Navigate Into David Lynch’s Desirable And Nostalgic Centre

It took a long time for David Lynch to see that his works for cinema and television were much more aware and known than his paintings and other artworks to both the academic and the public. He began his art career as a painter and designer. Lynch stepped towards cinema on one night’s sudden imagination of an “all-black painting moving” at Pennsylvania Arts School and he then made the decision to enrol at American Film Institute a few years later where he started his voyage of making “painting in perpetual motion”.

In the cinema of David Lynch, it is a regular encounter for us viewers with those extremely stylised décor, repertoire, mise-en-scene and lighting which are not departures from the essence of the architecture and furniture he designed earlier in his art career as a painter, and they are all the very elements which make Lynch’s films instantly recognisable and distinguishable. Lynch is not the only director who comes to cinema from painting and “align process of cinematic construction with the plastic arts”, however he is the very one who makes original human life transient as itself plastic. As suggested by popular film critic strand, the interconnection between painting, movement and sound is integral to all of Lynch’s subsequent film work. Centred with Lynch’s visionary engagement with his paintings, when added sound, Lynchian cinematic world reincarnates the static nature of paintings and go beyond the frame. In this article, I will focus on the very idiosyncratic visual design as film painting and sound design to investigate the desirable and nostalgic centre of the Lynchian cinematic world.

Cinema has in common with painting what is referred to as “determination of technical materiality of its existence”, and what Lynch’s cinema shares with his painting is metaphysical abstraction. According to Andreas Platthaus, for religious and allegorical art, abstraction is employed as a technique in creating an artistic world beyond the “earthly representation of the reality” in order to share the “unfathomable universality”; while for twentieth-century artwork, the abstraction is “concrete” and “based on the rejection of representational subject matter” whereas achieving the same effect as religious and allegorical art do. Without even raising viewers’ doubt if something in certain artworks has been interpreted, this “concrete abstraction” engenders and offers countless possibilities in individual interpretation of certain works. This “concrete abstraction” is employed and achieved regularly throughout almost all Lynch’s film paintings, ranging from the early surrealist work such as Six Men Getting Sick (Six times) (1967) which is based on his own painting, to the latest feature Inland Empire (2006) which shows the very stylish painterly design. I would argue that Lynch’s painterly “concrete abstraction” achieves on one hand through the painterly images and on the other hand through the painterly experience, that is treating film as an unfinished painting and adding ideas and inspirations at any time of the creation process. Firstly, film painting reveals through painterly images.

In Greg Olson’s biographical study of David Lynch, he puts forward one of the reasons why Lynch’s cinematic images are more like painting than literary constructs: “canvases vibrant with an action-painter’s abstract strokes of moods and atmosphere”. One noticeable example of the painterly image of concrete abstraction is the “interior” design shown in Lynchian cinematic world, such as the nightclub owner Ben’s home in Blue Velvet (1986), the Red Room in Twin Peaks, the Commando Room in Mulholland Drive (2001), and the Rabbits’ Room No.47 in Inland Empire (2006). These stylised and strangely composited interior design and film frames are all set in very static and unnatural ways. Functioning as the mystery centre of Lynchian cinematic world it generates uncertainty and curiosity inviting viewers to search and investigate further. These unusual and static images and interior design “reject the regularly representational subject matter” and thus reveals proliferation of meaning for viewers via uncertainty and abstraction, so they are more like paintings rather than photographs.

On the other hand, the “concrete abstraction” of Lynch’s film painting lies in its painterly experience. Olson further remarks that Lynch treats film sets like an unfinished painting canvas that he would keep actively adding new ideas to it and develop it via “intuition and experimentation rather than detailed planning beforehand”. Keep editing and changing how the film goes is considered a great way to lead to concrete abstraction of Lynchian cinema.

Even in Lynch’s most “straightforward” film The Straight Story (1999) which was shot in chronological order and is his only film not written by Lynch himself, Lynch kept editing the screenplay all the time and changed the shooting ideas when his crew was shooting along the actual route of Alvin Straight, making this “straight story” not straight at all but with prolific meanings and interpretations from each conceivable Lynchian scene for individual viewers. For example, the film ends with Alvin looking up into the sky, and then the camera pans up to the wall against Alvin and very quickly fades away into the endless starry sky which ends the whole film. The starry sky over Iowa is a reference to infinity and limitlessness when it is moving consistently into further and this offers viewers a feeling of flying away from the earth into a limitless space, and we are invited into what Platthaus called the “abstract hinterland of David Lynch”.

A starry sky connoting infinity is not a novel representational subject matter, however, this beautiful and stylised ending does offer different interpretations of the film, as the consistently moving stars warps and deconstructs the continuing spatiality and temporality of this single shot and thus makes our gaze exceeds the frame. This ending allows spectators to rethink the meaning of family and friendship, as well as the meaning of life. Lynch called this film his “most experimental film”, and “the concrete abstraction” of the painterly experience is achieved through the always “adding” and “ongoing” process of making The Straight Story. Therefore, through the painterly image and painterly experience, we experience the “concrete abstraction” of Lynch’s film painting, and “concrete abstraction” is one aspect in which film is in common with painting.

In Lynchian cinematic world, music is an important element in making Lynchian film painting “alive”. Lynch enjoys using pre-existing pop songs or popular music to release the emotion of Americana nostalgia. American cinema always centres with the human body which is either acting or feeling, and the body is always linked to a concrete milieu; in Lynch’s case, is a concrete Americana that is able to transform through the intellectual reuse of the pop songs. The “Blue Velvet” song in Blue Velvet; “16 Reasons Why I Love You”, “Llolando (Crying)” and “I’ve Told Every Little Star” in Mulholland Drive, Elvis Presley’s songs in Wild at Heart (1990), are all great examples of using pre-existing pop songs to release emotions of Americana nostalgia, showing the dark underworld of the Americana imaginary.

In James Wierzbicki’s study on film music history, he discusses that postwar time is a critical time for the survival of the Hollywood: with the increasing competition from the booming American television industry as well as the European indie films, Hollywood had to “move toward divergence” and manage “new directions”. One of such postwar innovation for the survival of Hollywood is the use of pop songs and popular music as replacements to the full-time orchestra scoring, which intended to broaden the target audience and sell the pop song recordings for extra profit. From this aspect that using pop music is out of the market needs, David Lynch’s use of pre-existing popular songs is a departure from that. Instead for the market need, I would like to argue that the pre-existing pop songs in Lynchian world is a vibrant and sad representation of Lynch’s nostalgia for the Hollywood “golden era”. Lynch discussed this in many of the interviews that how he was “shocked” by the vibrant city life of LA the very first time he went there, and he “woke up in the morning and had never seen light so bright”. Lynch’s first encounter with Hollywood reveals Lynch’s initial affection and enthusiasm for it, which leads to his consistently ongoing passion for the depiction of Hollywood.

Apart from his initial affection for Hollywood, the Americana nostalgia also reveals through those pre-existing pop songs in many features. Wild at Heart is a great example in showing Lynch’s nostalgia for Hollywood with reference to its genre and music. This film follows the Hollywood clichés and conventions of road film: the extravagant adventures follow Indiana Jones (1981), the endeavour of the good witch are allusions to the classic musical The Wizard of OZ (1939), and Lula and Sailor’s hotel room resembles the room separated by a sheet in It Happened One Night (1934). Apart from following the tradition of Hollywood road film, the use of Elvis Presley’s songs also reveals the nostalgic Hollywood to a greater extent. Lynch’s use of “Elvis Presley rock-musical Hollywood ending” depicts the annihilation of the American dream and “mourns the watershed of the American fifties”. This road film traces along the development of American dream for a half century–Sailor and Lula’s adventure starts from the “new-frontier” and explore towards the unknown West (“a diminished new place”) from which we are presented an American domestic decadence. Therefore, throughout their road journey, “Love Me tender” functions as the emotional stanchion for the release of Americana nostalgia.

Moreover, according to Michel Chion’s notes, the rock and electro music used in Wild at Heart releases the powerful emotion and strong romance and integral to its theme structure, “stated from the outset by the very flamboyance of the credit sequence, just like a tonality is affirmed at the beginning of a symphony.” The “Cine-symphonic” music mixed up with low held notes and high powerful notes, idiosyncratically releasing emotions for Americana nostalgia through the powerful romance.

Another example of using pre-existing popular songs to release emotion of an Americana nostalgia is Camila Rhodes’s rendition of “I’ve Told Every Little Star Scene” in Mulholland Drive. “I’ve told every little star” originally introduced to the public through a musical called Music in the Air in 1932 and it has been recorded by many artists since then while the best-known version is Linda Scott’s hit in 1961. In the film, Camila Rhodes’s rendition is simply a dub of the Linda Scott’s voice, and from the previous film we have learnt that she is the actress who comes into Adam’s film via backstage corruption. When Adam says in a very affirmative voice “This is the girl”, he gives in to the “back case work”. In this scene, Camila Rhodes is an allusion to those whose success is from the backstage corruption and manipulation rather than the consistent hard work in Hollywood industry. In David Andrews’s study of what Michel Chion calls the “Cine-symphony” of Lynchian cinematic world, he discusses that the “related theme of doubling” (which is the “I’ve told every little star scene”), is integral to the disturbing centre of the Hollywood which reveals Lynch’s nostalgia for Hollywood, and this is in accordance with Todd McGowan’s argument that Mulholland Drive reveals perfectly Lynch’s “panegyric to Hollywood”.

Apart from the use of pre-existing pop songs which release emotion of his Americana nostalgia, the music transition used in Lynch’s films often functions as the passage to the desirable centre of the human body. Firstly, the transition between silence and music leads us to the desirable centre. In Mulholland Drive, the “Club Silencio Scene” is considered a critical scene as this is the turning point from where Diane wakes up and goes back to her “real world”. The song performed at the Club Silencio “Llolando” is a Spanish version of Roy Orbinson’s “Crying”, but it achieves very different effects in the film from Roy Orbinson’s original. Before Rebekah Del Rio starts her performance, she taps the microphone which “suggests that it is ‘working’”, and this is a sign signifying that her performance is “real”. This song “Llolando” tells the old Hispanic tale about the ghostly crying women mourning her dead children, and this indicates death happened in the second half of the film. At the Club Silencio, everything presented as an illusion and recording, so when Rebekah the performer falls off on the stage while the song is still on, Rebekah’s voice has transformed to an impossible object which is caused by Diane’s unattainable desire and fantasy. In Tom McGowan’s Lacanian analysis of objet petit a, he remarks that Rebekah’s voice function as “an impossible object”, and since the “desiring subject must recognize the impossibility of integrating the objet petit a”, when Rebekah falls off on the stage, we see Diane’s fantasy world collapses.

Rebekah’s voice is so catching and sad that both Betty and Rita cry with tears all over their faces, as they both feel the sadness from the lost objects. “In Lacanian psychanalysis, the voice is like the gaze, is the paramount lost objects, objet petit a.” This is a very moment that calls viewers to pay full attention just to the artistically magnificent performance; this is “an ethereal sequence that begs the viewer to engage in pure autotelic appreciation”. After the performer falls off, the blue-wigged lady reminds us again “It’s all an illusion”, and we go back to the reality with Betty. “Silencio” means silence, indicates not only everything unsaid is left in silence, but also everything is recorded is still left in forever silence. Therefore, in this Club Silencio scene, music transition between the silence and what we hear functions as Diane’s unattainable desire of her lost object and make Diane immerse in deep sorrow, striking her to wake up into her reality. Secondly, the music transition happened when the figure of desire enters into the stories reveals the obsessive and pathological desire of the human body.

As Anna Katherina Schaffner suggested in her gender and psychoanalysis studies, “Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire constitute a thematic trilogy, for they all explore obsessive-destructive desire, fantasy and paranoid-schizoid splitting of the female other into virgin/whore, wholesome woman/femme fatale, ideal/nightmare.” In Lynch’s films, the figure who seems to invade the world of someone who is driven by desires to know and to control is often presented indirectly to the spectators, and music transition is a vital element in generating and leading this figure of desire to the disturbing centre of desires to know and to control. In this thematic trilogy, music has an impressive and intense feature when these figures of desire enter the stories. In Lost Highway, when the mystery man first appears in the crowd and walks towards Fred, the party music starts to turn down and when he stops right in front of Fred, the diegetic party music suddenly stops. There was a silence before ominous non-diegetic music starts to emerge.

At this moment music enables us viewers to pull out from the partying crowd around, and search and get lost in Fred’s uncanny and uncertain subjective world. In Mulholland Drive, Betty is the figure of desire and generates the fantasy story with her investigation of Rita’s identification. At the very start of the film we see many couples dancing jitterbug in a supernatural background with shadows casting against the purple background. After the figure of Betty and her uncle and aunt shows up for a short while we see Betty appears from the white unnatural light of the dancing couples with overwhelmingly uplifting and big excitement on her face, catching full screen’s attention. Betty wins the jitterbug competition; the jitterbug jazz music fades away and there is exciting diegetic applaud and cheering for her.

The transition from Jitterbug music to the applaud sound highlights Betty’s entrance into the fantasy story where she will start to invade her love object’ world with a desire to know and to control. In Inland Empire, the rabbit room is an allusion to young actress Nikki’s passage to her obsessive desire to know and to control her life which is caught up between the fantasy and reality. The noticeable transition of sound and silence here is achieved through the laugh track responses which indicate the life of the surrealist anthropomorphic rabbit family is being recorded and presented in front of the audience as a TV show. In this film, the sound of a gramophone playing Axxon N become one of the recurring motifs and occurs occasionally throughout the whole film, highlighting the entering the Nikki in her desire to search her unattainable love object. Therefore, the music transition between silence and sound, as well as when the figure of desire enters the stories, both lead us to the very centre of the desirable human body.

By focusing on the discussion of a few Lynch’s recent features as well as an awareness of his career trajectory, I tried to critically argue and present the idiosyncratic visual design and sound design of Lynchian style in the terrain of contemporary Hollywood. This research essay focuses on the discussion the “concrete abstraction” of Lynch’s film painting, the releasing emotion of Americana nostalgia of Lynch’s use of pre-existing pop music, and revealing of the desirable centre to know and to control of Lynch’s music transition, attempts to navigate into Lynch’s “panegyric to Hollywood” through the disturbing and powerful desires. Lynch as the new auteur in Hollywood with a span of over forty years in filmmaking, has developed his highly stylised Lynchian style in both visual and sound design, which always offers endless source for both the academic and the public to navigate in the Lynchian town and search and lost in the Lynchian world.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Was a huge admirer of some of his films, long ago, but I’ve never actually liked him, and got to the point where I find him a bit repellent

What a genius filmmaker. Easily in my top 10. How right he is when he says that the important when you make a film is “the idea that you’ve fallen in love with, and you try to stay true to that”. That’s the tougher in cinema, the making of the film always degrades the striking image the filmmaker had in his mind. But Lynch is one the few who managed to stay the closest to this purity, which is beyond words. I never get this people who always try to find interpretations and meanings inside Lynch films, when they should let themselves carry by the images and the sounds.

The only downside of his work is that his characters and dialogues are often rather poorly built. He is at heart a visual artist who moved to film for the purpose to add movement and sound to his aesthetic universe, and not a comedy/drama expert. That’s the reason why his films often come out as rather disorganized and chaotic. But that’s a very minor flaw compared to the richness and beauty of his universes.

I’m a huge fan of his work. Eraser Head is still the most harrowing experience, whereas The Straight story was good sustainance for the soul.

I don’t like Lynch’s film as a rule and after reading this article I don’t think I like him as an individual. But it can’t be denied he’s an incredibly intriguing man.

Intriguing yet dislikeable. I strive to be this.

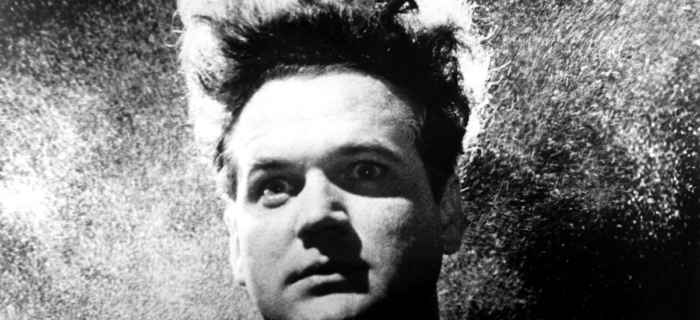

Eraserhead.

The only film that I have ever walked out of.

It was just too much.

Still a great film though!

Funny, that’s the only Lynch film I’ve ever really liked. Stuff like that’s why I could never make it as a full-time critic.

I view it primarily as a horror film based on familial embarrassment. The titular character is trapped with only the most bizarre, forlorn hopes as his escape.

It’s a film you experience only to leave traumatised.

Easerhead is a really startling, horrific but good film. I was talking about it last weekend, recommending it.

David Lynch is a fascinating film makers and artist. I love checking out his work, even if I don’t always understand it. Great Article!

Brilliant director. Twin Peaks changed tv for the better forever- eternal thanks.

That’s an overstatement.

One of my favourite scenes in Mulholland Drive is something most people wouldn’t notice…when Betsy first enters her apartment and the camera silently glides through the entire place. No sound…just a buzz. I love all these aspects in film and almost every film of his has that technical touch. It’s very atmospheric.

If you wanna see genius, watch the Diner scene in Mulholland Drive. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UozhOo0Dt4o

You don’t need to know anything about the movie, it’s in broad daylight but its tremendously dark and full of tension. Lynch is spectacular here.

How about the nightclub scene in Fire Walk with Me for dark and full of tension? That horrible music and the barely audible dialogue. Pure brilliance.

After waiting 25 years for something better than the original twin peaks I was disappointed. It had flashes of brilliance and chances to make me fall in love again, but ultimately I was deflated. We were all dragged kicking and screaming into his world, but so few of us want to reside there.

I agree. I thought the new Twin Peaks was self-indulgent, directionless and lacking in any meaningful content. You can tell when a writer or director has really made it and been given carte blanche to do what they like, because you end up with this kind of turgid stuff. Obviously now no one dared to tell him that it needed to be cut (massively) and it needed some kind of coherence.

It also made the mistake of over-explaining: trying to tie everything vaguely to the atomic tests of the 1950s. This is his midichlorians moment. Sometimes a mystery is best left as a mystery.

A great fan of David Lynch’s work, I finally got round to watching “Mulholland Drive”. There is a turning point in the course of the film where everything appears to be thrown up in the air and any assumed understanding of the multiple strands plot, disappears. It’s the point where someone may justifiably scream “What the hell is going on?”. Persevere and you will be rewarded!

Not everything makes sense, some scenes in my view are meaningless in terms of plot relevance, such as the cowboy random appearances, the reckless and clumsy contract killer shooting mistakenly through a wall and carries on killing irrelevant people, the bizarre espresso coffee spitting scene, the young man with the dream-come-true fear at Winkie’s, but curiously enough they don’t appear to be out of place in the film. I am sure seasoned cinematography critics out there can explain these easily but in my view the film is a fantasy, a dream with some nightmarish undertones. And, in dreams or fantasies we don’t have to explain everything. In most cases we wouldn’t be able to, anyway!

What came to mind as I was watching Diane/Betty moving along the non-linear flow of the film, were notions of innocence, aspiration, love, passion, failure, reality, disappointment, jealousy, hate, envy, rage, vengeance, remorse, retribution, (old couple resembling the goddesses of retribution, Erinyes, tormenting the wrong-doers). Do these words bring to mind the human condition?

Not the mainstream feature film but it wasn’t meant to be. It challenged me immensely but in a nice way, tantamount to that of trying to solve an engrossing riddle or puzzle. Have I fully understood what was really intended by David Lynch? Most probably not, but I believe I have arrived at a conclusion good enough to make me appreciate this masterfully made enigmatic Sapphic thriller. I enjoyed it and that’s what matters to me.

It could be considered as the second instalment in a trilogy of psychological dream-like mystery thrillers, with the first being “Lost Highway – 1997” and the third “Inland Empire – 2006”.

I think the best thing about Lynch’s work is the dark (extremely dark) humour that pervades his work. Much like postmodern art, I’ve never found his films to say much that is profound – only bitingly satirical to the point of farce. Still loved Blue Velvet and Lost Highway. Twin Peaks not so much.

Like a true artist, Lynch is divisive, difficult and disturbing. One of his particular tropes is finding the darkness in the otherwise healthy and light. Smalltown white-picket fence America hides Blue Velvet’s nightclub weirdness. The lovely Hollywood dreams of Mulholland Drive are just a short nap away from nightmares and noir killers. The tragic and doomed John Merrick is first a circus freak, then paraded again before the Victorian medical great and good. Even in the obstensibly Straight Story, there’s roadkill, pregnant teenage runaways and shotgun blasts. A great American artist, who helps us to see beyond, deeper and further.

Wish I had a head of hair like that.

I presume it takes a lot of meditation

One of my favourite directors. Unique, meticulous and intriguing.

An enjoyable essay on a director I knew little about.

Great article! I really love Lynch’s work, and I am always glad to learn new stuff about it!

The day I will be fully able to understand Twin Peaks is going to be the most glorious in my whole life.

Eraserhead haunts my nightmares, that’s all I have to say.

Lynch constantly plays with the idea that America has been constructed to intentionally create a facade that evil can fester beneath, going unnoticed. There’s a critical commentary at work here of course, but there’s also a nostalgia for this system, which elevates all of his pieces away from didacticism into complex swirling portraits of the American psyche.

Holding in your hands the (seemingly contradictory) ideas that the system is rigged while also having an unwavering admiration for the system’s iconography and culture. THE American filmmaker, in my opinion.

Hello! Great article. I just wanted to ask about the section where you talk about “determination of technical materiality of its existence”. I don’t quite understand that section. Could you elaborate more on it? Also how do you define “determination of technical materiality of its existence”? I’ve looked at that phrase over and over again and can’t discern what it means.

It is just sad that sometimes people are known for something they pick up as a means for survival rather than what they set out to do. Lynch’s nostalgia for old Hollywood also meant disillusionment for Hollywood cinema: he was a painter at the beginning, and he missed his old Hollywood. By the way, I wouldn’t call Lynch a “new” auteur – he has been around for decades! 😉