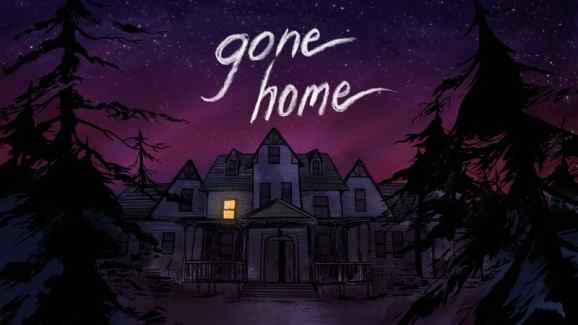

Gone Home and The Stanley Parable: Story Exploration and Agency

Games such as Phoenix Wright and LA Noire where gameplay takes a backseat to story have existed for a while – games where there is no real punishment for losing and you only complete minor challenges to move forward in the story. Recently, story exploration has emerged as a fully fledged genre. More like interactive stories than action-packed RPGs, story exploration games like Gone Home and The Stanley Parable have captured the hearts of casual gamers across the world.

However, Gone Home has faced scrutiny from the more hardcore crowd who don’t think it’s a real game. The Stanley Parable has not dealt with the same criticisms – perhaps because it didn’t reach the same level of popularity as Gone Home did, but also perhaps because of its features. This brings attention to a different question about these games. Rather than deciding whether or not story exploration games are ‘real games,’ it could be more interesting to figure out what differentiates story exploration games from movies or TV shows.

Plot

Almost every game in existence has a plot, and the plot is the entire point of story exploration games. For a lot of players, this means the experience is no different from sitting back and watching a movie; this is why it’s important that the plot be immersive. The player must have some control over story progression or else it ceases to be an interactive experience. This is where many criticisms of Gone Home come in – you move through the story in a linear way (which is of course not unheard of in video games, but it creates a weakness when you are doing little else but move through a story). You can explore any room you choose but in many cases a key or code that will take you to the next section of the house is in the last room you visit. If you miss a hidden item , you will learn less about the story, but there is nothing you can do to change its outcome.

The Stanley Parable, on the other hand, has an entirely nonlinear plot. The order in which you discover the various ‘endings’ it supplies is entirely up to the choices you make throughout the game. It comes with multiple possible endings, some of which a player might not even discover until they’ve played the game a few times through. The storyline follows the protagonist, Stanley, around as a narrator attempts to guide him through the story. If you deviate from what the narrator tells you to do, the narrator becomes frustrated but must follow you as you choose your own path. This affects the perception of the game – if you obey the narrator your first time through, you get a boring but positive ending, and this will shape your interpretation of the rest of the game differently than if you completely disobey the narrator at first and end up in one of many surreal, existential positions you will experience.

Gone Home has a moving plot, but the player can become impatient when they don’t discover anything of interest for a long time and the game can feel like a chore, something that could easily be viewed on a screen instead. The Stanley Parable allows the player to shape the experiences of their playthrough in a way that doesn’t strictly relate to completionism, and this makes for a truly interactive game.

Emotion

One of the goals of games in the story exploration genre is to invoke emotional or personal reflection via the story itself. Gone Home uses plot effectively to induce emotion. It begins when the protagonist returns home from a summer vacation to find her house empty and her parents and sister gone. Playing through the game reveals the problems her family has been struggling with in secret for a long time. Many moments are relatable and very touching, but you still witness them as a bystander. You are playing as a character who already has set values and interests and relationships that the player doesn’t share. The emotions caused are on level with those you might feel watching a sad movie, but your involvement doesn’t contribute to them at all.

The Stanley Parable creates emotion using the player’s own mind. You can make your own choices about what path to follow through the game, but are simultaneously told that you have no free will. This can invoke genuine existential questioning in the player about the choices they make in real life. If the player only finds a few of the endings or is not interested in big philosophical topics, though, they may just be confused by the game rather than involved.

It is necessary for writers of story exploration games to go beyond the level of emotion felt when watching a favourite TV show or reading a book. Emotion in such games must be experienced directly by the player as a result of their actions, and Gone Home doesn’t do this. Its story is emotional but some players may wonder why they have to bother controlling the protagonist. The Stanley Parable potentially makes the player question aspects of their lives, but the emotion it invokes is not accessible to everyone, especially on first playthrough. Both Gone Home and The Stanley Parable have emotional aspects, but they also have failings. All players should be able to enjoy the emotional parts of a story, and feel as though they have some stake in the characters’ lives.

Gameplay

The main difference between a story exploration game and other forms of media is, of course, its gameplay. Any puzzles/obstacles encountered add to the argument that you are accomplishing something by playing the game, that this is an experience you could never find elsewhere. Gone Home’s gameplay follows a standard point-and-click formula: almost any object lying around in the house you are exploring can be picked up and examined to reveal something about the story. To a certain degree, this affects your involvement in the game. Different play styles lead to different experiences in that if you rush through the game without looking at everything, you will receive a very shallow version of the story, but if you examine every object you come across you will get a fully fleshed out story about yourself and your family. Occasionally, you face the obstacle of a locked door or safe that you must find the matching key/combination for in order to move on. This forces you to explore the house in more detail and keeps you from dashing through the game without taking time to interact with it.

While The Stanley Parable has an immersive plot, its gameplay is limited. You are in control of the plot moving forward, but you can do little else besides walk and look around. This is in keeping with the theme of the story, which is about whether free will exists, but it can still lead you to feel as if you are just going through the motions. This is particularly noticeable in a few sections that either take place in endless loops or long sections of walking where you have nothing to do other than listen to the narrator. Certainly the story is interesting, but it can be tedious to walk in circles for 5-10 minutes while listening to somebody talk.

Neither game has much gameplay or thought required from the player, but Gone Home makes the effort to have some minor obstacles present so the player doesn’t fall into repetitive motions.

Agency: A Determinant of Game Status?

So why does Gone Home get so much more flak than The Stanley Parable? Both feature similar gameplay styles and developed stories and emotions, and both are stronger than the other in some areas. But while The Stanley Parable has been widely praised for its innovative story and unique style, Gone Home has been put under a microscope to prove it is not a game. At the end of the day, this appears to be because Gone Home doesn’t need interactivity to tell its story. Many players would have been happy to sit back and watch the story unfold without lifting a finger. In that sense, the player has little to no agency. Yes, you have the option to miss out on certain collectibles and parts of the story, but you are always moving toward the same goal. Multiple playthroughs provide the same experience, and after a while, it gets repetitive moving room to room doing not much aside from opening doors, turning on lights, and picking up loads of benign objects to see if they will give you any information.

The Stanley Parable is vastly different. It is nonlinear and you are entirely in control of your game experience. Like Gone Home, it does include set plot points, but you can change the order you experience them, ultimately defying what the narrator tells you in-game that your set path is. This puts gameplay power directly in the hands of the player and makes them feel like they have a stake in continuing the game even if they are simply changing the order in which they play through several different micro-narratives. This alone seems to have saved the game from going through the same criticisms that Gone Home suffered from. Despite The Stanley Parable trying to prove you have no free will, by presenting the player with choices deliberately designed to make you feel as if you are defying the written story, the game gives the player a sense of agency and control which is not found in many games in the genre. It is possible that this agency alone freed The Stanley Parable from becoming the target of the more narrow-minded sections of the gaming community.

Video games are constantly evolving as a form of art. New genres emerge all the time, and as games get put out faster and faster, developers and writers must make new innovations to keep games fresh. This is where story exploration has started to flourish – it allows writers to create in-depth stories that might be popular as a novel or film and put them into game form.

Arguably, if story exploration is to find success as a genre, it must include elements to differentiate itself from media that is watched. Gone Home includes plenty of environmental interactivity but the story involves little input from the player, which has invited criticism despite the game itself being enjoyable. The Stanley Parable goes above and beyond to create an environment where the player feels in control of their experience, but have a limited ability to interact with the environment. However, their issues don’t mean they can’t be considered real games. Gone Home is linear, but so are many contemporary action/adventure games. The Stanley Parable may have very little real gameplay, but trying to find all possible endings still creates a challenge for the player. Despite their issues, story exploration games hold a lot of potential and to find true success, writers of the genre must create a story where the player feels at home and in charge.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I normally don’t like narrative driven games (even the Telltale games don’t do it for me), but I really liked Gone Home. The story is great, but you, the player, have to piece it together as you discover items in the house.

It’s amazing how many light bulb moments I had when putting together certain details that escaped me previously. I honestly think the shorter length is one of the game’s assets. If the game went on much longer, I would have felt the story drag, but it never committed that sin. $20 is a bit steep for a four hour game that I may not play again, but I have no regrets. I’ve spent much more on games I regret, several times over in my life.

I managed to snag the game on a steam sale, so as far as I’m concerned it was worth every penny! I agree it’s a great game narrative wise and I have no problem with the short length. I’ve always found it frustrating that there’s such a debate over whether or not it’s a ‘real’ game.

Both of these are amazing games. Don’t let anyone deter you.

I believe Gone Home is significant for its storytelling as it weaves a unique, unconventional and emotional narrative in ways that just aren’t possible in other mediums.

The Stanley Parable has some of the best writing it has ever been my pleasure to experience.

Agreed! I think they’re both great games, so it’s a bit of a headscratcher for me to see so much criticism of Gone Home and not the other. They’re both early entries into a genre that’s just picking up steam and so they’re very useful as a critical lens to examine the genre, but I enjoyed every moment of both.

These are fine examples of how the video game medium plays a role in Postmodernism, and artistic endeavors in general. It raises the bar for creativity and narration in a medium that is plagued with cliches and predictability.

This game sounds like it is weak on ludology in a classical sense. With much of the game serving as a puzzle pieces together in the players head.

The criticism from players come from the fact that for the most part the debate between gameplay and story has been won in the west. Games like these are trying to turn things around so things can even put like they are in Japan on which dating sins are quite popular.

While I think the dating sim won’t catch on in America I do think there format would benefit many in the game playing community, that want something to that they can interact with and challenge them. Something that doesn’t require long hours of button mashing and more story than an angry birds has to offer.

Not really a “game” but amazingly interesting for a few hours.

These are more art than a “game”. But i still found it was a few hours well spent.

The Stanley Parable actually made me physically sick. The main purpose of this game is to force the user to relinquish all control. This game is a complete waste of time and money (the narrator actually conveys this message to you in-game several times).

Impressive how these games played with my feelings and emotions. So surreal.

Gone Home was such a wonderful game. I wasn’t expecting to be so fully absorbed in the short story, but I was completely obsessed with finding every hidden note and audio journal entry, and I played for 4-5 hours straight. It really shows that games can be more than just action and violent FPS’s.

just finished playing stanley parable. I loved it. I was laughing most of the time.

My favourite ending in Stanley was the Broom closet ending!

The cliches in this GH… As a gaymer (gay gamer), they were fucking painful. Not to mention it was insulting that they threw in the lesbian love shit-storm just to be “current.” Quit using people’s sexual identities and turning it into cry-baby Dr. Phil drama stories. Our lives aren’t that overly and laughably dramatic… Trust me.

As a member of the LGBT community myself, I do agree that it was over the top, but there were a lot of moments I could identify with. As far as it being thrown in to be current, I was under the impression that the developers were members of the community, although if I’m wrong about that it does change my overall impression of how much thought was put into the story.

I wish that would release these for the PS4.

Story-driven games have always interested me, although I don’t play them. In fact, I watch gameplays on Youtube and treat it like a TV show! (I’ve done that with Phoenix Wright and Dangan Ronpa).

I think it’s interesting you state that storytellers need to make the player feel the emotions based on their own actions. That definitely makes games different than TV shows, as TV shows are only immersive because you are watching it from a perspective of an outsider – you’re not actually in the show to interact with things.

Great article!

Other developers should consider taking some inspiration from Gone Home’s story execution, as it has definitely raised the bar for videogame storytelling.

I loved that in Gone Home, it felt a bit like the classic MYST to me in its presentation, and I loved the 90’s nostalgia.

However, I feel this game wouldn’t have gotten the attention it has, and possibly not the high praise from critics, if not for the relationship subject matter with Sam. I felt they used her and her friend’s feelings as a gimmick more than as an integral part of the story as a whole.

Just my opinion obviously.

I don’t get why you’d call the relationship matter a gimmick when it’s obviously the main path the story’s going in

90’s Nostalgia?! Way to make us feel old!

Just played “Gone Home” through for the first time and I enjoyed it, but thank goodness it was only as long as it was. The premise was wearing quite thin by the end.

The Stanley Parable is simply fantastic.

The exploration part of the games are fantastic. I had fun looking and reading the small details.

These games sound amazing. I recently started gaming on Steam, and I was surprised by how many negative reviews I saw for “Gone Home,” though.

I really wish your character could run in gone home.

My overall experience of Gone Home was underwhelming. I thought the subject matter isn’t really something evocative as it tries it to be. As I progress further, I’m getting less captured by the game; my interest is slowly losing. I felt like the game just made me go round the circle to find out something that I already know halfway in the game. I think it misses something that keeps your attention going. I understand how the critics and reviewers went gaga over this game as something like this is not a common sight in the industry. It is a refreshing game in an industry convoluted with shooter-action games.

Gone home is not a video game. It’s a movie.

Finally got around to playing Gone Home, and from the moment I saw that attic entrance, I was dreading what I would find when I eventually got in there. I’m a run & gun gamer, but I gotta say, I was shocked how this game pulled me into the story.

Just played Gone Home and what a joke of a game. I mean, it’s not bad, but after the end it just felt so cheap and like such a waste of time. The reason being is that the game tricks you into thinking it’s a horror game for its entire runtime, with creaking and moaning audio cues, the sound of the storm, etc. all this creepiness, then visual creepiness such as a house that looks ravaged and abandoned, paranormal and satanic stuff, secret compartments and passages everywhere, the house being known as the ‘psycho house’ or something, hints at not only the paranormal but also suicide and it just goes on and on and on and then all is revealed and it’s just… “ha, got ya, thanks for paying”.

and it sucks that I have to say that because the actual real story behind all the fake b.s. covering it all up is nice and sweet and simple and relatable, just about a kid being different and making a decision.

But while the game is decent, it spends its entire runtime promising something, and then when all is revealed it just feels like it totally tricked us, and for what? Why make us think it’s a horror game? They easily could’ve toned down the horror hints/elements a TON, and just made it a more straight up adventure/mystery game (which could still have a sense of dread at times, naturally) and with that the game wouldn’t leave on such a sour, cheap feeling note, like it just pulled a fast one on us.

I wish they either toned down the horror element a ton, because it really is needless and cheap, or they had actually made it legitimate horror and not just a trick.

I’m a run & gun first person shooter console gamer, but

when Gone Home got game of the year I thought, such an odd little game, I gotta see what the big deal is. Purchased it online put on my headphones and sat down to

play. Great experience.

Gone Home is a fun and an interesting game. It didn’t start picking up until the velociraptors appeared, then MAN was it crazy!

While I understand your argument that these games are a new development, I’m of a slightly different interpretation. The “visual novel” style games (popularized in Japan, but with a few shining gems in the western world, like 999) really tends to meet much of the criteria placed here. I’d say these sorts of games likely originated around the N64 or Gamecube/PS1 era, specifically because the processing capabilities of the machines then reached a point where extended animations or soundtracks could be inserted. Of course, you’re right to differentiate these sorts of games from anything in that era, because an N64 could never support the complexity and design of something like The Standley Parable, but I imagine that a dedicated researcher would be able to trace some sort of line back. Unfortunately, I’m not that researcher.

Nonetheless, good read!

Great article. This reminds me of discussions about games like Dear Esther and The Path and whether they constitute as games at all. Because the genre and its manner of constructing narratives is still changing and expanding, I’m ambivalent on deciding 100% just yet. I will say that I did enjoy Gone Home and The Stanley Parable a great deal.

I remember first completing the Stanley Parable for the first time just doing everything the narrator told me. After a short time I would stumble upon an interpretation for that ending that changed everything for me and from that point forward I couldn’t look at anyone of the endings as less than meaningful. I believe as you pointed out in your article the interaction the player has to the story and experience of the game is what draws the lines we have. I’d best equate it to being on a road trip: does it make you want to take the wheel and drive? Or are you just content watching the world go?

I didn’t think Stanley Parable and Gone Home really were the same kind of game.

They look and play similar and scratch the same itch for fans of this type of exploration games but the devil is in the details.

In fact the Stanley Parable incorporates the experience of playing Gone Home as well in its self-reflective ambitions. And that in my opinion is why it didn’t face the same backlash as Gone Home, it is trying its argument for videogames to not just be considered an equal form of art but just as potentially effective as the greatest art pieces with a more layered and intellectual approach. A solid story like in Gone Home can be told in many ways, but the parable of Stanley’s parable just won’t work if you were to just listen to it, read it or try to passively watch it on a screen.

the real underlying issue people have is feeling not getting their money’s worth with such short playtimes, Stanley Parable was also always a little cheaper for more content overall, let’s keep it simple.