Dante and Swamp Thing’s Journey Through “Inferno”

I took a class last semester during which we read the entirety of Dante’s Divine Comedy. It was the first time I’d read the Comedy as a whole and also the first time I was allowed to write about comics in an academic setting. I had intended to write about the second annual issue “Down Amongst the Dead Men,” in which Swamp Thing descends into a Dantean hell to rescue his lover, Abby Arcane. But as I reread the series, I noticed that all of Alan Moore’s run on the series essentially mirrored Dante’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. Not only that, but the themes contained in each work, specifically the aversion to earthly authority, were nearly identical. Alan Moore, kind soul that he is, would probably take issue with anyone saying his work was anything other than wholly original, but the similarities are too vast to ignore. Books 1 & 2 in particular mirror Dante’s Inferno.

Inferno is the first and most well-known book of Dante Alighieri’s three part epic poem “The Divine Comedy.” It details Dante’s journey through the nine circles of Hell guided by his hero, the poet Virgil. The poem begins with Dante meditating on his life in a dark wood, when he comes upon three wild beasts; a lion, a leopard, and a wolf. What these animals actually represent has been the subject of much academic debate but the important thing is that these animals are blocking Dante’s direct path to salvation. Beatrice, an unrequited love of Dante’s, sends Virgil to help Dante find his way. Virgil then guides Dante through the nine circles of Hell, where the sinners are each punished according to their sins. Those guilty of Wrath, for example, must eternally battle one another while those who have committed suicide are turned into trees that forever tormented by birds. One major theme of the Inferno is the “weight of love,” it is our desires for love, money, or power that send us to Hell rather than God. When we first cross the river Acheron into Hell we see souls jumping over themselves to get in, they loved their sin more than God and so they’re anxious to continue to that sin. Another is that sin is inherently human, and that is one explanation for why Fraud is punished more severely than sins of Lust or Gluttony. The more animalistic our urges the less we can be blamed for them. It is the political crimes, such as the betrayal of Caesar by Brutus or the corruption of Archbishop Ruggieri, that receive the worst punishments. In addition to being a brutal political commentary, Dante’s journey through Hell is one of awakening, one in which he is forced to face the reality of sin. Before he can ascend to Heaven, he must literally go through Hell.

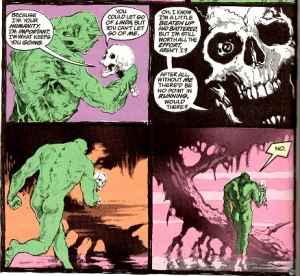

Swamp Thing was created in 1971 by Len Wein. In 1984 Alan Moore breathed new life into the character, saving the comic from cancellation. During that time, he radically changed both the story and overall tone of the comic. No longer simply a man who had been deformed by an explosion in the swamp, Swamp Thing became a being of pure plant who only thought he was a man. The breakthrough issue “The Anatomy Lesson” is Moore’s second issue in the series, the first one necessarily tying up loose ends from a previous story arc. In “The Anatomy Lesson” we learn that despite Swamp Thing’s desire to regain his human form, there is no longer any human left. As Dr. Woodrue, the doctor charged to perform Swamp Thing’s autopsy says “We thought that the Swamp Thing was Alec Holland, somehow transformed into a plant. It wasn’t. It was a plant that thought it was Alec Holland! A plant that was trying its level best to be Alec Holland…” The question of the entire series then becomes how to lead a meaningful life when denied humanity. Swamp Thing mourns the loss of his humanity, he retreats into The Green and actually carries around the bones of Alec Holland. In a scene reminiscent of Hamlet’s “Alas, poor Yorick” speech, Alec’s skull tells Swamp Thing “I’m your humanity. I’m important. I’m what keeps you going.”

Later, he gives himself closure by giving Alec Holland a proper burial. Swamp Thing then becomes a paradox, he lays aside his humanity and embraces his plant-self, but also maintains a constant desire for humanity. He appears in a human-like form, with a head and arms and legs, he loves a human woman, and he involves himself in human problems. Essentially, he rejects the bad parts of humanity; the cities, the greed, the wrath; for the best parts of humanity. Swamp Thing’s identity is a theme explored throughout the narrative, and whether he is a man or a monster is the subject of much debate within the story. This beginning mirrors Dante’s own beginning “within a dark wood.” Just as the dark wood is a symbol for the moral corruption in Dante’s life, Alec Holland represents the dark side of humanity within Swamp Thing. Although, like Dante, Holland was not a bad person, he was still corrupted by the earthly pleasures of the world.

It is his love for Abby Cable who keeps Swamp Thing tethered to his humanity just as Beatrice is the inspiration for Dante’s own spiritual journey. When Swamp Thing first discovers that he is no longer human he retreats into The Green and withdraws completely from humanity. He resigns himself to just being a plant, since he is neither human nor monster. In the same way that Beatrice tries to bring Dante back to God, it is Abby’s cries for help that bring Swamp Thing out of The Green and back to the world of man. Dr. Woodrue, a kind of plant/human  hybrid himself, is attempting to overtake the world of man with that of plants. Swamp Thing makes him see the importance of balance in the world and that plant life cannot weigh too heavily on the scales. Woodrue argues that “The plants will pour out oxygen, and all the animals will die. Only we shall remain. Don’t you see? It’s the only way to save the planet from those creatures” To which Swamp Thing responds “And what…will change the oxygen…back into…the gasses that…we need…to survive…when the men…and animals…are dead?” The importance of the balance between plant life and animal life is only one that Swamp Thing can see, as someone who walks in both worlds. This is a balance that Dante first learns about in Inferno, where sinner’s punishments must be equal to their crimes no matter their intentions. Woodrue, as his punishment, is ejected from The Green. A similar punishment to all those in Hell, whose main suffering is their distance from God.

hybrid himself, is attempting to overtake the world of man with that of plants. Swamp Thing makes him see the importance of balance in the world and that plant life cannot weigh too heavily on the scales. Woodrue argues that “The plants will pour out oxygen, and all the animals will die. Only we shall remain. Don’t you see? It’s the only way to save the planet from those creatures” To which Swamp Thing responds “And what…will change the oxygen…back into…the gasses that…we need…to survive…when the men…and animals…are dead?” The importance of the balance between plant life and animal life is only one that Swamp Thing can see, as someone who walks in both worlds. This is a balance that Dante first learns about in Inferno, where sinner’s punishments must be equal to their crimes no matter their intentions. Woodrue, as his punishment, is ejected from The Green. A similar punishment to all those in Hell, whose main suffering is their distance from God.

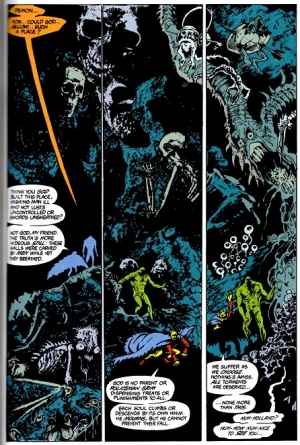

The Second Annual issue of Saga of the Swamp Thing is the most vividly Dantean issue in the series. In it, Swamp Thing must find Abby in the afterlife. He first goes to Heaven, where he meets the real Alec Holland, then is granted access to Hell by another DC Comics character, The Spectre. Like in The Divine Comedy, Swamp Thing needs a guide for each level of the afterlife he visits. When he first arrives in the realm the newly dead, it is the character Deadman. Shortly after, The Stranger guides him through heaven and to The Spectre. Before Swamp Thing enters hell, “the demon that fancies himself half a man” appears, Etrigan. Similar to Swamp Thing, it is Etrigan’s desire for humanity that enables him to appear on the side of good in many of his appearances. He agrees to guide Swamp Thing through hell in exchange for a flower on The Stranger’s lapel, “plucked upon the western slope of heaven.” Etrigan shares many traits with Dante’s guide through Inferno, Virgil, but he is a parody of the virtuous pagan. Etrigan is a demon, and although, like Virgil, he agrees to help Swamp Thing for a glimpse of heaven, he does so because seeing this flower from heaven will make hell seem even worse for the souls he tortures. Most glaringly, Etrigan is a rhyming demon and Virgil is a poet. However, Etrigan’s rhymes are uneven and childlike, closer resembling limericks more than epic poetry. Etrigan is also filled with knowledge of hell, like Virgil. When Swamp Thing asks, as Dante did, how God could allow such a place, Etrigan responds:

“Think you God built this place, wishing man ill and not lusts uncontrolled or swords unsheathed? Not God, my friend. The truth’s more hideous still: These halls were carved by men while yet they breathed. God is no parent or policeman grim dispensing treats or punishments to all. Each soul climbs or descends by his own whim. He mourns, but He cannot prevent their fall. We suffer as we choose. Nothing’s amiss. All torments are deserved.”

As in Dante, where the weight of love makes sinners appear eager to go to hell, man has here created his own hell. “We suffer as we choose” sums up Dante’s philosophy on free will and divine justice perfectly. Each soul has control over where he or she will spend eternity, even if they feel they had no other option. Evil is merely an absence or distance from God.

Moore’s conception of hell shares a great many other similarities with Dante’s. When Swamp Thing reaches Anton Arcane, the evil scientist who killed Abby, his punishment is to have insect eggs hatching eternally inside of him, rendering him a hideous blob of a man with bugs crawling out of his every orifice. It is a punishment suited to the crime, as a servant of The Rot, which uses insects to infest and infect. Like Dante’s sinners, he also seems to show no remorse for his crimes, instead taking pride that his plan to send Abby to hell worked. He is obsessed and devoured by his sin, as many of Dante’s sinners were. His mobility is also severely limited, like Dante’s sinners, by his punishment. Arcane is so large and bloated by the insects inside of him that movement is nearly impossible. He is also unaware of time and his place in it. He asks Swamp Thing “How many years have I buh-been here?” and is shocked when Swamp Thing tells him he only died yesterday.

Swamp Thing’s journey to the afterlife and hell serve as an ending to the first act of Alan Moore’s Saga of the Swamp Thing. Like Dante, Swamp Thing must descend in order to rise, first by becoming less than human, realizing he lost his humanity and was indeed never human to begin with, so that he may rise above humanity and become a hero. Moore also uses his first two volumes to set up important questions concerning the problem of evil. Using Woodrue and Arcane, Moore mimics Dante’s ideas of the perfection of God’s justice. Like in Inferno, punishments are suited to the crimes and intent does not matter. The first act ends with Swamp Thing’s visit to hell, a summary of the previous issues. Dante also chooses to end his volumes in similar ways, with symbol packed microcosms. Swamp Thing must descend into a place where humanity is at its worst in order to save the best part. Moore expresses his own Dantean beliefs in free will and divine justice through Etrigan, the demon parody of Virgil. Swamp Thing emerges from hell with Abby and if not the humanity of the man he thought he was, at least an aspiration to humanity.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I liked your article. It was well written and you made an interesting connection between two pieces of work that I wouldn’t have readily put in the same sentence.

I am glad I got into Swamp Thing. I picked up Alan Moore’s run a few months ago after hearing about it from somewhere and getting intrigued. My favourite comic book of all time, I think.

As I was reading Vol 1, I could not help but note of how much Gaiman’s Sandman (which was very important to me as a teenager — through college particularly) is pattered exactly after the first two years of Moore’s Swamp Thing, from the superhero appearances within the first eight issues through the descent into hell and return and even the early horror emphasis giving way to something else entirely.

Neil Gaiman has commented on how much Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing influenced his own writing and credits it with being the reason he got back into comics. Neil Gaiman even says that Alan Moore actually taught him to write comics scripts.

Well I’ve travelled a goodly distance since I last read the Divine Comedy, and what a long strange trip its been. It is more of a journey than a book.

Great article Natalie.

Very well written and an engaging topic. I’m curious to ask if Swamp Thing’s redesign sits well with you or not.

There isn’t much about the New 52 in general that sits well with me, to be honest. But the erasure of Alan Moore’s concept that Alec was a plant who thought he was human rather than a human transformed into a plant was especially distressing. I only read the first couple of issues before I dropped it.

Quite fascinating. I’m a huge fan of the Divine Comedy but I never would have thought to put it in dialogue with a comic book let alone Swamp Thing. Great job at making my brain make connections it hadn’t thought about before!

You should check out Gary Panter’s Jimbo comics if you’re a fan of Dante ; )

I need to quit busting around and order these hardbacks. But I keep hearing the paper quality is terrible.

Jeff- DC just published a new Alan Moore anthology of Swamp Thing where the paper is much better than their Showcase series of books. The paper is still not up to standards of the newer material, however it is not newsprint ads a lot of these big books are.

The paper quality isn’t exactly poor, but it’s not glossy like we’re used to seeing now. I personally feel that it contributes to the overall pulp-y feel that is so integral to Swamp Thing’s aesthetic. And it works with the colors beautifully.

The introductory pages of these are quite something – they built it up unlike any other comic I have read.

I have read Dante’s Inferno, but never the entire series, and I loved getting this view point. I think comparing it to a comic book made it click a little better in my head and makes the topic itself more accessible. Really interesting read.

You might want to try working on a more captivating opening, because the current one just appears to be you talking to somebody about what you read (which I know is what you’re doing, but there are ways of giving it more semblance of an article).

The thing is already published. What’s the use?

I knew that Swamp Thing had a connection with death, but I never realized that it went as far as to paralleling Dante. Very interesting article. Definitely looking more into the Swamp Thing series now.

Great article. Who knew comics and epic poetry could have so much in common! I have read Dante’s Inferno, and I’m not much of a comic book connoisseur, but I can appreciate this sort of comparison (as an English major from a liberal arts college? I guess that’s the reason). I’m curious about a few things though: 1) “The more animalistic our urges the less we can be blamed for them.” Could you flesh this out a bit more? By what (extensive) reasoning can this be true? I just don’t see why it would be an issue of blame, but maybe that’s also because I have a hard time seeing sin on such a relative scale. 2) “Evil is merely an absence or distance from God.” Again, I just want to hear a little more on this. It’s interesting that both narratives (Inferno and Swamp Thing) see evil less as an entity than a metaphysical state. This surprises me especially for the comic, where characters–heroes and villains–tend to be, essentially, the physical embodiment of a a concept or moral trait. At least, that’s what I know about comics. 3) Finally, the discussion on humanity here really interests me, especially with Swamp Thing’s apparent vacillation between embracing his humanity and rejecting it, and the artist/author’s own confusion about it. I wonder if you’ve watched or read about the anime series “Attack on Titan”? I wonder if there are parallels in that “comic” with Swamp Thing in this area.

1) The god/animal division is from a standard of medieval theology that Dante was familiar with and uses in his poem, it states that the soul is divided into 3 parts, god/animal/plant. The lower tier sins, such as lust and wrath, can also be found in the animal kingdom and are from the animal part of the soul, while the more “human” sins, such as fraud, are punished more severely because they are a willful perversion of God’s will and the God part of our soul. 2) The Medieval Christian God is all-knowing, all-present, and all-good and so in order for evil to exist, God would have had to create it, which an all-good God would not have, and also BE evil, which an all-present God couldn’t be. Therefore, evil must simply be an absence or distance from God rather than another outside force or entity that is distinctly not God, because that just can’t exist. Again, this isn’t really outside the box for medieval thinkers, but within the superhero genre of comics, at least, it is fairly interesting. Superheroes/villains tend to be archetypes and metaphors rather than fully fleshed out individuals and while that has changed recently, but Alan Moore’s work is largely more philosophical than one might expect, and I think he’s at his best in Swamp Thing. 3) No, I’ve not read Attack on Titan

Great analysis! Alan Moore-era Swamp Thing is by far my favorite comic series, and although I knew of the parallels with Divine Comedy, I didn’t know the extent of them. Interesting stuff.

Interesting study! I just love this comics!

I enjoyed ST more than WATCHMEN. I think Moore’s depiction of flawed, aloof heroes in this one foreshadows his exploration of that theme in WATCHMEN.