Boris Karloff: The Heart of a Monster

In 1931 Universal Pictures released one of its definite horror films, Frankenstein, starring Boris Karloff. Born William Henry Pratt in a London suburb, Karloff did not come to Hollywood to do niche films. Still, he didn’t seem to mind his place as a horror icon. His role as Frankenstein’s monster transformed him from an average character actor into a star. Karloff’s characters, whether it is a science experiment gone wrong or a malevolent mummy, are based on the idea that “hearts of gold” beat beneath ugly or monstrous exteriors. This idea paired with Karloff ‘s physical presence and emotional resonance grounded his characters in our reality. A closer look at Karloff’s physical and emotional presence in films such as Frankenstein and The Mummy (1932) can explain his long-lasting and well deserved fame.

After the success of Dracula (1931), Universal quickly began work on its next big horror picture. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein seemed like a natural choice. Originally, Universal wanted fellow horror star Bela Lugosi for the role of the monster. Lugosi was not particularly interested in the role, mainly due to the lack of lines. Lugosi was able to decline on the condition that he would “furnish” an actor for the part. Cue William Pratt who had since employed a stage name, Boris Karloff. Karloff met with the makeup artist Jack Pierce and was offered the part shortly after. In 1967 Karloff said, “I had no idea the importance of the role, but Jack Pierce did: he stalled the test two weeks while working on makeup, and the makeup sold the part.” While the makeup would solidify the image of the monster in public consciousness, it is Karloff’s performance underneath that makes it remarkable.

Frankenstein tells the story of a mentally unhinged doctor who wants to create life. Paired with his assistant Igor, Dr. Frankenstein takes tissue from the dead to create a new human being. The doctor is successful, but shortly after he regrets that success, as he thinks the creature is flawed and ugly. Dr. Frankenstein did not understand that the child-like innocence of his creation makes him confused within his new surroundings. The monster does not know his own strength. He doesn’t understand right from wrong. Thanks to Karloff, the monster is a sympathetic creature and not a bloodthirsty monster.

As stated earlier, Karloff did not have any lines, at least not in this performance. Everything was pantomimed. In order for audiences to feel sympathy for a monster with no lines Karloff had to rely on his facial expressions and movements.

In Karloff’s first appearance in the film, the monster is under a sheet surrounded by Dr. Frankenstein and his hunchbacked assistant. Karloff’s movements are slow at first. He sits up, straightens his body, and looks to the light out the window. Much like a newborn baby, the monster freaks out at that which he doesn’t understand. When the monster can’t get to the light, his face clearly shows his frustration. He holds out his hands, pleading. In this scene, Karloff is positing the idea that the monster is baby, a baby in a body much too big and powerful for him.

The image of a small baby in a big body is illustrated again in a later scene. When the monster escapes his abusive father, Dr. Frankenstein, he meets a young girl throwing flowers in the lake. The blonde little girl is friendly, the picture of innocence, and not at all terrified by the lumbering monster approaching her. Soon the monster and the child are playing a game, tossing flowers into the lake. It’s a small thing, but the enjoyment is clear on his face. He smiles, sort of, and squeals in excitement. The little girl smiles as she allows the monster to play. But when the flowers run out the monster is confused. He looks to the little girl and thinks. “Oh, I can toss you!” Slowly, he reaches for her. For the first time in their meeting she is terrified. She screams as he pushes her into the water. The monster thinks this is all in good fun, he doesn’t think he’s doing anything wrong. until she stops moving. The monster panics, “What does this mean?!” In fright and confusion he runs off completely lost in an unkind world.

The success of Frankenstein gave the go ahead for several sequels. Karloff reprised the role as the monster in The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and the Son of Frankenstein (1939). Karloff got speaking lines in the Bride of Frankenstein. This was a very different monster than the monster in the first film. While not as memorable at his first go around, his performance still holds up today. It’s all thanks to the humanity and pathos he imbued in the first film, that he was able to take the character to new heights. Karloff continued to bring compassion to monsters in The Mummy (1932).

The Mummy tells the story of an ancient Egyptian priest, Imhotep (Karloff,) who is revived when an archaeological expedition finds Imhotep’s mummy. Imhotep was mummified alive for attempting to resurrect his forbidden love, a princess. The expedition is led by Sir Joseph Whemple, portrayed by Arthur Byron, and it’s Whemple’s assistant that wakes up Imhotep from his long slumber by reading an ancient life-giving scroll out loud. Once awakened, Imhotep searches for the modern reincarnation of the princess whom he loved. The villain of the piece, Karloff brings his own unique take on the historical figure.

Imhotep seems to be based on the same Romantic image as Bela Lugosi’s Count Dracula. Imhotep and Count Dracula have a hypnotic appeal to them that captivates women of all creeds. Karloff plays Imhotep as a tortured soul with a dark past. Through Karloff’s expressions and voice he gives the impression of being noble and having suffered much loss. Unlike Frankenstein’s monster, Imhotep is almost immobile, but the lack of movement attributes to his fragility and age. The clumsiness and childish air Karloff had brought to Frankenstein’s monster are replaced with grace and maturity. Another thing that sets Imhotep apart from the monster is his voice. Karloff had a low growling voice. Author Paul M. Jensen describes his voice as filled with “meaningful pauses, accented syllables, and the hollow cultured tone of time and infinite sorrow.” It’s these acting choices that carry Imhotep’s humanity. As the monster of the piece, Imhotep does many frightening things. He kills innocent people and unlike Frankenstein’s monster, Imhotep does this on purpose. He will take down anyone who will prevent him from finding his true love.

Despite his murderous ways, we as an audience are wary of him but we are not without sympathy. In one scene, the modern incarnation of his princess pleads for her life. Imhotep wants to reunite his princess’s soul with a new body. But this would mean the incarnation’s death. She pleads for her life. Imhotep, although mostly immobile, expresses a lot with his rigid movement. He always looks his princess in the eyes and he looms over her protectively. He says, “All I ask is for a moment of agony, only so we can be reunited.” Because he has loved so much and so deeply we can’t completely fault him for his behavior.

In another scene, when the reincarnated princess recalls her past life, she begs for forgiveness from the gods. Imhotep looms behind with a knife in hand. As he approaches her, his power begins to fade. The gods are protecting the princess. As this is happening, you can see Karloff’s face crumple. You see that he knows he’s going to die again. In his last shot, you see him slowly close his eyes and wait. He is resigning himself to die and that is incredibly sad. Although he went about things in a terrible way, he did so out of love and compassion.

Through characters like Frankenstein’s monster and Imhotep we are shown a despicable monster. But with a steady and more careful glance you will realize there is more to these characters. Karloff takes the monsters of our nightmares and gives them hopes, dreams, and a reality. They feel like real people, because they are. And we as an audience respect that and admire that. Karloff is not a horrific monster but a monster with a “heart of gold.”

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Cagney, this was a terrific analysis. I’ve yet to watch any of the classic Universal horror films (I think I may have watched Dracula and The Invisible Man), but you bring to light a lot of interesting points concerning Karloff’s portrayal of these monsters. Though they are grotesque and at times malevolent, there is a purpose that resides within them; a goal that they want to attain so that they may add meaning to their lives. That’s really great stuff. It makes me lament, to some degree, the current state of the horror film. Most modern films either have a human psychopath or a supernatural entity as the villain, but the one thing they have in common is that they are completely without sympathy. We don’t really care about Freddy, Jason, or whatever Demon is possessing someone because they are the incarnation of pure evil. And while that may be fun in a campy sort of way, it also hampers the movies ability to create pathos for the villain. It seems as though this is something that the classic films got right; by giving us a character with thoughts and feelings, they feel more real. Again, this was a fun article. I’ll be sure to check out Frankenstein and The Mummy some time.

Thank you for kind words! I agree most modern horror films don’t bother with creating a sympathetic monster. I guess to modern audiences pure evil is scarier than a more human evil. I hope you enjoy the Mummy and Frankenstein!

He gave a lot of good performances, but here I would like to acknowledge his cameo appearance in the 1947 film noir “Lured”. It’s one of my favorite cameos ever!

Karloff was typecast as a horror film actor and, indeed, those were his bread and butter roles for the most part. The fact remains, however, that he was one of the finest actors who ever lived. He could play a homicidal body snatcher in one film and a grandfatherly scientist in another. A cold blooded satanist in The Black Cat and Captain Hook in Peter Pan.

You have to be one of the best to be able to be versatile.

Great tribute. He deserved recognition as much as any other worthy actor.

He and Lon Chaney were supreme at their craft.

He never regretted being typecast in any of his roles. Something that many actors are afraid.

Hell of an actor. Hell of a gentleman. I’ve seen all of his movies.

Heck of an actor, heck of an analysis! Thanks for sharing!

Thank you!!

We now have a body of actors who are used to working under heavy prosthetics, make up, and “suits”, but Karlof, Lugosi, and Chaney were very much forging a new artform with their acting work in that era. The acting in silent films was often broadly telegraphed and unsubtle, so it’s really remarkable that Karlof and the others were able to bring such nuance to their work. I agree with the other commentors — we could use that level of delicacy in more fx work today.

greatest horror actor in the history of movies. did it without all the special effects of today.there’s never been another one like him.

Fantastic article, you clearly have a deep insight into Karloff’s acting abilities.

Thanks for writing about Boris Karloff – he is one of my all time favorite movie monster actors. I also though he did a great job as the voice and narrator of How The Grinch Stole Christmas.

It is true, as you say, that Karloff got speaking lines in the Bride of Frankenstein. But he didn’t want them. He felt that the creation should not be able to speak. The director thought differently, so he had lines.

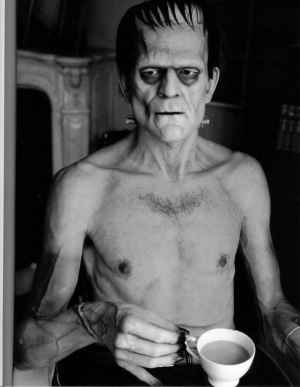

Lovely piece, however there is a major if understandable error in the illustration. That Monster drinking tea is not Boris Karloff, nor did it– not even “him” — even exist in 1931. This is a full-sized original sculpture by the brilliant Mike Hill done about 5 years ago.

Karloff’s cosmetics in Frankenstein look surprisingly advanced for 1931. This seems to illustrate that cosmetic designs for live action movies have not fundamentally changed in eighty years.