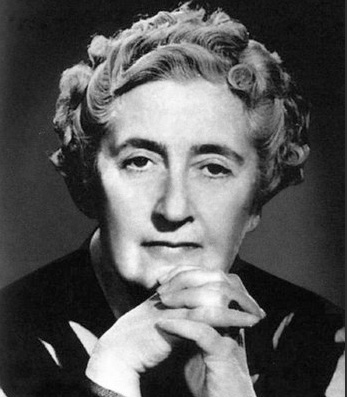

And Then There Were None: Agatha Christie and Her Deconstruction of the Mystery Genre

Agatha Christie has been hailed as a prominent figure in the flourishing of the clue-puzzle genre in the golden age of crime fiction between the two world wars, the “Queen of Crime” who constructed and consolidated the classical form of crime fiction that has enjoyed enduring popularity. What is often overlooked, however, is how playful and even unconventional she can be with the genre format in order to explore thematic complexity in her novels. And Then There Were None (ATTWN) is just such a case in point. On the one hand, it is easily recognisable as a classic “whodunit” story; but on the other hand, it also flouts many of the genre conventions in terms of setting, plot and characters. It can be argued that Christie’s deconstruction of the genre rules serves the novel’s thematic purpose. In other words, through the imaginative, unconventional engagement with the form, the novel explores unsettling themes of crime and punishment. Instead of offering comfortable solutions, it stirs up ambivalent moral questions related to justice and judgment that have no easy answers.

Murders in a Bright, Open, Modern House

What first makes ATTWN unusual among typical mystery novels is its setting. The most characteristic form of the golden age crime fiction is said to be the “country house murder mystery” (Horsley 31): a puzzle game with reader involvement in mind, intriguing clues, red herrings, multiple inter-related suspects, a labyrinthine plot, elaborate methods of homicide, and the ingenuity of a detective to bring about a satisfactory solution to the puzzle—all within the setting of an old English country house. The murder mystery of ATTWN, however, is set in an indisputably modern house, albeit the only house on a small island, cut off from the world. The dissimilarities from the old English country house are emphatically highlighted. There is no “creaking wood” or “dark shadows” to give “an eerie feeling”; the house was the very “essence of modernity,” “flooded with electric light,” “new and bright and shining,” with “nothing hidden,” “nothing concealed,” and “no atmosphere about it” (Christie 64–65). Ironically, as the narrator points out, “that was the most frightening thing of all” (65). Very soon in the narrative excitement turned into horror, the house bespeaking luxury and comfort of modernity became a slaughter house and hell of psychological torture.

More importantly, this modern house on Soldier Island, “a world of its own … [a] world … from which you might never return” (29), is where the characters—representing diverse social strata and backgrounds—were relentlessly pursued by their own conscience and mutual judgments, with their past transgressions laid bare, and where every one of them was mercilessly executed for offences for which society’s law had proved to be powerless. “Breaking” the genre rule of setting, Christie made the modern house set on an island—“which is a world of its own”—highly suggestive for a symbolic representation of the modern society of her own, where baggage of hidden social transgressions, mutual distrust and perpetual sense of insecurity lurked under the false bright prospects of modernity.

A Nursery Rhyme for a Plot

The second and also most remarkable aspect of Christie’s genre rule “breaching” is the novel’s plot structure according to the nursery rhyme of ten toy soldiers, which determines the number, order and manner of killing of the characters. The structuring nursery rhyme is introduced early at the beginning of the plot, in chapter two, through Vera’s perspective. The ten guests were also physically represented by the toy figurines that disappeared one by one as they were killed off. The narrative also closes with the figurines. Vera, the last survivor, even self-identified with the last figurine; “conscious of clasping a little china figure,” she went to the noose:

And of course that was the last line of the rhyme,

‘He went and hanged himself and then there were None…’

The little china figure fell from her hand. It rolled unheeded and broke against the fender. (Christie 222)

Such a structure is neat and fantastical, arousing readerly curiosity and fascination to see how it can be actualised. Christie considered it such a great success herself that in the note preceding the story she noted: “Ten people had to die without it becoming ridiculous or the murderer being obvious. … It was clear, straightforward, baffling, and yet had a perfectly reasonable explanation; in fact it had to have an epilogue to explain it.” Using the structure of the rhyme to create an intricate plot shows, however, not only the novel’s aesthetic appeal and technical masterfulness; it also bears significance on its thematic development.

One direct implication of using the nursery rhyme to structure the plot is the abandonment of the classic double-plot structure of the mystery genre. Tzvetan Todorov defines the structure thus:

[The whodunit] novel contains not one but two stories: the story of the crime and the story of the investigation. In their purest form, these two stories have no point in common. … We might further characterize these two stories by saying that the first—the story of the crime—tells “what really happened,” whereas the second—the story of the investigation explains “how the reader (or the narrator) has come to know about it.” … The first, that of the crime, is in fact the story of an absence: its most accurate characteristic is that it cannot be immediately present in the book. (44–46)

In other words, the dual structure of a typical whodunit novel is marked by a “temporal displacement” (Pyrhönen 49) in that the story of the crime is past and invisible, whereas the story of investigation is the one that is present and through which the crime is made visible and brought to light. The narrative normally ends by bringing the reader back to the past. Because the narrative shape is past-orientated, the double-plot structure engenders a “restoration of the equilibrium that the originary crime had so drastically disrupted” (Malmgren 122).

In ATTWN, however, there is only one story, which is at the same time both the story of the crime and the story of investigation. The crime does not belong to the past and is not hidden, but unfolds in present time before the characters’ (and the reader’s) eyes, precisely according to the manners prescribed by the nursery rhyme. The story ends where the crime is accomplished, and offers no solution in the narrative proper for “the restoration of the equilibrium” spoken about by Malmgren. Instead, it leaves the reader not only baffled about the who, how and why of the crime, but also unsettled in regards of how one should respond. Should one feel sympathy towards the victims and repulsion towards the crafty cruelty of the perpetrator, or should one feel satisfied that hardened criminals untouchable by the law were finally caught up by justice?

Mixing the Detective Genre with the Fantastic

Another result of Christie’s use of the nursery rhyme to shape her narrative plot is a border crossing and blending of the detective genre with the fantastic. While the detective genre depends on the notion of rationality, the genre of the fantastic “relies heavily on the notions of the real and the imagery” (van der Beek 22), attributing causality to the supernatural. ATTWN certainly offers a rational explanation in the epilogue; but, in the words of van der Beek, the novel is also “predicated on the notion of fatality” (25). It employs themes and techniques which characterise the fantastic to play on the sense that the outcome was inevitable and predetermined by fate.

The sense of fatality derived from the plot controlled by an age-old nursery rhyme is further consolidated by other fantastical elements to create supernatural colourings and to suggest that what was occurring in Soldier Island was possibly divine intervention, punishing transgressors and redressing social injustice. Christie makes her characters debate among themselves whether they were experiencing “an Act of God” (79). Emily Brent interpreted it to be “the wrath of God” striking down sinners, while Justice Wargrave, without denying such a possibility, ironically pointed out that “Providence leaves the work of conviction and chastisement to us mortals” (80). Blore acknowledged his fear “of danger undefined and tinged with the supernatural” (198). Vera wondered whether “Absolute Justice” was being administered by “heavenly visitants” not “from this world at all,” whereas Lombard maintained his disbelief in the supernatural (210). The different outlooks of the characters, however, do not dispute but rather strengthen the supernatural tone of the plot.

Other structural and thematic designs further enhance it. Firstly, the advent of eschatological judgment was announced at the end of chapter one, just before the guests’ embarkment for Soldier Island, through the prophetic voice of an enigmatic old man: “Watch and pray. The day of judgment is at hand” (14). At the close of Chapter Two, the message of doom was confirmed by Emily Brent’s uncanny utterance of the words of the Bible from her own lips: “… The Lord is known by the judgment which he executeth; the wicked is snared in the work of his own hands. The wicked shall be turned into hell” (33), while the victims, including Brent herself, knew yet not that they had entered a death trap. Christie also made General Macarthur the one who comprehended the message, who awaited “the end” in submission and “blessed relief” (106).

A second narrative device which adds a supernatural element to the plot is the ghostly presence of the dead, which suggests that the murders could be their bitter revenge. Before Macarthur’s death, he saw his wife Leslie, whose lover he had murdered (107). Similarly, Emily Brent at her death heard the “stumbling footsteps of the drowned girl,” Beatrice Taylor, and smelled “a wet dank smell in her nostrils” (164). The accusing presence of Hugo was also constantly felt by Vera, and eventually condemned her to self-hanging (222). Christie does offer a rational explanation through Lombard that what they experienced was nothing but “conscience” (211); but the effect of a supernatural force that acted through human conscience is not diminished but even more strongly suggested.

Finally, Christie employed the description of natural forces to highlight the providential judgment theme. The tempestuous weather condition beyond human control not only served the absolutely necessary condition to enable the murder scheme to take place on an isolated island, it was also a symbol for the eschatological end in itself. As the dead body of General Macarthur, who was anticipating “the end,” was brought in, stormy wind and rain also broke loose simultaneously, signalling the arrival of judgment (120). The “hiss and roar” of the rain (120) and the howling of the wind “in shuddering gusts” (138) which “drove them mad” (175) embodied the “wrath of God” to strike down transgressors, which was foretold by Emily Brent earlier in the plot and which now came to be fulfilled.

In sum, the narrative plot tightly controlled by the nursery rhyme, coupled with multiple supernatural elements, creates in the novel a mysterious sense of fatality, as if suggesting that the event was ordained and approved by a supernatural higher order. But the certainty of such a notion is quickly cast into ambivalence when the novel’s characters are examined.

A Whodunit Novel without a Detective?

Character roles constitute the third aspect of the genre pattern apparently broken in this novel. Admittedly, a whodunit novel is almost by necessity narrative dominant and plot heavy, with a downplayed interest in its characters (Malmgren 121). In addition, characters serve the plot in that they play clearly defined roles such as the victim(s), the criminal(s) and the investigator(s). In ATTWN, however, the boundaries of these roles are completely erased. The perpetrator was a ghostly existence by the name U. N. Owen. All ten characters were at the same time crime suspects, murder victims, convicted killers of past crimes, as well as potentially the perpetrator of the crime currently being committed. As Justice Wargrave said, “Mr Owen is one of us” (Christie 123).

In the isolated world of Soldier Island, the identification of good and evil characters was made ambivalent because of the erasure of the boundary of their roles. Murder was conceived as a service of justice, killers became victims, and the murderer played detective and judge. Alison Light observes that in Christies novels the characters always come to alarming realisation that “it is people ‘one’ knows who are potentially murderous, … [a]nd it is not physical disguise so much as psychological disguise which is potentially pathological” (94). In ATTWN, where “every person is both a potential murderer and victim” (98), the fears about the precarious social fabric were amplified to the extreme.

What particularly calls for attention in the novel’s design of characters is the absence of a Poirot or Miss Marple type of detective. Police officers of Scotland Yard did make an appearance, but only in the Epilogue, and only serve the structural function of restating the pieces of the puzzle. They had no role in the narrative proper and offered no solution. Instead, investigation, interrogation and the deductive process, normally activities of the investigator as part of the genre’s features, are shared among the criminals and victims themselves.

For example, the physically active side of sleuthing such as searching the island was represented by Mr Blore and Philip Lombard. Mr Blore, the only professional detective supposedly hired by Mr Owen and the last character presented to complete chapter one turned out to be a “red herring” for the reader familiar with the mystery genre who would be expecting to find in him the typical investigator. But ironically Blore was a “fool” (116) for a detective, incompetent in hiding his identity, obtuse where evidence was obvious, and always wrong in his conclusions. Lombard, on the other hand, was shrewd and sharp in judging people and situations. He was the only one among the characters that intuitively correctly identified Mr Owen in Justice Wargrave, who played “God Almighty,” “Executioner and Judge Extraordinary” (140).

Nevertheless, it was Justice Wargrave, who “assumed command with the ease born of a long habit of authority” and “presided over the court” (122), that fulfilled the typical features of the detective figure of the mystery genre by demonstrating the conventional ratiocination, the examination of evidence and the method of elimination. In his words , “there can be no exceptions allowed on the score of character, position, or probability. What we must now examine is the possibility of eliminating one or more persons on the facts” (128; original emphases). Although, like a typical detective depending mainly on intellectual power, he “refrained from any overt activity” (122), he also ostensibly carried out disguised investigation through faking his own death, with Dr Armstrong playing his trusting assistant.

It is worth asking what effects Christie’s deconstruction of character roles, especially the elimination of the conventional detective, might have on the novel’s thematic development. According to Malmgren, mystery fiction “presupposes a centred world” (119) and its genre conventions serve the function of “the non-arbitrariness of the signs” of the world it reflects (120). It is the detective character such as Poirot that is tasked with the restoration of order and harmony after a crime was committed. Knight aptly observes that “the focus of a Christie book is often the personality and value of the detective,” who is “a powerful force for good” (90). The reader receives “the comfort of resolution” through the identification and elimination of the perpetrator by the detective (Kaplan 146). Or in Malmgren’s words, the detective such as Poirot in the whodunits “serves the deity that presides over the motivated worlds of mystery—the god of Order” (122). In ATTWN, however, such a presider over order and justice is absent, and the mass murderer acts as a god of cruel judgment. Although a perfect solution to the puzzle is offered, no comfort and satisfaction can be gained, and one is left to wonder where to place Justice Wargrave on the scale of good and evil.

Erased Boundaries between Victims and Villains

Indeed, the act of Justice Wargrave in the novel is full of ambivalence. Two somehow different pictures of his personality are given, one by the narrator throughout the story, and the other by Wargrave himself in the Epilogue that provides the solution to the puzzle. In Wargrave’s self-portrait, his motivation for committing a crime that no one could solve is explained plainly. He was fascinated with crime and punishment, possessed by both “a definite sadistic delight in seeing or causing death”—“the lust to kill,” and “a contradictory trait—a strong sense of justice” (Christie 237). Wargrave, in his own eyes, might be insane but not purely evil:

I wanted something theatrical, impossible!

I wanted to kill… Yes, I wanted to kill…

But—incongruous as it may seem to some—I was restrained and hampered by my innate sense of justice. The innocent must not suffer. (239)

Therefore he hunted down ten of those who had committed crimes but were untouchable by law, and executed his own justice:

Those whose guilt was the slightest should, I decided, pass out first, and not suffer the prolonged mental strain and fear that the more cold-blooded offenders were to suffer. (243)

But does his sense of justice have any validity at all? The portrait of Wargrave by the narrator strongly suggests a negative answer. He is singularly described as “malevolent,” “reptilian” (30), “cruel” and “predatory” (66), and unequivocally assessed to be a “madman” and “dangerous homicidal lunatic” (50), even “possessed by a devil” (124). Hence the perfect execution of his clever scheme is in no way conveyed as a carrying-out of justice, but a heinous crime. Indeed, he bore on his forehead the “brand of Cain” (249), the father of all murders in biblical genesis. The solution to the puzzle, then, offers no sense of a restoration of law and order, but a parade of the triumph of evil.

Yet the moral scale does not lean to the side of the victims either. The portrayals of the other characters hardly arouse sympathy in the reader. As mentioned earlier, conventions of the whodunit novel dictate that its central drama revolves around detection rather than complex characters. It has been noticed that generally in her novels

Christie carefully turns down the emotional temperature of the novels, aligning the readers’

identification not with characters at all but with the problem-solving pleasures of the sleuths. The whodunnits in general were distanced from the affect surrounding the dead bodies that so necessarily litter the genre. (Kaplan 146)

ATTWN conforms to these general patterns to a large extent in that the characters are “psychologically transparent” (Malmgren 121) and, although the conventional sleuth character is non-existent, the reader’s attention is drawn to the clues and the puzzle-solving process. However, three psychological traits are highlighted in the descriptions of the characters: callousness, fear and ferocity. Justice Wargrave aside, callousness is embodied by Emily Brent:

There was no self-reproach, no uneasiness in those eyes. They were hard and self-righteous. Emily Brent sat on the summit of Solider Island, encased in her own armour of virtue. (Christie 91)

In contrast to Emily Brent’s coldness is the “mortal fear” lived by Mrs Rogers, who “looks frightened of her own shadow” (25). Frightened yet ferocious is what the victims had in common when they realised that they were being hunted down one by one by one among them. They were “linked together by a mutual instinct of self-preservation” but there was no camaraderie, trust or sense of loyalty; they were “enemies” (174). Christie uses sustained animal metaphor to suggest her characters’ lack of humanity:

And all of them, suddenly, looked less like human beings. They were reverting to more bestial types. … Ex-Inspector Blore looked coarser and clumsier in build. His walk was that of a slow padding animal. His eyes were bloodshot. There was a look of mingled ferocity and stupidity about him. He was like a beast at bay ready to charge its pursuers. Philip Lombard’s senses seemed heightened, rather than diminished. … And he smiled often, his lips curling back from his long white teeth. (174–175)

If the murderer, Justice Wargrave, was a predatory reptile, his victims were equally ferocious and beastly. While Blore resembled “a wild boar ready to charge” (191), Lombard was repeatedly compared to a dangerous panther (33; 219), or a wolf that snarls and bares its white, pointed teeth (43; 149; 170; 189; 217).

Comparatively speaking, the most complex character is Vera Claythorne due to the fact that Christie used streams of consciousness to depict her psychological movements. Compared with the transparency of other characters, Vera’s outward appearance and inward state were more incongruous. Externally she appeared to be shocked by Lombard’s crime of abandoning his native followers to a death of starvation (55), but inwardly she laughed at the idea that the natives were “our black brothers” (89). Outwardly she appeared pitiable, like a “dazed” bird that was “terrified, unable to move, hoping to save itself by its immobility” (175), but inwardly she was really “a cool customer … and one who could hold her own—in love or war” (5). Her true character was borne out by the fact that she even deceived and killed Lombard, the sly and dangerous beast of prey. That she was the last to die by self-hanging according to Wargrave’s scheme also testified that her crime was judged to be the most cold-blooded offence of all.

With no protagonist detective to restore law and order, with all victims almost without exception appearing to be unworthy of sympathy but rather deserving punishment, and with a perfect crime that could not be solved designed by a mastermind who was the mockery of justice, Christie designed characters in the novel that deviated from familiar patterns of the mystery genre. This formal innovation created in effect thematic complexities, casting much ambivalence upon questions such as whether individuals have the right to take the law into their own hands, whether “an eye for an eye” revenge has moral basis, whether one has the right to play judge on fellow human beings, whether justice is true justice without mercy, and so on.

To conclude, in her popular novel, And Then There Were None, Agatha Christie flouts many rules of the golden age whodunit fiction in terms of the story’s setting, plot and character roles, although what she does was “a playful deconstruction rather than wholesale destruction” (Makinen 417). What is demonstrated is not only intelligent manipulation of genre conventions; more importantly, through critical engagement with the genre form, Christie has created thematic nuances that force the reader out of the escapist comfort zone—which many critics have labelled whodunit fictions to be, and presented serious challenges related to the social reality of crime and punishment, as well as complex moral issues involved in carrying out justice.

Works Cited

Christie, Agatha. And Then There Were None. Harper Collins, 2015.

Kaplan, Cora. “Chapter 8: ‘Queens of Crime’: The ‘Golden Age’ of Crime Fiction.” The History of British Women’s Writing. Volume 8, 1920-1945, edited by Maroula Joannou. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, pp. 144–57.

Knight, Stephen. Crime Fiction: Detection, Death, Diversity. Palgrave, 2004.

Light, Alison. “Chapter 2: Agatha Christie and Conservative Modernity.” Forever England: Femininity, Literature and Conservatism between the Wars. Routledge, 1991, pp. 61–113.

Makinen, Meria. “Chapter 33: Agatha Christie (1890–1976).” A Companion to Crime Fiction, edited by Charles J. Rzepka and Lee Horsley. Blackwell, 2010, pp. 415–426.

Malmgren, Carl D. “Anatomy of Murder: Mystery, Detection, and Crime Fiction.” Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 30, no. 4, 1997, pp. 115–135.

Pyrhönen, Heta. “Chapter 3: Criticism and Theory.” A Companion to Crime Fiction, edited by Charles J. Rzepka and Lee Horsley. Blackwell, 2010, pp. 43–56.

Todorov, Tzvetan. “Chapter 3: The Typology of Detective Fiction.” The Poetics of Prose. Blackwell, 1977, pp. 42–52.

van der Beek, Suzanne. “Agatha Christie and the Fantastic Detective Story.” CLUES: A Journal of Detection, vol. 34, no. 1, 2016, pp. 22–30.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Interesting article! Agatha Christie has such a huge impact on the mystery genre, and it is always valuable to examine her novels more closely!

Yes, I’m glad you think so too. The ways she manipulates the genre to become its master are fascinating.

I like her characters. It’s perhaps a bit much to say that they’re well fleshed out – they are a teeny bit cartoonish – but they’re very appealing cartoons.

To stretch the metaphor a little – it might be observed that some cartoonists are a little better at capturing the significance of a person than an oil painter.

A good article, this.

Point taken 😀

But to be fair, the mystery genre is almost by definition strong on plot and weak on characters – except the detective of course; and ATTWN has broken even that rule by having no detective!

I read this book as a teenager, and I couldn’t understand what it meant by “very modern” house. I kept imagining a super minimalist 1980s geometrical monstrosity of white stucco and chrome, which i knew couldn’t be true, but I didnt understand what modern meant for the 1930s.

I don’t know if teenage you would have been exposed to Art Deco and Art Moderne.

And we do picture the houses and architecture of our time when we read Christie – perhaps more than her time.

2015 ultimately falls victim to writing for millennial & genz audience who resist nuance, subtlety, shades of Grey. It’s sad, really. They miss a lot.

The Russian version is very good, as long as you have subtitles, or speak Russian!

The 90 minute BBC radio adaptation is good too!

While I love the 2015 version, I absolutely hate that they took out the passive murders. The fact they all were involved with deaths that would he hard to punish them for is the entire point of the book. The style and actors chosen for the 2015 version were excellent

Trouble with adapting this book is that it’s so iconic, I imagine most people have read it. Knowing the plot is surely gonna ruin any suspense, especially the jaw dropping WTF? at the end.

You must not be a true Agatha Christie fan. Being one I can tell you that it never gets old seeing her work adapted. Also, she’s the best selling novelist of all time (outsold only by the Bible and Shakespeare) I can gaurentee you the rest of her fan base is looking forward to any adaptations of ATTWN.

I usually avoid Agatha Christie adaptations, since I don’t think she’s anywhere as a good a writer as Dorothy L. Sayers. But this article has piqued my curiosity.

I like Allingham myself. Sayers is a terrific writer, who is great at fleshing out her books but Lord Peter annoys me. At least Campion is funny.

Not sure that really makes a lot of sense. No matter how poor a writer she may or may not be adaptations must surely be taken on their own merits as the product of their writers not Christie herself?

It makes me less inclined to watch the adaptation if I’m not impressed by the original text, since it’s the basis for the adaptation. And I’m much more interested in the characters than whodunnit, so that makes Christie even less appealing.

I’m probably the only person who thinks this but my favourite of hers is ‘They came to Baghdad’; it’s not clever or ingenious like ‘Then there were none’ or ‘Murder on the Orient Express’ but its one I can happily reread on a lazy Sunday afternoon and Victoria Jones is such a modern and well rounded female character that it’s hard to think it was written in the 1950s by a woman who was born when Victoria was on the throne.

You are not the only one! My favourite as well, and for the same reason.

For me, the best Agatha Christie is “Crooked House”, closely followed by “Ordeal by Innocence”. She was a master at capturing the seamy underside of families. The best book written by Agatha Christie, was, in my humble opinion, “Absent in the Spring” published under her pseudonym of Mary Westmacott.

Absent in the Spring is excellent. I’d also put a vote in for The Hollow.

Agreed! it was by far the best Poirot. Who could forget the memorable description of the luncheon roast in the oven…? It also strips away the sentimentality of families, to reveal something rotten. Yes, it is an excellent book, but there is something especially chilling (and perfectly constructed) about “Crooked House” where we, the readers, “know” the resolution, but are not prepared to admit it to ourselves, that puts it at the top of my list.

My favourite is the one with the alien wasp and the two time travellers.

The Russian film version which, unlike any of the others, stays faithful to the book’s ending can be found on YouTube (if you don’t mind subtitles).

I can read this novel over and over without its atmosphere ever diminishing. As regards the plot, the only death I would have an issue with is when Wargrave is shot. There’s just not time for him to be placed in the chair and all the paraphernalia attached to him.

The “Family Guy” version is great fun!

I can’t explain at all. I’ve read them since I was a kid and keep thinking they won’t be that good when I find another I’ve not read – but I always enjoy them.

No great mystery, really, though – some people like them, some don’t. But trying yet another when you hated the first is a waste of time.

Five Litlle Pigs – where a murder has been committed many years previously – is one of the very best. Each character/suspect is visited again and forced to recall the same past events in detail.

Best plot is definitely Death on the Nile – however hilarious the charcters like the stock drunk novelist and undercover Marxist aristocrat, the solution still stands up as one of the most ingenious murder mysrey plots ever.

I read the book this summer and found it a huge let-down. I know it’s sold millions of copies but why isn’t clear. For starters, it’s really short and can be read in a single sitting. This is probably due to the miserably poor characterisation and clipped dialogue. Sure the plot is ingenious but it is not, repeat not, creepy or frightening at all.

Showing my age.

But I read the book with its original title.

Then it was changed because the title was racist.

Then changed again for the same reason!!

I still remember it. I took that book from the library, went home, made a cup of tea and sat under the lamp intending to read a chapter or two and then go to bed…six hours later, I was still in that chair with a cold cup of tea on the table, reading the penultimate chapter and starting to believe the old bat actually wrote a supernatural novel.

And then came that last chapter.

Indeed, AC’s satanic streak will haunt me forever. One of my favorite thrillers ever.

And Then There Were None has got to be one of the most boring mystery novels out there. This is nothing again Christie…I am a massive fan of most of her novels.

Fantastic article! It was a pleasure to edit, and I loved the way you analyze Agatha Christie’s work! It’s wonderful to see this on the site. Great job!

😊 You are so kind – thank you for your helpful feedback!

Thank you for the compliment! I’m happy to know that you found my feedback helpful! Looking forward to your next article!

And Then There Were None is too improbable.

This is one of the strongest books, not only as a mystery, but as a psychological study & a moral debate. None of the adaptations I’ve seen really get it, imo. Turning indirect, moral guilt, into actual murders undermines the entire idea & makes it less thought-provoking. Just like turning some of the characters into good guys & letting them survive.

While I love the 2015 version, I absolutely hate that they took out the passive murders. The fact they all were involved with deaths that would he hard to punish them for is the entire point of the book. The style and actors chosen for the 2015 version were excellent.

I wonder if the 2015 miniseries is making a point about privilege and who we believe. Even though they are guilty, they would’ve still been able to escape justice.

Watched 1974 last night and it is easily the worst adaptation of ANY book I’ve ever seen.

It fails on so many levels, and the changes feel at first unnecessary but end up having enormous consequences.

The hotel is so big it would be impossible to check every room so they can’t be certain they are alone. There’s also no reason why they couldn’t just split up, hide, and barricade themselves in random rooms to try and wait out the murderer.

The changing of the crimes seems pointless but ends up changing the motivation and sympathies towards certain characters. Vera and Hugh actually being innocent is ridiculous and goes against the central premise of the book, they then have to change the ending to counter this which is even worse. A small change causes them to change the entire plot.

The poem, there is close to no attempt to stick to the poem and ones like #6 bee sting easily COULD have been changed to snake bite but they were too lazy. #9 and #8 are so different from the poem that really you wouldn’t be able to figure out what is happening.

There’s minimal discussion about the gun, there’s never an attempt to confiscate it and it never goes missing and reappears.

Dialogue. There’s very little ‘strategising’ outside of a few lines between the judge and doctor. They briefly try barricading themselves in their rooms but Hugh immediately abandons that to see Vera (stupid) and when they hear a noise he bangs on Blore’s door with a gun in his hand who for some reason trusts and follows him (why would he do this?). There are very few moments of accusation, the murder method for #9 being changed means there’s no longer a reason to suspect the doctor, #8 gets sabotaged so again anyone could do it rather than who was without alibi/best opportunity.

Awful awful awful film. I can’t believe the GAUL to read the 6th best selling book OF ALL TIME and think ‘yes, I could do a better job of this than Agatha Christie and I will therefore change nearly everything’

2015 could have been perfect if the murders had have been passive ones like the novel.

The films that use the original story (not the stage version), even the 2015 version, are not totally accurate to the way the murderer kills himself. Christie was so specific. I wish someone would do it like it is written.

To be honest, the 2015 version’s way of murderer killing himself is closer to the book. In 1987’s they just shot themself, not leaving a mystery for the police

Only seen 1945, 1974 and the 1989 versions, all enjoyable. I have a bias towards the 1974 version as I saw it first and it is oddly a sort of comfort film. the 1989 version is….odd, though the location I liked enough for being different, though the film felt less like well a film and more an extended version or a weaker Murder She Wrote episode. I do want to see the other versions.

Love 1945 adaptation. Love 2015 adaptation, which I bought for Aidan Turner.

There was a quite recent episode of Masterpiece Mystery Endeavor that reminded me greatly of “And Then There Were None”.

I have a problem with old movies. I think they overact with mean looks all the time. And the music is too much too. I can’t get involved, it makes me laugh.

There is an excellent French mini series THE CHALET released in 2018 that is also loosely based on this premise.

I think the original ending was brilliant and perfect. For me, if I hear the ending was changed, personally, then the adaptation of this book in particular goes down in my view. I know that is unfair, but the original ending is just that good.

I love the book, and I love the 2015 adaptation.

Few novels have survived–a pointedly chose verb–the test of time as this one has and will continue to do so. Its rhythmic pacing in the disposal of life’s well-heeled detritus continues to confound those who believe in justice for those who have escaped judgment—or so it would seem.

Great discussion, I’ve not read this one yet, but will be chasing it down. Christie really did some interesting things in her work, beyond the Pirot that she is most known for she really did experiment with form and style a lot.