Dystopia: Hope in the Face of a Seemingly Impenetrable System

No freedom, no privacy, self-expression and self-identity suppressed: these are the marks of the nightmarish societies of dystopian literature. But this isn’t all there is. Every story hinges on hope, on an individual wanting something better. Even in a society that is completely repressed by the state, there is always someone who wants more than the system will allow. The prism through which we see the book’s events is the individual’s journey. They all try to bring about change in their own lives and most attempt to be part of reforming the system. But as much as the individual shows there can be hope, the system is all-powerful. For change to be a possibility there needs to be a dynamic force acting alongside the individual.

What Brings Them Hope?

A dystopia is a tyrannical society where everyone is expected to act a certain way or suffer the consequence. Every state presents an ideology, a claim that the way things work is in the best interests of everyone. So how does anyone have hope? What makes them set themselves apart from the rest of society by wanting more?

Hope Ignited in 1984

1984 1 depicts a society that is utterly repressed by the Party, the State Government, and its figurehead, Big Brother. Surveillance is everywhere: telescreens function both as TVs and surveillance cameras, neighbours spy on each other and every poster declares that Big Brother is watching you. Citizens have no choice but to follow the party line or be punished. The Party justifies its every action with the threat of war, claiming that Big Brother is a saviour, protecting its citizens. Most are too frightened to do anything but accept these claims.

But Orwell’s hero is different. Winston has always wanted more than life in a state where the government constantly watch their citizens. When he starts writing a diary he is able to express every pent-up thought and emotion. This ignites his hope for change. Almost instinctively, Winston repeatedly scrawls ‘down with Big Brother’. He recognises that freedom is simply the ability to speak the truth without fear of government reprisal. This diary is just the starting point. Once he meets Julia and falls in love his hope accelerates. In her, he finds someone who hates the Party as much as he does and wants to defy it.

As much as he wants change, though, he wonders if it will ever happen. This is a government that doesn’t just use constant surveillance. It also has a policy of ‘doublethink’ where citizens, even if they know the truth, must accept whatever version of events the Party broadcasts. Winston’s small hope for revolution is the proletariat, who are less closely monitored. This is a slender possibility. The proles are only less tightly controlled because they are constantly occupied by manual labour. Winston’s hope for the first half of the novel is a despairing hope. As much as this desire for change is heightened, he is unsure if it will ever be fulfilled.

Hope Emerges in We

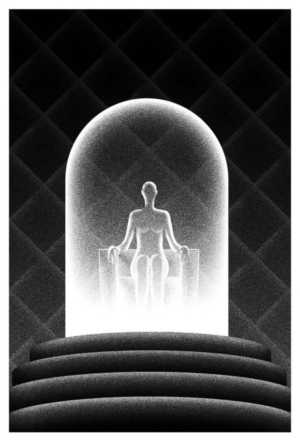

1984 shows a pre-existing hope become stronger, even if the possibility of change is small. In We 2 and Fahrenheit 451 3 however, hope emerges because another person makes the protagonist aware of the true state of the world around them. We portrays the society of OneState where everyone lives as part of a collective under the leader, the Benefactor. In this distant future the government claims that everyone is not an individual but part of something greater. They stress that as a collective society has efficiency, technological prowess and peace. Individual identity doesn’t exist. Instead of names, everyone is assigned a letter and a number. Everything is mechanised: everyone eats, sleeps and works at the same time as each other. They live in glass towers and are constantly watched by spies known as ‘guardians.’

We inspired 1984 but unlike Winston, Zamyatin’s protagonist, D-503, never questions the system until he meets the radical I-330. When she asks how he can be so sure they’re the same if they look so different, he becomes confused though he quickly rejects her point. As they grow closer, he tries to resist her charms but she makes him hope for something more than being part of a collective. He starts to think, to want to be an individual in order to be with her. At first, he sees love as an illness that he needs to recover from, something that goes against the rational world he believes in. But he comes to realize that this sickness, the pain of loving her, is something that’s allowed him to grow: ‘I’m sick, I have a soul…but isn’t blooming a sickness?’ Despite this realization, he is torn between wanting her and still seeing beauty in the strict order of OneState.

Hope Emerges in Fahrenheit 451

Just like We, in Fahrenheit 451 it is through another person that the protagonist starts to hope. In this reality books are burnt. People are encouraged not to think. Instead they watch wall-to-wall 4D TV, drive fast cars, take drugs and engage in mindless violence. Political correctness is taken to an extreme as books are first censored and then banned. The Government wants everyone to be made equal. But even before censorship, books were neglected. The system of burning books is the final push to make sure no one thinks.

Guy Montag is a fireman, which in this society means he burns books and is very much part of the system. Everything changes after he meets Clarisse, his new young neighbour, who makes him realise that he wants more in life than the mindless pleasure of drugs and technology. Clarisse really looks at the world and inspires Montag to do the same: to watch people, look at nature and question the way technology has become so dominant. When she asks him if he is happy, he thinks of the books he’s harboured over the years. Unlike D-503, there was always some subconscious part of him that found something lacking in this world. However, it is through her that he admits to himself that he wants more and starts hoping for something better. Their conversations coupled with the final push of seeing a woman dying as her books are burnt around her makes him unable to contemplate being a fireman again. Instead, he hopes that by reading books he will have the chance to find something more meaningful.

Hope Inspired by the System in Never Let Me Go

Never Let me Go 4 is different in that the individual’s desire for more actually comes from a belief that the system might grant them special favours. Ishiguro creates a world where the desire to find a cure for illness has gone too far. Human clones are created to be organ donors. They are not considered human and simply expected to go through four donations and then die. The novel follows Kathy, Tommy and Ruth, who are brought up in the seemingly idyllic world of Halisham, a rich English boarding school. Here, they’re given the best education and encouraged to be creative. At the same time they’re taught that they will first be carers, to those that donate, and then donors themselves. When Kathy and Tommy fall for each other, they hope that Halisham’s privileges will mean they get special favours, that Tommy will be able to get a deferral from donation if they prove their love. They’re even more desperate because he is on the third of four donations.

So, it’s clear that the system by stressing that this is a voluntary decision is twisting the truth. What’s more by calling the clones donors, they suggest that the clones’ identity is only in terms of what they can do for humans. Unlike most dystopia, this is a society that claims its policies benefit not everyone but everyone that matters. Kathy and Tommy’s hope, therefore, is only in the system giving them something temporary. Tocker and Chartoff, two literary critics, stress that

‘the most they seek is deferral—not escape—from what they still call “donations”…that the novel…explores…the educational techniques that have conditioned them to accept their predicament.’ 5

Their education does ensure they never hope for complete freedom. But these critics don’t recognise that in looking for something temporary they’re going against what the system typically allows. Nonetheless their hope is still limited and derives from the system.

Hope Inspires Action

The individual doesn’t just hope for more, they act on this hope, even though the system is all-powerful. The dystopian story needs the individual to show there is someone who wants more than the narrow parameters the system allows and will act against the system. But what is it that they want for themselves? They are all seeking some type of individual freedom and this is typically motivated by love. Love is overwhelming and enables them to act, to overcome their fear of what the state might do to them. More often than not, hope does not simply inspire them to improve their own lives but to be part of changing the system.

Defying the System in 1984

In 1984 Winston hopes to be able to say or do what he wants in a society where the state holds all the control. His affair with Julia starts off as a means to defy the state’s emphasis on chastity or marriage just to produce children. However, they fall in love and as much as they fear capture, they take action. Winston rents shopkeeper Charrington’s upstairs room because he wants a private space together which the state cannot access. By loving her rather than simply acting on lust, he more profoundly rejects the system. This is a state that demands absolute worship but Winston’s greatest loyalty is now to the person he loves.

Winston has new hope because of love but he’s always hoped for change in the system. He suspects that O’Brien, an inner party member he is acquainted with, is a secret rebel. So when O’Brien asks to meet, Winston is ready to take action. He might have taken this step regardless, but his rebellious actions with Julia mean he is more prepared to act against the system. Through O’Brien he and Julia become part of the Brotherhood, a rebellious force working against Big Brother. But O’Brien warns them that any actions they take are simply preparing the groundwork for the future.

‘There is no possibility that any perceptible change will happen in our own lifetime. We are the dead. Our only true life is in the future.’

Although they can’t change the present Winston and Julia still have hope. The system might be truly entrenched but they are ready to try to be part of changing it for the future.

Love Motivates Rebellion in We

Unlike Winston, who rebels both because of his hatred of the State and love for Julia, D-503 primarily acts against the system because his love for I-330 can’t be fulfilled in the society of OneState. He doesn’t just start thinking like an individual; he starts acting against the system. When they’re about to sleep together for the first time, he thinks of all her possible lovers and contemplates killing anyone that would touch her. Such emotion in a state where anyone can request anyone else for sex shows how much he wants to keep her with him and him alone. But I-330 is not simply a rebel; she is the leader of the Mephi, a rebellious group who live beyond the wall that surrounds the city. D-503 knows that being with her means that he cannot simply desire individuality. He must defy the system and be part of the movement towards change. His main act of rebellion is to sabotage the INTEGRAL. This is a rocket ship carrying propaganda by OneState to alien civilisations. His aim is to give the rebels a weapon to blow up the wall separating the citizens from nature. But, despite his best efforts, his actions don’t work out.

There are moments though when he is so intoxicated by the hope for more that he urges others to rebel. When I-330 takes him beyond the wall he meets the Mephi, those who roam around naked, living as part of nature without the order of Onestate. Seeing her inspire them, the once rational D-503, now proclaims the need for revolution.

‘Everyone must absolutely go mad, and as soon as possible! This is crucial! I know it is!’

Love as an End in itself in Never Let Me Go

Once again, Never Let Me Go is different from most dystopian novels in that the clones think inside the system. Unlike most protagonists, they never try to bring it down. What they are acting for is love and love alone. In a system that uses them for organ donations they try to extend their time together through a legal loophole. But, though they might not want revolution, they are going against the normal bounds of the system that only gives them a short lifetime. They go to Madame, one of the founders of Halisham, believing that she can decide whether they can have a deferral and delay Tommy’s final donation.

During their childhood creativity was emphasised and Madame collected their best works for, what they called, her Gallery. So they see art as the means by which they will be judged on compatibility: on whether or not they deserve a loophole. Because Tommy struggled with creativity and never produced artwork worthy of the Gallery, he now painstakingly produces pictures to show Madame. They hope that what he’s produced will match Kathy’s art so they can have a few years to be together.

Acting to Change his Life and the System in Fahrenheit 451

Whilst Never Let Me Go is an anomaly in that the clones never try to bring down the system, in Fahrenheit 451 the main goal is for the system to be reformed. It’s different from the other novels because, though Montag acts in the hope of getting something better for himself, there’s no sense of hope in terms of love. He rebels against a system that burns books by stealing the books he’s meant to destroy and reading them. He wants to find deeper meaning but doesn’t have the ability to understand what books are saying. He goes to Faber, a former professor, believing that he can explain what is missing in the world and how Montag can try to find it in books. Faber explains that good books are one of many things that are valuable because they have depth: they don’t simply show the easy surface but the difficulties of life.

‘This book has pores…the more pores the more truthfully recorded details of life per square inch…good writers touch life often…the mediocre ones run a quick hand over.’

But Montag doesn’t just want to find meaning for himself. Like most dystopian protagonists, he understands that real freedom can only come through trying to enlighten others and ultimately reforming the system. When Faber argues that they can’t make people think, Montag tears pages from the Bible he’s brought to Faber. He only stops when Faber agrees to teach him more. Montag’s conviction means that Faber decides to go to a publisher, he knows, to print copies of the Bible. Montag, himself, aims to act against the firehouse system from within by planting the books he’s stolen in firemen’s houses. Although the other firemen realize he is a rebel, he manages to plant one book in the house of a fireman whilst trying to escape.

Hope’s Failure

The individual’s battle against the system shows there can be hope for change. But the system has all the power. Most of the time there is no possibility of reform however much the individual tries to do something. Those that attack the system are punished. So for hope to prevail, even partly, there needs to be some force acting alongside the individual. In Never Let Me Go, the clones only try to improve their own lives but most protagonists strive to reform the system and be part of something bigger. These endeavors only work if there is a strong revolutionary force behind them and, even with them, hope is only ever partly fulfilled. Most dystopias invariably end with loss as the individual’s hopes are never fully realised.

The Loss of Hope in Never Let Me Go

In Never Let Me Go the clones’ hope to get more time together is defeated. They thought that if they brought their art to Madame, they could prove their love and get a reprieve. But Madame stresses that she can’t give them a deferral. All they tried to do at Halisham was use art to prove they had souls, to show that they deserved a better upbringing. The way the system works means there was never a possibility of even a limited amount of freedom. People expect a cure for disease; they want organ donations so they refuse to see clones in the same way as humans. Faced with the loss of all their hopes Kathy questions why they were given so much if they were never going to be given a chance to really live.

‘Why train us, encourage us, make us produce all of that? If we’re just going to give donations, and then die, why all those lessons?’

In a society that uses the word ‘complete’ to suggest that clones make a noble sacrifice, she stresses that they ‘die’ to underline everything they’ve been denied. The loss of hope means that for the first time Kathy voices her hatred of everything the system has taken from them. But there’s nothing else they can do. All their hope rested in the system, in a possible loophole that might have given them more time together. There is no suggestion that a rebellious force exists and even if it does they never consider looking for a way to bring down the system.

The novel ends with complete despair. After their meeting with Madame, Tommy is furious that there is no possibility of a future together but all he can do is accept it. When he dies, after his fourth donation, Kathy loses all hope for something better. In this society clones either volunteer to be a donor or are given notice. For the past few years her skill as a carer to donors meant that Kathy was exceptional in that she hadn’t become a donor yet. But now she volunteers for this role. In the end, there’s no way to defeat the system.

The Destruction of the Individual in 1984

Hope fails yet again in 1984. Unlike the clones, Winston and Julia don’t just hope to love each other for as long as possible, they also try to change the system by joining the Brotherhood. But the nature of a surveillance state means their discovery is inevitable. O’Brien, their contact to the Brotherhood, is a spy for the Party and has been watching Winston for years. In this society, the system is so powerful that they use the idea that a group like the Brotherhood exists to capture rebels. Winston is tortured by O’Brien until he loses both his love for Julia and his own beliefs. He is taken to Room 101 and confronted with his worst nightmare. Faced with the prospect of rats attacking him, he gives them what they want, urging them to torture her instead.

‘Do it to Julia! Not to me! I don’t care what you do to her. Tear her face off. Strip her to the bones.’

After this betrayal their love is over. With her he hoped that he had something that the Party could never touch, something that was part of him being an individual. But the Party succeeds in ensuring he has no real ties to anyone.

This is a system that can make you say or do whatever they want. Winston’s hope that as part of the Brotherhood he could help change the system for future generations is completely futile. O’Brien makes Winston confess that the truths he once knew are simply false memories. He tries to resist but under torture, he is ready to say yes to any of O’Brien’s promptings: to agree that O’Brien is holding five fingers up even if the real number is four, to stress that their state, Oceania, was always at war with Eurasia.

Winston had hoped that he could be part of the process to defeat Big Brother. Instead he is tortured into total acquiescence to the Party. But he doesn’t just become an automaton without a thought of his own, he reaches a point where he begins to love Big Brother. Orwell shows how everything that made Winston an individual and a rebel against Big Brother is destroyed. There is no hope that the individual can resist such a system.

The Need for a Force acting alongside the Individual

But what if the Brotherhood could be reached, could the proletariat be roused, could there be some form of change? In We the individual acts against a similarly ruthless state to help a rebel force and some change is achieved. But hope is never fully realised, highlighting the entrenched nature of the system. Although there is some force for change, it is either only partly effective or can only increase the possibility of reform. So it’s not just about whether hope is realised or not. In some novels, what matters is whether hope is still a possibility by the end.

Hope Partially Fulfilled in We

In We hope in love fails but hope for reform is partly realized. By the end of the novel, D-503 no longer believes that he and I-330 can be truly together. However, the Mephi, the rebel force, have some success in their attack against the regimented order of the state. They destroy the Benefactor’s machine that kills opponents, disrupt the scheduled hour of eating and bring wild nature to the mechanized city. Hope for change is partly fulfilled but this isn’t the protagonist’s ultimate hope. There are times when D-503 has truly wanted rebellion. His greatest desire, though, is to be an individual and be with I-330. He wants what revolution will bring but is terrified by revolution itself. When the rebels break through the wall surrounding the city, he is scared by the chaos they’ve caused.

‘The city was strange and wild, the triumphant clamor of the birds would never cease – it was Doomsday.’

However the chaos is not the only reason D-503 cannot appreciate or justify revolution. Before the rebels attack he is taken to the Benefactor, the leader of OneState, who makes him believe that I-330 is only with him because he is the builder of the INTEGRAL. Whatever the circumstances D-503 would have hated the dramatic changes revolution would bring, but some part of him would have appreciated the possibility of the system changing if he believed that this would allow them to be individuals together. Instead, through the State’s influence, he is consumed by doubts about her love.

As the rebellion rages he rushes to her room. It’s here that he finds pink tickets, the exchange value for sex, with another man’s initial. She stresses that she just wants to be with him, but he’s still convinced she’s only using him for information. Having lost any hope in love, he volunteers for the operation, the procedure that removes feelings. Ultimately, like Winston, he becomes an automaton. He doesn’t recognize her as she is executed in front of him.

We concludes with the rebellion continuing. On the west side of the city people live according to whatever rules they want. This partly fulfills the hope D-503 once had that they could be individuals and be truly together. At this point though, he doesn’t believe in love and cannot stand the chaos of revolution. What the rebellion does do is partly fulfil the hope of I-330 and the rebels for the system to be destroyed. But it’s only a partial success. The government is still at war with the rebels, the machine has been repaired and a temporary wall is being rebuilt. However, the fact that the rebels hold part of a city that was once so ruthlessly controlled shows how far this society has come, even though on an individual level hope is crushed for D-503.

Hope Heightened in Fahrenheit 451

Fahrenheit 451 is different from We in that the ending shows a greater possibility of things changing rather than a hope that is partially fulfilled. This is not only because a large rebel group exists but a cataclysmic event occurs that has the potential to make people reassess the world around them. At one point, though, Montag’s hope that he could help destroy a system that burns books utterly fails. His books are discovered, his wife testifies against him and his house is burnt down. The system seems to triumph. He becomes a fugitive on the run with no access to books and no means to change the system from within.

But unlike most protagonists, his hope survives and changes. He escapes to the Book People, a community of former professors, who hold on to books in their minds, waiting for the moment when books can be written again. They believe that when the never-ending war is over people will want something more meaningful. Hope for Montag now is in being one of them, in keeping information safe for the future in this way.

‘[he will be] one of thousands on the road, the abandoned rail tracks, bums on the outside, libraries inside.’

There is a greater sense of possibility here because this is not just Montag, Faber and his small network: this community is one of many waiting for the moment where they can truly spread their knowledge. However, there are obvious limitations. This is a more philosophical force than the Mephi in We. They have no idea when the war will end, when any of this can be accomplished. The reason the government lets them exists is because their hope is less concrete. For now they can’t actively do anything.

But a few moments after Montag’s escape an atomic bomb hits the city. It is this cataclysmic event that really heightens the hope of change. There is now a real chance that people will listen, that after such loss they will find some meaning in the books the Book People hold within their heads. However Seed, a literary critic, stresses that though ‘there are connotations of hope…[Fahrenheit 451] has been criticized for expressing only a vague optimism.’ 6 There is still a sense of the power of the system given that the novel ends with only the possibility of hope being realized. Nonetheless, for hope to still exist by the end of a dystopian novel is a positive outcome. This is more than ‘vague optimism’. As Montag and the Book People journey to the devastated city there is a greater hope that change will happen.

Dystopia centres on the individual’s hope against the power of the system. But what so many protagonists need is love or some other catalyst to make them act against the state. Without something pushing them forward they would be like the rest of society: too scared or too passive to do anything but accept the state’s directives. For some, it’s only when they’re unable to find fulfillment in love that they recognise how much society is denying them. In Winston’s case, he hated the state before he met Julia but his defiance grows stronger as he falls for her. Love isn’t the only catalyst. Montag acts because another person makes him confront how unhappy he is with the world around him.

The individual sees past the state’s ideology. But for hope to still exist by the end of the novel there needs to be a force for change. The militant force in We ensures that hope is partly realised, whilst the existence of a philosophical force in Fahrenheit 451 combined with a life changing event heightens the possibility of reform. Without a sizeable group rebelling against the state, there can be no chance of change. People need to come together unified against the state, especially as something significant could occur that would make the passive majority consider defying the system. Ultimately though, hope is only ever a possibility or something partly realised. This underlines the truly dangerous and restrictive nature of a system whose framework cannot be easily overcome. In the end, the fact that hope exists even in the most oppressive societies shows us that humanity’s capacity to rise has not become completely defeated.

Works Cited

- Orwell, G. (1954) 1984 London: Penguin ↩

- Zamyatin, Y.(1993) We London:Penguin ↩

- Bradbury, R. (2008) Fahrenheit 451 Hammersmith:HarperCollins ↩

- Ishiguro, K. (2005) Never Let Me Go Croydon: Faber and Faber ↩

- Toker, L, and Chertoff, D. (2008) ‘Reader response and the recycling of topoi in Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go’ in Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas, 6, 166 ↩

- Seed, D. (2015) ‘Fahrenheit 451 in Context’ in Ray Bradbury Illinois:University of Illinois Press, p.111 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Thank you, that was a really good roundup and distillation of those books.

One underlying message reoccurs in all of these, and that is hope. <3

I think these books are quite simply based around the common theme of overcoming extremism in any form, and hope as its red line.

The key theme that I pulled from Fahrenheit 451 is the difference between the masses who have their minds managed on a daily basis by the carefully controlled TV output, and the minority that crave knowledge/creativity/culture and question what’s going on around. Who is happiest and more fulfilled? It’s a dilemma.

No. it’s not.

Great article and Fahrenheit 451 is a great novel. It had been a long time since I read the book but reading it again what struck me was the truly existential nature of the book. While it is billed as science fiction, it is really an exploration of identity and reality coupled with a reminder that the unexamined life really is one not worth living.

It was at the end of the 60s when I was only half-way through my teen years, that I first read this book. It was a good time to read it; it spoke loudly of the perils of apathy, ignorance, materialism and conformity. I didn’t see it then – and still don’t – as science fiction, any more than Orwell’s 1984 was science fiction. Farenheit 451 owes a great debt to Orwell’s work, and can be seen as the post-atomic version. Both show the enervating effects of creating ‘happiness’ and contentment by removing disturbing ideas; spiritual lobotomy by excising ideas that may vex us.

And that is what appals Montag when his wife, Mildred, attempts suicide. It isn’t the callousness or indifference of the technicians which affects him so much as the realisation that despair and spiritual lassitude have become so commonplace. Because something terribly fundamental has been lost.

The idea that books – stories – nourish us collectively is what grabbed my attention.

Enjoyed the book, but thought it was a bit short and maybe didn’t develop some of the themes/characters as much as it could have done.

Good article indeed. I read this book a few years ago and thought it so uncomfortable I have never gone back to it.

It’s true. Even though Montag suffered and was run out of town, he was fulfilled in a way his wife wasn’t. There was some part of her that knew that otherwise she wouldn’t have kept overdosing on drugs. In ‘1984’ Winston does become an automaton in the end, but his greatest happiness comes when he defies the state.

It is strange how the world is coming to resemble in ways some of those disturbing dystopian novels life F451, Brave New World and 1984.

Is it possible for a book to be too dystopian?

“We” is a superb work of science fiction.

This. I don’t usually go for sci-fi or dystopia books — I didn’t even like Brave New World very much — but I loved this one, even if it was sometimes hard to understand.

I agree. The protagonist had one of the most distinctive literary voices I have ever seen

This was a very challenging read; in many ways I feel a second read will be necessary to better comprehend this book.

Nice read. If you’re thinking about reading 1984 after reading this post, please do. Reading this book can help you become a more critical thinker, especially when it comes to politics. So many of the words, phrases, and ideas from this book have become part of our shared culture and vocabulary, for good reason.

What amazed me most about this book is that it was written in 1949.

I am thoroughly disturbed and stressed out after reading 1984. What a remarkable piece of prophetic writing.

This is no more science fiction, it is a documentary.

In Never Let me Go, I loved how pieces of information were slowly revealed as the narrator tried to piece together memories from her past.

A great article and analysis. Thank you. In my opinion as long as there are books and readers, there will be individuals who think for themselves, even if we don’t always express those thoughts openly.

For terrifyingly accurate idea of the future, forget these and read C. M. Kornbluth’s “The Marching Morons”.

I enjoyed this a lot – thank you. I wonder what today’s teens are going to be like 20 or 30 years down the road. Will it be like any of these YA dystopias…

Strong piece. Authors don’t write dystopian works to escape the real world, they write to face it.

It’s so true. People talk abut books being escapist but most books, even if they’re exploring a fantasy world, force us to confront issues that face us in the real world. Dystopian novels are just more blatant about it.

I am super inspired to write a dystopian novel now. Thank you for the inspiration.

I love Fahrenheit 451 – I read it at school when I was kicked out of English class for talking too much. I was forced to sit in the corridor, next to a book storeroom where I find it housed. I took it home and read it that night. Seems strangely ironic to me now…

I have to teach Fahrenheit 451 in class since I am a teacher. It is an ordeal since the book is obsenely bad. If you want to learn how to misuse metaphors and how to suffocate a plot with dumb imagery this is your book.

I love I-330 more than ever, ever, ever. What an absolute queen-grandmother of all the sci-fi princesses running around these days.

I love her too. She is a truly formidable character that is stronger than a lot of female literary characters today. The Bolshevik idea was that men and women were supposed to be equal, even if this didn’t work out in reality. So I-330 is, at least in part, based on those ideas.

Classic dystopian fictions are the best.

1984. I had heard so much about it. I had expected it to be path-breaking, earth-shaking and all sorts of awesome. But on finishing, my reaction was hardly anything more than Meh!

Really, really good article you have pieced together here.

Many of the ideas in these books are still relevant today, unfortunately.

What’s scariest in Never Let Me Go is the idea of people living the way they’re “supposed to” without ever having one real thought of freedom their entire life.

I knew 1984 was a book I needed to read, from the first time I heard it called one of the best books ever written.

I consider We to be the Citizen Kane of totalitarian dystopias.

Favorite line in these novels are: “Theory, hell,” said Montag. “It’s poetry.”

While the language in “Fahreheit 451” is obviously dated, it still resonates. I feel that the emptiness that Bradbury’s future society flounders around in is well conveyed in the OD and stomach pumping scenes. The depiction of the murderous joy-riding kids is both evidence of society’s numbness and attempts to -feel- anything. Montag’s thought process as he drifts along river waters goes back to the “Dover Beach” poem he read to Millie and her friends. He’s going with the “faith” bit. And the atomic bomb detonation instead of instilling despair, instills hopefulness–something not felt for a long while….

These books offer hope that we, as a people, come together, and will survive. More relevant than ever now.

Isn’t that a nice thought for any reader to take away from a book!

Kudos, read read. Dystopia allows us readers to see it is possible to fight back against systems who care more about profit and the accumulation of power than the inherent value of all persons. When characters engage in an act of compassion or empathy they help dismantle the system which oppresses and abuses them. The smallest acts of compassion let’s good breathe, however briefly.

That is how we outlive our circumstances and how we find hope in the hopeless.

Lovely article!

All stories are based in hope and the ones without it are disingenuous and maniuplative.

I found F451 worth reading for its imagery.

I never knew “We” existed until recently. It goes to show, one thing, or book, leads to another – always. 🙂

I know – I also only discovered it recently. It’s such a shame that so many non-english books so often don’t get the attention they deserve.

There is always joy and hope in dystopian fiction, even when tsunamis wipe out one-fourth of the world or technology is gone.

I never finished Never Let Me Go, but reading this article has definitely reignited my interest in it. a very enjoyable and interesting read, thank you!

A flash of hope is all they need to live and make change.

A nice breakdown of the concept founded on a fundamental human drive – hope. The dystopian novel/narrative is one that continues to resonate with readers as we are yet to create a society that transcends us to a utopic state. These narratives are also fantastic looking glasses that reflect the socio-cultural context in which they are developed. The failure for hope to succeed is a timely reminder that we need to consider how is hope driving our own society?

The movie Brazil is a great example of exactly what these movies also show – Love is the reason the individual tries to escape his distopia after showing the audience how futile existence is – it’s a great movie!! I won’t give away what happens…

A good essay, well thought out.

Great article and even better imagery to go with it.

I read 1984 in high school and was taken aback in terms of how terribly wrong mankind can emerge and how disturbingly deep humanity can stoop. I also happened to read Fahrenheit 451 more recently and was surprised to learn how prevalent this theme remains. After writing on this very topic, the readers have alerted me to other dystopic novels I have never and would never have known otherwise. I am certain it is bound to resurface here, there, anywhere–if it is not already lurking around unnoticed. Hoping to be continually reminded of the probability.

Love a good dystopian story! Out of the ones you mentioned, Fahrenheit 451 is my favorite.

Good job on this article! Love how you highlighted the theme of hope in each of these works. It’s really made me want to read all these works and explore the dystopian genre all over again.

The word ‘dystopia’ gives me a nightmare, I am so afraid of uncertainty and fear!

This is a good read, thank you!

I see a similar parallel with Brave New World, where hope fails with the protagonist’s actions at the end. Hope is just a stepping stone, however it needs to be combined with optimism and effort backed by a like-minded rebellion to defeat the system. It takes a lot of faith in humanity to achieve this.

This is a great article – thank you! I think that any hope Winston has of a reality other than the one the Party has constructed is feeble. Afterall, he knows early in the novel that ‘thoughtcrime is death’. He also clings to the belief that ‘if there is hope, it lies with the Proles’. Still, his efforts to reclaim his memories of the past, and his relationship with Julia, are acts founded on hope, however futile.

I think perhaps a key distinction should be made between dystopian novels written for adult or general audiences versus those written for young adults. In the latter, we tend to find the hope discussed here in this essay somewhat more rewarded than the hope found in the former. Although young adult literature has its pedagogical reasons for wanting to offer its readers hope, it seems to me that we find two common results anyway: loss of hope from too much dystopian reading (including what’s on the news) or a loss of initiative due to an expectation that things will resolve themselves anyway. The older dystopian narratives, however, pattern themselves after Zamyatin’s hopeless template due to the historical lessons of the 20th century.

I am not too sure if your goal was to do an analyze the theme of Hope in these texts, but your article felt more like a specific synopsis with mentions of how hope either exists or does not according to specific events.