Disney and the Perils of Adaptation

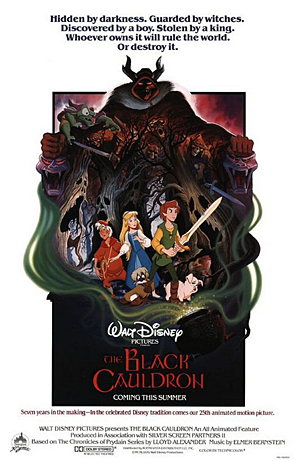

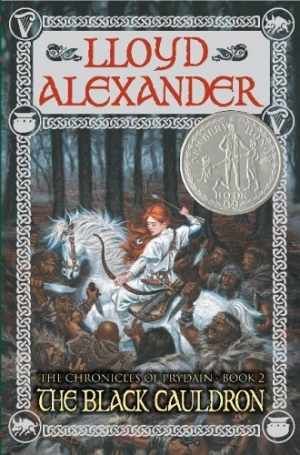

Disney, unlike, say, the BBC, has never been known for a high level of fidelity to the stories and novels it chooses to adapt. While not a bad thing for fairytales and folktales which originate with no particular author and have historically wide variation, Disney runs into problems when it tackles the works of a single, recognizable author. Not only do such films risk critical derision, but they often suffer from basic story issues. However, despite dancing with death a number of times, it was not until the release of The Black Cauldron, based on Lloyd Alexander’s successful fantasy series, where this free and easy approach to adaptation translated into both a critical and commercial failure, perhaps the worst failure in the studio’s entire history. Though this instance was one of the first and few times Disney’s typical looseness with source material translated to an abject flop, The Black Cauldron is nevertheless indicative of a trend in Disney storytelling that only became more pronounced as time wore on. While many of their films could serve as indicative cases of this trend, we here shall pick out The Black Cauldron, The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Frozen as the exemplars. These films give us by far the most prominent examples of where this less than strict approach to the works of others leads them headfirst into trouble on the level of the story.

The Black Cauldron: Disney’s Darkest Hour

As said before, The Black Cauldron suffered the most disastrous release of any Disney film, savaged upon its initial release by critics and audiences alike, the most virulent criticism coming from fans of this five-part fantasy book series. To this day it remains the black sheep of the Disney canon, not even receiving a VHS release until 1998, thirteen years after its theatrical run. Besides the uneven plot and darker elements, most of the ire stemmed from something Disney never before bothered itself too much about: namely, lack of fidelity to the source material. Granted, it had caused some problems before–Mary Poppins’ author, Pamela Travers, left the premiere of the Disney film in tears and Rudyard Kipling’s widow never forgave Disney for mispronouncing Mowgli’s name–it never faced such universal derision and indifference before from its audience. The question is, why?

While much of The Black Cauldron’s problems stem from its tumultuous, thirteen year long production, just as much stem from the bizarre story choices made in adaptation, and the source material necessitating a darker tone out of step with most Disney releases. How dark, you ask? The film underwent extensive re-editing prior to release, primarily for the scenes involving the Horned King and undead Cauldron Born, avoiding a PG-13 or R rating, being the first Disney film to receive a PG rating. Now remember, these were the days when the PG rating was handed out much more sparingly, and thus had far more weight behind it. Also remember that, after the death of Walt Disney, the studio floundered badly, remaining moderately successful, but nothing like the powerhouse it had been for the preceding decades. Compare a seventies Disney release, such as Robin Hood, to the last film made under Disney’s watch, The Jungle Book, and you can see well what sort of creative and financial difficulties the studio suffered under in the seventies and eighties.

Disney underwent a major power shift during the production of this film, transitioning from the old guard of the “Nine Old Men” who worked some of the most significant films under Walt’s leadership, to Jeffrey Katzenberg and the animators who would lead Disney into the “Disney Renaissance.” Having been in production for thirteen years and coming just as this transition shook things up, it has the misfortune of capturing both the weaknesses of the old style of Disney, and the uncertainty of the new. Beginning, arguably, with The Jungle Book, stories in Disney films tended toward the more episodic, with a general goal or theme uniting the different episodes, but, with few exceptions, most of the scenes present little vignettes of their own, fun but not exactly essential. Though the limited scope of the seventies films reflect the restrained budgets they suffered under, it also reflects the creative uncertainty plaguing Disney animators and directors without the clear guidance of a genius like Walt Disney. Disney bought the rights for The Chronicles of Prydain in the hopes of returning the grand, ambitious projects like Fantasia and Sleeping Beauty, but the creative and financial restraints not only drew this process out to absurd lengths, but imbued the film with a damning uncertainty of how far to go in either direction–is this a more comedic lark, like most Disney releases, or would they more faithfully capture the darker tone of the novel? The one would keep their traditional audience of families and children, but the other would compete with the darker tone of eighties’ family films.

By 1985, when The Black Cauldron hit theaters, the trend in family-oriented cinema had left the more typical Disney style of film-making for something darker and edgier, with unsettling imagery, increased violence, and language, as exemplified in films such as E.T., Labyrinth, and The Secret of NIMH. Disney, undoubtedly, felt in order to compete in this new market, it needed to release something along these lines, to fit in with this unsettling and darker tone in family film-making. The emphasis on which probably prompted many parents to stay away, thereby depriving the film of a substantial portion of its audience. The problem, which is evident simply by watching the film, is, with a few exceptions, Disney just doesn’t “do” dark all that well, at least not like this. Disney does light-hearted, crowd-pleasing, artistically brilliant productions, sometimes light on story, but brimming over with charm and great characters. The sort of moodiness exhibited by eighties children’s films clashed badly with Disney’s traditional aesthetic, resulting in the “tone problem” Lindsay Ellis identifies as plaguing many later Disney releases, and succeeded in alienating its core audience more than anything else.

This “tone problem,” however, stems from a much deeper problems with the story. The film is split between two different stories, and thus tells neither of them well. Lloyd Alexander’s fantasy novels were undoubtedly inspired by Tolkien’s high fantasy, but his reliance on Welsh mythology gave a different sort of cohesion and interest to the material, and his focus on the teenage characters of Taran and Eilonwy thus made it more accessible for the emerging young adult market. The first novel has a familiar pattern of an adventure lark, with Taran, the “Assistant Pig Keeper” for Hen Wen the oracular pig wanting to prove himself with noble and daring feats of heroism, as Arawn the Death Lord and his lackey the Horned King beginning to tighten their grip on the land of Prydain. His endeavor to find Hen Wen after he lets her escape leads him introduces him to a cast of characters accompanying him throughout the rest of the story, scatterbrained and opinionated Princess Eilonwy, wannabe bard Fflewdur Fflam, and the repulsive looking, but harmless, Gurgi. Learning heroism involves much more than sword slinging and glory, he emerges from the adventure successful, but wiser, reckless enthusiasm tempered.

The second, like any good sequel, builds on the characters and world of the first to tell a more mature and somber tale, where the endeavor to destroy the Black Cauldron, a magical piece of crockery creating legions of undead Cauldron Born, forces Taran to give up not only wonderful, unasked-for gifts (the brooch that gives him prophetic dreams), but even the justly earned credit of finding the thing for the sake of fulfillment of his quest. Though they utlimately succeed, it comes with enormous sacrifice, specifically in the person of the vain and friendless Prince Ellidyr, who, before mocking Taran and demanding the credit in exchange for his assistance in delivering the cauldron, with his final act throws himself in the Cauldron so it might be destroyed.

The film, having the unenviable task of combining these two stories, preserves the basic storyline of the first book, while grafting on the climax of the second. The combination of two disparate stories into a ninety minute film involves some necessary compression: done well, this can be to the story’s benefit, removing dead air and filler for the sake of a more streamlined story. Done poorly, it can obliterate the narrative structure and logic, and leave characters without any reason for acting as they do, or even existing in the story at all. The film mostly follows the plot of the first book, though it conflates Arawn the Death Lord and the Horned King (not, in itself, a bad idea), excises Gwydion, and in addition the the quest for Hen Wen, grafts on the the quest to destroy the black cauldron, shoehorning in the scenes with the witches, making the climax a modification of the second book’s, with Gurgi throwing himself in rather than Ellidyr–only, whereas Ellidyr never returned after giving himself up, Gurgi is restored to life by an appearance of the three witches, and the friends saunter off together into the sunset.

Though conceptually it doesn’t seem like a disaster, the problems in execution become immediately evident. Even under passing scrutiny, the story collapses in on itself. By seeing so much of the Horned King, we lose so much of the mystique Arawn the Death Lord exercised over the story with his unseen, seeming all-powerful menace. By removing the stopovers among minor villains (like Achren, Eilonwy’s sorceress aunt), we blunt the edge of the Horned King’s menace and make him seem more incompetent than was surely intended (never mind losing the necessary narrative logic and backstory of characters like Fflam and Eilonwy). Why does he leave so many in his dungeons, rather than taking the more logically ruthless step of killing them? If he is cunning and powerful, how is it three people escaped unscathed and untracked and the bipedal puppy could free his friends undetected?

Pulling back from character work and looking at structure, it is clear that combining the disparate stories of the first two books gives us two unrelated conflicts, two competing tones, and two different MacGuffins, Hen Wen and the Cauldron. Knowing The Black Cauldron was the most popular of the five, though the plot of the first was more accessible, they tried bringing the two together without accounting for these differences of maturity and tone. The struggle to give weight to the two competing conflicts of these books divides the focus and diminishes the stakes. Is Hen Wen more important, or the Cauldron? Is Taran learning what true heroism consists of, or that true heroism involves irrevocable sacrifice? What does the Horned King even want? All these underused side characters–do they actually serve a purpose or are they just around to provide a little color to the unfocused proceedings?

The film can’t decide which it wants to be more, The Book of Three or The Black Cauldron. It wants the clear adventure story plot of the first book, and yet the darkness and maturity of the second. Again, these are two completely different stories. You can’t tell two stories at the same time and still expect an audience unfamiliar with these books to care. The film shifts from grotesque and violent at one moment, to cutesy and colorful the next, the traditional Disney aesthetic clashing violently with the high adventure of the first novel and the somber maturity of the second. You can’t be everything at once to everyone–in trying to combine all the “best” elements into one film, they reveal a total lack of understanding of basic story logic, shoehorning two conflicts and plots together that have very little to do with each other, giving the film it’s only conflict, a conflict of interest.

The overarching character arc of these five novels is Taran maturing from a petulant boy who dreams of glory for its own sake to a man humble enough to know where real glory lies. Taran might not be the most interesting among the novel’s extensive cast, but he, as a sheltered teenager with little experience of the strangeness and beauty of Prydain, provides a vantage point for readers coming to this mythology for the first time. The reader experiences the magic and danger of Prydain as Taran does: thus, Taran’s character arc is the thread tying these retold myths into a cohesive whole. While The Book of Three illustrates this with a more typical “hero’s journey” a la Joseph Campell, The Black Cauldron makes Taran and his counterpart, Prince Ellidyr, face stark, harsh choices in order to exercise and grow in maturity. The exchange with the witches of a cool sword for the Cauldron in the film simply does not compare with the bitterness of Taran’s sacrifice in the book, first of the brooch, resigning the credit for finding it to Ellidyr. Nor does Gurgi’s sacrifice in the film have the same weight as Ellidyr’s in the book, since, unlike Gurgi, Ellidyr “stays dead,” knowing that, despite his previous selfishness and bloated sense of his own merit, he had nothing to lose or to gain, finally putting the good of someone else above his own pride and glory. Taran matures tenfold in this story, but that maturity comes from the harsh lessons of an unforgiving world. Despite the magic, battles, and sword fights, this is a far cry from the more accessible lark of the first book, having irrevocable, bittersweet, even cruel consequences and choices more typical of Pixar or Studio Ghibli than Disney in general.

Split between these two stories, the film waters down the harsh maturity second novel watered while draining the fun from the proceedings of he first. It seems Disney saw the visual and cinematic potential of these stories (and the animation, even thirty years later, is still impressive in places), but neglected the character work that makes an epic succeed. People loved Lord of the Rings because the hobbits are both fun to follow and give us a vantage point for entering into Tolkien’s world; The Chronicles of Prydain anchors readers into emotional reality by having the focal point of the fantastic stories be the relatable arc of a boy learning to become a man. Disney saw clearly the externals (a fashionably and innovative dark tone with the possibility of incredible visuals), but seemingly forgot what makes any of these worthwhile. Focusing so much on how it looked and how dark it felt, it failed to understand what gave the novels their appeal in the first place, and thus failed to communicate that to a larger audience, leaving fans outraged and more casual viewers confused and uninterested. The attempt to keep up with the trends in family film-making–in this case, dark and imbued with fantastical elements–resulted in a bland, uneven film that didn’t know what it wanted to be except fashionable. Considering the mega-flop this film was, you’d think Disney learned its lesson and never used a respected literary work for fairly mercenary means again, right? Alas, no–post-Walt, this is exemplary of a cast of mind which would re-emerge periodically during the years of and following the Disney Renaissance.

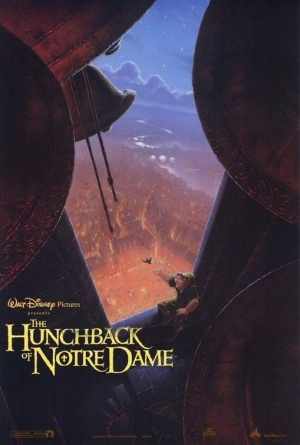

The Hunchback of Notre Dame: or, Victor Hugo Rolls in His Grave

By the time the year 1996 rolled around, the dark days that birthed The Black Cauldron were long forgotten, by Disney and the film-going public. Their public image and financial clout improved significantly with the release of The Great Mouse Detective in 1986, and under the business leadership of Katzenberg and the creative guidance of Ron Clements, John Musker, Glen Keene, Howard Ashmore and Alan Menken, 1989’s The Little Mermaid blew audiences away and once again made the Mouse the undisputed king of family animation. 1991’s Beauty and the Beast surpassed the high expectations created by The Little Mermaid, becoming the first animated film nominated for Best Picture, and 1992’s Aladdin, while not receiving as many glowing reviews, drew enough box office revenue and critical acclaim to cement the era we now call the “Disney Renaissance.” After years of making mediocre, meandering films, sometimes not bad and other times awful, never rising above “okay”, it seemed Disney had at last recovered the financial and creative glory the studio enjoyed under Walt’s leadership. However, as the old saying goes, “pride goeth before a fall”.

Pocahontas in 1995 saw the first real misstep of the era, where using historical events for a fairytale like story plunged the studio headfirst in controversy, both for its disregard of historical accuracy and a questionable portrayal of Native Americans. For the first time, Disney’s slightly irreverent attitude toward its source material was no longer excusable–since the film dealt with real people and events, people were far less willing to overlook a “Disneyfied” take on the story. Reality, ironically, caught up to them. Though they didn’t learn their lesson right away–it took Victor Hugo to do that.*

Disney’s version of Victor Hugo’s Hunchback of Notre Dame, while nothing like the catastrophe of The Black Cauldron, yet received a more mixed response than most other Disney films released since the beginning of the “Disney Renaissance,” courting a significant amount of controversy for the more mature content, on the one hand, and the “Disneyfication” of its source material, on the other. Since it was well into production during the disappointing release of Pocahontas, they had no time to backpedal on the mature themes, which the film-makers had amplified for the forthcoming film. Victor Hugo’s novels will never be accused of lightness or fluffiness, which from the beginning worked against Disney. Since the story upon which they drew has an almost oppressive tone of fate and inevitable tragedy, revolving around several men lusting after a sixteen year old girl, the most prominent being a priest, it was obvious this film would handle some themes and subject matter atypical of Disney’s family oriented films. In fact, it’s probably the darkest Disney picture since The Black Cauldron.

A major plot point, indeed the driving force of the novel’s plot, is the character of Frollo, a judge (priest in the novel), whose lust for a much younger woman, the gypsy Esmeralda, drives him to desperate, cruel, and unthinkable actions, first to posses her, then to destroy her. The song “Hellfire,” one of the best and well-remembered songs from the film, encapsulates this struggle in three breathtaking minutes, while illustrating all the major problems in this most unusual and uneven Disney flick. Though written in such a way as to escape most children’s notice, it’s still unavoidably the soliloquy of a man tormented by and then succumbing to his lust for a much younger woman. Disney’s dealt with the macabre and violent, but never with the sexual so frankly. While less prominent, there are other examples: passing use of words like “strumpet” and “licentious,” “damnation” and “hell”, as well as tackling weighty themes of bigotry coupled with a questionable examination of Medieval religion and hypocrisy. Not even Pocahontas, one of the more mature (and bland) of the late 90’s Disney offerings managed to tread so far into dangerous waters–most Disney characters, then and now, can’t even utter the name of God. The character of Esmeralda herself raised some concern–or at least, Disney’s interpretation of her, which involved casting actress, Demi Moore, who at that point was something of an “erotic provocateur” (her film Striptease having been released mere weeks after Hunchback). Such connections, coupled with the mature content inherent to the novel’s story, certainly gave many, not just parents, pause. Disney’s decision to even think of picking up the Hugo novel raised some eyebrows from the start, and the finished product did little to lower most of them.

Not the least due to the inconsistent amount of “Disneyfication” littering this film. Now, before we move on, a working definition for this sometimes nebulous term should first be provided. Merriam-Webster defines it as “the transformation (as of something real or unsettling) into carefully controlled and safe entertainment or an environment with similar qualities,” and, according to TV Tropes, it involves “[rendering] a story “safe” for juvenile audiences (or the parents thereof) by removing undesirable plot elements or unpleasant historical facts, adding Broadway-style production numbers, and reworking whatever else is necessary for a Lighter and Softer Happily Ever After Ending.” Despite the presence of so many child-unfriendly themes, there still exists many Disney tropes considered essential for a successful Disney film in the 90’s–to wit, we have incongruous comic relief sidekicks in the much derided singing gargoyles, slapstick humor scattered at seemingly random intervals (including, but not limited to, the intense climax atop the cathedral), a protagonist who just wants “something more” out of life (Quasimodo joining the illustrious ranks of Ariel, Belle, and Jasmine in that regard), and, most notoriously, a happy ending, the mishmash of such themes leading to Disney’s severe late 90’s “tone problem.”

As with The Black Cauldron, however, understanding where the film went wrong hinges on understanding where Disney’s grasp of the story falters. Since summarizing Hugo’s novel is almost as complicated as actually reading it, and compiling a list of differences between the novel and the film would take another piece of its own, we shall instead examine one standout example of the great successes and curious failure of Disney’s take on this material. A successful adaptation of the story lives and dies on the treatment of the tragic figure, Frollo. If you don’t get him right, one might argue, you don’t get the story right. Having already looked at “Hellfire,” let’s examine the other standout musical piece from the film, the number that introduces it all and puts Disney’s story in motion, “The Bells of Notre Dame.”

Hunchback features some of the greatest music of any Disney film (namely “Hellfire” and “The Bells of Notre Dame”), but even those are fraught with problems. “The Bells of Notre Dame” is perhaps the grandest opening conceived for a Disney film, introducing the story, the characters, the tone and major themes, coupled with the solemn, swelling majesty of Catholic liturgical chant. Despite these strengths, the questions and plot holes crop up almost immediately: who are these gypsies? Why do they want to go to Paris? Why does Quasimodo look nothing like his mother? Most damaging for the story, is the introduction–or lack thereof–of Frollo, who seems to have been spat out of the mouth of hell 60 years old and thoroughly wicked. Who is he? Why does he hate the gypsies? How did he become a genocidal hypocrite? Why does he wield so much influence; surely the King would have something to say about this? Is he really so evil he can’t see the difference between a woman protecting her baby and one smuggling valuables? While Frollo’s transformation makes the most sense, considering their audience, it does the most damage to the story. We no longer have a devout man, dedicated to his vocation (though having questionable hobbies), adopting a deformed infant out of pity, whose struggles with lust transform him into a monster, but an irredeemable villain from the outset.

The novel is so compelling because the characters, especially Frollo, are so well drawn: without knowing he was the one orchestrating the attempts against Esmeralda, one might even admire Frollo’s charity in taking in a deformed infant no one wanted, instead of, in the film, questioning how such an inflexible bigot could be frightened into adopting a child he tried to drown in a well. His surrender to his lusts drive the major events of the novel: his attempt to kidnap Esmeralda in the beginning introduces both Phoebus and Quasimodo to her, leading to Esmeralda’s fatal crush on the cad and the blossoming of Quasimodo’s affection for her, one can argue the tragic events would never have come to fruition if Frollo had not attempted to obtain Esmeralda. While Esmeralda is the focus of the plot, who everyone seeks to possess or protect, who provides the motivation for our major characters, Frollo has the most agency–his actions set the plot in motion, and, to an extent, determine how it unfolds. Desire for Esmeralda spurs his actions, but while she does little but find herself manipulated by cruel and uninterested authority figures, he schemes about, broods over and engineers her fate, first desperate to consummate his lust, and, when refused, unbending in his quest to see her dead (believing her death will finally quell his lust). The same cannot be said for Frollo in the film, whose uninteresting and vague motivation only provides the obstacle for Quasimodo’s typical Disney protagonist search of self-discovery. By relegating Frollo to the status of supporting character, he loses the complexity and agency that drew so many readers to the novel in the first place. None of these problems exist in the source material, not only because Hugo reveals everything you ever needed to know (and more than you wanted) about his major characters, but, subsequently, the characters are both consistent and sympathetic, or at least understandable (if not condonable).

Hatred and evil are not spun out of nothing, but are drawn from some flaw or tendency of character. Thus, Frollo’s fall arouses both our pity and our horror (essential elements of tragedy, according to Aristotle), because we see how it happens and understand from whence these failings came. In Disney, we are given neither (of the latter), so we get neither (of the former). If this were a typical Disney film with a typical Disney villain, these issues of backstory and motivation would be simpler and less important. But it isn’t: this is Victor Hugo, and his characters make little sense without the comprehensive background and character analysis he provides. Because Frollo is so well-defined in the novel, his lack of definition in the film is a much more glaring weakness, tearing plot holes in the fabric of the story when a better understanding of Hugo’s intentions regarding the character would have prevented this, considering the centrality of his character arc to the story. What is expected in a typical Disney film (“he’s just evil”) becomes inexcusable in a Victor Hugo adaptation. Since Disney can’t commit to Hugo’s controversial antagonist, given their reputation and unwillingness to lose the younger audience entirely, their attempt at darkness and maturity thus falls flat.

Though it may not seem so at the surface, these two aspects, the excessive “adult” themes and “Disneyfication,” are inexorably related as regards this film. It begins and ends with the same problem that plagued The Black Cauldron: namely, lack of fidelity to the source material leading to an uneven and uncertain result. They wanted to bring Hugo’s novel to animated life, and yet be as lucratively crowd-pleasing as their previous releases. Which, as anyone who has read this novel knows, is simply not possible. As Janet Maslin wrote, “the film makers’ Herculean work is overshadowed by a Sisyphean problem. There’s just no way to delight children with a feel-good version of this story.” The two sparring elements of this film are born from this inability to decide how far to go in either direction, which itself is born from the decision to tackle Hugo in the first place. You just can’t make Victor Hugo into a Disney film, and still please everyone.

There is a lesson in this, which can equally be applied to this film, and the previous one discussed: “dark” does not equal “good” (or better). In order to justify an unusual level of violence and somber, more adult themes, there must be some emotional payoff, that wouldn’t work unless those ‘dark’ things are present. You can’t give your movie a dramatic tonal shift compared with your previous releases for no reason–again, darkness in this sense is neither good or bad, but depends on what sort of story you’re telling and what you wish to communicate to an audience. You get darker if that’s what it takes to deliver it. The problem with these films, Hunchback and The Black Cauldron, is, it seems, they wanted something “darker,” not because of the story they wanted to tell, but because either it would fit in with the more popular movies of the time, or it would somehow increase the prestige of the studio. Such considerations, divorced from the quality or requirements of any story, account in part for the tonal inconsistencies of both films.

In truth, the Hugo source material only gives a daring veneer to the project, an illusion they’ve done something revolutionary–though it throws in some dark words and grotesque set-dressing, it rarely breaks out of the Disney tropes and cliches considered essential in Disney’s 90’s releases. We still have our idealistic hero longing to escape his mundane life, our beautiful female lead, noble swashbuckler, svelte villain and playful sidekicks, all dressed up in Hugo-esque costumes. A real adaptation of this material would require alienating the audience of families and reaching out to a much older audience, a risky venture considering the typical attitude towards animation in this country (known to some as the “Animation Ghetto”). But if it were totally toned down…well then, what would be the point? It seems what Disney really wanted, with this release and Pocahontas, was to achieve some level of “sophistication” (probably hoping for another Oscar nomination), trying to one-up Beauty and the Beast. Hugo would definitely get people talking, and Disney would be more than the “kid’s movie” studio.

But, as with Alexander, adapting Hugo is a far different matter than adapting a fairytale. This a two-hundred year old, complex, well-loved and respected novel, challenging readers and critics alike since its publication. Something of this sort cannot be treated with the flippancy typical of Disney (which, to reiterate, is not always a bad thing). Adapting this kind of work for the screen requires a respect that Disney, with its monetary goals and reputation for family fare, simply could not provide. This lack of respect for the source material, coupled with an uneven attempt to appeal to both audiences, resulted it what must ultimately be considered the failure of the film to both make a concrete goal, and to achieve whatever goal it was they sought to attain. Like The Black Cauldron, Disney seemed neither to know nor care what elements were integral to the novel, and what it was Hugo wanted to get across. Instead, it was a vehicle–though, rather than being “relevant”, the goal was “sophistication.”

Frozen: Why Bother, At This Point?

Hans Christian Andersen is notoriously difficult to adapt: the most well-known of his stories are the least bizarre, presenting the most straightforward path to screen adaptation, though even these are laced with implications and nuances most studios would rather ignore. A Disney version of The Little Mermaid was picked up on and off by the studio since the 1930’s, and their version of The Snow Queen floated around for about as long. Though my thoughts on Disney’s treatment of the former have been made known (albeit in a roundabout way) on this site, here I shall discuss my real thoughts on Disney’s ability to adapt Andersen for the screen: namely, they don’t have it.

Why is that? Remember how the failure of The Black Cauldron and Hunchback as films can be traced back to their lack of respect and understanding of the source material: this judgement applies most abundantly to their treatment of Andersen. With The Little Mermaid, they at least preserve the general story line, though ripping out the heart of the story out by giving it a conventional ending and omitting the Christian themes and elements (without which, as I have argued, it is impossible to understand his work). With Frozen, they don’t even preserve the title. Nothing of the film resembles its source material in the slightest degree, whether we speak of the main characters, the storyline, the setting–nothing.

Now, to be fair, this story, and indeed most of Andersen’s work, translates poorly to film (though to call it “dark” might be a stretch). The story is divided into seven sections. The first begins with a demon who creates a magical mirror, “which had the power of making everything good or beautiful that was reflected in it almost shrink to nothing, while everything that was worthless and bad looked increased in size and worse than ever,” twisting even the thoughts of those who looked into it. In attempting see heaven’s reflection in this wicked glass, it slips and shatters, scattering pieces across the earth. Whoever gets one of these shards caught in his eye will see everything in this distorted fashion, and if it gets in his heart, his heart becomes “a lump of ice.” The story moves then to Kay and Gerda, who spend their day either by their rose trees or at her grandmother’s feet, till a shard lodges in Kay’s eye, and another in his heart. He tears out the “imperfect” roses, mocks her grandmother, and abandons playing with Gerda in favor of filling his head with numbers and showing off in front of the other boys. Soon after, during a sled race with the other boys, Kay is kidnapped by the Snow Queen, and Gerda embarks on a desperate journey to save him.

Gerda’s journey is less direct than is needed for a film, and more circuitous, with detours including a witch, a wise princess, and a run-in with a robber girl, before she and her reindeer finally approach the Snow Queen’s abode. She can’t make it past the Snow Queen’s defense until she prays the Lord’s Prayer (a significant detail, since Kay’s failure to remember it allowed the Snow Queen to kidnap him), and when she finds Kay, he is cold to the touch from the Snow Queen’s kiss, feeling and remembering nothing. He cannot leave till he spells out the word “eternity”, but even that he fails to recall. Only Gerda’s tears, and her singing of the hymn her grandmother taught them, washes the shards of the demonic mirror from his eye and his heart, and he remembers her and becomes the friend that he was, the shards of ice forming “eternity” of their own accord. They return home to her grandmother, now grown, and listen once more to the ancient hymn: “Roses bloom and cease to be,/But we shall the Christ-child see”.

Granted, this is a spoiler-filled, involved summary, but needful for our ensuing discussion and comparison. It’s obviously little like the relatively quick and dirty story we get from Disney. It’s in “distilling” it for a film that the folks at Disney reveal their utter inability to “get”, not only Andersen’s intention and the underlying theme, but the ‘rules’ (for lack of a better term) that govern fairytales. Kay’s “frozen heart” makes him cruel and unfeeling; Anna’s frozen heart makes her…more loving? Warm-hearted? More willing to sacrifice herself for the needs of others? Kay’s character arc is consistent with the symbolism, while it is actively contradicted in Anna’s case, leading to a poorly thought out muddle of a climax. Andersen explains his symbolism clearly and logically (though not explicitly)–thus, within the framework of the story, Gerda’s tears washing out the shards and melting Kay’s frozen heart is consistent and satisfying. Frozen fails to establish the ‘rules’ of the magic governing this story, so it seems as if Anna can save herself by sacrificing herself for her sister (who, it has been established, is more than equal to the paltry threat of Hans’ sword), failing to clarify who had the “frozen heart” in first place and how it was to be understood.

And, if we compare the film with its source material, we see its claims of originality and daring are simply not merited. Has a Disney film ever focused on two sisters rather than a guy and girl? Actually, yes–though a supporting character, Lilo’s sister Nani in Lilo and Stitch played a significant role in the protagonists’ respective character arcs. What about one that showed a woman “doesn’t need a man”–what happens to Anna at the end? Kristoff is certainly more than “just a friend.” What about the “twist” at the end, of Prince Charming being a villainous sociopath? First off, Shrek 2, with its caddish and villainous Prince “Charming”, was almost 10 years old at the release of this film; second, in the words of novelist Regina Doman, “What? A rich heterosexual white male turns out to be the villain of the piece? Now THAT’s a trope we’ve NEVER seen before in a Disney movie!” Hans might be more suave and subtle, but as an antagonist, he’s about as daring and inventive as Gaston.

The real shame here is that the original fairytale is as daring, new, and inventive as people claim the film is. Unlike virtually any other Disney release, not only are the majority of the supporting characters female (the dearth of which in recent films has been noted by many critics), but it’s the girl who undergoes the hard and perilous journey to save the boy. Not just, as Doman points out, a nice and sensitive boy, but a “cold-hearted, exploitative, cruel boy: a story that genuinely would have been revolutionary and welcomed by the shortcomings and sorrows of our culture.” The movie we get pales in comparison to the depth and profundity of Andersen’ original, in plot, story, and character, leading, as with the other examples, to an uncertain and uneven result. The main bone of contention is the centerpiece of the film, the character of Elsa, but the uneven handling of her arc (such as it is), affects the rest of the elements in the film.

The main problem is the film doesn’t know how sympathetic, or not, she should be, problems which can be traced to her blockbuster song, “Let It Go”. The character of the Snow Queen, in Andersen’s story, is an ambiguous figure, acting as the antagonist, though her intentions are never clear. By contrast, most initial drafts of the film presented “Elsa” as a more typical antagonist, with intentions obvious as Cruella de Vil. However, the composition of “Let It Go” during production completely changed the character of Elsa from a more typical villain to the misunderstood girl we see in the final film, the story team believing you couldn’t give a villain such a sympathetic song. Thus, they retooled the story to make Elsa more sympathetic, and gave the role of villain to the previously heroic Hans.

But that gives the film a severe problem of perspective: “Let It Go” is a grand, triumphant number about, well, letting go, but in the context of the story, Elsa “letting it go” imprisons Arendelle in eternal winter and isolates her from her sister. Neither of which is, objectively, a good thing. But the filming and staging of “Let It Go” on its own would lead one to believe this is unequivocally a good thing for Elsa. Hans’ revelation in the third act as villain comes after little set-up or time spent with the the character, seeming more a last-ditch effort to raise the prosaic stakes at the climax. Attempting to make Elsa wholly sympathetic deprives the film both of a clear antagonist and coherent central conflict, forcing the writers to present all Elsa’s actions in a favorable light and preventing her from making more consistent and interesting, but less laudable, choices.

Again, the production difficulties with her character stem from failing to understand her in the first place. The Snow Queen’s ambiguity works, because her motivation has no bearing on the story. We never know why she kidnaps Kay, but her calm aloofness, and absence from most of the story while maintaining an undeniable influence over it, makes her motivation irrelevant to the story’s unfolding and unquestioned by us. By never revealing what she intends or desires, and carefully limiting the time spent with her, Andersen gives her a mystique that piques our interest, wielding a significant influence over the story while remaining untouched as befits an elemental spirit like her. Making her the protagonist’s sister and placing her interior struggles at the centerpiece of the film forces the writers to uncover what Andersen wisely hid, unbalancing the story and leaving our heroes with little to do but wring their hands over Elsa’s problems. If the writers had understood why Andersen did what he did, they would see there’s no need for lavishing such focus on unlocking the heart of the antagonist, but instead may have focused their efforts where it belonged, rather than leaving their protagonist, and their story, quite literally in the cold.

“Unbalanced” indeed is an apt word for this film. When we distill the conflict to its bare essentials, we find, apart from some weak attempts to add suspense (Anna’s frozen heart), this whole film could be the chronicle of a minor inconvenience. Despite hogging the focus of the film, Elsa, aside from freezing over Arendelle, is too confused, weepy and “angsty” to pose a substantial threat, igniting the central conflict via a misunderstanding which is smoothed over in less than a few days. Our ostensible protagonist does nothing but turn to ice (and save herself?), and the thinly written antagonists likewise do little to move the plot along. By spending so much thought and energy on who Elsa is and what she wants, when such questions are irrelevant to the original story, the writers turn the antagonist into a hero and deprive themselves of their story. All is in the service of the “deep” and “complex” Elsa, but nothing justifies such focus, and only serves to distract the focus from where it actually belonged. Over analyzing Elsa as a normal girl strips away the dramatic heft and suspense her role can create. The ethereal woman made entirely of ice who rarely speaks and never reveals herself to anyone has far more nuance and intrigue than the X-Men princess whose innermost struggles are laid bare for us from her childhood. Had the filmmakers understood this, we might have been given a film more challenging and compelling than the one that exists.

Kay and Gerda have so much more to gain and to lose in their story, which had a far more epic, yet dramatically focused, scope than anything in Frozen. But that had explicit Christian themes and elements so woven into the fabric of its story, it would be impossible for Disney to remove any of those elements like it would want and still preserve the narrative logic. Therein lies the major problem: though Andersen’s stories are called “fairytales,” they originate solely with him and exhibit his idiosyncrasies as an author, exhibiting his unique sensibilities and preoccupations, differing widely in plot, story, and character from traditional fairytales. These are not, despite their brevity, simple little stories, but can be as complex, opaque, and challenging as anything written by the great poets and novelists. As such, an Andersen fairytale is something unique, originating from his own mind, with his own intentions, purposes and interests, much like a novel, demanding the same sort of respect needed to successfully bring it to life in another medium.

As evidenced by Disney’s previous ventures, that sort of fidelity is antithetical to their method of adaptation and storytelling. Disney will do its “own thing” with a story, which works with a fairytale, but not with something beloved and respected like The Chronicles of Prydain or Victor Hugo. Again, the appellation “fairytale” when applied to Andersen’s work is a misnomer, considering how different and original they are when compared to, say, the Grimm’s fairytales. But the name prevents outcry for the violence done to his tales, as opposed to Hugo or even Alexander. An Andersen story challenges the reader with poignant and stark insights into the more uncomfortable aspects of human existence, and removing these aspects–which one must in order to expunge the Christian elements–leaves the story a weak and empty shell of what it was, a pithy little thing with nothing to offer and nothing to add. It’s no coincidence that Disney’s adaptations of Andersen tend, storywise, to be among their weaker films, despite their financial success.

With Disney’s questionable track record, it’s clear The Snow Queen would never receive the respect it requires to bring it to life. But perhaps if they weren’t still riding on the success of Tangled, we might have gotten something at least marginally better. It seems the same problem plaguing Disney’s less than stellar adaptations resurfaces here, albeit not as evident. While not beginning as a cash grab, the film ended up more like a marketing ploy than a valid attempt to tell a good story. The material, to all appearances, is a vehicle for some ancillary goal. It’s not about the story, it’s about how many princess dolls they can weasel into the hands of little girls at Christmastime. “It all seems so cynical,” writes film critic Christy Lemire, “this attempt to shake things up without shaking them up too much. “Frozen” just happens to be reaching theaters as Thanksgiving and the holiday shopping season are arriving. The marketing possibilities are mind-boggling.”

To an extent, it worked: though financially a far cry from The Black Cauldron, on a story level the two are shockingly similar. Many factors are at work in the success and failure of the story of a particular film, and analyses such as these will undoubtedly involve gross simplifications. But, in the case of Disney and its adaptations, they seem most often to fail when the source material is all but disregarded, and telling a faithful and compelling story takes a backseat to some ancillary and more mercenary motive. When you’re making a film, telling a good story should be your overriding motivation. While concerns of audience appeal and box-office potential are important (considering how expensive film-making is), nevertheless, letting these concerns drive your film ultimately has a debilitating effect on your finished product, leaving you with something weak, uneven, and most damning of all, uncertain.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Great to hear I’m not the only one who was sorely disappointed in Frozen.

I remember seeing Cauldron in the theater — I thought it was for my 10th birthday, but maybe not since it came out in July and my birthday is in September. I don’t remember much about the movie, but remember liking it a lot, and was inspired to read the books, which became my favorite fantasy series as a kid.

I was bored by Narnia and didn’t read The Hobbit until I was an adult for reasons having to do with childhood trauma, Gollum, and the Rankin/Bass cartoon version from the 70s, so this was “my” series.

I watched Black Cauldron again in recent years, and my reaction was “what was 10 year old me thinking?!”

I was 15 when this came out, and had read the books in 5th grade. They were my introduction to fantasy and I loved them. I took one look at the preview for this and knew they had botched it. The fact that the title is actually the title of the second book and the Horned King is not even in it was the first red flag. The Disneyfying that was obvious in the trailer was the second. My friends and I gave it a pass.

I really love The Hunchback of Notre Dame. First, I think the animation and music are just gorgeous. Second, I was just the right age when it came out to be ready to appreciate some darker themes. I’m happily religious but I can still appreciate a movie that points out the evils of hypocrisy, lust, concern only for self/status, etc. Hellfire is probably one of my favorite Disney sequences ever – it’s ostensibly a prayer to Mary/the saints/God, but quite quickly it’s apparent (if it wasn’t already) that Frollo is basically the Pharisee who prays ‘thank God that I’m not like this other guy over here’…and then spirals into something darker entirely.

I swear. It feels like the writers of disney movies are little kids with a horrible case of ADHD that can’t think straight. Most of the female protagonists in their movies have the EXACT SAME PERSONALITY, but then they started changing that with tangeld, but now it seems they’re gonna make every female protagonist a cheerful naive character.

Didn’t like Frozen. The animtion was great, the sings wonderful. The plot was non existent. I also thought they made Hans a villain as a quick way to fill a glaring hole. All in all, I’m glad I didn’t waste my money on the DVD.

I normally love all things Disney, but you hit the nail on the head.

The real shame is that the Lloyd Alexander books are fantastic. One of my favorite series ever. There was no good reason to have this be a mess. All they had to do was make the actual book.

The Black Cauldron was too dark and scary for Disney’s children audiance (especially for that time) but it was still too soft and generic for teenaged audiance. No doubt that if it would have come out on these days things would have been different.

I like it..

I remember seeing “Black Cauldron” in the theater, I also remember being scared of it, and liking it for that exact reason. I suspect it had some subliminal influences on me, I eventually forgot all about it, considering we never had it on video (although Disney eventually released it when I was in my 20’s), until a friend reminded me about it years later. I enjoyed it the last time I saw it, but even that was well over a decade ago.

I’d like to read the books one of these days.

Just want to say I agree wholeheartedly with everything written about these Disney adaptations.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame is actually one of the only times that Disney has publicly admitted that they were wrong. An expanded staged version of the Menken/Schwartz score played for some time in Berlin (and is available, with some effort and money, as a rare import CD) and implicitly restores the tragic ending, as well as making it much clearer that the gargoyles are mental projections such that “A Guy Like You” manages to work as tragicomedy; it’s much clearer that it’s a monologue staged with four actors. An English-language adaptation just came out from Ghostlight Records, and while some plot changes were made, the tragic ending remains and indeed is made more explicit. It also eliminates the Archdeacon, restores Jehan Frollo to the story, and has Esmeralda seek shelter in a brothel rather than a farm. In the promo materials for the recording, which you can see on YouTube, there is the remarkable spectacle of Peter Schneider openly admitting that the kid-friendly story decisions in the animated version were fairly huge mistakes.

It remains fond in my memory, for the music – not only “God Help the Outcast” (which is a magnificent song), but the score as a whole.

Also, the orchestral underscore is just some great movie music. I wore out my cassette tape copy of this score (remember those?) in the late 90s.

You make very valid points all the way through this article. Could they have done a better job. Sure they could, absolutely. However, the one and most important thing you seem to be forgetting is, it’s a freakin cartoon. Who cares. The kids that it’s geared to entertain love it.

That’s all that matters.

Expecting Disney to embrace the suffering and heartache necessary to flesh out all the characters to their fullest potential is like asking a real farmer if his barnyard goose can lay you a golden egg.

Walt Disney created his first film (Snow White) to revolutionize the way the world viewed animation. Once seen as a children’s form of entertainment, cartoons were turned overnight into a style of art in the film world. Walt’s overall vision had children and adults enjoying the same things together, whether that was in amusement park attractions or animated features.

It is incredibly sad to hear so many saying otherwise, when Disney has captured the hearts of all ages for years. These films are meant to be timeless, not only to be watched on “throwback Thursday,” but to be appreciated even more when you watch them again. As a child, I adored The Lion King of its beautiful artwork, brilliant songs, and heartwarming storyline. As I watch it over as an adult, I realize just how fantasicly made this movie was. While all of the above are still true, I now can find so much more to appreciate in the movie. I can understand why it is also one of my parent’s favorite movies as well; not just because it made me happy at the time, but also because it was gripping, heartbreaking, and comical, all while having creative characters to back it all up.

Frozen does not do this. While it has moments, the overall story IS lacking and does pull out a lot of absurd stops to plug along.

I also find it extremely sad to dininish the integrity of a storyline because it is “just for kids.” Why are we watering down a plot for our future? What is there to hide in fine storytelling? Of course, there are certain themes that can be avoided, but it’s a great disservice to allow the thought into your mind that children cannot handle a good story. It should be even more important to fill the minds of our children with imagination; not a film full of crap.

The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast were for kids, but it didn’t have a crappy story. disney did it then, what’s the hold up now? Movies then were for the whole family, who mostly have to take the kids and sit through this crap. Now they seem like they are only for simple minds. And Disney hopes we’re too dumb to notice so that we can spend money on this junk.

You can say it’s for kids, but why is it getting a Golden Globe, Oscar, some adult awards, when it doesn’t deserve more than a Raspberry award?

I think that the system which worked for Walt Disney found some difficulties working when other people were at the helm.

I personally think that Frozen is just suffering from ‘overexposure’.

For me, when Hunchback of Dame came out, I thought it was gorgeous, but I never connected with any of the human characters. In fact, the only reason I ended up liking the film was because of the goat. So much so, that I actually bought ALL the goat merch! I still have the backpack and the stuffed toy with BELLS in his hooves!

I watched Frozen last July with my 11 year old cousin. Even she got sick of this movie after watching it the 2nd time. I watched this with zero expectations – and I remained unmoved emotionally even by the end of it. Such a bland movie. Even for children. Yes, even when I was younger, I KNEW what even bad kids’ movies/shows are. Take the Teletubbies for example. When I was 8, I thought it was a stupid show. Same with Barney. Ugh. It was excruciating to watch those cause it seems like adults are just insulting children’s intelligence and think they cannot be so imaginative.

This movie, though not as excruciating as those ones I mentioned, still has those problems which I have noticed in many of today’s “children’s” entertainment. I had problems with a number of unexplained matters on why the characters were what they were. Frustrating actually. This movie should have learned from, for example the Beauty and the Beast. Okay, we have the main character who turned into a beast – and even they explained it clearly why he became one in the first place.

Also, I find that there is a lot of poor characterisation in this movie. Take the last-minute villain for example. Me and my cousin snickered at the “big” reveal of this guy, Hans. It is as if the writers forgot that he was supposed to be a villain. It was supposed to shock me, right? This is how badly written the characters are. The story which this film is even driven from had a lot more plot to it and with better written characters. I’d take Gerda over Anna any day.

Highly impressed with your analysis.

Years ago, a number of friends kept telling me that I had to see Black Cauldron, that it was a hidden gem — secretly one of Disney’s best. It was dark, they said. The animation was amazing, they exclaimed.

I watched it.

What struck me was that the aspects of the movie that my friends praised were exactly the areas where I felt the movie fell flat. The animation was… not good. There was darkness in it, but also one of Disney’s worst “cutesy” characters ever, and that darkness was bland, and the characters were whiny and bratty… and why the heck should I care about them anyway?

This movie came out in a very dark (as in bad) stretch of Disney films, but even a lot of those not-great Disney films had things you could like about them. Black Cauldron? Not so much.

I’d love to see this given the kind of filming of something like LOTR, now that they have the technology to do this sort of thing in live action. Just don’t bloat it like they did The Hobbit.

Spot on. Thank you. My wife and I thought Frozen was dumbest, most boring Disney film of all time. We are most aggravated by Disney fans expounding on the courage of Elsa….WHAT? Running away from problems you never faced is courage?

So many tired, recycled story recipes, but this time done by cooks that were either totally disinterested with the taste of the meal and only focused on the presentation, or prepared in a kitchen where the chef had gone home with a headache and left his slacker, stoned assistants to finish up.

Bleh, bleh, bleh.

Bit harsh, no? Simba ran away from his problems too. I also don’t see how this could be the dumbest Disney film. Ever seen Home on the Range or Chicken Little?

The Black Cauldron is one of my guilty pleasures; I loved it as a kid for those scary, darker moments, and I still enjoy it, knowing how terrible it is.

Frozen was ALMOST the best movie ever it would have been more emotional if Olaf had died it would have made the film better

I wonder what would be different about Hunchback if they made it today. It is a GREAT story, and lends itself well to animation, just not kid-friendly animation.

If Disney was able to make a PG-13 version of this film, where the director and animators could focus on telling the story they way they wanted to, I think it would be great.

Oh no, not Black Cauldron…

I was a big fan of the books and I was so excited to see a movie version. So my friends and I went to opening weekend (we were tweens, so basically right in the demo it was aimed at).

I have never left a movie as absolutely furious as I did Black Cauldron. My friends and I hated it completely- it ruined the books, the characters, the story — I can’t remember liking a single thing about it.

In hindsight it was probably the foundation for how I treat adaptations as very much separate things from the original, but boy, was that a hard-earned lesson. I can’t say if I’d have that same reaction today (I’ve not seen the movie again, nor read the books in a long time) but I have no desire to try again, either.

I’ve never watched (or read) this story, but the title strikes me as very not intriguingly unusual. Aren’t cauldrons black by default, unless specified otherwise? It’s like saying “The Steel Sword” or “The Green Forest,” at least in this kind of setting.

I loved the books as a kid and remember being bummed out by the trailer for this film. It was clear even then that Disney ruined their chance at adapting a truly wonderful book

I complete agree with your analysis of Frozen and the other Disney adaptations. I didn’t watch Frozen until yesterday, and I gotta say I was not impressed.

The beginning felt like a series of music videos to me that’s played one after another. I thought it might be a musical, sort of, movie because it seemed to have more songs in a short span of time than the other Disney movies. And it just didn’t flow well!

They have been doing great progressive and feminist films before like Mulan (the best!) and even incorporated ideas of questioning “1-day romances” like in Enchanted. Tangled is a great feminist movie as well. I don’t understand what happened to Frozen, there’s so much potential to it. But oh well, maybe the audience doesn’t appreciate a good storyline anymore as long as they get cool effects. If it’s an award winning, billion dollar-earning movie, you gotta ask why.

I do agree with a lot of these points. In fact, I made many as I left the theatre when watching all three of these movies!

I liked Black Cauldron when I watched it for the first time. But then, I also had never heard of the Black Cauldron before it. I felt the story was interesting, so I searched for the books, read them and loved them. It was a surprise to me to read later that this movie was so shunned by people elsewhere. Different tastes, I guess. I just love a good fantasy tale.

I remember getting the VHS when it came out of the vault in my early teens and I loved it. Part of it was perhaps the novelty of it being a slightly darker film with no songs (although, I would have liked some, because I grew up on Disney musicals). But I always kind of dug the creepy vibe and I liked Eilonwy a lot. At least she was along for the ride and (kind of) doing stuff, instead of her story solely being about finding romance. And I did find their awkward romance adorkable.

Frozen is definately a sign of the current times. No one really does anything. Idle waste of time is the most common theme for most Americans. No one appreciates anything because mo one does any work to see things through. Frozen is iconic for this era in humanity in which isolation and fantasy have taken over humanity. Truely. Place an i phone or ipad in the hands of the girls. How different is it really from every day life?

Notre Dame had some great animation, some great songs, some interesting characters, but in the end, I just didn’t think it fit well together, like it didn’t really know what it wanted to be. And a lot of focus on sex and obsession, which didn’t feel like it belonged in a Disney cartoon.

I am so happy to have found an article and others that share my viewpoint. “Frozen” is a terrible movie. There are no likeable characters: the parents isolate their daughter, Elsa is mean (she sics a snowmonster on her sister, freezes an entire town, and nearly kills Anna later), Olaf the Snowman is flat, Kristoff is a goober, Hans is a very weak villian, the trolls are an odd addition, and Anna is impulsive and annoying.

The storyline is very weak because it is poorly developed and there is no real plot. Its only saving grace is the song “Let it Go” and its accompanying scene. The movie is simply a prime example of ‘herd mentality’, the hoopla will eventually dissolve, and no one will remember this movie a few years from now.

Hunchback was my favorite Disney movie when it first came out, and it remains so to this day.

Unlike Pocahontas, its adult themes (racism, misogyny, religion, public perception of disability) are given fairly nuanced treatments, and the music is absolutely fantastic. Also, much of it is so wonderfully subversive. “God Help the Outcasts” is a prime example. Esmeralda isn’t expressing faith in God, she’s challenging God to live up to the image God’s followers claim–asking why, if Jesus himself were once an outcast and if everyone is a child of God, God still lets persecution and inequality happen. Meanwhile, though she herself is not a Christian, her prayers are all for other people, whereas the prayers of the Christians around her are for themselves. It’s a gorgeous song, but there’s a lot more going on in the lyrics than people tend to remember.

And Hellfire–wow. Definitely the most daring scene Disney has ever animated, and in my view one of the best. Putting Quasimodo’s and Frollo’s contrasting reactions to their attraction to the same woman back to back was brilliant.

@terra: Agreed, very much. Does Hunchback belong in the Disney canon–a canon that has become synonymous with “safe” and child-friendly entertainment? We could argue about that for the rest of our lives and on into eternity. But I have, and will continue to, applaud it for tackling the themes you mention. For me, Hunchback feels a little like Disney 2.0–something you might watch when you’ve outgrown the cutesy stuff but aren’t quite ready for a no-holds-barred PG-13 film (or even some PG offerings; don’t get me going on the rating system). The adaptation has myriad flaws, but what works, works great.

To me Hunchback is thematically important. Consider the upswing in American fundamentalist/evangelical Christianity in the late eighties into the nineties– it is hard not to see Hunchback as responsive to that social period. As one having experienced a bout with very deep religious fundamentalism, coming of age in the eighties, Hunchback was huge. It touched something that I fully understood, entering my psyche daring to grasp those frightening themes of judgement and hell. To see Disney boldly broaching this disturbing material was surprising.

It was also deftly handled: while the evils of abusive religion are obvious, Disney doesn’t take us away from faith, but actually invites us to take refuge (sanctuary!) within it.

I’ve rarely looked at this film as a children’s story!

Only saw hunchback once in theatres. Hard to believe it’s been 20 years. Dark as it is, I still enjoyed it, especially the animation.

The Black Cauldron may not have been that good, but it was the first story to really interest me in the fantasy genre. Before seeing this I had thought fantasy was too childish to pay any heed to, and I was a child at the time. Without The Black Cauldron, I wouldn’t have ventured into Jim Henson’s movies, The Dark Crystal and The Labyrinth, which are some of my favorites of all time. Sadly I didn’t connect to fantasy novels for many more years which I regret since so many classics were being written at the time.

I was excited to see Black Coldron, and so was my young son. But we went home very disappointed. It just felt like a horrible mishmash, with a bad script, so many different artistic styles mashed together without a common vision, and a lot of just plain clumsy animation.

It’s funny, I never got a chance to see Black Cauldron when growing up, but I *did* play the computer game version — a LOT.

I remember the game both not making much sense and being crazy, crazy difficult (go figure, it was a Sierra game). The ‘correct’ way to play the game was to basically follow the plot of the story, but there are so many random occurences that really don’t make any sense, so it was very easy for a kid to not know what to do next. (I remember my friends and I wondering what the heck we were supposed to do if we saved Hen Wen? What was the point of Gurgi? etc) I always thought this confusion was the result of purely bad game design, but now I’m wondering if it’s partly because of the disjointed movie it’s based on.

That said, I think I should read the book in any case.

I played the Sierra game as well. I remember using the cheat book an awful lot. When I saw the movie as a kid, I actually liked it. It just looked so different and there was something I actually liked about Gurgi… When I saw it again as an adult, I thought it was interesting in that it was an attempt that Disney to make something that really wasn’t happening a lot in American animation at the time, darker animation for kids. There might have been other companies trying that as well, but surely none as big as Disney.

Two books into the series, it actually makes the movie harder to watch because you can see just how wrong it is. The books are just so so so enjoyable and the movie has so much going on that it seems to forget the great mixture of humor, heroism, and morality that the books have.

Oh man, I miss those old Sierra games. I am so going home to put an emulator on my computer. 🙂

I saw the Black Cauldron as a kid after I read the books (thanks to my mom’s insistence). As a result, I was extremely disappointed in the movie. I remember being horrified when Gurgi died and indignant when he returned to life. I still think that element undermines the theme, even if it makes the story end more happily.

Now, I think I should watch the film again. I enjoy different things about movies as an adult, and I remember the look of it made an impression on me.

Thanks for the article!

It’s almost as if Disney completely changed the course of the film after they heard “Let It Go” for the first time and knew it would be the hit song of the film. Thanks for the insight on the story behind Frozen.

Honestly, this piece sums up everything about Disney’s sloppy way of handling adaptations and dark storylines. Darkness without any justification for said darkness is a tired trope and I’m glad that someone has finally addressed this in such a thorough manner.

I love how you summed up Disney’s biggest pitfall: “darkness without any justification for…darkness.” If you do something just for the sake of doing it, you will screw it up. With dark, heavy themes in particular, you have to be careful. For instance, Pinocchio is considered pretty darn dark by today’s standards, because of the adult fear associated with it (your kids suddenly go missing, are turned into animals, and sold off to who knows where. And by the way, Lord knows what that coachman is doing with the boys who can still speak). But mainly, Pinocchio leaves us only with the *suggestions* of what could happen under such circumstances. It works because our imaginations fill in the gaps–and the human mind can get rather sinister.

On the other hand, more explicit dark themes, such as those found in Hunchback, don’t always work. If anything they, as noted, can fall flat. With Hunchback, Disney went too far. It overestimated how much the audience should be explicitly exposed to and left nothing to the imagination. Thus, what you get is a movie that’s too scary for the target audience. It’s disturbing to adults, but not on a level that says, “Wow, that shook me up.” Rather, adults are disturbed because, “How dare Disney market this to my kids; I have to censor it.” And once creativity crosses that line, it’s often dead in the water. For darkness to work, it must always serve a purpose–and its creators must employ a level of self-control.

Good way to define Disney and its adaptations.

Awesome

Fantastic article!!

The Prydain books are among my favourite, and still good to return to as an adult. I read somewhere that they are being looked at again by Disney. I hope so! The market is ripe for them to be adapted with proper budget and investment. Look at the oomph they are throwing behind A Wrinkle in Time that they just filmed here in New Zealand. If they put that kind of effort into Prydain, we could have a very good fantasy series of movies!

In 1991 when I was 12 and infatuated with The Little Mermaid, I wrote to the Walt Disney Studios and begged them to animate The Snow Queen, my favourite Andersen tale. So, you’re welcome.

I struggled with Frozen the first time, sorrowful that I found none of the elements that would have told me I was watching The Snow Queen, at least in some shape or form. Gone was the mirror, the shards and the abduction. No more terrifying snow goddess. Witch of the Summer Garden, robbers and royals… Lapp Woman, all goodbye. Ultimately, I fell in love with the character of Elsa, even though I hate Olaf and all such cartoony elements in the movie.

Again, great article – thanks!

I loved The Hunchback of Notre Dame, precisely because of its darker tone and more controversial villain. Follo is remorseless in his treatment of Quasimodo, considering him an abomination, and uses his priestly influence to justify his sins and atrocities committed against Esmeralda. The emotional connection the audience feels to Quasimodo for his diversity against societal norms and the feeling that Esmeralda may be the only person to accept Quasimodo for who he is inside, regardless of his appearance, only makes Frollo’s ultimate evil ambition and the gothic, creepy overtures all the more chilling.

I believe Disney has struggled to find an ideal balance between light-hearted fantasy and gritty adventures. The Secret of Nimh (Don Bluth’s masterpiece before the disgusting travesty that was its sequel) worked so well as a darker cartoon theme because the entire world was designed to present itself as threatening, enticing and surreal. Disney needs to take cues from Don, and craft perhaps a Hunchback sequel, or another movie dealing with darker themes. Sometimes, a break in the traditional light-hearted fare is refreshing and brings innovation to an otherwise stale formula of scriptwriting and character dynamics.

It’s difficult to reconcile the success of ‘Frozen’ with the numerous missed opportunities you outlined in this discussion of adapting ‘The Snow Queen’. I think it’s unfortunate that the film owes it’s popularity to excessive marketing and an almost solely profit-driven goal.

Insightful and interesting article! These adaptations run the gamut from well, that could’ve been done better (Hunchback, Pocahontas, Black Cauldron) to, what in heaven’s name were they THINKING (arguably, Hunchback again, plus that adaptation of Anne Frank. Because really, Disney? FREAKING ANNE FRANK)? Some stories are just not meant to be Disney-fied!

Ahem.

I happen to be a pretty big Hunchback fan, so I’m inclined to give the adaptation a pass, but of all the films mentioned here, I definitely see its problems. Even if you left out the obvious pitfalls, such as discussions of Frollo’s sexual attraction to Esmeralda, Victor Hugo is notoriously tough to read, let alone adapt. Plus, most of the original novel’s themes and events just don’t lend themselves to Disney, which is why, as is rightly said, Disney can’t commit to Frollo as an antagonist.

With that being said, I would be disappointed if Disney didn’t keep trying to explore “grown-up” themes in its films. I have described Hunchback as Disney 2.0–that is, Disney for an older and more mature audience made up of kids who, while still innocent, are ready to start asking and discussing bigger questions about bigger issues. Hunchback, then, serves a purpose in the canon, even if the delivery is clunky. Pocahontas could have been another example of this, if the producers and director hadn’t butchered history (but then, university historians do that too, so…) Anyway, all that to say I would love to see Disney “dig a little deeper,” as Mama Odie would put it. I just think they’re so scared of losing the youngest members of their audience, they feel they can’t do so successfully.

A great discussion, too often Disney slides by on its name alone and a catchy song, but we often need to look deeper at what these films are actually saying about our society and the future generations they are supposedly trying to inspire. I think the issue of Disneyfication needs to be further discussed and condemned, either respect the story for what it really is or let someone else better suited tell it.

I feel like I’m the only person who ever has anything positive to say about the gargoyles in Hunchback. I think the article makes some great points about Disney and their shortcomings in adapting, and admittedly it really doesn’t touch on the gargoyles. But I actually think the gargoyles add to the overall Hunchback story BECAUSE they offer lighthearted fare in the midst of the darkness; after all, it may be a kids film with mature and heavy themes, but it’s still a kids movie. Might we have a more interesting package if the comedy had been cut? Probably. But I think we’ve seen with The Black Cauldron that that’s not something Disney is especially good at in their animation (at least not historically), and without some lightheartedness I don’t think the film would be remembered as fondly as it is today. To quote, of all things, Fraiser: “What is the one thing better than an exquisite meal? An exquisite meal with one tiny flaw we can pick at all night.”

Frozen may have been going for a deeper message with the sympathetic treatment of Elsa, but it got lost with the focus on the Rapunzel recreation attempt of Anna’s character. Elsa works as a combined Kay/Snow Queen character, with a metaphorical frozen heart to Anna’s (Gerda’s) physical one . If you view “Let it Go” as Elsa shutting people out in her attempt to achieve freedom, she is freezing her heart and disavowing the good she is leaving behind as well. We see this again when she pushes Anna away. In the end, Anna is frozen and Elsa’s tears allow both of them to thaw as she expresses love and grief. The focus on Anna makes this less clear. Tangled did a better job mixing light/dark themes and character development while still making a coherent and enjoyable story, though frozen had better music.

Great analysis! And this only scratches the surface of Disney’s moral dubiousness.