How Princesses of Color Have Improved the Disney Princess Narrative

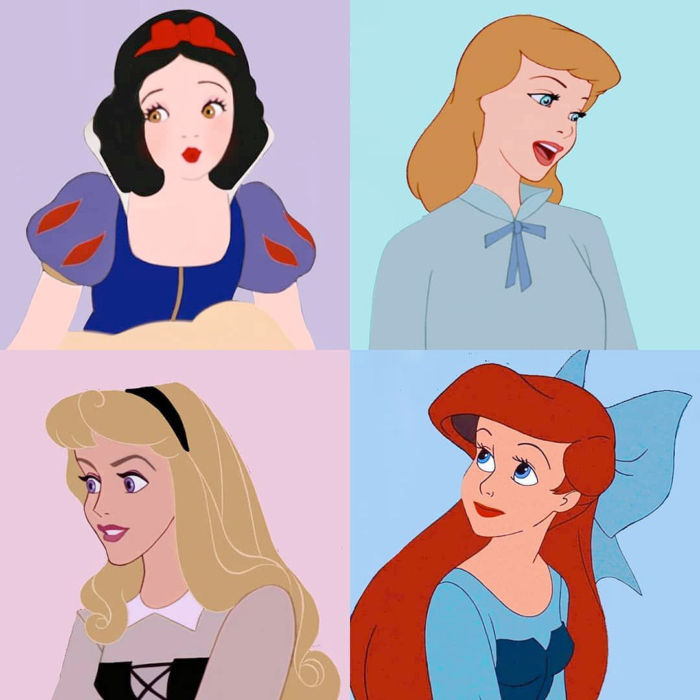

When most of us hear the term “princess,” a certain image comes to mind. Most of that image has to do with a personality archetype. We picture a “princess” as a fairy tale paragon–sweet, possibly a great singer, and often able to speak fluently with animals. Some of that image is also physical. The Princess Classic archetype, as she’s called in TV Tropes, is usually Caucasian.

This archetype is as old as, perhaps older than, the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, writers of some of our original and most beloved princess tales. Of course, these authors were from European countries (Germany and Denmark, respectively), so for them, the ideal woman probably was a white, blue-eyed blonde. However, this image of the Princess Classic carried on for centuries after the deaths of Andersen and the Grimms, even into the United States. Perhaps the best examples can be found among early Disney princesses.

The star of Disney’s first animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, is a brown-eyed, raven-haired beauty–but her skin is, as fitting, “white as snow.” The next two Disney princesses, Cinderella and Aurora/Briar Rose from Sleeping Beauty, are both blue-eyed and blonde. Snow, Aurora, and Cinderella also have personality traits in common, such as unfailing sweetness and submissiveness, varying degrees of skill in house chores, and the desire to fall in love. These traits may not resonate with modern women because they have endless skill-building and career opportunities available to them.

As decades progressed and values changed, so did Disney’s portrayal of the princess, in looks and personality. Ariel, for instance, is still blue-eyed, but the epitome of what TV Tropes calls the Fiery Redhead. Belle is a hazel-eyed brunette who loves books, apparently more than she loves people (her father excluded). The princesses’ motivations underwent some welcome changes, too. For instance, Ariel does fall in love with Prince Eric, though most people might call it “falling in lust” since they never had a conversation or meaningful interactions before then. However, close analysis shows Ariel was always more interested in getting to know the human world and becoming a human herself. Prince Eric happened to be a convenient conduit. Belle, too, does not start out longing for a prince. She wants “adventure in the great wide somewhere,” but not only for adventure’s sake. She wants to be understood, liked and accepted for who she is, and if we go by her reaction to Gaston, perhaps have the freedom to choose a path that doesn’t include traditional feminine roles.

Some of today’s analysts even argue that the original three princesses, Snow, Aurora, and Cinderella, didn’t want a prince and a royal lifestyle so much as they wanted dreams to come true. Still, a lot of those dreams, for the original trio and Ariel and Belle, ultimately end up involving men and royalty. Their motivations, at their core, stay the same. Perhaps in keeping with this, so do their appearances. That is, these princesses are all still white.

Of course, there is nothing inherently wrong with being a white princess. These young women didn’t choose their skin color any more than real people do. Race is not so much an issue as race in the context of motivation. That is, Disney’s white princesses generally have small-scale motivations that turn on bettering their personal lives and lifestyles in some way, which generally involves marriage and taking on at least some traditional feminine pursuits. For girls of color who may watch early Disney movies, this may not inspire a lot of resonance. Modern girls of color have probably experienced different barriers than their Caucasian counterparts have, even if they can identify on some level with Caucasian characters. For instance, a girl of color could identify with Belle because she and Belle are voracious readers. But Belle is not a woman of color; she is a Caucasian brunette. She may have faced obstacles to her education, but they were probably different from the barriers girls of color grew up with. For example, educated women of color may have faced language barriers or backlash based on race or nationality. They may have faced colorism, or the belief that light skin is “better” and more “privileged” than dark. The 2017 documentary Light Girls covers some real-life stories regarding these struggles. Real women tell of how they, their mothers, and grandmothers were often barred from schools, churches, and social gatherings based on colorism. In much of the United States, racism and colorism have been so prevalent that girls of color sought to pass for white or bleach their skin to take advantage of more opportunities.

Fortunately however, Disney has given us several princesses, and even an honorary princess or two, of color in recent decades. When we look at these princesses’ character formations, arcs, and motives, we find they are much “bigger” than those of white princesses. We find these princesses might be more realistic role models for white and non-white girls alike, and that they are huge helps in pushing Disney toward a twenty-first century understanding of what it means to be a woman of any race and relate to people across cultures.

For the purpose of our discussion, we’ll be using the term and abbreviation princesses of color or POC (POCs). “Princess of color” refers to a non-white princess with non-European heritage.

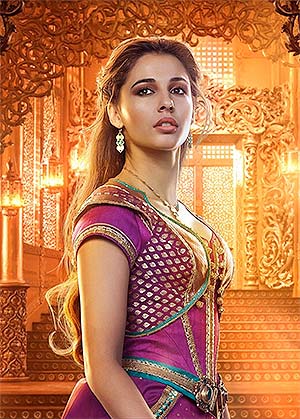

Jasmine, Aladdin: The People’s Princess

Jasmine was Disney’s first princess of color, from the fictional Arabian city Agrabah. Color and heritage aside, she might seem out of place in our discussion. After all, Jasmine is secondary to our titular protagonist Aladdin. She wears a turquoise top and harem pants outfit rather than a flowing gown, and while she loves her pet tiger Rajah, she doesn’t talk to him, nor does he talk back. But at first glance, she is a traditional princess with traditional expectations thrust on her, namely marriage. She does say if she marries she wants it to be for love, but doesn’t discount the idea entirely. So then, why would we begin with Jasmine, other than that her film came out first (1992), and she is a POC?

A few reasons exist for starting with Jasmine. To begin with, she is the first princess in the Disney canon to voice, “Then maybe I don’t want to be a princess anymore!” Whether or not they were born into royalty, none of the princesses that came before Jasmine ever turned the identity down–and pretty flat, at that. In voicing opposition, Jasmine starts a unique journey to self-determination. She doesn’t want to be a princess, but unlike Ariel or Belle or Cinderella, she doesn’t want to be a whole other person, either. She doesn’t only seek acceptance, though it would help her to feel understood. Jasmine wants to discover who she is outside the context of who she’s been told she is and raised to become. In that way, she’s a kindred spirit to historical women of color who may have been taught they belonged in secondary roles.

Jasmine disguises herself and goes unaccompanied into the marketplace, intending never to return to the palace, partially because of forced marriage but perhaps mostly because she wants to shed the “princess” label for good. She goes back willingly with a palace guard later, so the casual viewer might say Jasmine simply had a rebellious teenage “experiment” that failed. However, those casual viewers should look closer.

During her brief time in the marketplace, Jasmine absorbs a lot of information that will help her form an identity of her choosing, and actually help her should she stay in the princess role. Remember, a princess is a monarch who carries the responsibility of her people. Thus, when Jasmine sees a hungry little boy in the marketplace and tries to give him an apple, she recognizes for the first time that other realities than her own exist. This gets cemented when she meets Aladdin, who’s living on the streets, and learns that while his lifestyle has advantages, “scraping for food and ducking the guards” is a daily, inescapable reality. In fact, Jasmine quickly realizes there are plenty of tough realities outside the palace. She almost gets a permanent taste of this when the apple cart owner tries to cut off her hand for stealing. One could say Aladdin’s rescue of Jasmine proves she’s still naive and helpless, but as she says later, “I’m a fast learner.” Indeed, she is–so much that she stands up for “the boy in the marketplace” and grieves him when she hears he’s been executed. “I didn’t even know his name,” she laments to Rajah–showing she cares deeply for this “street” stranger she just met, and is already growing. That is, before, Jasmine might not have cared that a random poor boy was in trouble. The fact that she does, and took time to form a relationship with him across class barriers, shows she is becoming ready to relate to Agrabah as a nation of people. Moreover, she is becoming Disney’s first example of a princess who realizes her actions can and will impact more than herself and her immediate family or staff.

Jasmine continues this trajectory in a unique sphere, how she interacts with her story’s villain. She finds Jafar loathsome and at one point exclaims, “When I am queen, I will have the power to get rid of you!” Then again, this isn’t the first time we’ve seen a Disney princess mouth off to a villain. Ariel called Ursula a monster, and Belle added to the sentiment with Gaston–“[The Beast] is no monster, you are!” Jasmine takes it further than mouthing off. She proves herself an active obstacle to Jafar at least twice. Once, she blocks the hypnotizing powers of Jafar’s snake staff in an effort to snap her father out of them. Later, she becomes a linchpin in the overall plan to defeat the sorcerer, using a slinky (for Disney) scarlet outfit and feminine flirtations as distractions.

Some women and girls, particularly of color, might not like Jasmine’s methods of distracting Jafar, and they’d be justified. On the surface, they look like a negative, sexualized message. Historically and in the present, they may hearken back to atrocities committed against women of color (rape of slave women, slaves taken as mistresses, high numbers of trafficked women of color, and so on). Recall though that Jasmine loathes not only Jafar but feminine wiles for their own sake. She had plenty of opportunity to charm suitors before and didn’t take it. The more ostentatious and “attractive” a suitor is, the more she actively loathes him, and this includes Jafar. Also, she is the first princess to step in and directly confront a villain–a male sorcerer, no less. More to the point, she uses the seduction method because she has had time to analyze Jafar. She knows he’ll respond to this, and is in fact so caught up in lust he’ll drop his guard. Brute force won’t work; Aladdin tried that and almost died. Magic won’t work because Jafar is already a sorcerer and has used a stolen genie wish to become all-powerful. But Jasmine knows under the power, Jafar is still human and fallible. At the climactic point, she doesn’t care who Jafar is or what he can do. In her eyes, they are equals, and she’s going to meet him on equal footing. For Jasmine, the issue isn’t, this sorcerer has threatened her kingdom or the man she loves. The issue is, this is an evil person who has enough ego and power to hurt her entire kingdom on a permanent scale. She’s not going to stand for it. If Jafar wins, he takes everybody from royalty to the homeless down with him, and Jasmine knows she wouldn’t be much of a princess if she let that happen.

The 2019 remake of Aladdin develops Jasmine as a leader of her people somewhat. Actress Naomi Scott’s new solo “Speechless” gives the princess some character depth, underlining that she doesn’t want to be “locked in a cage” of any kind or by anyone because she doesn’t feel seen or heard that way. Additionally, the remake lets Jasmine interact more with common people other than Aladdin, and removes the problematic scene of her “seducing” Jafar. That said, it is actually the original animated Jasmine who stands up for her people the most and shows potential as a leader. The live action Jasmine gets the title “Sultan” (not “Sultana”), but she never directly stands up to Jafar or for the people she holds dear. Thus, the original Jasmine does a great job of keeping true to the spirit of her character, the historical hardships of women of color (WOCs), and the modern potential of fictional and real-life women.

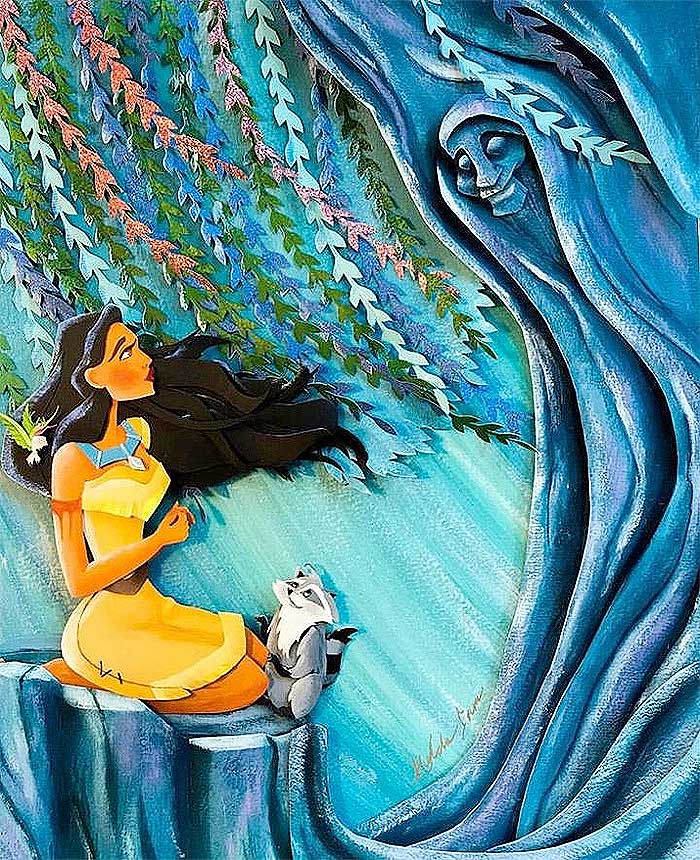

Pocahontas, Pocahontas: Prejudice-Shattering Princess

In June 1994, Disney gave us our second prominent POC with Pocahontas. Pocahontas is the first “American princess,” daughter of a First Nations chief. Unfortunately, a lot of viewers and critics found and continue to find Pocahontas’ title and story problematic. Pocahontas as a movie has a terrible reputation for being historically inaccurate, and said reputation isn’t unearned. Disney executives and animators have admitted they glossed over or outright ignored the true tragedy of Pocahontas. Namely, the real Pocahontas was only about twelve when she met John Smith and John Rolfe. She was forcibly rechristened “Rebecca,” quite possibly forced to embrace Christianity, and was taken to London as what amounts to a curiosity, where she eventually died of disease in her early twenties. Those who justify the film’s historical inaccuracies point out the truth would never fly in a Disney film because of the target audience. But all debate about historical accuracy vs. Disney whimsy aside, Pocahontas still has much to teach her fictional cast-mates and real-life viewers.

Pocahontas, aged up to late teens in her story’s Disney version, is as spirited and strong as Jasmine, if more understated. Like Jasmine, she’s poised to marry a man she doesn’t like (she objects to warrior Kocoum because “he’s so serious.”) Unlike Jasmine, her concern does not rest simply on non-princess identity formation. From her conversation with spirit guide Grandmother Willow, we learn Pocahontas seeks the right path for herself. In other words, she’s not opposed to marriage if it’s her choice and what is best for both herself and her tribe (though we gather Kocoum wouldn’t be her first pick for a husband anyway). Pocahontas analyzes and speaks to Grandmother Willow about dreams and images that point her down her path, such as the dream of a “spinning arrow.” When Grandmother Willow teaches her how to use her inner voice, Pocahontas discovers “strange clouds” are coming, possibly delivering another clue to her destiny. She’s eager to meet them, but again, only after wise counsel and reassurance.

The “strange clouds” turn out to be massive sails on ships bringing the first white men Pocahontas or her people have encountered (we see no female or child passengers). A naturally curious princess, Pocahontas wonders about the white people and finds her mind full of questions when her father, Chief Powathan, expresses caution. Indeed, she might feel more than a bit cagey herself; when she first encounters John Smith, she runs from him and tries to get away in her canoe. But Smith offers a peaceful greeting, and through her inner voice (“listen with your heart”), Pocahontas communicates with him across a language barrier. This touches off a friendship unheard of if not outright forbidden in both cultures. Pocahontas and Smith bond over such things as exchanging greetings, talking about objects from compasses to corn, and as per Disney, uniting in a joyous song.

Yet this writer would be remiss if she said Smith and Pocahontas experienced the typical idyllic Disney romance. They are well aware of their racial, cultural, and other differences, which almost break them apart more than once. In a crucial scene, John Smith rhapsodizes about what he and his fellow colonists will do in the New World. “We’ll build roads and decent houses…we’ll show your people how to use this land properly. We’ve improved the lives of savages all over the world,” he claims. Pocahontas is not impressed. “Savages!” she challenges. “Not that you’re a savage,” Smith backpedals, but Pocahontas doesn’t buy it. “Just my people!” she exclaims. She goes on to explain the fatal flaw in Smith’s thinking–people who are “savages” equate to anyone who is “not like [him].” The song “Colors of the Wind” ensues. Refreshingly though, a quick song does not resolve all the tension in the film, nor should it. The continued tension gives Pocahontas a stronger motivation and a deeper arc.

As Pocahontas’ story progresses, the people who are white and Native Americans quickly conclude the other group is “dangerous.” At first, danger isn’t obvious, but then a tribal man is wounded in a skirmish wherein both parties claim they were attacked first. Powathan decrees no one in his tribe is to go near the white people, although Pocahontas and Smith keep meeting in secret. Eventually, this leads to Pocahontas’ friend Nakoma lying for her, Smith coming under suspicion for being too friendly with the local “Indians,” and Kocoum getting fatally shot. The shooting occurred because Kocoum caught Pocahontas embracing and passionately kissing John Smith. Thomas, a young friend of Smith’s, shot the warrior to defend him. This inspires Powathan to tell his daughter Kocoum is dead “because of [her] foolishness.” We don’t know how the chief discovered what happened or how much he knows, but he is intimately familiar with his daughter’s impulsive nature, so we can presume he knows everything. Failing that, Pocahontas’ tendency toward naive innocence means her body language or other behavior could have given the truth away earlier.

Up to now, Pocahontas’ actions do not mark her as a princess who is concerned for her people or the greater good. She looks more like a selfish princess who is willing to throw her life away–perhaps literally–for a man she has barely met and may well not be a good match for. Yet Pocahontas, and Disney, have a few surprises for viewers. When Kocoum’s shooting touches off a war, Pocahontas is naturally concerned because John Smith has been sentenced to death as its first casualty. Yet again, she seeks wise counsel from Grandmother Willow. Yes, viewers see, she wants to be with Smith and celebrate their love, but she is more concerned about how a war will affect both people who are white and Native Americans. She rushes back to her village with a double-pronged intention–save her new love yes, and more importantly, stop violence born of groundless prejudice.

When Pocahontas returns and throws herself across John Smith’s body, she confesses she loves him and warns her father that killing him means killing her. In the next breath though, she speaks to the immediate situation in light of the bigger picture. “This is where the path of hatred has brought us,” she says, issuing a collective challenge. She goes on to ask her father what his path will be now that he knows what she chooses. Thus, she places the decision to go to war back in his hands, implying the choice between peace and hatred is an individual decision no matter how it affects others. The choice must be made wisely, and Powathan chooses peace for himself and the tribe, but not without giving his daughter due credit. “She comes with courage and understanding,” he says, and in that moment, courage and understanding do define our heroine. They continue doing so when, in a move no princess before has made, Pocahontas says a presumed permanent goodbye to Smith so he can recuperate safely in his homeland.

Pocahontas is not the first Disney film whose main characters overcome prejudicial barriers. What makes Pocahontas stand out among other characters is that she is in a position to speak for an entire nation. Unlike other characters who fall into the offensive “Magical Native American” trope, she’s not endlessly patient or sympathetic either with people who are white or Native Americans. She’s aware that she doesn’t exist to be a “teachable moment,” and will not put up with that attitude. Instead, Pocahontas focuses on overcoming cultural barriers rather than building tension or suggesting one side or the other must completely abandon their culture or values. She keeps the greater good of both nations in mind, impulsiveness notwithstanding. In fact, juxtaposing Pocahontas’ fictional story with the darkness of her true one has inspired both white women and WOC to speak truth to atrocities committed on both sides, trying to heal the old ones and prevent new ones.

Esmeralda, The Hunchback of Notre Dame: Honorary Princess Fighting for Equality

Summer 1996 saw Disney trying to rebound from the critical and box office disappointment that was Pocahontas. Their next feature film choice, a heavily softened version of Victor Hugo’s novel, seemed strange to many people. Hunchback lives far off Disney’s beaten path. It’s not a fairy tale and doesn’t star a princess, chief’s daughter, or any other iteration of the character type. However, Esmeralda is considered an honorary princess in most Disney circles (along with Megara, Vanellope, and a few others). Close analysis proves its female lead Esmeralda could more than qualify as an honorary POC with much deeper troubles than our white princesses, or even our first two POCs, have ever encountered.

More than Jasmine or Pocahontas, Esmeralda begins her story already up to her eyebrows in conflict. She wasn’t born into royalty and doesn’t have a tribe, so to speak. She lives in circa fourteenth century Paris where her people the Romani are a definite minority. Esmeralda’s exact heritage is unclear; she is not a white European but could be Spanish, Greek, or perhaps from northern Africa or southeast Asia. What is clear is that her people are discriminated against and grossly misunderstood. “They’re Gypsies; they’ll steal us blind,” a mother warns her small child in passing when said child stops in the street, entranced by Esmeralda’s dancing. Hunchback’s villain, Judge Claude Frollo, loves singling out the Romani as particularly demonic and dangerous, although he considers everyone but himself to be the lowest of sinners. Unlike nobler characters such as Quasimodo and Phoebus, Frollo uses the term “Gypsy” as the slur which we regard it as today, and means it as such. Partially, perhaps wholly, because of this constant discrimination, Esmeralda is assumed to be impoverished, as are other Romani. In one scene, a Parisian family is caught harboring some Romani citizens, implying their group is used to living on the run.

More than the other two POCs we’ve covered, Esmeralda could be completely selfish and no one would blame her, princess or not. Nor would anyone blame her for seeking marriage and/or a more comfortable lifestyle. Instead, Esmeralda’s travails have shaped her personality, passions, and perhaps mission in life. She stands up for justice without a thought for her safety when she sees Quasimodo stripped, and humiliated at the Feast of Fools. Later, after finding sanctuary at Notre Dame, she grouses to an archdeacon, “What do they have against people who are different, anyway?” Here, she willingly lumps herself in the same group with a handicapped and facially deformed man, the one person who might be worse off than she is. Esmeralda goes on to muse that if just one person could stand up to those like Frollo, maybe her life and others’ lives would improve. This culminates in a sung prayer on behalf of the world’s outcasts, which Esmeralda sings directly to a representation of the Virgin Mary holding a baby Jesus, as well as some saints depicted in stained glass. In other words, Esmeralda is willing to put herself at further risk by approaching the ultimate Authority of a church where she is not in good standing, on behalf of anyone who is experiencing what she does.

Esmeralda’s ahead-of-her-time mission for equality continues when she meets Captain Phoebus. The military man is a new transfer to Paris and under orders from Frollo to eradicate the Romani people. He immediately discounts the assignment–“I was summoned from the wars to capture fortune-tellers and palm-readers?” Thus, when he meets Esmeralda, he doesn’t arrest her. Since they are within Notre Dame’s walls at the time, he urges her to claim sanctuary. When Esmeralda remains silent, Phoebus lies to Frollo, saving her for the moment. Still, Esmeralda doesn’t trust Phoebus any further than she can throw him. Their first one-on-one interaction consists of Esmeralda making snarky comments, including a curse cut short, and improvised sword-fighting with a candle stand. By the end of the scene however, Phoebus finds Esmeralda intriguing for her intelligence, wit, and fire as well as her beauty. For her part, Esmeralda has taken the first step in facing her own prejudices against soldiers and associated authority figures. She’s not ready to claim Phoebus as an ally yet, but she’s starting to recognize acceptance must extend to people of all backgrounds, even and perhaps especially those who mean no harm but were placed in terrible positions. Viewers might infer this gives her more common ground with Phoebus, as Hunchback’s version of the Roma shows that some steal or engage in trickery to survive, just as Phoebus must “play along” with the majority to avoid severe physical, mental, and career repercussions.

Once Esmeralda confronts others’ prejudices and her own, she’s in a better position to make a final stand in the climax, and cement herself as an honorary POC who successfully defends herself and others. Most viewers remember the climactic scene of Hunchback when Esmeralda is nearly burned at the stake and spits in Frollo’s face to show a final act of defiance. But from a closely analyzed and adult perspective, this scene is about a lot more than the defiance of villainy, corruption, and objectification of women. Those elements exist and are important, but we can’t forget how Esmeralda got to that point. Frollo caught and arrested her because she nursed and abetted a wounded Phoebus first, and because she was willing to trust Quasimodo–an ally, but also a non-Roma who had been raised to think her people were evil–with the location of the Court of Miracles. More than Pocahontas, Esmeralda puts aside her prejudices, past trauma, and mistrust to make a point–namely, it is wrong for Frollo to abuse, objectify, and try to physically or emotionally kill anybody, not just her. More than Jasmine, she puts herself directly in the villain’s hands for the greater good, and also for the good of herself as an individual. That is, Esmeralda is willing to die if it means Frollo, on the smallest scale, won’t get what he wants. She finds a striking, interesting balance between fulfilling what is good for her, plus what is good for others, in a way our other two POCs arguably didn’t.

Esmeralda lives, and she and Phoebus become instrumental in helping Quasimodo find acceptance in Paris. Here then, we see the first time a POC–or perhaps any person of color in Disney–finds and facilitates acceptance across race, cultural, ability levels, etc. It’s also hinted Esmeralda and Phoebus may marry or at least pursue a serious romance, Disney’s second but arguably more successful example of a mixed relationship. Esmeralda becomes the first heroine of color to fully and successfully complete a goal arc that is not entirely about her selfhood, romantic goals, or lifestyle. She might not be a princess in the classic sense, but she opens the door for following princesses and honorary princesses of color to continue her legacy in different ways.

Mulan, Mulan: Honorary Princess, Honorable Daughter

It would be two years before Disney gave us another female heroine, much less a female lead. In summer 1998 though, Mulan and her movie burst onto the big screen to great fanfare. Fa Mulan of early China was quickly hailed as a feminist icon. Like Esmeralda, she has no connection to royalty whatsoever, but unlike Esmeralda, Mulan was almost instantly accepted into the formal Disney Princess lineup. Mulan has been hailed as a role model on the grounds of color, gender, and breaking the norms of both. Then again, the other POCs we’ve discussed arguably did those things first, so what makes Mulan stand out as much as she did in 1998 and still does 20 years later?

Much of the praise Mulan receives comes from her decision to take her aging, ill father’s place in war, thus risking her life and shattering gendered expectations. It’s praise she deserves, especially as a POC and especially in her culture. Up to now, no white or non-white Disney princess or honorary one has ever consciously gone against gendered expectations, though they might say they’d prefer to (see Jasmine). The “wow” factor goes up though, when you remember the kind of culture Mulan lives in. Her culture leans heavily on the concept of honor vs. shame. That is, positive attention or deeds honor not only the person, but her family and society, while negative deeds shame the person and the greater group. Mulan’s society prizes family honor, which for a girl meant submissiveness and ladylike, demure behavior. Mulan is an only child who tries to embody the gold standard for a Chinese girl, but finds she can’t. Therefore, she feels the pressure of bringing shame to her family. Mulan’s father is in fact scolded in the movie because he didn’t “teach [his] daughter to hold her tongue in a man’s presence.” From Fa Zhou’s actions, we infer he loves Mulan as is, and might have purposely treated her leniently. However, he does acknowledge, “Mulan, you dishonor me” when she can’t make a match and speaks out in front of men, if only to try to save her father’s life.

None of this makes Mulan’s culture bad. Mulan can no more help or change her roots any more than our other three POCs could change theirs. However, Mulan’s experiences do make it harder for her to fit in, although she doesn’t experience color-based oppression. They also force her motivation to be two- or even three-pronged. On the surface, she goes to war to save her father’s life, and as her song “Reflection” shows, another layer exists in her quest to find out who she is. Additionally, a third layer can be found in the desire she expresses to sidekicks Mushu and Cri-Kee–“[I wanted] to prove I could do things right.” For the first time, we hear a Disney heroine expressing external and internal motivations, uniting them, and struggling to keep them balanced. In this three-pronged quest, we also see a Disney POC embarking on a journey that, for the first time, does not directly involve oppression, because while gender norms exist, it is implied Mulan wanted to bring honor to her family and culture through marriage and feminine pursuits. This takes the role model potential of POCs to a new level, as Mulan shows that a female of color’s trajectory need not revolve around subjugation for her to do great things or help others.

In addition, Mulan is a “first timer” of sorts among POCs because her quest, as she planned it, ultimately fails. She engineers an unexpected plan to save her platoon from enemy soldiers, but is critically wounded and unmasked as a woman when a doctor examines her. Had General Li Shang not owed Mulan his life, she would’ve been killed on the spot. As it is, she’s left wrapped in a blanket, half-naked with her hair down, in the snow, after being told she committed “ultimate dishonor.” She has failed to help her nation against enemies and perhaps more importantly, failed her family and herself. When Mushu tries to comfort Mulan, she explains how unworthy she feels. “I wanted…to see someone worthwhile,” she says, using a discarded helmet like a mirror. “But I was wrong. I see nothing!” With that line, Mulan shows how she doesn’t see herself as important to the big picture of her family, China, or existence. It’s the first time we’ve seen any princess question her motives, admit perhaps they were selfish ones, or doubt whether she belongs anywhere at all.

Fortunately, Mulan’s story doesn’t end in despair. When the enemy soldiers she thought were vanquished turn out to be alive, she saddles up and heads back to civilization, determined to share the truth no matter what anyone thinks. This goes about as well as one might expect, but Mulan’s tenacity sees her in good stead. Again, she’s the mastermind behind a somewhat unorthodox plan to rout the enemy. Better, she’s able to combine her feminine and masculine interests and skills within it. That is, she uses her defense training, and “outs” herself as an illegally disguised soldier for shock value, to give her platoon-mates time to act. But she also uses her shoe and a fan as weapons, not a sword, completes the final fight in a dress, and approaches the emperor as a woman, not a man. Her persistence and ingenuity are rewarded when the emperor credits her with saving China, gives her his crest and the sword of Shan-Yu, and offers her a place on his council. But Mulan is not content to let her victory rest with assurance of worthiness and selfhood. She respectfully declines and heads home to face her father, not knowing what his reaction will be but hoping for his approval and honor more than anyone else’s.

Rather like the Biblical prodigal son–or daughter, as it were–Mulan returns home subdued and repentant. The first thing she does is kneel in front of her father and offer gifts, perhaps in a placating gesture. She doesn’t mention that she’s safe or well, or approach Fa Zhou with any confidence, showing her growth is incomplete. Fa Zhou helps Mulan end her journey when he cups her face in his hands, perhaps giving her permission to look him in the eye in a culture where this wouldn’t be allowed. Ignoring the material possessions, he says, “The greatest gift and honor is having you for a daughter.” He adds that he missed her terribly, and draws her into an embrace. Fa Zhou’s actions effectively cancel out the dishonor and shame heaped on Mulan when her ruse was discovered, both on a cultural and familial level. Mulan, too, succeeds in adding another new dimension to the plot arcs of princesses of color. Her final scenes not only unite personal and large-scale motivations, but also show how big arcs can be encompassed in smaller ones. To wit, the saving of the Chinese nation means the end of Mulan being underestimated for her gender, meaning girls in her nation can expect more opportunities and better standing in family and society in the future.

Tiana, The Princess and the Frog: Princess of Tradition and Innovation

After Mulan, Disney turned most of its attention to non-fairy-tale, non-legend, and non-traditional narratives. Some features, such as Tarzan, were still done in 2-D animation, and there were still plenty of non-white characters, such as Lilo and Nani from Lilo and Stitch. But the story of the princess, or the epic heroine of any stripe, seemed gone for good as Disney sought to focus on innovation, technology, and “regular” girls pursuing “regular” lives and hobbies. It would be 2009 before Disney gave us another princess, and as with Mulan, this princess would make a splash.

Tiana is the first heroine since Jasmine who is actually called a princess. She’s drawn in 2-D, giving Disney traditionalists a breath of fresh air, and giving more innovative fans a reason to enjoy “the old ways” of doing things. The big reason Tiana caused a stir in 2009 though, was that she was Disney’s first African-American princess. Yes, there had been a true princess of color before in Jasmine, and yes, Pocahontas, who was considered a princess, was from 1600s Virginia, not a far-off kingdom. However, no princess until Tiana had the trifecta. She had the title (she marries into royalty, but The Princess and the Frog makes her crowning a foregone conclusion). She was American, and she was a princess of color with ties to African nations, where people of color are usually the majority.

Tiana was set up to become the most progressive princess in Disney history, but she sparked some controversy. In the earliest drafts of The Princess and the Frog, Tiana was called Mamie or Mammy, and served as a chambermaid, which many African-Americans justifiably found anachronistic and offensive. After Tiana was given a makeover with a new name and a new role as a waitress and aspiring New Orleans restaurant owner, audiences remained suspicious. How would Disney portray a 1920s black female protagonist? Would she be overly submissive or cater to the stereotype of black women as sassy, brassy, and off-putting? Worst, would her story revolve only around gaining a prince, and thus having an “easy out” when it came to discrimination and subjugation? In regards to the final movie, the answers depend on who you ask. No character can please everyone, and Disney females in particular have a rough go of it. With that said, Tiana acquits herself well, carrying on Mulan’s tradition of uniting the microcosm with the macrocosm–and uniting much more in the process.

Tiana sets herself apart from other princesses, white or non-white, pretty quickly, while maintaining some commonality with her forerunners. Like Jasmine, she doesn’t like the idea of being a princess, but for Tiana, the dislike comes from a practical standpoint. Princesses don’t have the same dreams and goals she has, nor do they live in the “real world.” In the princess world for instance, you have to kiss slimy frogs to find your true love, and Tiana is not a frog fan. Like Mulan, Tiana is also close to her family, especially her father, but unlike Mulan, she shares her father’s dreams and hopes. She wants to honor him with the opening of a restaurant while still making the dream hers, like with signature recipes for beignets (Daddy was more a gumbo man). Like Esmeralda and Pocahontas, Tiana is also aware oppression and obstacles to her goals exist, as her song “Almost There” elucidates. Interestingly though, the strength of family love and a rather unusual friendship with rich white peer Charlotte have insulated her from much of the pre- Civil Rights fallout of 1920s New Orleans. She’ll let on to overwork or discouragement with a crestfallen expression or heavy steps now and then, but she doesn’t take kindly to naysayers. “Getting close” and “almost there” have kept her going for years and she’s not about to give up now. “Don’t you worry, Daddy. We’ll be there soon,” she promises once, placing a fingertip kiss on her deceased father’s photo. She’s right, but it’s going to take a unique journey, tailored to Tiana and her era, to get her all the way “there.” As she finds out, the ultimate goal includes much more than a restaurant.

Tiana’s story takes a turn toward the old Disney classics, with a modern twist, when she goes to buy the local sugar mill for refurbishing. At first, the two white male real estate agents are eager for her to close the deal and pay them her hard-earned cash, but at the Mardi Gras ball later that night, it all falls apart. Tiana learns she was outbid, and one agent comes out and says, “A woman of your…background? You’re better off where you at.” It’s a slam to Tiana’s spirit, a modern equivalent of Cinderella’s stepmother telling her she will always be a ragged servant girl. Tiana is so crushed, she puts aside her “up by the bootstraps” work ethic and takes a page out of fanciful Charlotte’s book. “I cannot believe I’m doing this,” she whispers while looking out at the first evening star, adding a fervent, “Please, please, please!” The only response she gets is from a croaking frog on the windowsill. “I reckon you want a kiss,” she says–then screams in terror when the frog, also known as Prince Naveen, replies in the affirmative. Once again, the mixture of modern goals and traditional means push Tiana to the next phase of growth.

Tiana kisses Naveen in hopes he will turn into the prince he says he is and help her resurrect her dream. She ends up as a frog instead because as she tried to tell Naveen earlier, she’s not a princess, just a waitress. Naveen is highly perturbed, and his attempt to explain the situation sets Tiana off, too. “You mean to tell me this all happened because you were messing with the Shadow Man?” she demands, adding on that he’s a “spoiled little rich boy” and she doesn’t have time for his nonsense. As fate would have it though, the two unwilling amphibians are thrown together over and over, as they must escape the Mardi Gras ball, a thunderstorm, and a treacherous bayou stretch to stay alive. They eventually learn a priestess and practitioner of “white voodoo,” Mama Odie, can help them become human again, and Tiana is ready to throw Naveen under the proverbial bus for her chance because she feels he doesn’t deserve his. But in the course of their journey, Tiana learns Naveen has some strong good qualities. He’s intelligent, funny, and doesn’t sweat the small stuff. He’s able to find the bright side in most situations, such as when he and Tiana are captured and nearly eaten thanks to a couple of stereotypical bayou rednecks. Like Esmeralda, Tiana must confront her misconceptions in order to deal with the underestimation she has faced.

Despite this lesson, Tiana remains wholly focused on becoming human again as the way to get her restaurant, fulfill her dream, honor her father, and yes, rise above the “place” she’s been pigeonholed into. For example, one of her attempts to bond with Naveen involves teaching him to mince mushrooms. It’s a sweet moment, and one Naveen needed because as he explains, he’s never had to work at anything. Like Tiana, he’s a person of color, but his royal heritage has kept him sheltered from a lot of what being a POC means in this era, such as hard work and the expectation that you “prove yourself” to “earn” what others get because they’re alive. However, the mushroom scene also emphasizes Tiana has not yet faced her greatest flaw. She’s all work and no play, to the point that she has trouble relating to people and activities outside of work. Additionally, her all-consuming work ethic has caused her to look down on people who do less, or don’t have as much experience as she does. She doesn’t do it intentionally–she’s usually kindhearted–but Tiana can and does come off as a “work snob” with a sort of reverse classist attitude. When Naveen tries to romance her, this attitude and the ensuing fears, such as the fear of never being good enough, cause Tiana to rebuff Naveen and run away.

It takes Mama Odie, a wise grandmotherly type a bit like Grandmother Willow, to mentor Tiana into a much-needed realization about her priorities. Tiana comes to her full of hope, speaking so fast she trips over her words and expecting an easy “fix” to hers and Naveen’s little green problem. Mama Odie has other plans, though. Through a rollicking Gospel-inspired number, she explains Tiana must “dig a little deeper” to find out what she needs, vs. getting what she wants. Mama Odie tells Tiana she has her daddy’s same spirit, but that his love, not his work, is what she should focus on. By the time Tiana and Naveen leave Mama Odie’s, still frogs, but with a counter-spell in hand–er, flipper–Tiana hasn’t absorbed this lesson just yet. However, she’s well on her way.

Tiana makes a final unique stand for girls and women of color when she confronts Dr. Facilier, AKA the Shadow Man. In the climactic scene, he offers her a deal with the devil, as it were. If she turns over the talisman Facilier uses to control voodoo spirits, he will give her all her dreams, including the restaurant. Facilier pushes this temptation as hard as he can, reminding Tiana of how she’s been subjugated and underestimated, and how her “poor daddy” never got his dreams ostensibly because he was black. This line of thinking speaks directly to anyone who’s been oppressed and might consider underhanded means to escape said oppression. It may speak especially to women of color, who have been oppressed for centuries on at least two counts, almost from the moment their ancestors set foot on European or North American soil. Tiana’s adamant refusal of Facilier’s deal, and the way she uses her frog tongue to destroy his talisman, is therefore all the more cheer-worthy. The moment the talisman breaks, so does Tiana’s inner oppression, as well. She finally realizes being good enough, proving herself, or improving her life are not tied to the physical or external. They are tied to the things she loves to do, such as cooking. More importantly, they are tied to the people she loves and how well she loves them back. The final scene showing Tiana’s restaurant in all its glory gives us a final union of microcosm and macrocosm. The new Tiana’s Palace feeds the stomach with wonderful food and feeds the heart and soul with deep familial and romantic love.

Moana, Moana: A Princess for All Realms

Moana is our final POC, who debuted in 2016. She is of traditional Polynesian heritage and, like Pocahontas, is a chief’s daughter. Like Tiana before her, Moana unites some of the traditional motivations of princesses with modern and unique twists. For example, she longs for the ocean although she’s been warned to stay on land, in a sort of reversal of Ariel and a callback to Jasmine, who longs for life outside the palace. Moana is also impulsive and athletic, defying “proper lady” stereotypes like Mulan and Pocahontas. Her story arc, though, may be the biggest and most daring Disney has attempted for a POC to date. Her journey encompasses safety and honor for her family and the prosperity of her island nation, giving it ties to Mulan and Tiana’s arcs. Moana, though, is the only princess so far whose journey also involves direct spirituality and an inner struggle that connects her to the universe as a whole.

The film doesn’t waste any time connecting Moana to a realm larger than herself or the spiritual forces within it. Moana’s people are dependent on island crops like coconuts and fish, but at her story’s outset, an encroaching “darkness” is destroying these crops. The people are left vulnerable to famine and other disasters, and it is up to Moana, the chief-to-be, to help them cope. However, Moana and her father disagree on how to eradicate the darkness. Moana’s father and the other adults in her village would prefer she stay on the island, using crop reserves and de facto tools until further notice. Moana, however, gets right to the root of the darkness. A demigod named Maui has stolen the heart of Te Fiti, the life force that keeps the island prosperous. Moana knows the only way to prevent famine and destruction for good is to go into the ocean, find Maui, and get him to restore the heart of Te Fiti, which appears as a small green token Moana carries with her after the ocean entrusts it to her. In fact, the ocean’s choosing gives Moana the confidence she needs to step out of her imposed comfort zone. She isn’t simply being defiant; she’s being called upon for an overarching mission and answering to a much higher authority than a parent or a cultural hierarchy.

That said, Moana’s journey is much harder than she anticipates. Simply making it over the reef in a homemade boat nearly drowns her, hearkening back to her father’s worry of losing her the way he lost his best friend. Once Moana finally makes contact with Maui, getting him to heed her is all but futile. Maui is sanguine and lovable, but also full of himself. Of course, he is a demigod, but his self-absorption gets in the way of doing a demigod’s duties, namely restoring the heart of Te Fiti. Moana must take on a task of persuasion, which none of our other POCs have undertaken for a significant time in their films. Restoring the heart and saving her island also requires Moana to form an amicable relationship with Maui, a task made harder because Maui can legitimately claim he’s always right while Moana is always wrong, misguided, or foolish. In fact, Maui enjoys pointing this out, mostly by calling Moana a princess repeatedly, much to her annoyance.

In a new move for a Disney heroine of any color, Moana combines diplomacy and direct persistence to make Maui see her point of view. “I am Moana…you will board my boat…and restore the heart,” is her impassioned refrain. She also matches Maui comment for comment when he tries to get under her skin. At the same time, she opens herself up to listen to his story–namely, a story of being rejected by earthly parents and taken in by demigods when he was too young to understand their power. At this juncture, rather than a climactic moment, Moana realizes she could’ve handled Maui differently, and begins counting him as a true friend. Viewers of a spiritual bent might see this as her making a stronger, more mature connection with the universe or her spirituality.

These overarching connections continue the closer Moana and Maui get to Te Fiti. One of three antagonistic forces they face is Tamatoa, a huge crab with an affinity for shiny objects and a vendetta against Maui, who once injured him with his fishhook. In some ways, Tamatoa is a version of Maui with his self-absorption and carelessness overblown. Moreover, Tamatoa could be seen as a Jungian “shadow twin” for Moana. Specifically, like Moana, Tamatoa sees what he wants and goes after it, obeying the “inner voice” or “inner urging” to get his desires whether or not that voice is correct, mature, or what is best for him. He’s prideful and stubborn in the worst ways, losing his temper if he is ever questioned or corrected. The major difference is, Moana set out her journey to help and honor others; she still acknowledges others as having a place in how her life works out.

Still, Moana can’t complete her arc until she acknowledges her weaknesses, as well as some truths regarding what her journey is really about. When Te Ka nearly kills her and Maui, nearly destroying the fishhook, Maui abandons Moana. “We’re here because the ocean told you you’re special, and you believed it,” he accuses. Moana, like Mulan before her, is left alone and hopeless. “You must choose someone else; I failed,” she tells the ocean in despair. But like Grandmother Willow and Mama Odie, Moana’s Grandma Talla is there to give her granddaughter a reality check. She reminds Moana “the call isn’t out there–it’s inside [you],” and “there’s nowhere you could go where I won’t be with you.” In other words, Moana’s longing for the sea, her destiny as chief, and her mission to restore the heart were never only external. They were about who she is as a person and how she fits into her world. This realization, coupled with Grandma’s wisdom, inspire Moana to retrieve the heart, reunite with Maui, and face Te Ka with an ally by her side. Ultimately, she learns Te Fiti, a goddess, has been deceived about who she is as well, and saving the island entails remembering who the goddess truly is.

Like most of the POCs before her, Moana comes full circle when she returns home. She brings with her changes, such as the freedom for her people to regain their standing as voyagers, as well as an end to the darkness and poverty of the land. Again though, the best thing Moana gains is internal. She embraces her role as chief–yes, princess if you will–and finally feels confident in placing her signifying stone on the island’s mountain. Symbolically, her stone is a pink conch shell whose design calls back to the hair ornament she wore as a toddler. In choosing it, she accepts both roles, a ruler of the ground and a lover of the sea.

Can White Princesses Have Arcs Like These?

A reader or viewer might wonder, why haven’t white princesses had the arcs and journeys we’ve discussed? Several reasons come to mind. For one, many of the white princesses were created in eras where women of all colors were still finding their footing in the wider world. They were not considered major players in the workforce, leadership, the pursuit of human rights, or much of anything outside the home. But even “modern” white princesses like Ariel, Belle, and even Rapunzel and Merida, tend to stick to the “escaping marriage/escaping expectations of self” arcs largely because their narratives, not just their skin colors, are white.

When we say certain princess narratives are “white,” we mean they don’t center on themes like cultural oppression, denial of human rights, and the direct, immediate breaking down of barriers. The white princesses do engage in some of this. Belle faces opposition because she’s considered snobby or “as crazy as [her father].” Rapunzel has to break through the physical and emotional barriers an abusive guardian places around her, and Merida has to prove herself as a competent female ruler, with or without marriage. Yet their oppositions remain small in scale, and less direct when it comes to cross-cultural relations and the formation of identity outside negative self-concepts. People of color, people of non-majority religions, and people with disabilities, to name a few, have faced these obstacles where white people might not have faced them at all, or at least in different ways. Thus, the princesses of color distinguish themselves as women who can speak uniquely to centuries of oppression and overcoming. The Disney narrative needs more female leads like this in the new decade–as many African-American, Latinx, or other minority voices as possible.

Can or will white princesses ever have overarching journeys that speak to these themes? Recent Disney developments say yes. With the advent of Frozen II, we have two white, Nordic sisters–one a princess, one a queen–facing what it means to be true to themselves, their kingdom, and the spirituality that influences their universe. Elsa in particular deals with oppression themes, as she struggles with her sometimes debilitating introversion and associated ice powers. There are in fact some writers and critics, such as Helen Tagler-Flusberg, who speculate Elsa is on the autism spectrum. Tangled, while dealing with smaller-scale goals, does see Rapunzel finding and reclaiming her place as ruler of Corona, something she was never supposed to claim. The Wreck-It Ralph duology gives us Vanellope, an honorary princess dealing with both a “glitch” and its place in her selfhood, plus finding the true world she can call her home. Still, Disney movies featuring white heroines haven’t been quite as brave as ones featuring POCs yet. The movement toward diversity and inclusion, regarding characters, motivations, and arcs, continues as we enter a new decade. While it does, let us look forward to seeing big motivations and fully realized journeys from princesses of all colors and backgrounds.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Moana and Mulan are definitely my favourite Disney princesses. So independent. And the music in their films is amazing!

Also, Moana actually looks and sounds like she’s 16. A first for Disney.

I grew up Asian American, partially in Hawaii so when Moana came out I was ridiculously excited to finally have a princess from a culture that resembled one I saw somewhat growing up. I cried watching the trailer. I cried off and on throughout the whole film during my first viewing and to this day I get goosebumps when I hear the soundtrack.

Funny thing is, I’ve talked to a lot of people who still haven’t seen the film because they didn’t have any interest in it. It’s a harsh reminder to me that diversity in Disney is still a serious issue.

It’s all about historical accuracy. I’m definitely here for more diversity in Disney princesses 100% but like do your damn research and quit fixating solely on skin color (because that’s really just trying to put a bandaid on the issue) and instead help showcase different cultures. Heroes and villains come in all shapes, colors, and sizes. They come from ALL walks of life and from EVERY corner of the world and I am so ready to see that shit.

I literally was just having this historical accuracy conversation with a friend the other day. You won’t see black characters in the regency in shows like Reign or the Tudors because that just didn’t happen back in the day. Those shows are supposed to be relatively historically accurate. It’s sad and disappointing that such a time existed (and in many cases still exists) in society, but I don’t think it’s correct to change a show for representation. That would also be a case of skin color diversity instead of cultural diversity since I highly doubt any black character in the regency would have had any cultural differences were they actually written into the show.

You should submit this article to Disney!

I would personally love to. Do you happen to know where or how to do that?

There was an article in the now-defunct Premiere magazine many years ago about how the colour film used by Hollywood was basically developed to show ‘white’ skin to its best advantage and how it had difficulty registering detail on black skin. I think that is a very interesting things to discuss.

I never looked to fairy-tales and cartoons based on them for anything approaching social realism.

I appreciate your article so much Stephanie! I would like to note that Princess Jasmine was played by a white woman — something that saddened me to learn. Disney continues to perpetuate so many ideas of “whitewashing” and has refused, until very recently, to have princesses represent women of other races and cultures. We have come so far but have so far to go!!!

I remember I dyed a Barbie´s hair as a child because I wanted her to be a brunette like me. Have you watched Pocahontas 2? Its not even close in quality to the first one, but I got really surprised about HER choice of prince

I have, and yes, that was definitely a surprise. I’m not sure what Disney’s motives were in creating Pocahontas II–if they wanted to recover from the inaccuracy backlash, they certainly did not do that. But, bless their hearts, they tried, I guess?

I am saddened by how Esmeralda has been more sidelined – sadly I’d not even heard of her…

She’s a really interesting character and very unlike other Disney women.

And God Help the Outcasts is one of the best songs in a Disney movie. It’s so powerful.

She should be of North Indian decent hence her skin tone and Romani gypsy background. I don’t know how the article got that wrong!

Jasmine has always been a favorite for me and I really like Tiana – my daughter actually just watched The Princess and the Frog. My daughter also doesn’t only watch Disney (at least I try my best so that that is not the case) and I think enjoys the music more than anything.

I loved Jasmine as a child! She was the first real kick ass Disney princess that I remember.

Fantastic post. The princesses of color are outcasts, but they are also shown as “less feminine”. Mulan posed as a boy, Pocahontas ran unescorted in the woods, Jasmine stood her ground even in the face of all-powerful Jafar, and Tiana focused on her business. Even Merida, for being a white princess, is a little bit of an outcast because she does things better than a man that isn’t singing, dancing, cooking, or cleaning. Elsa, Bell, Ariel, Snow White, and Cinderella all needed a man to get them out of their situations. Disney banks off of white, feminine women who know their place. Should we ask Disney to make colored, feminine, 1950’s-era princesses?

Good point, and no, we shouldn’t. Here’s the thing. I think if we *did* ask Disney to make 1950s-era POCs, they would instantly say, “But that’s anti-feminist and anachronistic.” Which is odd, because it’s like, why can’t they see their earlier white princesses the same way? It goes back to the question of why white princesses have never had these arcs, and if they ever can. Personally, I’d like to see it, but as you point out, Disney is not, nor has it ever been, a bastion of equality.

Best article on this topic I have ever read.

Thanks!

An enjoyable essay. Watching the evolution in Disney princesses since the 1950s, this essay provides a way to develop a perspective on changes for the better.

As a writer of Caribbean heritage, I also agree that the Disney Princess brand must expand its horizons. Since the brand has a massive global influence, it only makes sense that the princesses should represent all girls of every ethnicity, and disability.

Right there with you. I’m obviously white, and I’m a Protestant, but I also have a disability. It continues to discourage me that more than other minority groups, mine is largely and summarily ignored, except when people want to make us “inspirations” for breathing or say we are burdens on society.

I don’t think necessarily that being a woman of color has given these princesses more opportunity to chase bigger dreams. I do however agree that because of the era some of the princesses were born into, and the cultural and systematic structures society had on these women, they had less to “deal with” basically saying like you, that their expectations for what they wanted for their lives were smaller. Really up until a few decades ago, it wasn’t “their place” to dream bigger or do more. So I do love the acknowledgment here and of course, the idea that these women of color hold themselves a little higher in regards to their own dreams and ambitions because they’ve had to speak up for themselves at a young age because no one else would. Great article here! Opened my eyes a little more into the lives and dreams of women, their color, and the society they were born into all to portray an image to an audience.

Absolutely. I think what we have is a case of women of all colors and backgrounds being subjugated in one way or another, which I hope will eventually not be the case. Then again, we live in a broken world, soooo…

Something sad I witnessed with my little nieces- Jasmine is always shunned because she’s not “pretty”. To my eye the princesses are the same element line drawings but for coloration and clothing styles. So what is the level of prettiness based on? Race, right?

Right, and it’s discouraging that yet another generation of little girls is absorbing that sort of thing.

Wow at Jasmine not being seen as pretty by some girls. It’s so sad and scary when thoughts like that start so young. And marketing doesn’t help when those princesses are left out more often than the white princesses.

Wow, great observations!

Jasmine was always my favorite as a little girl, she has a pet tiger!!! It doesn’t get any better than that. I always look for her when I see Disney Princess stuff and quite often she is not included. It’s a real shame because she is a great character and very pretty as well.

We watch all the Disney films and my daughter loves all the princesses – Mulan was her favourite until Frozen came along – I don’t think anyone will ever replace Elsa now. I asked her why and she said ‘because she has magic and is powerful’ – fair enough!

That’s a good enough reason – I think Elsa’s pretty great too.

I think it’s great that Disney is having black heroines – a bit more diversity would be welcome for lots of reasons. Having said that, I don’t think Disney heroines are something to identify with. I am white and grew up in a white town and Disney stories were never more than exotic fairy tales to me too.

I feel the same way about the sexism and racism in school books debate. I think it’s great that school books have moved on, there is ethnic diversity, girls can be heroes etc, but growing up with the likes of Peter and Jane, I never took the mother in a frilly apron to be a vision of reality. Frilly aprons just didn’t exist in our house and to me the books were obviously fiction.

Yes, there is a distinct line between fiction and nonfiction, and there is no such thing as politically correct history. The goal of this article and others like it is, I think, not to identify directly with characters so much as analyze what they *can* contribute and teach.

Why a princess?

Why is it that all she has to do in life is get married to some prince?

If you had kids you might know of Dora the Explorer o Dora la Exploradora she’s a bi lingual Mexican/American girrrl who goes out and using a map finds lost things whilst having to overcome various obstacles on the way.

My boys watch her all the time … they have NO interest in princethings.

You have Jasmin, Mulan, Pocahontas, Tiana, Moana…. do I need to go on? So I don’t think Disney is white washing (anymore).

Yes, there have been many strides over the past two decades to add more princesses from different cultural backgrounds. However, the problem with half the princesses you just mentioned, though, sabrina, was that each of them were highly altered from their original story (except for maybe Moana and Mulan).

Jasmin was dressed inaccurately for her culture and time period. Pocahontas was completely inaccurate from the historical version. Tiana (according to a good source as I have never seen the movie) spent most of her screen-time as a frog, instead of as a black woman.

As such, while disney has made attempts to add more representation, their attempts to do so have often been for naught as they still managed to screw up by not paying attention to the cultural aspects of the princesses they are including.

I want to make a note that they could have done WAY better with The Princess and the Frog. Disney’s first Black Princess movie not only supports harmful tropes and stereotypes about Southern Louisiana/Creole culture but she’s a damn frog for the majority of the movie. She has hardly any facetime as a princess so we as black women didn’t really get representation as a Disney princess….we got a frog.

Good point there. I’d certainly be upset if they finally gave us a princess with a disability, only to turn her into a bird or cat or something. Or worse, cure her in the third act.

Wow, I had no idea she spent most of the movie as a frog. While an adorable story it may make, it definitely does not offer representation for young black girls. That is such a shame. I can’t believe they botched that up too. (I mean, i kind of can and that’s just sad.)

Esmeralda is my favourite. Thanks for including her. Funny how we can get such strong emotion for characters that are not real. Personally I hope Disney makes a live action movie with Meghan Markle starring in Hunchback.

Esmeralda is a favorite of mine, too. She’s in my top five Disney princesses or honoraries. I’d love to see a live-action actress tackle the Disney iteration of the role, although I question whether it would be done justice. My concern would be that, as with Jasmine, she’d be played by a mixed-race actress who looks white, thus appeasing the majority. My other, somewhat more pressing concern is that she’d be played flat and like a distressed damsel in the name of toning her down.

Hopefully a live action will be done soon. Aladdin was so good.

I dunno–I feel like this article sets up a dichotomy of passive white woman/active woman of color, which I don’t think is really fair. It’s important to note as well that, although all the characters you mention would be POC to us, they wouldn’t necessarily all be POC in their own societies–Mulan, for instance, is the same race as all the other characters in her movie, and almost certainly, so is Jasmine. Another way to look at it is, do you think that Disney intentionally makes its non-white princesses more active because it feels like it can’t “get away with” a passive non-white character who just wants to get married (for example), in the same way it could with a white character?

Good question Debs. I think Stephanie has noted an important trend. Hopefully by pointing out this discrepancy there will be change.

In interesting discussion. I’m a little unsold though as I think it is great to praise these changes I am still not sold on Disney’s genuine desire to demonstrate change – I think they have had better success in their portrayal of topics and issues then they have had in their gender development. But thanks for continuing the discussion.

On the one hand, if it ain’t broke don’t fix it right? With the recent DC Wonder Woman and the new Marvel Natasha Romanov character driven flicks I think as appetites change for stronger female characters, eventually film studios will follow suit.

Look at the backlash from Ghost in Shell.

My sister so wanted a black ‘barbie’ doll when she was little – I think she saw the doll on holiday somewhere and asked for it for her birthday back at home. My parents had to really search to find this doll – it was the late eighties; the days before the internet and so meant going round the toy-shops and asking for catalogues etc but after months of searching they did find her. I have to admit, I would have thought things were better nowadays but apparently not.

I had an Aladdin doll – I thought he was by far the most goodlooking of all the Princes and actually still do!

The only black doll I ever had was American Girl’s Addy (in the mid ’90s). My parents never said I couldn’t have them, but I guess it just never occurred to me that white girls could play with dolls of color. Looking back now, I wish I had. I actually find dolls of color more attractive than white ones now.

Wow, this is a wonderfully written post and definitely relevant! I definitely see how in a lot of YA books authors are taking into account various types of diversity whether it be culture, gender, etc. However, if authors choose to do this they also need to look at life through the eyes of people of other cultures instead of automatically imposing Caucasian views on everything.

I agree, and it’s a bit of an “ouch” in a good way. I’m working on a dystopian novel where the protagonist is legally blind. She’s also Caucasian (because I want to focus on disability as a minority and her journey to live in the world with one). But one of her mentor figures, so to speak, is a WOC, and a very dark young woman at that (late teens). I’m trying not to focus on it since (A) My MC wouldn’t see it or really care and (B) I’m not a POC and don’t want to get anything “wrong.” But do you think I should say some more about that? What would be your thoughts on showing this person as an authentic WOC?

Hi Stephanie,

I have an article you may find useful about this topic.

Lorber, J. (1993). Believing is seeing: Biology as ideology. Gender & Society. 7(4), 568-581.

Looking forward to reading your novel.

Munjeera

That is part of being realistic and being a good author. Anything else is simply lazy.

Amazing post! I like how Disney’s stepping out and giving representation to other cultures, even though I don’t know how accurate the representations are. Then it’s more important for Disney to portray it correctly!

It is very good to see Disney making some serious changes to be more inclusive of people from around the world. However, at least half of those princesses have had serious inaccuracies or problems and Disney’s latest attention (the live action Mulan movie) just goes to show that Disney hasn’t figured anything out. They are still making the same stupid choices they did in the past. If Disney wants to continue making progress, they need to stop making stupid, white-biased choices, but I am unaware of who is in charge of writing the stories and doing the casting at Disney so perhaps that is half the problem.

True, and since Disney is such a big name and not everyone (esp kids) has had previous knowledge of other culture, the responsibility they have is a lot bigger. Hope they fix that for upcoming movies :/

While Disney has made attempts to be more inclusive, they are still falling quite short by ignoring the cultural aspects of the princesses they are creating.

You have a good point there. They totally made up Pocahontas’ entire story, which, I kind of understand that, but I think it’s way too romanticized. As for Jasmine, Moana, etc., I see now that they took the easy way out. I think Disney is afraid of exploring non-Caucasian cultures for any number of reasons, and that fear is translating into a new generation of xenophobia.

Why couldn’t Disney have done a story about a real African princess? They would have had a beautiful chance to educate the world on some African history that didn’t involve colonialism and slavery and tell a nice story at the same time. And why is the love interest not black, as well? Surely, if there’s a paucity of positive pop cultural icons for black girls, there is just as just as acute a lack of positive images for black boys?

I would love an authentic African princess. Again, can’t speak to it personally, but I’m absolutely sure people of African descent in any country get sick of being associated primarily with slavery and colonialism. I’d also like to see such a princess with deep, dark skin tones and her hair down, drawn in an authentic, textured fashion. (For example, the only place I’ve ever seen Tiana with her hair down is in fan art. She looks AMAZING with her hair completely down, and I wish Disney had taken advantage of that).

Great read! These princess mustn’t be forgotten. I remember getting some Disney barbie dolls when a child. My favorite was Jasmine. My parents made efforts to get me barbie dolls of color so I had a wider range of representation in my toys. Jasmine was always a favorite of mine, especially since I discovered Mulan and Pocahontas much later for example.

Jasime sticks out because she’s the only one who’s not the lead in her film. Other male lead Disney animated films never become part of the Princess line, even if they had Princesses (Black Cauldron and The Lion King). I know BC is ignored because it mostly flopped (I think it’s an unaccredited influence on Zelda).

In Beauty and the Beast both are technically equally the title characters. But it is still Belle who is the active Protagonist. If you reversed the genders of the characters the Beast wold be labeled a damsel in distress.

Thank you for your passion on this topic and for your detailed article.

While reading this, it occured to me that interestingly enough the first three princess movies do at least pass the Bechdel test. Which I know is not the be all, end all of whether or not a movie is feminist, but it’s always nice to have. In fact, all of the Disney princess movies except for Aladdin pass. And I think if one had to not pass, it should be the one named for the male protagonist, and the only one that’s really more his story than the princess’ anyway. Kind of a nice overall trend, that they can at least manage that bare minimum qualification throughout all the movies, when there are so many movies that don’t meet it.

This is such an interesting and thought-provoking piece. You’ve done a fantastic job of analyzing these films, and I’ve especially enjoyed your thoughts on the character arcs of the princesses of color and their dynamic in the Disney Princess universe. Thank you so much for sharing this with us!

I understand how people are looking for stories that includes their own culture and characters they can identify with. But they do exist. I think Disney is catching up on them as well, slowly but surely. Not that i watch many disney stuff, but i’m aware of the most popular princesses.

With Disney, it’s all about 1 colour; GREEN! They know the black princesses will never sell in the same numbers as the white, because black people don’t spend a lot o money on Disney products, vacations, ect. Same with “Barbie” – how many leftover black Holiday Barbies are left unsold while the identical white versions sell out? PLENTY!

My little cousin likes Tiana but she doesn’t show as much love for jasmine/mulan/Pocahontas because their outfits aren’t traditional princess dresses. That small thing means so much when it comes to admiring one culture over another.

The concept of childhood and the circumstances as well as the environment in which children are raised has changed over the years and I’m happy to see that Disney is in for the big road.

My sister who is african-american loves princess and the frog because its a princess who looks like her. We need more POC princesses.

It is a really exciting time for Disney, they are finally reaching out and representing a range of cultures. It would be nice to see a Latina princess next, or an African princess not based in America and by which their cultures and traditions are represented

I really liked the points this article brought up about POC in Disney film culture. It only shows that we need more POC in Disney films due to their historical and social contexts in the modern world.

Very interesting post! I’m a blogger who runs a Disney blog from my own perspective as a woman of color, and these are issues that I think about often when considering the Disney canon. You did a great job of breaking things down.

Change needs to begin at the grassroots level if we hope to ensure that there are no more repeats of the George Floyd incident. A welcome move by Disney that needs to be replicated by all studios to ensure that nobody is discriminated against merely because of the amount of melanin in their skin.

A good article all around. I think there is no doubt that white princesses will have overarching journeys that speak to the themes you highlighted. I was going to point out Tangled as well, as she first tries to figure out her place in the world and new responsibilities (in Season 1), discover more about her past (in Season 2), and returning to Corona (Season 3) to fulfill her “total birthright.” Although you say that “Disney movies featuring white heroines haven’t been quite as brave as ones featuring POCs yet,” that’s not completely true, as Rapunzel was brave in the animated Tangled movie, and White princesses have showed bravery in their respective movies. Besides, if there are more POC princesses, all the better! Sure, there can be White princesses now and then, but they should not be the majority of those in such stories. There need to be more POC princesses (or princess-like) characters, such as Luz Noceda in The Owl House, or Cleopatra “Cleo” in Cleopatra in Space. In any case, the princesses you mention have improved the Disney princess narrative, without a doubt.

Hey! Amazing article! It was very inspiring and I used it as a source for an essay I needed to write. I would really like to give you credits, but that means I need your full name. So my question is: what is your last name? Thank you in advance!

@Irene: My last name is McCall. I’m so glad you liked it, and that you want to use me as a reference!

I completely understand the points, and I always love watching Esmarelda and Mulan. The emperor’s new groove was perhaps Disney’s biggest flop when portraying non-white cultures. The white-washed cast and not exactly Latinex names goes too show Disney isn’t always successful in its exploration of other cultures. This article points out what I’m always thinking while showing me new ideas. Absolutely amazing.