Disney Protagonists and the Seven Deadly Sins

When most of us think of protagonists from media, we don’t think of them as sinning. The very definition of “protagonist” is “the leading character or one of the main characters in a…fictional text,” the one we are meant to support. Colloquially, protagonists are thought of as “the good guys,” antonyms of antagonists and villains. Protagonists are human, or humanlike, and thus flawed. But media consumers usually expect protagonists’ moral compasses to point due north. If that compass slips and stays out of place too long, consumers feel let down.

This is no truer for any protagonists than those in Disney. Walt Disney’s pantheon of heroes and heroines are protagonists viewers support from earliest years. They offer plenty of good traits to emulate–kindness, courage, tenacity, patience, and loyalty, to name just a few. However, Disney fans who start out as children grow up to be teens and adults, and as they grow, they often find their heroes are more flawed, and yes sinful, than they looked on first, second, or even tenth viewing.

Across social media, one can find plenty of Disney fans discussing the less-than-savory traits of Disney heroes and heroines. Some of these are related to the time periods in which certain films were made. Snow White and Cinderella, for instance, are routinely maligned for passivity and accused of being overly dependent on men, specifically their princes. Other criticisms are related to the worldview characters hold vs. the real world Disney fans interact in. John Smith, for example, has received heavy and continuous backlash in the almost 30 years since Pocahontas premiered, since he spends 90% of the film calling its star and her people “savages” or “savage Indians.”

No matter what time period a viewer is in or what worldview they hold though, they will find “innocent” Disney characters can commit sins like any other person (or humanlike creature) in media. This is a new look at Disney heroes and heroines that proves they are more relatable than they might appear. It gives viewers the opportunity to keep learning from them long after those viewers have “outgrown” Disney. It may provide some sense of moral relief, as viewers acknowledge these sins and recognize yes, it is good to emulate protagonists’ positive traits. Yet failing to do so is less a permanent blight than an opportunity to examine what went wrong and try to improve.

This discussion will examine several Disney protagonists’ relationships with the Seven Deadly Sins. These sins, in no particular order, are: pride, envy, wrath, greed, lust, gluttony, and sloth. They are most commonly associated with the Roman Catholic Church, though other branches of Christianity acknowledge them as well. This is not an attempt to privilege Christianity’s teachings. Although other religions may have different terms for these sins, most of them agree that in whatever form, they lead to negative behavior and consequences. The Christian or Jew who warns against gluttony at the Christmas or Hanukkah table can find much in common with the Muslim who avoids gluttony partially through fasting on occasions like Ramadan, or the Buddhist who fasts as part of reaching Nirvana. Rather, the Seven Deadly Sins are used because they have been named and numbered, are easily recognizable in their list form, and would be recognizable as “markers” for sin for most Disney protagonists.

Each deadly sin will receive a pair of Disney protagonists who commit it, a male and a female. Some protagonists may not be human. This is an attempt to show sin is no respecter of gender, position, or other traits. Sin is a great equalizer. Anyone can be tempted and anyone can fall. The pairings are also an attempt to keep certain protagonists from looking more sinful than others.

The “Big Four”: Pride, Envy, Wrath, and Greed

Since there are seven deadly sins and fourteen protagonists, the sins should be divided up. There is an odd number, so splitting the sins by order of “importance” or “rank” would not be accurate. However, the sins can be separated based on where they originate and the effects they have on the protagonists.

The deadly sins fit into two distinct camps. Pride, envy, wrath, and greed fit into one camp and originate from the human ego. “Ego” usually connotes pride, and pride and ego work closely together. But here, “ego” refers to self-perception, self-preservation, and self-gratification. The four sins in the first camp originate when we don’t get whatever feeds our ego. Some churches refer to these as “sins of the spirit,” or “attitude sins,” as opposed to “action sins” of gluttony, sloth, and lust (Van Gelderen 2019). Because of these sins’ direct connection to the human ego and heart, we’ll call them “the big four,” although no one sin is actually “worse” than any other.

The first eight protagonists each had a problem with one of the “big four” sins. Keep in mind, none of them took their sins to villainous levels. They are still heroes. Their desire and ability to break these sinful behaviors only makes them stronger and worthy of discussion. Additionally, no protagonist’s personal characteristics–gender, origin, color, creed, ability level, or otherwise–makes him or her more or less vulnerable to a sin. Nor are these ever the cause of deadly sins, though they may play a role in why actions that become sinful start out as justifiable.

Pride: Belle and Woody

Pride is often considered the gateway to the six other deadly sins, or the “father” of all the others. Many Christians point to Lucifer, later Satan, as an example of why this is. Formerly the most beautiful of all angels, Lucifer’s pride led him to seek God’s power, and take a third of Heaven’s angels down with him.

PursueGOD.org defines this sin as “the refusal to recognize and admit the presence, equality, or even superiority of any other being.” It is “a false pathway to self-worth,” and can become inverted in false humility. That is, an excessively prideful person can believe the antidote to his or her problem is self-hatred, which then becomes a form of pride in how humble and self-effacing he or she has become. As C.S. Lewis wrote in The Screwtape Letters, if a demon can get a human to think, “By Jove, I’m being humble,” and take pride in that, the human is still committing a deadly sin and the demon has won the battle against said human’s Godlier instincts.

Pride can also be “a false belief in one’s own abilities, that interferes with…recognition of the grace of God.” Disney characters do not acknowledge God as such, certainly not a particular deity. But the prideful characters do fail to recognize there are “higher” and morally superior forces around them, or benevolent forces who know better than they do what they need and how they should live. They also fail to recognize the equality and worth of others.

Two of the most prideful protagonists in the Disney animated canon are Disney princess Belle, and Pixar hero Woody. These two have every reason to indulge their egos. Well before becoming a princess, Belle is widely known as the most beautiful girl in her French village. Plus, she’s brilliant, one of the only literate citizens in town according to the 2017 Beauty and the Beast remake, and less shallow than other girls her age. She is “the total package.”

For his part, Woody is literally set up for pride. He’s the beloved favorite toy of his six-year-old owner Andy and thus, leader of the entire roomful of toys. He’s proven himself a benevolent leader, such that Andy’s army men–a literal bucket of military personnel–take his orders rather than stick to their own hierarchy. Woody’s characterization is a sheriff, a law enforcement officer whose position automatically commands respect. To top it off, according to Toy Story franchise director Lee Unkrich, “his actual full name is Woody Pride” (Twitter). Until the events of Toy Story, Woody has rarely if ever seen the inside of Andy’s toy box like a “regular” toy, or spent time on the floor or a shelf. He leads and rules from “his spot” on Andy’s bed and sleeps with him every night, set up as the favorite and never allowed to forget it.

Neither Belle nor Woody are fully conscious of their prideful tendencies. Viewers can’t call them arrogant, as they would a villain, because neither purposely or constantly uses pride to bully or berate. But as any person will when tested, both princess and sheriff give in to at least some of their more sinful instincts. Yielding lands them in trouble, some situations more severely than others. But what they learn from those situations makes them more legitimately humble, circumspect, and more heroic people.

Belle: Princess of Pride

Viewers see Belle giving in to ego a bit before the conflicts of Beauty and the Beast test her mettle. Adult Disney fans often malign her as a snob, pointing to her introductory song where she laments the monotony of her “poor provincial town.” She “wants much more than this provincial life,” and viewers can’t blame her, considering her neighbors call her “a beautiful but funny girl,” “nothing like the rest of us,” and “odd.” Some take their gossip and speculation further, claiming Belle is “crazy” like her allegedly unstable father, Maurice. In the remake, the townspeople assume Belle believes she is above them because she can read, loves to do so, and teaches village children.

One could argue that Belle’s pride, if it exists, is a defense mechanism. After all, everyone except her immediate family and the bookseller backhandedly compliments, insults, or gossips about her. No one makes any effort to get to know her or come into her world. Since most of the townspeople are adults, one assumes they could choose to learn to read or discuss books or Belle’s other observations with her, but would rather speculate and pout.

The problem is, such friendship requires reciprocity, and Belle is either unable or unwilling to reciprocate. Her constant desire for something “more than provincial life” comes across as judgment against her neighbors. It doesn’t help her case that she barely says more than “bonjour” when walking through town, even to children (she pats one’s head in the animated version and then keeps walking and reading, right through a jump rope game). Viewers are left to assume she does this every day. Belle complains and feels sorry for herself but doesn’t interact and doesn’t consider whether she could make an effort to change.

These instances of ego are fairly easy to forgive, considering we immediately see Belle showing support and compassion for her dad, and putting off Gaston, whose own ego has completely taken over and who deserves to be exposed as an antagonist. It’s not until Belle actually gets the “more” out of life that she wants, and has to handle the consequences, that viewers get to see her recognize her attitude, learn from it, and grow. Belle gets the opportunity to live in an enchanted castle and gains allies who treat her with compassion, understanding, and friendly curiosity. But this only happens after she becomes the Beast’s prisoner, and agrees the arrangement is permanent. Belle has traded the comfort of home and the security of her father’s love for a nebulous ideal, based on the subconscious belief that what she had wasn’t good enough.

Prisoner of a Beastly Ego

Belle’s ego continues blocking growth as she adjusts to life with the Beast. In the Broadway musical, she clings to false humility at first, singing, “I don’t deserve to lose my freedom in this way, you monster!” Yes, the Beast is a monster, with an explosive temper and selfishness to rival the most spoiled and pampered of royalty. Yes, he views Belle as less than human. But viewers may wonder, why does Belle think she doesn’t deserve to lose her freedom? She admits she made the choice of her own free will (Beauty and the Beast track 7). Moreover, the word “deserve” indicates Belle may think she’s too good for trials to befall her. Again, she doesn’t consciously mean this. But she has always been considered beautiful and brilliant, an ideal person. More importantly, she has chosen to spend her time and energy with people like her father and the bookseller–fellow outcasts–and with books and deep thoughts rather than shallow pursuits like suitor-chasing. Therefore, Belle’s first reaction to captivity leans on false humility.

As the Beast pushes Belle to her limits, her mask slips off. When the Beast forbids her to eat dinner because she refused to join him, Belle will not consider his point of view. “Why don’t you give him a chance?” the wardrobe Madame La Bouche asks. She might be excusing her master’s beastly behavior, but on the other hand, La Bouche has known the Beast for more than 11 years. She’s probably aware that, given time to calm down, he might reopen the conversation and treat Belle more civilly. But Belle isn’t ready to give the Beast a second chance. “I don’t want to have anything to do with him!” she exclaims. Mere hours later, after flouting explicit instructions not to enter the castle’s west wing, she declares, “Promise or no promise, I can’t stay here another minute!”

Again, Belle’s behavior is understandable. But it is not necessarily excusable. Part of the trouble she’s in happened because she disregarded explicit and reasonable instructions–the castle is home, but do not enter this one area. In entering the west wing then, Belle yielded to her ego more easily and dangerously than any other time in her story. One can hear echoes of Genesis 3, when God gave Adam and Eve the entire Garden of Eden to partake in except one tree–the tree from which they, out of conviction they knew better, chose to eat. Additionally, note how Belle speaks to Madame La Bouche and the other servants. “I don’t want anything to do with him,” “I can’t stay here.” She has no concept of those around her. Every statement is an “I” statement. Belle is wholly focused on how she feels, how the situation affects her, and what she can do to keep herself safe. Again, it’s understandable, but it disregards the presence and equality of the servants, who have been nothing but kind. Belle treats them as guilty by association.

Unlocking True Humility and Her Crown

Fortunately for Belle, she’s open to change. The impetus for that change takes the form of danger. When Belle runs away, a pack of wolves attack her. To her credit, she tries to fight them off and does fairly well for a teenage girl armed with nothing but a large, sharp stick. But it is the Beast who comes out of nowhere to save her life, sustaining severe injury and unconsciousness in the process. Belle immediately loads him onto her horse and leads the way back to the castle, giving up her comfort and risking severe cold exposure since she has neither the Beast’s fur nor his more adequate winter clothing and shoes. Later, she offers him a sincere “thank you” and tends his wounds despite the Beast’s pain-fueled outbursts.

The wolf incident marks a turning point for Belle, not only in understanding the Beast but dismantling her prideful tendencies. Remember, the sin of pride involves failure to recognize presence, equality, and sometimes superiority of other beings. Here, Belle has recognized all three in the Beast. She understands he is present and deserves recognition as a housemate if not superior (in the sense that he has been treating her as a prisoner and subordinate, which takes advantage of her). She understands the Beast is her equal, in that both are in pain and need compassion. Most important, Belle now recognizes the Beast can be a good person, and in some cases superior. Had he not been willing to save her life, Belle would have died, from exposure if not the wolf attack. In this case, Belle acknowledges superiority is a sign of strength she doesn’t possess.

Belle continues this trajectory throughout Beauty and the Beast’s second half. Over time, she relates to Beast more and more as an equal human. For instance, she’s at first shocked when she sees the Beast diving into a bowl of soup face first. But whereas before, Belle would’ve acted disgusted, she smiles in understanding. When she sees Beast’s paw makes spoon usage prohibitive, she compromises. She tilts her bowl toward him, indicating they can neatly drink their soup instead. Later, she’s thrilled over the Beast’s gift of his library. “It’s wonderful…thank you so much,” she says, in a tone near jubilant tears. Viewers are reminded, no one has ever responded to Belle’s deepest interests this way before. Even though her father clearly loves her, he probably couldn’t have afforded to indulge her the way he wanted or felt she deserved. Therefore, the Beast’s gift becomes an act of material love and an act that says, “I see you. I see what brings you joy, and I see that your good heart means you deserve more joy in your life.”

However, it is not until the film’s climax that Belle unlocks the final piece of true humility. This happens in two pieces. The first occurs when she opens up to Beast, revealing a vulnerability she had kept guarded even as their love blossomed. “I miss [my father] so much,” she admits. She then pleads to see him “just for a moment.” It’s an act of self-lowering–we have never seen the self-assured Belle plead for anything. But the Beast immediately responds, and when his magic mirror shows Belle Maurice is ill and stumbling through the forest alone, Beast doesn’t hesitate to release Belle from her imprisonment, at great emotional and personal risk. Once again, Belle shows gratitude–“Thank you for understanding how much he needs me.” Viewers who have “kept score” will notice how much she has leaned on gratitude during the film’s second half. They may also notice her exact statement–“thank you…he needs me.” The situation is not about Belle anymore. Here, she has made a truly selfless choice. She gives up love, understanding, and companionship for the sake of someone else. She also humbles herself in that she risks returning to the isolation and shunning of her village.

Belle nurses Maurice back to health and does her best to keep villainous Gaston and his mob from going after Beast with murder on their minds. Even locked inside an insane asylum’s transport, her first concern is for Beast and the castle denizens, not herself. But it is not until she finds Beast dying on the castle roof that she makes the ultimate move toward humility. In full view of the castle’s servants–“public”–she cries, allowing herself to lose control. She again lowers herself, physically and emotionally, pleading, “Please don’t leave me. I love you.” That last statement breaks Belle’s pridefulness for good. It communicates not only her ability to put others first, but her ability to act out of the highest virtue, love. Everything she has done for Beast is out of sacrificial love for him. As 1 Corinthians 13 says, Belle has learned love’s patience, kindness, and lack of pride and self-seeking behavior. She has lavished it on others, as a princess must lavish it on her kingdom. Though Belle always acted with the acumen, elegance, and wit of a princess, she has now grown into the wisdom, compassion, and true selflessness a monarch also needs.

Woody: A Law Unto Himself

Unlike Belle, Woody Pride of the Toy Story franchise doesn’t start out looking egotistical. He presents as a natural, and good, leader. Viewers could argue he never asked to be a leader. If anything, Woody has one up on Belle because he has already chosen a humble path when Toy Story begins. He could’ve been a tyrant.

Instead, the other toys are Woody’s friends and his team. When “the coast is clear” and the toys can come alive, everyone is eager to spend time with him. Woody encourages Rex while the latter practices his lackluster roar–“I was close to being scared that time.” He compliments Etch-a-Sketch when the two engage in “gunplay”–“Etch, you’ve been workin’ on it…fastest knobs in the West, huh?” He assures girlfriend Bo Peep he’ll steal away later for a romantic moment, and treats Slinky as a checkers buddy, confidant, and second-in-command. When Andy’s birthday party is announced a week early due to an impending move, Woody urges the other toys not to panic and reminds them their first priority is being “here for Andy when he needs us [not] how much we’re played with.” Having said that, he does let Sarge and the Army men “establish a recon post.”

As with Belle, Woody’s first indicators of pride are not only understandable, but perhaps excusable. When Sarge announces Andy has received innocuous birthday presents, the toys think they’re off the hook. But then Mom pulls out her surprise present–Buzz Lightyear, the newest and coolest toy on the block. Astronaut Buzz has everything–wrist communicators, karate-chop action, a working helmet, a laser, and “space wings.” He outstrips Woody in the one area the latter could compete; Buzz’ voice box is technologically advanced, clearer, and has more phrases. As Mr. Potato Head observes, Woody only has a pull string that “sounds like a car ran over it.”

All the toys are impressed with Buzz, fawning over all his accoutrements and asking questions like, “Man, the dolls must really go for you, can you teach me that?” Rex buys into the idea that Buzz is an actual Space Ranger, asking what the job entails. Slinky gives an impressed, “Golly bob howdy!” These are toys that just about an hour ago, were distraught over the idea of anybody new shaking up the status quo. Now they have pushed Woody out of their interactions. They’re not only welcoming Buzz, which Woody encouraged. Woody is justifiably upset because his friends are elevating Buzz to a position he didn’t earn and a Space Ranger identity that isn’t real.

Above the Law, Ready to Fall

If Woody’s pique stopped there, he wouldn’t be guilty of a deadly sin. He could have gone to Buzz in private and expressed his feelings. Instead, he stews and engages in actions that prove this sheriff thinks he’s above toy law. In a montage, he refuses to participate in daily room activities like exercise and play because Buzz is leading them. He shoves Slinky off the bed while Buzz pets and grooms him. He also threatens and mocks Buzz, saying things like, “You stay away from Andy. He’s mine,” and, “You actually think you’re the real Buzz Lightyear?”

At this point, like Belle, Woody’s pride crosses from the understandable to the sinful. He won’t recognize Buzz’ potential as an equal or his strengths. Worse, Woody won’t recognize Buzz’ presence, as a potential co-leader or otherwise. He doesn’t want Buzz in the same room, which sets him up for a fall.

After a long day of packing, Mom treats Andy to dinner at Pizza Planet, and tells him he can bring one toy. Woody uses the last of his patience to leave Andy’s picking him up to chance. But when the Magic 8 Ball predicts “don’t count on it,” he engineers a plan to knock Buzz behind the desk and out of Andy’s sight, so Woody will be his default choice. For all his scheming, Woody doesn’t calculate the swing of Andy’s gooseneck lamp. It propels Buzz out the window, and possibly into the yard of Sid, the toy-torturing kid who lives next door. The other toys deduce Woody pushed Buzz and refuse to believe it was an accident, calling for his “blood.” Andy does choose Woody to go to Pizza Planet, but the victory is hollow.

When Woody finds Buzz has hoisted himself into Mom’s van, the latter is in no way ready to make up. Actually, Woody lets his ego win again when the two get into a fight in a gas station parking lot. Begrudging cooperation lets them hitch a ride on a Pizza Planet delivery truck, but getting back to Andy will be fraught with obstacles that will push Woody’s ego to its limit.

Through some bizarre coincidences–or perhaps the toy universe’s version of Providence–Woody and Buzz end up stuck in a claw machine. Toy-mutilating Sid wins them as “double prizes” and takes them home to “play.” True to his vice, Woody’s first concern is for himself–“We are gonna die. I’m outta here!” The only reason he doesn’t leave Buzz to rot is because he knows if he shows up in Andy’s room without Buzz, he might face a fate worse than Sid. This compounds Woody’s selfishness, in that he’s only using Buzz to win back favor and position, and has no compassion for another toy who might be frightened and confused. No matter that Buzz isn’t acting that way; it’s jarring to see Woody, who once treated fellow toys with respect, react so callously to shared travail.

Falling With Style, Earning His Tin Star

Woody continues feeding his ego the longer he and Buzz are trapped in Sid’s room. He assumes Sid’s other toys are cannibals because they are ugly, pieced-together, or random collections of parts, and because he saw them “slurp” another toy under Sid’s bed. He doesn’t consider they were protecting that toy. Later, when Buzz is depressed over finding out he really is just a toy–and a non-flying one at that–Woody is unsupportive. He only pretends he and Buzz are friends so Andy’s toys, communicating from the opposite window, will be willing to welcome him back to Andy’s room.

When the other toys discover Woody was using Buzz’ unattached arm as a stand-in for him, they assume Woody has finally “killed” Buzz and cut off communication. Woody is crushed. Yet he still isn’t ready to take ownership in his situation until Sid puts his master plot into action. Sid has finally received “The Big One,” the crown jewel in his collection of explosive rockets. Spotting Buzz amid the carnage of his room, he declares, “I’ve always wanted to put a spaceman into orbit.” Sid straps Buzz to the rocket, prepared to blow him up that minute. Fortunately, a downpour delays the launch, and Buzz and Woody share a night as toy “death row inmates,” so to speak.

At this point, Woody begins understanding Buzz’ depression and hopelessness is real. He urges Buzz not to give up–“C’mon, get up here and get this toolbox off me…I’ll get that rocket off you and we’ll make a break for Andy’s house!” Buzz, however, has reached rock bottom, ready to “die.” When Woody says he’s not thinking clearly, Buzz counters, “No…you were right all along, I’m…a stupid little insignificant toy.”

The Woody viewers have seen through most of the film would gloat at hearing Buzz admit his toy status. But our sheriff has finally gotten still and quiet enough to think through his own flaws and learn some valuable lessons, which he shares with Buzz. “Over in that house is a kid who thinks you’re the greatest, and it’s not because you’re a Space Ranger, Pal. It’s because…you are his toy,” Woody says. He extols Buzz’ coolness, the features and accessories he once mocked, and admits, “What chance does a toy like me have against a Buzz Lightyear action figure? Why would Andy ever wanna play with me when he’s got you?”

Unlike with Belle, this doesn’t read as false humility. This is Woody admitting he is not the coolest toy around and is capable of being less than the favorite. While it’s difficult for viewers to see Woody so down on himself–remember, he is a good-hearted toy with a lot of love and leadership to give–his words indicate he recognizes Buzz’ presence, equality, and superiority in the sense of needed strength.

Perhaps it’s this honesty, and not Woody’s pep talk, that Buzz needs to pull himself out of his slump. “C’mon, Sheriff, there’s a kid over in that house who needs us,” he reminds Woody. By unspoken agreement, the two cement their friendship and launch their escape, only for Sid to wake and remember it’s launch day. He grabs Buzz and carries him to certain doom, giving Woody time to gather the toys he once shunned and engineer a full-scale rescue mission. “If [this] works, it’ll help everybody,” he promises, underlining his new commitment to putting other toys first.

The rescue mission–full of intimidating voice box work, toys rising from the earth, and zombie-like movements–goes off beautifully. And when Woody accidentally lights the rocket Buzz was strapped to, forgetting that rockets explode, Buzz holds his friend up while using his space wings as leverage to disengage from the rocket and keep them airborne. “This is falling with style!” he exclaims when Woody exults that Buzz is flying, giving a nod to Buzz’ own lessons regarding ego. When both toys hit Andy’s box of favorite things in the back of Mom’s minivan and Andy is joyfully reunited with them at last, their new friendship and humility toward each other make the ending that much sweeter.

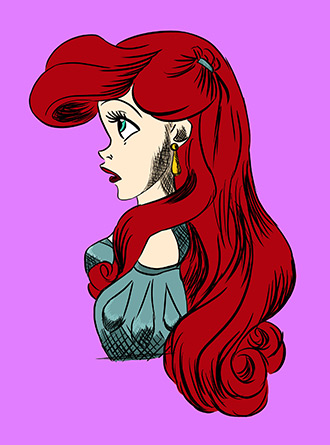

Envy: Ariel and Wreck-it Ralph

The next deadly sin is envy. Envy closely relates to pride, involving a desire for what others have, which feeds the ego of the one who desires. But envy is its own deadly sin and causes its own consequences. Universal Life Church defines it as “the desire to have a quality, possession, or other desirable attribute belonging to someone else.” Christianity.com calls the Biblical definition of envy, “[The] sin of jealousy over the blessings and achievements of others.” Merriam-Webster’s dictionary points out envy can be different from ordinary jealousy in that it involves “painful or resentful awareness” of other people’s real or perceived advantages that you don’t have, and a consuming desire to gain those.

Out of the Disney heroic canon, the two most envious protagonists are Ariel and Wreck-it Ralph. Both have understandable reasons for envy, and were arguably set up in-story to experience it. Ariel is a mermaid princess who has everything she could ever want under the sea. Still, she envies humans and their world, lamenting over her desire to be part of it, to the point of getting herself in irreversible trouble. Without a major plot twist, Ariel’s deadly sin might have taken her down for good.

Wreck-it Ralph is not royalty, and unlike Ariel, he doesn’t have a powerful or desired position in his world of video games. Therefore, he’s more set up for envy because he has a lot more to desire and more to lose. Like Ariel, Ralph isn’t conscious of his envy or the sinful way he handles it. Nor does either protagonist hurt anyone on purpose in their quest to handle envy. But when the green-eyed monster gets its claws into Ralph and Ariel, they’ll have to fight for gratitude in order to disengage.

Ariel: “I Want More”

The desire for “more” is the first thing viewers learn about Ariel’s character when they watch The Little Mermaid. When viewers meet her, Ariel is exploring a sunken ship in search of lost human treasure. Ariel’s desire goes much deeper than treasure, though. When she expresses a desire for more, she means, more of the world as she knows it and what might be beyond what she knows. She means more of the intangibles–more experiences, more independence, more knowledge, more friends, more room to grow.

None of these desires are sinful. They are natural and, if tempered with virtue, good and right. In Ariel’s case, they are understandable, too. Ariel is a princess and thus, privileged in her world. But with that privilege comes royal obligation and heavy sheltering. Ariel is expected to go where she’s told, stand or sit where she’s told, sing or speak when she’s told. If she doesn’t, it reflects badly on her father King Triton, the royal court, and the kingdom of Atlantica, as we see when she fails to show up for a concert at which she was the featured soloist. Sebastian’s muttered comment about Ariel needing to “show up for rehearsals once in a while” indicates this wasn’t the first time she’s been late or absent.

As for the sheltering part, Ariel is overprotected, almost to the point of stifling. Triton forbids Ariel to go to the surface, for fear humans will see her and she will be “snared by some fish-eater’s hook.” This is reasonable, as is Triton’s frustration at Ariel’s disobedience. It’s particularly understandable once viewers know, from prequel Ariel’s Beginning that our princess is most similar in looks and personality to her mother Athena, whom pirates murdered. But Triton’s stern response, plus his refusal to listen to why Ariel is so fascinated with the human world, feeds Ariel’s envy and tendency to rebel.

All this said, it would be incorrect to blame Triton for Ariel’s behavior. She is sixteen years old, and while she’s still a child, she is more than old enough to take responsibility for her actions. Granted, she may not realize the full impact of those actions. Psychology tells us the human (or mermaid) brain isn’t fully developed until the age of 25, and teenagers in particular have a hard time regulating their emotions. Ariel has about a decade to go before we could consider her a “responsible adult.” But like fellow princess Belle, she’s ready to face her flaws and the consequences thereof. Plus, because Ariel is more impulsive than Belle and wears her envy of the human world on her sleeve–er, fin–her journey toward virtue becomes more overt.

Vexed and Voiceless

The more Ariel desires to learn about the human world, the more Triton, Sebastian, and “wiser” voices push back. These older and wiser influences mean to quell her covetousness. But in a dark example of reverse psychology, the more these voices, Triton in particular, tell Ariel to ignore the human world, the more she longs for it. Each time she sates her longing a little bit–say, with a human object–the more painful and resentment-filled her envy becomes.

Envy is a deadly sin largely because of its resentment component, and by The Little Mermaid’s halfway point, Ariel has plenty of resentment to spare. Her solo “Part of Your World” drips with it, as she sings about a desire to pay a great price to “spend a day warm on the sand,” and stop being reprimanded and stifled. She’s “sick of swimming” and laments, “When’s it my turn?”

If Ariel had stopped at resentment, there would be hope for her envy to be stopped. She and Triton might’ve come to a healthy compromise. But when he discovers Ariel’s secret grotto of human treasures, including a statue of Prince Eric, Triton loses his temper. He destroys Ariel’s treasures in a rage, leaving her in the grip of desperate heartbreak and full resentment.

Ariel’s envy of the human world still stands, but once Triton destroys her treasures, she experiences a new level of it. She goes from a painful but nebulous envy of the human world itself, to a concrete, excruciating envy based on the love and freedom she believes she can only find there. Ariel believes she has lost all hope of love, freedom, and understanding in her own world. Therefore, she must get these things from humans, specifically Eric, to be happy. Never mind the human world is unknown, humans could still be dangerous, and she and Eric have never so much as said “hello.”

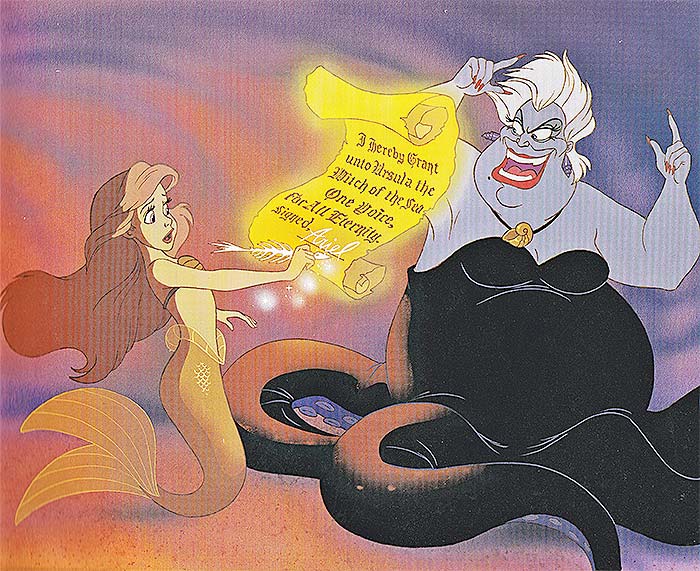

Ariel’s envy, combined with her heartbreak, leads her into the grasp of sea witch Ursula, who gives her the sympathy she needs. Note though, that Ursula’s sympathy isn’t constructive. That is, Ursula doesn’t sympathize with Ariel as a young girl who may not know what she’s asking for, but has real emotions under the surface.

True to her villainous nature, Ursula uses her own, more unchecked, deadly sins to capitalize on Ariel’s envy. She feeds the envy, saying things like, “[Eric] is quite a catch, isn’t he,” and telling Ariel that even if she became human and never saw her family again, “You’ll have your man.” In other words, “You’ll give up what you have, but you’ll have what you want.” Ursula makes Ariel into a victim, not only of her own sins but of others’ real and perceived ones, calling her a “poor unfortunate soul” and saying she has “no one else to turn to.”

With Ariel’s covetousness properly sated, Ursula moves in for the kill. Having lured Ariel with a spell that will turn her human, Ursula demands payment for her services. She wants Ariel’s voice as collateral, which is a bold and deliciously evil move. Ariel’s voice is gorgeous, the seat of her greatest talent and joy. Ariel being a minor with no resources outside her father’s wealth, she has nothing else physical to give as payment. Most disturbingly, this payment sets Ariel up to fail before she’s begun her quest. If she’s voiceless, she can’t communicate who she is, what happened to her, or how she feels toward Eric.

Ursula’s taking of Ariel’s voice is symbolic and connected to Ariel’s deadly sin, too. It might seem odd for Ursula to care whether Ariel is covetous toward Eric and his world or not. After all, Ursula is guilty of at least a few deadly sins herself–wrath, greed, and judging from her first scene, not a little envy of Triton and his court. But nobody knows deadly sin, or how to use it against a protagonist, better than a villain. Ursula proves it when she not only takes Ariel’s voice, but gets her to sign a contract stating said voice is Ursula’s for the duration of their deal. Should Ariel fail, she will never get her voice back. The voice will remain Ursula’s to do with as she likes, while Ariel will belong to her, body and soul.

If Ariel remains voiceless, Ursula knows she can never become anything other than the envious, childish girl she is now. She will never be a part of anyone’s world again. The resentful pain Ariel started with will become the place she lives and can never escape. The difference is, the pain and resentment will be geared toward real love, real freedom, what she could have had. Ariel will be alive, but incapable of feeling what others can feel. She will experience purgatory if not outright hell.

Content and Doubly Crowned

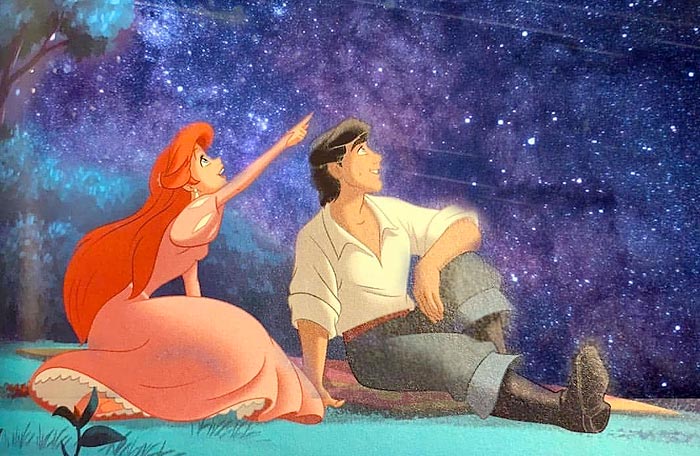

Once Ariel gets to the human world and establishes rapport with Eric, she forgets her envy. She throws herself into enjoying what she has, from luxuriating in a human bubble bath to wringing every drop of experience from a tour of Eric’s kingdom. Viewers indulge in joyous giggles with Ariel as she drags Eric from attraction to attraction, soaking up her first puppet show, bouquet of flowers, baguette, and dance in the town square.

When Eric takes her on a boat ride and they begin to delve into the deeper parts of each other’s personalities, viewers hope Ariel and Eric can find true love and outwit Ursula. After all, they clearly have chemistry. And despite Ariel’s covetousness and Eric’s apparent focus on outward appearances, both are kind, potentially selfless people whose flaws could be overcome. But it is not until Ariel has to face her flaws that she can grow into a mermaid, and a person, who’s ready to claim true love and the title “princess.”

Ariel grows quite a bit during her time with Eric. She uses her rebelliousness and courage to stall Eric’s wedding to “Vanessa,” a disguised Ursula who uses Ariel’s voice to gain Eric’s affections. Ariel’s major part in this involves grabbing and breaking Vanessa’s seashell locket, releasing her voice and recapturing it in time to tell Eric the truth. Unfortunately, Ariel doesn’t get the words out before Ursula’s third day sunset deadline. She turns back into a mermaid in front of Eric. Ursula seizes her, ready to enforce the contract, only for Triton to swim up and command, “Ursula, stop!” He tries to destroy the contract, with Ariel pleading that she didn’t mean to sign it and didn’t know what she was getting into.

Ariel’s remorse and repentance is probably sincere. But many viewers argue that said repentance is two seconds long, and only happens after Ariel is “caught” in her misdeed, so it doesn’t count. This argument is justified. Like a young child in trouble, Ariel just wants the pain and consequences to go away. While that’s understandable, it’s not the mature reaction she needs. That comes a moment later, when Triton strikes Ariel’s name from Ursula’s contract, puts his own name in, and becomes one of Ursula’s polyp slaves. He has sacrificed himself for his daughter, who goes into the final battle determined to save her father and kingdom, not herself or the human she just met. The Little Mermaid doesn’t spell this out, but perhaps appreciation for her father’s sacrifice gives Ariel the real daring and chivalry to help Eric win the final battle.

The movie takes longer to show the good consequences of Ariel’s realizations. Ariel is having a pensive moment on her favorite rock at the surface while Triton, restored after the defeat of Ursula, muses over the story’s events. “She really does love [Eric], doesn’t she?” he asks Sebastian, accepting his daughter’s maturity. Because of this, and perhaps because of Ariel’s emotional growth, Triton grants her deepest desire and turns her permanently human. The last scene is Ariel and Eric’s wedding, wherein Ariel expresses sincere love for her father and Eric bows to him out of respect.

Yes, Ariel gets what she wanted, what she envied. But this only happened after she recognized the covetous and selfish nature of the way she handled her desires. In the end, she becomes a double princess of Atlantica and Eric’s kingdom. Better, rather than being the stereotypical spoiled princess she could’ve been, Ariel shows she will become a brave, chivalrous princess who is appreciative of her kingdoms and worthy of her double crown.

Wreck-it Ralph: Everything to Envy, Nothing Left to Lose

Wreck-it Ralph of the eponymous film doesn’t have a powerful or enviable position when his story begins. He has many more reasons for envy than Ariel does, and nets much more viewer sympathy. Ralph is the title denizen of another eponymous world, the Fix-it Felix, Jr. video game of Litwak’s Arcade. The eight-bit video game doesn’t bear Ralph’s name, and though he is a vital part of it, he is the villain, or “bad guy” as the arcade’s denizens call him and other antagonists. In-game, positive attention such as accolades and fresh-baked pies gets lavished on Fix-it Felix, who fixes the Niceland apartment building Ralph always wrecks. Meanwhile, Ralph always ends up thrown off the roof into a mudhole while the Nicelanders cheer and give Felix a gold medal.

Ralph is not a bad guy in personality, though. He acknowledges he has a real temper and sometimes doesn’t know his own strength. This can cause him to wreck things by accident, or lash out and do so. He also acknowledges at over 6 feet and about 900 pounds (in eight-bit terms) he looks intimidating. But overall, Ralph is what TV Tropes calls a Punch-Clock Villain, someone for whom being bad is just a job. Outside his game, he’s a regular, nice guy, and that’s his biggest problem.

Ralph doesn’t want to be a bad guy, yet most of the other arcade denizens treat him as one. Other characters run when they see him, gasping, “Bad guy coming!” Felix and the other Nicelanders get invited to parties. Ralph is socially isolated. The Nicelanders and other characters have real homes; Ralph has a makeshift home of old bricks and other detritus in the dump. Any envy he experiences is not only understandable, but downright expected. If it weren’t there, viewers might wonder if Ralph understood his position’s implications.

Ralph understands, and the pain of that understanding is as raw as it gets. “Sure must be nice, being the good guy,” he muses during a Bad-Anon meeting. Viewers are unable to call Ralph’s envy sinful at all, or even accuse him of having it, based on the fact that it comes from his environment, which could and should be changed.

The eventual deadly sin lies in how Ralph handles his envy of what good guys have. Ralph starts out with understandable motives and good intentions. But more than the others, Ralph acts as a person who has nothing left to lose. While this can be admirable in some circumstances, it doesn’t work for Ralph. Ralph has nothing to lose because he already feels victimized and ignored. When that depth of pain is allowed to blossom and go unchecked, it becomes the impetus for hurting others and affecting change that can’t be undone.

Opening a Can of Worms…Or Cy-Bugs

Like most complicated quests, Wreck-it Ralph’s starts out simple. In a confrontation with snooty Nicelander Gene, Ralph asks if he would be considered a good guy, thus worthy of fitting in, if he got a medal like Felix. “Yes, but that will never happen, because you’re just the bad guy who wrecks the building,” Gene declares. Ralph denies this, slamming his fists into the multi-tiered anniversary cake. Undaunted, he heads off into the larger video game world to find a medal, starting in the lost and found box at Tappers. Ralph doesn’t find a medal, but runs into a soldier from the new game Hero’s Duty, who tells him the prize for completing that game’s quest is a Medal of Heroes.

The Medal of Heroes, Ralph learns, is better than Felix’s medals. It’s super-shiny and says “Hero” on it. It is “so good, it will make Felix’s medals wet their pants!” Ralph waits for the trauma-stricken soldier to fall asleep in Tappers’ washroom, confiscates his uniform, and game-jumps into Hero’s Duty, with the intent to stay there while it is being played.

This marks Ralph’s first actions connected to sinful envy. He covets a physical object he sees as “better” than one that might be more easily attainable. He takes advantage of a vulnerable person and steals from them. He places another game and world in danger by going against the arcade’s rules about game-jumping while human players are present. If a character does this, they risk putting the affected game out of order, rendering its characters homeless.

Thinking of nothing but his medal, Ralph assumes the identity of Markowski, the soldier whose uniform he stole. He barely survives his encounter with millions of green, glowing, ravenous Cy-Bugs, the virus-ridden insects that have invaded Earth and made the first-person shooter “humanity’s last hope.” Viewers might think this would be enough to put Ralph off his quest and maybe his envy, but he pushes through and obtains an ill-gotten medal. Unfortunately, he lets a Cy-Bug onto a shuttle he hijacks while blasting out of the game, too.

Since Cy-Bugs become what they eat, they aren’t easily killed. This might not be a big problem, except they’re not normal video game denizens. As Sergeant Calhoun explains later, “Cy-Bugs…don’t know they’re in a game. All they know is, ‘Eat, kill, multiply.'” Since Cy-Bugs act like real viruses, their agenda involves “killing” every game in the arcade, Ralph’s included. And since everything a Cy-Bug eats makes it bigger and stronger, these insects are virtually unstoppable.

Ralph doesn’t know any of this, nor did he mean to unleash a killer on his home. When he crash-lands in Sugar Rush, he sees the bug sink into a taffy swamp and thinks it died. But the bug sucked up the taffy and settled in to wait before it could strike again. At its core then, Ralph’s envy has gone up a level, taking on proportions that could harm others in ways he didn’t anticipate and can’t stop.

“You Really Are A Bad Guy!”

Unaware of the destruction he’s wrought, yet still focused on himself, Ralph determines to escape Sugar Rush as fast as possible. To him, it’s a brightly-colored, saccharine “candy go-kart game,” so he figures, how hard could escaping be? But he doesn’t count on resident Vanellope Von Schweetz, who steals his medal thinking it’s a gold coin. “Race ya for it,” Vanellope challenges, and Ralph does try. But his size, frustration, and unfamiliarity with Sugar Rush’s mechanics–such as, double-striped candy cane tree branches break–mean Vanellope trounces him. Vanellope tries to engage Ralph, albeit with insults and snark, asking why he can’t just “go back to [his] own dumb game” and win another medal, letting her keep this one since it’s important to her, too. But again, Ralph lets envy and selfishness win. He calls Vanellope a “guttersnipe” and says she “wouldn’t understand” his motives because “it’s grown-up stuff.”

Ralph only agrees to help Vanellope after she explains that if he helps her build a go-kart, she can guarantee she’ll win a race and give him back the medal she’ll use to buy her way in. Ergo, they both win. Vanellope gets to be a real racer, and Ralph gets to return to Fix-it Felix Jr. as a good guy, with proof of his status.

Vanellope makes a compelling argument, Ralph admits, but her point of view is still not valuable to him. They are neither partners nor friends, he’s quick to point out. As before, though, conflict changes Ralph’s outlook. Shortly after meeting Vanellope, he sees a group of Sugar Rush racers taunting her homemade, pedal-powered go-kart and mocking the fact that she’s a “glitch” who randomly blurs in and out of focus. Vanellope tries to defend herself and stand up for her right to “race like you guys,” but the others don’t listen. Taffyta Muttonfudge says Vanellope’s glitch could put them all out of order and she’s “an accident waiting to happen.”

This touches off the other racers imitating Vanellope’s glitching with exaggerated faces and slurred speech. Ralph races to Vanellope’s defense–“Scram, you rotten little cavities!” But while his intimidating presence does scare off Vanellope’s bullies, it also alerts King Candy and the royal guard to Ralph’s unsanctioned presence, and the fact that Vanellope is outside her permitted purview. The heroes are forced to work as a team to escape capture. Ralph gets a double upshot of growth when he shows compassion and chivalry, putting aside his agenda for Vanellope’s sake.

Ralph continues conquering envy as he works with Vanellope. After seeing she has to live in an unfinished bonus level “like a little homeless lady,” and hearing she’s been outright told she’s not supposed to exist, Ralph realizes how much the two have in common. He immediately “wrecks” Vanellope’s Diet Cola Mountain home into the shape of a track and teaches her to drive the kart they made together before being detected. Ralph isn’t exactly a wise or caring mentor, and Vanellope’s driving efforts are more than a little reckless. Thanks to falling Mentos reacting with the cola, she “almost [blows] up the whole mountain” more than once. But she and Ralph eventually bond over their mentor-mentee relationship style. Vanellope, who has lived in total isolation, gives Ralph her trust. Ralph, who has built his identity on getting what others have, places her happiness above his. When she says, “I’m already a real racer; it’s in my code,” Ralph believes her, which lets Vanellope believe more in herself.

Ralph is not out of the green-eyed monster’s clutches yet, as viewers learn during the climax. Just before the big race she’s entered using his medal, Vanellope rushes off to get Ralph something she forgot. Meanwhile, King Candy shows up looking for a private word with Ralph. He explains Vanellope can’t race, ever. If she does, he says, players will begin choosing her as their avatar. “And when they see her glitching and twitching and just being herself…we’ll be out of order,” he says. Since glitches can never leave their games, Vanellope won’t be homeless when Sugar Rush’s plug is pulled. She’ll die, with no hope of regeneration anywhere.

Ralph can’t let that happen, which seems like a selfless decision. But in urging Ralph to tell Vanellope the truth and prevent her from racing, King Candy brings Ralph’s desires and bad guy status into the conversation. Therefore, Ralph concludes if he doesn’t hurt Vanellope, he’ll lose his one chance at being a good guy. Viewers infer Ralph might rationalize, sometimes good guys have to make bad choices.

A bad choice is exactly what Ralph makes. He ignores the sugar cookie medal Vanellope tries to give him, implying it’s not “real” or as good as the one he sought. He tries to tell her the truth, but gives in to frustration when Vanellope protests King Candy is the bad guy, Ralph “sold [her] out.” The frustration and Ralph’s fear of Vanellope’s death create an emotional storm. Ralph lifts Vanellope to the branch of a candy cane tree and suspends her by the back of her hoodie, where she’s forced to watch while her friend destroys her kart.

“You really are a bad guy,” Vanellope sobs. His “bad” identity cemented and now inescapable, Ralph abandons Vanellope and heads back to his game, disgraced. He’s set up to let pain, envy, and the knowledge of what he’ll never have eat him alive like a cyber virus.

“There’s No One I’d Rather Be Than Me”

Ralph, Vanellope, and unknowingly the rest of Litwak’s Arcade have reached their darkest moment. Felix and Calhoun have been tracking the Cy-Bugs Ralph unleashed, but with no success, so the bugs are poised to kill the arcade. Felix, who went looking for Ralph, is locked in King Candy’s “Fun-geon.” The Sugar Rush race may continue, but even if Cy-Bugs don’t get to it first, Vanellope’s lost her chance to compete. Meanwhile, Fix-it Felix Jr. has been mistaken for out of order, so Ralph has nothing to do but wait for homelessness. As lone Nicelander Gene puts it, Ralph got the medal he coveted, but now all he gets is to live alone in the penthouse instead of the garbage. Ralph’s story might’ve crash-landed there, except he looks across the arcade at Sugar Rush and spots Vanellope’s picture on the side of the game console. Why would a character who’s not supposed to exist be prominent enough for a picture?

Ralph game-jumps again, and this time, dedicates himself to righting wrongs for others first. He wrecks the Fun-geon and admits his envy-driven mistakes to Felix, who has learned what it feels like to be Ralph, “rejected and treated like a criminal.” Felix promises to find Calhoun and back Ralph up on his mission to save Vanellope and the arcade, while Ralph goes in search of the truth about his friend. His interrogation–and halitosis–crack King Candy’s henchman Sour Bill, who admits Candy lied. If Vanellope crosses the finish line in a race, “the game will reset and she won’t be a glitch anymore.” Worse for Candy, the reset will mean Sugar Rush’s citizens will remember he locked up their memories and usurped a throne that was never his. Vanellope’s the rightful ruler, Bill explains, but Candy made her a glitch so he could take over her game and become its most powerful racer. He’s now locked Vanellope in a different Fun-geon area so the race can proceed as he wants.

Ralph tracks Vanellope down, and after hearing him admit he’s “an idiot,” “a selfish diaper baby,” and “a stinkbrain,” she forgives him with a big hug. Ralph presumably explains everything on the way to the race, encouraging, “Just cross the finish line and you’ll be a real racer.” Fully confident she’s already there, Vanellope takes off. Not long into the race however, the Cy-Bugs invade. Felix and Calhoun focus on getting Sugar Rush’s civilians out of the game, while Ralph determines to defeat Candy, who’s using the bugs to his advantage.

By the time Ralph reaches Candy, he’s become a humanized Cy-Bug and set his sights on Vanellope. “Let’s watch her die together, shall we?” he taunts Ralph, becoming larger and stronger by the second. As villain and hero duke it out, Candy morphs one last time.

“Turbo?” Ralph gasps at finding himself face to face with the whole arcade’s legendary nemesis. Turbo, an old eight-bit character presumed dead, was the first game-jumper. Once the star of his eponymous game, he became enraged when a new game called Road Blasters got plugged in and “stole [his] thunder.” Turbo meant to take over every game, becoming the center of attention everywhere. Yet he ended up “putting both games, and himself, out of order,” until the events of Wreck-It Ralph. Now, with another takeover threatening to crumble, King Candy seeks to kill Vanellope and Ralph, and become “the most powerful virus in the arcade,” something whose prestige no one can steal.

Up to the last second, it looks like Turbo will win. But Ralph and Vanellope pull off their finest bit of teamwork yet, using their knowledge of falling Mentos and diet Cola to create a beacon that will attract and kill the Cy-Bugs, of which Turbo is now one. The ensuing fall will likely kill Ralph, but Vanellope, tucked safely in her kart, will make the finish line and reclaim her throne. Ralph at peace with his sacrifice, no longer concerned with what he has or can get from others. “There’s no one I’d rather be than me,” he declares as he falls, and viewers know he means it.

Ralph’s surprise crash landing into a pool of chocolate, so like the mud of home, becomes doubly satisfying. So too, does Ralph’s new life at Litwak’s. He remains his game’s bad guy, and keeps getting thrown in the mud every day. Now though, he gets the friendships and respect he wanted, and appreciates them more, having faced a villain who let envy take over as Ralph almost did. Ralph also gets the friendships and love of others in the arcade, especially Vanellope. “If that little kid likes me, how bad could I be?” he asks. Viewers know now, Ralph is good in every way that matters.

Wrath: Jack Kelly and Elsa

Next up is wrath, sometimes rendered as “anger” but more commonly known by its shorter and more Biblical name. Wrath feeds into, or can result from, pride, envy, or both. That is, if someone goes too long with an inflated, bruised ego or experiencing the resentment of envy, he or she will become angry. That anger can consume, to the point of being that person’s dominant emotion or motive.

Christianity.com defines this deadly sin as “strong vengeful hatred or resentment.” Philosopher Thomas Aquinas made wrath synonymous with anger and called it “a passion,” which “is evil if it set the order of reason aside.”

Be careful too, not to confuse the wrath of humans, real and fictional, with the wrath of God. God’s wrath is different from humans’ because of God’s holy nature. Beyond that, the Bible and presumably other Holy Books do make allowances for anger toward deeds deities hate. The Bible clearly lists the seven deadly sins as the ones God hates.

Righteous anger also occurs when anger “attacks the sin instead of the sinner,” reacting to another person being abused or mistreated (crosswalk.com). An example might be someone physically subduing a human trafficker, or verbally attacking a person who abuses an elderly or disabled individual. This is the kind of wrath God experiences, and the kind of wrath He does allow His people to indulge, but if and only if it is under His conditions and tempered with reason and self-control.

Under these definitions, most Disney characters who experience wrath are villains. However, a few protagonists do as well. Jack Kelly of the Disney musical Newsies and Queen Elsa of the Frozen duology are two of the most interesting cases. Their wrath is partially, if not fully, built on righteous anger. Both get into trouble when they let their anger turn inward. Once that happens, they, the people, and the environments around them begin to crumble. The people that in their passion, they were so desperate to help, Jack and Elsa end up hurting. Unlike the other characters, Elsa and Jack deal more with internal conflict and have to decide how much of their passion they’re going to keep.

This time, we’ll look at our male protagonist first. This is not because males are more prone to wrath. Rather, we’ll look at Jack Kelly first because his wrath takes a more “traditional,” anger-based form, while Elsa’s comes from different emotions and motives.

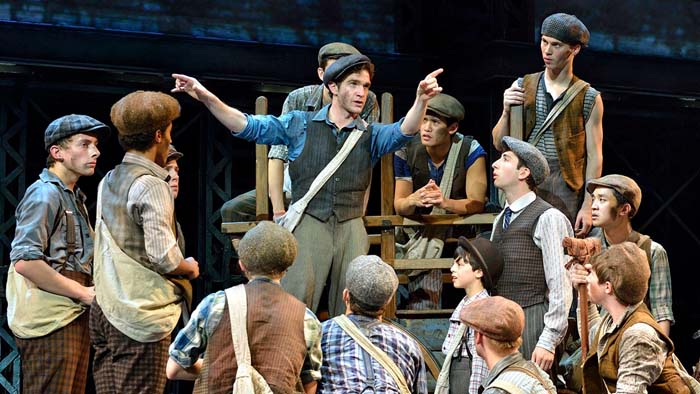

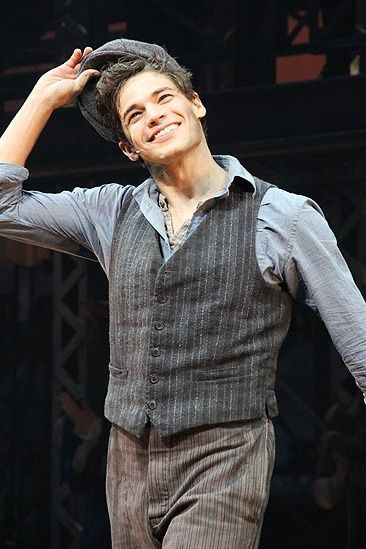

Jack Kelly: Mad as Hell and Not Gonna Take It Anymore!

Viewers can meet Jack Kelly in either the 1992 film version of Newsies directed by Kenny Ortega or the 2012 Disney musical directed by Jeff Calhoun. Either way, Jack doesn’t seem wrathful at first. He’s a romanticized version of an 1899 New York City newsboy. As Stephen of the InReelLife channel says in his video “How Everyone Reacts to Newsies,” “Nobody living below the poverty line in New York is this happy.”

And yet, Jack Kelly has transcended the hardscrabble life of a newsie. He gets up early to sit on the lodging house rooftop, dream of escaping out West to Santa Fe, and share that dream with his best friend Crutchie, fellow newsie, polio survivor, and honorary brother. He rhapsodizes about the big life he’s going to live out there, “plantin’ crops, splittin’ rails,” and “swimmin’ the Rio Grande” when he’s not “just [lyin’] around all day” (Newsies track 1).

Jack is also quick to make a joke when things get too serious. When Crutchie worries his disability makes him a burden, Jack laughs it off. “That bum leg of yours is a gold mine,” he says. Crutchie may have the famous “smile that spreads like buttah,” but viewers quickly peg Jack as the most genial and encouraging newsie of the Manhattan bunch (Newsies track 2).

On closer review though, it’s clear some of Jack’s cheerfulness is a mask for deep-seated frustration. He longs for a place “where it’s clean and green and pretty,” but not for its own sake (Newsies track 1). He doesn’t hate New York City because his job is hard, the pay is lousy, and the streets are mean. Jack tells Crutchie the rich “bosses” of the city, “broke [his] old man.” Since we never hear anything about Jack’s mother, that means he was orphaned, presumably very young. “Broke” connotes Jack’s father suffered, and that Jack had to watch. “Well, they ain’t doin’ it to me!” Jack yells over the fire escape. Nobody answers, but they don’t need to. Jack’s not angry with anyone in particular. He’s fed up with his city, his circumstances, and his inability to control his own life, and someone’s going to hear about it.

Viewers catch other glimpses of Jack’s angry bent as the story progresses. He tells Crutchie to “quit gripin'” about his disabled leg, and dismisses the idea that the disability could get the other boy “locked up in the Refuge for good.” In so doing, Jack dismisses that he has been in the Refuge too and knows the institution is squalid, abusive, and no place for an able-bodied kid, let alone a disabled survivor of a serious disease. He acts as a big brother to the other newsies, but bosses them around or ignores their concerns. Jack calls his newspaper distributor “Weasel” instead of Mr. Wiesel and doesn’t hesitate to get mouthy when the former cheats the newsies out of papers. He displays a hair-trigger temper, especially around Oscar and Morris Delancey, who work at the distribution center and push other newsies around.

In the latter two cases, Jack is justified according to the “righteous anger” definition. However, the fact that he goes straight from verbal confrontation to all-out fisticuffs with the Delanceys–including using Crutchie’s mobility aid as a weapon without permission–is not in Jack’s favor. Additionally, his tendency to lean into frustration even with his friends, or assume their legitimate worries are whining and griping, makes him less sympathetic.

Striking and Seething

Being an angry teen does not make Jack guilty of wrath. If it did, every newsie in New York City would carry that guilt. Wrath kicks in for Jack when his situation goes from difficult to untenable. Jack and his fellow newsies sell the New York World to feed themselves and in the case of “new kids” Davey and Les Jacobs, their families. So when publisher Joseph Pulitzer raises his prices by ten cents, and convinces fellow newspaper publishers to do the same, the newsies are in an impossible position. They can’t afford the new price. As it was, most of them made about 30 cents per day in 1899 money, and more than half of that went to meals and lodging house rent.

They’ll still have to pay back full price for every paper they can’t sell at the end of each day. Newsies who don’t already sleep on the street will probably have to, and although some joke about doing it “in a worse neighborhood,” that implies vulnerability to all kinds of danger. Plus, the newsies would be considered delinquent or vagrant, so places like the Refuge would become a real possibility for all of them. Since the Refuge functions as both a juvenile jail and a prison pipeline, a newsie could find himself locked up for years if not the rest of his life.

Jack Kelly taps into his existing anger, scales a statue of Horace Greeley in Newsies’ Square, and exclaims, “Pulitzer and Hearst, they think we’re nothin’…they think they got us…do they got us?” When he gets a vehement “no,” he yells, “[They] have to respect the rights of the workin’ boys of New York!” Jack demands, “Are we just gonna take what they give us, or are we gonna strike?” The newsies agree to strike, committing to block their ears when the circulation bell rings and show no intimidation if scabs like the Delancey brothers menace them.

This is not wrathful. A strike is the most logical place for the newsies to put their anger, especially since they’re minors with little to no other recourse. The resulting musical number, “The World Will Know,” is a memorable rallying cry for the newsies and any viewer who has participated in or supported peaceful protesting. Note, however, some of the lyrics in that number, especially from Jack. “We’ll do what we gotta do until we break the will of mighty Bill and Joe,” he sings (Newsies track 7). It won’t have the same affect on a wealthy publisher as it did on Jack’s dad, but one wonders if he remembers what “breaking” someone’s will looks like.

Similar lyrics such as “we’ll kick their rear,” “we’ll stomp all over you,” and “[we’ll] give them a war” speak to a level of anger the newsies may have experienced, but not admitted before. They’re not being literal, and they, Jack especially, are justified in their words and actions. The strike itself is not a sin. But the heat behind these words is a precursor to the vitriol behind wrath, and Jack must be careful because he’s the leader. He has the power to turn the strike in any direction, but is so emotion-fueled, he can’t see the practical side of what that means. Once he does, it may be too late for him, the other newsies, and the working kids of New York he’s fighting to protect.

Burning Bridges and Brothers Alike

The strike starts out fairly calm. Davey Jacobs cautions Jack the newsies can’t “soak” (beat up) scabs or other adversaries because they’ll lose credibility. Despite his temper, Jack sticks to that. Initially, he’s willing to let the Manhattan newsies go it alone. He believes they have the strength to see the strike through no matter how long it takes. The support of two intrepid journalists, Bryan Denton in the film and Katherine Plumber in the musical, replace some of Jack’s anger with optimism.

The musical adds the possibility of love, as Jack and Katherine explore an enemies-to-lovers attraction. Yet with each passing day, the reality of Jack’s situation digs deeper. He’s not just the leader and “big brother” to the Manhattan newsies. Now he’s a strike leader, and if that strike doesn’t succeed, he’ll let his brothers down unforgivably. The strike was essentially his idea, so he will carry 100% of the blame whether or not someone else volunteers to take it.

The pressure leads Jack to snark and lash out at Katherine in the musical, citing her femininity and privilege as reasons she’ll never understand him. In the film, he gets into a confrontation with Brooklyn newsie “king” Spot Conlon, rejecting Spot’s point of view when the latter questions Jack’s commitment to the strike, and nearly coming to fisticuffs when Spot refuses to involve Brooklyn’s newsies because Jack hasn’t proven he’s serious or “in it to stay.”

Jack’s anger doesn’t turn to wrath however, until the end of Act I. Here, the newsies hold a rally at the distribution center, during which Davey begins the show-stopping “Seize the Day.” The song touches off a fun number wherein the newsies release pent-up emotions, destroying newspapers, bantering, insulting Pulitzer and other publishers, and cavorting all over the place. But over time, the scene’s chaos increases. Property damage is implied; it’s minor, but a punishable offense. The Delancey brothers show up, and several newsies get physical with them, as well as other scabs.

The chaos reaches a fever pitch, and Wiesel calls the police, who presumably bring the Refuge’s Warden Snyder with them to keep order and pose a threat. In the ensuing attack, several newsies sustain implied injuries, some fairly serious. Crutchie attempts to hide, but is discovered. Snyder beats him with his own crutch, and Crutchie is dragged off to the Refuge, screaming Jack’s name. Considering his disability and latent illness, it’s strongly implied he’ll be the strike’s first casualty.

Jack flees to the lodging house rooftop, consumed with his own trauma, guilt over Crutchie’s fate, and self-hatred. The simmering, potentially dangerous anger we’ve seen is now the deadly sin wrath. Interestingly, it’s turned inward. “We finally got a headline, newsies crushed as bulls attack! Guys are fightin’, bleedin’, dyin’, thanks to good old Captain Jack!” he sings in the “Santa Fe” reprise.

Jack’s not threatening anyone. He’s not getting physical or destroying property. But his wrath is more dangerous here than before. It inspires him to run, to not only forget his brothers, but betray them, including his closest one. “Crutchie’s callin’ for me, dumb crip’s just too damn slow!” is included in the musical. Many viewers rightly excoriate Jack for using the slur, true to the time period or not. Even had he not used “crip” (and some musical directors leave it out), Jack’s still on the hook for blaming Crutchie, the victim, for getting assaulted and essentially kidnapped. (Unlike the other newsies, Crutchie did not commit vandalism, so while he could be taken to the Refuge based on orphan or disabled status, his arrest would be unwarranted).

Further, Jack is guilty in the eyes of viewers, fellow newsies, and himself for choosing to run and hide, possibly skip town, rather than finish what he began. As Act I closes, he becomes the epitome of a protagonist who “sets reason aside.” Some of his wrath was once righteous, but the selfish portion focused on “they ain’t [breakin’] me,” “I’m dyin’ to get away,” has eclipsed it. When Davey confronts him with the truth–he’s a quitter and a coward, he could still win if he gave himself a chance–Jack is too mired in hatred to care. When Pulitzer offers him a deal with the devil–scab in exchange for freedom and a railway ticket, or see himself and his friends permanently thrown in the Refuge–Jack is prepared to give in. In the musical he doesn’t, but the film has him break, showing up in a suit with pockets full of blood money to convince the other newsies to give up the strike. Jack’s wrath spills over onto them as they label their brother a traitor.

Writing a New, Triumphant Headline

As much as Jack tries to harden his heart, he is still a hero deep down. The musical shows this as he takes time to talk out his emotions with Katherine. Rebuilding that relationship isn’t easy. Pulitzer exposed her as his daughter, and Jack justly felt double-crossed. But Katherine clarifies she doesn’t agree with her father’s ethics, or lack thereof. When she finds out the truth about the Refuge from Jack and his sketches, she’s horrified and ready to help him win the strike “once and for all.”

As for the other newsies, viewers don’t see them returning to Jack’s side in real time. But once Katherine engineers a plan to use Pulitzer’s old printing press for strike purposes, everyone’s on board, and reconciliation is implied during the “Once and for All” musical number. The time it takes to put plans into action gives Jack the opportunity to reflect and redirect the passion that was never wrong in itself, but needed a better outlet.

Both incarnations of Newsies show Jack turning against Pulitzer and “taking a third option.” He uses his talent as an artist and his journalist allies’ writing to create the Newsies’ Banner and associated headline THE CHILDREN’S CRUSADE. This headline details the plight of child laborers across New York City and exposes the Refuge as a bastion of abuse and exploitation. Every laborer under 21 in New York City, from newsies to factory workers to shoeshine kids, goes on strike, proving to adults like Pulitzer that, “They think they’re runnin’ this town, but this town’ll shut down without us” (Newsies track 16). As a direct result, Governor Theodore Roosevelt shows up to talk Pulitzer into giving the newsies a fair deal and get Crutchie out of the Refuge.

Roosevelt provides the power Jack needs for credibility, but the governor’s encouragement, plus the renewed confidence of his allies, leads him to take the lead in negotiating with Pulitzer. And while Jack didn’t have the power to close the Refuge and arrest Snyder himself, it’s implied his new job as a newspaper cartoonist will keep these injustices at the forefront of New Yorkers’ minds. Thus, villains like Snyder aren’t as likely to get away with as much as they have before.

By the end of Newsies, Jack has learned a necessary and complex lesson about wrath. Wrath is still a deadly sin, and it’s dangerous to let anger get that far. Jack also has to learn the temptation to run and bury emotions further will only result in more “burns,” for the self and others. But anger is not a sin and can be righteous. The passion that leads to anger has its place. Once Jack learns where to put that passion, he’s in a much better position to be a true brother in his newsie family and focus on mental and emotional growth. It’s implied he’ll become a passionate adult who doesn’t tolerate injustice, but tempers that intolerance with patience, a combination sure to make positive headlines.

Elsa: Freezing Outside, Burning Inside

So far, sinful Disney protagonists have presented as people with justifiable reasons for their behavior. Elsa fits this mold, but distinguishes herself. She, too, looks like one of the last protagonists a viewer would associate with a deadly sin, because she’s so focused on “[being] the good girl you always have to be.” Yet Elsa sticks out because she’s the last person one might expect to be guilty of wrath, in particular. Her levelheaded, cold personality, keen intelligence, and associations with ice, make her appear the least wrathful character in Frozen. She’s not revenge-driven like Hans, and she’s not as passionate as Anna. As with Jack Kelly, viewers have to look beneath Elsa’s surface to find her wrath. Once they do, it might be more obvious and harder to master than Jack’s.

Viewers meet Elsa and Anna when they’re little, with most sources placing them at 8 and 5, respectively. Elsa is the more serious sister, preferring to sleep when it’s too early to get up, coming down the stairs more slowly than Anna, and keeping her hair and clothes neater. But in general, she’s a cheerful, carefree kid. When Anna begs her, “Do the magic,” Elsa has no qualms about creating a winter wonderland for the two sisters to play in. This includes a snowman, who Elsa christens Olaf. Danger and darkness have never crossed Elsa’s mind, let alone deadly sins. That is, until one of her ice shards ricochets and strikes Anna in the forehead, knocking her unconscious.

Elsa’s parents, King Agnar and Queen Iduna, take Anna to the local trolls, where Grand Pabbie revives her. Elsa is thrilled and relieved to have her sister back. But Anna’s restoration isn’t so simple. Grand Pabbie warns Elsa that while her ice powers have beauty, they are dangerous. Therefore, Grand Pabbie and Elsa’s parents agree Anna can never know Elsa has the powers. Her memory of her close relationship with Elsa is erased. Although Grand Pabbie promises to “leave the fun,” this taints Anna and Elsa’s sisterhood for the next decade or so. Agnar and Iduna isolate Elsa from Anna and Arendelle, encouraging her to wear gloves to help control her powers. “Conceal, don’t feel” becomes Elsa’s motto, to the point her powers are neither used nor acknowledged, nor does she get any positive attention.

Meanwhile, Anna tries drawing her sister out. But the more she encourages Elsa to spend time with her, the more Elsa isolates herself. The older Elsa gets, the more painful her isolation becomes. By the time Elsa is 11 or 12, touching a windowsill with her bare hands terrifies her because she leaves behind a sheet of ice. She can’t accept affection, pleading with her parents, “Don’t touch me! I don’t want to hurt you!”

Elsa probably feels some frustration at her isolation, and at her inability to tell Anna the truth, as well as her compulsion to push Anna away when as the latter sings, “We used to be best buddies.” As she grows up, Elsa becomes not angry, but anxious. She’s so fearful that when Agnar and Iduna leave for a long voyage, they have to assure her, “You’ll be fine,” despite the fact Elsa is heir to the throne and 18. When the princesses’ parents die on the voyage, Elsa retreats further into her anxiety.

Viewers see Elsa insisting on physical isolation through closed gates and emotional isolation through gloves, closed doors, and an overly introverted nature, as she prepares for her coronation. She’s determined to be “the good girl” queen she’s been prepared to be, to “put on a show” if necessary, to win her subjects’ approval. If Elsa does otherwise–if she [“makes] one wrong move,” she’ll expose her ice powers. She’ll cast aspersions on her ruling ability at best. At worst, she’ll be the danger, if not monster, Grand Pabbie and her parents implied she might become.

Fearing, Yet Becoming, the Monster

Elsa stays in this fearful state throughout most of Frozen. This might cause viewers to think she’s not guilty of wrath, because fearful people don’t usually lose their tempers, seek revenge, or vent their passions. But as many people and characters from Dr. Phil to Yoda have said, anger is the child of fear. Yoda specifically once said “anger is the path to the dark side.” Elsa’s steps toward her dark side are subtle. Yet they do exist and have eventual wrath as roots.

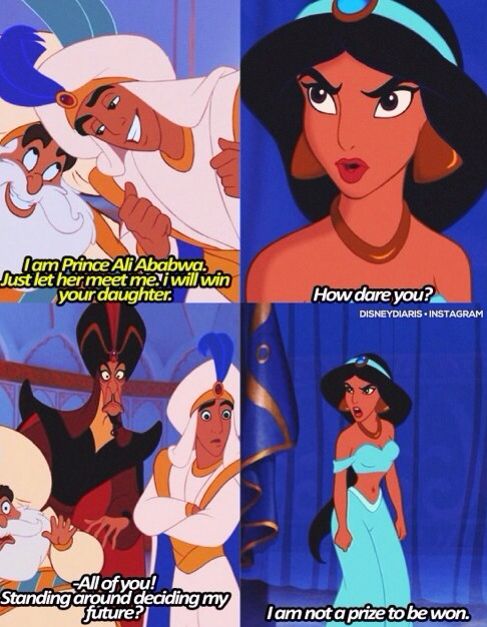

Elsa’s first and most obvious connection to wrath comes through her powers. When Anna announces her engagement to Prince Hans at the coronation ball, Elsa says, “You can’t marry a man you just met” with trademark levelheadedness. Most viewers agree she’s right. But she’s so matter-of-fact and cold in her delivery, it pushes Anna over the edge. The two argue, and Anna throws her sister’s pain in her face. “What do you know about love?” she demands. “All you know is how to shut people out!” Elsa maintains dignity and tries to leave, but Anna won’t drop the issue, so Elsa ends up yelling, “Enough!” Pointed ice shards shoot from her hands and overtake the ballroom. The entire court and guests are horrified, and the Duke of Weaselton proclaims the new queen a monster.

Furious and terrified, Elsa flees the kingdom, covering the landscape in eternal winter. As Anna notes in a cut song, the fjord in and out of Arendelle is frozen over, so everyone is trapped. The abrupt season change has decimated supplies and travel possibilities, so Elsa’s passion may have harmed her kingdom permanently.