Elfen Lied’s Eugenic Underpinnings

Elfen Lied is a famous ultraviolent horror manga from the early 2000’s. Although the manga did not receive an official English translation until 2019, the series still garnered a large English-language following owing to the release of a lavishly-rendered anime series in 2004. This series tells the story of the Diclonius, a race of mutants who look like pretty, fair-haired girls with little horns on their heads. These mutants possess a weapon in the form of magical invisible hands called vectors, which they use for everything from manipulating objects to destroying buildings and people. They also seem to have an instinct for killing any human beings they come across. The series has long fascinated fans for its depictions of violence, and the savagery of humans toward those who are different from them. Unfortunately, it also paints the slaughter of those supposedly “inferior” in the most glamorous and sympathetic possible light. It thus stands as a modern, science-fiction take on eugenics, the belief that only certain “desirable” humans should be allowed to contribute to the gene pool 1.

The True Meaning Of the Diclonius

The human characters of Elfen Lied, with a few notable exceptions, generally treat the Diclonius with suspicion and loathing. Most humans either bully the Diclonius or lock them away in top-secret laboratories to experiment on and torture. As such, the series is generally understood as a critique of how people treat those who are different. This interpretation only scratches the surface, however. To say that Elfen Lied is a story about racism or simple intolerance, as some fans have, misses a few key points. First of all, unlike in most real-world examples of discrimination the Diclonius pose a physical threat to human beings, insofar as they try to murder them. Second of all, the “happy ending” to the manga includes a reassurance that scientists and soldiers have eliminated them forever. The manga makes it clear that the Diclonius are victims of circumstance, but destroys them regardless.

Furthermore, the scientists of Elfen Lied point out that the Diclonius grow and develop in a fairly predictable way. Most of them look and act like normal children, albeit with horns, until somewhere between the age of three and ten. At that point, they gain both their vectors and the urge to kill people. In this respect, the trajectory of the Diclonius seems eerily similar to that of people with certain neurological abnormalities. For instance, patients with the genetic disorder Huntington’s disease live normal lives until roughly middle age. When they’re somewhere between thirty and sixty years old, their nervous system starts to decay, causing them to develop dementia and lose control over their personalities, movement, and bodily functions 2. Other genetic disorders, like Tay-Sach’s disease or untreated phenylketonuria, cause severe brain damage or death to young children who are just a few years old 3 4. Tellingly, Elfen Lied also makes it clear that all the problems the Diclonius have stem from abnormalities in their brain structure. All in all, the Diclonius seem to represent children who suffer from severe mental illnesses or other neurological conditions. In a disturbing twist, Elfen Lied also seems to be arguing that such children are not fully human or worthy of life.

A Note About The Word “Severe”

Common activist slogans–such as the familiar “1 in 5 US adults experience mental illness each year 5“–seem to imply that all mental illnesses are more or less interchangeable in their impacts. The reality, however, is that mental health problems, like all health problems, have a scale of severity. For instance, although there are individual differences, as a general rule mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety, are not as disabling as psychotic disorders. Many scientists now think that psychotic episodes–which entail hallucinations and difficulty determining what is real–damage the brain in some way 6. Indeed, the more prevalent psychotic symptoms are in a particular patient’s illness, and the longer the patient goes without treatment, the more debilitating that illness will be.

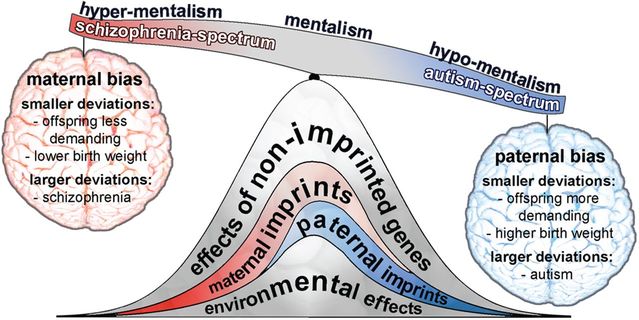

Overall, schizophrenia seems to be the most disabling of the common mental illnesses. Autism, another common neurological condition, shows a similar severity. According to one study, patients with either of these conditions have significantly fewer children on average than even patients with many other types of mental disorders 7. They also tend to die younger. For instance, a study from Sweden found that the average life expectancy for a patient with schizophrenia is more than ten years less than that of the general population 8. Another Swedish study found that patients with mild autism have an average life expectancy of less than sixty years. Those with severe autism, meanwhile, often live less than forty years 9.

Most people seem to intuitively distinguish between those who have just any mental health problems and those who have severe mental health problems. Nobody would ever dream of suggesting, for instance, that someone who suffered occasional bouts of depression or panic attacks deserved to be permanently locked up in an institution or killed. It’s much easier to see those whose mental problems prevent them from living a normal life as not fully human. The challenge, then, is to recognize the humanity in those with severe mental health problems, and to help them become the best members of society they can be, given their capabilities. It’s a delicate balance that requires a lot of thought and effort. What a series like Elfen Lied does, by contrast, is pander to humans’ innate fear of those with abnormal or antisocial behaviors and validate their desire to see them eliminated. Over the course of the manga, and to a somewhat lesser extent the anime, the series undermines the Diclonius’ humanity in a number of key ways, some of which are more blatant than others.

Little Monsters

Right from the beginning, Elfen Lied attempts to drum up fear of the Diclonius in its viewers. More often than not, the first thing the audience sees a Diclonius do is murder someone, often by tearing them apart, blowing them in half, or some other such grisly method. Although the series pays lip service to the idea that Diclonius can avoid killing humans if treated kindly, the manga in particular makes it clear that all Diclonius have an innate urge to kill humans that even the best of them only barely suppress. In the manga Lucy, a teenage Diclonius who serves as the series’ central character, explicitly identifies her urge to kill as “the voice of my DNA, calling out my instincts within me[…]” The anime is more subtle, but even there she admits to her friend Kouta that, “You have to understand, I was born to put an end to human life.”

Some Diclonius take their brutal nature even farther than Lucy does. One of them, a five-year-old girl named Mariko, has lived her entire life in an armor-plated holding tank under top security to prevent her from killing the people who work in the laboratory. Her only human contact is with a researcher named Saito, who interfaces with her via a screen. When Mariko is finally released and gets a chance to speak up, she admits that she has always seen killing people as a fun game. Strange as it seems, her situation has at least some basis in truth. Some of the earliest behavior-modification experiments on human beings were performed on children who had been locked up all their lives for injuring themselves.

All three [of the children in the study] ferociously pummeled their own faces, especially their ears, with their fists, or slammed their heads into whatever sharp, hard edge was nearby. During one ninety-minute period, John had been observed striking himself 2,750 times. The faces and heads of all three children were a road map of scars. On the day Linda was brought in to [the University of California at Los Angeles], she had blood leaking from one ear. None of the children could talk; the violence they turned on themselves was the only message they seemed capable of sending to the outside world.

[…]All three had started hurting themselves as toddlers and had since been subjected to the same last-resort method of control: physical restraints, twenty-four hours a day. 10

Of course, in real life most people with severe mental health problems are basically harmless. However, a small minority (who unfortunately tend to receive disproportionate media coverage) engage in fantastically disruptive and dangerous behavior. In Ithaca, New York, a psychiatric patient named Debbie Stagg first made the news when she performed a Cesarean section on herself. Many years later, she appeared in the news again for stabbing a police officer to death 11. Spectrum News, which gathers news stories about autism spectrum disorders, once profiled an adolescent boy who has been hospitalized for violent, destructive tantrums. One of these tantrums lasted for three hours 12. In Unorthodox, a memoir written by a woman who left the Satmar Jewish community as a young mother, the author recounts the difficulties of growing up a family with hereditary mental illness. She describes how, at one point, her cousin became aggressive during a psychotic break.

One night Baruch got out [of the room he was being kept in] somehow, smashing through the door with his fists, emerging with bloody gashes on his arms. His screams were guttural; they burst endlessly out of his throat like those of a wild animal in pain. He destroyed everything he could get his hands on. They had to wrestle him down in the the hallway, the paramedics, and sedate him. 13

In the medical community, it’s generally understood that severe mental problems increase the likelihood of aggressive behavior. However, this aggression takes many forms and is in no way an inevitable fact of life for the mentally-ill. For instance, one study suggests that schizophrenia patients become aggressive for two major reasons. Patients may suffer delusions of persecution, which cause them to irrationally view other people as enemies. They may also have comorbid conditions such as drug use and psychopathic tendencies, the latter of which might induce them to deliberately control and intimidate others 14. In other words, for many of these patients, their decision to harm others is a choice. Elfen Lied, though, steamrolls right past the ideas of free will and choice, instead treating violence and murder as something that the Diclonius just naturally do.

Additionally, none of the scientists in Elfen Lied seem interested in training the Diclonius out of their murderous tendencies via behavior modification therapies or medication, both of which have a long history of treating disruptive mentally-ill patients in real life. The original applied behavior analysis (ABA) programs, developed by the scientist O. Ivar Lovaas to treat autistic children with behavior problems, were extremely austere. Researchers sometimes employed techniques that would nowadays be seen as abusive–like slapping young children across the face or shocking them with cattle prods. Lovaas justified these tactics by claiming that he was simply doing whatever it took to help the children learn 15. Given Elfen Lied’s rather unhealthy obsession with showing young girls getting abused and humiliated, it’s all the more striking that no such program seems to exist for the Diclonius. If the series can show children being murdered–often in gruesome, lingering ways–why not show them being hooked up to electrical wires that shock them every time they deploy their vectors around humans, or, conversely, having cookies and candy shoved roughly into their mouths whenever they refuse? The possibilities are endless yet almost totally unexplored. Instead, the only reason the scientists seem to want to study the Diclonius is to find a way of killing them more effectively.

A Closer Look at Lucy and Nyu

Lucy, the main character of Elfen Lied, is a young Diclonius somewhere between the ages of fifteen and eighteen. At the beginning of the series she escapes from the research lab where she is being held and arrives in Kanagawa Prefecture, which happens to be the home of her childhood friend Kouta. At the beginning of the series, Lucy comes across as quite sadistic, killing with little thought or remorse most of the time and sparing only Kouta and his close companions.

Lucy first met Kouta when they were both children. Before meeting him, she lived in an orphanage with a lot of other children who called her a freak and bullied her without mercy. On one occasion she befriended a stray puppy, only for the other children to take the puppy away and beat it to death in front of her. In retaliation, Lucy killed them and ran away–the first time she had killed anyone. Interestingly, the children’s specific motive for killing the puppy was to get a reaction out of Lucy, since they thought her lack of emotion was creepy. She continues to show little expression throughout the series, even years later. Tellingly, a lack of emotional expression–what doctors call “flat affect”–is a common symptom of various neurological disorders, including autism and schizophrenia 16.

As Lucy is fleeing from the lab, a shot in the back of her head causes her to develop an alternate personality known as Nyu, who has no memory or knowledge of how to use her vectors. In the beginning of the series, Nyu acts very much like a toddler, with no understanding of clothes, toileting, common food items or even most words. Kouta and Yuka call her Nyu because that is all she can say. She becomes more capable as the series goes on, though she learns more rapidly, and shows more genuine kindness and social skills, in the anime than the manga.

Throughout the series, the character shifts between the personae of Lucy and Nyu more or less as the plot demands. Often, minor visual cues such as posture, facial expression, and eye shape clue the audience in to which one she is at any particular time. Particularly in the early stages of the series, this transformation happens with very little warning or buildup. For instance, at one point Nyu hits her head while cleaning the floor and becomes Lucy, thus ratcheting up the tension of what had previously been a peaceful, normal scene. In this scene, and many others like it, the fear of horrific violence striking at almost any time captures on a small scale what life with a violent psychiatric patient is like. One mother, whose young adult son has a severe autism spectrum disorder, puts it like this: “Most of the time [my son] is a sweetheart, but like the flick of a switch, he can start to rage, breaking everything in his path, including me 17.”

Furthermore, Nyu, particularly in the first half of the manga, is a far cry from the innocent, harmless soul she’s often made out to be. In the anime, at least, she appears to genuinely care about the other characters, attempting to feed the other girls rice and comfort them when they’re sad. In the manga, by contrast, much of her behavior is downright pathetic and creepy, and her one saving grace is that Lucy is so much more dangerous. She openly throws herself at Kouta, tries to make him touch her breasts and, at one point, jumps into the bath with him so she can hump his leg. She also sexually harasses the other teenage girls, groping their breasts and sticking her hands up their skirts. As such, it’s hard to imagine anyone wanting to be around Nyu in real life, let alone teenage girls who have histories of abuse (including sexual abuse). The irony is that in real life Nyu herself would be exquisitely vulnerable to sexual abuse. Studies show that women with learning disabilities are among the most likely to be sexually abused 18. The fact that this abuse often comes at the hands of caretakers makes Kouta’s willingness to play along with some of Nyu’s advances particularly troubling.

A Parent’s Worst Nightmare

Severe mental illness tends to put a strain on not just the individual patient, but also that patient’s family. Even if the patient has no track record of unsafe behaviors, the cost of their medical bills and treatment programs can really add up. The relatives of those with more serious behavioral problems fare even worse. In Elfen Lied, the challenges of parenting a violently-ill child are taken to their furthest extreme.

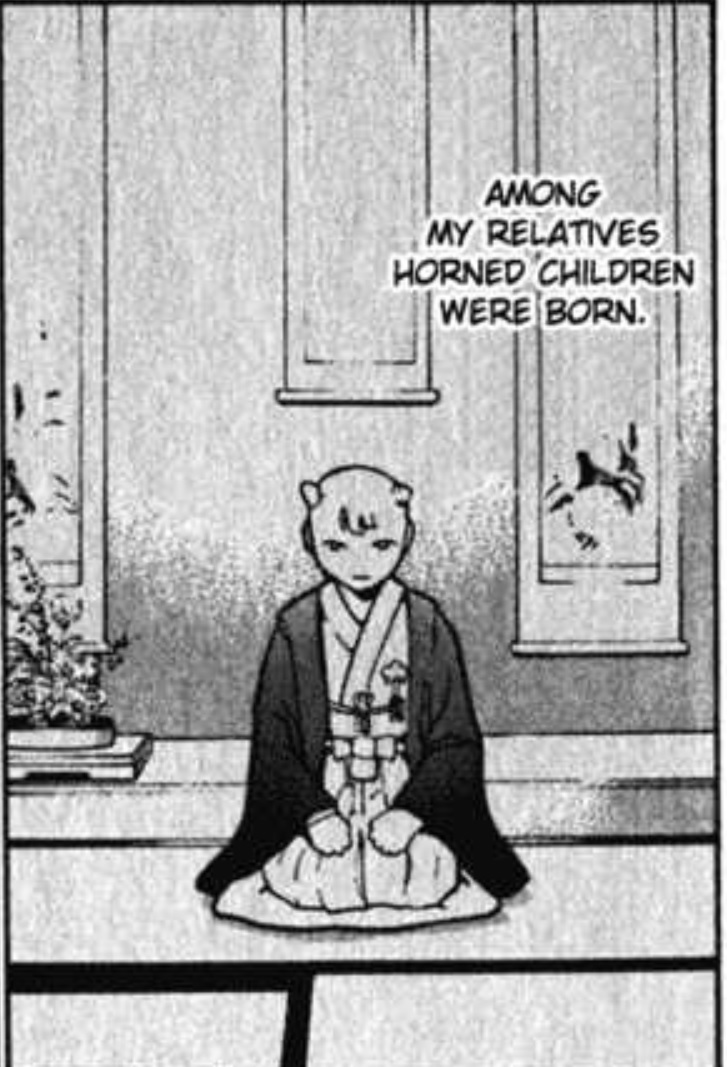

Kurama’s backstory seems designed to bring this dilemma to the forefront. Kurama is a research scientist who is attempting to study and, ultimately, put an end to the Diclonius. He is also Mariko’s father, and has made many sacrifices to keep her alive, even if she’s not living much of a life at all. Years ago, when both his wife and that of his assistant Oomori were pregnant at the same time, the younger Kakuzawa used to taunt them by saying their children would be Diclonius. At the time, they laughed off his pronouncements, as Diclonius births were thought to be very rare. However, both of their wives did ultimately bear Diclonius as a consequence of their husbands’ prior contact with vectors. Interestingly, the manga explains that Kurama’s wife was infertile, to the point that she had to conceive Mariko using in-vitro fertilization and deliver her via Cesarean section. In real life, one of the biggest risk factors for mental disorders, other than genetics, seems to be complications of pregnancy and childbirth 19 20. Children conceived with the help of assisted reproductive technologies also show an increased risk of learning disabilities 21.

In a scene at the hospital, Oomori attempts to dissuade Kurama from killing his daughter by insisting that “Horns or no horns, she’s my daughter and I love her!” Kakuzawa dismisses his pleas by replying that this “only means that in three years you’re the first person she’ll kill.” Kurama adds that: “When you consider the only eventual outcome, it’s better to kill her before she grows.”

Of course, in real life, nobody can predict serious mental illness or aggressive behavior at birth. Even within the same family, mental illnesses can look very different. For instance, the famous mathematician John Forbes Nash and his son Johnny both have had bouts of psychosis. However, Johnny’s psychotic episodes seem to be more severe than his father’s, and they also started much earlier in life 22. Many people with hereditary mental illnesses, even if they manage perfectly well, are reluctant to have children and risk passing on their conditions 23. One Finnish study found that patients with severe psychotic disorders have much higher rates of abortion, relative to all pregnancies, than healthy controls 24.

Furthermore, if a child does receive such a life-altering diagnosis, the very ambiguity about what the diagnosis means can cause family members considerable anxiety. In general, the only certainty of having a mental illness is that it will make one’s life, and the life of one’s family, more difficult. In previous eras, parents who produced a child with a neurological disorder like autism would have been told to place their child in an institution and forget about them 25, similar to the advice Kakuzawa Jr. gives to Oomori in Elfen Lied. The parents of Donald Triplett, the first child to be diagnosed with autism, were given just this advice. Still, they eventually pulled him out of the institution and set about helping him acquire the skills he needed to live a mostly normal life 26. In modern times, institutionalization may not be an option because the few remaining places have fewer spots available, and parents are mostly left to their own devices to get help for their children. One parent of a child with autism succinctly describes the stress and uncertainty that grips many such parents when their child is diagnosed:

Will he ever talk distinctly? Eh, maybe.

Will he ever learn to read and write? Let’s hope so.

Will he ever finish high school? Wow, slow down buddy! At this point we’re trying to help him survive pre-school without having meltdowns every day nor killing a classmate someday (not kidding, unfortunately). Then he’ll go to Special Needs school and-

Ah, yes, he will have to go to Special Needs school, I’m afraid. He’s very intelligent, but far too autistic to manage normal school. 27

In addition, Kakuzawa’s ultimate plan entails spreading a virus that will cause more Diclonius children to be born than humans. The horrifying way this plan is framed echoes a fear that rates of mental illness are increasing in real life. Some autism parents cite data showing that a greater proportion of special-education kids have an autism diagnosis as evidence that more children than ever before are showing extreme behavior problems and will need lifelong care 28. Even the furore over vaccines was driven by a fear of producing a child with behavior problems like those seen in the worst mental illnesses and disabilities 29.

Meanwhile, the sick children who can grasp the feelings of their relatives are left to feel like burdens. In Elfen Lied, Mariko believes, not without reason, that Kurama threw her away when he discovered her horns. She becomes all the more bitter and enraged when she learns that Kurama has been treating the innocent and gentle Nana as a surrogate daughter in her absence. In a landmark essay from the 1990’s, “Don’t Mourn For Us,” a writer and speaker named Jim Sinclair claims that, whether they admit it or not, many autism parents feel that “I wish the autistic child I had did not exist, and I had a different […] child instead 30.” By all appearances, this is exactly how Kurama views Mariko. To really drive the point home, around the time of Mariko’s death both the manga and the anime include a series of images featuring the happy life that she could have led with her mother and father, if only she had been a normal girl. Of course, the narrative implies, one can hardly blame Kurama for feeling this way. Who wouldn’t rather have a sweet and obedient child like Nana than one as vicious and out-of-control as Mariko?

Tragically, some people crack under the strain and end up harming themselves or their sick family members. One single mother in Ethiopia used to tie her severely-autistic daughter up for hours at a time, and had contemplated killing both her daughter and herself. Salvation came when was able to seek help at the nation’s only clinic for autistic patients in Addis Ababa 31. It’s perhaps fitting that, in the Elfen Lied anime, Kurama embraces Mariko and promises that they will be together forever just as the bombs that had been planted inside of her explode, killing them both.

What About Nana?

Nana is another young Diclonius, who seems to be somewhere between the ages of seven and ten. Innocent and unable to kill anyone, she stands as a counterpoint to most of the other, gleefully sadistic Diclonius. It’s established early on that Nana wants to be good in order to please Kurama, whom she calls “Papa.” In the manga her fondness for him crosses the line into a full-blown obsession, to the point that she asks him to take her as his wife and even allow her to bear his children.

All in all, Nana seems to represent the fortunate few who, despite having quite serious mental problems, nevertheless manage to succeed in work, relationships, public speaking and other areas of life. Real-world examples of this type of person include the likes of Temple Grandin, John Nash, and Greta Thunberg. These individuals, and others like them, are often used as poster children for what people with mental illnesses and neurological conditions can accomplish. Unfortunately, the public’s admiration for what a subset of people with mental illness have accomplished rarely translates to greater awareness of or empathy for those who have more significant impairments. The Nazi pediatrician known as Hans Asperger took this double standard to its logical extreme, publicly vouching for patients whom he deemed “educable” while blithely signing the death warrants of those who weren’t 32.

Compounding the problem, some people seem to deliberately divert attention away from those with more serious difficulties to those whose symptoms are more subtle. One website for autism parents ran an article on self-harm in autistic people without learning disability that explicitly states: “[I]nsofar as it relates to self-injury, autistic people without intellectual disability are underserved 33.” Another website counsels parents of severely-autistic children that “Your child may not be toilet-trained, but please be grateful they don’t know how to cut their wrists 34.” The implication seems to be that children who need more everyday assistance never self-harm (which is patently false) or are content and happy because they don’t know what they’re missing.

On the other hand, Nana herself encourages the humans and Diclonius to attempt to find common ground. When Kurama tries to kill Mariko in the manga, Nana intervenes and tells him that his job as a parent is to help her become a better person. In a similar vein, famous people who have a particular disability are often called upon to speak up for others who have the same disability, as they put a human face to the condition. Parents and other family members who see the famous person’s successes and accomplishments can draw inspiration from them, and cite them as evidence of hope for their own relatives’ futures.

All the same, the series never really uses Nana as evidence that Diclonius can learn to get along with humans. Instead, it treats her as the one glowing exception to the rule that Diclonius were born to kill humans. It’s telling that of all the Diclonius she is the only one still alive at the end of the story.

Cruelty For Cruelty’s Sake

Though Elfen Lied has few unambiguous “good guys,” it does have several recognizable “bad guys,” whom the audience is meant to hate and fear without reservation. The most prominent examples of this type of character are the Unknown Man and Nousou, both of whom appear only in the manga. The former is a bounty hunter who keeps a dismembered Diclonius in a box to enable him to track down other Diclonius, and who enjoys raping girls (Diclonius or otherwise). The latter is a scientist who oversees a laboratory that creates clones of Mariko using the salvaged bones and organs of Diclonius children. Both are clearly designed to be so horrible they make any other character they come into contact with look good by comparison.

Sadly, in real life, abject cruelty toward those with mental illnesses is all too common. Though abuse can come from anyone, those providing care to patients are a common culprit. One patient who spent time in a psychiatric hospital in the UK said that she was raped fifty times while under the influence of sedatives. “You are a second-class citizen so therefore it doesn’t matter so much. One time, 50 times, it doesn’t matter 35.” The more help the patients need, the more likely they are to experience abuse. At the furthest extreme are those victims that lack the skills to even communicate the abuse to their friends and family 36.

Sometimes, entire institutions may be implicated in abuse of their patients. In the UK, an undercover reporter at a long-term care facility documented staff routinely taunting and mistreating their patients, who had autism or other serious learning disabilities. Footage taken in the facility showed the staff insulting patients to their faces, sexually harassing them, stealing their belongings, and restraining them without provocation, among other things 37.

Oddly enough, not everyone who abuses patients in this way considers themselves to be bad people. One man interviewed by NPR, who pleaded guilty to sexually abusing a ten-year-old nonverbal boy, claimed that he never saw himself as an abuser, and that he genuinely cared for the child overall. His exact words were: “I wholly prided myself on doing a selfless job for people who are disabled and can tell you many nice stories about all the lives I touched in a positive way 38.” In Elfen Lied, Nousou demonstrates a similar type of cognitive dissonance. In order to fight Lucy, he creates an army of super-powerful Diclonius, whom he renders docile using a mind-control device plugged into their foreheads. This device forces them to obey his every command, no matter how wicked or dangerous it is. Through it all, he claims, against all logic and evidence, that he truly values and loves them.

The Dark Side Of Neurodiversity

The Kakuzawas stand as the main antagonists of Elfen Lied. The elder patriarch of the family, in particular, spends most of his time concocting schemes to capture Lucy. He intends to force her to bear Diclonius children and, thereby, become the creator of a new race of beings. It’s easy to assume, based on the German words and references that appear throughout the series, that Kakuzawa is supposed to be a Nazi of some sort. However, on closer inspection, he and his family seem instead to be caricatures of the more militant wing of the neurodiversity movement.

The neurodiversity movement, in broad strokes, is a social movement that views mental illnesses and neurological conditions through the lens of something called the “social model of disability.” According to this theory, people who have disabilities (physical, neurological, or otherwise) are just as capable as anyone else, and only an intolerant, ableist society holds them back from achieving their goals and living their best lives 39. The term “neurodiversity” is a play on the word “biodiversity,” insinuating that, just as ecosystems need all sorts of living things to stay healthy, human beings need all sorts of neurology 40. Most neurodiversity activism deals with autism spectrum disorders. However, similar attitudes appear in discussions of other mental disorders as well, and figure prominently in what has been called anti-psychiatry 41.

Although neurodiversity may sound noble, it comes with considerable drawbacks. The most obvious is that neurodiversity activists rarely have anything useful to say to those who suffer from the most severe mental illnesses, or their families. More often than not, their preferred strategy when confronted with such severe cases is either to deny that their problems exist, or blame those problems on someone or something else. One neurodiversity activist describes a trip he took to the home of one of his followers, whose son has a particularly severe case of the genetic disorder known as neurofibromatosis 42. When the mother admitted that many adults were afraid of her son, the activist replied simply: “But he’s awesome 43.” It didn’t seem to occur to him that adults may have good reason to fear this child, as according to his mother’s blog he is so abusive and wantonly destructive she can’t leave him alone even for a moment 44. Other neurodiversity activists claim that schizophrenia is a benign neurological difference. These people argue that schizophrenia patients in third- and fourth-world countries, with their strong sense of family and community, do much better than those in more individualistic first-world nations 45. However, many studies conducted in those same countries have thoroughly debunked such a claim 46.

Neurodiversity activists are especially suspicious of the medications and behavioral therapies normally used to treat the symptoms of severe mental illness, which they write off as inherently unethical and abusive 47 48. Some may suggest alternative therapies, though these are often fraudulent and unreliable 49. Most of the time, they simply argue that the mentally-ill and disabled would flourish if only they were given more accommodations and acceptance 50.

Neurodiversity relies on the notion that those with neurological differences are being oppressed by those without them, whom activists refer to as “neurotypicals 51.” Some go even further, and argue that neurodiverse individuals are simply better than neurotypicals. They may, for instance, engage in thought experiments of what life would be like if neurotypicals were in the minority 52. They may also sneer at famous people with neurological differences, like Temple Grandin, who have the temerity to point out the problems their conditions can bring or actively court a neurotypical audience 53. It is this version of neurodiversity that Kakuzawa represents. He believes that humans have been oppressing the Diclonius, and therefore the Diclonius ought to replace humans so they can live freely.

Towards the end of the manga, Lucy reveals that, despite his protestations, Kakuzawa is not a Diclonius at all, but only a human with horns. In real life, one common criticism leveled at neurodiversity advocates is that many of them do not actually have the neurological conditions they claim to possess. One teacher writing about autism and neurodiversity explains:

Many [neurodiversity] advocates weren’t diagnosed until adulthood–and in some cases were self-diagnosed. Professional diagnosis is based on survey questions and observational data, which those who are determined (for any number of reasons) can easily game. Self-diagnosis, as far as I can tell, is typically based on online surveys and/or identification with autistic characters in TV shows (e.g., The Good Doctor). If you’re a small-talk-hating introvert with all-[absorbing] interests and sensory sensitivities, it’s easy to make the diagnostic leap. YouTube videos of some of these adult/self-diagnosed people often show none of the typical signs of autism that even the highest-functioning of true autistics (e.g., Temple Grandin) exhibit: no unusual gestures or perseverative movements; no abnormal patterns of eye contact and intonation; no indications of canned or echolalic speech; no awkwardness or stilted speech or lack of fluency in conversational back and forth. 54

This attempt to downplay the struggles associated with severe mental illnesses and reframe them as benign “identities” has consequences. Most studies on autism spectrum disorders exclude, whether by accident or design, those with the most severe symptoms, and the proportion that do address such cases is decreasing over time 55. Initiatives designed to raise “mental health awareness” generally focus on college students or young professionals with transitory mood disorders such as depression. Meanwhile many patients with severe psychosis continue to languish on the streets 56. The lucky ones make their way to hospitals where they’re administered twenty-year-old drugs with a host of unpleasant side effects 57. The families of patients with severe intellectual disabilities, meanwhile, must act as their relatives’ full-time domestic nurses for their entire lives, all while worrying about what will happen if the patient outlives them 58.

It’s perhaps no coincidence, then, that the most cruel and vicious characters in Elfen Lied, including the aforementioned Unknown Man, ultimately work for and answer to Kakuzawa. As much as neurodiversity advocates claim to care about those with serious mental-health problems, they still contribute to their dehumanization in a roundabout way by failing to directly address their challenges. To be seen as fully human entails responsibilities as well as rights. At a minimum, the people that one interacts with should be able to trust that they will keep themselves safe; respect others’ rights, property, and boundaries; and give something back to society instead of just taking. By failing to provide a satisfactory road map to integrating those with severe mental illness into the wider society, neurodiversity advocates unwittingly affirm the view that they have no place in society.

Who’s The Real Hero, Anyway?

Although the villains of Elfen Lied are pretty easy to spot, identifying a hero is a much greater undertaking. Lucy herself can’t be a hero because she is too much of a villain. Still, it doesn’t make sense to call Kouta the hero either. Although he is probably the most central character other than Lucy, he does little to drive the plot, instead stumbling upon plot points seemingly by accident. Furthermore, Kouta never interacts with any of the series’ main villains for any length of time, and thus does not serve as a foil or a threat to them the way a typical hero would. Nana is a little more active and engaged with the plot, but the problem is that she accomplishes very little. She tries to protect her friends, but nearly always ends up having to be rescued. All in all, none of the obvious choices for “heroic” characters seem to fit the description.

Thus, the only characters who could fit the bill as “heroes” in Elfen Lied are Bandoh and Kurama. To fans familiar only with the anime, which portrays them as almost cartoonishly over-the-top in their villainy, the notion of either man being a hero may sound absurd. Many of Bandoh’s lines, in particular, are so outrageous that even a voice actor as talented as Jason Douglas struggles to make them sound natural. Nevertheless, the further the manga progresses the more apparent it becomes that the audience is meant to root for both him and Kurama.

The narrative attempts to invoke sympathy for Bandoh and Kurama by giving each one a young, innocent girl who attaches herself to him. In Kurama’s case, the girl in question is Nana; in Bandoh’s, she’s a middle-schooler named Mayu, who ran away from an abusive stepfather to live with Kouta and Yuka. Early on in the series Mayu rescues Bandoh when he’s bleeding on the beach after a fight with Lucy. The next time he runs into Mayu, he gives her his phone number and asks her to call him so he can kill anyone who gives her a hard time. He also reaches out to Nana after he finds out that she considers Lucy an enemy. For the most part, both Bandoh and Kurama treat Nana and Mayu horribly, as if they were nuisances or pawns. Nevertheless, the fact that they’re able to open up to another person at all is clearly meant to show that they aren’t as bad as they first seem.

In all likelihood, one reason why characters like the Unknown Man and Nousou exist is to make Bandoh and Kurama look better by comparison. If Bandoh is aggressive and enjoys killing people–including young people–then the Unknown Man must be an unapologetic murderer and a rapist to boot. He must also threaten Mayu so that Bandoh can look like a knight-in-shining-armor by saving her from him. If Kurama is a mad scientist who has been performing torturous experiments on children, then Nousou must perform even more painful and dehumanizing experiments. These characters are so egregiously, outrageously cruel that they deflect attention away from the inherent cruelty of Bandoh’s and Kurama’s plans, which would lead to the death of dozens or even hundreds of children.

A third character who seems to play a heroic role in the manga is Arakawa, a research assistant to the Kakuzawa family. She had hoped to become famous by taking part in their research, but eventually becomes disenchanted. She summarily gets to work developing a vaccine in order to eliminate the Diclonius once and for all. By any objective standard, Arakawa is a disreputable person who keeps disreputable company. For instance, she freely argues and makes bets with the Unknown Man even though she knows that he’s a sadistic serial rapist. She also chooses her research projects based only on what she thinks will help her attain fame and glory, no matter the moral implications. Still, the fact that she helps develop the vaccine seems to be all the evidence the series needs that the audience ought to care about her.

What all these characters have in common is that they actively work to eliminate the Diclonius. Kurama, who despite his flaws is the most humane of the three, acknowledges that he is not acting out of malice, but only to prevent further suffering and casualties. Bandoh, meanwhile, has the perfect excuse to kill someone and escape censure, as he admits openly at the start of the anime. Tellingly, the one time that Kouta, the audience’s stand-in, takes significant action is at the very end of the manga, when he shoots Lucy dead on her instruction. After her body starts to disintegrate, she admits that she hasn’t been able to live with the horrible things she has done for many years and asks only to be killed by the person she loves.

In a different horror anime, Jason Douglas’s character says, “We don’t think twice about putting a wounded animal out of its misery; why are people any different 59?” The reality is that this is far more than the self-justifying slogan of a nihilistic villain. As the history of abandoning or murdering disabled babies 60, the debate over capital punishment, and occasional modern cases of so-called “mercy killings 61” show, people are naturally predisposed to want to eliminate those who seem incapable of giving more than they take, who seem to be in intolerable pain, or who pose a threat to others. Rather than challenging this view, Elfen Lied encourages it by explicitly portraying those who hold it as justified and in the right.

In a world where the conventional therapies don’t work for everyone and are often hard on the patients, it can often seem as though there is no good way to manage severe mental illness. If the illness cannot be cured or managed, it’s easy to assume that the only way to eliminate the suffering it causes is to eliminate the sufferer altogether. In real life, rather that actively killing psychiatric patients, society simply lets them die much too young 62.

As such, families often find themselves caught in a pincer grip between an uncaring medical establishment on the one hand, and an activist community that openly dismisses their concerns on the other. At the furthest extreme, some people murder their own mentally-ill relatives. In the 1960’s, a father killed his autistic teenage son after catching the latter masturbating in public 63. So far, such incidents remain mercifully rare. However, they might become more common in the future, especially as traditional views about the sanctity of life seem to be receding in many parts of the world 64. If such a thing does happen, Elfen Lied‘s popularity and reach suggests that many people will be a lot more comfortable with it than one might suppose.

In summary, most of the horror in Elfen Lied stems from exaggerating the problems facing people with severe mental illnesses and neurological disabilities, and their families. The message of the manga, in particular, is clear: Diclonius have no place among ordinary humans and, if left to their own devices, will only kill and suffer. Therefore, they must be eliminated for both their own good and the good of society. If one sees Diclonius as a metaphor for the severely mentally-ill, then the implications become quite troubling indeed.

Works Cited

- “Eugenics.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2 July 2014. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/eugenics/ ↩

- “Overview of Huntington’s Disease.” Huntington’s Disease Society of America, https://hdsa.org/what-is-hd/overview-of-huntingtons-disease/ ↩

- “Tay-Sachs Disease (for Parents).” KidsHealth, October 2014, https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/tay-sachs.html ↩

- Centerwall, Siegried A. and William R. Centerwall. “The Discovery of Phenylketonuria.” Pediatrics, vol. 105, no. 1, 2000, pp. 89-103. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.105.1.89 ↩

- “Mental Health By the Numbers.” National Alliance on Mental Illness, September 2019, https://www.nami.org/mhstats ↩

- McKenzie, Kwame D. “How Does Untreated Psychosis Lead to Neurological Damage?” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 59, no. 10, 2014, pp. 511-512. PubMed Central, DOI: 10.1177/070674371405901002 ↩

- Power, Robert A. et. al. “Fecundity of Patients With Schizophrenia, Autism, Bipolar Disorder, Depression, Anorexia Nervosa or Substance Abuse vs Their Unaffected Siblings.” JAMA Psychiatry, vol. 70, no. 1, 2013, pp. 22-30. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.268 ↩

- Crump, Casey et al. “Comorbidities and Mortality in Persons with Schizophrenia: A Swedish National Cohort Study.” American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 170, no. 3, 2013, pp. 324-333. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050599 ↩

- Hirvikoski, Tatja et al. “Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder.” British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 208, no. 3, 2016, pp. 232-238. Cambridge University Press, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160192 ↩

- Donvan, John and Caren Zucker. “The Behaviorist.” In A Different Key: The Story of Autism. New York, NY, Broadway Books, 2016 ↩

- Bridgeford-Smith, Jan. “Witness to a Solitary Affliction.” Boulevard, Spring 2020, pp. 150-164 ↩

- Opar, Alisa. “Why children with ‘severe autism’ are overlooked by science.” Spectrum News, 18 October 2017. https://www.spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/why-children-severe-autism-overlooked-by-science/ ↩

- Feldman, Deborah. Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots. New York, NY, Simon and Schuster, 2012 ↩

- Volavka, Jan and Leslie Citrome. “Pathways to Aggression in Schizophrenia Affect Results of Treatment.” Schizophrenia Bulletin, vol. 37, no. 5, 2011, pp. 921-929. Oxford Academic, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbr041 ↩

- Donvan, John and Caren Zucker. “Screams, Slaps, and Love.” In A Different Key: The Story of Autism. New York, NY, Broadway Books, 2016 ↩

- Smith, Lori. “Why do I feel so flat, and what can I do about it?” Medical News Today, 11 September 2017 https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/319357 ↩

- Brown, Heidi. “To Escape My Autistic Son’s Violence I Ended Up Living in a Tent.” National Council on Severe Autism, 16 September 2019 https://www.ncsautism.org/blog//to-escape-my-autistic-sons-violence-i-ended-up-living-in-a-tent ↩

- Davis, Leigh Ann. “People with Intellectual Disabilities and Sexual Violence.” The Arc, 2011 https://thearc.org/wp-content/uploads/forchapters/Sexual%20Violence.pdf ↩

- Wenner Moyer, Melinda. “How pregnancy may shape a child’s autism.” Spectrum News, 5 December 2018. https://www.spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/pregnancy-may-shape-childs-autism/ ↩

- Warner, Richard. “Time Trends in Schizophrenia: Change in Obstetric Risk Factors with Industrialization.” Schizophrenia Bulletin, vol. 21, no. 3, 1995, pp. 483-500 https://www.mentalhealth.com/mag1/scz/sb-time.html ↩

- Rapaport, Lisa. “Assisted reproduction tied to risk of intellectual disabilities in kids.” Reuters, 15 November 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-assistedrepro-disability/assisted-reproduction-tied-to-risk-of-intellectual-disabilities-in-kids-idUSKCN1NK2WZ ↩

- Nasar, Sylvia. A Beautiful Mind. New York, NY, Simon and Schuster, 1998 ↩

- Deweerdt, Sarah. “The unexpected plus of parenting with autism.” Spectrum News, 16 May 2017 https://www.spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/unexpected-plus-parenting-autism/ ↩

- Simoila, Laura et al. “Schizophrenia and induced abortions: A national register-based follow-up study among Finnish women born between 1965-1980 with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.” Schizophrenia Research, vol. 192, pp. 142-147. ScienceDirect, DOI: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0920996417303134 ↩

- Donvan, John and Caren Zucker. “A Menace to Society.” In a Different Key: The Story of Autism. New York, NY, Broadway Books, 2016 ↩

- Donvan, John and Caren Zucker. “Doubly Loved And Protected.” In a Different Key: The Story of Autism. New York, NY, Broadway Books, 2016 ↩

- Leroy, Alexandre. “Why are people afraid of having an autistic child?” Quora, 11 December, 2017, https://www.quora.com/Why-are-people-afraid-of-having-an-autistic-child ↩

- Escher, Jill. “The data doesn’t lie: Autism is a massive national emergency.” National Counsel On Severe Autism, 27 June 2020. Retrieved from https://www.ncsautism.org/blog//the-data-doesnt-lie-autism-is-a-massive-national-emergency ↩

- Donvan, John and Caren Zucker. “The Vaccine Scare.” In A Different Key: The Story of Autism. New York, NY, Broadway Books, 2016 ↩

- Sinclair, Jim. “Don’t Mourn For Us.” Our Voice, vol. 1, no. 3, 1993. http://www.autreat.com/dont_mourn.html ↩

- Zeliadt, Nicholette. “Why autism remains hidden in Africa.” Spectrum News, 13 December, 2017. https://www.spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/autism-remains-hidden-africa/ ↩

- Donvan, John and Caren Zucker. “The Signature.” In A Different Key: The Story of Autism. New York, NY, Broadway Books, 2016 ↩

- Des Roches Rosa, Shannon. “Autism and Self-Injury: Talking With Dr. Rachel Moseley at INSAR 2019.” Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism, 3 October 2019. http://www.thinkingautismguide.com/2019/10/autism-and-self-injury-talking-with-dr.html?fbclid=IwAR33lzSWl5M-I8ncbKxWT9HPaGd8s8TXRXTqzP8uENuVy8HAx0abIpXrg5I ↩

- Bonnello, Chris. “A plea to the autism community, from one of your own.” Autistic Not Weird, 31 January 2016. https://autisticnotweird.com/plea/ ↩

- Wells, Philip. “Ex-psychiatric patient speaks of repeated abuse.” BBC News, 13 January 2014. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-25680659 ↩

- Shapiro, Joseph. “She Can’t Tell Us What’s Wrong.” NPR, 10 January, 2018 https://www.npr.org/2018/01/10/566608390/she-can-t-tell-us-what-s-wrong ↩

- Brindle, David. “Secret filming reveals abuse of disabled and autistic patients.” The Guardian, 22 May 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/may/22/secret-filming-whorlton-hall-bbc-panorama-abuse-of-disabled-and-autistic-patients ↩

- Shapiro, Joseph. “The Sexual Assault Epidemic No One Talks About.” NPR, 8 January 2018 https://www.npr.org/2018/01/08/570224090/the-sexual-assault-epidemic-no-one-talks-about ↩

- “Social model of disability.” Mental Health Foundation, 2020 https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/learning-disabilities/a-to-z/s/social-model-disability ↩

- Armstrong, Thomas. “The Myth of the Normal Brain: Embracing Neurodiversity.” AMA Journal of Ethics, vol. 17, no. 4, April 2015, pp. 348-352. DOI: 10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.4.msoc1-1504. ↩

- Whitley, Rob. “The Antipsychiatry Movement: Dead, Diminishing, or Developing?” Psychiatric Services, vol. 63, no. 10, October 2012, pp. 1039-1041. Psychiatry Online, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100484 ↩

- Gwynne, Miriam. “The journey thus far…” Faithmummy, 23 January 2013 https://faithmummy.wordpress.com/2013/01/23/the-journey-thus-far/ ↩

- Bonnello, Chris. “Bridging the Gap Between Autistic Adults and Autism Parents.” Autistic Not Weird, 26 February 2018. https://autisticnotweird.com/bridging-the-gap/ ↩

- Gwynne, Miriam. “What it is like to parent a child who can never be left alone.” Faithmummy, 19 March, 2017. https://faithmummy.wordpress.com/2017/03/19/what-it-is-like-to-parent-a-child-who-can-never-be-left-alone/ ↩

- Radical Neurodiversity. “Schizophrenia As Neurodiversity.” Intersectional Neurodiversity, 25 January 2017 https://intersectionalneurodiversity.wordpress.com/2017/01/25/schizophrenia-as-neurodiversity/ ↩

- Cohen, Alex et al. “Questioning an Axiom: Better Prognosis for Schizophrenia in the Developing World?” Schizophrenia Bulletin, vol. 34, no. 2, March 2008, pp. 229-244. PMC DOI: 10.1093/schbul/sbm105 ↩

- Lynch, C.L. “Invisible Abuse: ABA and the things only autistic people can see.” Neuroclastic, 28 March, 2019. https://neuroclastic.com/2019/03/28/invisible-abuse-aba-and-the-things-only-autistic-people-can-see/ ↩

- Hunter, Noel. “Defunding the Police: Replacing Guns With Prescription Pads Is Not the Answer.” Mad in America, 17 June 2020 https://www.madinamerica.com/2020/06/defunding-police-prescription-pads-not-answer/ ↩

- Auerbach, David. “Facilitated Communication Is a Cult That Won’t Die.” Slate, 12 November 2015. https://slate.com/technology/2015/11/facilitated-communication-pseudoscience-harms-people-with-disabilities.html ↩

- Sparrow, Maxfield. “If Not ABA, Then What?” Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism, 7 April 2017. http://www.thinkingautismguide.com/2017/04/if-not-aba-then-what.html ↩

- Beals, Katharine P. “And now, a mini lesson in hard-core neo-neurodiversity.” Catherine & Katharine, 29 January 2019 https://catherineandkatharine.wordpress.com/2019/01/29/and-now-a-mini-lesson-in-hard-core-neo-neurodiversity/ ↩

- The Neurotypical Wife. “The struggles as the spouse of a person with neurotypicality.” Facebook, April 22, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/theNTwife/ ↩

- Walker, Nick. “Guiding Principles for a Course on Autism.” Neurocosmopolitanism, 5 July 2016. https://neurocosmopolitanism.com/guiding-principles-for-a-course-on-autism/ ↩

- Beals, Katharine P. “Final installment on Neurodiversity and Facilitated Communication.” Catherine & Katharine, 10 February 2019. https://catherineandkatharine.wordpress.com/2019/02/10/final-installment-on-neurodiversity-and-facilitated-communication/ ↩

- Zeliadt, Nicholette. “Children with severe autism increasingly overlooked in research.” Spectrum News, 2 January 2019 https://www.spectrumnews.org/news/children-severe-autism-increasingly-overlooked-research/ ↩

- Ahmari, Sohrab. “Let’s make 2019 the year of mental health in New York City.” New York Post, 31 December 2018 https://nypost.com/2018/12/31/lets-make-2019-the-year-of-mental-health-in-new-york-city/ ↩

- Muench, John and Ann M. Hamer. “Adverse Effects of Antipsychotic Medications.” American Family Physician, vol. 81 no. 5, 1 March 2010, pp. 617-622 https://www.aafp.org/afp/2010/0301/p617.html ↩

- “My Son’s Autism and Disability: Unintended Consequences of a Polarised Debate.” Thinking Autism, 4 March 2020 https://www.thinkingautism.org.uk/autism-disability-consequences-of-polarised-debate/ ↩

- “Grateful Dead.” Deadman Wonderland, written by J. Michael Tatum and Patrick Seitz, directed by Joel McDonald, Funimation 2012 ↩

- Soy, Anne. “Infanticide in Kenya: ‘I was told to kill my disabled baby.'” BBC News, 27 September 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-45670750 ↩

- Maguire, Daniel C., “Death, Legal and Illegal – 74.02” The Atlantic Monthly, February 1974. https://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/politics/abortion/mag.htm ↩

- Glosswitch. “Schizophrenia is not a fatal illness, yet sufferers are still dying 20 years too soon.” New Statesman, 6 October 2014. Retrieved from https://www.newstatesman.com/health/2014/10/schizophrenia-not-fatal-illness-yet-sufferers-are-still-dying-20-years-too-soon ↩

- Donvan, John and Caren Zucker.” Home on a Monday Afternoon.” In A Different Key: The Story of Autism. New York, NY, Broadway Books, 2016 ↩

- Meyrat, Auguste. “How Assisted Suicide Quickly Evolves Into An Unfettered Right To Die.” The Federalist, 9 March 2020. https://thefederalist.com/2020/03/09/how-assisted-suicide-quickly-evolves-into-an-unfettered-right-to-die/ ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I absolutely loved the manga and anime and I really wish the anime had been able to do the full story. It’s weird to me that Nozomi didn’t make it in the anime, considering she’s basically the reason the show is called Elfen Lied. It’s literally the song Lucy sings at the end, that was taught to her by Nozomi. The ending had me crying though. I mean, Elfen Lied is my favorite anime and debatably, my favorite manga series. But yeah, that ending had me messed up.

I really enjoyed EL. Am 36 and have watched a lot of anime, and it’s one of my favorites.

Maybe it’s because they oversaturate the emotion, but for a change I actually pick up on it and feel for the characters.

Nice coverage of Elfen Lied. One of my go to anime and manga. It’s like having something sweet and spicy, contradictory but it makes you more aware of the flavors. It’s not perfect by any means but I liked how it mixed the sense of melancholy, fear, sadness with moe style. For me, I like experiments in breaking stylistic conventions and mixing archetypes. They may not always succeed or stand the test of time, but the effort interests me.

The show says some really interesting things about human understanding of evil; not to mention it does a damn good job of pulling at the heart strings (DAMN that music box).

My problem is that the ending seems to have tried to make yet another suggestion about this subject (nature of evil). Not only do they rush it terribly but its the least salient (most abstract) of the points they try to make, consequently leaving the audience both baffled and slightly unfulfilled.

I guess the moral point is that some problems (not evil as a whole) can be solved by humane treatment and connection (manga by the way screws that point massively, at least on Lucy’s part). And overall I think the story of anime is not as much moral as emotional, and those emotions are played well by the end to leave you yearning for unlikely happy ending for Lucy, delivering you in to her experience once again.

I liked the story of Nana and papa, Nana being used as a test subject exposed to extreme violence only stays sane because of her papa and is willing to do anything for her. Papa however has her own Dietrich daughter and is confronted with killing these dietrich and his love for his daughter.

The problem with the Diclonius children – – is that they are children with deadly weapons. Yes, they are shown – – to have the ability to be “human” (as adolescents / young adults), but it’s getting them to that stage of development that is problematic. Children are assumed to have diminished capacity for logical and moral decision-making, which, when coupled with unstable emotions and lethal abilities, means that they can (and do, in Elfen Lied) kill at the slightest provocation.

“No, you can’t have that toy.”

“No, you can’t go to so-and-so’s house.”

“No, it’s time for bed.”

Being able to say “no” to children is an essential part of parenting, but you don’t say “no” to a person with a gun on you. That’s the paradox of Elfen Lied. but how does one do that, while still protecting their caregivers and society at large?

I agree and I think that’s why the series comes across as so sympathetic to eugenic ideas. Occasionally I come across blogs and message boards featuring parents of children with terrible mental problems, and the genesis for this article was, in part, the tendency of some of these parents to allow their kids to do whatever they wanted, on the grounds that their children just couldn’t help being what they were and it was “too dangerous” to set boundaries. I feel like what “Elfen Lied” is really saying is that yes, it is indeed too dangerous to even attempt to set boundaries with such children–and so they should all be killed instead.

Well, the Institution seems to have done a decent job of figuring out how to socialize Nana, and while she wasn’t exempt from the inhumane treatment by any means, the introduction of a social figure absent of the inhumane impositions of the institution (Nana likely did not associate Kurama with the torments she received there, as she associated him with a loving parental figure) certainly seems to have gone a long way towards successfully socializing them into human society. Mariko required physical coercion to behave, but she had already given in to those impulses entirely due to emotional manipulation (“You’re not my Mamma…”), so we can consider her exempt from that model…Nana actually had someone that acted as a caring parental figure.

At the very least it would be a building block to building a foundation for a working system. Optimistically, one could say we discovered how to bypass “Kill All Humans” mode. It would definitely be an interesting concept to explore, psychologically speaking.

It’s true, the series hints that there might be a way of socializing the Diclonius, but the problem is it never does anything with it. It’s a huge missed opportunity, IMO. I actually think I would like the story a lot more if it focused entirely on how Nana was trained to overcome her bloodlust, and cut out most of the extra stuff about Lucy and Mariko and the rest.

I like how it deals with the eternal debate of nature vs. nurture in child rearing in an extreme scenario.

A real-life ‘split personality’ (correctly termed dissociative identity disorder, or DID) is nothing like what Elfen Lied depicts. The anime doesn’t “show” the dark side of a split personality, it creates the dark side for entertainment purposes.

The split personality isn’t in a human though. Lucy is an artificial killing machine essentially.

I consider the show to be a tragedy due to Kouta’s experience.

The sexual innuendo could have been left out entirely, but otherwise it’s a great story.

Which is better, anime or manga?

In my view, the anime’s better, because it has better art and less problematic stuff in it than the manga. That seems to be a minority opinion, however.

While the Manga goes further and is definitely more detailed and explicit, The anime somehow does a better job at hiding how random the storytelling really is. Both have advantages and disadvantages and overall I prefer the manga, but the anime somehow feels less lazily written, even though it ends where the manga is only half way through and has the exact same story otherwise.

When I first watched the anime, I had never seen anything quite like it and thought it was really good. As I’ve gotten older, my opinion has changed quite a bit. I now find a lot of the sexual content exploitative and the violence is graphic without really feeling like there’s merit to it. Looking back on it now it seems like a show about torturing “cute” girls for the sake of torturing them, rather than having anything interesting to say about the human condition or how we’d react to a new species like the diclonious showing up.

The science experiments seem a bit over-the-top. What is the point of firing a steel ball at their head? Even taking out the message of “scientists are evil m’kay” it’s still junk science. There are much more effective ways to measure the strength of one of their arms with much more accuracy than firing a steel ball. (have her push against a pressure plate)

I thought it tried way too hard. Elfen Lied shows absolutely no restraint in it’s story, and all of it seems to be under the guise of making something as dramatic and ‘sad’ as possible. Everything in Elfen Lied is dialed up to 11, and in a bad way.

Every single sad moment ends up just being a caricature instead of something actually moving. It gets to a point where the characters are so flat that their defining characteristics are how tragic their life was.

I have a huge amount of respect for shows that can show restraint. Stuff like Welcome to the NHK knows how to make a sad or emotional moment without feeling like it’s just trying to be cheap about it.

The cranking up to dial 11 really resonates.

It actually feels better if there are lower levels that build up rather than full on max all the time.

I think that this show was an attack on egalitarian values. To me it posed ethical questions and actually gave its own answers. I don’t think one could justify random murders, but it was difficult to feel bad for the kid who killed the dog in that one episode (you know what I’m talking about).

I’m not at all familiar with this show, though I enjoyed reading your analysis of it.

I also really like the final image included in the article titled ‘Lucy’. It’s beautiful!

I hated the ending (in the manga). The rest of the manga was mostly perfect and then, the ending comes in and ruins it. The sci-fi elements are bad and the actions scenes were never fun without emotional context. But even worse, there just seemed to be a bunch of added things that broke the world and the story into something incomprehensible.

Not to mention, the writing started to leave out too many details on both the reasoning of things and how things were unfolding.

I would recommend just watching something like Gunkoku no Brynhildr where the sci-fi is focused on and done right, which means that you can not be disappointed with the ending half as much as this one. Even though it is unrelated and you may not like it too much, it provides more closure for Elfen Lied because it actually explains and perfects the various things that went wrong in Elfen Lied’s ending (while following a different plot and world).

Rant over.

When I started collecting anime, Elfen Lied was one of the first titles I bought and I think it has some really strong points, but it certainly doesn’t escape me that the whole product is kind of juvenile in it’s late 90’s grimdark nonsense. Still, kind of like the The Devilman franchise, I can really appreciate it for its gore and the musical score saves a lot of the emotional moments that are otherwise on a wonky foundation. It definitely dabbles in some emotional manipulation of the viewer, but at the end of the day it gives you villains to hate and then proceeds to brutalize them, which is satisfying enough for me.

I found the anime enjoyable because it packs so many different themes into such a small number of episodes. That said, the ending was disappointing.

I couldn’t even watch the anime the first time I tried to watch it. I had just had a bad experience with psychedelics and this anime is a huge mind fuck. Just recently tried to rewatch it and it was amazing.

Down the memory lane here!

One of the first anime I watched, and boy, did I get a culture shock. I was expecting all the kawaii and moe stuff (which a little still happened) but it was easily dispersed within the first part of the show. The entire show gave me different aspects of what I thought of anime. I had been watching plenty before, but it had al pretty much fit the previous stereotypes I thought of. After finishing it, I really liked the show.

And probably the best part is with my older sister. I was always the “anime is taboo” type, even though I watched it very heavily. But then I talked with her, and she said that even she watched it (which i found weird, I’m 21, and she’s 23 and in the NAVY). She said that Elfen Lied was the first one she watched as well as one of her favorites. I honestly cant wait until she gets home to where we can discuss together since I have no one to do that with.

The excessive violence (not usually something I see from an anime) really struck a vivid impression in my mind (as well as the music in the op).

Really great read Debs. For me, I consider Elfen lied as a guilty pleasure. It’s not the greatest ever and is certainly not the worst. The only things that ruined it for me were the facts that the MC was kept an oblivious idiot, the strange pacing and the end. Excluding those things i enjoyed the show a lot. The character backstories and their interactions along side the mystery and suspense drove the show for me. However upon reading the manga i realized just how superior it is to the anime. Although the the manga did a bunch of twists and turns that made me go “DAFAQ?” i still prefer it over the anime because of the way it ended and how it handled the lore. The anime was just rushed and the ending was just too open. Even still the anime did it’s best and up until now it’s one of my favorite animes. For those of you who want the full elfen lied experience….go read the manga….like right now.

The anime kinda hints at the story being “deep” but that ending ruins everything.

But I recommend reading the manga, which this article is covering.

The manga adds more dimensions to the plot, to the gory stuff as well. The ending here is deep and fits well with the story. The characters are simple and pretty convenient, but at least aren’t irritating like Misa Amane or Sakura or dull like Lisa. I still can’t get over the fact that Kouta didn’t actually want to forgive Lucy, but he kinda did.

But then again if you think about it, he forgives Nyu not Lucy, gives her (them both) a chance (which I think Lucy definitely doesn’t deserve, but Nyu is a pure soul, and they both are the same person?!), also that Diclonius monster got what she deserved. This complicated mess here is well executed. Overall talking about the anime, imo, it wasn’t a great show, had many “issues”, but was thought provoking enough to get me to read the manga which I would recommend to anyone without a second thought. So if the anime got you even a little bit interested, you probably should be reading the manga.

I definitely agree with you about the anime adaptation. Elfen Lied is a complete utter atrociously written piece that deserves to be thrown in a fire pit and burned.

There was only one scene in the entire show that had any substance and then right after they ruined it because not only did you have to suffer about 11 episodes to get to it but Lucy and Kouta don’t even get seen back together at the end. Everything in this show feels like it was completely destroyed by all the putrid fanservice that gets in the way of storytelling especially the whole Nyu alter ego thing in Lucy and all the pathetic and laughable portrayals of human nature.

The dumbest moment in the whole show being when a dog getting killed just because of dumb kids making fun of Lucy’s odd look which also makes them gay characters in my opinion because no real men would treat a girl that way and that’s just scratching the surface of it.

The animation and art are also a complete joke as most of the CG that they use doesn’t even move right with the characters and sometimes not even being there in the show and I also gotta question why everyone’s eyes are so abnormally large to the point where they give me a seizure to look at.

Elfen Lied had some very large potential but it was so poorly written that it ruined it’s chances every possible way it could have.

Anyone else feel like there should be an anime remake of Elfen Lied or just me?

While it’s been my biggest anime-related wish that the series be remade to have a proper ending and be more true to the source material, I also dread the possibility: even anime adaptations that come from works that had little or no ecchi stuff tend to be ecchified – and from what I understand, the source material in this case had shittons of ecchi, especially in the parts that the anime didn’t get to show due to it still being a work in progress at the time. It’s not even goofy ecchi, it’s High School of the Dead ecchi, if not worse.

Great article, especially the discussion of eugenics as it relates to autism/neurodiversity. I have cerebral palsy and Asperger’s (the latter diagnosed recently), and this kind of thing boils my blood. I’m glad other people are recognizing and responding to it, or even recognizing that the eugenics message exists. In my experience, non-disabled people seem to think, “Nobody is loading you in a van and gassing you. Nobody has outright said they want to kill you. So calm down.” And I’m just like, ah, NO. There are so many things wrong with that mindset…welcome to my TED talk…

I liked the show at 18 but as an adult in my early 30’s the show’s flaws make it pretty hard for me to watch. Part of that is that I used to have depression but I got help 5 years ago and my tastes in media aren’t dark anymore. The music and opening art still moves me, but I don’t enjoy the show anymore due to the poor voice acting, weak dialogue, wandering plot, lack of character development, etc.

That is how I feel, I’m currently watching it, and the flaws are pretty noticeable. However, the story is moving.

Watched this entire show back to back in one night, a pretty decent romp/guilty pleasure and I actually enjoyed the story even though it clearly isn’t perfect.

Maybe I’m accustomed to utter shit tier anime like Genocyber because I thought this held up pretty well despite the flaws.

I watched it when I was more new to the anime community some years ago. I was maybe somewhere between 9 – 13 years old and watched it on youtube with german synchro (im german) and really liked it but also was a little traumatised for some time because of the dog scene and the part with his little sister. I haven’t rewatched it since then because it is to sad for me but I still know and lime the story. Maybe someday I will rewatch it but I’m 16 now and still have these scenes in my head (not in a traumatic way but I just remember movies and series I like for years) and don’t want to get sad, at least not for now. Thanks to anyone who took the time to read this.

Finally an actual serious analysis on my favorite manga. Thank you.

I thoroughly enjoy Elfen Lied. It’s basically a show about extremes. There’s no middle ground with the events of Elfen Lied or even with the character Lucy herself, which is fitting considering how people are generally one extreme or the other on opinions with EL. It’s cruel and yet sort of endearing.

It has a well crafted story that doesn’t get fleshed out like it should’ve been in the anime. I like Lucy and Nana’s characters but the rest of the cast is pretty weak.

A lot of people label it as 2edgy4me goreprn but it’s more than that. It has plenty of issues but every time I watch it I’m absolutely entertained and never feel like it’s too dumb.

I was around 13 when I first saw Elfen Lied. I remember how shocked and disturbed I was watching it. It was a hell of a journey. I’ve never seen anything so bloody and messed up.

I wouldn’t say it’s one of my favorite anime, but it left a huge impression on the innocent kid I was, it kinda burned itself into my memory. So even now, almost 10 years later, I still remember most of it even though I never rewatched it. Maybe I should.

In my opinion I felt kurama wasn’t a villain at all but a man who saw the error in his ways but was being held hostage in his occupation due to the promise he made.

Some of the character’s motives made no freaking sense. The glasses guy who was #35’s dad changed his mind too damn often, just to end up being blown up. Bye-bye.

A typical anime fan will, in my experience, watch Elfen Lied once thinking it is absolutely amazing and, after a year or two, look back on it thinking “I still enjoy this show, but god damn is this show mediocre”.

I really loved Elfen Lied and it wouldn’t be a stretch to say it is my favorite anime (didn’t like the manga as much). To say that the thing and attraction of the show is moe,nudity, violence and gore is quite wrong. All those things and everything else in the show doesn’t exist for it own sake but is part of art-piece that does everything to bring out the emotions of true childish innocence, the trauma of it being cruelly hurt and then kindness and empathy for it.

All tranquil, beautifully scenes and simplistic interactions and humor are there to take you back in to childish experience. Violence is so drastic also to match intensity childish experience.

I like the ambiguity in whether Lucy went back to live with Kouta and the gang as Nyu bc even though a lot of people think she didn’t deserve a happy ending, she would’ve finally got her family but she wouldn’t have hurt anyone innocent.

I just wanted to see Lucy live a happy life. That’s all I wanted. I wanted her to stop killing. I wanted people to stop tracking her down. I wanted people to stop treating her like crap. After all, it was the way people treated her that made her what she is. Can you imagine how traumatizing it is to see your school bullies beat your puppy (literally the only thing you love and care about in the world) to death, with a rock, right in front of you? After your literally only human “friend” told them about the puppy, knowing they would do something like that? I like to believe that if Lucy had been able to stay with Kouta, and the institute would have stopped chasing her, she wouldn’t have hurt a soul. I would bet my life on it.

I find its themes of isolation, abandonment, disappointment, innocence and the human nature of animosity towards different ones especially poignant. It could be because I feel a certain connection with the characters, but even though I watched it 2 years ago, I still sometimes analyse the problems it puts forth. This might stem from the fact that I rarely watch anime or consume others types of media (films, TV shows, books) just for entertainment or filling time.

If you liked Elfen Lied, watch/read Gokukoku no Brynhildr. They are both Lynn Okamoto’s works.

I didn’t find it creepy. I expected gore when I went in so wasn’t all that shocked although the amount of it and how graphic it was surprised me slightly, the dark themes were definitely present but I feel that it lacked the aspect of horror I love for in horror anime that anime like Another and Higurashi had. As good as it was I wouldn’t rate it that highly, nor would I recommend it to anyone.

I enjoyed this analysis looking forward to more content from you.

The idea behind Lucy’s development isn’t “Oh, Lucy is acting evil, but it’s understandable because she is angry at humanity”. It’s not just anger, it’s a completely fuked up and stunted development. And I mean development as in the word “developmental psychology”, not “plot development”. Since a very young age, she has basically been isolated in a research facility, and the experiments performed on her were more or less the only interaction she had with other humans.

That’s why her thinking is simply that of a small child. She doesn’t kill Kouta because she likes Kouta. Kouta’s parents are annoying and she doesn’t care about them, so she kills them. She doesn’t even make the connection that Kouta cares about his parents because her thinking doesn’t go far enough.

There’s an interesting experiment in child development where Person A hides a chocolate in one cupboard, then person B comes along, takes the chocolate and hides it in another cupboard. If you then ask the child where person A would look for the chocolate, they will point at the cupboard where Person B put it, because that’s where THE CHILD had last seen the chocolate. Children below the age of about 6 are literally unable to think about the situation from the perspective of someone else who isn’t in the room.

And that’s kind of what Lucy is. Her mental development was halted and she has the thinking of a small child, while being equipped with a powerful murderous weapon. Would you expect her to spontaneously discover enlightenment philosophy about the rights of all men just because a boy hugged her?

This show certainly defies the conventional outlook on morality.

Really wish there was an OVA or a season 2. Seems the series is dead sadly, it was flawed (a weak middle but hella strong beginning and closing acts) but a great watch. Ending just bummed me out as really the interesting relationship between Khouta and Lucy was just starting.

Made u think about humanity in general through all those acts. Like there were many scenarios about choices, sacrifice, and regret.

I think the split personality has a lot to do with the trauma they receive, just like in reality with MK ultra.