Are Fossils the New Art? Analyzing the Lords of the Land Gallery

French art collectors Mr. And Mrs. Ommeslaghe distinguished between artwork and decorative objects in an interview included in the German documentary Beltracchi: The Art of Forgery (2014). They exemplified their definition of artwork with the pieces by Andy Warhol, René Magritte, and Heinrich Campendonk that hung behind them in the sitting room. Decorative objects, they agreed, were less valuable, even less authentic; the photographs in her dressing room for example, or the Japanese cloisonné vases under the Matisse drawing. Their description illustrates how the empirical worth assigned to artworks in the international market (translated in the dollar amount payed by the last owner) is the result of a series of subjective interpretations.

These individual assessments are often influenced by geopolitical values. Prevalent patriarchal attitudes in 20th century western society, for example, contributed to the traditional exclusion of female visual artists from important North American and European exhibition venues. Museums, galleries and auction houses choose what to display based on considerations that often have little to do with the perceived quality of an artwork. Government agencies fund exhibitions that can advance, or at least not challenge, their own political and economic objectives. Commercial galleries shy away from artists who explore controversial themes such race, politics, sex and religion, for fear of alienating patrons. The result is an orthodox art world, where everyone who is anyone collects the same artists (mostly men, mostly European and North American), while excluding entire geographical regions, mediums and cultures from having their own cultural production recognized as art. So what happens when the Royal Tyrell Museum in Drumheller, the only museum dedicated to paleontology in Canada, decides to display fossils as artworks in one of its galleries? How does their explicit comparison of fossils to internationally recognized masterworks disrupt traditional conceptualizations and valuations of art?

Paleontology is the study of life on planet Earth before the Holocene, a geological epoch that began approximately eleven thousand years ago. Fossil rich-areas, like the Canadian Badlands in the province of Alberta, are also rich in fossil fuels such as coal, natural gas, and oil. During the first two decades of the 20th century, the Badlands, and especially the town of Drumheller, experienced an economic surge spurred by the sale of fossils to internationally recognized museums. The National History Museum in London, and the American Museum of Natural History in New York, both purchased dinosaur fossils from Alberta during this Great Canadian Dinosaur Rush. Fossils continued to be at the centre of the social, politic and economic activity of the area when the rush ended. Starting in the 1930s, Drumheller alone produced over two million tons of coal yearly, and employed more than 2000 miners in the Badlands coal mines. This bonanza ended in the 1950s, when oil and natural gas were produced for the first time in Leduc, another Alberta town, which caused the coal production to decline until only abandoned mines and towns dotted the striking Dinosaur Valley landscape.

Photo by Ana Ruiz, 2016.

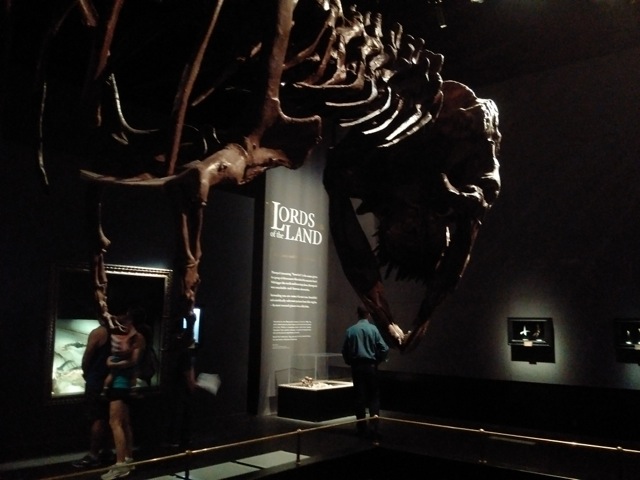

The Royal Tyrell Museum opened its doors to the public in 1985. The province of Alberta invested thirty million dollars in the project, the equivalent of sixty million dollars today, with the objective of economically mobilizing the historical fossil resources of the region. Four hundred thousand people from all over the world visit the Royal Tyrell every year; if all visitors paid the same amount I did in June 2016, the museum’s yearly ticket sales total more than 8 million dollars. But that is only an added benefit. The Royal Tyrell’s main contribution to the provincial economy is increasing the value of local resources through the value-added economics of research and display. Lords of the Land, a small gallery within the gargantuan 4,000 square meters of exhibition space at the Royal Tyrell Museum, illustrates this dynamic through their curatorial framing of dinosaur fossils as artwork.

Photo by Ana Ruiz, 2016.

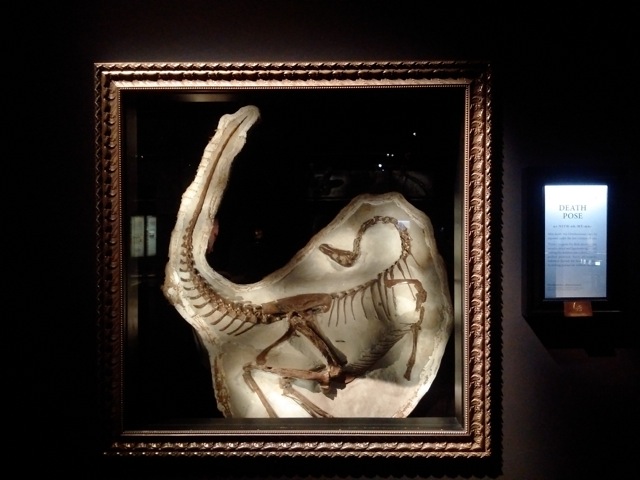

Classical music salutes the visitor’s entry into Lords of the Land. The walls are painted in a stark dark grey colour, providing a point of contrast to the dramatic lighting and the gilded frames that contain dinosaur fossils in impossibly stylized postures. This small gallery displays some of the rarest and most scientifically important pieces in the museum’s collection, including a three-dimensional, full reconstruction of a Tyranosaurus-Rex. The way these pieces are exhibited however, is the really interesting part. These crown jewels of the Royal Tyrell are presented to the audience as visual art masterpieces by employing the aesthetic signifiers of the modern museum. The holotype of Atrociraptor marshalli is displayed inside an ornate gilded frame, and the skeletons of raptors are placed atop high white pedestals, dramatically lit. The interpretive signs emphasize aesthetic vocabulary: elegant, captivating, dramatic.

Photo by Ana Ruiz, 2016.

Photo by Ana Ruiz, 2016.

Lords of the Land is the only gallery within the Royal Tyrell that proposes this interpretation of fossils as art; the rest of the museum’s displays utilize a less dramatic, more didactic approach to exhibition. This gallery not only increases the value of local economic resources like fossils, but also challenges current definitions of art. Its curatorial argument – namely, that a restored T-Rex skeleton is as valuable, rare and aesthetically pleasing, as Leonardo DaVinci’s Mona Lisa (1503-1517) – increases the prestige of the Royal Tyrell and the value of its collection. The linkages established in Lords of the Land between traditional conceptualizations of artwork, fossils and the politics of display are groundbreaking in Canada. Galleries like Lords of the Land outline contested definitions of art that modern commercial galleries and established museums rarely address. Walking out of the dimly lit gallery I imagined my own living room, decorated with white lace-like skulls instead of oils on canvas. It looked beautiful, and it made me wonder if one day, Mr. And Mrs. Ommeslaghe would trade in their Campendonk for a Velociraptor.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The Black Beauty Dinosaur skeleton is particularly amazing.

Extinct species as art. Only by humans. 🙂

Art is subjective.

Interesting article. Fossil is the new art. It wasn’t long since I was there. I was surprised by the size of the exhibits and the depth of information available.

I have loved this place since I was a kid. There is so much to see and even though I have seen the museum several times, for me it never grows boring.

It was interesting seeing how many have been discovered recently.

They really celebrate palaeontology, and don’t just make a flashy tourist trap.

I really like the way this article is written. Aditionally, I think that the Royal Tyrell Museum should be applauded for the way it emphasizes fossils as artwork. From what I can tell, the museum strives to celebrate history as much as your typical “oil on canvas” artwork is. This is so important because it is these fossils that have given insight and key knowledge to how humans/Earth evolved!

Suppose this meant other objects could be considered artwork. A gilded frame and some Shostakovitch bounding a polar bear exhibit in a zoo? Does art need to be inert or can it still be living while we increase it’s value?

Other objects should be considered artwork in order to be inclusive. Reducing the worth of artwork to economics (how much someone would pay for it) is a disservice to the social role of art; unfortunately, this is a position that is widely adopted in North America and Europe. However, this economic valorization is not universal and it should not be treated as such. In Latin America for example, the artist traditionally fulfills a social role of information and debate, and his/her work is understood in terms of the ideas contained in it, and not stylistic concerns which, after all, were mandated by the international market.

Fascinating! Definitely worth the trip.

I visited this museum recently. Exhaustive amount of information, clean, quality displays. My only complaint was it was packed. Every area of the museum was congested with visitors.

Real fossil country there.

You did a fantastic job with this topic.

thank you! I really appreciate that.

The Royal Tyrrel Museum is definitely one of the Museums that I WILL visit before I die.

I’ve visited the museum several times, mostly as a child who had lived near the area, and I never considered the possibility of the fossils as art. This article was interesting because it cast a new artistic appreciation, at least for me, on the exhibitions.

“Government agencies fund exhibitions that can advance, or at least not challenge, their own political and economic objectives.”

Being that fossils often appear amidst energy resources, such museum exhibitions provide an invaluable service probably against a certain amount of oil-money resistance.

Ms. Ruiz: You hit on a lot of current contemporary aesthetics debates in this well-written article. The title is, certainly, supposed to grab attention, but in answer to it I say: sure! Then again, in answer to it, I say: no! This is the glorious nature of contemporary art today. We don’t have to “choose” whether something is art or not, if we don’t want to. We don’t have to bow down to the “sensus communis” if we don’t want to. Found objects, conceptual art, political art, folk art: all these are valid genres for art. The problem most people have is not this destruction of the “canon,” so much (I don’t know. Maybe they do), but one of aesthetic judgment, which hearkens back to – yep – Kant. People feel queasy when they cannot neatly put one thing or another into a container, stored away in the brain, and give it a grade. Well, I understand. I am not one who thinks that “all art is good” or “everything is art” or “art is whatever you want it to be.” However, your point is well taken. Art, as has been established, historically have used aesthetics “metrics” that are not aesthetically-based: how much money it can get, who your patron is, your gender or lineage, etc. At the same time, the art that exists before shouldn’t be condemned. How can one condemn Rembrandt? Alternatively, not ALL conceptual or found art I think should be instituted as the “new thing.” However, the fossil show looks beautiful. Wonderful. It reminds me of Mark Dion’s work. I wonder: is it something related to Duchamp? Is it beautiful, not because of its mere material beauty and age, but because it was purposefully chosen, buffed, framed, and curatorially organized? I don’t know. I will never know. In fact, even though I enjoy asking these questions, I enjoy the not-knowing. Looking at art gives me joy. I believe to be discerning, but again – who knows? I don’t care. I shall continue to search, ask, look, and marvel, and how wondrously full life and art are.