Reinventing Beth March

Originally published in 1868, Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women remains a touchstone of classic literature 155 years later. The March sisters, with their diverse personalities, relatable struggles, and timeless dreams, have captured generations of not just readers, but media consumers. In the century and a half since publication, Alcott’s story has been adapted into six films, three live-action television mini-series, an anime series, a Broadway musical, an opera, and a ballet. In addition, contemporary authors like Rey Terciero, Virginia Kantra, and others have reimagined Little Women and its characters as different women in different settings. Kantra splits the sisters into modern-day pairs, focusing on New York City “secret food blogger” Jo and stay-at-home mom Meg in one book and songwriter Beth and “up-and-coming” fashion designer Amy in the other. Terciero makes the March sisters part of a multiracial blended family, focusing a lot of the ensuing graphic novel on racial issues and Jo’s coming out as lesbian.

Whether historical or contemporary, white or of color, straight or LGBTQ+, aimed at adults or kids, every adaptation of Little Women centers on the four March sisters and their unbreakable bond. To this end, their personalities and interests remain much the same. Jo is still the intrepid writer. Meg may not be “traditionally feminine,” but she still probably enjoys fashion or acts “girly,” and if she’s an adult, she probably has kids and is in a traditional motherly role. Amy may still be artistic or drawn to a modern form of art, like gaming or graphic design, and still acts as a typical youngest child–exuberant and charming but also spoiled and selfish. Beth may still be musically gifted, but is often most defined by debilitating anxiety, shyness, or even illness.

These personalities and interests mean that across most adaptations, key events of Little Women follow similar trajectories. That is, in a contemporary setting, Amy won’t get in trouble for bringing limes to school, and she certainly won’t get smacked with a ruler for it. But she could face disproportionate discipline for a minor offense, or run afoul of a teacher whose methods incense Mom, as they did Marmee in the original novel. A contemporary Jo’s writing won’t be denied publication because she’s a woman, at least not outright. Yet she might still face sexism in a male-dominated field or uphill battles in publication if her genre is male-dominated. Meg’s everyday problems as a stay-at-home mom or head of a home-based business won’t look the same as they did for a mother of the 1860s and ’70s. They will likely be more complex, as with an adaptation by Heidi Chiavaroli wherein her youngest son is diagnosed with juvenile diabetes.

But when discussing contemporary adaptations of Little Women, or recent historically-based remakes like Greta Gerwig’s 2019 film, one sister gets left out. Beth doesn’t undergo her sisters’ level of change, their contemporary “glow-up,” so to speak. Unlike the others, Beth’s trajectory remains much the same. Whether this is “needed” is arguable. But it does bring to mind the question of why Beth is the sister denied change, and whether Little Women, or stories that will follow, have room for characters like a “new” Beth. If so, what might she look like?

A Vital, Tragic Commonality

Every adaptation carries one event every Little Women consumer remembers and expects, even if they’ve never read the whole book or seen a whole film. Ask almost any consumer something they remember about Little Women and they’ll likely say, “Beth dies.” It’s a legitimate response. Beth’s death is a poignant moment, particularly in film or onstage, where it’s meant to be “seen.” It’s a major turning point for her sisters, especially Jo, with whom Beth was particularly close. For many consumers, who encounter Little Women around ages 8-10, Beth’s death might be the first human one they’ve experienced “onstage” in fiction. This is in contrast to an offscreen death, or the death of a pet or animal friend (ex.: Charlotte’s Web), which might be sad but carries some detachment because the character was unknown, villainous and, “deserving,” or anthropomorphized, but not human.

Even if a reader is used to death though, Beth March’s death hits hard. Today’s writers are taught to let character deaths make sense for the plot and leave major emotional impacts on readers. Louisa May Alcott does both with aplomb. In her Paris Review article “The Real Tragedy of Beth March,” Carmen Maria Machado explains how Alcott uses “little cruelties and ironies” to foreshadow Beth’s death throughout Little Women‘s first half. These include symbols like “strawberries in winter [or] “castles in the sky,” as well as more overt clues like the death of Beth’s little canary Pip, whom she buries in a domino box. Alcott particularly lingers over this image, describing how Pip’s emaciated limbs seem to stretch, “imploring the food for lack of which he had died.”

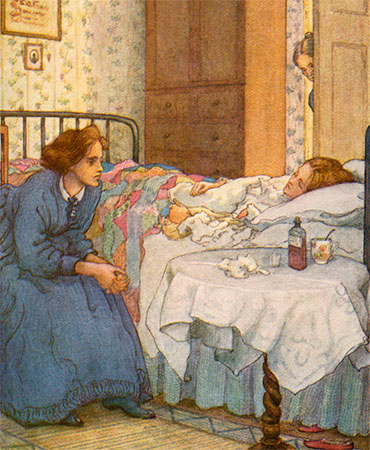

This underscores Beth’s desperate state when, a few chapters later, readers find her wasting away from scarlet fever. Machado describes her condition as “dehumanizing,” “terrifying and gross.” Machado also calls Beth’s condition “creepy,” pointing to Alcott’s description of her talking “in a hoarse, broken voice…[calling] her sisters by the wrong names,” and running her fingers over her blanket as if they were her beloved piano. In other words, Beth isn’t dying quietly and gracefully offstage. She is dying with horrible realism, and readers are spared nothing of the process. They must be spared nothing, Alcott indicates, because sparing them would deny the tragedy of real death. Indeed, although Beth survives her bout with scarlet fever, and although Alcott wrote a version of her novel in which Beth lives, Alcott ultimately chose to keep Beth in the grave. Alcott therefore communicates death is a vital part of life and Beth is not a lesser person for having experienced it sooner than most. In fact, considering 1868 mortality rates, Beth March was probably not alone in her fate.

Angel on Earth or Erased Human?

Yet none of this makes Beth’s trajectory fair, especially in light of her three sisters’ journeys. Based on her overall character, many contemporary readers wonder if that trajectory is still appropriate. That is, Beth experiences a realistic and gritty battle with scarlet fever. But in the second half of Little Women, when she gets sick again, Carmen Maria Machado notes her experience becomes much more Victorian–“beautiful, holy, austere.” Jo ascribes a “pathetic beauty” to her sister, “as if the immortal was shining through [her] frail flesh.” Beth becomes “ethereal,” “[hovering] in the doorway between one world and another.” It seems a fitting, if devastating, end for the fragile third sister, so overcome with shyness and anxiety she couldn’t go to school or greet a neighbor on an average day.

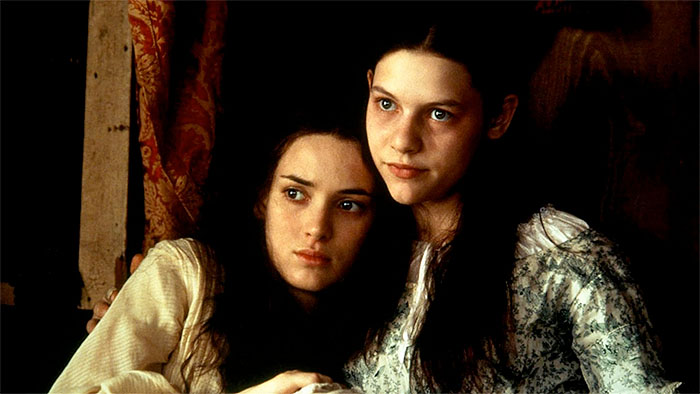

Couple this with Meg’s assertion that Beth is “a dear and nothing else” on the first pages of Little Women, and it becomes clear Beth has always been something a bit more, and less, than truly human. In film, Beth is often portrayed by a “peach-faced” and softly spoken actress, such as Margaret O’Brien in 1949 or Claire Danes in 1994. Her timidity and physical fragility incite protection and coddling from her sisters. Sometimes, even though Amy is the youngest, Beth is treated like their ages are reversed. (The 1949 film actually does reverse the ages).

Beth rarely if ever thinks of herself, to the point of saying her only Christmas wish is for the end of the Civil War and Father’s safe return (a natural desire yes, but notable when compared with her sisters’ wishes for tangibles). She is the first to suggest the sisters spend their Christmas money on Marmee rather than themselves, and the first to suggest they give their sumptuous, rare Christmas breakfast to the Hummels, an impoverished German family from their neighborhood. The other three try to dissuade her in the latter case; Meg notes that “if you…let [starving people] worry you, you’ll never eat at all.” Amy adds she tries not to think about such plights. But coupled with Beth’s altruism, her sisters’ more practical responses come off petty, if not outright selfish. If Beth notices though, she doesn’t let on. She’s content with her self-sacrificing role, to the point of only bringing up her musical interests or desire for a new piano at Jo’s coaxing.

A Posthumous Examination

All this, taken in conjunction with Beth’s eventual demise, leave Little Women’s modern consumers wondering not why Beth died, but maybe why or if she had to. Beth’s characterization, coupled with her death, raises many questions. Beth’s family loves her, but is that because of who she is as a person, or because she is “a dear and nothing else?” Jo, at least, sees Beth as destined for Heaven, but is that because of particular virtue on Beth’s part, or because she was set up to be an “angel,” never meant for this world? Yes, Beth’s death makes sense and stirs appropriate emotion in the reader. Yes, it’s tragic. But was it ever appropriate or “literarily correct?” Is it either of these now, especially in modern adaptations that keep Beth’s death intact? And if the answer to the second question is “no,” where does that leave Beth March and any readers who sympathize or identify with her?

Perhaps in this age of the constant remake, reboot, spinoff, and modern adaptation, Little Women has enough of such treatment. Yet Beth, the sister left behind, still requires justice. Whether justice entails letting her live depends on who’s being asked, but to examine the question, we must resurrect her in some form. Once we do, we can give Beth the full analysis her character deserves. In so doing, we can restore her personhood and examine what a resurrection or reinvention of her should look like, even should she ultimately return to her grave.

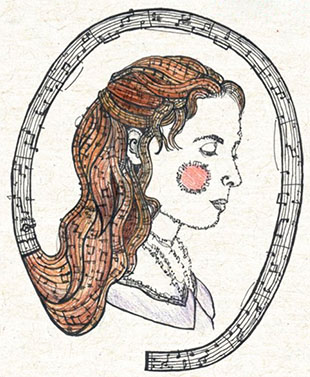

Elizabeth Alcott: The Real, Complex Beth

In resurrecting Beth March, we must start with her roots. Like the other March sisters, Beth comes from a real person, Louisa May Alcott’s younger sister. Elizabeth Sewall Alcott (“Lizzie,” sometimes rendered “Lizzy”), was born March 24, 1835 and died March 14, 1858 at age 22. Like her fictional counterpart, she died of scarlet fever, though Louisa May wrote Beth died of cardiac complications. Also like Beth March, Lizzie contracted the disease while assisting a local German immigrant family.

In some ways, Lizzie Alcott is the “real” Beth in personality, too. In an abandoned manuscript he called Psyche, Lizzie’s father Bronson Alcott made note of his infant daughter’s “relative agreeableness, a trait that had not manifested in his other children.” He wrote Lizzie “[cried] but seldom, often [smiled],” and that “the prevailing temperament of her spirit seems that of repose – deep, still, sustained peace.” In fact, the little readers and critics know about Lizzie Alcott before her illness revolves around her peaceful nature, introversion, and personality built on “faith [and] love.” Bronson Alcott likened her to a sunflower, “[turning] toward the source of the Spirit…even as the sunflower turns toward the radiant light on which it feeds!”

This small bit of Lizzie is the one of the only ones that has endured through the centuries, as opposed to the prolific Louisa and the lesser-known but vibrant May. It is telling, however, that Lizzie Alcott, though she died young, did not fade into obscurity as did her parents or her oldest sister Anna. More information about these three Alcotts exists, but discourse from modern readers and critics reveals Lizzie occupies a bigger slice of consumers’ consciousness. Lizzie’s unplumbed depths, her history, reveal why and help us resurrect Beth’s next layer.

The “Sunflower’s” Twisted Roots

Arguably, Bronson’s focus on Lizzie’s peace and tranquility encouraged her mother and sisters to define her by these characteristics, to her detriment. Long before she was the inspiration for Beth March, Lizzie embodied the inspiration for Psyche to such an extent, the whole family called her “Psyche” for an unspecified period. This was not meant as abuse or neglect, but the family’s failure to give their new daughter a conventional name might have left an impression on her. We don’t know, for example, if Lizzie ever responded to the name “Psyche,” if anyone but her father called her that, what if anything else she answered to, or if she had to adjust once she was christened “Elizabeth” or “Lizzie.”

If little Lizzie’s name were not an issue, her early childhood brings up still more questions. According to Carmen Maria Machado, her father was fascinated with her. Yet Machado doesn’t mention much interaction between baby Lizzie and her mother and sisters. Therefore, one wonders how much of Lizzie’s “peaceful” nature was inborn, and how much was learned. That is, this third child of four might’ve learned the best way to get her needs met was to avoid attracting attention and, when she had attention, behave agreeably. That way, her busy family would meet her needs next time.

Machado goes on to explain that unlike with his other daughters, Bronson viewed Lizzie almost as a spirit child–rather like her sisters view Beth in Little Women. Beth is described as “a dear and nothing else”; her mother’s “cricket on the hearth”; a “regular snow maiden.” Bronson Alcott describes Lizzie’s every movement in terms like, “[prayers] of aspiration; her breath of life, an ascription.” He writes of Lizzie stretching her tiny arms “forth toward that nature on which she now relies for that sustaining influence.” He even ascribes to her a preference for summer, long before she can express such a thing. To Bronson, Lizzie is not just a “tabula rasa,” a blank slate like all children. She is the daughter upon whom Bronson projects all his Transcendentalist philosophies and ideals in their most unfiltered forms.

Bronson Alcott probably wasn’t conscious of this. Machado admits, “I’m being unfair to Bronson” in her analysis of Lizzie Alcott and Beth March. He was only doing what any parent tends to do with a new baby. “We adore imbuing newborns…with emotions and reactions that make sense to us,” Machado writes. And yes, it probably wasn’t out of line to think of Lizzie Alcott as what we call a “sweet summer child” today. As she grew older, it might’ve made sense to ascribe a certain personality type to her, like an Introverted, Feeling Meyers-Briggs type. It might’ve made sense to call her a “spiritual” child or encourage her in pursuits that let her help or heal others. The problem for Lizzie, and later Beth, is the degree to which Bronson Alcott let himself project his beliefs onto and live vicariously through her. Once Bronson’s emotions, coupled with Lizzie’s natural bent, were ascribed to her, she had no room to become anything or anyone else.

This trajectory continued and deepened in Lizzie’s relationship with her older sisters Anna and Louisa. Again, not much is known about Lizzie’s childhood or teenage years. However, small anecdotes have survived. Machado highlights one from when Lizzie was a toddler and her sisters built a tower of books around her as part of a game. “Lizzie was so agreeable about it, they kept going until she was nearly concealed,” Machado writes. When Anna and Louisa lost interest, they wandered off, and no one noticed Lizzie was missing for ostensibly hours. In her journal, Louisa writes the family found Lizzie “asleep in her dungeon cell,” and that she “emerged so rosy and smiling from her nap that we were forgiven for our carelessness.” Although Machado notes “there are many ways to read this story,” one cannot help noticing how Louisa praises Lizzie for going along with being forgotten. One could even argue Louisa engages in victim-blaming, because her subtext reads, “Of course, we wouldn’t have been so careless had Lizzie made herself known.”

A Dark, Rich Center

It might seem a stretch to say the book tower incident locked Lizzie Alcott into an archetype or otherwise marked her for life. After all, the most attentive family and biggest friendship circle in the world couldn’t prevent her death. This is particularly true in the absence of medical advancements like vaccines, antibiotics, nutritional availability, and mental health techniques that would’ve helped with conditions like social anxiety. Before we write off the book tower incident or Lizzie’s childhood though, we should look at the only other part of her life given any attention – her illness. Remember, Lizzie contracted scarlet fever in 1856, at age 20. Thus, she never progressed far past adolescence. Her childhood and adolescence contain the only events that could shape her, and therefore, the only ones that could create and influence Beth March.

The “scarlet fever layer” of Lizzie Alcott then, becomes the most vital to Beth’s resurrection and possible reinvention. Just as scarlet fever itself didn’t kill Beth, it didn’t kill her inspiration. Fever appears the root of Lizzie’s demise, but Machado writes her final diagnosis was “atrophy or consumption of the nervous system, with great development of hysteria.” In other words, Lizzie’s 1850s physician probably diagnosed her not only with legitimate scarlet fever complications, but also any number of ailments considered “female-only.” These could range from “a wandering uterus” to “psychological symptoms [and] erotic suppression.” Lizzie would’ve been prescribed complete bed rest and abstinence from “all physical and intellectual activity.” This would have cemented her position in family and society as “an invalid,” and ironically sealed her fate to die young, younger even than her era would normally dictate for a woman.

Readers’ portrait of an ill Lizzie comes mostly from her sister Louisa’s journals. There, she is described as a “shadow,” language also used to describe Beth during her second bout of illness in Little Women. But unlike Beth, Lizzie did some writing of her own during her second illness. Most of it has been lost, but a few letters to her family do exist. In those, she makes some “wry, dark” observations that contrast sharply with both Louisa’s “shadow” language and Jo March’s “Victorian…pathetic [beautiful]” description of Beth’s death. Lizzie, for example, writes of shocking a “saucy” woman who inquired if she was an “invalid” by simply staring back at her, in all her ill glory, from a carriage window, She describes “[eating her] chicken with relish…troubling [herself] about nobody” and calling a nurse of hers an “old cactus.” Lizzie implores her family to “write often to their little skeleton” with a mix of tongue-in-cheek humor and crackling sarcasm. She knows she has been sent away to “convalesce” with little hope it will actually work. She knows she’s going to die; she knows her death is the culmination of what little influence she has ever had on her family.

A Flower (Almost) Crushed

Lizzie Alcott accepts the brutal truth, not with complete anger and bitterness, but not with the superhuman selflessness of Beth March, either. Machado acknowledges Lizzie died “angry at the world,” but cares more that this woman was “snarky and strange and funny and kind.” She declares, “Lizzie’s family had a narrative about her, and it killed her.” Indeed, whether the Alcotts meant to “kill” Lizzie, or turn her into some “Pollyanna-ish” angel, cannot be proven. The most we could accuse them of today is child abuse or neglect, and as with illness or anxiety, that was treated very differently in the 1860s and ’70s as opposed to now. The little we know of the Alcotts indicates abuse or neglect wouldn’t have been intentional, anyway.

What we do know, however, is how Louisa shaped the characters of Beth and Jo March in light of Lizzie’s death and her own trauma. If she ever observed Lizzie’s wry humor, snark, or strangeness, Louisa chose to write it out of Beth. In place of those traits, she created the angelic figure we know from Little Women, “a dear and nothing else,” who “chatters on” about virtue and mercy when she talks at all and acts as “a force for good” within the family. Beth supposedly has moments of imperfection, such as when she lets her beloved canary Pip die of starvation during a period when Marmee lets the girls forego their chores. Yet Machado and other critics note these moments are so fleeting, they read more as Louisa “[paying] lip service” to Beth being human. Taken with the clues that foreshadow her death, they malign Beth as too perfect more than redeeming her as relatable.

But like Lizzie’s, Beth’s “rich center” isn’t completely crushed. A close reading of Little Women reads as if some of that center fights for survival and a voice, no matter how hard Louisa Alcott tries to write it out. That fight is clearest during Beth’s second bout of illness, during which Jo becomes convinced Beth has a great secret. At first, Jo believes said secret is “unrequited love.” She attributes Beth’s pallor and listlessness to longing for Laurie Laurence, perhaps out of a mix of denial and hope that if Beth loved a man, any man, she might rally and become well. Soon though, she learns the truth. Beth’s secret is, she always knew deep down, she was never intended to live long. She couldn’t picture herself fitting in anywhere but at home. In the 1994 film, Beth expands on this, saying, “I was never like the rest of you, making plans about the great things I’d do…I’m not afraid…now I’m the one going ahead.”

Because Little Women, in all its adaptations, is seen mostly from Jo’s point of view, Beth’s “death speeches” like the one above are often read as resignation. Beth is “too good for this sinful earth”; she’s too shy and anxiety-ridden; she doesn’t have plans and goals that will fit “the real world.” But a close read indicates Beth is more like her inspiration Lizzie Alcott than the character could ever be or her traumatized author ever knew. In declaring she knew death was imminent, she doesn’t fear it, and in a way she prepared for it, Beth sets herself on equal footing with Jo, Meg, and Amy. She is not the poor little sister who couldn’t make it. She takes control of her destiny as much as her sisters did. She simply does so in a different, more ethereal, more eternal way. Beth also decides how she is going to meet death–as she did life. She will not show anger as Jo or Amy might, or as Lizzie Alcott did, but she will show quiet determination and fearlessness. That fearlessness will declare, “This does not detract from, or end, who I am. This is part of who I am.”

A Beth for the 21st Century

Resurrection, Creation, or Both?

Where, then, does the “old,” “classic” Beth March leave today’s consumers? Our posthumous examination of the classic Beth and her inspiration have revealed she and her story are complex enough that death could still be a satisfying ending for her. The landscape of the 21st century though, may not support a Beth March whose complexity can only be found under such scrutiny. If Little Women and similar stories such as prequels, sequels, and various modernizations, are going to continue in relevance, Beth needs as much a chance to thrive as the other three sisters receive.

Creators should be careful with Beth’s “update,” though. Letting her thrive does not simply mean, “Let her live and otherwise leave her alone.” Treating Beth with the respect she’s been denied means giving her development and storyline equal footing with her sisters’. Ideally, this entails both resurrecting and re-creating her character. This would be a painstaking process, as it would require balance the other three March sisters arguably do not need when re-creating their characters. Failure to balance at one end of the “scale” or the other would lead to some major pitfalls. These would not only cause the creator to lose modern consumers, but would cause further disrespect to Beth’s character and the entire March family. Worst of all, it might cause longtime devotees of Little Women and the Marches to lose faith in, and love for, one of their favorite stories.

Resurrection Without Re-Creation: Saccharine and Overdone

Stuck in a Mold

Many current updates of Little Women handle Beth’s character through resurrection without re-creation. That is, they bring Beth “back from the dead,” but only to reenact the same story over and over, as with the modernized 2018 and most recent historical 2019 films. Failing that, updates resurrect Beth, but only let her play the same character consumers are used to seeing.

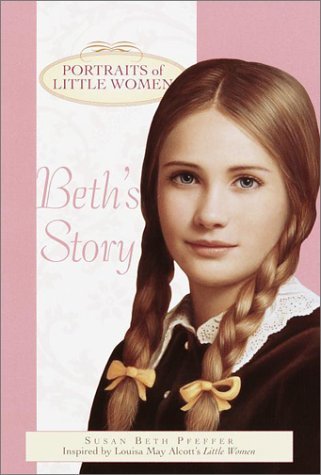

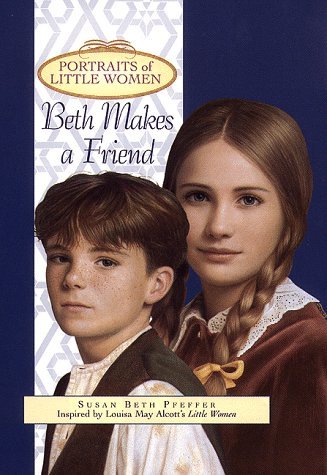

Several prequels and offshoots are guilty of this, particularly those aimed at young girls who enjoy the original story and want to relate to the March sisters on a deeper level. One older, but still well-regarded series that lets them do so is Susan Beth Pfeiffer’s Portraits of Little Women. Popular in the mid- to late 1990s and early 2000s, this series of small, pastel hardbacks began as a quartet of stories. Each story starred a March sister at age ten, experiencing a coming-of-age plot. The initial stories became so popular that they spawned offshoots, such as stories where each sister made a friend outside the family and had another coming-of-age moment, as well as omnibuses centered on Christmas, Halloween, and birthdays.

This writer remembers reading several of the Portraits stories, and choosing to read Beth’s first because she wanted to know what this character was truly like before her illness and death. Beth does have some interesting adventures during the series. Her first installment, simply titled Beth’s Story, has her sisters vote that she be the one to accompany Marmee and Father on a trip to Washington, where she gets to meet the not-yet-President Abraham Lincoln. Beth Makes a Friend has her meet immigrant Sean O’Neill, which gives her a realistic outlet for all her “angelic” kindness. And “Beth’s Christmas Dream,” her story in the Christmas omnibus, has Beth confront the reality that while she may think otherwise, the world actually would be different, in a negative sense, if she did not exist.

All these stories do a great job of resurrecting Beth March and giving her more to do than be her sisters’ “force for good,” act almost perfect, and then become ill or die at the first opportunity. As with the original character though, the key to resurrecting and re-creating Beth is close reading, and a close reading of these updates reveals some significant problems. Namely, Beth has more to do, but it’s more of the same.

Beth’s encounter with Lincoln is set up as a way for her to “overcome” her shyness, the way a modern physically disabled character might be said to “overcome” blindness, deafness, or cerebral palsy because they participated in an athletic contest or went on a trip. But the argument there is, should Beth have to “overcome” shyness to feel “acceptable” to someone else, and to what degree? Should she have to, for example, set a goal of becoming as comfortable with public speaking as Lincoln apparently became? Not to mention the fact, the next time we see Beth in Amy’s story, her timidity seems back to its previous level, and no one gives it much thought.

Beth’s friendship with Sean O’Neill and her Christmas dream follow similar paths. That is, knowing Sean makes Beth more aware of how immigrants live, which gives her a concrete outlet for a natural charitable nature. However, this devolves into what today’s psychologists call “scrupulosity.” Beth is continually confronted with the O’Neills’ desperate situation and feels like she can never do enough, so she schemes to steal from Aunt March. She never actually does it. She and Sean persuade Aunt March to use her resources to help the local immigrant population as a whole. But this places Beth squarely back in “too good for this sinful earth” territory. She’s more a martyr than a help. Her efforts aren’t effective, and everyone else is so focused on what a “dear” she is, they seem unaware of whether she’s mentally healthy. Similarly, when Beth wakes after her Christmas dream, Marmee acknowledges that dreaming one doesn’t exist is a nightmare. She then enumerates how and why Beth makes the family better. But she focuses more on Beth’s deeds–“You keep Jo calm…your very presence prevents Amy from being spoiled,” than who Beth is as a person. Therefore, Beth has no chance to break out of her family’s mold.

Constant Foreshadowing of Death

This problem persists when Beth is not the focus of a Portraits story as well. It’s most prominent during stories focused on Jo, with whom Beth has the closest relationship (somewhat mirroring Louisa and Lizzie in real life). The original Jo’s Story, for instance, has Jo overhear a conversation between Marmee and Aunt March during which the latter offers to take one of the March girls to live with her. Jo overhears only part of Marmee’s reply, not knowing it’s the beginning of a polite but pointed refusal. She then goes into deep, angst-ridden introspection about which girl should live with Aunt March.

When Jo considers Beth, she finds the younger girl has many points in her favor. Beth is quiet, and Aunt March prefers a quiet house. Beth is extremely compliant and would learn anything Aunt March asked of her. Though under ten at this point, Beth already keeps house well for her age and knows how to act like a “proper little lady.” Aunt March would also find Beth’s piano playing both soothing and charming. But, Jo notes with fierce protectiveness, Aunt March would also refuse to tolerate Beth’s intense social anxiety. She might force the girl into potentially traumatizing situations and discipline her harshly for “failure.” Jo also realizes Aunt March would take away Beth’s treasures, her “collection of woebegone dolls,” because they’re all missing limbs or digits or heads. “Everything was perfect at Aunt March’s,” Jo remembers with chagrin. On top of all this, Beth would likely comply, despite personal heartbreak. This isn’t outright stated, and a target audience member might not catch the implication, but a discerning adult reader might wonder–would such a situation kill Beth, emotionally if not physically? Was Susan Pfeiffer foreshadowing, if unconsciously?

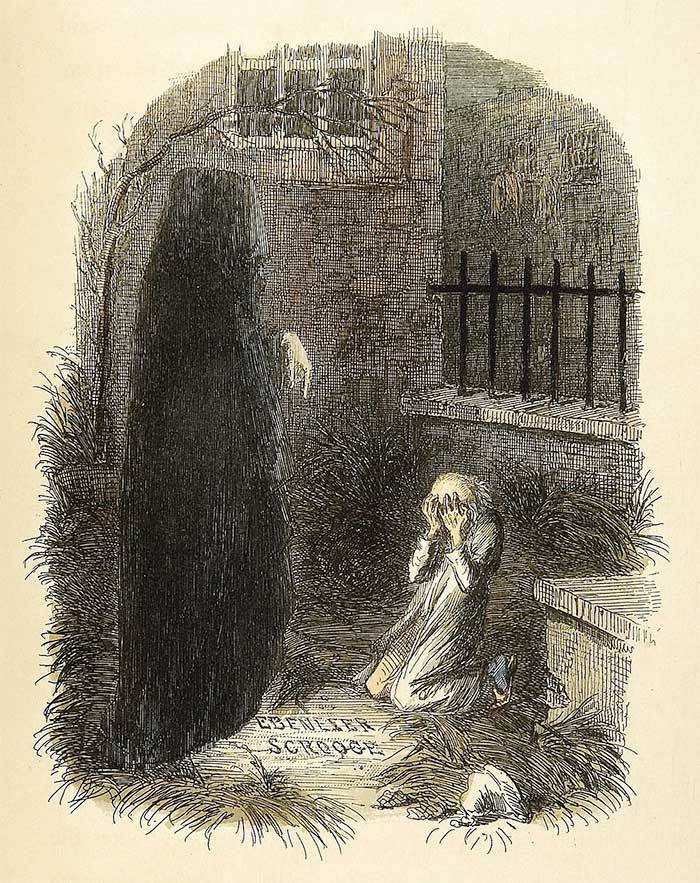

Such foreshadowing pops up again during “Jo’s Christmas Dream” in the Portraits Christmas omnibus. Within the story, the stress of the holiday, plus a confrontation with Aunt March and a case of writer’s block, has left a newly pubescent Jo unusually snappish and surly with her sisters. When she goes to bed that night, she’s thrust into a dream reminiscent of A Christmas Carol, wherein three spirits show her Christmases of the past, present, and future. The third spirit, dressed in the requisite hooded cloak, is Beth as Jo knows her right now, her younger sister about age eight or nine. She shows Jo a Christmas several years in the future, presumably the canon Little Women timeline.

Readers are meant to focus on Jo’s possible future in this timeline–her projected family greets her coldly and dutifully and calls her “Aunt March,” because her temper and aloofness have made her the new Aunt March with whom they dread spending time. Indeed, Jo learns the expected lesson from the dream and makes up with her sisters as soon as she can upon waking. But it’s impossible to miss a crucial detail. Still within that dream, before realizing that she’s Aunt March, Jo asks Beth, “Where are you?” The grown-up versions of Meg and Amy are there, as are an older Marmee and Father and some presumed grandkids, nieces, and nephews, but where is Beth? Beth immediately answers, “I’m not there that Christmas,” but with only a hint of regret. She quickly moves on, refocusing Jo and glossing over the implications.

Pfeiffer could have done this for a number of reasons–to prevent spoilers, to protect precocious but still sensitive readers, or to refocus readers just as Beth does. But foreshadowing still exists, and so Beth remains the resurrected character who stays stuck in the role of “sister who will die.” She’s resurrected, but not given a chance to move or develop. Readers are meant to pity her or think she’s sweet, but not think beyond that. Thus, Beth’s arc remains saccharine, with hints of disability or illness-based inspiration porn. Once again, she is resurrected, but not re-created. She remains alive, but the focus stays on her eventual death. Even if young readers don’t know Beth’s fate, they may well figure it out considering the references to canon in the Portraits series. If not, it’s a safe bet they would easily understand and accept Beth’s death when they saw it in Little Women proper, either the book or a film. Perhaps those young readers would accept it too easily.

Re-Creation Without Resurrection: Melodramatic and Cliche

The other option for modern creators who want to re-create Little Women is to let the third March sister live. It’s a popular choice as evidenced in works by Virginia Kantra, Heidi Chiavaroli, and Bethany C. Morrow. Considering our access to modern medicine, as well as our awareness of how to represent chronically ill or disabled characters, keeping Beth alive arguably makes more sense than retelling the story or placing her in a new or modernized one just so she can die again at some point. Yet, the authors who’ve chosen re-creation for Beth have also forgotten to resurrect her first. That is, they have remained unaware of, or completely ignored, her roots as the March sister who was both denied a full life and took ownership of the one she had.

These authors cannot be blamed for not knowing the complexities of the real Lizzie Alcott, or not knowing about the trauma Louisa May Alcott suffered at losing her sister. They cannot be blamed for taking Louisa’s template of the sweet, “stupid little Beth,” as the character herself says, and turning it into a template of a still introverted, yet more assertive, modern woman. Few of today’s readers will stand for an authentic “angel in the house” if she comes from the 21st century, particularly if she’s also ill or disabled. That plays into stereotypes. What authors who re-create Beth without resurrection should answer for however, is the creation of a modern Beth whose roots are used for others’ growth, or to push messages about the problems today’s heroines should face. When that happens, it becomes melodrama, and Beth becomes something worse than an erased “angel” or a crushed flower. She becomes a boring, cliched character who consumers might argue wasn’t needed.

Connected, But a Castoff

If Beth lives, she does retain many of her “roots” as a character. Her shy, introverted personality stays the same, although her anxiety isn’t as life-altering as in Little Women. In Heidi Chiavaroli’s Where Love Grows, for instance, Beth becomes Lizzie Martin, who struggles with things like taking food orders at her family’s bed and breakfast but enjoys working there, and loves her second job teaching music at a local school. In Virginia Kantra’s Beth and Amy, our heroine still goes by Beth March and is “a talented singer-songwriter,” though she finds the idea of actually touring with anyone horrifying. New incarnations of Beth also retain her bent toward charity and patience, though they aren’t as all-encompassing or “perfect” as in Little Women. Lizzie Martin nurses misgivings about dating a man who uses a wheelchair; the Beth March of Beth and Amy hooks up with and risks getting pregnant by a country star who may or may not be abusive. A re-created Beth has also usually struggled with illness before if not in the story proper. Modern authors have had her face everything from thyroid removal to anxiety-linked gastrointestinal issues to anorexia and bulimia. The modern Beth March, these authors communicate, has sweet “sunflower” roots but definitely possesses an edge.

A re-created if not resurrected Beth March stays connected to her family, too. Again, she’s not as connected as the original Beth, because today’s stories demand a “new” Beth create her own friendships and relationships, ill and introverted or not. Still, whether she goes by Lizzie, Beth, Bethlehem (in the case of Bethany C. Morrow’s So Many Beginnings) or something else, Beth remains a source of “glue” for her parents and sisters. She still awakens a protective instinct in the older sisters especially; Jo still calls her “Bethie” in Virginia Kantra’s duology. She remains closest to home or struggles with homesickness if she’s let herself leave for any length of time. If she doesn’t travel, the Beth character shows the most comfort indoors, behind a screen or drive-through window, or interacting one-on-one with people she doesn’t know well. She relates to non-family based on her core interests, notably music.

The modern Beth character has so much in common with her inspiration, consumers would expect her to be a vibrant, three-dimensional addition to a modern retelling or adaptation. Oddly though, these commonalities make Beth feel like more off a castoff in stories where she should finally be the heroine. Where Love Grows, for example, focuses not on Lizzie Martin, but on her romance with Asher Hill, a former star athlete who now owns a chain of sports stores and uses a wheelchair. Since Beth is the only March sister who doesn’t get a love interest in Little Women, giving Lizzie Martin a romance is a fine idea. But Lizzie’s love story is not one, at least not for her. It focuses more on whether she can learn to love “a man in a wheelchair,” and if yes, how she can help Asher see he is worth loving “with or without a wheelchair.”

In other words, Lizzie becomes disconnected and cast off in her own story because she’s not there to play a central role. Like the original Beth, she exists to help someone else find and live in their value. Asher does help Lizzie mount a songwriting career, but only because she restored his self-esteem first. Their romance reads not as a mutual relationship. It is one in which Asher is inspiration porn and Lizzie is a willing conduit, marginally more fortunate because despite thyroid surgery at fifteen, she is considered able-bodied.

A similar breakdown happens in Virginia Kantra’s Beth and Amy, and not because Beth receives only half the book’s attention. In Kantra’s case, her Beth could be a fully resurrected and re-created version, if not for the handling of her illness within her present life. In Beth and Amy, Beth’s illness is not a defining, tragic event as in Little Women or a few modern adaptations including Terciero’s graphic novel, wherein she succumbs to cancer. Instead, Beth starts off experiencing gastrointestinal problems as a teen when her dad deploys to Iraq. At first, these are linked to severe anxiety. Over time though, Beth discovers comfort in the sensation of vomiting, calling it a “friend” and seeing it as something she can control. The vomiting takes her down the road into anorexia and bulimia. She’s in some form of recovery by the outset of Beth and Amy, but has slipped back into covering symptoms as she did before treatment.

Coupled with severe stage fright, and the fact that her eating disorder is pretty much the center of her arc, Beth’s illness and anxieties define her almost more than the original Beth’s death did. Many reviewers complain about this, citing the fact that any dialogue involving Beth comes down to someone asking about her illness and Beth insisting, “I’m fine” over and over.

Arguably, this is in line with her character template. Beth is still the selfless sister of her quartet. But such focus, combined with Beth’s denial that anything is wrong, her not-so-well hidden problems with her country star boyfriend, and her social anxiety, make her look more like a stereotypical “hot mess” heroine than a nuanced, modern March sister. Beth has physical life, a job, and a boyfriend, but once again, she fades in the shadow of a sister who is “well,” and physical and mental troubles that by their very nature are bigger than she can handle. She is connected only because without her family, she cannot survive, despite the trappings of an independent woman.

Doted On Without Depth

In the stories where Beth lives, she is not “a dear and nothing else,” as Meg infamously said. The 21st century Beth, Lizzie, or Bethlehem gets more of a voice than her historical counterparts ever did. Heidi Chiavaroli goes so far as to use first person for her in Where Love Grows. And certainly, since most Little Women updates are genre stories–graphic novels, adult or young adult romances, race- or gender-bent novels–it might not be fair to expect deep, “literary” voices. With that said, a re-created yet not resurrected Beth is incomplete precisely because the depth of her resurrected voice is missing. The underlying messages of fearlessness and facing destiny, with or without having done “great things,” that the original Beth March gave consumers, are gone. Beth remains the sister most doted on and protected, but in today’s stories, there’s no depth to that protection or love.

The lack of depth comes through clearly in Virginia Kantra and Heidi Chiavaroli’s books. It’s arguably more obvious with Kantra since in Beth and Amy, the spotlight is on Beth while she is actively ill and trying to hide her symptoms. Thus, it would make sense for her family to worry over and dote on her. Since they are the only people she has ever “let in” to her inner world, the dynamic works on a deeper level. But once Beth tells Amy, Jo, or someone else she’s “fine,” her thread is dropped until her next chapter. Beth’s arc becomes a push-pull dialogue where nobody moves off square one for much of the book. It’s more egregious when we learn Amy thought Beth was “faking” when she first experienced stomach issues as an adolescent. Granted, Beth is not as close to Amy as to Jo, then or in the present story. But readers are left to wonder, if Beth felt she couldn’t trust the sister closest in age with the truth, did that contribute to her need for safety and control via eating disorders? Moreover, how much has Amy’s initial lack of belief, plus the family’s detached doting, driven Beth further into her current state?

Heidi Chiavaroli takes a “softer” tack, but gives her re-created Lizzie Martin no more depth than Kantra’s modern Beth March received. From chapter one onward, it’s extremely clear Lizzie is the most protected Martin sister. Her mom asks her to wait tables at the bed and breakfast, but her tone communicates, “It’s okay if you don’t want to, or if you ‘fail’ at doing it.” Since we’re in Lizzie’s point of view, we see that this cements her social anxiety. She angsts for several paragraphs over how much easier the job would be if she were poised like oldest sister Maggie or highly verbal like next-oldest Josie, or charming like Amie. Later on, we do see Lizzie succeeding socially–to a point. But when those interactions set up conflict–for example, when a talk with her supervisor reveals her school’s music program, therefore Lizzie’s job, will be cut–Lizzie’s family doesn’t directly speak to her ability to handle it. Her sisters, especially Josie, try for encouragement. As with Mom though, it comes across more as comforting Lizzie through anxiety and treating her as fragile. Like the real Lizzie Alcott, Lizzie Martin hasn’t been allowed to move past her anxiety or illness in a significant way. Thus, the fragility she’s still entitled to, doesn’t get the respect or gravitas it deserves.

What Would the “Best” Beth Look Like?

Having analyzed several portraits of Beth March and her “descendants,” we have a sense of what creators should not do. However, if Little Women remixes are going to continue, which seems likely in an age of so many, how should new creators treat Beth? The answer to this question seems simple, yet has more facets than might be obvious.

A close reading of Little Women is a must, with particular attention to Beth’s major scenes and the clues that foreshadow her death. As we have seen though, a close reading is not nearly enough to create a truly three-dimensional Beth, because Little Women was written in a time when ill, disabled characters, especially females, were treated much differently than today. Along with the close reading, creators would do well to examine narratives of characters who are similar to Beth, but who were first written for a 21st-century audience. Characters who stay alive are absolutely necessary, but can also be studied in conjunction with characters who succumb, if they are strong protagonists. Examples could include John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars, Delia Owens’ Where the Crawdads Sing, and Lillie Lanoff’s One for All. These and other novels feature young women living with everything from cancer to extreme introversion to Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS). Death is a risk on some level for them all, if not from illness, from outside forces such as nature or actual villains. These external forces allow any disability, illness, or inner fragility to be a part of the young woman’s authentic self, not kill her outright or be “overcome.”

Creators seeking to resurrect and re-create Beth should also seek out the voices of real readers who identify with her. This might seem difficult at first, as many Little Women readers identify with Jo or Amy, or outright choose to do so whether their personalities align or not because Meg and Beth seem more “traditional” or “boring.” However, plenty of Beth fans do exist, and their voices are becoming stronger. In her Huffington Post article “Wanting to be Beth March,” Claire Fallon writes she wanted to be Beth because she “wanted to be really, deeply, effortlessly nice…saintly instead of selfish.” Fallon goes on to say wanting to be Beth is “wanting to be like Jesus” in a way, because unfortunately for Beth, who’s supposed to be human, she never does anything really wrong. Thus, she becomes a reminder that imitating her is like imitating Jesus–“you’re always going to come up short.” Fallon also admits she wants to be like Beth because it means she would be “never in the wrong,” which isn’t realistic.

Still, if we make the desire to be a saint, “devoid of ambition…a homebody…too good to live,” more reachable, we can see why Beth is still an embraceable role model. She’s honestly, guilelessly kind. She sees the good in everyone while judging no one unless they are unrepentantly wicked. She has deep interests of her own–music and healing, if we go by her doll collection–but isn’t self-absorbed in those. With a deft hand, it would be entirely possible to create a Beth who is and does all these things, who is still a believable “angel in the house” because she loves her house and family. The creator would not have to sacrifice her personality or ability to shape her destiny.

Finally, today’s creators should be careful not to throw out all the 21st-century portraits of Beth March. They are flawed, in that few if any come close to the creation of a fully realized Beth. Yet all of them contain pieces of the character Beth could, arguably should, become for the next generations. For instance, Louisa May Alcott’s original work with the foreshadowing of Beth’s death, as well as her initial foreboding descriptions of Beth with scarlet fever, are clever and harrowing. These could easily get smart modern twists, particularly for creators interested in Gothic or Victorian settings, mysteries, medical dramas, or even horror stories.

Virginia Kantra and Heidi Chiavaroli’s ideas of Beth as a songwriter or singer are wonderful ways to handle Beth’s musical talent, if a bit heavy-handed. A creator could “pull back” on it so that Beth doesn’t need to “overcome” her introversion or illness by being famous, but does still have a comfortable and fulfilled life based on that talent. Susan Beth Pfeiffer’s adventures for Beth, penned across Portraits of Little Women, could provide fodder for a modern Beth’s internal stakes, either during or after illness or treatment. For instance, what might happen if she wrestled with the question, “Why do I exist and does it, has it ever, mattered?”

A New Beth’s “Finishing Touches”

When today’s readers or viewers think of Little Women, Beth March isn’t the character who usually comes to mind. She’s most often remembered for her heartrending but tragic and untimely death. Most consumers quickly move away from that moment in their minds, eager to focus on the “stronger,” more empowering arcs of Jo, Amy, and even Meg, who though she remains a housewife true to her era, does live through the entire saga.

However, those who dismiss Beth, including 21st-century re-creators and arguably Louisa May Alcott herself, have done this character a great disservice. Granted, Beth March is not an easy character to resurrect or re-create. The constant focus on her illness and intense anxiety have left her inked in readers’ minds as what Claire Fallon called “timid [and] devoid of ambition,” easily maligned. But those willing to delve into Beth’s history and look at her more closely will find a much more complex young woman hiding beneath the wings of the “angel” her author, and generations of others, have created. Beth March is a merciful, guileless person, it’s true. She’s also a young woman who dares to remain humble and selfless in an increasingly selfish world. She accepts and faces death with quiet fearlessness, despite her stronger sisters’ distress. These and other hidden depths deserve the best resurrection and re-creation they can receive.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I just finished reading this, and I must say it’s one of the most comprehensive and insightful pieces I’ve come across on the subject. You have done an excellent job in delving into various aspects of Beth’s character, providing a deep analysis of her personality, role in the story, and the impact she has on the other March sisters.

Your article beautifully highlights the complexity of Beth’s character, her gentle and selfless nature, and the profound effect she has on the overall narrative. I truly enjoyed reading your piece; it was both engaging and informative. Your writing is clear, and your passion for the subject matter shines through.

Additionally, your article has piqued my curiosity about the Korean adaptation of “Little Women.” I’ll definitely be on the lookout for that adaptation and see how they interpret the character of Beth in a different cultural context.

Kudos to you for this excellent work, and I look forward to reading more from you in the future!

Briefly:

I thought Beth lived on through Meg’s two daughters.

Daisy and the much younger daughter Bess.

***

In the Wikipedia article – Lizzie was first named after a teaching assistant – and when Bronson had a falling-out with that assistant – she was given the name which we know her by today.

***

And I never thought of Claire Danes as peach-faced!

***

Some of Beth’s roles remind me a lot of Emily Bronte as a person – like the housekeeping and her love of animals – and her immersion into the imaginative life.

Beth was my favorite. I was reading the book and my friend spoiled it for me, this took place at school and I almost burst into tears. I still cry about it.

This made me sad as a child reading the book.

When I first read the Little Women series, I HATED Louisa (the author) for Beth’s death. I mean, I was like…how could she do such a thing to her? But then, as I grew older and learned more of life, family, and reality, I understood why Louisa did it – loss is a fundamental part of life, something that each and every family had to deal with sooner or later, and things can never be 100% perfect, and I think that was what Louisa was trying to tell everyone through Beth’s death. Also, as heartbreaking and even unspeakable as it was, Beth’s death was a major part of what helped her sisters – especially Jo – to grow and mature even further, an evolution as well as an understanding that they could not have achieved without this tragedy. Rest in peace, Elizabeth March. Gone but never forgotten.

In the real novel Beth didn’t die it’s just the movie.

Little Women is actually based on Louisa and her sisters. Beth was based on Louisa’s sister Elizabeth (Lizzie) Alcott who died at the age of 22. Everything that happened to Beth in the book (& movie) happened to her in real life. The real Beth cought Scarlet Fever from the German family that she was helping, it weakened her heart and she died of heart failure the next year. So this isn’t just a story, this is history.

It’s based on her own sister who passed away.

Claire Danes portrays Beth perfectly in 1994 adoption; the awkward, introverted shyness but the deep and loving affection she has for her family and others. Even the timbre of her voice in this scene is so well performed; with the wavering sadness but sure acceptance of her impending death, with just that raspy hint of wheeze and breathlessness to hint at the congestive heart failure brought on by the scarlet fever.

I think that she showed how under all the shyness Beth was fiercely brave, brave enough to conquer a real life battle which was different from the one’s in Jo’s stories.

Wow, that’s beautifully put; yes, I agree! And that she was able to live her life with absolute certainty in her choice and desire to stay at home, in vast contrast to her three sisters.

I have the book, and Beth doesn’t die…. If the book says “she doesn’t die” so SHE DOESN’T DIE!

I appreciate how 2019 movie is structured, but in some ways, lumping together Beth’s illness/scarlet fever, Christmas, and death all into one scene diminished the emotional weight of those scenes. It was still impactful, but some of it felt rushed and emotion lost.

I must say that I agree. Although when I think about restructuring it in my head, it feels off. This scene on its own still never fails to make me cry, though.

Beth is the sweetest girl that’s why jo loves her so much.

Yes! I always loved their sisterly bond. Jo and Beth can seem like such polar opposites sometimes, but that’s also why they seem to balance each other out so well.

Greta Gerwig, amazing director, damn you for making me cry.

I always thought the portrayal of Beth was interesting in how saintly she was, very much the angel figure that the other sisters wish they could be like, but less of a well-rounded character as a result.

I really enjoyed it and definitely want to get the full book now!

I never liked Beth (even as a child when I first read the book). She’s too agreeable. I was mad when we had to get rid of my cat when he kept triggering asthma attacks, why was Beth never angry at her circumstances?

Thank you. I have always related to Beth March the most from Little Women. And now that I have a chronic illness even more.

As I’ve gotten older and sick, I can definitely relate to Lizzie’s anger and raging at the world for her predicament. Having negative emotions over being sick, instead of a Pollyanna attitude is far more realistic but people always want us to have a Pollyanna attitude.

Beth has always been my favorite of the March girls because I identified with her, too. Timid and quiet but still had so much to offer.

I love Beth. I love how no matter what she is kind and gentle. Even when she is sick she helps the school kids and sends her supplies down to them. She always worries more about her family. Beth doesn’t care what happens as long as her family is safe. She is amazing and I cried when I read Little Women and then I cried again when I read it the second time.

I totally agree! Love Beth.

She was my favorite March girl when I was growing up, because I related to her. She’s quiet and shy, but still waters run deep. I also loved her relationship with Jo, and wished for a “Jo” of my own (I was the eldest child).

I read the Finnish translation, in which the two books are separate. Beth didn’t die in the first book, Little Women, she died in the second book. I never knew that these two were published as one book in America.

Beth is a bit snarkier in the latest film adaptation.

She is such an angel.

Beth was such an angel. She deserved to live… but then again I suppose the best people are always the first to go…

I know! Beth is my fav sis but she is so underated.

If she lived the emotion of her string character wouldn’t last it was a good decision to cut her off to add feeling emotion reality.

Greta Gerwig’s parallelism of the beth and her sister was just perfect. It was really hard to fight down the tears.

Nothing hits harder than in the 90s version when Beth tells Jo she’ll be homesick for her even in heaven.. that whole scene Claire Danes was amazing at it.

That line just breaks me every time.

I remember sitting in a cinema and watching the movie with my Gran when it first came out. She loved this book as a child and i remember her handing me a tissue because we were both crying so hard. She passed away quite suddenly about eight months ago so beth’s christmas scene really hits close to home now.

This scene was so heartwarming (between the two depressing scenes) their father coming back and me waiting the whole movie knowing Saul Goodman is their dad. I kept cracking jokes to myself everytime I saw him thinking he would say “I might think of going to law school” making myself funny.

I think that this movie is proof that Bob Odenkirk immediately makes any movie better with his presence, even though it was already amazing before.

I think Beth’s death in this movie was more sad than in the book. At least in the book you knew that Beth had accepted her death was inevitable, and she was okay with being sent back to her god. The grief here is a lot stronger, though perhaps that’s more so because you can actually physically see it.

In this latest movie Beth also accepts that her death is inevitable though…

Beth was the only one who truly knew and appreciated what and why Jo did things the way she did and losing her was like losing her identity for Jo.

Greta’s version was the best. I loved this shifting in time lines… it was more exciting, and showed a better difference between childhood and adulthood

The parallels between past and present are so well done in this movie.

What an incredible film!

I never really appreciated the timeline up until this point. As a girl who was raised on Little Women- this story and these characters were family to me so when I sat down to watch it and it started in New York, I was just disappointed. I thought it could never be as special as the previous adaptations, let alone the book. And From Greta Gerwig and Saoirse Ronan? Honestly I was just heart-broken. But I grew to like it, appreciate a different view of the story.

But then christmas scene came. Honestly from there, I was a wreck. I cried throughout the rest of the movie. How seamlessly these two juxtaposing scenes conflict and contrast with each other whilst softly reminding you of what was or what could’ve been was honestly one of the most breathtaking and masterful pieces of storytelling I’ve ever seen. I cannot describe just how special this film was to me but I can say that it will go down in history as a revolution in both cinema and to little girls who will fall in love with this story for years to come, just like I did. 🙂

It was such a refreshing idea to cut the movie into two timelines. It made it not just a copy of the ones that came before. Just wish the editing was better.

I first watched Little Women at 26 without having read the book beforehand, though I already knew of Beth’s death due to a particular episode of Friends. Now I’m 27 and reading the book for the first time, and considering how much I love Beth I cannot imagine how I would react if I hadn’t known beforehand.

Best article on Beth ever.

I hope if there’s a remake of Little Women in the future, Beth will never die and she will be happy just like her sisters with her boyfriend or husband as well. 🙏

The movie literally broke me. Beth was probably my favourite character, such an amazing movie! Definitely my favourite movie I’ve seen in a long time.

When I was young this book was sad enough. Watching the film as a parent myself now, her death absolutely broke me.

Beth – the huge inspiration and purest heart out fi the whole family. My favourite character.

Does anyone remember Joey crying over Beth’s death or is it just me?

My school is performing this, and I play Mr. Lawrence, the interactions between Beth and Mr. Lawrence are phenomenal but completely tears me down when she passes.

My school also did this. I played Jo.

The 1994 movie was far from perfect, but i can’t help but appreciate Beth’s final scene so much more after seeing the TRAIN WRECK that was beth’s death scene in the newest movie.

This is the only scene in movie history that makes me cry.

This scene is killing me inside. A little more than 90210 when Ivy learns Raj cancer didnt go away and he is in the hospital on his death bed.

I’m thrilled to see Beth getting so much love. That was my goal with this article, and the comments tell me I did my job, so that’s great. Also, yes. I will die on the hill that Beth deserved, and deserves, better, especially from remakes and reboots. (Yes, I know. Don’t think I haven’t considered tackling this myself)! 😉

Ever since I watched the 2019 movie I always cry about Beth’s death.

I wanted to watch the 1994 version but I’m not going to go through the heartache of watching Beth die again. The 2019 was enough. 😔

As someone who revised this, I can say that I truly appreciate all the detail and depth you give every section of this article. It definitely made me see Beth March in many different ways, and had me considering the character in ways that I had not thought about before. Excellent work, and thank you for the piece!