Fantasy Writing and The Middle Ages to The Renaissance

Fantastic Inspiration, Heroes and Morals: Drawing from the Middle Ages and Renaissance in your fantasy writing

Writers of all literature draw inspiration from many places. Whether it is from research or real-life experience, we are all informed by the stories we hear and live. Fantasy writers stand on the backs of giants even if we don’t know it. Fantasy literature has a rich and long history that spans from the very beginning (and beyond) of recorded language. Even if unaware, fantasy writers are influenced by the very zeitgeist of this heritage. Whether it be through exposure to original myths and fairy tales, or simply from the osmosis from reading other writers, fantasy is drenched in its very history. This discussion is going to focus on the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods and the patterns and trends in how they developed from the Classical Antiquity period – patterns and trends that are still very present in fantasy writing today. Please note this is a synoptic review and cannot address all literature or influences from this period. Feel free to share research and literature from these periods that this short article did not get to.

The Middle Ages is a historical period from roughly between the 5th to the late 15th centuries. It, to an extent, is often considered as the Post-Classical period. This was a period characterised by mass migrations, decentralisation, and the rise of Christian religions. From a literary perspective it was an unusual mix of heroic and moral tales.

The Renaissance is the transition between the Middle Ages and the modern period and is usually focused on within the 15th and 16th centuries but can be considered to span from the 14th to the 17th century. The Renaissance is often viewed as a time of breaking away from the past, but largely it was a period for new thinking, while at the same time a nostalgia for the Classical Antiquity period. In literature it was a time of expanding original mythologies and the retelling of historical stories. It is often best characterised as the time of William Shakespeare.

For a fantasy writer these two periods began to explore the concepts of morality within the fantastical. Much of the fantastical literature Classical Antiquity period was centred on the interactions of the gods. This meant that the stories were often representing particular “religious” positions of the various gods, but not always morally driven. The Middle Ages’ literature is often more strongly linked to the teaching of morality and life lessons. The stories, although designed to entertain, had a purpose in sharing the information about the consequences of choices, even (or especially) for heroes.

The Middle Ages

This period of the Middle Ages offers two areas of interest that have become longstanding tropes in fantasy novels and in themselves have been continuously reimagined across a range of genres: the rise in popularity of the Arthurian legends, ‘an obscure war-leader called Arthur and his supposed mentor, the Welsh wizard Merlin’ 1, and the animal fables.

The Legend of King Arthur

The legends of King Arthur and his wizard advisor Merlin have been first credited to Geoffrey of Monmouth in his pseudo-historical Historia Regum Britanniae (c 1130s), a work that did much for the Arthur legend. As Maureen Duffy suggested ‘Geoffrey Monmouth made Arthur respectable by giving him a Latin prose history. What Geoffrey did was to catch the already popular Arthurian legend and canalise it’ (49). While much of the story of the quest for the grail can be traced to French poet Chretien de Troyes, whose poems Perceval, or Le Conte del Graal (‘Perceval, the Story of the Grail’ c 1135-1190) were completed by other writers, is responsible for introducing the motifs of the quest for the Grail as a symbol of Christian perfection and the cuckolding of Arthur. Stephen Knight in his examination of the Arthurian legends stated that within ‘early Welsh tradition the versions of Arthur range from an ideal soldier to a supernatural super-hero’ (8).

When designing a protagonist, especially a hero, in fantasy writing there are a number of considerations that need to be made. The interesting element of the range in the Arthurian tales is the manner in which one character can be reshaped to fit the narrative’s purpose. Writers need to consider when designing their protagonist how the values, actions and motivations of the character will fit within the focuses purpose of the story. Revisiting Arthurian tales is a good action to see how a similar character’s representation impacts the overall narrative direction and reader message. We see this also present in many modern fantasy, but seldom to this degree where the key protagonist is framed as the same person, but told in different ways.

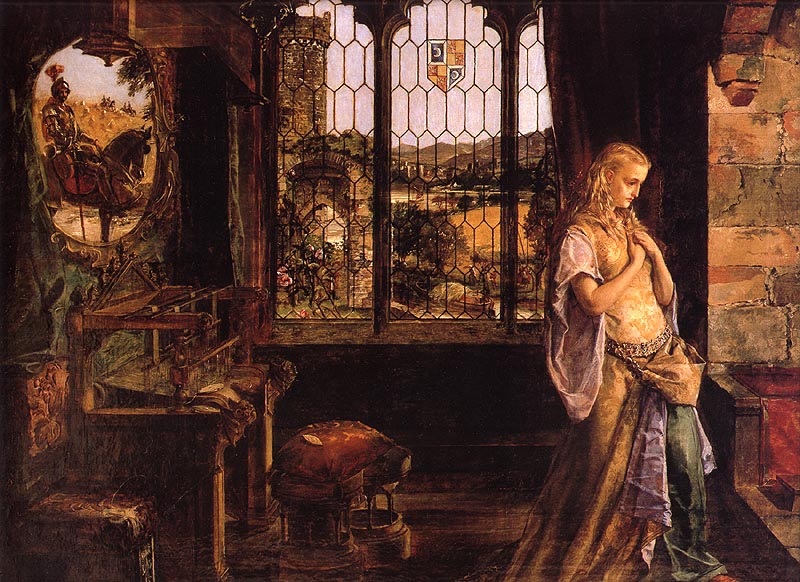

Though the Arthurian tales suffered a decline, the romances became popularised again in the latter half of the 20th century. T.H. White’s The Once and Future King (1958) chronicles the raising, romance and ruling of Arthur, largely based on Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (1485), and Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon (1982) is a retelling of the tales from the perspective of the female characters, are only two of the many interfaces developed based on the myth of Arthur, Guinevere and the Round Table. A topic that has long captured the imagination. 2 The Arthurian legends are the forerunners for the Chivalric Romances, a form that influenced the development of the Romance genre, a mode that continues to bleed over into most genres.

However, a fascinating aspect of these early Arthurian legends were their fantastic elements, Dennis Kratz indicated that the ‘world of Arthurian romance derives much of its strangeness from its Celtic origins, a mythology based on the belief in an Other World that humans can enter, whose inhabitants they can challenge and where they can enjoy the love of fairy women.’ 3 The Celtic mythology that was immersed into the later more Christian written Arthurian legends was not unusual for this time as Lucie Armitt pointed out ‘We know that a different relationship existed between literary representation, reality, and fantasy during the medieval period, largely due to the extensive faith held in the supernatural (both divine and demonic) at the time.’ 4 The faith in a present omnipotent god instead of reducing the production of fantastic tales instead saw the change in form of folk-lore and mythology as it became adopted into Christian stories.

One such form of literature was the Saints’ Lives tales that have been well preserved, because Saints’ Lives were considered better constructed. This was in part because the genre had a longer history, going back in Latin to such models as the Life of St Martin by Sulpicius Severus (fourth century), and partly because the life of many saints has a natural climax in the passio or martyrdom. Such Lives are very common in Middle English, both in prose and verse. This adoption of other cultures and times myths and stories is not unusual, even the ancient tales of Homer would have been adaptions on early mythologies. As Maureen Duffy argued, ‘We remake our mythology in every age out of our own needs. We may use ideas lying around loose from a previous system or systems as part of the fabric. The human situation doesn’t radically alter and therefore certain myths will be constantly reappearing.’ 5

This is an interesting concept for contemporary fantasy writers. The adoption of old myths in their own novel’s own world acts to adapt and change those traditional views into modern understandings. At the core, the search for the grail relate to common ideas of a search for a source of immortality and the desire for a sacrifice to be a martyrdom. Both of these are incredibly common tropes in contemporary fantasy literature. The idea of martyrdom is often interpreted as the protagonist who would sacrifice themselves rather than abandon their beliefs. These are ancient ideas being recycled in modern fantasy, yet still readers are fascinated and drawn to these concepts.

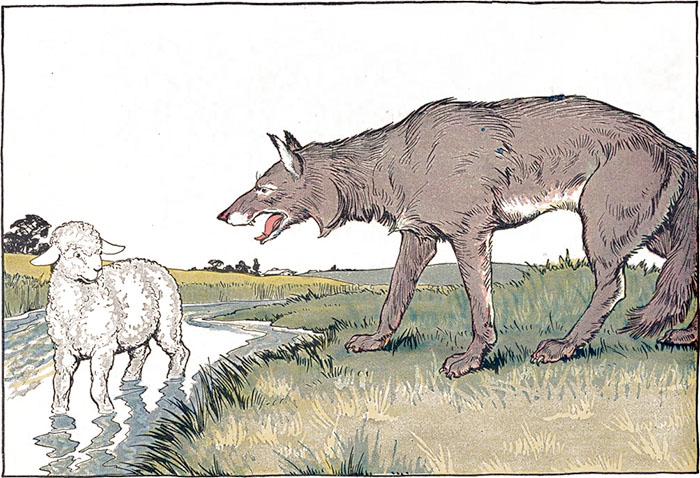

The Animal Fable and Aesop

The animal or beast fable is used in a number of different forms and owes its heritage to a much older time, as the transformative, intelligent, talking animal was present in many ancient myths. Today’s well known Aesop’s Fables did not create the concept. Ogilvie identified that ‘A man named Aesop may once have existed, perhaps a Greek slave in Samos in the sixth century: but Aesopic fables, that is short morality tales whose main actors are animals, go back beyond history. They were certainly used by early Greek poets such as Archilochus and Pindar’ (188). While animal, or beast fables, are often linked to the moral writings of Aesop the motif and allegorical use of intelligent, 6 and often talking animals, is a common trope in modern and ancient tales. One of the best loved of course is Aslan from Narnia, ‘His voice was deep and rich and somehow took the fidgets out of them. They now felt glad and quiet and it didn’t seem awkward to them to stand and say nothing.’ 7

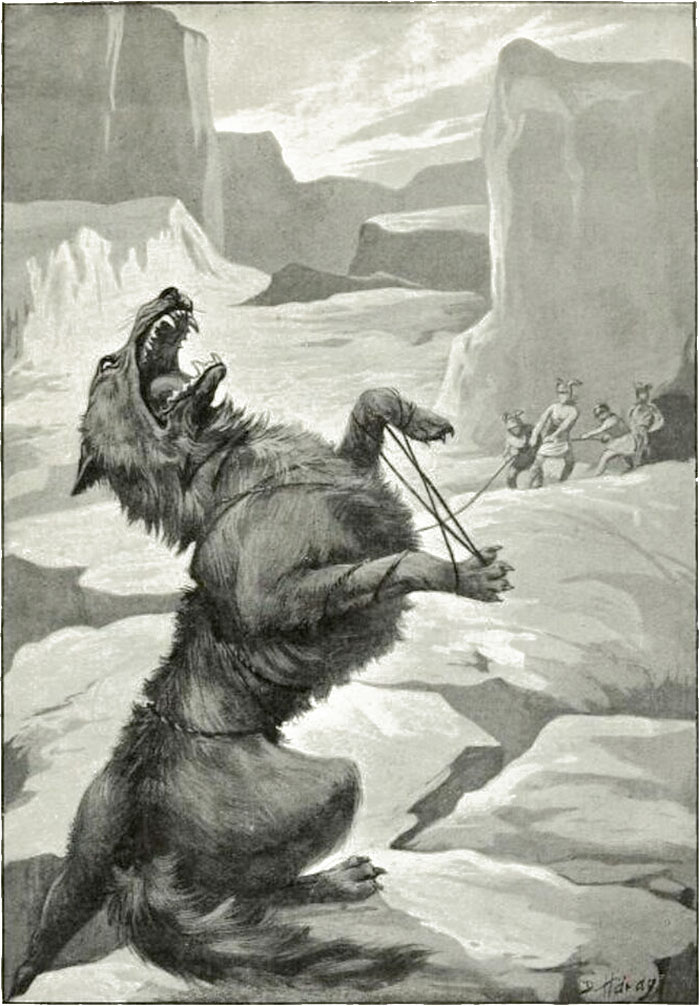

The use of the intelligent or allegorical animal has been used in several different ways: in Greek literature Hesiod used the beast fable to ‘illustrate the miseries of his world, in which justice is often defeated, Hesiod makes use of the story of a nightingale whose pleading cries are useless in the talons of a hawk’ 8. In Medieval literature it ‘was the tale of the transformations of a human being into an animal, particularly a wolf. The Christian Middle Ages produced the finest literary treatments of the werewolf theme.’ 9

The speaking animal is also a common trope, used to guide or impart wisdom. All ideas that are common across many literatures, including fairy story collections, classical Greek where it’s moralised as Aesop, Eastern tales, Apuleius’s Golden Ass, the Old Testament, Ancient Egyptian, easily stretching the idea back five or six thousand years. In contemporary fantasy the animal tale is still an important component and often occurs in two main forms: the transformation of human to animal and the intelligent animal helper.

The fascination with transformation, particularly the idea of were-creatures is often present in some form in most urban fantasy stories. Often both in a positive and negative manner. It deals with the issue of balancing the animal and human sides that all people are perceived to have, but often in quite a literal manner. Also the animal helper tends to be in the form of a witch’s familiar or at times a human who has been cursed into animal form. Either way their role is to provide guidance for the protagonist. However, the allegorical role of the animal fable is less used, but instead there are strong connections created from the motifs assigned to particular creatures that are used in both myths and fables. For example, ravens are presented as associated with intelligence and cunning, while rats are conniving and brutal, and spiders are meticulous and proud. All such motifs are traceable to ancient myths or taken from the roles of animals in the Aesopic fables.

The focus on the morality purposes of animal fables has perhaps waned, but this is instead now interpreted through the particular presentations of animal types or associate animal links. This can be easily demonstrated through the Harry Potter houses were both vices and virtues have been associated with their animal representations. However, there is still a strong association with these concepts of morality that remain in much of modern day fantasy. Much of this has come about from the later development and use of fairy stories, but it has its roots in this period. The hero must make sacrifices and honour should come first. Morality and choice matter, and all actions (or inactions) have consequences. There is much from this period that is interesting inspiration for a fantasy writer to draw from.

The Renaissance and Early Modern Period

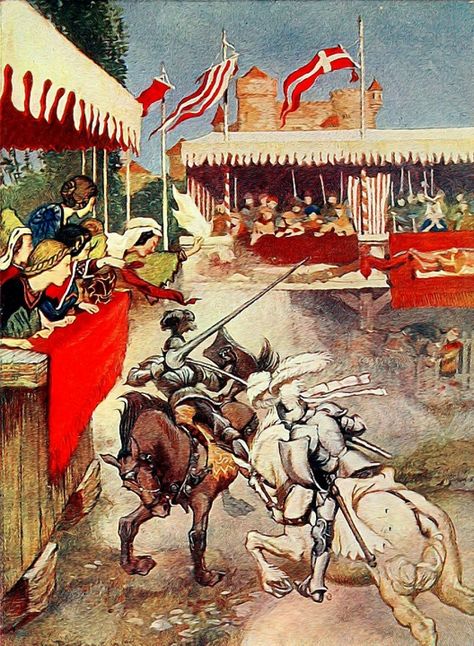

The 15th and 16th century saw a significant flowering of lengthy tales of fantasy in prose form, and of the Chivalric romance. 10 This is often attributed as one of the direct ancestors of the modern fantasy novel, and indeed the new subgenre of paranormal romance has much in common. Adventure tales of knights and heroes who participate in quests and drew on themes of romance. Charlotte Spivack in her work titled Merlin’s Daughters argued that the ‘medieval romance, the ancestor of fantasy, combined the mundane and the magical, the picaresque and the numinous, the physical and the supernatural,’ 11 wherein lay its appeal.

The Chivalric Romances

The Chivalric romances owe their content largely to a further romanticism of the Arthurian legends. For as Duffy pointed out, ‘The most common figure in the enchanted landscape is of course the knight himself: the young hero proving himself by his adventures as he pursues the chivalrous ideal in order to be worthy of the lady who has sent him forth.’ 12 The English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, of unknown authorship, is considered the ‘apex of Arthurian enchantment’ (57) as it ‘combines three fairy traditions, the Celtic, the romance and the folk, and does so effortlessly’ (57). The story of the Green Knight has a number of aspects: as the Green Man symbolising fertility and rebirth; as a Christ figure; or equally as ‘the story of the ego in pursuit of its ego ideal, told through the imagery of symbol and magic’ (55). It is a story rebounding in allegory and idealism.

The poem also draws on traditions of the epics, choosing to refer to these as the contextual history for the Arthurian tale. ‘It was Aeneas the noble and his high kin/ who then subdued the provinces’ (transl. Kline I 5-6), referring to the Romans that settled in Britain and the even older history of King Arthur, ‘But of all that here built, of Britain the kings,/ ever was Arthur highest’ (II 6-7). Interestingly the Chivalric romances and this period of literature was an important component of the later Gothic romances also. As Michael Moorcock in Wizardry and Wild Romance identified, ‘The Gothic Romance, which grew to popularity during the Romantic Revival had much of its origins in the Chivalric Romance, but emphasised the element of terror and attempted, usually, to rationalise the supernatural element.’ 13 Much contemporary fantasy does, as part of its hero’s journey, include codes of honour and ideas of gallantry. As well as often in the early storytelling an inclusion of innocent love and bravado that is later betrayed and turned to reflect the more cynical attitudes of the modern times.

The Fairy Queen

A return to the poetic idealisation of fairy can be seen in Edward Spenser’s The Fairy Queen (1590-96). A poem that draws strongly on the epic tradition, it is clearly ‘modelled on the Italian romance epics of Ariosto and Tasso, it is by Malory out of Ovid, the work of a man so saturated in the symbols and myths of the Italian Renaissance that it seems incredible that he had never been to Italy.’ 14 The Fairy Queen shares many characteristics with the Chivalric romances, but has a stronger fairy-tale focus with the inclusion of dwarfs, magicians, dragons, nymphs and so forth.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

As a similar age and theme as William Shakespeare’s own fantastical works, it continues the tradition of renewing myths and legends. Later works in the Renaissance saw a tendency to rework legends and fairy tales and offered a revival of topics picked up by poets and playwrights. For example, this includes Robert Greene’s Pandosto (1588), which was the inspiration for Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, and Thomas Lodge’s Rosalynde the source of As You Like It. A number of Shakespeare plays also deal with elements of the fantastic, the best known would be A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1595). It is a comedic tale of four lovers lost in an enchanted wood whose lives are meddled with by the fairies. It is clear in Shakespeare’s work that a fascination with the supernatural was still of interest to his audience. As Katz pointed out, ‘Shakespeare’s prominent use of fantastic elements has particular importance for the history of English Literature, for the revival of fantasy by English Romantics in the nineteenth century owes much to their view of Shakespeare as a fantasist.’ 15 Shakespeare’s works are perhaps some of the most influential in developing the fantasy tropes that are still used today. Although clearly he was reimagining old tales with folk-lore and fairy-tale elements, Shakespeare was able to create a plethora of accessible supernatural characters and situations that are still relevant. The meddling fairies of A Midsummer Night’s Dream are reflecting the vain, fickle and dangerous fairy of Celtic folk-lore.

War for the Oaks by Emma Bull especially appears to draw on Shakespeare’s work for inspiration. Elements of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and in particular Puck, are reimagined by Bull for her tale. Bull’s character of the Pouka, name and type of creature, is a clear nod to Shakespeare’s Puck. Where a fairy names and describes Puck, ‘Either I mistake your shape and making quite,/ Or else you are that shrewd and knavish sprite/ Call’d Robin Goodfellow: are not you he/ That frights the maidens of the villager;’ (II i 32-5), Bull has used the name ‘Robin Goode’ (73) and creates a character full of mischief. Both characters are able to transform and delight in leading humans astray: ‘I’ll lead you a round,/ Through bog, through bush, through brake, through brier,/ Sometime a horse I’ll be, sometime a hound’ (Shakespeare III i 94-6) and ‘“It’s the way I’m made, I suppose. For centuries, my kind have delighted in luring travellers off the path and into the marsh for the sheer pleasure of seeing them wet their feet’ (Bull 50). The pettiness, arrogance and interfering natures are also captured in both texts.

Shakespeare has the king and queen of fairy in dispute over a servant boy, ‘Oberon: Ill met by moonlight, proud Titania. Titania: What, jealous Oberon.’ (II i 60-1). While Pouka and the Glastig bicker, ‘“Fool of a pouka! Are you ass, as well as dog and man?”’ (Bull 29) and ‘“I would raise my leg to you, were you worth the effort.”’ (30). Both stories focus on the interference of the fairies with humans in an arrogant and presumptive manner. In War for the Oaks the Glastig says to Eddi, ‘“We will treat you very well, but you must not plague us with questions. Our concerns are greater than yours, and beyond your ken.”’ (30), while Oberon takes it upon himself to change the feelings of the young lovers, ‘Take thou some of it, and seek through this grove:/ A sweet Athenian lady is in love/ With a disdainful youth; anoint his eyes:’ (Shakespeare II i 259-61). Both Oberon and the fairy lord William Silver play at love, with Oberon tricking Titania, ‘What thou seest when thou dost wake,/ Do it for thy love take,/ Love and languish for his sake;’ (II ii 27-9), and William having cast a glamour over Eddi, ‘He’d toyed with reality, bent her perceptions, and showed not the least guilt at the admission’ (Bull 175). Finally, it should be noted that Bull has the fairies invite Eddi to their Midsummer Eve celebration of music and magic, ‘Around her, fantasies and illusions circled and stamped and spun, in glimpses of flying hair around uncanny faces, extravagant motion of inhuman arms and legs’ (243), it is easy to see that Bull was influenced by Shakespeare’s own interpretations of the fairy-tale and folk-lore of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Fairies are not Shakespeare’s only supernatural creature. Due to Renaissance England’s fascination and, to an extent, belief in otherworldly influences, this was a period when ‘Apparition, especially ghosts urging vengeance, are stock dramatic devices of both Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre.’ 16 Hauntings, both spectral and psychological are key components of a number of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies and histories; a strong forerunner to the ideas popularised in Gothic literature and contemporary fantasy. Hamlet and Macbeth both utilise apparitions that affect the characters and stories in an irreplaceable manner. Both tales have historical sources, yet Shakespeare attributed their dramatic actions to a supernatural influence. Macbeth especially uses strong supernatural themes in the use of the witches, ghosts and weather to highlight to the Jacobean audience the dangers of meddling outside the natural order. For when Macbeth murders the rightful king the natural order is upset, ‘by the clock, ‘tis day,/ And yet dark night strangles the travelling lamp:/ Is’t night’s predominance, or the day’s shame,/ That darkness does the face of earth entomb,/ When living light should kiss it?’ (Shakespeare II iv 7-11).

Advert for Libby McNeill and Libby’s Meats!

The concept of the supernatural disturbing nature is an ancient one and reflects our human desire to attribute natural, but seemingly unknowable, phenomena with external, often supernatural, influences. Many fantasy novels utilise a similar system to create an atmospheric undertone and to signpost “happenings” occurring in the novel. For example, Bull includes particular weather references that reflect the supernatural situation of their novels. In War for the Oaks the weather reflects the wild magic of the faerie, ‘It had none of the rough-sided cold of winter in it; it was damp, with a spoor of wildness that seemed to race through Eddi’s blood. It made her want to run, yell, do any foolish thing…’ (23). While in Mercedes Lackey’s novel Burning Water the Incan god’s influence changes the weather, ‘the air smelled more like a tropical rainforest than dry-as-dust Texas’ (223). The treatment by Shakespeare of fantastic elements he adopted from older traditions continues to influence many modern fantasists, for as Kratz clearly stated, ‘Neither the importance of the fantastic in Shakespearean drama nor the importance of Shakespeare in the history of fantasy should be underestimated.’ 17

Where the period of Classical Antiquity is often a source for mythologies and monsters for fantasy writers, the Middle Ages and Renaissance are exemplars of borrowing narratives. What these periods help demonstrate is the way in which older stories can be told within the contemporary context and still be powerful and evocative. Shakespeare will always remain an excellent example of this. Little of his works are purely “original” in the source – he takes from myth and history but tells the story in his own way. At times it can be difficult as a fantasy writer to feel that one’s voice is new and that the stories being told are not derivative. All literature, regardless of genre, is derivative. We are all living experiences others have lived and telling stories that have already been told. This does not diminish their value. Instead, it means that you are participating in a truly human experience.

It means you are a storyteller.

Works Cited

- Pringle, David Ed. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Carlton Books Ltd., 1998. P. 11 ↩

- Jakubowki, M. Modern Fantasy for Adults 1957-88. In N. Barron (Ed.) Fantasy Literature: A reader’s Guide. 1990 ↩

- Kratz, D. Development of the fantastic tradition through 1811. In N. Barron (Ed.) Fantasy Literature: A reader’s Guide. 1990. P. 19 ↩

- Armitt, L. Fantasy Fiction and Introduction. The Continuum. 2005. P. 19-20 ↩

- Duffy, M. The Erotic World of Faery. Hodder & Stoughton. 1972. P. 31-2 ↩

- Pringle, David Ed. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Carlton Books Ltd., 1998. P. 20 ↩

- Lewis, C.S. Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories. London: Geoffery Bles Ltd., 1966. P. 117 ↩

- Duffy, M. The Erotic World of Faery. Hodder & Stoughton. 1972. P. 5 ↩

- Duffy, M. The Erotic World of Faery. Hodder & Stoughton. 1972. P. 13 ↩

- Pringle, David Ed. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Carlton Books Ltd., 1998. P. 11 ↩

- Spivack, C. Merlin’s Daughters: Contemporary women writers of fantasy. Greenwood Press. 1987. P. 5 ↩

- Duffy, M. The Erotic World of Faery. Hodder & Stoughton. 1972. P. 55 ↩

- Moorcock, M. Wizardry and Wild Romance: A study of epic fantasy. London: Victor Gollancz Limited, 1988. P. 29 ↩

- Duffy, M. The Erotic World of Faery. Hodder & Stoughton. 1972. P. 127 ↩

- Kratz, D. Development of the fantastic tradition through 1811. In N. Barron (Ed.) Fantasy Literature: A reader’s Guide. 1990. P. 27 ↩

- Kratz, D. Development of the fantastic tradition through 1811. In N. Barron (Ed.) Fantasy Literature: A reader’s Guide. 1990. P. 26 ↩

- Kratz, D. Development of the fantastic tradition through 1811. In N. Barron (Ed.) Fantasy Literature: A reader’s Guide. 1990. P. 27 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I LOVE THIS ARTICLE!! Filed my love for great writing and the Renaissance !!

Great topic, and I enjoyed reading it. Particular kudos for your mention of Aslan tying into Aesop’s fables, since I had never heard of that connection before.

I’d rather have medieval tales based in alternate realities, while I’m interested in history, with fantasy you get more surprises.

What are some good titles ABOUT the middle ages?

When does middle age officially end? The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry would be one of my choices but the character is technically retired rather than in his fifties… Devastating, sweet little book about rediscovering purpose.

A lot of later Iris Murdoch novels are good on the trials of middle age, albeit a very specific upper middle class fantastical, almost mystical version of middle age.

Diary of a Nobody.

Anything and everything by Barbara Pym.

De Beauvoir’s volumes of memoirs make excellent reading: full of fascinating detail about the times in which she lived and people she knew, and of wisdom and insight. Hers seems a life fully lived.

Why is medieval fantasy so popular? I’ve always wondered why such a niche version of fantasy has become so iconic and loved, like how come medieval is more popular then Rome or Greek fantasy?

Because of the influence of Gothic literature, Romantic poetry, and Victorian art that depicted Medieval scenes (like Pre-Raphaelite art), art forms that influenced modern fantasy, the Medieval era has a special place in the modern Anglo-American imagination.

What we call “Medieval” in fantasy comes to us from Gothic, Romantic (late 18th/early 19th century), and Victorian (mid/late 19th century) ideas about the time; it bears only a passing resemblance to the actual Medieval era in European history.

In Gothic literature, contemporary beliefs about the Middle Ages provided a contrast to the developing ideology of the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution: a world of monarchy and religion, ruled by superstition, magic, violence as opposed to the ordered, rational, scientific world presented by the Enlightenment.

In both Romantic and Victorian art, Medieval tropes were deployed as nostalgia for a simpler time, for nature unspoiled by industry, for a time of Christian virtue and chivalry, but also as a way of understanding how the ghosts of the social hierarchies of the past still linger in the seemingly liberating world of democracy and capitalism.

Even as the Industrial Revolution replaced kings with Parliaments and the Church with a scientific understanding of the universe, old forms of living and old ideas still lingered. These are the ghosts and ruined castles and haunted suits of armor of Gothic literature.

As Europe moved from the Industrial Revolution of the 18th-19th centuries into the 20th century, we see a bunch of new discoveries upending centuries-old beliefs: Nietzsche says that morality is a human construct, Freud says that there are all kinds of invisible forces in our minds beyond our control, Einstein says that even time itself is relative. These ideas influenced the art of the 20th century, whether in stream of consciousness narratives with unreliable narrators or art that depicted impossible angles and perspectives (i.e. cubism) or didn’t depict anything at all (abstract art).

A lot of early fantasy, whether written by Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, or Tolkien, were reactions against the destabilizing and disorienting effects of modernism (arguable, yes; I’m perhaps oversimplifying here). This is why fantasy was seen for so long as a conservative art form, in contrast to the more progressive science fiction of the 60s and 70s.

Fantasy writers were taking Victorian and Romantic (mis)conceptions of the Medieval Era and using them to tell stories that could not be told in the modern world: stories of good and evil, of individual heroes wielding great power and exercising their free will independent of the constraining forces of modern society.

But as with Gothic literature, fantasy literature isn’t just a vehicle for backwards-looking escapist tales. The backdrop of the Medieval era is also deployed as a critique of modern industrial capitalism, of fascism, of the power of the modern state.

Sorry if this was disorganized and rambling and maybe a little imprecise!

I’m not an expert on Medieval history at all but I do have all of this knowledge about Romantic and Victorian literature clogging up my brain tubes with no outlet since I left academia.

Speaking for myself, it’s because I don’t like guns in my books. I don’t mind them in other media like movies/ tv, but I don’t want wide-spread use of firearms to exist in my books because I find that boring.

It many of writers minds’ eye, medieval is the last era that maps still had large sections marked “here there be dragons” on them. The technology is advanced enough that the writer can comfortably equip the adventurers with what ever gear is needed without worrying too much if said gear would be an anachronism. There are unoccupied, largely unexplored areas for major threats to arrive that a small band of heroes can deal with without the reader wondering why the army isn’t being sent it.

The lasting legacy of Arthurian stories, Robin Hood and Ivanhoe.

Here’s a fun fact for you: Ivanhoe was verrry popular in the American South in the years before the Civil War. Because white Southerners were real into thinking about their screwed up patriarchal society where foreigners recounted horrifying accounts of sexual, emotional and physical abuse of the enslaved, as a chivalrous one.

There is overlap between those. Medieval is mostly a time and technology age just referring to the middle ages while Greek and Roman is a cultural theming. Since secondary world’s are not copy and pasted, you can have plenty of overlap between the two.

As for why, because a ton of stories just don’t work with technology in them. How many plots would be rendered completely pointless in a world with telephones and Fed-Ex? Where you could call up someone local, have them ship the mighty item over and call it a day? Or instead of the naive kid walking into an empty ruin where his determination and magic can save him, instead had to break into a modern fort Knox? With modern education in security, alarms and instant kill weapons?

Medieval stories are functional, urban technology just makes too many of the fun and interesting stories completely pointless.

As a child my first experiences of books had illustrations of knights and dragons, swordsman and jesters… I spent my holidays running around ruined castles. Medieval fantasy is a ways of reliving some of that but as an adult…

A lot of “Medieval” fantasy is drawing influence from anytime from around the Dark Ages through the early stages of the Industrial Revolution. So not really a specific time period at all.

I’ve always enjoyed the tales of Arthur, but Le Morte D’Arthur is just too much for me. It’s so grim. From the moment of Uther Pendragon’s birth, if not earlier, Arthur’s bloody fate is sealed.

T.H. White is such a person. If you want a literary step up from the popcorn fantasy out there!

I don’t imagine I could have been introduced to the story of King Arthur any better way.

I love Lancelot and Arthur’s simplicity in wanting to be good.

Pretty much every sitcom in existence owes a nod to A Midsummer Night’s Dream for introducing the trope of having a simple misunderstanding set off a cascading cavalcade of hilarious events.

It’s funnier than I expected.

It’s hilarious and nonsensical and sassy.

The Fairy Queen is so renaissance tropey that I can’t even list all the ways.

Very true. I feel like I have every right to despise this book. It stole three years of my reading life (off and on). But for some reason, I don’t hate it. It aggravated me, but it also engaged me, in a weird sort of mishmash.

I was expecting to enjoy this poem, but I wasn’t expecting to enjoy it quite as much as I did.

A masterpiece of medieval symbolism and epic poetry craziness.

Definitely Thomas Berger’s Arthur Rex.

The Middle Ages really do seem to have attracted people. My recommendations:

Peter Vansittart: he wrote several mediaeval-set novels, incuding Lancelot and Parsifal, which take revisionist views of the Arthurian cycle and its characters, and The Tournament, The Death of Robin Hood and Three Six Seven: Memoirs of a Very Important Man, which could be described as Mr Pooter as the Romans leave Britain.

Julian Rathbone: The Last English King, and Kings of Albion

Hamlet – rather closer to Saxo Grammaticus’s version – appears in company with Beowulf and King Arthur in Henry Treece’s The Green Man

Your clear writing and synthesis inspire me to think further about this topic. Like, how does science fiction borrow from these traditions? Thank you for your essay.

I liked Unsworth’s Morality Play, 1380 is at the cusp of ‘medieval’ and ‘Renaissance’.

A book I hadn’t heard of but have now ordered, thank you 🙂

In Arthurian tales, I preferred the Romano-Celtic Dark Ages of Saxon invasion, more in line with King Alfred’s era. Mary Stewart’s trilogy of Merlin growing up in Wales, and learning medicine plus wizardry, or Jack Whyte’s Camulod Chronicles of fading Anglo-Roman society looking for alliances, resources, and smelting a sword from a meteorite.

I remember a sci-fi short story (can’t remember the name or the title) in which a chappie of Icelandic origin gets chucked back through time to mediaeval Iceland. Because the language has changed little, he can speak to them, but because the culture’s are so different, he comes to grief at times.

“The man who came early” by Poultry Anderson.

I’m sort of sick of the re-re-retelling of the Arthurian Legend.

I love narrative poems because they tell a story that I can appreciate, that I can follow, that I can engage with. I found all of those with ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’.

Tolkien’s next!

The perfect link between Beowulf and Chaucer.

As a big fan of Arthurian legends this is one of those stories it seems Iike I should have known.

If you want to understand the definition of an anticlimactic ending, read this one.

I remember studying it in college in my medieval English course (along with Pearl) and being amazed.

I read that shakespeare play for fun and I honestly couldn’t tell you what it was about lol!

I love this!! There’s so much I didn’t know!

Very insightful, thank you for the article

Thank you for the write up. What are some really good modern literature about the middle ages?

Sylvia Townsend Warner. The Corner That Held Them. This is an epic and very authentic-feeling story of the building and day to day management of a convent in medieval England. It was written during 20th c wartime, so the nuns come across as a little Women’s Institute at times, but that’s the point. Probably a perfectly good parallel. It’s such an excellent take on human nature, both under crisis situations and in the mundane. It has wonderfully developed characters and the loveliest conclusion of any book I’ve ever read.

Don’t know that one, thanks for the tip-off

You should check out the books of Judith Merkle Riley. Her books are all set in the middle ages and have supernatural themes. She can be quite humorous as well.

There is the Malazan series which is loosely based on classical medieval folklore and a pseudo Roman empire on a conquest. The Empire, while relying on magic and conventional weapons have access to “Moranth munitions” which are effectively explosive devices both hand thrown, crossbow delivered and used as landmines.

During the series the development of non magic, high casualty, weapons continues apace.

I recall a convincing account of the takeover of a distant empire of Lether, when the letherii army charges an advancing rogue Malazan force, the Malazans throw “stones,” the soldiers, of course are unaware of what these “stones” are!

The Spire by William Golding.

Marion Bradley is an incredible storyteller with impressive knowledge of the ancient Goddess based spirituality.

The interesting things about books and movies about the Arthurian theme is that there are always different perspectives, and different characterization.

The Mists of Avalon is epic fantasy at it’s finest. Wish more people read it.

This is supposed to be a book about strong women, and for the most part, it is. But they are all written in such a way that I came away from the book not liking any of them, and thinking they all deserved their ends.

I remember reading this book at the bell concerts my father used to take us to when I was a girl. I was maybe twelve or thirteen, and I’d sit on a blanket spread on the grass and loose myself completely as the bells chimed in the background.

I watched the miniseries version all in one night with my old roommate, and loved it. I also really liked the concept of re-telling (pretty much re-writing) the Arthurian legends from the point of view of the women.

Loved this book so much when I was younger.

Spenser is suspiciously good at evoking sins like greed, lust, and despair.

Yes, haha! What I find especially intriguing is Spenser’s ability to communicate meaning on several different levels all at once.

This article is quite expansive and informative. I’d never heard of Hesiod’s story about the nightingale. I’m glad I know it now.

The way it moves from era to era, citing multiple works of literature and their similarities and connections, supports the overall theme that part of fantasy writing is “the adoption of old myths…into modern understanding”.

There are some spots where there appear to be errors of syntax and grammar, such as “more Christian written Arthurian legends”. These interrupt the flow of one point to the next and make it more difficult to understand and follow the argument.

Ack, the mid-ages. If you haven’t read Connecticut Yankee because you think you learned enough about it from that criminally awful movie, you ought to give it a try. It doesn’t turn out quite like you’d expect. In fact it turns out pretty much like a whole lot of history that played out decades after it was published – and is still playing out today. That in itself is impressive, but what really impresses is how accurately Twain fingers the culprits.

The older I get, the more A Midsummer Night’s Dream becomes my favorite Shakespeare play. It’s a complete merciful escape into a magical and dreamlike woodland world.

The qualities of honour, sacrifice, and martyrdom are still evident in today’s fantasy writing from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Old Celtic legends have been passed on through generations with stories like Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ and ‘Macbeth.’ Perhaps drawing from these ancient sources still entertains readers and provides moral and ethical lessons for all age groups.

My favorite part of Midsummer Night’s Dream play was the play within the play.

Same here. The mechanicals were hilarious, they are the only reason that this play was a comedy.

I really enjoyed reading this article! It would’ve been nice to see some more modern comparisons though. I know there are many books and other types of literature that include mythology and elements from the middle ages/renaissance.

This is comprehensive article and beautifully written. There were several excellent observations that reminded me of the massive amount of superhero movies that clearly tap into the many principles of protagonists and plots that began so long ago. Thanks!

Great article! It was very informative and I think you included some great sources. The article was wonderfully written, and I loved the images that were included.

Definitely interesting that the Arthurian legends experienced a bit of a revival in the mid-20th Century. Nice job!

I’ve always loved the Arthurian Legends. Great article.

I really loved this article… King Arthur

I enjoyed this is an interesting collation ‘fantasy’ traditions! Self-awareness about the relationship between confabulation and representations of the world as it was perceived is an area that demands rich context. I wonder if the Pre-Raphaelites have made the fantastical qualities of the premodern world seem too familiar and contemporary? Does our eagerness to unify texts in a genre going back to “the very beginning (and beyond) of recorded language” cloud our understanding of what people were actually trying to say in the past? In both cases, the answer helps us to make sense of contemporary fantasy because hindsight, not history, is what tends to influence culture.

As someone studying English Literature at the University level, I’ve had a lot of encounters with Medieval Literature. It is truly fascinating how we can better understand past societies by looking at their stories, myths and legends.

What always fascinated me the most was their portrayal of the Heroic conduct. Beowulf, for example, is one of the first English epics, and it is PACKED with action. The hero fights monsters and dragons for glory, receives treasures and fame, takes part in massive feasts and celebration, and eventually dies in an Heroic manner. A story that you would think might be boring because it came out in the Middle Ages is actually the basis for most of our Romanticized ideas of what the Middle Ages were like. Knights, Queens, love affairs, betrayal, deceptions… Medieval Literature often reads like a soap opera drama.