Novels and the Battle of Gettysburg: Fiction Enriches History

The Battle of Gettysburg (Pennsylvania, July 1-3, 1863) during the American Civil War (1861-1865) is often cited as one of those moments in American history that just capture a certain imagination. In 1990, Congress created the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission (CWSAC) which listed 384 principal Civil War battle sites. Among those battlefield sites, Gettysburg is a favorite destination for visitors. The battle itself was enormous in size with 170,000 troops involved. After Confederate General Robert E. Lee withdrew his Army of Northern Virginia, the South never again seriously threatened on Northern soil.

Is it known at the time that a battle is considered a turning point in a war? Military historians, John Keegan for one, raises that issue and questions whether a specific battle can be seen as a turning point in a war. 1 The day after the Battle of Gettysburg ended, Vicksburg (Mississippi, May 18–July 4, 1863) fell to Union forces under Major General Ulysses S. Grant. Within a week of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Confederate forces at Port Hudson (Louisiana, May 21–July 9, 1863) surrendered to Major General Nathaniel Banks. Victories at Vicksburg and Port Hudson meant Union forces now had complete control of the Mississippi River: Two Union wins along the Mississippi River, increased the significance of Gettysburg. Taken together, the three Union victories close together galvanized Northern support for the war effort which, even a month earlier, was at a low point. In addition, President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, some four months after the battle ended (November 19, 1863) added to the importance of Gettysburg.

After Confederate General Robert E. Lee, Commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, decided to not continue his assault as the fighting ended on July 3rd, it is doubtful that participants on either side were thinking about their places in history. One historian writing on this battle wrote, “I became fascinated as much by the manner in which Americans distort and reshape the history of Gettysburg, as with discovering the truth about the battle.” 2 Gettysburg carries images and meanings and those images and meanings have changed with time, and it can be assumed that what is taken away from this battle will continue to change.

The issue of the reshaping of history is important to this essay which addresses two novels written about the Battle of Gettysburg. Michael Shaara’s, The Killer Angels: A Novel, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1975. Shaara’s novel elevated Colonel Joshua Chamberlain to the level of a major figure in the Civil War. 3 Chamberlain commanded the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment and this regiment played a significant role in the second day of fighting around the area known as Little Round Top. In April 1865, by then a Brevet Major General, he was given the honor of leading Union troops as Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House (Virginia). He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his action on the second day of fighting at Gettysburg. President Donald Trump signed an executive order to create a new park with statues of thirty “American heroes.” One of the thirty named heroes listed on this executive order is Joshua Chamberlain. 4

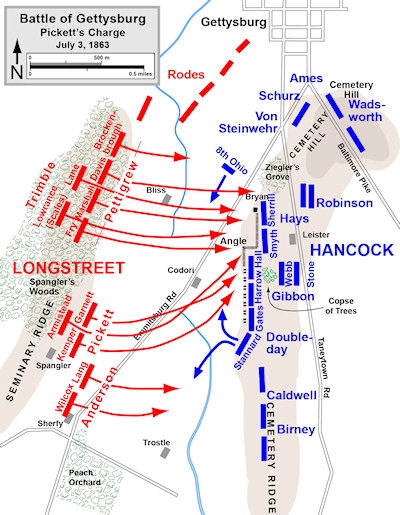

The second novel is an interesting “what if” novel that ends with Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia winning the Battle of Gettysburg. Newt Gingrich and William Forstchen in Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War, have Lt. General James Longstreet, who was Lee’s second in command, propose a plan that involved more maneuvering, which runs contrary to Lee’s natural inclination to have gone on the offensive. The rank of Lt. General was introduced earlier in the Confederate Army than the Union Army: Grant was the first Union General to achieve the rank of Lt. General in 1864. 5 This novel is part of a trilogy of Civil War novels written by Gingrich and Forstchen. Gettysburg: A Novel is the first in the trilogy and is addressed here without reference to the other two novels. The other two novels in this trilogy continue the story after Gettysburg. 6

Significant transformations have taken place in the study of the Civil War since the days after the war ended when the history of this period was confined almost entirely to white Southerners. Many of those writers carried with them the scars of the war and that affected how they wrote about it—often in incredibly one-sided ways. Scholarship that is addressed by many fine books and professional journals show the changes that have taken place in the serious study of the Civil War

There are historians, as well as history buffs, who have studied specific battles. The strategies and tactics associated with different Civil War battles separated from broader issues about the Civil War and their impact on subsequent postwar developments, serve to highlight that the outcome of the war was not a forgone conclusion. The two novels discussed in this essay add to how the Battle of Gettysburg, specifically, is studied.

Leadership of military units can be studied within this approach to Civil War history. Basic to this approach to studying Civil War battles is understanding how the armies were organized. The armies on both sides were broken down as follows: An infantry company of approximately 100 soldiers, was the basic unit; approximately ten companies made up a regiment with four regiments creating a brigade; a division could be made up of approximately three brigades; usually three divisions made up a corps, and; an army was then made up several corps, the exact number could vary. The cavalry and artillery were also organized into units. 7

In addition to the scholarship that exists, and continues to be written, there is the professional military use of staff rides. Staff rides are situations where military students, and oftentimes officers who are attending war colleges (such as the Army War College at Carlisle, Pennsylvania) are taken to actual battlefields to understand terrain, as well as communication between and among different military units, such as corps commanders issuing orders to division commanders, or division commanders issuing orders to brigade commanders. One of the lessons that it is hoped will be learned from this exercise, is to better appreciate the “fog of war.” This term has been popularized in association with Karl von Clausewitz (1780-1831), although he never actually used that term. Clausewitz was a Prussian military officer who drew upon his involvement in the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) to write about military strategy. The expression fog of war refers to the inevitable confusion, uncertainty, and misinterpretation of orders that will happen once actual combat begins. Gettysburg is a site of frequent staff rides. In fact, in the Gingrich and Forstchen novel, it is noted that one of the authors (assumed to be Gingrich) went on a staff ride as preparation for writing their novel. 8

The Civil War is not just History, but Matters Now

James McPherson, a well-known Civil War historian, referred to the “open questions” that are still with us today which did not end with the fighting. 9 The issue of what to do about Civil War monuments indicates that the past is not dead but matters now. In addition, “The Lost Cause,” which gained popularity immediately after the war ended in 1865, is still very much alive and well today: Gettysburg plays a pivotal role in the sentiment and thinking surrounding the belief in this cause. The Lost Cause belief, was best developed by a Virginia journalist, Edward Alfred Pollard, beginning in 1859, before the Civil War. After the war, it was expanded on and widely accepted throughout the South and, in many ways, by some Northerners as the 19th Century came to an end. At Princeton University (the College of New Jersey changed its name to Princeton University in 1896) the Lost Cause sentiment took on a nostalgic feeling. One writer wrote that Princeton undergraduates began to embrace the Lost Cause thinking as a “romantic vogue,” and created a Southern Club in 1888. 10 In 1866, Pollard wrote:

No one can read aright the history of America, unless in the light of a North and a South. [For all its bloodshed, the Civil War] did not decide negro equality; it did not decide negro suffrage; it did not decide State Rights. … And these things which the war did not decide, the Southern people will still cling to, still claim and still assert them in their rights and views. 11

The assertion that the South was on the side of righteousness is basic to Lost Cause sentiment: This sentiment has been closely tied to Gettysburg. Fighting at Gettysburg, whether focusing on a particular place within the battlefield or focusing on a specific individual it is believed, made all the difference between the Confederacy winning and losing the battle or even, more broadly, the war. Lost Cause thinking magnified what happened at Gettysburg and is one of the reasons for continued interest in this battle.

This is a war that is far from over, it continues to exist in NASCAR’s decision to ban the Confederate flag or in a proposal to remove Robert E. Lee’s name from his house that overlooks Arlington National Cemetery, or the removal of the Confederate flag from its place on the Alabama state flag. Confederate Memorial Day is still a state holiday in several states: For example, Tennessee calls it Confederate Decoration Day and Texas calls it Confederate Heroes Day. 12 Several Southern states still observe Robert E. Lee Day as an official state holiday.

Tennessee, in 2019, created Nathan Bedford Forrest Day, who served as a Lt. General in the Confederate Army. Forrest was in command of Confederate forces that captured Fort Pillow, Tennessee (April 1864). Some 300-500 Union troops, many of them black, were killed by Confederates who refused to accept their surrender: Many of those killed were shot at point blank range. 13 Forrest wrote soon after this massacre the following:

The river was dyed with the blood of the slaughtered for two hundred yards. The approximate loss was upward of five hundred killed, but few of the officers escaping. My loss was about twenty killed. It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners. 14

The Union commanding officer of the U.S.S. Silver Cloud who arrived at the fort two days after the killing wrote about his interview with survivors:

[A]fter the fort was taken an indiscriminate slaughter of our troops was carried on by the enemy with a furious and vindictive savageness which was never equaled by the most merciless of the Indian tribes. Around on every side horrible testimony to the truth of this statement could be seen. Bodies with gaping wounds, some bayoneted through the eyes, some with skulls beaten through, others with hideous wounds as if their bowels had been ripped open with bowie-knives, plainly told that but little quarter was shown to our troops. 15

After the war, Forrest became the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. One of the original founders of the KKK stated, “after the order grew to large numbers we found it necessary to have someone of large experience to command. We chose General Forrest.” 16 Forrest either seemed to become concerned about excessive violence by the Klan and tried to disband it in 1869 or he felt the Klan had achieved its goals and could disband. Choosing which reason to disband the Klan, depends on how one wants to see this man now.

There are supporters of Forrest today who like to point to him as someone who changed his attitude toward race relations several years after the war ended. 17 Forrest, however, defended the creation of the Klan because, to use his word, the former slaves became “insolent,” in other words, rude. In addition, Forrest expressed concern about the need to find laborers to work the fields in the South after the war and his proposal was to send slave ships back to Africa. As Forrest put it, regarding using Africans as field hands, “[They are] the most imitative creatures in the world, and if you put them in squads of ten, with one experienced leader in each squad, they soon will revive our country.” 18 In creating a day for Forrest, Governor Bill Lee (Republican) stated, “I signed the bill because the law requires that I do that and I haven’t looked at changing that law.” Lee may want a rationalization to justify his action for creating a day to honor Forrest, it is doubtful that his statement absolved him of any responsibility for his action. 19

In discussing these two novels on the Battle of Gettysburg, the specifics, detached from broader Civil War issues and the concerns that followed the end of the war, can be discussed. Fiction, as addressed in these two novels, not primary documents such as diaries from Civil War combatants, or respectable histories, provide a way to look at aspects of this battle that can provide different perspectives: Fiction can enrich the study of history. Novelists can add drama and human emotion which may not be conveyed well through historical accounts of battles. Novels can provide conversations that may reflect how battlefield participants were thinking, which, again, may not be possible with accounts of specific battles.

Novels, when contrasted with how history examines a battle provide a means to understand that outcomes were not predetermined. The outcome is known, when studying an historical event and a novelist can help to put some of that thinking in check to place the reader in the thick of developing events. Two different types of novels about the Battle of Gettysburg, one which focuses on the actual events and one which addresses hypothetical developments, taken together, provide a means to study the battle itself but in ways which history alone cannot.

To appreciate these novels, it is necessary to examine historical developments related to the Battle of Gettysburg. Reading these novels, detached from a study of history, can diminish the use of them. Certainly, there are readers who are just interested in the novels themselves but the authors wrote them with a firm understanding of this battle as well as of the major participants. Readers of these novels can better appreciate them if they have a grasp of the history associated behind them. While fiction can enrich the study of history, history can help to develop a deeper appreciation for the fiction that this battle inspired.

Certainly, there are novels on the Civil War that address the anguish that families experienced, separated from the war around them. Or there are novels that focus on the political maneuverings that mattered to the conduct of the war. Furthermore, there are novels that focus on specific individuals and how the war affected them. But the two novels discussed in this essay are focused on a battle. Studying these novels, while addressing the actual battle, augments both the fiction created in them and the actual history of the battle.

Why Gettysburg Matters: Casualty Numbers

The Battle of Antietam (Maryland, September 17, 182) led to 23,000 dead, wounded or missing for both Union and Confederate forces: Four times more than American dead and wounded on D-Day (June 6, 1944). 20 Antietam was a one-day battle, that is broken down into morning, midday and afternoon parts for the sake of analysis.

The three days of Gettysburg rank it as having the highest casualty count of any Civil War battle, which included dead, wounded, and then the issue of later dying from wounds, and missing. Approximately 51,000 casualties, included some 10,0000 dead. In comparison, the Battle of Chickamauga (Georgia, September 19-20, 1863) had approximately 36,600 casualties, which is second on this morbid list. 21 Just by the sheer number of casualties, Gettysburg certainly deserves the attention it receives.

Casualty figures paint a picture of incredible devastation. For the North, approximately 2.1–2.5 million men served during the war with about 1 out of every 3 killed, wounded, captured or missing. There were some 2.4 million more men who could have served the North but did not. 22 In the case of the South, basically every able-bodied man served (750,000–1 million)—there were no reserves to call upon. For the Confederacy, the percentage killed, wounded, captured, or missing was approximately 65–80 percent of the total who served. The percentage killed, wounded, or missing, however, depended upon accurate counting, which did not appear to be possible. What is apparent, despite how inaccurate the count for dead, wounded, and missing, is that the Confederate losses sustained at Gettysburg were difficult to recover from for the South. 23

Counting dead, wounded, and missing was not an exacting process. Again, these figures for total dead, wounded, and missing are just estimates and the higher the figure goes, the worse for the Confederacy it looks. J. David Hacker, a researcher who studied census data, has placed figures for dead as approaching 720,000 or even higher–which contrasted with the 620,000-700,000 range that was accepted for years after the Civil War ended. Hacker actually has a range of 650,000-850,000 dead: A 200,000 count difference between his low and high estimates, gives a sense of the difficulty of counting the dead. 24

The Confederate death count was probably more inaccurate than the Union one. After the war ended in 1865, more than 100,000 Union corpses were found in the South and reinterred to Northern cemeteries. Of the approximately 2.1–2.5 million Union soldiers who served, about 180,000 were African American: 40,000 of them died, some 30,000 of those deaths were from disease and infection, the rest from combat. Some 100,000 deaths on both sides were because of dysentery: Lack of sanitation and contaminated water were a problem. 25 Generally speaking, for every Union death, there were three Confederate ones. As stated by Hacker:

It’s probably shocking to most people today that neither army felt any moral obligation to count and name the dead or to notify survivors. About half the men killed in battles were buried without identification. Most records were geared toward determining troop strength. 26

Clara Barton played a significant role in documenting many of the missing. In 1869, on a visit to Switzerland, she was introduced to individuals associated with the International Red Cross: She became the first President of the American Red Cross in 1881. Based on a letter she wrote to Lincoln in February 1865; she became head of what was known as the Missing Soldier Office. In her final report to Congress in 1868, she wrote that she had received 63,182 inquiries about missing soldiers and identified 22,000. 27

The flanking action that Gingrich and Forstchen have Longstreet propose to Lee, made complete sense, as a means of keeping Confederate casualty numbers down. Although their book is titled Gettysburg: A Novel, the battle as it unfolded, takes place some 16 miles from Gettysburg. Gingrich and Forstchen present Lee as able to overcome his personality faults, Shaara shows Lee at his worse.

Why Gettysburg Matters: The What Ifs

Actual “What Ifs” arose after the war ended and those questions elevated Gettysburg as a symbol regarding leadership, race relations, and ways of understanding broader issues of North/South relations that are still with us today.

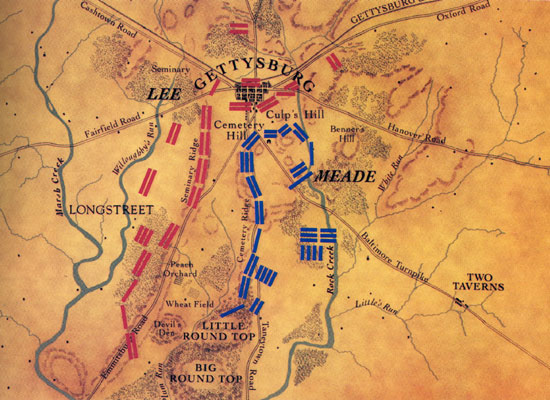

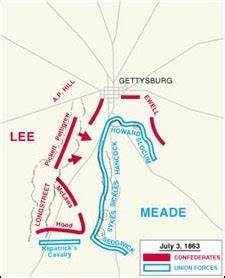

Jubal Early rose to the rank of Lt. General in the Confederate army and played a role in the Battle of Gettysburg. At Gettysburg, Early held the rank of Major General, a rank one step below Lt. General. Early commanded a division within a corps commanded by Lt. General Richard Ewell. On the first day of battle (July 1st), Early’s division drove Union troops through the town of Gettysburg forcing them to retreat up an incline and take up positions on what is known as East Cemetery Hill. It appears, since this would call for accurately understanding the circumstances of what was developing at that moment, that Early wanted to continue the assault up to East Cemetery Hill but that he was ordered to halt his assault by Ewell. This could have been a critical lost opportunity since if Confederate forces had captured East Cemetery Hill, it might have prevented Union forces, under the command of Major General George Meade, from strengthening their positions on the high ground around Gettysburg.

The issue of the Fog of War, in this situation interpreting command orders, arose. Lee gave Ewell orders to take East Cemetery Hill “if practicable.” Those two words could have been the difference regarding where Confederate forces would be positioned at the end of the first day at Gettysburg. 28

Ewell was promoted to the rank of Lt. General, taking over the Second Corps, after Lt. General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson died from wounds accidentally inflicted by his own troops at the Battle of Chancellorsville (Virginia, shot May 2, 1863, died May 10). After Jackson’s death, the size of the Second Corps was reduced to shift some of those troops to a newly created Third Corps headed by Lt. General A.P. Hill (who, like Ewell served as a Major General under Jackson). Would Jackson have interpreted Lee’s vague orders regarding assaulting East Cemetery Hill different than the way they were interpreted by Ewell? Would East Cemetery Hill, therefore, have been in Confederate hands at the end of the first day of fighting at Gettysburg? There is no way to draw a conclusion regarding either of these questions. Part of the problem with both questions is that they assume that Jackson could have done it all and this type of thinking completely ignores the defensive actions of Union forces defending East Cemetery Hill.

Gingrich and Forstchen seem to assume that if Jackson were alive and with Lee at Gettysburg, the fighting and the outcome of the battle might have been different. Toward the beginning of their book, Gingrich and Forstchen have Lee thinking to himself, “If Jackson were here, I would know without a moment’s doubt how to react. But all had changed now.” 29 Of course, the composition of the Confederate army might have been different if Jackson had lived. The Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia would probably not have been reorganized and would have been bigger and maybe there would have been no Third Corps, so the number of troops involved in an assault on East Cemetery Hill would have been different. In addition, with or without Jackson’s death, there might have been changes made to the organizational structure of the Army of Northern Virginia: In January 1863, President Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy wanted regiments transferred into brigades so that all brigades were composed of troops from the same state. 30 How this type of change impacted the effectiveness of Confederate troops in combat is debatable.

After the war, Early, among others, would be critical of Ewell, blaming him for much of the Confederate losses at Gettysburg, shifting blame away from Lee for having issued vague orders in the first place.

Ewell has been described as a cautious commander who was inclined to not take chances. One study regarding earlier engagements he was involved in described him as, “show[ing] a predilection for indecision.” 31 Interestingly, in the Gingrich and Forstchen book, the authors have Lee confront Ewell regarding his lack of advancement on the battlefield when he was ordered to do so:

Lee: You did not do as ordered, sir.

Ewell: Sir, I thought it prudent not to.

Lee: Prudent? …I did not ask for prudence; I ordered you to show leadership. …General Ewell you are relieved of command. 32

Gingrich and Forstchen may have found a way to make Ewell look like a poor commander: Fiction writers who managed to place a great deal of blame on Ewell, while historians argue over the merits of whether to blame Lee or Ewell at what could have been an important moment for Confederate forces.

Why all this matters regarding Early is that later in the war, Lee relieved him of his command. Much of this had to do with Early losing the confidence of political leaders and Lee seemed to be acting in a way to address their concerns. His letter to Early, essentially ending his military career, reads:

While my own confidence in your ability, zeal, and devotion to the cause is unimpaired, I have nevertheless felt that I could not oppose what seems to be the current of opinion, without injustice to your reputation and injury to the service. I therefore felt constrained to endeavor to find a commander who would be more likely to develop the strength and resources of the country and inspire the soldiers with confidence, and to accomplish this purpose I thought it proper to yield my own opinion, and defer to that of those to whom alone we can look for support. I am sure that you will understand and appreciate my motives, and that no one will be more ready than yourself to acquiesce in any measures which the interest of the country may seem to require, regardless of all personal considerations. 33

Early played a critical role in the interpretation of Gettysburg after the war ended—which is a reason to understand why this battle continues to receive so much attention. There are these moments where, it is believed, if an order had been followed differently, or if a military unit had advanced and held certain ground, or if a cavalry unit had arrived sooner to the battle, the outcome of Gettysburg would have been different. Early may have felt bitterness regarding the way his Confederate Army service ended and saw a need to continue the fight well after the war ended. That moment on the first day of Gettysburg, if he had been allowed to advance up to East Cemetery Hill, would it have secured him a military reputation which could have carried over after the war ended?

Early was not just critical of Ewell, he went after Longstreet in an odd way. On January 19, 1872, two years after Lee had died, seven years after the war ended, Early gave a speech at Washington and Lee University and stated that Longstreet had failed to follow Lee’s orders to launch an attack early on the morning of the second day (July 2nd). A year later, this assertion was repeated by William Pendleton, who served as a Brigadier General in the Confederate Army. Lee, in fact, wanted to remove Pendleton from command but he was a close friend of Jefferson Davis. Two former Confederate generals who had run-ins with Lee, both did their best to make Lee look good by shifting the blame for the outcome of Gettysburg to Longstreet. It seems these two former Confederate generals invented orders that never existed. 34 Shaara described Early as:

[A] man who works with an eye to the future, a slippery man, a careful soldier; he will build his reputation whatever the cost. …Longstreet despises him. Lee makes do with the material at hand. Lee calls him “my bad old man.” 35

Longstreet himself seemed puzzled when he heard about this allegation. In fact, he sought assurances from those who were in command positions during the battle that such orders to attack early on the morning of July 2nd, never existed. Lt. Colonel Walter Taylor was aide-to-camp to Lee during the war and sent a letter to Longstreet in 1875 that stated:

I can only say that I never before heard of the ‘ sunrise attack’ you were to have made, as charged by General Pendleton. If such an order was given you I never knew of it, or it has strangely escaped my memory. I think it more than probable that if General Lee had had your troops available the evening previous to the day of which you speak, he would have ordered an early attack, but this does not touch the point at issue. I regard it as a great mistake on the part of those who, perhaps because of political differences, now undertake to criticise and attack your war record. Such conduct is most ungenerous, and I am sure meets the disapprobation of all good Confederates with whom I have had the pleasure of associating in the daily walks of life. 36

The “political differences” that Taylor referred to were based upon Longstreet becoming a Republican during Reconstruction (1865-1877) and that he endorsed Ulysses S. Grant for President in 1868: Abraham Lincoln was the first Republican President so Republican was a dirty word in the South. 37

This issue of Longstreet and how to assess him matters to both novels discussed in this essay. Thomas Desjardin, a Civil War historian and former archivist at the Gettysburg National Park Service, pointed out about Gettysburg, “there are a multitude of meanings that Americans have attached to the story of Gettysburg:” 38 Gettysburg is not just history; it is also about contemporary attitudes and opinions that have developed about the Civil War. Gettysburg matters because it provides insight into how we see and understand America now.

Personalities, Forced Action, and Command

Lee has been described as “the marble man,” a nickname he received from his classmates at West Point. But it also conveys an image of a cold and distant statue. 39 One military historian referred to Lee at Gettysburg as possessing “limited imagination.” 40

In both The Killer Angels and Gettysburg: A Novel, Lee is presented as human with all the emotions that go with being human. In The Killer Angels, Shaara refers to Lee as “The King of Spades,” a reference to a term given by his soldiers after he took command of the Army of Northern Virginia in 1862 and built up the defenses protecting Richmond, Capital of the Confederacy. As a Union officer put it, “Opinions seem to differ as to Gen[eral] Lee as a tactician or an invader, but all agree that when it comes to defensive operations, ‘Old Bob’ understands his business.” 41

In The Killer Angels, Shaara presents Lee as a commander who seems either forced or possessed to go on the offensive. Shaara refers to Davis having written a letter to Lincoln calling for a truce. But the only way that letter would be received and perhaps acted upon, would have been if Lee could win at Gettysburg. In other words, broader forces were pushing Lee to act almost impulsively at Gettysburg. Shaara’s novel helps to convey that command decisions are not isolated to the circumstances of a moment in time but fit within broader developments.

Elsewhere, Shaara constantly shows Lee complaining that Major General Jeb Stuart and his cavalry, who are his eyes and ears as to Union troop movements is out of communication: Stuart and his cavalry will arrive on the second day (July 2nd) of the battle. Longstreet, however, has a spy who gives information, accurate it turns out, as to Union troop movements. Lee states, “Am I to move on the word of a spy?” 42 His low opinion of a spy is costly, preventing Lee from acting quickly to secure terrain positions that would be beneficial. Shaara has a conversation between Lee and Longstreet, which indicates Lee’s reluctance to act on information from a spy:

Lee: There should have been something from [Jeb] Stuart. There should have been. Stuart would not have left us blind.

Longstreet: He’s joyriding again. This time you ought to stomp him. Really stomp him.

Lee: Stuart would not leave us blind. 43

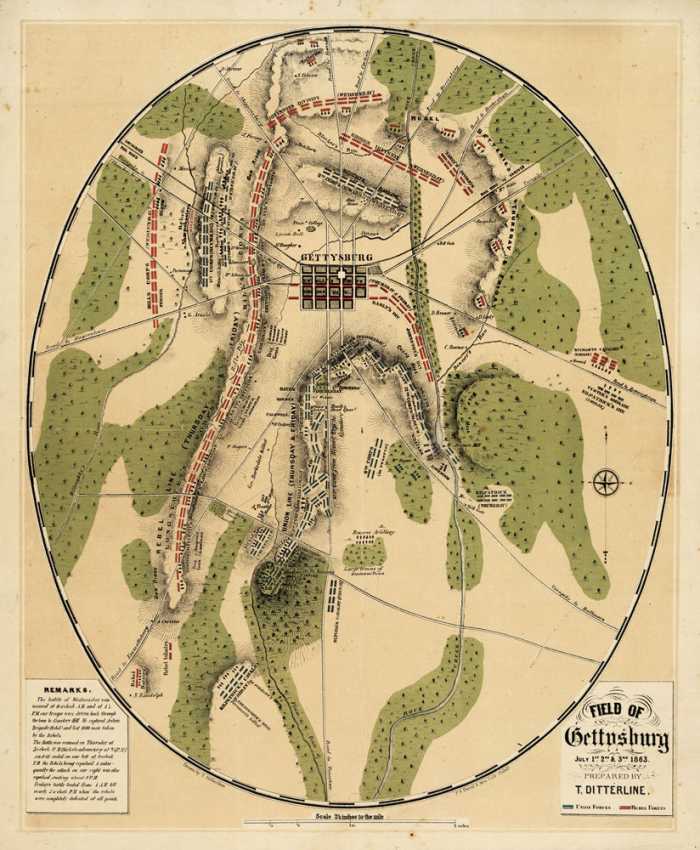

Union Brigadier General John Buford saw the advantage of terrain at Gettysburg and in Shaara’s novel he says to one in his command, “The whole damn Reb army’s going to be here in the morning. They’ll move right through town and occupy those damned hills.” 44 Buford was referring to the high ground position around East Cemetery Hill. East Cemetery Hill is part of this high ground, which begins with Culp’s Hill, then connects to East Cemetery Hill and turns to Cemetery Ridge, which leads to Little Round Top—essentially an upside down J if you look at it from above. So, Lee’s character judgment of a spy matters, and a novel can provide a sense of leaders and their personalities and how that matters to the course of a battle: The high ground was lost to the Confederates. Shaara emphasized the importance of East Cemetery Hill:

[Buford] was in possession of good ground at Gettysburg. …Buford could hold it. If not, Rebs would take it and there was no ground near that was any good. Buford did not know how long his two brigades could hold. 45

Shaara has Buford make some remarks to someone in his command about the importance of the position they were holding. Buford states, “I want to save the high ground, if we can. …[T]he point is to hold long enough for the infantry. If we hang onto these hills, we have a good chance to win the fight’s that coming.” 46 These repeated references to Buford speaking and Shaara describing what Buford thought, help to convey the importance of terrain advantage.

In Gettysburg: A Novel, Gingrich and Forstchen present Lee as reluctant, but then willing to listen to a plan to defeat Union forces presented by Longstreet. Some of Lee’s reluctance to listen to Longstreet comes from the way he is described by the authors, “Longstreet, the old warhorse. Solid, reliable, but everyone knew that he could be too methodical, slow, firm of opinion.” 47 Lee, on the other hand, is described in a way quite contrary to Longstreet, “the one weakness of Lee, an aggressiveness that bordered on pure recklessness if his blood was up and he smelled victory.” 48

Opinions by military analysts and historians do not always see Lee as having been a great general. One military historian commenting on Lee wrote, ” [His] tendency to move to direct confrontation, regardless of the prospects of the losses that would be sustained, guaranteed Lee’s failure as an offensive commander.” 49 British General J.F.C. Fuller, a prolific author on military affairs, wrote of Lee, “the more we inquire into the generalship of Lee, the more we discover that Lee, or rather the popular conception of him, is a myth.” 50 Personalities rise to the surface and matter greatly in tense situations, and planning for the unfolding of events that will lead to many deaths, certainly qualifies as a tense situation.

The lessons, or rather memories, from previous battles, no doubt weigh on any commander as they are preparing for their next battle, their next campaign. In Gettysburg: A Novel, Gingrich and Forstchen do a good job referring to how previous battles weigh in evaluation as Gettysburg unfolds.

Meade was new to command of the Army of the Potomac, having only assumed command on June 28, 1863, four days before the start of the battle, replacing Major General Joseph Hooker. In one exchange that Meade has with Brigadier General Henry Hunt, Chief of Artillery, Meade wants to understand Lee and knew that Hunt knew Lee from before the war. Hunt says:

Lee might take the reins himself rather than let his subordinates run things once battle is joined. I heard from prisoners that he fought the ending of Chancellorsville that way, right down to taking charge of individual brigades. He might do that again next time, and if so, be careful, sir. He’ll come in hard then. If blunted, look for a flank. Keep a sharp eye on the flank, sir. 51

Malvern Hill (Virginia) is referred to more than once in Gettysburg: A Novel. Malvern Hill was a battle that took place exactly one year before the first day of Gettysburg. Union artillery mattered and through a series of confusing orders and miscommunications, Confederate infantry repeatedly assaulted Union positions across open fields without supporting Confederate artillery fire, only to be repulsed back by artillery fire. Despite what appeared to be a Union victory, Major General George McClellan, withdrew his forces, ending the siege of Richmond: Lee was the victor. There is a famous quote regarding Lincoln commenting on McClelland, “If General McClellan isn’t going to use his army, I’d like to borrow it for a time.” 52 Gingrich and Forstchen write:

Malvern Hill was a sore spot with Lee, a battle he wished he had never fought, a disaster of disorganized brigades charging up an open slope into the muzzles of over a hundred Union guns. 53

Lee reflected back on Malvern Hill states, “It will never happen. …Always consider the position from the view of your opponent. Look at this place, [w]ould you attack if they were up there?” 54

Fiction allows the writer(s) to put themselves in the minds of commanders and allows readers to develop a grasp of thinking that seems logical:. The mistakes and successes of past battles are remembered and can weigh on command decisions which can be conveyed well through conversations created in novels.

Pivotal Figures: Nobel and Daring

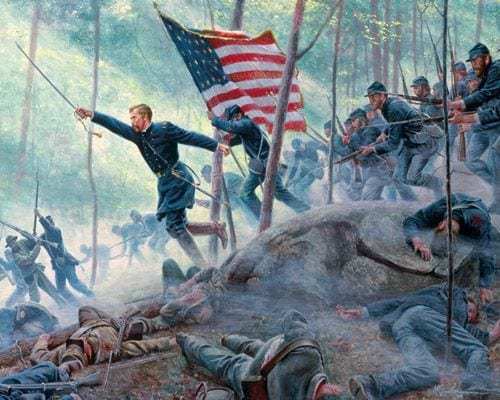

The first day of fighting was concentrated around Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill. The second day of fighting shifted to the other side of the battlefield near Little Round Top. The terrain here, as during the first day, favored Union forces. Basically, the battlefield encompassed two ridge lines with Confederate forces up on Seminary Ridge and about a mile away on more or less a parallel ridge line was Cemetery Ridge, which was higher than Seminary Ridge. For Confederate forces to attack Union positions, they needed to descend into the valley between the two ridge lines and then proceed up steep inclines. In some cases, boulders blocked their advances in the vicinity around Little Round Top. 55

There is some confusion why when some Confederate forces made it to Big Round Top, located near Little Round Top, they did not hold that position and strengthen it. The slope of the hill and boulders on the hill, may have made it difficult to get artillery up to the top or place any artillery in a way that could allow for firing on Union lines: 56 Controlling the high position, however, might have helped infantry fire aimed at Union troops on lower terrain.

Shaara developed his hero around fighting that took place on Little Round Top. Colonel William Oates commanded the 15th Alabama Regiment that confronted the 20th Maine regiment, under the command of Colonel Joshua Chamberlain at Little Round Top. Oates was the only Confederate unit commander who lived to tell the tale of Little Round Top from the Confederate perspective. In his rendering of the fighting, he placed the size of his force as twice that of Chamberlain’s. This mistake, which was way off the actual size of his force, helped to increase the legend of Chamberlain, since it created the appearance of Chamberlain fighting against forces superior in size to the 20th Maine. 57

On the march to Gettysburg, Chamberlain has one of his soldiers look at him and he expresses his attitude toward the war, which reflected a sentiment shared by many Union soldiers:

I’m tired, Colonel. You know what I mean? I’m tired. I’ve had all of this army and all of these officers. …We ain’t gonna win this war. We can’t win no how because these lame-brained bastards from West Point, these god-damned gentlemen, these officers. …I just as soon go home and let them damn Jonnies go home and hell with it. 58

With this sentiment, Shaara manages to convey the importance of the Union side winning the Battle of Gettysburg. As a result, Gettysburg is a critical moment in the Civil War—a turning point: Shaara sets the stage for Chamberlain to step forward and take his place in history. Shaara described how he saw Chamberlain:

He had a complicated brain and there were things going on back there from time to time that he only dimly understood, so he relied on his instincts, but he was learning all the time. The faith itself was simple: he believed in the dignity of man. 59

Shaara’s elevation of Chamberlain to penultimate hero, was built upon an 1883 book published by Theodore Gerrish, who was a member of the 20th Maine regiment. The book addressed the actions of the regiment at Little Round Top, although it was later revealed that, at the time of the fighting, Gerrish was in Philadelphia, nowhere near Little Round Top. 60 Gerrish wrote:

Stand firm ye boys from Maine, for not once in a century are men permitted to bear such responsibility for freedom and justice, for God and humanity as are now placed upon you. 61

Once a fiction writer takes what a Civil War participant has written, people and places take on an added importance.

Shaara did a better job describing the events that took place on the second day of fighting at Little Round Top. Shaara’s account is based on what happened, although precise recollections would vary, which must be understood, since life and death were hanging in the balance. One account estimated some 40,000 bullets were shot in the vicinity of Little Round Top on that day.

Confederate infantry units stormed up Little Round Top, only to be repulsed several times by Union units, including the 20th Maine regiment in the defense of the hill. One study of the events involving Little Round Top stated, “There is significant confusion surrounding the events leading up to the defense of Little Round Top.” This study then concluded, “a close examination of the events prior to the actual defense of Little Round Top…show that the individual initiatives of a number of officers of the Army of the Potomac…contributed significantly to the successful garrisoning of the hill.” 62

Colonel Woodward Rice, in command of the 44th New York Infantry regiment, coordinated his regiment’s actions with those of the 20th Maine. In a report written three weeks after the battle ended, Rice praised Chamberlain, and, in fact, stated that Chamberlain’s regiment was out of ammunition and wrote, “The ammunition came promptly, was distributed at once, and the fight went on.” 63 Rice’s bland description contrasts with Shaara’s conversation between Rice and Chamberlain, after the fighting had stopped, after Chamberlain led his unit in a final charge to repel Confederate forces. Although well after the war ended as one historian who wrote about the 20th Maine and their actions at Gettysburg put it, “[Chamberlain]…stated that he had not given the order which initiated the charge but asserted that he was with the colors during their lunge down the hill.” 64 Nevertheless, Shaara created a good conversation:

Rice: Colonel Chamberlain, may I shake your hand?

Chamberlain: Sir.

Rice: I watched that from above. Colonel, that was the damnedest thing I ever saw.

(A private whispered to Chamberlain): Colonel, sir, I’m guardin’ these here Rebs with an empty rifle.Chamberlain: Not so loud. Colonel Rice, we sure could use some ammunition.

Rice: You’re not regular Army? You’re a professor. Where’d you get the idea to charge?

Chamberlain: We were out of ammunition.

Rice: So. You fixed bayonets.

Chamberlain: It seemed logical enough. There didn’t seem to be any alternative. 65

Chamberlain and the 20th Maine played a role, even a significant one, in the defense of Little Round Top. But, to place all praise for the outcome of the defense of Little Round Top on Chamberlain, even in ways elevating him above the regiment he commanded, as Shaara did, is fiction. Sixteen years after Shaara’s novel was published, in 1990, Ken Burns produced his widely popular series, The Civil War: Once again Chamberlain was raised to the level of penultimate hero. Burns stated:

[F]or all intents and purposes, it was the life of Chamberlain which convinced me to embark on the most difficult and satisfying experience of my life, to tell the whole story of the Civil War. 66

Fiction helps to highlight that individual events, such as the actions of one colonel, can matter to the course of a battle. Whether this one event merits the status of determining the outcome of the Battle of Gettysburg, or even more than that, the outcome of the Civil War, can only be described as literary license.

Pivotal Figures: Imaginative

Gettysburg: A Novel to some extent, does for Longstreet whatThe Killer Angels did for Chamberlain. Longstreet is perhaps the major Confederate figure who needed a revision in understanding his role and importance in the Civil War. As pointed out earlier, Longstreet became a Republican after the war which led to wide condemnation by Southerners for decades. Longstreet was never criticized by Lee in any wartime reports, but none of that mattered after the war ended and after Lee died in 1870. As one study stated, “[The] scapegoating of Longstreet offered southerners a temptingly simple explanation for defeat, one that did not call into question southern manhood or the loss of God’s grace. 67

There is a brief conversation in The Killer Angels that provides some understanding that what Longstreet proposed, and was acted on by Lee, in Gettysburg: A Novel: Longstreet’s proposal had a basis in practicality. Shaara has Lee state in a conversation on the morning of July 2nd with his commanders:

General Ewell has changed his mind about attacking to the left [to assault East Cemetery Hill again]. He insists the enemy is too firmly entrenched and has been heavily reinforced in the night. I’ve been over these personally. I tend to agree with him. There are elements of at least three Union corps occupying those hills.

…[An] attack on the right [toward Little Round Top] would draw off Union forces that then [Cemetery Hill could be taken. [With]drawing from Gettysburg, giving it back to the enemy, would be bad for morale, is unnecessary, and might be dangerous. 68

Lt. General John Bell Hood makes a proposal, “General, I’d like to send one brigade around [the] rocky heights. I think I can get into their [supply] wagon trains back there.” 69

There are aspects of what Hood proposed that are expanded on in Gettysburg: A Novel—and Longstreet is the architect of the plan.

Gettysburg: A Novel, for the most, follows closely with the events of the first day of fighting. Lee makes a statement to Longstreet indicating Longstreet’s importance to Lee:

General Longstreet, you are now my right arm. I ask you to understand that. I could always count on you in the defense; you demonstrated that at Sharpsburg and Fredericksburg. I need more from you now, General, much more. I need your voice of caution, but I need you to see the opportunity for attack, for audacity. 70

While Shaara displays Lee as listening to Longstreet, but then essentially dismissing his cautionary ideas, Gingrich and Forstchen set the stage that Lee is more willing to seriously consider what Longstreet has to say. The contrast between the two novels puts the onus clearly on Lee for the disaster that befell the Confederates at Gettysburg. In the case of the Gingrich and Forstchen book, clearly identifying Lee as responsible for the Confederate loss at Gettysburg, is not anywhere addressed in their novel. But, based on what Gingrich and Forstchen have Longstreet propose and Lee expand upon as a way of drawing Union forces away from Gettysburg toward more favorable terrain, the implication is that Lee is made to look bad regarding the real outcome after three days of fighting.

On the afternoon of the first day of fighting, Lee accepts that a renewed assault around East Cemetery Hill could be disastrous. In Gettysburg: A Novel, Lee addresses Longstreet:

[W]e’ve done well today, very well. We don’t want to get tangled up in that town. If we try for that next hill now, we might be sticking our necks out. 71

Despite Lee’s concern he ordered Ewell to press on with an assault on East Cemetery Hill. Within several hours, the assault was repelled by Union forces, which were beginning to be reinforced by Union infantry. It is as the fighting on the first day ends, with Confederate forces on ground below the high hills around Gettysburg that Longstreet proposes his plan:

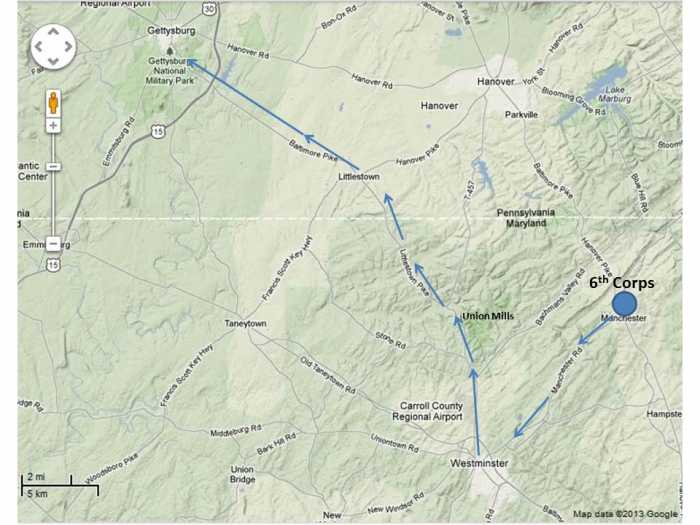

Sir, go south of those hills. …Cut the Taneytown Road without a fight. Move toward the Baltimore Road. above this place. We do that, sir, and it will dislodge them from here without a fight, and then we pick the ground [where to fight]. 72

With Confederate forces gathered around Seminary Ridge, the plan is to swing widely around their right side, avoiding a frontal assault at Cemetery Ridge. This flanking action ran counter to tactics taught at West Point–which influenced military leaders on both sides in the Civil War. As one scholar put it:

Civil War tactical theory emphasized operating offensively. Military theory, which was taught at West Point and reiterated in the tactical manuals of the period, strongly recommended the tactical offensive; the concept that field fortifications should be vigorously assaulted; a high regard for use of the bayonet both offensively and defensively; and dependence on the traditional, close-order formations. 73

As Longstreet is proposing his flanking action, Lee interrupts him to build upon Longstreet’s plan. Lee states that Meade will concentrate his forces along Cemetery Ridge and merely flanking behind them will still have Confederate forces continuing to face a strengthened Union force on terrain favorable to Meade. Lee states:

If they are here tomorrow, what is behind them? Not just behind the hills, sir, that you suggest we flank, but farther back, ten miles, twenty miles? …Nothing, except their supplies, which are most likely based at Westminster. 74

Westminster is located approximately 40 miles southeast from Gettysburg and so Lee, expanding on Longstreet’s plan, wants the battle shifted well away from Gettysburg. Stuart’s cavalry, as well as several other infantry units will stay at Gettysburg to convince Meade that Lee is planning a renewed assault on his positions, while Longstreet leads the bulk of Lee’s army on an extended flanking operations, that leads to battle around Union Mills, Maryland (located about halfway between Gettysburg and Westminster, Maryland). In the process, Longstreet’s forces manage to capture Union supply trains and fight on terrain more to their advantage.

The What Ifs of Gettysburg help to highlight the importance of terrain. In addition, the conversations that the two authors develop between Lee and Longstreet show what a healthy and productive exchange could mean between a commander and his staff. The What Ifs go beyond just maneuvering and positioning forces, to what leadership means: The commander at the top needs to be open to proposals that may run counter to their inclination. Lee, ever the commander to press for offensive assaults, is convinced to change to military operations involving a great deal of maneuvering.

Arming Slaves or Arming Men Freed?

If Confederates had won at Gettysburg, what would have happened next? Slavery, the overriding issue that is touched upon in The Killer Angels, but never addressed in Gettysburg: A Novel, would still need be to be addressed. In fact, in The Killer Angels, Chamberlain remembered an interracial couple living in his vicinity in Maine. Shaara wrote, as though Chamberlain was remembering:

You saw few black men in New England. Chamberlain knew one to speak to: a silent roundheaded man with a white wife, a farmer, living far out of town, without friends. 75

Chamberlain further remembered a conversation before the war with a Southern minister, he thought, “White complacent face, sense of bland superiority: my dear man, you have to live among them, you simple don’t understand.” 76

As the war was going badly for the South, a proposal was made to arm slaves to fight for the Confederacy. Lee seemed to lean toward giving those who fought their freedom after the war ended. But Lee indicated a superior position for whites and wrote in January 1865:

Long habits of obedience and subordination, coupled with the moral influence which in our community the white man possesses over the black, furnish and excellent foundation for that discipline which is the guaranty of military efficiency. 77

Before the Civil War began in 1861, Lee wrote a letter to the New York Times in which he seemed to express some regret for slavery, “In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil in any Country.” But then he added that, “[slavery was] “a greater evil to the white man than to the black race.” 78 Lee might appear to have been sympathetic toward addressing slavery as an institution but then again, his sentiments might have meant nothing since his attitudes and actions did not indicate any real remorse or concerns. In The Killer Angels, Shaara says of Lee, “He does not own slaves nor does he believe in slavery, but he does not believe that the Negro, ‘in the present stage of his development,’ can be considered the equal of the white man.” 79 Shaara’s description of Lee regarding slavery may be kind.

The proposal that emerged out of the Confederate government was that freedom would be determined by the slave masters, even if slaves fought—which was no guarantee of anything. This measure passed the Confederate Congress in March 1865, two months before the war ended.

It is difficult to completely understand how armed slaves fighting with white Southerners would have been accepted by white soldiers. One study of Confederate soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia pointed out that slave owners were more likely to make up the composition of Confederate troops than the general population of the South in the first year of the war. As this study stated, “volunteers in 1861 were 42 percent more likely to own slaves themselves or to live with family members who owned slaves than the general population.” 80

Beginning in 1862, Confederate Conscription acts were passed, which originally allowed those drafted to hire substitutes: That was abolished within a year. So, as the war progressed, the percentage of Confederate soldiers who owned slaves might have changed. But attitudes toward arming slaves to fight was reflected in the diary of one Confederate soldier when he found out the North was arming former slaves. As he wrote, “the Yankees are drilling the negroes to fight us…[we now face] the bloody year of the war.” 81

The Davis Administration made a decision that black soldiers captured were not to be treated like white soldiers: It was understood black soldiers would be killed. At the Battle of the Crater in Petersburg, Virginia, Confederate troops came up against black Union soldiers. A New York Times account from April 1864, mirrored the actions of Confederate troops at Fort Pillow when black troops tried to surrender. The Times stated:

On the morning after the battle the rebels went over the field, and shot the negroes who had not died from their wounds . . . . Many of those who had escaped from the works and hospital, who desired to be treated as prisoners of war, as the rebels said, were ordered to fall into line, and when they had formed, were inhumanly shot down. Of 350 colored troops not more than 56 escaped the massacre, and not one officer that commanded them survives. 82

Robert E Lee commanded Confederate forces at Petersburg and there is no indication that he took action against his troops for their killing of Union soldiers after they surrendered. In the case of Forrest at Fort Pillow, again, Lee’s silence is noticeable. 83

After Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862, it sort of freed slaves in the Confederate states. The “sort of” was based on the premise that if they escaped and made their way to a Northern state, they were free. The reaction to news of the proclamation by Confederate soldiers was expressed in a letter one soldier wrote to his wife based on false rumors that, “freed slaves immediately began hanging innocent whites, killing livestock, ransacking property, and otherwise destroying every vestige of society.” 84

With Confederate troops set in their ways regarding how they approached Union black troops, arming slaves to fight for the Confederacy was summed up by one historian, “The black enlistment question precipitated a social crisis that finally broke the Confederate rank and file.” 85

Where slaves performed services for the Confederacy during the war, was in the role of camp servants. As one writer put it:

Anywhere between 6,000 and 10,000 enslaved people supported in various capacities Lee’s army in the summer of 1863. Many of them labored as cooks, butchers, blacksmiths and hospital attendants, and thousands of enslaved men accompanied Confederate officers as their camp slaves, or body servants. These men performed a wide range of roles for their owners, including cooking, cleaning, foraging and sending messages to families back home. Slave owners remained convinced that these men would remain fiercely loyal even in the face of opportunities to escape, but this conviction would be tested throughout the Gettysburg campaign. 86

Slave labor was part of the Confederate war machine.

Fiction and History Complement Each Other

Despite the issue of slavery, these two novels provide a means to study a battle in a way that historical accounts, for the most part cannot: Fiction can enrich the study of history. Furthermore, that the North would win the war, and therefore slavery would end, was not a foregone conclusion. Two novels help to show the precariousness of the situation: A change of mind by Lee or a change of fortunes at one point in the battle and the outcome could have been different. Fiction can add to the suspense, drama, and life and death that war entails. Fiction further helps to present the battle as it was unfolding, as well as could have unfolded. 87

Historical accuracy does not need to come from the novelist, the historian can do that. The novelist provides a different means to fill in and enhance perspectives that historians may not be able to accomplish. To wonder what type of conversations Lee had with his generals or what a Union colonel was thinking as he decided to charge down a hill at approaching enemy forces, can be outside the reach of an historian, but not a novelist. As an added dimension to using fiction to enrich the study of history, the use of two novels which can be compared and contrasted regarding how they approach, in this case, a specific battle, provides perspective which simply relying on one novel cannot.

Works Cited

- John Keegan, The Face of Battle: A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo, and the Somme, New York, Penguin Books, 1976 ↩

- Thomas Desjardin, These Honored Dead: How the Story of Gettysburg Shaped American Memory, Cambridge, MA, Da Capo Press, 2003, pp. xv-xvi ↩

- Michael Shaara, The Killer Angels: A Novel, New York, Ballantine Books, 1974 ↩

- https://www.eenews.net/stories/1063516551 ↩

- Newt Gingrich and William Forstchen, and Albert Hanser, contributing editor, Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War, New York, St. Martin’s Paperbacks, 2003 ↩

- Grant Comes East, New York, Thomas Dunne Publisher, 2004, and, Never Call Retreat: Lee and Grant: The Final Victory, New York, Thomas Dunne Publisher, 2005, are the other two novels. ↩

- https://www.archives.com/experts/bilby-joe/civil-war-unit-structures-military-records.html#:~:text=Civil%20War%20Unit%20Structures%3A%20A%20Basic%20Breakdown%201,…%204%20Brigades%2C%20Divisions%20And%20Army%20Corps.%20. This is a useful short description of the military structure. ↩

- In the 1980s, I won a fellowship through TRADOC, the US Army’s Training and Doctrine Command, to spend a month at West Point studying military history, which led to an offer to write about nuclear strategy. As part of that program we went on staff rides at Antietam and Gettysburg with Jay Luvaas. Staff rides are discussed in William Glenn Robertson, The Staff Ride, Wash., DC, Center of Military History, 1987 ↩

- James McPherson, The War That Forged A Nation: Why The Civil War Still Matters, New York, Oxford University Press, 2015 ↩

- https://paw.princeton.edu/article/princeton-confederacys-service ↩

- Quoted in https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/23/books/review/lost-cause-meacham.html?searchResultPosition=1 ↩

- In the early 1980s, a good friend was serving as the chairman of a county commission in Florida. The commission was required to determine a specific number of official holidays the county would recognize: He proposed eliminating Confederate Memorial Day and substituting Martin Luther King, Jr. Day–for his proposal he received death threats. ↩

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2018/10/28/civil-war-massacre-that-left-nearly-black-soldiers-murdered/ ↩

- https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/168687 ↩

- https://deadconfederates.com/2012/08/02/what-they-saw-at-fort-pillow/ ↩

- https://www.newschannel5.com/news/newschannel-5-investigates/fact-check-was-nathan-bedford-forrest-a-kkk-leader-probably ↩

- https://www.huffpost.com/entry/general-nathan-bedford-fo_b_7734444 ↩

- https://www.newschannel5.com/news/newschannel-5-investigates/fact-check-was-nathan-bedford-forrest-a-civil-rights-leader-not-exactly ↩

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/nathan-bedford-forrest-day-tennessee-governor-signs-proclamation-2019-07-12/. ↩

- McPherson ,op.cit., p. 2. One source on Antietam is : http://necrometrics.com/battle19.htm#Antietam ↩

- This is one site this addresses casualties: https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/civil-war-casualties ↩

- https://www.civilwarhome.com/casualties.htm ↩

- https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/civil-war-casualties ↩

- Aaron Sheehan-Dean in, The Calculus of Violence: How American Fought the Civil War, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 2018, refers to 750,000 dead–which, also, questions the traditionally used 620,000 dead count, https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3411&context=cwbr ↩

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/death-numbers/ , and, https://www.civilwaracademy.com/civil-war-diseases ↩

- https://discovere.binghamton.edu/news/civilwar-3826.html ↩

- https://www.clarabartonmuseum.org/mso/ ↩

- https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2019/02/08/ewell-at-cemetery-hill/ ↩

- Gingrich and Forstchen, op.cit., p. 4 ↩

- https://www.historynet.com/jefferson-davis-commander-chief.htm ↩

- Peter Svenson, Battlefield: Farming a Civil War Battleground, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992, p. 124 ↩

- Gingrich and Forstchen, op.cit., p. 461 ↩

- https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/104/1175 ↩

- This issue of early morning orders is discussed here: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/07/longstreet-controversy-gettysburg-108538 ↩

- Ibid., p. xiii ↩

- https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/longstreet-gettysburg-second-day#.XypBdlH_iPE.email ↩

- The term “closet Republican” was used up until the 1980s, even in Florida. This term referred to Southern white voters who voted Republican, usually in Presidential elections, but did not express any open support for the Republican Party. After President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Southern white voters started moving toward the Republican Party in more open ways. The term “Southern Strategy” was popularized with Richard Nixon’s appeal to white Southern voters in the 1968 Presidential election. If white Southerners were so reluctant to even openly support the Republican Party as the 20th Century enfolded, imagine what Longstreet went through after the Civil War ended and it was still so vivid in the minds of white Southerners. ↩

- Desjardin, These Honored Dead, op.cit., p. xxii. ↩

- Thomas Connally, Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1977 ↩

- John Keegan, The Mask of Command, New York, Penguin Books, 1988. ↩

- https://emergingcivilwar.com/2015/02/03/no-bluffing-the-king-of-spades/ ↩

- Shaara, op.cit., p.15 ↩

- Ibid., p. 16 ↩

- Ibid., p. 42 ↩

- Ibid., p. 49 ↩

- Ibid., p. 51 ↩

- Gingrich and Forstchen, op.cit., p. 11 ↩

- Ibid., p. 27 ↩

- https://www.historyonthenet.com/effective-robert-e-lee-tactics-during-civil-war ↩

- https://www.historyonthenet.com/comparing-grant-and-lee-a-study-in-contrasts ↩

- Gingrich and Forstchen, op.cit., p. 35 ↩

- http://www.angelfire.com/my/abrahamlincoln/Quotes.html ↩

- Gingrich and Forstchen, op.cit., p. 48 ↩

- Ibid., p. 48 ↩

- Harold Winters, Gerald Galloway, Jr., William Reynolds, and David Rhyne, Battling the Elements: Weather and Terrain in the Conduct of War, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998, pp. 128-129 ↩

- https://www.historynet.com/big-round-top ↩

- Desjardin, These Honored Dead, op.cit., pp. 131-134 ↩

- Shaara, op.cit., p. 26 ↩

- Ibid., p. 29 ↩

- Thomas Desjardin, Stand Firm Ye Boys From Maine: The 20th Maine and the Gettysburg Campaign, New York, Oxford University Press, 1995, pp. 127-128. It is interesting that the author of this book, titled his book from words used in Gerrish’s book. ↩

- Ibid., Gerrish quote found here, p. 128. ↩

- http://www.gdg.org/Research/People/Chamberlain/savior1.html ↩

- https://ironbrigader.com/2014/06/22/colonel-james-c-rices-report-brigades-action-top-battle-gettysburg/ ↩

- Desjardin, Stand Firm Ye Boys, op.cit., p. 139. ↩

- Shaara, op.cit., p. 248 ↩

- Desjardin, These Honored Dead, op.cit., p. 147 ↩

- https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Longstreet_James_1821-1904#start_entry ↩

- Shaara, op.cit., pp. 193-194 ↩

- Ibid., p. 197 ↩

- Gingrich and Forstchen, op.cit., p. 50 ↩

- Ibid., p. 75 ↩

- Ibid., p. 139 ↩

- http://npshistory.com/series/symposia/gettysburg_seminars/6/essay1.htm ↩

- Gingrich and Forstchen, op.cit., p. 140 ↩

- Shaara, op.cit., p. 178 ↩

- Ibid., p. 179 ↩

- Alan Nolan, Lee Considered: General Robert E. Lee and Civil War History, Chapel Hill, NC, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991, p. 176 ↩

- https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/18/us/robert-e-lee-slaves.html ↩

- Shaara, op.cit., p. x ↩

- https://acwm.org/blog/myths-and-misunderstandings-slaveholding-and-confederate-soldier/. ↩

- Chandra Manning, What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 2007, p. 108 ↩

- https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/168687 ↩

- https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/06/the-myth-of-the-kindly-general-lee/529038/ ↩

- Manning, op.cit., pp. 106-107 ↩

- Ibid., p. 205 ↩

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/diaries-left-behind-confederate-soldiers-reveals-role-enslaved-labor-gettysburg-180972538/ ↩

- A short (approximately 17-minute video) from the American Battlefield Trust can be found here which shows the movement of Union and Confederate forces over the three days of Gettysburg. If you watch this video, pay attention to use of the term “interior lines” which refers to how Meade could reinforce units in the midst of fighting, which gave him an advantage over Lee and his placement of forces: https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/gettysburg-animated-map ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Respect to both sides for their participation and sacrifice. My own grandfather (of unknown generation) had dawned a union uniform.

Interesting. It’s enjoyable to check about family background. I hope you enjoyed my essay.

Michael Shaara brilliantly mixes historical facts with fictional elements! Love that book!

A good novel. I always wanted to write an essay addressing Shaara’s novel. I took a staff ride with an historian from the Army War College and we visited the sites at Gettysburg that are in Shaara’s novel.

One of the pivotal battles in history. The world would have been a very different place had Lee won. Exactly how different we will never know.

I have not read the other two novels in the trilogy by Gingrich and Forstchen. I wonder if after-the-war implications are addressed there.

Good article. Could I add one thing here?

Might be a good time to suggest reading some Walt Whitman. Two poems I think of as companion poems are Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night, and Come Up From the Fields, Father. In the context of remembering the battle of Gettysburg and the fearful slaughter, it is worth a quiet reading of both.

Thanks for enjoying my essay. I am planning several more articles similar to this–other Civil War battles.

Quick question: is it my imagination, or is there a choral piece by Britten that quotes a couple of Whitman Civil War poems?

Here’s a site on Walt Whitman’s Civil War poems: http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/ows/seminars/civilwarrecon/whitman/

The civil war was a fascinating lesson in how tactics evolve more slowly than the technology we use to kill each other… 60 years later it would be repeated on a much grander scale in WWI.

I have thought of an essay addressing tactics and what is learned and not learned and why. Thanks for reading my essay.

Indeed.

Why anyone believed that WW1 would be over by Christmas 1914 is a mystery to me.

After all the Civil War was between a heavily and a lightly industrialised state and that lasted for four years.

To an extent the idea that everyone believed that the war would be over quickly is something of an urban myth.

I suspect that by going to war in the first place, the belief is that your side (whichever that is) is far superior to the other side so victory will come quickly. Righteousness, I believe, has a great deal to do with going to war. While that is understandable, it may adversely affect how a nation actually plans for war–its strategy and therefore tactics. As a result poor strategy and tactics leading to poor implementation of both, will have an impact on the war you thought that would end quickly, leading to a war being drawn out.

You are correct about this one of many WW1 myths – few (on the Allied side) believed it would be over by Christmas although many hoped it would be. On the German side is another matter – they would not have unleashed it unless they believed they would win and win quickly.

Would have fancied the Germans on paper for WWI, but the two front war cost them as it prevented a knock-out blow, they advanced quickly westward at the beginning of the war causing panic in Paris, but troops defending their homeland eventually tend to fight harder while the early BEF force were crack shots, photos of mass ranks of German soldiers advancing over open ground hinted at their hubris. On the Eastern front they eventually hammered away at the Russians, who knocked themselves out of the war with the Russian Revolution, the quick transfer of troops by the Germans from one theatre of war to another while impressive was too late despite the initial successes of the 1918 campaign which eventually just ran out of steam, had Germany concentrated a knock-out blow first in the West followed by battle with the Russians it may well have turned out differently. I suspect ‘being over by Christmas’ was for domestic consumption and to ensure rapid levels of volunteers, once the true character of the war emerged as a bloody slugfest, the British and others were forced to introduce conscription to make up for the rapid rate of losses with the Somme being particularly noteworthy for epic military disaster.

Originally, it seemed the Germans planned to have a quick victory on the Western front then shift gears to fight the Russians. Planning a two-front war had to be difficult and it was, no doubt inevitable, that something had to go wrong to throw any thinking of easily shifting from one front to the other out the window. Tuchman, The Guns of August, is a good book to learn about the First World War.

Schlieffen Plan. I believe it was modified so not carried out the way it was originally laid out. I know German historians who feel that the modifications that were made to the plan contributed to the reason the First World War developed into trench warfare.

The Civil War seems such a long time ago, but interestingly there are still a handful of people alive today whose fathers were Civil War vets, the offspring of men who were very young soldiers during the Civil War but who as old men married young women and fathered children around the WW1 era. The last widow of a Civil War vet died in 2008, again a young woman who married an old vet and lived herself to an old age.

It is interesting how aspects of the Civil War still matter today. One of the issues I hopefully addressed in my essay.

There’s a novel called “Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All”, that points that out. The woman married a drummer boy, later in life, who was pretty young to be in a battle.

I keep wanting to read that novel, thanks for reminding me of it.

Just as there were still a handful of people alive even in the the year I was born who could remember being slaves when they were children. In that sense it wasn’t long ago at all.

Maudie Hopkins. She died in 2008. She is listed as the last wife of a Civil War soldier to die. Her husband served in a Confederate army.

For a good study on war, there is a docu on The Art of War by Sun Tzu, with modern instances to show what worked and what failed. Gettysburg is one of them.

Thanks for enjoying my essay. I had thought of an essay on The Art of War–always fascinating how often it is referred to in movies.

Lee screwed up, and his staff officer wouldn’t even hand on his order for the last assault, that sank them.

It is normal to read of historians now criticizing Lee for issuing vague orders.

The South really lost the war the following day when VIcksburg fell. Even if Lee had won at Gettysburg, capturing Washington was not a done deal. Few seem to remember that the best Union generals were in the West where with the notable exception of Chickamauga, the Union won nearly every major battle. The fall of Vicksburg coupled with the eventual breakthrough at Chattanooga were strategically more important.

In my essay I felt it was necessary to refer to Vicksburg so Gettysburg is not seen in isolation. One reason why I refer to a military historian (John Keegan) questioning whether a specific battle can be seen as a turning point in a war–rather several engagements need to be tied together.

I think the South could have held out a long time had they retaken Chattanooga after Chickamauga, or even had they been able to hold the Missionary Ridge Line.

As desperate as things were for Lee in the Spring of 1865, he could have held the Petersburg lines for a long time with more troops and he would have had them but for the Union successes in Georgia, Sherman’s March- and Thomas’s smashing destruction of Hood before Nashville.

As Catton said- only twice in the war did a Soutern Army flee the field and each time George Thomas struck the blow.

Perhaps but Lees problem at Petersburg was lack of supplies and a high desertion rate leaving him with too few troops to guard the lines. If Johnston had joined up with Lee, Sherman would have joined up with Grant and I suspect the outcome would be the same. The Union just had too many well fed, well equiped soldiers and finally the Army of the Potomac had a capable leader. Grant has been underestimated as a commander. His manuvers from the Wilderness to Petersburg were masterful. Apart from the folly at Cold tHarbor that is. Lee’s mistake was to try to guard Richmond getting pinned down in siege warfare. He was best in open field battles.

Thomas’s victory at Nashville was a think of beauty but he was aided by facing one of the dumbest commanders in the Confederate Army, John Bell Hood. Why Fort Hood is named after that moron is beyond me – must be a Texas thing. He distinguished himself at Antietam but wrecked the South at Franklin and Nashville.

There are numerous writings on the way the South could have conducted the war from the beginning or even later as the war seemed hopeless that could have been done to extend the war. The issue is always what would that have led to–more actions similar to Sherman’s March to the Sea, so even more destruction of the South.

An interesting comment. I need to look up George Thomas. Thanks for reading my essay.

The soldiers of the US civil war really had the best facial hair of any war in history.

Interesting comment. I wonder how that can be studied. I hope you enjoyed my essay.

I would dispute that on behalf of the Grande Armée. Vive les moustaches!

Facial hair in war as an essay. Sounds like a good idea.

The fashion of the American Civil War was strongly based on the fashion of armies in the Crimean War- both in terms of items of uniform and indeed facial hair. In the Crimea, the facial hair was prompted by a question of water supply for shaving and, much like the early and mid stages of the occupation of Afghanistan in the last decade, facial hair was adopted for ‘allyness’.

Fascial hair as an essay sounds like there is something there.

THE KILLER ANGELS is, in my opinion, the best fictional piece of work regarding what happened at Gettysburg. Thank you for covering it.

I always wanted to do an essay addressing Shaara’s novel. I hope you enjoyed my essay.

I don’t know why I am craving rereading this. I just know that I am … and I obey!

Ah, the marriage of literature and history–one of my favorite couplings. Well done!

I wanted for some time to do an essay addressing literature and a specific battle. As I was working on this essay, I started realizing the enormous number of novels on different Civil War battles. I have plans over probably the next year and a half to write 2-4 more essays addressing different Civil War battles and literature. Thanks for enjoying my essay.

I agree with this, too! I have spent the last three years of my life studying both literature and history at uni, so I enjoy the pairing. (Though, U.S. history specifically is not really an interest of mine, I’m more interested in events that have occurred closer to home.)

As someone who does enjoy both I think I personally disagree with the statement in your conclusion, “Historical accuracy does not need to come from the novelist, the historian can do that.” But that’s an idea that has been debated at length. Regardless, I really enjoyed reading this and the arguments you present!

Thanks for commenting. I guess I could have said, “A novelist has the luxury to not necessarily be accurate, as is the case with an historian. However, accuracy can come from both, a novelist and an historian.” The aim is to show how certain novels can help provide insight into specific battles, in this case the Battle of Gettysburg. I’m working on several other articles to address other novels and other battles. It is a useful way to show how to look at a battle from, hopefully, a different perspective.