Coming Eye to Eye with the Beasts of the Medieval Imagination

The unicorn has traditionally been characterised as an elusive creature. It hides in dense forests, and legend has it that only a pure young maiden has the ability to capture it. So it is ironic that the unicorn has, in fact, a more ubiquitous existence in both popular and so-called ‘high’ culture than almost any other mythological creature. From medieval manuscripts and heraldic coat of arms to blockbuster movies and childhood literary favourites, the unicorn crops up everywhere. In fact, the unicorn has such a prominent place in western culture that many children will become aware of the unicorn before other real animals like the lynx or the platypus. Of course, it doesn’t help that most alphabet charts depend on a picture of a unicorn to teach the letter ‘U’, purely because of the sheer lack of nouns beginning with this letter in the English language. But still, it is strange to think that a wholly imaginary creature plays a central part in people’s lives from such an early stage in life.

And the fascination with the unicorn doesn’t end once children become adults, either. That is, not if you have any interest in the arts. The unicorn was a favourite during the Middle Ages, when it was used as an allegorical analogy of Christ – with its virgin captor signifying the Virgin Mary. The legacy of this medieval obsession is that unicorns can be found in museums all over the world, and they regularly make an appearance in all kinds of exhibitions, not just those focusing on the Middle Ages. This is made quite clear by three exhibitions that are currently underway.

The first of these exhibitions is taking place in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, UK. Bearing the alluring title Magical Books – From the Middle Ages to Middle-Earth, it presents delightful drawings by some of the best-loved fantasy writers – for example, C. S. Lewis (1898-1963) and J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) – alongside medieval manuscripts depicting strange mythological creatures. And surprise, surprise, one of these is the unicorn.

But this display of unicorn-mania in Oxford is nothing compared to what is currently taking place on the other side of the Atlantic. New York is experiencing a full-blown unicorn epidemic: The Cloisters, a branch of the Metropolitan Museum, is currently hosting an exhibition featuring not one, but forty unicorns. Appropriately called Search for the Unicorn, this exhibition celebrates the most popular work of art in the Cloisters collection, The Unicorn Tapestries. Dating from the late Middle Ages, this exquisite series of seven tapestries depicts the hunting and eventual slaughter of a hapless unicorn by a party of smug-faced aristocrats. The final scene is too tragic to describe, and it is probably not advisable to take sensitive children under the age of eleven to this exhibition – they might end up weeping for a week.

But this display of unicorn-mania in Oxford is nothing compared to what is currently taking place on the other side of the Atlantic. New York is experiencing a full-blown unicorn epidemic: The Cloisters, a branch of the Metropolitan Museum, is currently hosting an exhibition featuring not one, but forty unicorns. Appropriately called Search for the Unicorn, this exhibition celebrates the most popular work of art in the Cloisters collection, The Unicorn Tapestries. Dating from the late Middle Ages, this exquisite series of seven tapestries depicts the hunting and eventual slaughter of a hapless unicorn by a party of smug-faced aristocrats. The final scene is too tragic to describe, and it is probably not advisable to take sensitive children under the age of eleven to this exhibition – they might end up weeping for a week.

The unicorn has even made a presence at this year’s Venice Biennale. Taking over the entire city of Venice in Italy every other summer, this mammoth exhibition has served as a platform for up-and-coming contemporary artists from all over the world since 1895. Artworks typically have to be big, bold and brash in order to stand out and catch the attention of exhausted art-lovers, who will already have seen over sixty artworks that day. But this year, one clever Chinese artist realised that he could use a different strategy: exploit the power of unicorn to serve as a human magnet. Qiu Zhijie’s installation, The Unicorn and the Dragon features a translucent unicorn sprawled out in the centre of an empty exhibition space. Setting aside the question of what this installation is actually trying to say, there is no denying that Qiu’s strategy is an effective one. Unicorns simply demand to be looked at (again, how ironic).

Clearly, the unicorn continues to tingle the human imagination, regardless of age, and it is unlikely that its enduring appeal will come to an end any time soon. But lets face it: the unicorn is the Justin Bieber of the mystical animal kingdom. It has a huge following of devoted ‘beliebers’, and it has not budged from its centre-stage position for centuries. There is essentially nothing wrong with this, of course, but it has had the unfortunate consequence of drawing attention away from an array of other mythological creatures that also deserve our attention. They can all be found alongside the unicorn and boring animals like the pig and the chicken in medieval bestiaries, the richly illustrated encyclopaedias that claimed to represent all the animals roaming the earth … and elsewhere. These creatures range from the good, the bad and the ludicrously ugly (beware of the bonnacon). They are all fascinating in their own way, but three stand out more than the rest. The reason for this is because they each illuminate a thread of history that not only helps to explain why mythological beasts were so popular in medieval Europe, but also reveals that they still have a profound relevance in today’s world. This is the history of visuality.

The caladrius is the first member of this bestial trio. Described in antique and medieval sources as a large bird with piercing eyes that lives in the houses of kings, it was said that the caladrius had the ability to diagnose fatal illnesses and draw out non-fatal illnesses by staring into the eyes of the invalid. What makes the caladrius so interesting, is the fact that it healed with its eyes. The caladrius literally stared down the disease inflicting the invalid with its penetrating gaze.

Ever since the publication of Newton’s classic 1704 account of optics, which demonstrated for the first time that sight depends on the diffraction of light through lens of the eye, we have come to understand vision in passive and even mechanical terms: our eyes are nothing more than two slippery marbles that have been wired up to the brain. But the average medieval European understood vision in very different terms. During this period, the popular understanding of sight was that the eye sends forth beams, which physically ‘grope’ their way around the tangible world. The act of seeing was considered not passive but active – and very powerful. So giving someone the evil eye was considered a serious assault, which could have life-threatening consequences for the victim. Greek writers took this concept of the evil eye and created the hideous monster Medusa, a gorgon whose gaze was said to petrify onlookers to stone. Following suit, medieval writers created the basilisk, a giant snake, which also had the power of petrification. And if the gaze could harm, than it also had the power to heal, which is where the caladrius comes in.

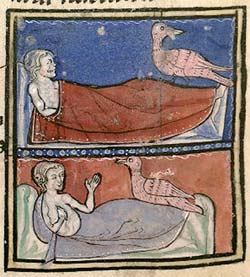

Its reputation as a miraculous healer meant that just like the unicorn – also believed to have miraculous healing powers – the caladrius was likened to the figure of Christ – who was, of course, regarded as the healer par excellence by the Christians of medieval Europe. Crucially, he was believed to have come to earth not simply to heal those suffering from physical diseases like leprosy and lameness, but more importantly, to cure the moral blindness afflicting the entire human race. This reveals that the popularity of the caladrius during the Middle Ages was not symptomatic of a deluded desire for a bird-shaped elixir of life, but an obsessive anxiety regarding the fate of the human soul after death. To turn a blind eye to the sins of humanity – especially your own – could mean that the redemptive gaze of the Almighty also turned away from you, thus condemning your soul to eternal damnation. Bearing this in mind, we can fully appreciate what pictures of the caladrius must have meant for medieval Christians; and we can share the sense of relief expressed by pictures like the one provided here, in which a man anxiously waits to see whether the caladrius will turn its piercing gaze upon him. It does, and the look of exultation on the man’s face is a pleasure to behold.

Its reputation as a miraculous healer meant that just like the unicorn – also believed to have miraculous healing powers – the caladrius was likened to the figure of Christ – who was, of course, regarded as the healer par excellence by the Christians of medieval Europe. Crucially, he was believed to have come to earth not simply to heal those suffering from physical diseases like leprosy and lameness, but more importantly, to cure the moral blindness afflicting the entire human race. This reveals that the popularity of the caladrius during the Middle Ages was not symptomatic of a deluded desire for a bird-shaped elixir of life, but an obsessive anxiety regarding the fate of the human soul after death. To turn a blind eye to the sins of humanity – especially your own – could mean that the redemptive gaze of the Almighty also turned away from you, thus condemning your soul to eternal damnation. Bearing this in mind, we can fully appreciate what pictures of the caladrius must have meant for medieval Christians; and we can share the sense of relief expressed by pictures like the one provided here, in which a man anxiously waits to see whether the caladrius will turn its piercing gaze upon him. It does, and the look of exultation on the man’s face is a pleasure to behold.

The example of the caladrius makes very clear that the act of seeing was understood as more or less synonymous with power. It could do much more than simply provide the human mind with a window onto the world. And since power always breeds fear and insecurity, it comes as no surprise that another mythological creature became as familiar as the caladrius during the Middle Ages, which was born of an intense fear of being seen. The parandrus is described in various accounts from antiquity and the Middle Ages as a hybrid creature with the body of a bear and the head of a stag, which took on the appearance of its surroundings – rather like a chameleon. Its hide was prized for the obvious reason that it could be used to make the wearer invisible, and it was this power of the parandrus to avoid being seen that made it so compelling for medieval Europeans. In this sense, it is similar to the unicorn, which was also considered powerful precisely because of its ability to elude unwanted attention.

Across the fantasy and science fiction genre, the desire for invisibility invariably expresses fear and insecurity, from the vain emperor in The Emperor’s New Clothes (1837) by Hans Christian Anderson (1805-1875), to the painfully self-conscious Dufflepuds in C. S. Lewis’ third book in the Narnia series, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952). No doubt, it was the sense of being watched by the all-pervasive gaze of God that instilled the deepest insecurity, but there were other more ‘worldly’ eyes that also fed this desire for invisibility: it doesn’t take a great stretch of the imagination to substitute poison-eyed demons like the gorgon and the basilisk with human beings – we ,too, are capable of looking poisonously (stalkers, for instance). S0 it is likely that these beasts were used to symbolise enemies from neighbouring villages, countries and beyond. To avoid being seen by those with malicious intentions meant survival – so an invisibility cloak made from the hide of a parandrus certainly would have been useful when unexpectedly coming face to face – or rather, eye to eye – with one’s adversary.

Last but not least is the manticore. A hybrid like the parandrus, the manticore was said to have a lion’s body the colour of blood, the face of a glaring man and the venomous tail of a scorpion. A resident of the Indian continent, it reportedly fed on human flesh. So what compelled the invention of such a hideous beast? One possible answer becomes apparent if we compare the manticore to the aliens of early science fiction literature. It is no coincidence that the genre of science fiction really took off once space travel became a genuine possibility and ambition during the mid-twentieth century. Suddenly made aware of a vast universe full of billions of planets, people inevitably began to speculate about the possibility of some planets being inhabited by malicious aliens. The medieval worldview was much more limited, and for most people living in Europe during the Middle Ages, India was the equivalent of a distant planet. It lay beyond the familiar boundaries of Europe, so for all they knew, it could be home to manticores and other even more fearsome beasts – like foreigners, for instance. In fact, drag postcolonial theory into this discussion and it becomes possible to regard this European projection of mysterious and malicious beasts onto the landscape of non-European territory as symptomatic of feelings of ambivalence toward the social/cultural Other.

Last but not least is the manticore. A hybrid like the parandrus, the manticore was said to have a lion’s body the colour of blood, the face of a glaring man and the venomous tail of a scorpion. A resident of the Indian continent, it reportedly fed on human flesh. So what compelled the invention of such a hideous beast? One possible answer becomes apparent if we compare the manticore to the aliens of early science fiction literature. It is no coincidence that the genre of science fiction really took off once space travel became a genuine possibility and ambition during the mid-twentieth century. Suddenly made aware of a vast universe full of billions of planets, people inevitably began to speculate about the possibility of some planets being inhabited by malicious aliens. The medieval worldview was much more limited, and for most people living in Europe during the Middle Ages, India was the equivalent of a distant planet. It lay beyond the familiar boundaries of Europe, so for all they knew, it could be home to manticores and other even more fearsome beasts – like foreigners, for instance. In fact, drag postcolonial theory into this discussion and it becomes possible to regard this European projection of mysterious and malicious beasts onto the landscape of non-European territory as symptomatic of feelings of ambivalence toward the social/cultural Other.

The manticore, it seems, is but one example of the monsters and aliens we humans fill the blindspots of our world with – because seeing something that we ourselves created is less unsettling than staring into inexplicable nothingness that we have no control over. Just as their fear of the dark compels children to imagine that nightmarish monsters are lurking in the shadowy depths of their closets or beneath their beds, and just as science fiction writers populate the uncharted universe with more and more hideously demonic aliens, medieval Europeans filled the uncharted world beyond the frontiers of Europe with strange beasts. The manticore is the product of a state of blindness, perhaps there is no greater catalyst of the human imagination than being deprived the the ability to see reality as it appears to the naked eye. Indeed, some of the most innovative and imaginative people in history were blind: John Milton (1608-1674), Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) and the Hindu poet and saint Surdas (15th century), to mention but a few.

Whether they represent the supernatural potency of the gaze, the fear of being seen, or the fear of blindness, the caladrius, palandrus and the manticore all provide us with a fascinating glimpse into the medieval world. But they can help us to understand more about the nature and experience of visuality in our own age, too. After all, the medieval understanding of vision appears to have endured in spite of what science has had to say on the matter: we still commonly use the expression ‘to give someone the evil eye’; many psychologists recommend carrying out visualisation practices, with the promise that they will physically rewire your brain and help you to revolutionise your life; and pick up a recently published medical encyclopaedia, and you will find an entry for scopophobia, a condition whereby someone suffers from a morbid fear of being stared at … which sounds remarkably like the elusive unicorn and the invisible palandrus. Then there are, of course, the myriad mechanical eyes that have been watching us with intensifying degrees of scrutiny since the birth of camera more than two centuries ago. The list goes on, but they all reinforce the medieval conviction that there is nothing remotely passive about visuality.

What began as a childish search for the lost cousins of the medieval unicorn has ended up raising some rather serious and grown-up questions. This is because visuality is inextricably bound up with morality and ethics. And as bestial embodiments of visuality, all of the creatures examined in this article invite us to ask ourselves moral and ethical questions that are both timeless and timely: Are we being watched by a higher being, and does their gaze have the power to heal us of our blindness, just as the caladrius promised? Can we turn a blind eye to troubling situations that don’t immediately concern us, or is it our moral responsibility to bear witness to all that we see? Can we ignore the atrocities taking place in far-off places because we have only seen them through the indifferent eyes of the media? Will society be safer if we allow Big Brother to survey us from every street corner? Is the internet turning us all into voyeurs and exhibitionists? Are there certain kinds of images that we ought not to look at for moral and ethical reasons?

To see, or not to see? That is indeed the question. It has no simple or straightforward answer, but it has hopefully become clear that the weird and wonderful beasts of the medieval imagination can help to illuminate our understanding of visuality and open our eyes to the blindspots of our own lives.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Would I love to attend the Search for the Unicorn exhibition! Sounds well appealing!

I wrote about this in my blog the other day. A girlfriend once shared the sweetest story with me. It was about a unicorn. This moment she shared happened during her years of living in the city of New Orleans. Though I have never been myself, (my only frame of reference being the black and white movie, A Streetcar Named Desire, which I have seen many, many times), she prefaced herself by telling me that this story portrayed her city perfectly. She went on to recount a conversation her husband overheard while pushing their son on a swing in the local park. As a unicorned woman rode by on her bike, a father said to his own child, “Look! It’s a unicorn!”

The father did not call her a woman dressed as a unicorn. Neither did he comment on how strange she was to be dressed as a unicorn. Rather, this father shared a rare unicorn sighting with his child, while playing in the park.

It is never surprising to me to find a child with an imagination. It seems equally natural to also find the grown up standing behind said child, correcting their imaginative perceptions. This story makes me smile for so many reasons. It is also yet another reason why I must one day visit New Orleans.

Thank you so very much for the very well written article, it took me on a pleasant trip of nostalgia.

This is a really interesting article, written clearly and articulately. I’m interested in both fantasy and visual theory, but Medievalism isn’t an area I’ve really explored as of yet.

Thanks for this informed insight into some of the psychology behind these beasts!

Very fascinating article. Well-researched and articulate with strong intellectual and creative ideas. I would love to see an article on a combination of other mythical creatures.

Fantastic, informative article. I am now intrigued…

Very impressive article, a very creative and well researched piece and seemingly effortlessly well written; I love the dry humour bubbling under the surface. I’ll bet you’ve deliberately uploaded a picture of a Blue Tit because your name’s Finch…

Thanks for sharing your thoughts and stories – very much appreciated! @Ged, I suppose my profile pic doesn’t really make sense, lol. But yes, just as well I like birds.

A lovely article 🙂 very nice insights (there’s anther one!) and take on mythological creatures. I didn’t know of the palandrus so thank you for introducing me.

First article i’ve read here and it was truly fascinating! Very well researched and prompted a lot of my own investigation throughout! I especially enjoyed the wider links to religion and modernity.

Wow… Truly impressed by your article! I saw the banner picture of the unicorn and the first example picture of the unicorn tapestry and recognized them from the children’s animation The Last Unicorn and thought to myself, huh this otta be cute! I was very wrong- and not disappointed in the least!

Your introduction on the popularity and current role of the unicorn in the beginning was very interesting and I thought you did a great job sticking to historical items, not relying on films like The Last Unicorn or Harry Potter. This article seems to focus more on the unicorn’s three top mythical cousins rather than the unicorn itself, which I didn’t see coming, but was altogether amazing. The amount of detail and knowledge in the history and representation of these lesser known mythical beasts was nothing short of astonishing- I am truly blown away by how much you know and explained. Your analysis was just as mind blowing, and the way you tied everything back up in the end with real-life questions and implications was nothing short of awesome. I really enjoyed reading it, and feel like I’ve learned so much!!! Thanks you!

Fantastic job- to see or not to see? Love it!

Thank you for leaving such a lovely message – I’m glad this article is being read and enjoyed!

Best,

Sarah

Thanks for this great article. You’ve helped me look at unicorn symbolism in a new way. Like many, I always associated this aspect of medieval and Renaissance folklore as an aspect of purity and unalloyed idealism. The connections you make to ideas of invisibility and visuality are profound as they make us question the concept of seeing in medieval art. I liked the connection you made to Qiu Zhijie’s recent work as well as contemporary artists re-appropriate what the idea of the unicorn means to them: http://www.qiuzhijie.com/worksleibie/zhuangzhi/unicorn.htm

Glad you enjoyed it, and it sounds as though you really know your stuff – it’s amazing how certain ideas can be traced through such vast expanses of time thanks to the art that cultures left behind.

Thank you, Sarah. Though the thanks really goes to you for your insightful essay. It’s always fascinating when different threads in seemingly disparate periods of history, medieval and contemporary, can be brought together to think of a certain aspect of art or folklore in a new way.

I’m not surprised to learn that so many creatures with healing qualities were popular during the middle ages. I guess that many a plague victim thought of them.

What an interesting and well articulated article! I haven’t really had a chance to study Medieval art, so I am unfamiliar with the topic and iconography, but I have always fancied chimerical creatures. Fascinating read!

Such an insightful article. I’ve never thought about these creatures in such a way. You did a great job and have a beautiful writing style. Thank you for such a great article!

I agree with many of the comments above. This is a fascinating subject with a lot of possibilities. Perhaps a series of articles on the evolution of such medieval folkloric creatures and the ways in which they’ve been adapted or refashioned in contemporary culture. It’s interesting because I can’t think of occasion in which the unicorn is portrayed as anything except love and purity with magical, fertility, or healing powers (hence those ties to Christianity or nobility). Still, there is a wildness and certain dangerous aspect tied to this purity. I can’t help thinking of Ridley Scott’s famous use of the unicorn in Blade Runner (and later Legend). Thanks for the article! I hope to read more.

Loved this article – and not just because you use an image from one of my favourite childhood films, ‘The Last Unicorn’ as your header! I think medieval bestiaries are begging to be explored by authors/film-makers etc. and your article proves this point.

Interesting article but I would argue that the dragon has appeared about as many times as the Unicorn at times, it too is very prevalent.

Wow. I know this post is now a year old but I’ve only discovered it today and I found it fascinating! Great writing style, interesting arguments and a fascinating in-depth-look at medieval myths that you relate to our contemporary fears in a very adequate way. Really, well done!

Lovely article on medieval myths. I remember learning about these fantastic creatures from the JK Rowling side stories.

This was an interesting article on an unusual topic that goes down various unexpected paths. I kept thinking I wonder what the author is going to say next.

I feel that this text was written from the heart, but perhaps a little too much so. Your use of modern comparisons like “Justin Bieber” feel a little divorced from your text and subject. You often use an informal tone, which can be refreshing if used sparingly. In this case, it puts a lot of emotion in your text and I think it weakens your arguments and point. I liked your topic.

Thanks for this article! I find it great to broaden people’s knowledge, especially when, as you rightly point out, unicorns get so much attention!

It reminds me of JK Rowling’s “Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them,” a much less scholarly undertaking that your approach, for sure.

I like your approach as well, to consider the greater role of perception in how these creatures are conceived and understood. Just thinking of how ‘rare and hard to find’ unicorns are, and how prominent they are in people’s mindsets, makes me think of how much our ‘collective consciousness’ is interested in that which it cannot access.

Thanks for the great work!