’s eyes. So many people don’t seem to get that. The film was perfect. It took me days to shake off the unease.

I thought the child was more scary than the Babadook.

I had high hopes for when watching The Babadook but I was really disappointed. Right up to the end credits, I was waiting for something to happen, but it never did. It was just standard psychological horror fare really, (with good if slightly overwrought performances) but it thought it was much cleverer than it really was.

I really enjoyed The Babadook, and I agree with a lot of your analysis. Very interesting article. After reading it, I really want to check out those other two movies, too.

My only issue is with some of the Freudian psychology that you decided to use – I can see and understand the reason for it, and it did offer a good tool for analysis, I just don’t personally agree with Freud’s ideas, especially since they are inherently gendered. Especially in the case of The Babadook, if Sam was a girl, then that argument wouldn’t play out nearly as well as it did within your article, and from he sounds of the female child within The Others and Dark Water, it can’t really apply too well there, either. But, that is the limits of the Freudian approach, and it’s still interesting to see it applied.

Thanks for reading this article 🙂 I agree with you that Freudian theories are very limited, that is why I did not give any opinion on these theories. I am just aware that the Babadook as it is written, with a male child, can somehow ‘fit’ Freudian approaches, to an extent. I agree that it is more limited with the two others films, which is why I did not develop the Freudian approach on the other two, although the over attachment to the mother appears in all of the films. One would have to read Freud’s theory about the female child a little bit more I think.

This is a great point that I often thought about while studying Freud. It’s tough because, yes, Freudian theories are deeply problematic, but they are also a system in which culture has been created within for so long. I think that there is a bit of a self-fulfilling system regarding Freud, and arts and culture tend to keep the system going.

I love horror films but sadly 99.99% of them are rubbish.

I’ll never understand why so many people liked Babadook, it was so silly haha ”babadoooook” ..me and my mum kept saying it to each other and laughing.

It is a new and interesting development in the horror genre.

I must admit that I found the graphic portrayal of the effects of mental illness in Babadock deeply affecting and was left feeling moderately disturbed. When I got home afterwards I had to watch the Sound of Music a couple of times before I felt better.

My favourite of these is “The Others”.

Mama and the Babadook are my favourite so far. Couldn’t sleep for a while after watching the Babadook though…

Neither of these comes together as a cohesive and scary story, like The Exorcist, Don’t Look Now, The Shining or The Wicker Man.

The Babadook is very disturbing and there should be some warning to people who may be suffering from a similar illness.

New golden age of horror!

I felt like there was a cold hand on the back of my neck throughout watching any of these movies.

I loved this article: I’m particularly interested in the connection between the mother’s body and the home as subverting gendered spaces.

I’m wondering what you think of the idea that these subversions can be empowering to women? Just in virtue of depicting a women (even if it’s through horror) as dealing with feelings of resentment toward their children? I mean, this is coming from a cis-male perspective, so maybe the question is ridiculous.

I think this is a great point, and I’m sorry I didn’t see this earlier!

While writing the article, I definitely thought that creating a rebellious and ‘dysfunctional’ mother figure (dysfunctional by the standards we have of motherhood of course, often moulded by patriarchal and Freudian beliefs) actually empowered them to an extent, and I would love to have more time to explore this idea. Somehow by rejecting the motherly role, the oppressed sexuality, the space of the home and the need to detach herself from the child, she refuses patriarchal values. This empowers her which makes her ‘scary’ and ‘dyfsunctional’ to patriarchy’s and society’s eyes. I definitely feel like I didn’t expand that point enough.

But at the same time, you are right – those mothers come from a male perspective anyway, so are they actually constructed as empowered women? Do you need to be ‘dysfunctional’ according to society to actually become empowered? Does it mean empowerement comes with rejection of the child, extreme behaviour, signs of mental illness, a rebellious and abject sexuality, and a monstruous nature? I don’t really think so, again these are partiarchal views somehow. It really is a tough one!

Watched The Babadook and It Follows in the same week. Preferred The Babadook over It Follows,but on the whole both movies offered genuine moments of astutely measured jolted horror.

That’s a good way to put it. I found Babadook very sad, but I found It Follows genuinely creepy.

This article is very timely because I am just re-watching Coraline and have recently re-read the Victorian short story, “The New Mother.”

In Coraline we have the mother figure bifurcated: the normal mom and the monstrous mom. Strangely, the monstrous mom is actually more nurturing than the real mom. She is attentive and desirous – but she also will most likely abandon you when she gets bored and might possibly eat you.

So the mother figure always has a side to her that is threatening.

This is really illustrated in “The New Mother,” a story of a broken, single-parent family. Here we see the mother figure split into three parts: the traditional mother who loves but the love is conditional and she will walk away; the trickster mom who lies and inverts; and the scary, partly-mechanical, partly male New Mother.

The New Mother enters the scene once the two little girls have driven off the traditional mother with their bad behavior. The traditional mom has gone to re-unite with the long absent father. The New Mother could be argued to be a return of both the masculine and the feminine, in one form. Unfortunately, the masculine side seems to warp and overwhelm the feminine side: the New Mother has no tender feelings and is aggressive and rapey, with her phallic tail.

Lucy Clifford, the author, had no intention, I believe, of representing mothers as such. It is just that in her haste to scare children straight, she tapped into some pretty primal fears we all have about our mothers. After all, our mothers had incredible power: the power to soothe us or the power to torment us or, worst of all, the power to ignore us.

Perhaps having a mother is something we never get over…

Fascinating, thanks so much for this! I haven’t watched Coraline in its integrity but would love to, especially after all you said! And New Mother sounds fascinating.

The boy in The Sixth Sense was fatherless, too.

I loved your analysis on this subject. Thanks for posting!

Very well researched. You explain Kristeva’s abject other concept well, and I like how you linked it to the domestic sphere. Thanks for sharing.

Very well written article, it is a fascinating topic and good to see it so well represented on screen (the pressure of patriarchy’s mother role) but does anyone know similar films that present a more empowering conclusion where the woman usurps the pressures of patriarchy?

I think The Witch is also working on similar questions of the vulnerability of woman in the patriarchal organisation of society.

Very interested mini-treatise examining the subtext of horror.

I really enjoyed learning for this article, it was well researched, analyzed, and presented. I feel like I have a better understanding of the sub-genre of horror and the psychology of single parenthood now.

The Others was one of the first horror films I had ever seen. Since I was so young at the time, I never realized the depth to it until I got older. This, however, uncovered a whole other layer to it. I will definitely be re-watching this movie in with a new perspective and then watching the Babadook right after.

Although I haven’t seen the movie ‘Goodnight Mommy’, I think it might be of interest to you! I’m still trying to muster up the courage to watch it.

I would argue that many horror films do not use the role of dysfunctional mother as enough of a subversion of the tropes we so often see in other films. While it invites empathy, expresses more facets of personality, and underlines our mistrust and paranoia of motherhood, does it really take the undying mother-protector-at-all-costs trope and turn it enough on its head?

Great and well-researched article, but I would argue the dysfunctional mother role could do more.

Oh yes I agree with you, but unfortunately I am not the one who makes those films aha! Of course the dysfunctional mother role has a lot more facets to explore, and directors could do much more of it. And of course not all horror films use this as a trope, thankfully! It’s a rich genre and I never said all horror films used this trope! It is just one of them, and an interesting one to explore 🙂 like you, I’d love to see it develop more and I do have higher hopes after watching The Babadook, a more contemporary comment on women’s roles in society, the way they are regarded, and the constant connection to mental health issues. And it was made by a woman – so there is hope to see new things around the subject!

Oh, absolutely! Sorry, I wasn’t trying to imply that that’s *your* job, lol, or that your article wasn’t doing enough (it was great :] ). The Babadook did a lot of heavy lifting with regards to motherhood that so many movies have fallen short of; I’m very glad it was made.

I suppose what I meant to say is I wonder what the next step is for this role of dysfunctional mother? How can it progress and evolve, both in a way that is critical of previous representations and makes mothers more… “real?”

Oh don’t worry, I didn’t take it badly aha! I agree with you completely. Let’s discuss this in the future! 🙂

😊👍

Changeling can tie into this since it showed how the mother stopped at nothing to find her son and everyone thought she was going crazy. It just shows how a mother figure is hard to define and her love is hard to understand.

Great analysis! This was very interesting to read. I would like to point out a few moments a bit later in The Babadook, though, that I think wring some significant changes on the “maternal horror” genre by subverting the expectations associated with it, which you detail here so carefully.

First, in the first half or so of the film, we identify with Amelia, and we view Sam the way you describe: overly attached to his mother, stifling & repressive, his belief in monsters & building of weapons a sign that he is so maladjusted that he might become a serious threat to himself & others. But, once Amelia becomes the Babadook, our sympathy shifts to Sam, and it turns out all those elements of his personality we viewed as unnatural/maladaptive are totally essential to saving him and his mother. He uses the weapons to avoid death and incapacitate her, and in what is for me the film’s most moving sequence, rather than killing her or trying to escape, he reminds her of his promise never to abandon her and to defend her from monsters, and succeeds in exorcising the Babadook.

Second, in the film’s final scene, we see that the Babadook can’t be truly defeated, but neither does it spell inevitable doom for the characters: instead, Amelia takes Sam to the once-off-limits cellar, now seemingly the Babadook’s permanent residence, and together they feed it earthworms before returning upstairs to celebrate Sam’s birthday (something Amelia had avoided because it reminds her of her husband’s death). In other words, Amelia has learned to cope with grief and mental illness (her own and also Sam’s) through acknowledging it and taking appropriate steps to keep it under control, rather than trying to avoid it through repression (as she had been doing by e.g. not letting Sam go into the cellar) or to destroy it completely (as we perhaps thought had happened in the film’s climax).

Politically, I think these revisions to the formula do significant work. The final act subverts generic expectations, in the process suggesting that:

A) we shouldn’t be so quick to judge children as “maladjusted” and hence products of poor parenting (Sam turns out to be wise beyond what we or Amelia expected), and more importantly

B) a healthy, happy home life is possible for single mothers and their children, even for people as troubled as Amelia and Sam (their happy ending comes through recognizing and dealing with their emotional issues together, not through the addition of a father figure: the coworker with a crush on Amelia, whom we might expect to show up and save the day, turns out to be a red herring).

Never thought of it like this…but upon reflection, I do think the best horror films are the ones who externalize the terror that goes on within a human’s mind and body, like a crazed man swinging an axe at his sprinting kid. The Shining will always take the cake for me.

I would want to say that I have never thought of this like this either… But good to know. Finding blogs like this and reading what they offer provide with. The Shining is a great movie indeed. http://findwritingservice.com/blog/history-of-formation-of-horror-movies is a great publication on horror movies. Look it up and enjoy watching horror movies. They are the best! Only those, which are shot by true professionals though like Alfred Hitchcock, for instance.

Maternity and horror have a long history in film and literature, and you’ve very skillfully unpacked some of most evocative of late. What’s your view of Mama and the mother figures who compete to care for the children?

I also think you’re observations about motherhood and sexuality/sexual desire are important to the exploration of what makes a mother “horrible.”

So glad you introduced Lacanian theory into your discussion, too.

This was an amazing and insightful article to read! I personally find this topic so compelling because of the way that it warps our image of motherhood into something so despicable and demented. I feel like the best horror films and literature are able to take something we are most comfortable with into something strange and dangerous.

This article is incredibly insightful. 😀 Though I may have to add that, personally, I’m surprised you didn’t mention Rosemary’s Baby or The Exorcist in this, as those two are by far the most insightful horror films in regards to maternal elements.

Yes, we forget how hormonal post partum period is for women. It’s like biology is like here all these fun drugs to make new life, and if you pop out a baby through your vag if you are lucky the hormones self correct in a couple of years if you have no other children. But most women have their second child within about 16 months of their first child so their hormones don’t self correct plus puberty doesn’t end for most people until their mid twenties. It’s like we have generations of adolescents raising their adolescent children. There are so FEW adults raising children. Adolescent development doesn’t officially end until 30 years of age. Most women have their first child at 24 on average. I’m not saying child abuse, but it just is what it is: blind raising the blind.

by the way to me the exorcist about a not so mysteriously raped young virgin who is forced to get a late term abortion that goes wrong on top of the catholic guilt… all the symptoms of the exorcist mirror botched abortions and incest/ sexual assault from a loved one.

What do you think?

I’m so impressed by analysis with works cited! And the calibre of discussion. I’m scared to be a mother. In the modern age, mothers often feel like they are raising the oppressive enemy. On the other hand, mothers raise sons to be completely dependent on women. Many mothers do not show men how to build a home and take care of themselves without a woman. Men born to mothers so desperately dependent on men they hate their sons deliberately hamper their development by refusing to show men how to care for themselves through skills like cooking and cleaning so on the one hand they raise the man they hate a men incompetent of domestic harmony so that the mother in the old age can claim the son’s house hold. This claiming of a mother of her son’s adult household is an insurance policy that says “when I;m old you will take care of me because I have not taught you how to take care of yourself and I have made you believe all other women are incompetent.” So the cycle of disappointment between men and women begins again.

The first rule of fight club…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QOZDKlpybZE

Very interesting article! I’m just thinking aloud here, but it might be fun to apply an analysis like this to Ich Seh, Ich Seh/Goodnight Mommy (Fiala & Franz, 2014). I don’t know if you’ve seen that film or not, but it’s another one that seems to explore these themes – although in different ways.

Great article! Timely read, as I have been researching a lot of the same material for my Honours film project. I’m new here but am looking forward to reading more by you. Thank you!

Yesssss — the strongest horror, for me at least, is that which means something. Symbolises something. Love it love it

Wonderful story!

The title really grabbed me, and the subject headers were very useful for navigating.

I would have liked for the subject of grief, particularly in Grace and Amelia’s cases, to be covered a little more thoroughly, at least in terms of how grief interacts with isolation and sexuality. The article also totally ignores the fact that Grace’s children were violently allergic to sunlight, and that was a big part of Grace’s fear and also her entire motivation for keeping the curtains closed all the time. By painting Grace’s desire to contain her children as coming from a desire to trap them, it considerably weakened the arguments concerning her character.

There also was a bit of a missed opportunity to compare mothers like Grace and Amelia with characters like Mama from the Guillermo del Toro film, where the symbolic is made solid and the mother figure is built from the ground up as a literal monster.

Otherwise, a very interesting subject which brought up some solid points and made me think. Thank you for sharing.

such a fantastic analysis of the dysfunctional mother character.

Aliens (1986) is another unusual but definitely applicable example of everything you describe. Interestingly, it is a science fiction, far future story exemplifying exactly these same fears of women’s power, desire and single maternal childrearing but exacerbated by fears of where feminism will take us in the future. This appears in the form of the alien Mother Queen alien whose sexual insatiability and virtually limitless asexual reproductivity is so grotesquely androgynous through all of its vaginal imagery and yet phallic and penetrative through its ability to essentially rape humans. The result is a truly horrifying femininity which can only be defeated by the nuclear combination of Ripley, Newt and Hicks.

Hi! Nice observations you made on horror films speculating on motherhood and its simultaneous relevance to psychoanalytic theories.

I was thinking about how virginity is used as a trope in some of the horror films like “jennifer’s body”, the virginity as the desirable as well as the potentially threatening element( indeed making it more desirable) in a problematic relation to the female sexuality. Both the ‘virgin’ and ‘mother’ though having diametrically opposite functions in the society, are indeed linked in this nexus of protection (for virgin) and repression(for mother) of sexuality. It is interesting to see how both of these categories are defined in accordance to their deployment of sexuality. The mother as the lack of it, and the virgin who is “un-touched”.

Hi! Nice observations you made on horror films speculating on motherhood and its simultaneous relevance to psychoanalytic theories.

A great follow up to this analysis could include ‘Hereditary’ (2018). I spent a solid hour or two reading up purely on the ideas of maternity and inherited female trauma, and think this would be super interesting!

This is amazing work. I think one of the coolest most accessible ways for men to learn about feminism and misogyny is to study horror films and critiques/analyses of them.

It strikes me the Hereditary might be a fantastic example of the Dysfunctional Mother. I would love to hear your thoughts on the film!!

Really great article here, enjoyed reading. I think this provides a really astute analysis of how these films convey a certain paranoia surrounding motherhood in our modern society that stretches back for multiple generations. Social commentary in horror films is becoming increasingly common, especially with directors like Jordan Peele tackling multiple important themes across loosely related films, but one less recent, specific director that has strong maternal themes throughout his work is Alfred Hitchcock.

It’s interesting to compare the role of the mother in Hitchcock’s suspense films of a prior generation to those discussed in this piece of writing, as the mother serves a very different role. Hitchcock uses the psychotic mother not as a metaphor for the confined and pressured mother of the modern age, but instead as a negative facilitator that brutally controls and manipulates her children, warping their minds and molding them into socially awkward and dependent people (see “Strangers On A Train for a great example of this).

This likely had to do with Hitchcock’s own mother being a very controlling and strict Catholic, which possibly damaged him as a child, along with his police officer father. Hitchcock’s conversion of a mother’s care from a pleasant thing to a menacing process is very interesting, especially compared with the modern horror depictions of the mother we see here. I think it shows the progress film has made, specifically in the horror genre, in conveying the norms we’ve come to establish in pop culture regarding mothers and women. Hitchcock’s rather sexist and vicious depictions of both his women and mothers are the product of another era, and while his films have aged well in their technical proficiency and excitement, his rather nasty female portrayals have not.

Article made me consider this. Awesome read!

Recently watched The Brood and your section on the paranoia around maternal sexuality is VERY relevant to that film. The main character is a woman who literally births manifestations of her trauma and rage, which are strange, murderous, childlike monsters.. Two men attempt to control her–her husband and this psychotherapist guy–and towards the end there’s a birth scene where she performs this sort of powerful display of her ability as a woman to give birth. Essentially, she’s in this glamorous white dress and “unveils” a bloody embryo that “hatches.” Watching it was pretty strange for me but reading what you have to say about it helps me think a little deeper about what it means.

Terrific article. The pressure of motherhood, the judgment and the oppressiveness of the home all drive the woman insane. I’ve never been a fan of horror, but I’ll have to watch the three movies you analyzed.

I particularuly like the films that have a sense of dread. which helps build up the supense for me

“Hence her fear of becoming a Bad Mother turns her into a danger as she conforms fanatically to the mothering role.”

The word “self-fulfilling prophecy” spring to mind.