Adapting Worlds, not Stories

We have a habit of judging adaptations in a different way than we judge anything else. In an original blockbuster (as rare as they are nowadays), we tend to review a movie on the quality of its storytelling, special effects, action, or performances. But we seem drawn to judge adaptations by their fidelity to the original. This article proposes one alternate way of evaluating and describing the work of adaptation by using an old standby of literary theory, chronotope analysis, as introduced by M.M. Bakhtin. My analysis here is by no means complete or prescriptive. I only hope to show how literary theory sheds light on everyday questions of adaptation. Moreover, I hope to show how we can critique adaptations without using notions of failure or success in terms of faithfulness. In the end, I want to celebrate the unique merits of adaptation without ignoring or sanctifying the source.

I’ve taken as my case study the strange case of Roadside Picnic by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky. 1 This Soviet-Russian science fiction novel (criminally under-read, I might add!) found more success in each of its cross-media adaptations: first, Andrei Tarkovsky’s acclaimed 1979 film Stalker 2 (one of the British Film Institute’s 50 Greatest Films of All Time); and second, GSC Game World’s 2007 computer game series S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 3 Roadside Picnic offers a great case study because the plot, characters, world, location, and even tone change drastically among its adaptations. In this case, how can we say these things are still adaptations? What ties the three pieces together?

I hope to show that Roadside Picnic and its adaptations engage in a remarkable dialogue about finding the “center” and, through that center, the meaning of post-industrial life. Despite the unrecognizability of the source material, the process of adaptation makes this cross-media conversation possible.

Roadside Picnic asks, “what is the center of humanity?” from a vantage critical of western consumerist values; Stalker asks the same question from a position of spiritual humanism; S.T.A.L.K.E.R. asks the question with post-Chernobyl skepticism of the Soviet program. Each adaptation has wildly different ideological concerns, but they all construct their worlds around a center that pulls in the periphery.

Introducing the texts and the ideas

At first glance, these three texts couldn’t be more different stylistically. Roadside Picnic is a pulpy sci-fi novella; Stalker is a slow meditation on nature; and S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is a survival-horror first-person shooter. Yet their worlds are shaped the same: each one takes place in an urban or suburban environment that has recently undergone a disastrous transformation. Moreover, each follows an outlaw’s journey to the center of an anomalous “Zone” left in calamity’s wake. Since the disaster, the Zone has grown into a mystical place where the laws of physics loosen their iron grip.

In each story, an object that is rumored to grant wishes lies at the center of the Zone. The protagonist of each text is driven by circumstance to find this wish-granter. To do so, however, he must cross a border—a point of no return—that transforms him and seals his trajectory inward. Finally, when each protagonist finally reaches the wish-granter, he is forced to face his essential nature (his own center) and must own their own shortcomings: they have nothing to wish for. Despite differences, Roadside Picnic and its adaptations share this center-oriented quest that reveals the nature of (the lack of) the protagonist’s desire. In each case, it is the structure of the world itself that generates the quest.

To make sense of these similarities, I will borrow Bakhtin’s concept of the “chronotope.” This choice is, to be frank, a choice: other tools may be better suited to other case studies. By Bakhtin’s definition, a chronotope is a relationship between space and time as presented in a text and represented by its syntax and grammar (whether written or visual). For instance: a long, winding, circuitous sentence, whose structure nests ideas, which serve to delay sense and add content, while hiding their true aim, deliver a “heavy” chronotope where the reading time stretches the referential (or fictional) time of the referents. Light sentences cover the core of the earth to the outer edges of the galaxy in half the words. Often, a chronotope analysis will compare which activities are summarized succinctly (“they trotted forward for three more weeks, breaking only for meals”) and which activities are expanded (“She stared at her daughter for what seemed like an eternity, paying particular mind to the way those lashes, so reminiscent of her grandmother, quivered slightly in the cold December air. It was…).

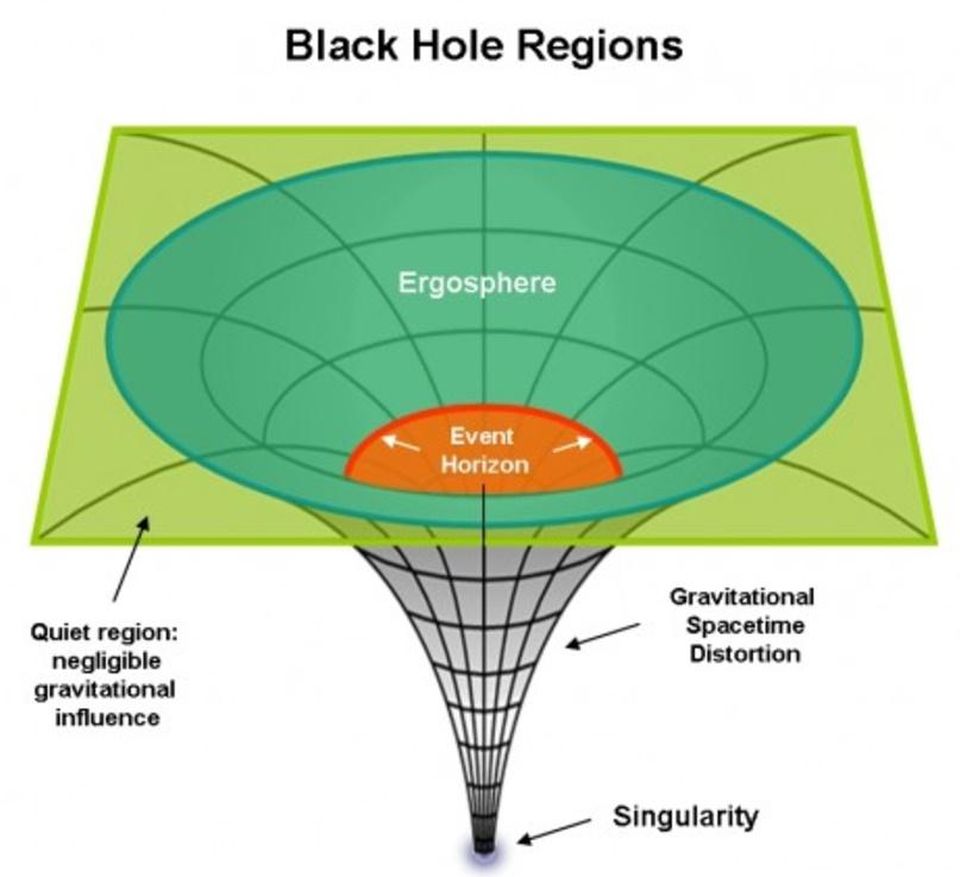

Bakhtin borrowed the notion of a chronotope as a metaphor (conjuring associations with the space-time of physics), and I find it helpful to develop metaphors to discuss individual chronotopes as well. In this light, the chronotope of Roadside Picnic and its adaptations might be best described as a black hole.

Roadside Picnic‘s spatial characteristics conform easily to this metaphor. Such a chronotope suggests four primary sections with different spacetime expectations: the quiet region outside the black hole, the event horizon that marks the boundaries of the black hole, the space-time distortion within the Schwarzchild radius, and the singularity. Let’s break them down in some detail.

The quiet region is the area of the text where the laws of the actual world are held. In Roadside Picnic and its adaptations, the quiet region establishes the adaptation’s ideological concerns. For example, Roadside Picnic is set in a North American town because its black hole (given the authors’ censors) could only exist in the American “quiet” of capitalism. As we will see, the quiet region across adaptations is always a town or city that has fallen on hard times. The everyday, in these words, is a broken promise.

The border between the quiet region and the Zone is the event horizon. Once a character crosses the event horizon, they are inexorably drawn toward the center of the Zone. At this point, however, they also transform: what is possible in the Zone is now possible for them as well. There, their wishes may be answered.

The Zone itself is a funnel of space-time collapse. This is the black hole’s space-time curvature, wherein time is expanded to the point that it seems to be simultaneously infinite and stopped. All space in this curvature is approaching singularity. At this point, time and space can now only be measured in relation to the black hole: one’s proximity to the center becomes the only relevant piece of temporal or spatial information. The laws of Newtonian physics break down and distort.

https://www.behance.net/gallery/53869529/Concept-art-to-Roadside-Picnic-TV-series

Finally, there’s the black hole’s singularity itself: the wish-granter that draws all in. If this point is reached, the narrative must end.

An analysis of this chronotope’s role in Roadside Picnic and its adaptations reveals a line of meaning that overcomes the adaptations’ surface differences and suggests a continued, deep interrelation.

Roadside Picnic

Roadside Picnic, a pulpy entry into the Soviet science fiction genre, is set in Harmont, a rural North American town. Recently, Harmont was the site of an alien visitation that left a “Visitation Zone” at the town’s center. These aliens never interacted with the citizens; they merely stopped by. The Zone is littered with discarded alien artifacts and physical anomalies: strange gravitational wells, spheres of time compression, and other marvelous impossibilities. According to one of the novella’s scientists, the Visitation was just a roadside picnic to the Aliens, and humans are like baffled woodland critters picking through the garbage they left.

Roadside Picnic follows Redrick Schuhart, a stalker. Stalkers steal into the Zone under the cover of darkness to recover artifacts and sell them on the black market. To do this, they must sneak passed a military border that protects the Zone’s perimeter. Red’s story culminates in the quest for the golden sphere: a famed artifact capable of granting wishes.

https://www.behance.net/gallery/53869529/Concept-art-to-Roadside-Picnic-TV-series

In Roadside Picnic‘s black hole, normalcy is established through the first scenes set in Harmont. Before the Visit, the town is shot through with a deep sense of ennui. The townsfolk wanted to leave and make a new life in a bustling city, but few had the means or skills. Whenever the novella follows characters who never enter the zone, the writing is characterized by meandering dialogue and constant reminders of the passage of time: the ordering of drinks, a change of venue after a bar closes, etc. The local bar, The Borscht, is an undeniably stagnant location filled with regulars. The resulting chronotope has the repetitious monotony of an assembly line. The effect is enhanced by the present-continuous narration:

The Borsch is always empty at this hour. Ernest is standing behind the bar, wiping the glasses and holding them up to the light. This is an amazing thing, by the way: anytime you come in, these barmen are always wiping glasses. . . without saying a word [he] pours me a shot of vodka. I clamber up onto the stool, take a sup, grimace, shake my head, and take another sip. The fridge is humming. . . I finish my drink, putting my glass on the bar. Ernest immediately pours me another one.

Roadside Picnic, eBook

Note how, in this passage, the repetitive language (“always empty,” “anytime”), repeated actions (the two sips), the breakdown of the act of sitting on a stool, and the present-continuous tense combine to create a monotonous, looping chronotope. Leaving the bar, Red immediately thinks about “how much money Ernie is making on us.” Capitalism is the only escape from monotony in Red’s vantage.

Since the Visitation, the youth no longer pine for a better life outside. Instead, they stalk into the Zone to find a better life within, picking through the garbage heap of Alien refuse. The Zone offers the possibility of increased capital from within, through hard work. They must overcome the government’s overbearing reach: as soon as the aliens left, the Institute erected a border wall around the Zone. The Institute is a mysterious body, dedicated to transforming recovered artifacts into discoveries and improvements for everyday life. Every stolen artifact, sold on the black market, distances them from this goal.

The institute’s border wall is Roadside Picnic‘s event horizon, separating the quiet region from the Zone. Anyone who sneaks past the military barricade and enters the Zone is instantly transformed. Inside, the laws of physics and modality become deliquescent, and this disintegration sticks to stalkers even after they return to Harmont. Their children are born with mutations (Red’s daughter looks like a monkey), and people spontaneously die around them. Nonetheless, the Zone calls stalkers to return because they can never be satisfied with their gains. One may take the stalker out of the Zone, but they can never take the Zone out of the stalker.

As a dystopian exploration of technological consumerism, Roadside Picnic‘s Zone encapsulates the Strugatsky brothers’ pessimistic view of capitalist societies. It offers only self-destruction through material obsession. The stalkers are gangsters, smuggling alien contraband that is literally mere garbage. The Institute could better human life with these artifacts through scientific study (at least, according to its mission), but the stalkers risk their lives to pilfer the artifacts before the institute can use them. This tension is made particularly salient in the book’s second part. Red is sent to the Zone to recover some hell slime, an artifact that dissolves anything it touches. Seeing its potency, Red decides to conceal the artifact instead of sell it. He is soon arrested by the police, and, knowing that his wife and daughter will fall destitute without his income, he sells the slime in exchange for his family’s wellbeing. Were the Institute to study the hell slime, who knows what could have been achieved. To satisfy his basic material needs, however, Red instead turns it over to a pair of men who plan to turn it into a weapon of mass destruction. Later, it is suggested their laboratory fails to contain the slime properly and thirty-five scientists die with over one hundred more injured.

At the novella’s end, Red (out of prison after serving his time) seeks the golden sphere to wish for enough money to leave the stalking business. However, a particularly gruesome anomaly, the meatgrinder, separates him from his prize. A whirling vortex that rends flesh from bone, the meatgrinder has only one weakness: after triggering, it falls inert for a short period of time. In other words, if one provides it with a human sacrifice, they may pass through themselves unharmed. Red must sacrifice some naive victim if he hopes to extricate his family from poverty through the golden sphere’s infinite wishes. And Red does just this, by tricking a young stalker, Arthur, into entering the meat grinder:

…And the boy kept walking down, dancing a jig, shuffling to his own

beat, and the white dust rose from his heels, and he was shouting at the top of his lungs, clearly, joyously, and festively — either a song or an incantation — and Redrick thought that this was the first time in the history of the quarry that a man went down there as though he were going to a party. And at first he did not listen to what his talking key was yelling, and then something clicked inside him and he heard: Happiness for everybody! … Free! … As much as you want! … Everybody come here! … There’s enough for everybody! Nobody will leave unsatisfied! … Free! … Happiness! … Free!”And then he was suddenly silent, as though a huge fist had punched him in the mouth. And Redrick saw the transparent emptiness that was lurking in the shadow of the excavator’s bucket grab him, throw him up in the air, and slowly slowly twist him, like a housewife wringing her wash. Redrick had time to see one of his dusty shoes fall off his jerking leg and fly high above the quarry. Then he turned away and sat down. There wasn’t a single thought in his head, and he had somehow stopped sensing himself. Silence hung heavy in the air, particularly behind him, there on the road…

Time passed, and more or less coherent thoughts came to him. Well, that’s it, he thought unwillingly. The road is open. He could go down right now, but it was better, of course, to wait a while. The meatgrinders can be tricky.

Roadside Picnic, eBook

Even though this passage represents a short moment, Red’s thoughts meander with no timely markers for three pages. The difference between this passage and the passage at the bar are stark: several seconds stretched over many pages, a preoccupation with physical spatial descriptions (“spatial emptiness,” “the shadow of the excavator’s bucket”), and no sense of time until the vague statement that time simply “passed.” Time becomes heavy like space; space becomes a vague yet active force like time.

As readers, we anticipate Arthur’s demise. But Red instead revises for us his description of Arthur —a mere object to Red, a “living key” in his own words—and thus stretches time further. In only a few meters, Arthur manages to dance, and skip, and find a rhythm in his step. He’s also able to shout several sentences in only a few “seconds” time. When the meatgrinder triggers, Red describes the trap as both “abrupt” and

“slow,” “transparent emptiness” and “seeable.” This is characteristic of the Zone: the black hole chronotope, where time seems to stop and minor and major events are given equal importance, as space flattens in singularity. The dust beneath their feat is as important as Arthur’s wringing. The characters accept these moments as normal because they are now members of the Zone domain: they transformed in their transit towards this center of a capitalistic desire.

Red’s need for material gain led him to kill an innocent who only wished for universal happiness. As space and time stretch, the reader is given the time to understand just how horrible Red’s final act is. When Red reaches the sphere, he has no wish: there is nothing he truly wants, and the narrative abruptly ends. There is no meaning in a world where an innocent like Arthur must be sacrificed for the transit into the center.

Stalker

Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker is the story of a nameless stalker, who leads people through a strange anomalous Zone left by a meteorite crash (perhaps) or a nuclear meltdown (maybe). The meteor’s crash site – an old nuclear power plant – is known as the Room, a transformed space capable of granting your innermost desires. In the film, Stalker guides two men – the Professor and the Writer – through the Zone to find the Room. Though the Room can be seen only a few hundred meters from the Zone’s boundaries, the journey takes substantially longer due to dangerous metaphysical traps peppering it.

The fictional world is structured similarly to Roadside Picnic‘s: a small industrial town offers our quiet region, dripping with aimless ennui and myopic alcoholism. The camera frame lingers even when characters enter and exit it, and the constant clicking of train tracks marks the passage of time while stuck in one space. The city is filmed in sepia tone, drained of color and homogenized into a malaise. The film’s opening scene offers a perfect example of this chronotope.

The Zone of Stalker was created in ambiguous circumstances, but the government instantly cordoned it off. Nature swiftly reclaimed the penned land. The Writer and Professor are both drawn to the Zone by its expanded possibilities: the Writer wishes for perfection in his craft, and the Professor aims to destroy the Room before it is used for evil. Notice that neither wish is explicitly capitalistic in origin. The Writer seeks aggrandizement, and The Professor’s assessment betrays his own inflated sense of self: he alone can arbitrate the Room’s usage.

Where Red is a brutish thug, Stalker is a spiritual guide: the pilgrimage to the Room allows Stalker to teach his companions the values of deference, faith, and respect. The sepia world of civilization is drained of hope, but in the Zone color returns. The camera still lingers, but space is no longer tightly framed and confined by walls and doorways. Instead, the camera pan and dollies among multiple focus points without preference: the travelers, a gun in the weeds, the distant room, a dilapidated truck, a clean stream. Compare the claustrophobic chronotope of the bar, where time passes in a small space:

With the swelling movement (so suggestive you can feel it in a still image!) of the Zone:

In the world of the small town, everything is confined, regulated, rigid, and repetitive. In the Zone, the sky above seems to offer a sense of possibility, and the camera can move freely in any direction yet still find an interesting focus.

Compared to the Roadside Picnic‘s Zone, Stalker’s Zone is utopian, a stand-in for the spiritual core of human experience accessible only when primal forces retake the land. At the center of Stalker‘s Zone is one’s “innermost desires,” granted by a bounded space, instead of a gilded object granting a wish. This Zone promises what truly lies in your heart of hearts – a spiritual contemplation unstuck from the militarized time of clicking trains and ticking clocks. In the Russian tradition, Stalker is God’s fool, leading men from this technological dystopia into the Zone as a spiritual retreat. While the industrial world is depicted with “depressive pointlessness,” 4 nature’s return in the Zone brings soft lighting, gentle pans over streams and softly tussled grass, and wide-open shots suggesting deference and sublimity. It’s important to note that Stalker does not blame capitalism for its ideological stakes: Stalker identifies urban industrialism itself as the source of ennui.

To get to the Room, the three travelers must pass through the meatgrinder: an invisible anomaly that, according to Stalker, kills any wish-seekers who lack faith. Whereas Roadside Picnic‘s meatgrinder requires a sacrifice, Stalker’s meatgrinder exists to ensure that “you are positive, good, honest people.” If you have faith in the goodness of your heart’s desire, you can pass unharmed. The meatgrinder starts as a twisting pipe, lit only by columns of sunlight slipping through cracks in its upper surface. This camera frames the space to disassociate time with space: the camera follows the Writer closely and tightly as he makes his way through, making gauging progress through the pipe impossible. The twists remove our ability to see ahead. It’s also impossible to gauge how closely Stalker and the Professor follow.

The meatgrinder opens into an eerie room filled with piles of sand. As in Roadside Picnic, the heart of the meatgrinder disrupts the relationship between the passage of time and movement through space. Stalker through a metal nut into the space to see if the trap will trigger: the two men drop, look up, and cower all before it hits the ground. Even the uneven ground, with its dune-like undulations, breach traditional categories of solidity and liquidity. The Writer is far ahead of the others, but then instantly huddled in a puddle that was missing from the establishing shot. The cinematography refuses to clarify the space: where is the puddle? How far is he from his companions?

Events happen simultaneously, but we’re allowed to see them separately and independently. Time and space are interrupted by the flight of a bird that vanishes without landing. A second bird flies, and lands as if the first never happened. The bird doesn’t obviously “disappear” or get destroyed by a trap, but movement through space is indeterminate because we glimpse “moments” absent their temporal/spatial context. Time grows heavy: every action is slow, calculated and given ample time to unfold.

This cinematographic approach enhances Tarkovsky’s fantastic vision of the Zone: we never learn if the traps or wishes are real, or if they’re an invention of Stalker’s mind to act as parables to teach the faithless.

When the Writer and Professor reach the Room, they refuse to enter. The Writer is afraid that he may not like his innermost desires: deep down, he may want something darker than he thinks. The Professor wants to destroy the Room, but, in the journey, develops an inexplicable understanding of its importance. Thus, its destruction is no longer his deepest desire. In short, industrialism has drained our scientists and artists of their faith in their own goodness. It is not that art and science are evil or decadent; the problem, for Stalker, is that art and science have lost a moral compass. The “organ with which they believe has atrophied,” he cries. Lying in the center of humankind is an empty room with an unlocked door, and we are afraid to open it.

Roadside Picnic looked at capitalist spacetime, and found at its center an unfulfilling black hole of greed. In Stalker, the empty room alludes to our loss of faith in the face of mechanized society. We aren’t sure if we are better than this. A “black hole” of hope draws us into contemplation, but technology has pushed us to the periphery of nature. We, the writers and scientists, look inward out of insecurity, not humanism. Faithless, mankind sits at the edge of great discovery while accomplishing nothing.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R.

In S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl, the player plays the “Marked One,” a Stalker who wakes up with amnesia and one task on his PDA’s to-do list: kill Strelok. This takes place in the Zone: the anomalous space left in the wake of a second catastrophic failure at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. In response to this failure, the government erected a border wall that contains the playable space. All stalkers – including the player – are trapped. The border was built around them – they are transformed by its presence and become one with the Zone, but not of their will. Stalkers venture towards the zone’s center for supplies and to find mysterious biological artifacts – strange living organs of intense power – left by the in the wake of catastrophe. At the center is the power plant, where an artifact known only as the “Wish Granter” exists.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is an open-world, first-person shooter, in which the player freely explores the virtual Zone in their pursuit of survival. This freedom means that the fantastic ambiguity of Tarkovsky’s film – which never “proves” whether its traps and anomalies are real or not – is not possible. A player can run into a meatgrinder, or any other anomaly, to verify its presence. They are “real” in the game world–they kill you. S.T.A.L.K.E.R.’s world is, like Roadside Picnic‘s, explicitly supernatural.

The non-player characters (NPCs), other stalkers, mutated animals, and monsters, are controlled by an artificial intelligence program called A-Life. This system allows the non-player characters to conduct their own day-to-day survival: they search for supplies, brave dangers, and engage in wars with other stalkers to control key facilities. This also means that the player will occasionally learn about an NPC who can help them uncover their identity, only to find that the NPC was mauled by a bear or walked into a trap on their own time.

This is a unique formal tactic for a video game and contributes to its chronotope: the world of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. treats the player with alarming disinterest. Traditionally, the world activates around the play character. When they are not in a room in most games, time freezes everywhere else. Space, time, and causality only exists when the player is there to see it. S.T.A.L.K.E.R.‘s constant unfolding recalls Tarkovsky’s cinematography in Stalker, albeit skewed to the demands of action-based gaming. Time passes evenly, in every nook of the game world, regardless of the current spatial focus. The narrative continues without the player’s consent, and stories emerge from the simulated interactions the A-life system allows. Crucially, this means the play is inexorably drawn to the center – so they can discover the truth before some NPC ruins it!

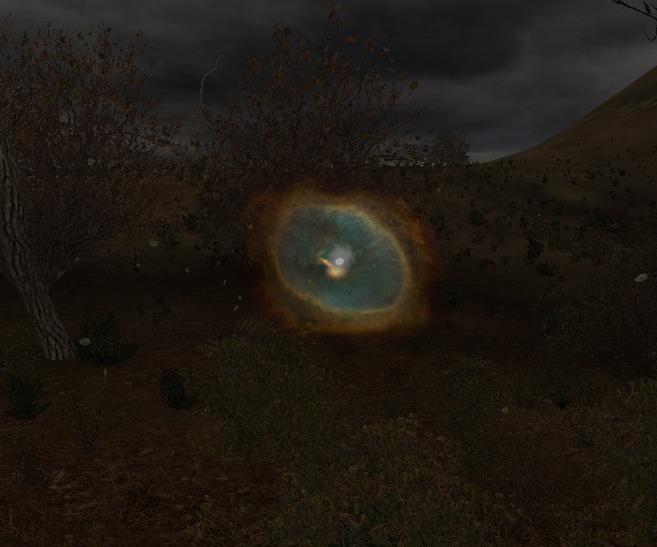

Though this set up alone could propel the player, the game imposes a traditional quest narrative: discover your identity. To do so, the player must travel to the wish granter. The Chernobyl power plant at the Zone’s center is only a few kilometers from the border (where you begin), but the twisting anomalies destroy the standard relationship between space and time once more. For example, a player may eye a shed for shelter or an ammo deposit a few meters away. However, anomalies prevent walking as the crow flies. Instead, players must read situational cues and navigate around invisible hazard. Again, we see the technique of challenging normal spatiotemporal expectations.

If you recall, Red was able to “see” the invisible force of the meatgrinder.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. makes this impossibility tangible by giving the player a few tools. First, the Geiger counter clicks depending on your proximity to the anomaly, literally transforming a spatial relation (i.e., distance) into a temporal one (i.e., periodicity of the clicks). Players can sense the invisible hazard through a breakdown of spatiotemporal categories. Alternatively, players can follow the eponymous Stalker‘s lead and throw metal bolts, which sizzle and fly through the air when they touch a trap. Once more, the player can judge the traps fixed borders by watching the resulting trajectory (movement through time). Finally, the player can lead enemies into the same traps, as Red sacrificed Arthur.

This equivalent to the meatgrinder distorts the relationship between time and space using interactive techniques. A regular player of games assumes that such a short path will take a short while to traverse. This is not the case: by throwing nuts or waiting for an non-player character, such short journeys may take a long while. Space fails to indicate time, and players are forced to spend more “time” in any one “space” than the genre often dictates.

What is S.T.A.L.K.E.R.‘s Wish Granter? Well, GSC Game World live in post-Chernobyl, post-Soviet eastern Europe. Tarkovsky’s film remains eerily prescient of the Chernobyl disaster, but this game responds to it. In the game’s narrative, the Soviet Union decided to use the Exclusion Zone surrounding Chernobyl for special research into collectivized thought. In other words, they are using radiation for mind-control. The Wish Granter is state propaganda (the quiet region of this world revealed in the end as the Soviet state), designed to lure the strong-willed for conditioning. The artifact is a man-made program of brainwashing. The center of humankind is ease of control. The protagonist has successfully reached the Wish Granter once before – hence, his amnesia at the beginning of the game. However, the brainwashing failed due to government ineptitude: his newly programmed task, kill Strelok, was impossible – he himself is Strelok. Your journey was sparked by a clerical error, generated by mistaken identity, whose semantic content demands self-destruction.

Our cross-adaptation dialogue about the center of humankind culminates here. In Roadside Picnic, the Strugatskys find a black hole of materialistic consumption at the heart of the capitalist Red; In Stalker, Tarkovsky finds an atrophied sense of hope and an empty space where our spiritual core should reside; In S.T.A.L.K.E.R., GSC Game World finds confused and impossible government dictates at the center of our Kafkaesque experience. One sees a dystopia in capitalism, one sees a dystopia in post-industrialization, and one sees a dystopia in the Soviet legacy. Yet all three stories use the same chronotope to explore the relationship between the world we inhabit, and the center of meaning.

A hard-line theory of adaptation may condemn the liberties taken by Tarkovsky and GSC Game World. For those who have not read, watched, or played, I assure you that my description makes them sound far more similar than they are in experience. Nonetheless, a chronotope analysis is just one of the many ways we can read this history and discover a more generous tale. We find adapters drawn to the very structure of Roadside Picnic‘s world, which draws the downtrodden into the center and then reveals the issues in the quiet region that drove us inward in the first place.

I hope the above models a generous approach to understanding adaptation that does not rely on notions of success or failure but on viewing each new version as another participant in an ongoing conversation. This article was inspired in part by the questions posed in JAbida’s post about film adaptation, The Art of Adaptation: From Book to Film.

Works Cited

- Strugatsky, Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. Roadside Picnic. Translated by Olena Bormashenko. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2012. ↩

- Tarkovsky, Andrei. Collected Screen Plays. Translated by William Powell and Natasha Synessios. London: Faber and Faber, 1999 ↩

- GSC Game World, developers. S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl. Published by GSC Game World, 2007. ↩

- Kowalczyk, Andrzej Slawomir. “Between Dystopia and Eutopia: Andrei Tarkvosky’s Stalker.” Imperfect Worlds and Dystopian Narratives in Contemporary Cinema. Ed. Artur Blaim and Ludmila Gruszewska-Blaim. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2011. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The novel really doesn’t have an end but a perceived one, you never see Red actually make his wish, you don’t know if another “meat grinder” is waiting for him just steps away after the novel closes, if he did make the wish you never really see the outcome of it as the nature of wishes in literature rarely pan out as promised, and you don’t even know if the spheres work because there is no evidence to say otherwise as any stalker who used them just vanish. The novel literally cuts off when things really get interesting in terms of what Red is going actually going to do and its outcome, which was my biggest issue with the tome.

“The novel literally cuts off when things really get interesting in terms of what Red is going actually going to do and its outcome”

Not to be pithy, but I’ve heard this complaint (the lack of closure) about the book before, and I’m afraid I just don’t understand it. The ambiguity was the whole point of the ending. “Finding out” what happened after/if Red made his wish would ruin it, utterly. The climax/payoff was the culmination of his character arc thus far; focusing on whether or not the wish granter was legit instead and how/why it works would detract from the experience and make it far less poignant.

In my opinion, of course. Obviously you disagree, but to me that was the perfect ending, and if it had gone on (which is a mistake the Metro series makes with its own version of the wish granter, among other things) it would have been far less meaningful. (I realize that part of the problem for some was reading the earlier English version with the HUGE mistranslation that made it so that the prologue seems like it happens after the ending, when it’s set well before.)

I originally discussed the specifics of the very ends of each (such as Red being cut off at the end of RP) but decided to cut it for space. You’re very right though: we don’t know if Red’s gambit works. Given the censorship environment, it was also probably the safest way to end the story ;).

Like folsks below, I actually think the ending also works better this way because it no longer matters: Red’s willingness to sacrifice another means he’s lost, whether he gets what he wants or not.

No, the novel had an end, not just a “perceived” one. I eventually ran out of pages. 😛

I remember seeing Stalker in the late 80’s on a bootleg VHS tape. Great film.

Last year I played a Delta Green module that was based around Roadside Picnic/Stalker. I realised fairly early on what the inspiration for the module was and so I think the GM was rather upset that the pitfalls that had been laid out were detected and bypassed pretty easily.

Stalker is the story of one particular adventure that takes place inside one of the six zones around the world mentioned in Roadside Picnic. There will be plenty of other adventures to be had. There will also be chance to investigate the impact of the Visitation Zones on the communities that are closest to them and the investigation of how humanity comes to terms with realising that there is intelligent life in the Universe and they think as much about humanity as we do about ants at a picnic site.

I want a TV series adapation now!

Interesting. Do you have a link to that module?

And yes, I think the TV series would have been quite the ride.

The beautiful thing about the setting of Roadside Picnic is that it’s completely ambiguous.

Which is why I don’t think a TV show could work: If it survives for more than a few episodes, then at some point it’s going to have to give some answers – fans will be clamouring for some kind of reward for their commitment at that point – and explaining the Zone is the antithesis of what the original story was about.

I can’t imagine how a TV show could present such an interesting mystery, but somehow also preserve the deliberate lack of answers that made the original story great.

Do you know of any recommended reading lists for Soviet/Eastern Bloc scifi?

As a Russian myself, I recommend Strugatsky brothers “The Doomed City”, because firstly: it’s a damn good book. Secondly, I think it gives great, subtle and wild representation of soviet people minds. Also, this book is full of awesome philosophical ideas, for which it was hidden from general public for a lot of years.

I would recommend to read almost all of Strugatsky brothers books (which were translated to your language). They are all very interesting in different aspects. E.g. “Monday starts at Saturday” is a humorous story about programmer.

Though they dreamed of communistic future, keep that in mind. Their worlds probably will look foreign to the western reader. And there are some references to the russian culture. But translations probably should take that in mind.

Memories of the Future by Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky

Stalker is positively uncanny in how it anticipates the Chernobyl disaster a half decade before it happened. You go to the exclusion zone today, and it looks like something out of Stalker.

And to make the coincidence even more eerie, much of the filming of Stalker took places in waters that were either dumping grounds or were downstream from some chemical facilities, and Tarkovsky, his wife and the lead actor would ALL die from aggressive forms of cancer within twenty years.

Any good science fiction focusing on the genre/category of the zone?

The Lovecraftesque stories by Caitlin R. Kiernan in her “Black Helicopters” and related works fall into this too, I think. I liked them quite a bit. (But then, I liked Vandermeer’s “Southern Reach” trilogy, too.)

If we’re adding novels then Robert Silverberg’s “The Man in the Maze” should be mentioned.

I have to argue about The Zone genre needing us to “not know”. The S.T.A.L.K.E.R games pretty explicitly state exactly what is going on with it’s zone and various protagonists, why the anomalies exist, ect.

The game SMT Strange Journey! a zone expanding from Antarctica

Now I’m wondering if Kojima’s “Death Stranding” will fit into the Zone subgenre. I already figured it was “The Postman, but weird,” but now I’m suspecting there’s more than a little Roadside Picnic to that game’s world.

The Gone-Away World by Nick Harkaway. It’s pretty cool in that The Zone is basically any part of the world that isn’t kept reletively stable and sane by the Jorgmond Pipe.

Roadside Picnic should be required reading but there should be no requirement to dumb it down with an adaptation.

A very nice insight into the nature of adaptation. Each of the media formats mentioned (literature, film, and video-gaming) have unique elements that limit what they can depict effectively. Stuff has to change, in short. I appreciate your efforts to encourage nuance on cross-media criticism!

Amazing article. I would like to say that I know my sci-fi stuff, but I’m really a fraud. I didn’t know this book, I’ve never seen the original Solaris, and I understand that Polish sci-fi is the schniz right now, but couldn’t tell you where to begin.

Get yourself a copy of the original Solaris, a spare 3 hours, and watch it. Even better watch it back-to-back with 2001: Tarkovsky supposedly made Solaris in an attempt to one-up Kubrick after he had seen 2001.

If it makes you feel any better, I have owned the Robert Rich/Lustmord album for years yet didn’t realise it’s connection to the book/film!

You can download roadside picnic free online, legally too I believe. Its worth a read even if its just for the pure Russianness of smoking a cigarette in the shower.

Here most of us are frauds, honestly.

I’d never heard of the book or film or games, but you have me really curious, and may have to hunt them down now.

This needs to be adapted more like a three part mini series, like the BBC day of the trifids mini series.I remember seeing Stalker in the late 80’s on a bootleg VHS tape.

The film, which I still watch at least once a year, took me to the game. The game took me to despair (I could never get it to run properly and I’m terrible at shooty games). Finally I read the book, which was not what I was expecting at all after the film and the game, but still a good book.

I had read Roadside Picnic a while ago and thought it a little bland, which was probably my fault as a reader.

The audiobook just popped up recently for me on Libby (free electronic and audio books with your library card) and I thought I’d listen to it for a little bit. Fantastic narration by character actor Robert Forster. You might not recognize his name, but you’ll know his voice. I ended up devouring the thing in like three days. You know an audiobook is great when your spouse knocks on the window of your car and asks why you’ve been sitting in the driveway for 40 minutes.

I actually listened to it instead of re-reading it the most recent time! It is a great audiobook and the new translation is nice. It also fixes some of the odd choices in earlier English-language translations (such as explicitly setting it in Canada).

See Made in Abyss for an excellent manga/anime version of the “zone”. Be warned that it is super compelling, but it also gets VERY dark.

Will definitely check it out!

I really think the “Zone” is a subset of “The Hero’s Journey”, which is the basis of almost all speculative fiction. It goes back to early stories by the Greeks and Romans of far off lands and has continued in fiction like Gulliver’s Travels. The hero’s journey allows for an infinite number of settings, encounters and experiences. The hero typically has a goal and encounters many situations along the way that are metaphors for current social issues and life in general. Almost all post-apocalyptic stories are examples of the hero’s journey.

The making of adaptations of Roadside Picnic seems to cursed or something.

The movie Stalker by Tarkovsky that was released is actually second version of that movie, as the first one was shot, but the film on which it was shot wasnt properly developed(or maybe spoiled purposefully?), so after loss of pretty much whole movie MOSFILM wanted to shutdown its development, but Tarkovsky persuaded them to make it as two-parts movie, to push deadlines and get some new funds to shoot the new movie.

As for the differences, the first version had obviously larger budget and even involvement of soviet army, supplying many more tanks for the enviroments, also story-wise it seems to have been much closer to the book, than the final movie (you can hear some more info in a really good “Interview with Rashit Safiullin” you can find here on youtube.)

STALKER game also wasnt concieved without issues, the final game seems to be also quite far from the original goal of STALKER Oblivion lost.

And after success of the games, GSC even announced STALKER Tv-series, which unfortunately died shortly after with the end of GSC. Fate of Stalker 2 game also doesnt seem to be getting conclusion anytime soon.

There was even Czech TV-movie adaptation of Roadside picnic called “Návštěva z Vesmíru” (Visit from space) in 1977 so even before the Stalker by Tarkovsky, but it just once aired in Czech TV, there is couple of accounts of people who saw it, and even people who were part of the shooting, by which it seems it was the closest thing to book so far.

But when people asked the TV to air it again, it came to light that the Czech communist leadership at the time, didnt like the philosophical themes of the movie, and it was silently destroyed shortly after it was aired.

Also there some other stalker-like projects that did get finished, like finnish movie Vyöhyke (Zone), which you can find and see here on youtube.

Or also some movies by Konstantin Lopushanskiy (guy who was already in production crew of Tarkovsky s Stalker) like Dead Man’s Letters (1986), Visitor of a Museum(1989), and The Ugly Swans(2006), although they dont reach the qualities of the Stalker by Tarkovsky, they quite nicely replicate/expand upon its atmosphere, with quite differently pointed stories.

Plus there s a movie Третья планета (The Third Planet) from 1991 by Aleksandr Rogozhkin, telling another story of the zone from a completely different angle.

And also there s a russian TV-series called Zona, which is still in-development, but similarly to Roadside picnic TV-series it seems to have problems with funding.

It’s interesting the way all these different versions try to respond to the Soviet Union. It seems like the original tows the Soviet party line pretty well (capitalism bad, government knows best, etc.) while the others are more subversive. They all take the idea of a Zone, but interpret it in very different ways depending on, seemingly, how the Soviet Union would have been portrayed by the respective creators.

Very interesting, especially the breakdown of regions.

I played STALKER: Shadow of Chernobyl when it first came out. To this day, that is still my favorite game EVER made. Stalker is my favorite movie and Roadside Picnic is my favorite book!!

Stalker is my favorite Tarkovksky film and my second favorite film of all time but let’s be honest it is a piss poor adaptation of the book. Proof that a bad adaptation can still equal a great film or films.

Great post! I’ve played all the games multiple times as well as seen the movie and read the book, all of which I love. I recall that they left the ‘alien’ thing fairly open in the book too, only theorizing about it.

That’s a fair point, there is much talk of the aliens in the book but its just our characters speculating.

Stalker is so good. The game, when it works, is also good.

The games were just brilliant, so much more involved than similar FPS RPGs.

Roadside Picnic has been very influential. Vandermeer’s Southern Reach Trilogy is perhaps the most obvious example.

M John Harrison’s fantastic Kefahuchi Tract trilogy is another.

A great use of Bakhtin’s concept of the Chronotope! I was very impressed at how it was applied so efficiently throughout your analysis of the 3 works.

Lovely read. The Metro 2033 novel and game do a great job of recreating that atmosphere that Stalker had. It feels like the reincarnation of that world.

I believe some of the developers from GSC who helped create the stalker games also worked on Metro. The author of the Novel, Dmitry is also inspired by the stalker universe as roadside picnic is pretty much a Russian national treasure.

video games has no relation to the Strugatsky’s novel except only the word “stalker”. And Tarkovsky’s film is also very far from original book.

One thing I love about some of the LoveCraft stories is when the heroes, protagonists or humans lose, fail or die. It’s just unsatisfying and awesome at the same time. Like holy shit, the humans lost, meaning we are all screwed. It was inevitable that we would eventually get killed by something we stood no chance of stopping in the first place.

Holy sht. U just explained exactly what I felt when I was about 12 and looked out the window of a moving car.

Never got around to watching the film but really loved the games (especially when you added the mods to them).

Only saw the Tarkovsky film recently thanks to the Criterion reissue and it is a mind blowing piece of cinema if you can handle the leisurely (to overstate it) pace. I’ll definitely revisit before the end of the year…

I tried reading the book a few years back but it must have been a badly translated version. I couldn’t get through the weird syntax to finish it.

One of my favorite sci-fi novels of all time.

My exposure to this is through the Tarkovsky film, which is a brilliant and gorgerous movie, but one that take a considerable amount of patience to sit through as it luxurates on statuc shots of running water and swaying grass for about a third of it’s running time.

Highly recomend it, but be bear in mind it’s really slow.

I played all the games (still playing. 😉 ) read the book (and many others from A&B Strugatzkij) and saw the terkowskij film…

Alexey art is spectacular.

Fantastic article! I learned so much.

dystopia can be the world after the catastrophe – the worlds in the article fit the bill!

Great conflation of three remarkably distinct, but thematically conjoined works. At the centre remains, the “black hole of greed,” to which we are all, to each other, nothing but a “living key.”

Brilliant, and especially resonant now, if these early months of the Plague Years.

A brilliant article. I will now use this knowledge when I try and reread the books.

Highly educational article. Superb.

one just wanders what will become of the road chronotope in post-Covid age..

Andrei Tarkovsky is one of the few Russian filmmakers whose works I have seen. His complete dedication to his craft stands through in his films. I immensely enjoyed watching Stalker, Andrei Rublev, Solaris and Ivan’s Childhood.

An interesting article, I’ll need to check this out.

To begin with, every piece of artwork is bound to carry some sort of traditions. In regard to the adaptation/original question, if we are to view a piece of work separately (instead of constantly comparing it to its “original,” I would suggest that going forward we should simply treat it as a standalone piece of work rather than continue comparing it against its original. For example, Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story (2019), to me, was strangely reminiscent of Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage (1973). Even at some point in the movie Baumbach paid a little homage to Bergman. This is, of course, to the eye of a huge Bergman fan. And interestingly, most media articles never brought up Bergman and his TV series. Even though I had the urge to compare this film with Bergman’s TV series, I never did. I simply treat it as Baumbach’s masterpiece. In short, my (current) view is focusing on the “new” work might be a more constructive way of seeing films as well as all artwork.

Your article provides a fascinating perspective on the often-overlooked aspect of adaptation – the adaptation of worlds, not just stories. It is intriguing to consider how a single world can be interpreted and extrapolated in countless ways, given different contexts and media. The adaptation of a world allows for a deeper exploration of the themes and ideas that underlie it, and it can also breathe new life into the original work by introducing it to new audiences or giving it a fresh perspective.

Your analysis of the various approaches to adapting worlds is thorough and thoughtful. It is fascinating to see how different media can shape the presentation and interpretation of a world – for example, how a video game can use interactivity to immerse players in the world and allow them to explore it at their own pace, while a film or TV series might emphasize the visual and thematic aspects of the world to create a more cinematic experience.

Overall, your article prompts us to reconsider our assumptions about adaptation and recognize the many ways in which it can enrich our understanding of a world or story. It also highlights the importance of understanding the source material and the creative choices that went into its original conception, in order to explore and adapt its world in a way that is faithful to its core themes and ideas.

Stalker is one of my favorite movies, although I have yet to read the original novel. I think a great example of this is in Blade Runner, both the original and 2049. They focus on adapting the world as opposed to following the narrative and characters to a t. The world is a character in and of itself. Other examples I feel like include the Lord of the Rings films and Coraline.