The Diary of a Madman: Madness and its Ability to Explain Reality

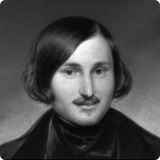

In a work of literature, anytime a character is deemed “mad,” we should be skeptical. Madness is never just madness for the sake of insanity. It is up to the reader to decipher the purpose of “madness.” For instance, the title alone of Nikolai Gogol’s short story “The Diary of a Madman” seems like it reveals all that the reader needs to know: the protagonist must be crazy, and we are most likely dealing with an unreliable narrator. However, in his article “The Suffering Usurper: Gogol’s Diary of a Madman,” Richard F. Gustafason states, “The ‘Diary of a Madman’ is not simply the story of a poor, insignificant clerk who is driven insane by the frustrations and humiliations received from the ranking figures in a powerful bureaucratic machine” (Gustafason 268). Indeed, Poprishchin’s “madness” is not just a reaction to his unfortunate circumstances, though his job of sharpening pens is certainly meaningless, and we cannot ignore that he makes little money and has no luck with romance. His “madness” exposes truths about the social climate in St. Petersburg and about the human condition more generally. Though Gustafason claims that Poprishchin is the creator of the “mad world” presented in the story, we can question if Poprishchin is really the creator or if he is the one to expose the world for being what drives him mad. The extent of Poprishchin’s “insanity” therefore remains questionable.

Defining “Madness”

First, we should define the words “madness” and “insanity.” Merriam-Webster defines “madness” as “a state of severe mental illness” or “behavior or thinking that is very foolish or dangerous” (“Madness”). In Poprishchin’s case, his ability to hear or see things that nobody else can (Gogol 275) and the fact that he comes to believe that he is the King of Spain suggests that there could be something medically wrong: he might be schizophrenic (Altschuler). However, the second definition, “behavior or thinking that is very foolish or dangerous,” could also describe Poprishchin, although he does not harm anyone or himself. Perhaps his delusions are not evidence of schizophrenia or some other type of mental disorder but rather evidence of the odd, eccentric way he copes with unfortunate circumstances.

“Madness” and “insanity” are often used as synonyms, but “insanity” is better used as a legal term, not a medical one. While the first Merriam-Webster definition of “insanity” defines it along the medical terms of “madness,” the second definition states that “insanity is an “unsoundness of mind or lack of the ability to understand that prevents one from having the mental capacity required by law to enter into a particular relationship, status, or transaction or that releases one from criminal or civil responsibility” (“Insanity”). However, Poprishchin is not formally charged with any crime, though he ceases to go to work and frightens people with his claims of royalty. Nevertheless, he is deemed insane by the establishment and locked up in an asylum by the story’s end.

But do any of these descriptions really describe Poprishchin’s actions? There is no doubt that his state of mind trends towards the strange and arguably deranged, but we cannot say for certain that he is schizophrenic. Whether Poprishchin has a psychological disorder or he is in fact driven insane because of his circumstances, we should not be so quick to label him crazy and disregard everything he says, as he is able to convey bits of truth and reality to the reader.

Glimmers of Sanity and Reality

The story is written in the form of a diary, and the only point of view we receive is Poprishchin’s. However, he reveals much more to us than the events of the day or his inner thoughts. As he is considered “mad,” we must sort between the ramblings and the truths. In the first diary entry, dated October 3rd, Poprishchin admits that his sudden ability to hear dogs talk and the fact that they can write letters surprised him. However, in the entry dated November 11th, Poprishchin states, “I’ve long suspected dogs of being much smarter than people; I was even certain they could speak, but there was only some kind of stubbornness in them. They’re extraordinary politicians: they notice every human step” (Gogol 279). Poprishchin’s admittance that it is strange for a man to be able to understand animals does not ensure his sanity, and yet it is through the dogs that he learns truths that ruin his view of the world.

On November 12th, Poprishchin steals the letters from the dog Fidéle. He follows the dog home and after he knocks on the door, he charges in and snatches up the letters from the dog’s basket. The letters reveal that the director of his department, a man he idolizes, is no god to be worshiped, as he is as ambitious as everybody else (Gogol 282). The letters also reveal that the director’s daughter Sophie, with whom Poprishchin is infatuated, is in love with someone else (Gogol 284). The dogs reveal not only the state of Poprishchin’s mind but also cold truths about reality. However, the most scathing information that is revealed in the letters is what Sophie thinks of Poprishchin. Sophie’s dog, Medji, one of the letter writers, states that the clerk who sharpens pens in the director’s study has hair like hay and looks like “A perfect turtle in a sack” (Gogol 284). But the worst part of the letter reads: “Sophie can never help laughing when she looks at him” (Gogol 285). Poprishchin claims that the dog is lying and even accuses his boss, the section chief, of orchestrating the lies.

Though the reader assumes that the letters do not exist (Gustafason 271), the knowledge of reality found in the letters is knowledge that had previously eluded Poprishchin. We, as the reader, can assume that the letters contain the truth. The letters confirm Poprishchin’s belief that dogs are privy to information that humans are not. We must assume that no matter how Poprishchin attains the information, through dog- written letters or not, he remains unable to reconcile the “true” reality contained in the letters with his own notions of reality. As the reader goes through the diary, he or she is able to sort through Poprishchin’s “madness.” On some level, Poprishchin may be aware that his notions about life are not true. We still find bits of reality trickling through the cracks of his mind, as some of Poprishchin’s complaints about society sound sane and rational.

Challenging the Social Order

Despite all this talk of “madness,” Poprishchin reveals the fallacies of placing immense importance on having and earning rank in Russian society. The Table of Ranks, instituted in 1722 by Peter the Great, was a way to take power away from the ruling classes and give everyone a chance to serve his country and gain status, through civil, military, or court service. An individual can move up through fourteen ranks, fourteen being the lowest and one the highest (Galushko). Hence, Poprishchin views rank as an important marker of status and identity, and he is not necessarily crazy for thinking so: “Each rank came with accompanying rules for carriage, dress code, and honors. If anyone demanded greater laurels than appropriate for his or her rank, he or she were to be punished in the amount of two monthly allowances” (Galushko).

Though his boss, the section chief, tells Poprishchin that he (Poprishchin) has not done anything with his life, and he is past forty-years old, Poprishchin writes in his diary: “Am I some sort of nobody, a tailor’s son or a sergeant’s? I’m a nobleman. So, I, too can earn rank” (Gogol 277). According to himself, he is not a “nobody.” He claims to be a titular councilor (though this might be false), which is rank grade nine in the civil ranks. He takes his rank with pride and believes that he can be promoted and achieve the respect and wealth that he desires.

However, the importance he places on rank is shattered when it is revealed that Sophie is in love with a kammerjunker (which is the equivalent of a valet or manservant and court rank eleven). Poprishchin does not draw attention to the fact that he technically has a greater rank than the kammerjunker (this could be an instance in which Poprishchin the unreliable narrator dominates the story; he may not even have a rank), but in his December 3rd entry, he writes “So what if he’s a kammerjunker. It’s nothing more than a dignity; it’s not anything visible that you can take in your hands […] His nose isn’t made of gold, it’s the same as mine or anybody else’s” (Gogol 285). Even though people, aspire to earn greater and greater rank, the differences between each rank do not appear large or tangible in any meaningful way. Poprishchin is torn between knowing that attaining rank means nothing and believing that having a greater rank will bring him a better life.

In his December 3rd diary entry, Poprishchin also wonders why he is a titular councilor and what makes him such: “Maybe I’m some sort of count or general and only seem to be a titular councillor? Maybe I don’t know myself who I am” (Gogol 286). The arbitrariness of the social order affects him greatly, as the link between his rank and his identity unravels. He also draws attention to the superficiality of ranks: “Suppose, for instance, I walk in wearing a general’s uniform […]–what then?” (Gogol 286). By suggesting that dressing differently will make a difference on his station in life, Poprishchin reveals the shallowness of having rank, if it is not determined by anything substantial.

Madman or no, Poprishchin decides to rebel against the arbitrariness of the social order by claiming that he is the King of Spain. As soon as he decides he is a king, the dates of the diary become erratic: one entry is marked the 43rd of April (Gogol 287), another the 86th of Martober (Gogol 288), and one day simply has no date (Gogol 290). By making up his own days and months, Poprishchin also reveals to us the arbitrariness of time, time being another way to order and organize the world. Additionally, he does not go to work for a few weeks, and when he finally does return, he learns that the director he once idolized is coming to the office. Poprishchin, however, does not bother to line up to present himself like the other clerks because he believes himself to be a king (Gogol 288). He thinks he can upset office decorum by going against the norm.

However, when Poprishchin is taken to the asylum, order is restored. Though he thinks he is taken to Spain and subjected to the Inquisition (Gogol 292), Poprishchin opens our eyes to the way society structures life and favors some people over others. In the very last diary entry, it appears that Poprishchin has regained some lucidity. The ill-treatment he receives in the asylum causes him to cry out for help, at one point calling for his mother, writing, “there’s no place in this world for [your son]! they’re driving him out!” (Gogol 293). He seems to be acknowledging the fact that his attempt to be more than society has made him out to be has failed, and his future is bleak. However, the very last line of the final entry, “And do you know that the Dey of Algiers has a bump just under his nose?” (Gogol 293), reveals that the moment of lucidity has passed, and Poprishchin has returned to believing that he is more than he really is.

We are certainly meant to read Poprishchin as a madman, as the title suggests. And of course, we should take most of what he says with a grain of salt. His anger at society and his desperate attempt to imagine himself as a monarch of a foreign country is the ultimate escape from his bleak life in St. Petersburg. And yet Poprishchin is able to draw important conclusions about identity and order. His own madness might stem from his inability reconcile his desire to earn rank and the meaningless of rank. Madness and suffering also seem to be a recurring theme in Gogol’s other Petersburg tales. In “Nevsky Propspect,” the falseness of the city drives the artist Piskarev to commit suicide because he cannot rectify the prostitute’s beauty with her callous demeanor and way of life. Would we call Piskarev “crazy” for cutting his throat over a prostitute? We might. Or we might feel sympathetic to his plight. It seems as if there are varying degrees of “madness,” medically or legally, and both Piskarev and Poprishchin belong somewhere on this spectrum. Therefore, we can refrain from labeling them “mad,” and we should not regard Poprishchin’s diary entries as mere ramblings. There is more to his madness than the loss of sanity, as we are able to learn from it. Anytime a character has his or her sanity cast in doubt, we should always question if there is more to the madness than just madness.

Works Cited

Altschuler, Eric Lewin. “One of the Oldest Cases of Schizophrenia in Gogol’s “Diary of a Madman.” BMJ: British Medical Journal. 323.7327 (2001): 1475-1477. Web. 22 May 2014. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/25468632>.

Galushko, Irina. “Of Russian Origin: Table of Ranks.” Russiapedia. RT.com, n.d. Web. 22 May 2014. < http://russiapedia.rt.com/of-russian-origin/table-of-ranks/>.

Gogol, Nikolai. “The Diary of a Madman.” The Collected Tales. Trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998. 273-293. Print.

Gustafason, Richard F. “The Suffering Usurper: Gogol’s Diary of a Madman.” The Slavic and East European Journal 9.3 (1965): 268-280. Web. 22 May 2014. .

“Insanity.” Merriam-Webster. Web. 22 May 2014. <http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/insanity>.

“Madness.” Merriam-Webster. Web. 22 May 2014. <http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/madness>.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Hello, I enjoyed reading this article a lot. You have a smooth writing style and the subject material was very interesting. I especially like how you displayed the dichotomy between madness and insanity, intriguing stuff. I will have to put “The Diary of a Madman” on my to-read list.

You bring up an interesting topic especially with Gogol, more often than not Dostoevsky’s Notes from the underground is chosen, yet it is difficult to assess the work through your use of lexical definitions. Wouldn’t philosophically nuanced definitions be more useful? Where exactly do you show madness and its ability to explain reality, aside from claiming that it does? Your treatment of Poprishchin doesn’t make a clear case that madness illuminates social realities. Couldn’t the case just as well be that his poetic insights into reality preceded his madness? Or are you only discussing works expressed in madness as containing truths? If that is the case then, do we also need to be mad readers to see them?

I’m interested in what a more philosophically nuanced definition of madness would be. It could very well be the case that Poprishchin is driven mad by the reality around him. I don’t think the story makes it clear. I was hoping to explore madness as something more than madness when it appears in literature. Characters aren’t simply mad for no reason, but whether or not they elucidate truths or reality to the reader is debatable.

I read two of his short stories, The Diary of a Madman and The Quarrel. They were both really good short stories, and I will hopefully be reading more of Gogol. I really enjoyed his character development of the two Ivans in The Quarrel, it adds depth to their petty argument. The Diary of a Madman is just fantastic. I love how the dates are written as his insanity becomes more prominent and I love how he believes he is the King of Spain and why no one will respect him for that.

Honestly I thought it was very depressing with not a lot of meaning to offset the bleakness.

Eat your heart out, Kafka!

At my university they have a class called Literature and Madness. This article really makes me want to take it. Great job, all your examples were awesome.

Thanks for the compliment!

Brilliant short story told from the point of view of a man who is slowly going insane. As the diary entries progress, so does the man’s insanity. He imagines conversations between dogs (in letter form) and declares himself the new king of Spain. What starts off as amusing, peculiar and a bit hilarious segues into a lonely sadness.

Tragic… comic… but it’s a fantastic portrayal of schizophrenia.

I’m fond of the unreliable narrator concept and don’t usually assume characters know the entire truth or would speak it if they did. Assuming an unreliable narrator changes the meaning and tone of a lot of fictional works (and non-fiction ones, come to that). In this particular case, the narrator may be mad, but still reliable in many aspects, which is a dichotomy I find fascinating. Interesting topic!

Very interesting. I’ve found that I often most enjoy novels/stories that have to deal with a character’s decent into madness.

Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night anyone?

I will have to put this on my to-read list (which just keeps growing the longer I’m on this site!). Thanks so much for your insightful piece, very enjoyable to read.

Wonderful article exploring the implications of insanity/sanity in literature. I would love to re-read those great “mad” figures (Ophelia, Lear) of the Bard again using your analysis of Gogol.

It’s a goods article but you have a problem. Kammerjunker is higher in ranks than the narrator. Therefore his belief in ranks is OK.

This sounds like the darkened version of Gulliver’s Travels, particularly the fourth book.