Disney and Disability

As the twenty-first century enters its second decade, Disney has undergone huge changes. The company has made huge strides in promoting racial, familial, sexual, and other types of diversity. From the Black protagonist of Doc McStuffins and the vampire family of Vamparina, to the queer characters of Luca and the princesses without princes in Moana, Brave, and Raya and the Last Dragon, diversity is a hot topic. “Different” means “positive,” “unique,” and “possessing a needed perspective.”

In the midst of the diversity and inclusion conversation though, one group is consistently silenced. Especially in the last decade, people with disabilities have not been represented adequately in media. Of course, Disney is not the only media conglomerate with this issue. People with disabilities (PWDs) have pushed for better, more nuanced, and less inspirational, representation across media for decades. But Disney stands out because it is so ubiquitous. It’s a part of life for millions of people, beginning in earliest childhood. Thus, if a child sees a Disney character who is “like them” in not only personality, but also skin color, orientation, or another type of diversity, that child feels seen. That child learns there are real people in the world like them, and they deserve representation and voices in the world.

Disney has hosted many disabled characters, or those coded as disabled, throughout the years. As we will see in our discussion, the presence of characters with disabilities is not an issue. The issue is that, even though characters with disabilities exist, their disabilities are not named as such. The disabilities are not allowed to be a major part of the characters’ stories or their growth. In some cases, disabilities are presented as negative or a symbol of lack. Characters who have named disabilities, such as Massimo in Luca, are secondary to non-disabled characters. Others have named disabilities, like Nemo’s “bad fin,” but are not allowed to explain them, take autonomy over them, or experience life with them alongside non-disabled peers.

Disney’s current trajectory shows they are trying to include characters with disabilities more in their stories. Yet, the company seems confused about how to do that, while also coming out and saying, “This character is disabled and that’s a legitimate part of their identity and story.” Outside media has responded accordingly. For instance, a New York Times story on Massimo says in the headline that the character “doesn’t let disability define him.” The intention is positive, but the phrasing also indicates, “To acknowledge disability is to define by it, which is negative. Disabled people should not speak of their disabilities.”

If Disney, and in turn other media, wishes to repair this issue, they should look at disabled and coded characters of their past. These characters may not identify as disabled, but their personalities and stories can teach a lot about how to handle disability in the fictional realm–or how not to handle it. The Disney canon gives us several examples to analyze, and lessons to take from each one.

For the purpose of our discussion, we will use either persons with disabilities (PWDs), characters with disabilities (CWDs), or “disabled people/disabled characters.” This reflects the disability community’s experience. Some of us are comfortable with “person-first language,” as it acknowledges personhood first, with no labels of any kind attached. Others of us prefer “disabled” and call ourselves such, out of a desire to remove the stigma from the word and avoid patronizing alternatives like “handicapped,” “differently abled,” “handicapable,” or “challenged.” We will also use “able,” “abled,” or “non-disabled” to refer to persons without disabilities, as these are the common words used in the disability community.

A character is considered disabled if they have a visible or named disability or a representation of such (Nemo’s fin being analogous to a leg, for instance). A character is “coded” disabled if they are never called such or do not have a named disability, but show traits or mannerisms that reflect a certain disability. This is more common with invisible disabilities such as autism or other forms of neurodivergence.

Ariel: Tie Disability to Positive Characteristics

Disney’s first disabled character came onto the scene long before the diversity and inclusion conversations of the 2020s. Ariel, the eponymous Little Mermaid, graced our screens in 1989, heralding the Disney Renaissance. The scarlet-haired mermaid with the melodious voice gave viewers a different kind of Disney princess. Unlike her forerunners Snow White, Cinderella, and Aurora, Ariel was fearless, independent, an explorer, and rebellious. And without meaning to, she became something of a representation of disability.

Throughout The Little Mermaid, Ariel longs to experience the human world. Later, she falls in love, or perhaps in infatuation, with human prince Eric. Her friends Flounder and Sebastian respond to this new love with a gift, a life-size statue of the prince. Ariel hides the statue in her grotto among her other human treasures, but her father King Triton discovers the cache. In a fit of overprotective rage Triton, who fears seeing his daughter “snared by some fish-eater’s hook,” destroys Ariel’s treasures. She’s left with a broken heart and the burned facial remains of Eric’s statue. Thus, Ariel becomes a prime target for sea witch Ursula, who promises to give Ariel exactly what she wants and thus, heal her heart.

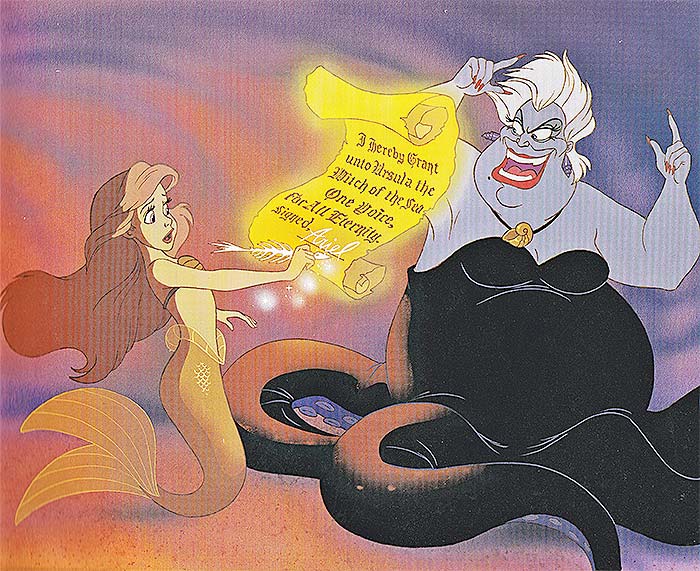

True to her reckless nature, Ariel is ready to do anything to become human and unite with Eric. Ursula offers her a deal in which Ariel can become human for three days and remain so permanently if she can get “the kiss of true love” from Eric. In true villain fashion though, Ursula will not give without taking. She insists on taking the one thing that might be more precious to Ariel than her human world dreams–her voice. Ariel agrees, even signing a contract stating that if she fails, she will forever belong to Ursula.

Many viewers, especially women, lose all respect for Ariel at this point. In her choice, they rightly see an anti-woman, anti-feminist message: “It’s okay to give up your voice, not only for men but for whatever superficial things you might lust after in the moment.” They see Ariel’s voice not only as literal, but figurative, connecting it with the plights of real women who have given up voices, choices, and autonomy in one way or another. Alongside those messages exist another layer. Said layer contains messages about disability, what it means for Ariel and what it could mean for real people, especially girls.

Muteness: A Minor Inconvenience?

Once Ariel loses her voice, she becomes disabled. She can no longer communicate with her mouth, so she must rely on gestures (or, as Ursula crudely put it, “looks…[and] body language.”) Our intrepid princess gives new communication a good try and succeeds somewhat. Eric takes her into his castle and allows her to stay as a guest, giving Ariel a needed “in” so she can build a bond with him. Overall though, Eric has to guess at what she wants to say. Sometimes he gets it right, at least a bit–when they meet, he discerns from her gestures that Ariel needs help. But because Ariel has never had to communicate without her mouth, nor had learning opportunities for it, her communication is ineffective. Eric ends up thinking she’s a random girl washed up from a shipwreck, but not the arresting, memorable singer who saved his life during a hurricane at sea. His staff reacts accordingly; they have no clue, or reason to think, that Ariel is their prince’s mystery lady or in love with him.

During Ariel’s muteness, she’s treated more like a curiosity than a person. Eric’s housekeeper and butler Carlotta and Grimsby are kind, but tend to hover over her like she’s a distressed child. Grimsby even calls her “child” more than once, and Carlotta tends to call her pet names like “honey.” Granted, Ariel does things like trying to comb her hair with a fork or “play” a smoking pipe like a musical instrument. And of course, there is no way Eric or his staff would make the connection that Ariel doesn’t know these objects’ purposes because she’s a mermaid. Still, they tend to laugh indulgently at her and perhaps assume she’s mentally deficient. When they don’t understand Ariel’s attempts at communication, Eric and his staff simply move on, ignoring her or assuming she meant something she didn’t. The message becomes, “Ariel is a new ‘pet’ whose muteness can be funny or sweet, but is largely inconvenient.” It’s a negative message for real PWDs, too, who are often infantilized, ignored, or misunderstood. The negative message for abled viewers is, “It’s okay to react to disability like this, as long as you are compassionate about it.”

Muteness as Relief

Ariel may be coddled and infantilized, but she does get to experience the human world while in Eric’s kingdom. In a memorable montage, Eric takes her on a tour. Viewers see them enjoying a puppet show, baked goods, and flowers together, and dancing in the town square. They also get to see Ariel driving a carriage and loving every minute–while a terrified Eric hangs on for dear life. The culminating boat ride caps off one of the most heartwarming parts of the film. Better, the scenes give viewers hope that, while Ariel has literally never conversed with Eric, their love is becoming real.

In a way, Ariel’s time as a disabled woman is positive. Because she’s mute during her time as a human, she shows disabled people in general can have experiences on the same level as their abled peers. She shows they can enjoy life, and do not need fantasy worlds like the mermaid world to do so. Additionally, Eric’s blooming attraction shows PWDs are worthy of love and can receive it. Eric is willing to engage with Ariel far before she can speak, and even before knowing her name. As far as we know, he never pressures her to speak or tries to analyze her muteness. This may be because he believes it’s temporary; recall he thinks Ariel survived a shipwreck and is thus a trauma victim. Temporary or not though, Eric shows a level of respect for disabled people that, while found in real life, doesn’t always translate into romantic relationships.

However, close analysis reveals the negative messages continue while Ariel and Eric build their love. Nostalgia Critic Doug Walker found the biggest one when, in his Little Mermaid review, he said he enjoyed Ariel more “when she’s not talking.” 1 According to Walker, when Ariel isn’t talking, she’s also not whining. She’s not obsessing over the human world, placing friends like Sebastian and Flounder in danger, yelling at her father, or acting rebellious. In other words, while mute, Ariel is not engaging in the negative behavior she did during the first half of her film. Walker even calls her big song, “pretty whining [when you get down to it],” because “Part of Your World” is all about what Ariel doesn’t have, how boring mermaid life is, and how she doesn’t deserve to be reprimanded.

One could argue then, that Ariel is actually a better and more positive role model as a character with a disability. Unfortunately, that argument has plenty of holes, and hurts Ariel’s representation. Namely, Ariel is only a CWD because of magic, and a deal she made herself. The disability itself came from a villain, not from natural causes or a benevolent mentor character who allowed Ariel to experience muteness with her best interests in mind. The implications then, are that disability is at best an unfortunate accident. No one would choose it, or if they did, would only do so if it were temporary. Furthermore, anyone or anything who would give or allow disability to a person, is malevolent. In some cases, people “did it to themselves.” And in some cases like Ariel’s, people need to become disabled for their own good, or to learn lessons. Doug Walker, for example, implies Ariel needed to become mute so she would stop whining and become a tolerable person.

As with the “disability is inconvenient” message, these messages tie into real life with discouraging frequency. People or characters with temporary disabilities, such as an athlete nursing an injury, are often more respected than people with congenital or lifelong disabilities. Some religions either imply or state outright that disability is a sign of disfavor from a deity. Religions that deny this are still more apt to see PWDs as objects of charity rather than real people. When a disability occurs, inside and outside religious communities, you might hear talk of what the person can learn from it, what a deity is trying to teach, or how the disability is “inspiring.” The same abled people who call the disability itself inspiring are also likely to decry its effects as unfortunate or burdensome. Some organizations such as Autism Speaks have taken this attitude to its extreme, describing autistic and otherwise disabled people as “broken,” “missing,” or “poisoned.” You could say Autism Speaks takes a bad cue from Ariel in calling their clients “voiceless.”

The worst part of The Little Mermaid’s “Muteness as Relief” message though, is the implication of Ariel as a better person when she’s disabled. Again, the implication can be and is applied to real disabled people. That is, some people privilege non-disabled bodies and minds. Others, however, find disability attractive, not because it’s part of diversity, but because it allegedly means the PWD is disadvantaged in some way. Thus, the PWD either needs an abled person as a caregiver or, in a case like Ariel’s, is more tolerable because they can’t do something (someone who’s mute, for instance, can’t argue or protest, even if they should). Additionally, this implication takes Ariel’s voice–the seat of her greatest talent and joy, and a huge positive part of her character–and turns it into a negative. In other words, for CWDs and the corresponding real people, disabilities make every facet of them negative.

Muteness as Unacknowledged Disability

The final but most significant problem with Ariel’s representation is, she’s not actually represented. Ariel is given a temporary disability in muteness, but no one actually calls her mute. Note that this is different from coding Ariel as disabled, for a few reasons. One, muteness is an actual, recognizable disability. Two, muteness has facets like any other disability–every disabled person is different, even if two disabilities are the same. But those facets aren’t explored in The Little Mermaid, and there is not a mix of easily recognized and more nuanced traits within Ariel’s muteness, as there would be with disabled coding. Three, Ariel can’t be considered coded mute, whether she actually is or not, because when she has a voice, she doesn’t express or experience “muteness.” She complains of being misunderstood, reprimanded, and held back, but she never equates those experiences with losing her voice or otherwise being disabled.

With Ariel then, Disney gives us a character who has all the potential to experience muteness on two levels, yet never acknowledges it. She seems almost detached from her vocal loss, in that she recognizes it as an obstacle but doesn’t let herself deal with it. She doesn’t consistently try to communicate with Eric, nor does she seem to have avenues for that. She doesn’t acknowledge that muteness is keeping her from what she wants or needs, or that she has felt muted or silenced even with a voice. Her primary relationship with her disability is, “If I get Eric to kiss me, Ursula will be defeated. She, and this inconvenient vocal loss, will go away. I’ll never have to consider it again.”

Once again, the message and implications toward real PWDs are negative. Some people with disabilities may report a detachment from their disabilities, or a desire not to talk or think about them. But particularly in the 2020s, disabled people are working hard to craft positive identities that include disabilities. Situations like Ariel’s just reinforce, “It’s best not to think of yourself as disabled, or talk about being so. If you do, you are acting like a victim.” In some cases, the envelope gets pushed further, as disabled people are encouraged to strive more, work harder, and prove themselves among their abled peers. Some people with disabilities encourage each other to be “voices” for their groups. While they mean well, these people forget, again, that PWDs are individuals and everyone should get a voice.

After watching The Little Mermaid, someone analyzing for disability representation will recognize Ariel as an example of everything not to do. However, Ariel is still a valuable part of our conversation because of what she could and should have been. She should’ve been an intrepid princess who learned maturity through her whole journey, not just a disability that made her “better.” She should’ve been a curious, creative person who dealt with muteness using those traits to her advantage. Later Disney characters would have more of these traits and more opportunities to show them. Whether it was a conscious decision, Ariel became a sort of Disney template. And while she made a lot of missteps, Ariel is a trailblazer in Disney disability representation.

Quasimodo: Mix Grit and Hope

Disney gave us its next disabled character in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, which premiered in 1996. With this film and representation, Disney made a huge leap away from Ariel. Protagonist Quasimodo is not only a character with a disability, but the titular character, whose disability is acknowledged from minute one of the movie. Of course, it wasn’t right to call a disabled person a “hunchback,” in Quasimodo’s era or now. But considering said era (the corresponding Victor Hugo novel is set in 14th-century France), the word is understandable, although the representation tied to it is often dark and negative.

Quasimodo is another innovator for representation of PWDs, much more so than Ariel. Not only is his disability acknowledged up front, he has multiple disabilities. The “hunchback,” probably a spine curvature, is the first and most widely remembered. In addition, Quasimodo has craniofacial deformities. They’re described as grotesque in the Victor Hugo novel; in the Disney version, they’re toned down so Quasimodo has a swollen and protruding eye (which would then impede his vision). The Disney version makes no mention of Quasimodo’s deafness, and he speaks without sign language or the typical cadences of deaf speech. However, it would not be completely out of line to assume some deafness exists, since it is neither confirmed nor denied, and Quasimodo’s work as a bell-ringer could damage his hearing. The Disney version also adds an invisible disability; Quasimodo experiences deep social anxiety, and possibly Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. At times, his interactions and phrasing seem childlike; this could be either an effect of the above, or a sign of mild cognitive delays. Yet, all these disabilities never feel piled on, or as if Quasimodo is meant to be a poster child or pity object. Rather, Quasimodo accepts them as part of who he is, unless someone else tells him otherwise. One reality is that Quasimodo is visibly different from typical people, and is an outcast in his time. But the other reality is, Quasimodo is capable, has made a world for himself, and is primed for a hero’s journey.

The Dark Side of Disability

The Hunchback of Notre Dame doesn’t hesitate to show how disabled people can be maltreated and misunderstood. Quasimodo’s very name is a prime example, as it means “half-formed.” Worse, that was arguably never his intended name. It was forced on him thanks to Judge Claude Frollo, the movie’s villain and a staunch ableist (one who expresses bigotry toward disabled people). In the prologue, Frollo takes one look at Quasimodo and immediately takes him to a well to drown him. “This is an unholy demon; I’m sending it back to hell where it belongs,” Frollo says when the Archdeacon confronts him. Frollo’s cool, indifferent tone indicates he expects the Archdeacon to agree, perhaps nodding at unfortunate attitudes of the Church at the time.

In a pro-life and pro-disability move, the Archdeacon calls foul. “See the blood you have spilt…you never can…hide what you’ve done from the eyes of Notre Dame,” he sings. Shaken and in “fear for his immortal soul,” Frollo asks, “What must I do?” The Archdeacon orders him to take Quasimodo and raise him as his own, clearly intending the priest to become a repentant, loving guardian. Instead though, Frollo does the minimum for Quasimodo. He provides for him physically, but in ways that underline inferior status. Frollo has free access to Notre Dame and all Paris; Quasimodo is banished to the cathedral bell tower and never allowed to leave. Frollo expects Quasimodo to serve him complete meals including fruit and fresh bread using silver tableware. Quasimodo gets scraps he serves himself on wood. Frollo rests comfortably in assurance of salvation. He makes Quasimodo repeat alphabet lessons that focus on hell and damnation. If Quasimodo has multiple disabilities, he also faces almost every indignity a real person with disabilities might. Frollo’s status as Quasimodo’s caregiver makes this worse; in real life, many PWDs face terrible abuse from caregivers, up to and including murder.

If it were only Frollo who abused Quasimodo, we might be able to leave this section here. We could hand-wave it as expected of Frollo because he’s the villain. Unfortunately, Quasimodo’s Paris takes plenty of cues from Frollo. When Quasimodo does venture out of his tower to attend the Festival of Fools, he’s almost immediately made a fool. He’s praised, cheered, and honored–for his ugliness. The festival crowd ends up half-stripping him, tying him to a revolving wheel, and throwing rotten food at him. A lot of said food hits Quasimodo’s exposed flesh. When he begs Frollo for help, the guardian refuses, on the grounds that Quasimodo needs to learn a lesson after disobeying. Note here, Quasimodo is at least twenty years old. He’s an adult being treated simultaneously as a naughty child, and a bad person for expressing a desire for the independence his contemporaries get because they’re alive.

Frollo and even some sympathetic characters contribute to disability’s dark side throughout the rest of the film. When Quasimodo is back in the bell tower, with no intention to disobey again, Frollo continues gaslighting and psychologically abusing him. When Quasimodo tries to explain the Roma, or “Gypsies,” are not all evil after meeting Esmeralda, Frollo points out Quasimodo’s mother was a Roma. “When your heartless mother left you…anyone else would’ve drowned you,” he says, planting seeds that Roma are evil, Quasimodo is of evil lineage, and Quasimodo only deserves to live in the context of pity. Frollo later points to Quasimodo’s alleged naivete and inability to cope in the world as a reason he should quite literally be stabbed in the back.

As for Hunchback’s more sympathetic characters, they’re not above ableism either, or at least underestimating Quasimodo because he is visibly disabled. Phoebus, for example, acts as if Quasimodo is Esmeralda’s sweet, somewhat cute friend or pet, rather than a friend who happens to be another man, with all the needs and desires being a grown man entails. Even when Quasimodo pins Phoebus against a wall, Phoebus isn’t impressed with his strength. Rather, he’s intimidated and shocked, in the sense of, “I didn’t expect such skill from someone like you.” Granted, Quasimodo meant to come off that way. His strength, plus his repeated, truncated yells of “No soldiers! Sanctuary!” make him seem more caveman or beast-man than man. But Phoebus’ overall attitude is a bit awkward. This is especially true because in real life, some PWDs, especially males, are seen as aggressive just for standing up for themselves.

Esmeralda, too, gets a bit of this awkwardness in her character. A lot of viewers, abled and disabled, dislike her. They feel she rejected Quasimodo just because Phoebus was the more attractive and conventional man. Whether this is a problem is up for discussion, in that saying Esmeralda had to choose Quasimodo strips them both of autonomy (Esmeralda doesn’t get to choose; Quasimodo might not otherwise be chosen). What’s more problematic for Esmeralda though, is her view of Quasimodo in general. He is her friend, but she also refers to him as a “boy” or “poor boy” more than once (remember, he’s in his twenties). She shows true interest in Quasimodo, romantic and otherwise. Yet at times, Esmeralda also reads as his able-bodied savior, the one person in his whole life who ever has or ever would treat him like a human being.

Disability and the Community’s Story

Many Disney viewers eschew Hunchback based on these ableist attitudes, never mind the grit and potentially graphic content otherwise. Before we lock Quasimodo’s story in the bell tower of cancellation forever though, we’d do well to note the pro-disability messages hidden within. As with The Little Mermaid, Hunchback doesn’t give us “good” representation if what we mean by that is lack of ableism or other problems. But it does get a lot of elements right, namely Quasimodo’s role in his own story and his community’s.

When writers, filmmakers, and advocates talk about disability representation, they often complain CWDs have secondary roles in their own stories. Disabled characters exist to teach able-bodied people that “the disabled” are “just like them”; they exist to be perfect moral compasses; they exist to show that people like them exist and need basic kindness, if nothing else. Quasimodo though, is not secondary to his own story. Frollo victimizes him, but he doesn’t stay a victim. He’s cut off from Paris, yet he loves his city and would do anything to see it become what he knows it can be. Thus, Quasimodo’s journey is one not only of self and community acceptance, but of finding out where he belongs in his community. Note the question is not “if” he belongs. The film makes this a natural conclusion. Thus, Quasimodo is already one step ahead of a lot of disabled characters. He doesn’t have to prove he belongs; he and viewers know he does. Quasimodo’s journey is more about finding his niche and tribe, things that people of all ability levels need.

Quasimodo’s journey does progress through helping individuals like Esmeralda and Phoebus. As noted, those two characters can and do take his presence as a morality lesson. But for Quasimodo, the interactions are more about growth. With both Phoebus and Esmeralda, he faces his own prejudices–the one Frollo pushed on him about Roma, plus the innate prejudice against Phoebus as a soldier and a “normal” person. Facing his prejudice puts Quasimodo in a better position to relate to both characters, and open himself up more. He relates to Esmeralda out of infatuation from the moment they meet, but in helping Phoebus, he begins accepting the idea she can love him back, and love both men. As for Phoebus, Quasimodo opens his home and sanctuary when the latter is mortally wounded. This is a huge step, not only socially, but in growth as an adult, as Quasimodo defies Frollo, defies prejudice, and makes the unselfish choice.

Quasimodo also grows toward his community as he gets to know Paris, the city. At one point, Esmeralda gives him a woven band that acts as a subversive map; a simple cross shows Notre Dame’s location, blue threads are the River Seine, and so on. Quasimodo later uses the map to help Phoebus find safe passage through the city. He already navigates Notre Dame extremely well, physical disabilities or not. In venturing out, he expands those physical skills, such as climbing buildings and negotiating alleys or passageways. Even though he’s not interacting with people at that point, he is interacting with the physical city. As he does so, Quasimodo stakes a claim–“Paris is mine as well as theirs. I’m ‘out there’ like I wanted to be; I’m part of Paris now.” In fact, Quasimodo takes this knowledge as far as he can, going into the hidden Court of Miracles to save Esmeralda and her band from imminent harm, perhaps death.

The Court of Miracles scene doesn’t go well. Phoebus and Quasimodo are nearly hanged as spies, and Frollo blows the Roma’s cover, having followed Quasimodo to the Court. Quasimodo nearly succumbs to Frollo’s oppression for good when, seemingly because of his error, Esmeralda is sentenced to burn at the stake. But the tragedy of the Court of Miracles touches off Quasimodo’s most triumphant moments. Esmeralda’s near death gives him the final reassurance he needs that his benevolent “master” is an evil man. After saving Esmeralda, Quasimodo confronts Frollo for the last time. While his beloved Paris burns, Quasimodo declares, “Now I see the only thing dark and cruel about [the world] is people like you!” Thanks to skills such as his incredible strength and help from his magically sentient gargoyle friends, Quasimodo is able to fight off Frollo’s guards and save Paris, as well as his friends. He doesn’t directly cause Frollo’s death, but Quasimodo’s choice of love and light drive the villain to madness. This puts him in a physical and emotional position to die on both counts, so determined to “smite the wicked” with a sword that he loses his balance and topples from the cathedral. We’re meant to think Frollo died emotionally and spiritually too, having been condemned to hell.

After Frollo’s defeat, it seems Quasimodo will stay locked in his bell tower because it’s safe, and because the majority of Paris still sees him as deformed and abnormal. This may be why the last scene opens with Esmeralda and Phoebus, dressed in white, standing on Notre Dame’s steps together. Triumphant Parisians surround them, but Quasimodo is absent–until Esmeralda offers him her hand and the chance to come outside. Once he does, Quasimodo gains acceptance on a small and large scale. A little girl immediately goes up to hug him, and narrator Clopin touches off a celebration with, “Three cheers for Quasimodo!” Quasimodo is lifted to the crowd’s shoulders, doused with confetti, and legitimately celebrated as Paris’ hero, a positive role and one that shows he is now seen as valuable, lovely, and a human. He has completed an individual story arc, but is now part of the community’s story. Quasimodo’s Paris cannot exist without him, and now it doesn’t want to.

The Complexity of Creating Disabled Heroes

As a whole, Quasimodo’s arc is a well-developed example of a CWD’s story. That is, the character may start off as unaccepted or even bullied and oppressed, which is sadly true to life. Bullying.gov and similar sites tell us children with disabilities are at least twice as likely to be bullied as their non-affected peers. As for disabled adults, they are extremely vulnerable to hate crimes and other abuses. As with Quasimodo though, no character with a disability should stay oppressed if he or she is meant to grow. Quasimodo shows viewers how a person with a disability can successfully go from oppressed to befriended, befriended to accepted, accepted to self-determined and then to autonomous or actualized. In many cases, the character with disabilities can become a hero, not only as a protagonist but as a person who saves lives, places, or ideals. Depending on the story and character, heroism may need to happen.

Not all stories are as epic as Hunchback though, nor are they set in a time when inclusion should be celebrated because it’s so rare. Instead, Hunchback and Quasimodo offer viewers, and Disney in general, one more caution. It’s okay to craft a disabled person as a hero. To avoid doing so would be leaving PWDs out of a role they should have when appropriate, just like any other role in stories or real life. However, if not handled well, the “disabled hero” situation becomes one where the character is only accepted because they did something incredible. Many disability advocates and media experts caution against this, because it implies real disabled people are only valuable to the extent they can complete tasks or be useful to the abled world. It also implies disabled people must prove themselves, or “overcome disability” as much as possible (read: act as if it doesn’t exist).

Did Hunchback of Notre Dame avoid the heroism pitfall? As with who Esmeralda should’ve ended up with, it depends on who you ask. Regardless, the positives and negatives of Quasimodo’s story showed promise. They showed Disney was not afraid of disability, whatever form it took and however people responded to it. Later films would show Disney was willing to learn from Quasimodo as they had from Ariel, and keep trying to get inclusion right.

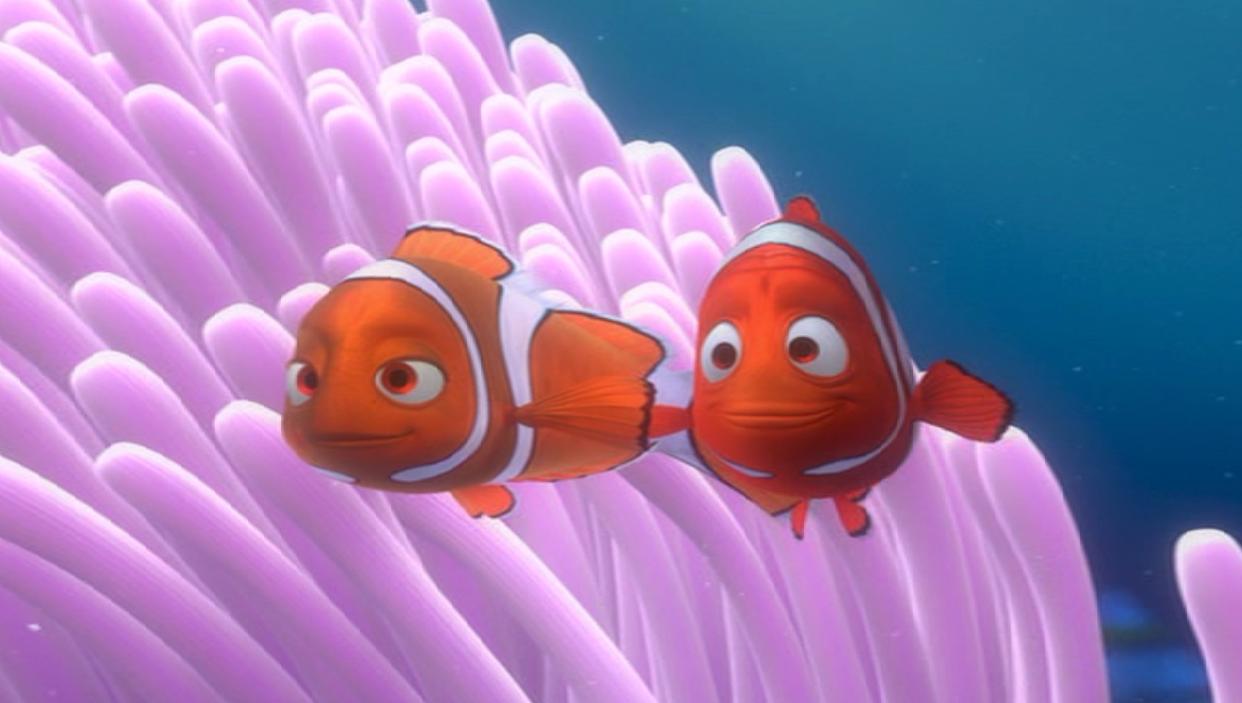

Nemo: Give Disability a Truly Big Story

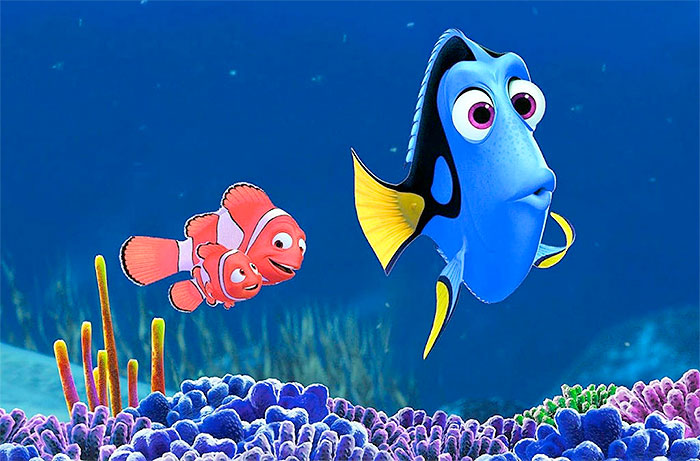

In 2003, Disney/Pixar gave viewers Finding Nemo. As with our previous two films, Finding Nemo was not necessarily meant as an attempt at inclusion or a disability story. Yet, it became the most inclusive story Disney had crafted to date, in that viewers of all ages adored, not just the underdog clownfish with the bad fin, but his story and its themes. And while such inclusion had happened with other Pixar films, the fact that Nemo and other characters have disabilities, turned Finding Nemo into a great disability inclusion story, too.

Like Quasimodo, Nemo is an innovator. He doesn’t have multiple disabilities. His only disability is a “bad” fin, presumably sustained in the barracuda attack that killed his mom and siblings. It’s not entirely clear why the fin is “bad,” but it looks a little torn or short, and it impedes Nemo’s swimming to varying degrees. Nemo then, is an innovator partly because his disability is visible, but not thoroughly explained through magic or misfortune. Nemo reads more like a character who works around disability without trying to explain or overcome it. He’s a lot like a child with a congenital disability who accepts, “I was born this way,” and therefore, compensates without thinking.

Nemo is an innovator because he is the first disabled Disney character whose disabilities truly affect and change other people. This is somewhat true for Quasimodo and Ariel; for good or ill, the people around them had to cope with some form of disability to become part of their lives. But Nemo’s disability is one result of a cataclysmic event that affected his entire family. It’s not the biggest result, either, as disability sometimes is for other characters. That honor goes to mother Coral’s death, the death of siblings, and father Marlin’s post-traumatic stress. In other words, Nemo’s disability is not a tragedy in itself. It doesn’t set him up to be a burden to others or ostracized. If anything, Nemo’s fin, and some other disabilities we’ll see, are catalysts for a bigger story.

Fully Human Disabled Characters

Nemo is a fish, but in many ways, a stand-in for a human child. He thinks and behaves the way a young child does. He’s naturally curious and eager to experience everything around him. He relates to the world in concrete terms, and while he understands actions and consequences, can’t make long-range connections between them yet. He loves his dad Marlin and wants to be good, but struggles with temptation and rebellion. In other words, fish or not, Nemo is a fully human character. He’s a hero worth rooting for, but he makes mistakes. He’s defiant and impulsive, and likely to panic when he realizes a problem is bigger than he thought. Nemo is every kid at one point or another, including kids with disabilities.

Nemo’s humanity is especially important for disabled viewers and their parents or guardians. In many stories inside and outside Disney, characters with disabilities are not allowed Nemo’s level of humanity or relatability. Instead, characters with disabilities are satellites to characters without them. They are victims, as Ariel and Quasimodo are, but may not be allowed to step out of that role. Some disabled characters are almost impossibly compassionate, forgiving, and self-sacrificing, while others use their disabilities as excuses to act rude, thoughtless, or sometimes evil. At times, creators try to capture disability’s reality by letting disabled characters acknowledge how hard life with a disability is–but never letting them move forward within that experience. Thus, the stories of these characters become lessons in how horrible ableism, and disability itself, can be.

Nemo’s bad fin does make his life difficult, but not in all the ways viewers might be used to. Nemo struggles less with his fin than how others react to it. For example, Nemo defies Marlin because the latter is overprotective. Any parent would be after the loss of a spouse and other children. But Marlin takes his anxiety to higher levels than a lot of parents would, including parents of disabled children. Marlin, for instance, lashes out at Nemo–“You think you can do these things but you just can’t!” Real-life parents of disabled kids might well think this, but few would say it in such a knee-jerk way. Similarly, real-life parents might caution a teacher about their child’s need for accommodations, as Marlin does for Mr. Ray. But most parents would not then hover around the classroom or caution their kids against doing commonplace “first day of school” things, like wandering away from the teacher’s watchful eye with new friends. Marlin does, and it sends Nemo a negative message. “Not only can’t you do things, but you shouldn’t. Unlike these other kids, your attempts at having normal experiences will get you hurt.” In response, Nemo struggles with fear, but ultimately becomes angry and openly defies Marlin, swimming too close to a passing boat on purpose. Real children, especially ones with disabilities, won’t get the idea that defiance is okay from this. However, they may well relate to the frustration of wanting to do something, only to struggle when other children don’t, or have their parents bar them from the experience when other kids get to have it.

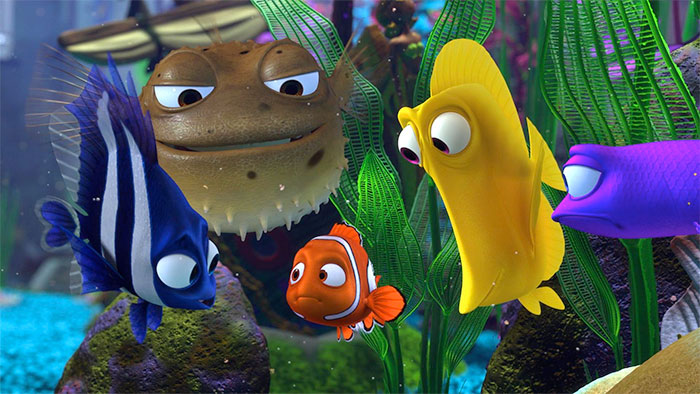

Nemo’s relatability within a disability context continues throughout his film. When he’s swept up into a scuba mask and taken to Sydney, Australia, he’s terrified. He regrets his impulsive actions and cries out for his dad, as a little kid might when they’ve either become separated from a parent or gotten themselves in a scary situation. But Nemo also experiences the wonder children do when they realize they’re in a new situation and perhaps, getting the opportunity for an adventure. He’s awed at the huge ocean beyond his safe little anemone, and frightened of Dr. P. Sherman’s fish tank. At the same time, Nemo is open to interactions with the “tank gang” and wants to understand their world. Telling his story lets Nemo relate to the other characters like Gill and Flo, and shows them they all have something vital in common–the desire for freedom. The “tank gang” is older than Nemo, and most of them speak and act more as adults than children. However, Nemo’s interactions with them are similar to the way children try to build common ground when looking for new friends.

Tackling the Constructs of What “Disabled” Means

After Nemo has been in the tank a short time, viewers get to see another way he relates to people with disabilities. Nemo gets stuck in the filtration system and panics because his bad fin makes it hard to get out. He immediately says he can’t do it, displaying learned helplessness, something many people with disabilities experience. Learned helplessness occurs when someone is consistently told or shown they are incapable of certain things, so they accept that as truth and stop trying. The message usually comes from someone like a loving parent or guardian, who means well but unconsciously believes the trope Disabled Means Helpless. Nemo is a prime example; his dad has taught him “can’t” and “won’t” and “shouldn’t,” so when faced with challenges, our young hero can only panic and yell for help. Nemo wants to break free of the construct, as we see from his willingness to get too close to Dr. Sherman’s boat and net in the first place. But without an alternative to learned helplessness, Nemo, and other people with disabilities, can’t see how breaking free will work.

Nemo’s alternative to learned helplessness comes from Gill, the stoic tank gang leader. When Nemo gets stuck, Gill orders him to get out of the filter. “I can’t, I have a bad fin,” Nemo wails. “Never stopped me,” Gill says while swimming away. Indeed, he has the same condition as Nemo, except his fin looks much more tattered and is possibly less functional. Gill’s reaction might seem cruel to viewers at first, especially adults who believe it is mean and discriminatory not to help disabled people, of all people, when they can. However, Gill’s intention isn’t cruel. Nor does he intend to deny Nemo’s disability exists or influences his life. Rather, Gill gives Nemo the one message he’s never gotten. “You can do the things you want to do. There are ways to accomplish what you need to, disability or not. Fixating on what you can’t do will make you stuck.”

Nemo gets the drift and moves from, “I can’t” to asking Gill how he can get out. Gill patiently teaches him to wiggle opposite fins until he can free himself, and praises Nemo for his success. Nemo’s willingness to try, overcome obstacles, and ally himself with the others also inspires Gill to initiate him as a formal tank gang member, during a ceremony at Mount Wannahockaloogie (the plastic summit in the tank). And when Nemo reveals a plan to get himself and the tank gang away from Dr. Sherman’s cute but bratty and inept fish-killing niece Darla for good, Gill listens. He agrees to the plan because he sees Nemo’s growth and change. Gill’s protege is becoming the intrepid, if not fearless, fish Gill knows he can be, and is gaining confidence in himself to become that fish as well.

Disabled Characters with Complete Journeys

With the help of a blocked filter, a filthy tank, some plastic bags, and a seagull named Nigel, Nemo and his new friends make it back to the ocean. Meanwhile, Marlin, who’s been searching for his son the whole time, reunites with him in the harbor outside Dr. Sherman’s office. At first, this seems like an unsatisfying end to Nemo’s journey. He’s back with his dad, and while he’s safe, viewers may well wonder if he will go back to a life of overprotected learned helplessness. After all, in too many stories, this kind of thing happens to other disabled characters. They leave safety and learn lessons–usually about how important they are because they can teach the able-bodied how to be “better” people–but then return, in one way or another, to the status quo. This type of arc happened for Ariel and Quasimodo, too; they got what they wanted, but each returned to the way things were in some approximation. Ariel lost her disability because it no longer served a purpose, while Quasimodo remained disabled and achieved acceptance, but also did not win Esmeralda’s heart and possibly did not spend a lot of time outside Notre Dame after his story.

With Nemo, a return to the status quo doesn’t happen. He does return to his anemone with Dad, and resumes life as a regular kid–er, fish–who is growing up but still needs care. And yes, Nemo still has his bad fin. What he doesn’t have is that sense of learned helplessness, or a desire to rebel to make himself understood. Nemo retains some of his caution, as does Marlin–they still double-check for danger before leaving the anemone, for instance. But at the end of the film, they do this only once, not multiple times. Nemo swims off to school on his own, with Dad urging him to stay safe but waving from a distance and trusting his son will be okay. Nemo’s teacher and friends greet him enthusiastically, implying acceptance and inclusion.

Nemo, then, becomes the first character with a disability in Disney to make a complete character journey. That journey lacks pitfalls such as the Throwing Off the Disability trope Ariel experienced. It also lacks “inspiration porn” messages, because Nemo is not brave or a hero just for going to school or showing his dad he can do normal things. Instead, Nemo, like so many abled characters, has had a legitimate chance to show courage. He has gone through legitimate growth and learned lessons other than “I’m not broken” and “My disability can’t stop me.” If anything, he has learned his bad fin may well get in the way sometimes, and that, coupled with his personality, means he may always be a little more careful than other fish. But Nemo’s big lesson is that he is part of communities–a small one within his family and school, and a bigger one within the ocean. Sometimes, his community will need him, or will invite him to explore, learn, and have adventures. When that happens, Nemo will be ready and capable. Like abled children, Nemo learns what it means to grow up, and he will be allowed to grow up like any other kid, including kids with disabilities.

Balancing Help and Autonomy

With Finding Nemo, Disney finally got a lot of facets of life with a disability correct. While not human, Nemo was the most relatable, adaptable, and fully realized character with a disability the company had created to date. However, telling any story well takes time, especially a story as big as “the disability story,” which is different for everyone and has so many facets.

One facet Disney could’ve spent more time on in Finding Nemo is the balance between help and autonomy. As noted, learned helplessness is a negative, yet all too common message people with disabilities receive. That message makes achieving autonomy and agency much harder than it usually is for abled people, and harder than it has to be for most disabled people. Too often, the time-honored message of what author Mary Johnson calls “help the handicapped” gets in the way. That is, people–and in this case, fish–are so used to helping disabled people, they assume any alternative is wrong, as with Gill’s initial interaction with Nemo.

“Help the handicapped” and learned helplessness, then, are not the right messages. But both disabled and abled people should be careful not to hold up autonomy as the “gold standard,” either. That is, people with disabilities want, need, and deserve to be independent, but if independence is pushed too hard, the implication becomes, “Asking for help is never okay.” In many cases, this translates into ableism. Abled people assume, “If [person] were really disabled, I could see it and help,” or “If [person] struggles so much, why are they in this arena?” It can also translate into internalized ableism for disabled people, because they assume blame if their disability gets in the way of what they want, or leads to misunderstandings.

Additionally, failure to balance help and autonomy reinforces the idea that independence is the ultimate goal for all people. Indeed, most people with disabilities are pressured with messages of independence from day one. This writer attended physical and occupational therapy for 12 years in the name of “learning to be independent.” She has interacted with people who did not understand her encounters with ableism in the workplace and questioned her capability to be financially independent. Consciously or not she, like many others, was presented with independence as a zero-sum game. In other words, for disabled people, the choice is independence as defined by a majority-abled society, or total dependence, either on family members or services and institutions.

Too often, the middle ground of interdependence is not presented, either in real life or fiction. Finding Nemo touches on interdependence a little, in that the tank gang has to depend on each other, including Nemo, to get out. But at the end of the movie, because of his youth, Nemo goes back to his safe, ordered life. It’s assumed he’s learned enough to keep growing and become independent one day, but because he mainly interacts with Dad and Mr. Ray, we don’t know how interdependent Nemo will be. We also don’t see him asking for help, or balancing his disability with strengths, like skills he learned while in the tank. Again, autonomy is privileged, and help, while not stigmatized, is connected to who Nemo “used to be”–as in, helpless and a little whiny. A more balanced approach, something as simple as Nemo dealing with his fin while maintaining reliance on strengths, would’ve gone a long way toward striking a balance.

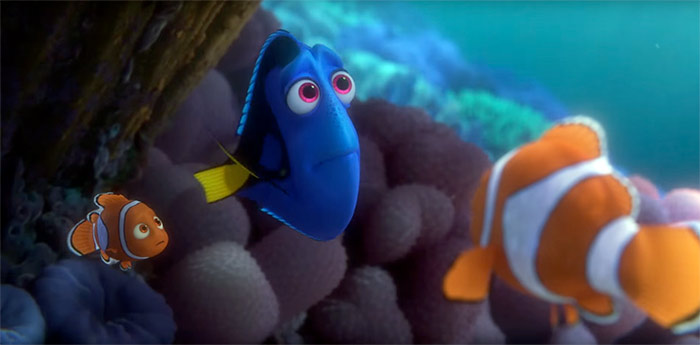

Presenting Disability as Multi-Dimensional

In addition, Finding Nemo might’ve had stronger representation if Disney had presented disability as multi-dimensional. In other words, Finding Nemo presents viewers mainly with one disability and one character’s journey. In many ways, this is okay. Nemo is our protagonist, and his journey is complex enough that much more would become too hard to follow. Plus, we have Marlin as a deuterotagonist, experiencing a parent’s version of a “hero’s journey,” which gives Nemo’s story even more depth. Within that journey, viewers meet Dory, a blue tang whose short-term memory loss stands in for a memory or amnesia disorder. Some viewers read her as having a mild cognitive disability as well, or perhaps a traumatic injury or mental illness. Nemo and Dory then, do show viewers two types of disability, and the complexities of each. However, the two aren’t together for most of the film, so when we see them, they’re only relating to non-disabled characters. To Disney’s credit, this never reads as Dory or Nemo “educating” the ignorant, abled fish about their disabilities, or “why we’re more alike than different.” The implications though, are not always good.

Dory is the best example of this slip-up. She’s the comic relief, as befits a character played by Ellen DeGeneres. And it’s great that she can laugh at her condition and eventually invite others to laugh with her. However, viewers are more apt to laugh at Dory’s memory loss, especially when it’s played up alongside stuff like her claims to speak whale or her enunciation of “escape” as “Es-cah-pay.” Fans who otherwise love Finding Nemo have pointed out that this can be read as poking fun at the cognitively disabled or memory-impaired. In addition, presenting Dory as a funny, sweet, and childlike character may reinforce the tendency of abled people to infantilize disabled counterparts, especially those who are cognitively disabled and already labeled with concepts like “mental age.”

Nemo falls prey to one-dimensionality too, but in a different and almost opposite way. That is, his disability is so mild, viewers might never know about it if it wasn’t explicitly mentioned. With a few notable exceptions, his fin doesn’t affect Nemo much. Again, it can work in his favor. As noted, it gives him credibility as a congenitally affected character who knows nothing different. But the way Nemo’s disability pops in and out of the story sends the message, “The milder the better.” In other words, Nemo is worthy to be his story’s hero–while someone like Dory is a secondary character–because of how “normal” he is otherwise. Nemo can blend in where characters like Dory can’t, which is unfortunately more “palatable” for abled viewers. Even Gill, whose disability is more “severe” than Nemo’s, spends much of the movie in the controlled environment of his tank. Thus, the message becomes, “Disabled people are okay, even good. If they can be ‘normal,’ great, but otherwise, they’re better with their own kind.” Again, no ableism is consciously meant. But the fact that “higher-functioning” characters get most of the attention and growth, when other characters and disabilities exist, is a red flag.

Vanellope: Show Disabilities as Part of the World

After Finding Nemo, it seemed characters with disabilities had vanished from the Disney landscape. It would be almost ten years before Disney gave us another CWD, and she would be secondary. Yet Vanellope Von Schweetz, deuterotagonist of 2012’s Wreck-It Ralph, is a great example of how far Disney has come on its disability inclusion journey. Like other characters before her, she has unique lessons to teach, and her story has a great mix of positives and negatives from which real people can learn.

Vanellope might look like a cop-out at first. She’s never called disabled, nor does she have a classical disability like Ariel’s muteness or Quasimodo and Nemo’s physical issues. Thus, she’s “coded” disabled more than accepted as a full representation. Coupled with Vanellope’s female status, one could easily conclude Disney is still reluctant to let a female character be “truly” disabled, which would be both ableist and anti-feminist.

As with our other characters, there are imperfections in Vanellope’s representation. In her case though, coding rather than outright representation works in her favor on many levels. Coding may actually make her more accessible to the disability community. As for the abled community, Vanellope is accessible to them too, but her particular coding and character may make her less likely to be taken over by the abled community, as happened with our last female disabled character, Ariel. (Recall, because of the nature of her muteness, Ariel is still considered abled, a character who belongs to or with the majority). Therefore, Vanellope may be one of the best characters for both communities to turn to when considering representation.

Disability in Alternate Universes

Vanellope is a human character, but she doesn’t live in our world. Like a lot of Disney and Pixar characters, she shares her world with human-like characters and non-humans with varying degrees of sentience. Vanellope thinks, speaks, and acts as a human, but lives with rules and constructs unfamiliar to the human universe. In other words, Vanellope and others probably know the concept of disability, something that affects your abilities and may make you weaker or stronger than usual in certain ways. But characters in Vanellope’s world don’t use the terms “disability,” “handicap,” or “impairment” because they don’t have a real frame of reference for it. Disability exists only insofar as it makes sense in their universe.

Vanellope and her fellow characters live in a video game world, specifically Litwak’s Arcade and more specifically, Sugar Rush, a “candy go-kart game” similar to Mario Kart. Video game characters can die in their games, or die permanently if they’re outside their own games because the lack of “lives” means they can’t regenerate. But video game characters can’t be disabled unless their programs specifically say they are, and in the arcade and Sugar Rush, no programs do. The closest thing this world knows to disability is “glitching.” Vanellope has a glitch that causes her to blur in and out of focus, especially when under stress. It’s not named, although she calls it “pixlexsia.” In our world, the glitch is probably best compared to a complex physical disability like cerebral palsy, or a disability with physical and emotional components like anxiety or post-traumatic stress. Again though, without a name, the glitch can’t be compared to human disabilities in a 1:1 relationship.

This is not a negative, however. If anything, Vanellope’s particular glitch works in her favor. It sends the message that disability can and does exist outside of contemporary, human-centric settings, such as those revolving around fantasy, science fiction, or technology. Too often, disability is left out of these settings because authors and readers assume they would naturally not exist. Magic or technology would have eradicated disability, the common rationale goes. In harsher settings, such as those found in some sci-fi and dystopia, the rationale goes further, stating people with disabilities would’ve been wiped out because they couldn’t possibly survive. Real readers and viewers with disabilities dislike and argue against this rationale, and while the landscape of disability outside contemporary settings is improving, the change is slow. Therefore, Vanellope and her glitch are a welcome change, and her world a refuge. This is especially true for PWDs who love the genres mentioned or who identify as “gamers,” “geeks,” or members of similar subcultures.

Additionally, Vanellope’s glitch works in her favor because of the kind of mini-world she inhabits inside the video game universe. That mini-world has a lot of flaws, which we will see shortly. But it is a bright, seemingly joyous world of candy and fun, not a dystopian wasteland. Sugar Rush engages. It entices. It invites viewers to come in and enjoy, even if they can tell something, or perhaps many somethings, are not right. The fact that disability exists in this world sends the message that being disabled doesn’t mean one is relegated to depths and darkness. The fact that Vanellope lives and thrives in this world, as hard as that can be, instead of being eradicated, indicates Sugar Rush has room for inclusion. And the fact that Vanellope has a smart, sassy, and engaging personality indicates that she is what people with disabilities are like. They may well struggle or get treated like outcasts, but they don’t have to function as victims, as characters in earlier Disney films did. Instead, Vanellope shows characters with disabilities can fit into any world. Depending on how hospitable that world is, fitting in could mean slipping easily into a place made for you–or it could mean making your own.

Disability as Inspiration Minus the Porn

Vanellope is an inspirational character, and the first disabled Disney character who specifically eschews inspiration porn. Inspiration porn is the objectification of people with disabilities, for the purpose of making abled people feel good or teaching them to be kind, loving, or tolerant. Ariel, Quasimodo, and Nemo don’t fall into inspiration porn on purpose, but they can easily be read as porn objects because of their circumstances. Their films tend to focus on the fact that these characters are alone in their worlds, disabled, and therefore disadvantaged. Additionally, their films tend to play up these characters’ need for help and sympathy. This happens partially because Ariel, Quasimodo, and Nemo are typical sweet, somewhat innocent, Disney characters.

Vanellope’s circumstances and personality make her less likely to get objectified. Like our other three characters, she is either alone in her world or treated as an outcast. In Vanellope’s case though, isolation is somewhat by choice. Isolation also shows off her ingenuity and determination. When she wasn’t welcomed in the main part of Sugar Rush, Vanellope created her own home in an unfinished bonus level. She communicated, “I decide where I belong.” One could argue she had no choice; as she later explains to Ralph, “Glitches can’t leave their games.” The fact remains though, Vanellope had the gumption and independence to make Sugar Rush as much home as possible. Independence was not forced on her because of her glitch. Nor is it something she worked toward as an ultimate goal, the way most disabled people are told to do. Rather, Vanellope’s independence is a natural part of her. Her determination is the same way. That is, many people with disabilities are praised for being “determined to do” normal things like go to school, participate in activities, or even care for themselves. Vanellope is indeed determined to make Sugar Rush her home, but not many kids, disabled or not, would approach that goal by building the home from scratch. Vanellope knows determination is not enough. When Ralph accuses her of thinking she can “just magically win the race ’cause [you] really want to,” she fires back that no, she knows she can win because she’s already “a real racer.” Vanellope might be tiny, cute, and the perfect conduit of inspiration porn, but darned if she’ll let anyone think of her as helpless, or special for doing anything less than her best.

Additionally, Vanellope avoids becoming objectified because of how she presents herself. From the moment she’s onscreen, Vanellope is sassy, snarky, and one of Disney’s most quick-witted characters. Some of this can be attributed to her voice actress, comedienne Sarah Silverman. But Vanellope could just as easily have been a sweet “Princess Classic,” the trope name used to describe less self-determined predecessors like Snow White or Aurora. Vanellope would have good reasons to fall into that mold, too. Disabled or not, she’s prepubescent and living in a universe that literally runs on sugar.

Instead, Vanellope bucks every princess trope and expectation viewers could throw at her. She wears a skirt reminiscent of a Reese’s Cup lining, over turquoise-striped sweatpants and a hoodie. Her hair is messy and covered in sprinkles and candies, not styled in perfect waves. She doesn’t talk to animals or sing (her solo in Ralph Breaks the Internet is a parody). And Vanellope is not unfailingly generous, retiring, or kind. She shows affection mostly through insults, especially with Ralph; the cookie medal she makes him is inscribed, “To Stinkbrain.” She knows the downsides of her situation and accepts them, telling Ralph, “Isn’t this neat? I sleep in these candy wrappers. I like, bundle myself like a little homeless lady.” Should you insult or perhaps betray her, Vanellope will react like any kid and cry or sulk. Later though, she will come back and call you out on your actions, usually with a sarcastic “Shame on you” or a name like “selfish diaper baby.”

This isn’t to say disabled characters are inspiration porn unless they’re sarcastic and nasty. It’s also not to say any kid should be sarcastic just for the fun of it. However, Vanellope’s personality is unique to disabled characters in particular, who are too often painted as 100% good, 100% evil, or unable to function. It’s also unique to Disney characters in general, especially the females. Considering Vanellope is an honorary princess, she stands out all the more. She communicates to both abled and disabled viewers that being a nice person can be compatible with standing up for yourself. It’s compatible with being brutally honest about a bad situation, or using humor, insults, or gross frankness when appropriate. Additionally, Vanellope offers people with disabilities some agency over inspiration. That is, PWDs may not be able to stop others from thinking of them as inspirational, or trying to use that negatively. But if disabled people are allowed agency, allowed to craft their own identities, they can then take charge of when and how to use inspiration.

Disabled Characters Taking Charge

Vanellope von Schweetz stands out among other disabled characters because she takes charge. Well before she knows she’s a princess, she does everything in her power to enter and win a Sugar Rush race. She uses every strength at her disposal, from her aforementioned wit to her climbing and foot-racing skills. Later, she collaborates with Ralph, but there’s something important about that collaboration. Vanellope initiates it. She persuades Ralph to help her through mutual benefit; helping her win a race means he’ll get back the hero’s medal he needs to become a good guy.

As the film goes on, Vanellope remains the decision-maker, the planner, and the expert. She knows every inch of Sugar Rush, including the areas she isn’t supposed to access, and uses the knowledge to her advantage, telling Ralph where to go when they need to escape King Candy’s guards. Vanellope later warns Ralph about obstacles like falling Mentos and boiling diet cola–obstacles both characters later use to save Sugar Rush. Vanellope also takes charge of procuring her kart, sneaking Ralph into the bakery and guiding him through the designing mini-game. As for Vanellope’s race prep, Ralph does teach her to drive the kart. Once she has the basics though, Vanellope jumps into driving fearlessly, to the point of “almost [blowing] up the whole mountain.” But as noted, Vanellope’s recklessness does lead to triumph in the climax.

Vanellope’s role in her partnership is a huge positive message for viewers with disabilities, and one they don’t often receive. As advocates like John O’Brien explain, PWDs are usually looked at with a “deficit mindset.” 2 Their diagnoses encompass their entire identities, or are reduced to demeaning monikers like “special needs.” Thus, the abled people meant to help them through measures like Individualized Education Plans (IEPs), therapies, or goal-setting deny them agency. This is usually not malevolently meant. However, the deficit mindset does contribute to learned helplessness and poor self-concept. As advocate Kathie Snow writes in her allegory “Annie in Disability-Land,” this happens so often that when disabled people are asked what they want to do, they don’t know what to say. 3 Abled people around them take silence for ignorance, and continue to make plans for them based on deficits or their “expert” disability knowledge.

Vanellope, more than any other disabled Disney denizen, throws the deficit mindset out the window. In fact, she never heard of it. She’s aware she’s a “glitch” and an outcast, but if you ask her, the people who malign her are the ignorant, deficit-driven ones. “I’m a racer! It’s in my code,” is not some inspiration porn wish. It is her creed, her driving force, her identity. She will not stop until she finds someone who believes in her and will help her the way she wants to be helped. Ralph fulfills that need, unlikely ally though he may be.

If anything, viewers might read Ralph as “disabled” too, if they subscribe to the social model of disability. Unlike the medical model, which says disability is a problem to be fixed or cured, and that barriers are the disabled person’s fault, the social model says the opposite. The social model says PWDs are only “disabled” insofar as barriers force them to be. If barriers, physical and otherwise, are removed, a disabled person should get to function on a completely level playing field, because they will get the accommodations they need without pushback. Ralph then, and even Vanellope, don’t fit the social model if we try to label them with classic disabilities (limb differences, cerebral palsy, learning differences, deaf/blindness, etc). But both Ralph and Vanellope are “disabled” by their environments, and by people who approach them with deficit mindsets. Thus, Vanellope’s choice in particular to partner with Ralph shows she can empathize with others, no matter how like her or unlike her they may be. That choice shows she recognizes outcast status does not have to make anyone a victim, and that she is self-determined enough to help others change their futures. Vanellope steers her own ship–er, kart–and if others happen to be inspired or their hearts happen to be warmed, that’s just icing on a cake refreshingly lacking in sugar.

Disabled Characters with “Superpowers”

In Wreck-It Ralph and Vanellope von Schweetz, did Disney give viewers a perfect representation of disability? Vanellope’s representation certainly may be the best we’ve discussed so far. But just as Vanellope is human and flawed, so is her representation.

One interesting flaw in Vanellope’s character is the eventual handling of her glitch. As noted, it’s treated as a disability. Disney almost veers into the trap of treating disability as disease too, because as King Candy explains, Vanellope’s glitching could put Sugar Rush out of order. Because glitches can’t leave their games, if Sugar Rush’s plug is pulled, Vanellope would die, permanently. However, it turns out King Candy lied. Actually, Sugar Rush resets when Vanellope crosses the finish line in the climactic race. As a result, she’s revealed as the game’s “rightful ruler” and princess, and her glitch is read as a superpower. “I was here, I was there, I was glitchin’ through the walls,” she boasts. And indeed, she becomes the game’s most popular avatar, because random glitching guarantees her player a win. Vanellope is not only a royal, but a superhero. Add in her disability-turned-gift and cool personality, and she could seem too good to be true.

Therein lies the problem, for Vanellope and other characters with disabilities. Sometimes, a Disney or other CWD will have abilities written as compensation for the disability. Or, the disability will be written so that its presence helps a CWD do something he or she couldn’t otherwise do. This can be as obvious and fantastical as Vanellope’s glitch power, or it can be more down to earth. For instance, a wheelchair user or blind character who is also intellectually gifted is usually assumed to be a genius. A character with a learning disability might also be a great artist or superstar athlete.

On the surface, there is actually nothing wrong with the Disability Superpower trope, for a lot of reasons. It can happen in real life to a point; students who are disabled but also gifted, like this writer, are called “twice-exceptional” or 2E students in many schools, and are given services to meet both exceptional circumstances. And although autistics don’t like the savant stereotype, real savants do exist. Besides that, a disability can sometimes make a hero or heroine more admirable because it means they’ve had to hone other skills to expert level. This is a situation TV Tropes calls Handicapped Badass. It occurs when a disabled character protects others through brawn or brain in ways most abled people don’t, but is not necessarily “superpowered.” A Handicapped Badass might be a pirate like Captain Hook or Once Upon a Time‘s Killian Jones, a mentor and professor like X-Men‘s Charles Xavier, or a veteran with a combat injury, who still protects his family, friends, or proteges, like Alastor “Mad-Eye” Moody in the Harry Potter franchise. Their handicap might not be central to the plot, but they may have moments wherein the audience is reminded how it makes them more awesome than usual. King Fergus from Brave, for instance, fights the bear Mor’du and punches him in the face despite losing a leg to the same bear years before.

The question then, becomes how to create a character with a disability who, unlike Vanellope, is not “superpowered,” or whose gifts do not come off as compensation. This may be the finest line disability representation has to walk (or roll). That’s probably why Disney and other franchises haven’t gotten it exactly right, depending on who you ask. Yet there are ways around disability or extraordinarily gifted, wherein the former condition has to “disappear.” You can have both, and achieving both often involves avoiding some of the other flaws in Vanellope’s representation.

Promotion to Princess–And Abled?

One major problem with Vanellope, and what makes the disability superpower issue worse, is her promotion to princess. Vanellope herself doesn’t like the title; once the game clothes her in pink and sparkles, she almost immediately ditches them for her regular clothes. She also says she’d rather be “President Vanellope von Schweetz,” head of a “Constitutional democracy.” That’s great, but it feels like a cop-out Vanellope’s writers threw in so they wouldn’t be accused of falling back on the princess formula. Worse, it reads like an erasure of Vanellope’s whole character. Most notably, Vanellope makes a distinction between being a princess and “a racer with the greatest superpower ever,” as if she cannot be both. This unintentionally sends the message if you’re going to be a princess, whatever that means, it’s your major identity. Everything else comes secondary to the crown.

In terms of disability representation, the princess identity erases that for Vanellope, too. Her glitch has already been upgraded to superpower, which isn’t necessarily problematic but was oddly handled. Add in the princess title, and it feels like Vanellope has also been promoted to abled. After all, who would dare suggest a princess had less than perfect abilities? Not Sugar Rush, as the denizens prove (Taffyta falls into hysterics when Vanellope jokes about her tormentors being executed). More disturbingly, not Disney, either. Until Vanellope, Disney hadn’t had a disabled princess since Ariel–and remember, her muteness “doesn’t count.” Because Vanellope is more coded disabled than actually called so, and because of her promotions, she’s not really a disabled princess, either. As noted, her coding makes her a lot more accessible. But her new title sounds a lot like Disney saying, “We’ll allow disabilities, but not for a princess.” Princesses, whether they’re actual or honorary like Vanellope, have an image to maintain. A glitch, a wheelchair, blind eyes, or braces would taint the line.

As noted, Disney tries to cover up this mistake by having Vanellope eschew the title and say she’d rather be President. Yet this is a feeble attempt. It’s almost a joke, considering Vanellope’s world means she shouldn’t know what a president is, let alone what a Constitutional democracy is. Disney would have done better to drop the princess issue altogether. They could have gone the full superhero route, having Vanellope battle King Candy straight up, on and off the racetrack, or having her battle him with Ralph as a team. Another possibility involves rewriting the script so that, while King Candy retains his royal title, his abuse of it means that once Vanellope resets the game, all trappings of royalty disappear for everyone. Still another possibility involves Sugar Rush never having any royal connections, and King Candy being presented as a dictator who abuses everyone, but is accepted because that abuse is “sugar-coated” in gaslighting and protection from glitches like Vanellope.

There is an argument against all these possibilities. Disney has become a princess-based empire, for better or worse. Plus, one could make the argument that in not making Vanellope a princess, Disney would bar her from the highest honor a female character can get, possibly with ableist motives. Therefore, Vanellope becomes unique in yet another way. More than the other disabled characters we’ve discussed, she encapsulates the successes and pitfalls of disabled representation as we know it now. She’s a reminder that all representations have room to grow. As long as we do our best, with positive motives, we can expect growth to happen and representation to trend in a good direction.

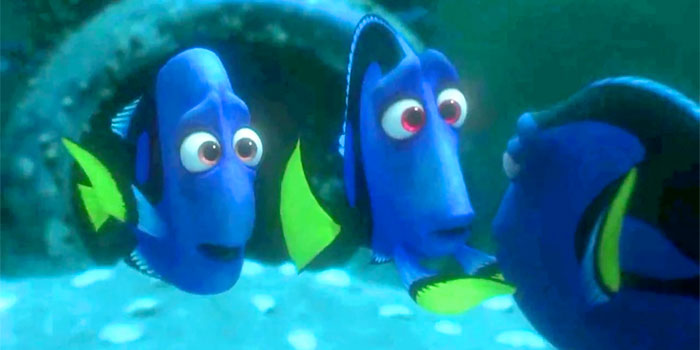

Dory: Let All Disabled People Tell Their Stories

Disney’s disability representation has trended in a good direction since Vanellope. Its most recent example is its best example of representation yet. In 2016, Disney/Pixar gave viewers Finding Dory. The film reunited us with our favorite blue tang, as well as her short-term memory loss. The film gave Dory her own story and told that story well. In addition, it placed Dory, and disabled characters, in the wider world of disability itself.

According to national news source Disability Scoop, the CDC, and other authoritative sources, about 15% of the U.S. population lives with a disability. That doesn’t even take into account the billions of people living with disabilities worldwide. This information, plus the recent movement #Wethe15, reminds us people with disabilities are a people group in and of themselves. Yes, they have individual stories, and those deserve to be told. Yes, they can and should interact with abled people and be represented fairly while doing so. Yet like any other people group and culture, disabled people need wider identities and stories.

Dory gives disabled people those wider stories. Of course, characters with disabilities have had big stories before, as we saw with Nemo. They have had major impacts on their worlds and fellow people, as we saw with Vanellope and Quasimodo. But Finding Dory takes all these elements and connects them to disability as an identity, a culture, and a state of being. More than other disabled Disney characters, Dory gives viewers a glimpse of what it means to embrace disability pride.

Disabled People as Individuals and Group Members

In most stories starring a disabled character, the protagonist struggles at least a little with his or her unique situation. The character is probably the only disabled person in his or her “group,” whether that’s family, classes, the workplace, or the story’s universe. If the character knows other disabled people or creatures, they’re probably in a “special, disabled only” group, such as a disabled-only sports team at a rec center or a special education class at school. The character may be told, “There are millions of others like you” or “You’re not the only one.” But the story itself makes these statements untrue. The character may come back with, “If that’s true, why haven’t I met any?”

Dory’s experience is the exact opposite. Like many disabled characters, she does struggle within the wider, majority-abled world. After she loses her parents Jenny and Charlie, she tries to get other fish to listen to her story and help her the way she needs to be helped. Most of those efforts don’t succeed, until she meets Destiny, Hank, and Bailey. All three of these characters have some form of disability. However, they are not segregated as people with disabilities often are. They may be quarantined because they are mistaken for ill, but their disabilities are not placed on a par with illness. Instead, they function in the wider world of the Marine Life Institute and are equipped to help Dory on her journey.

What’s interesting about Dory’s compatriots though, is how they fit into her journey. Finding Dory could’ve easily read as a journey of “proving our abilities” or “all finding ability together,” a la The Wizard of Oz. Instead, Dory’s disabilities and abilities, and those of her friends, only come up when they contribute to the bigger story of Dory finding her parents. For instance, Dory is thrilled to meet Destiny, a legally blind whale shark with whom she can speak whale and strike up a friendship. But it also turns out Destiny and Dory were “pipe pals” when they were little. Dory knows this information, but can’t access it until it’s truly important. Additionally, Destiny–and her poor eyesight–don’t play a role in Dory’s journey until this information is accessed and Destiny is needed. In other words, Destiny’s disability is not the only characteristic that makes her necessary.