His Dark Materials: Conflict, Justice and Mental Health

Young Adult Literature (YAL), particularly fictional literature, can provide inspiration, escape, fun, and non-didactic guidance for daily life. As such, it is an enormously popular genre. Despite its focus on ‘the young’ (most often a teenage protagonist), YAL has garnered the attention of readers of various ages who vicariously live, and learn, through characters’ actions, plot or theme. This form of escapism through creative worlds, such as the mythic fantasy universe or multiverse, is one of the reasons fictional YAL is so captivating … It is a fantasy or science fiction world that can help readers learn more about themselves in the real world.

The focus of this article is ways in which YAL provides guidance to the reader. An escapist narrative: a fun and creative method, it is useful as a reframing and illumination tool. In particular, to reframe and illuminate messages of internal/external conflict, social justice and subsequent mental health impact for a young adult audience.

From a literary critical perspective, narrative has long been conceived as social critique. More specifically, as a mediator of various kinds of justice. When readers of fiction unconsciously absorb messages from the stories they read, they use them to structure and make meaning from the text. Thus, YAL – particularly mythic fantasy literature that describes the hero’s journey – can help reframe and illuminate messages that young adult readers can incorporate into their daily lives. For example, Oziewicz states:

‘I have continued to be struck, time and again, by how profoundly plot structures, theme – and, as I now believe, the very appeal – of young people’s literature are predicated on the dream of justice … YA speculative fiction ought to be recognized as one of the most important forges of justice consciousness … with clear implications for both literary … [and psychological] practice’ (Levy, 2016, p 225).

Whilst all Young Adult literature can potentially provide a ‘window and mirror’ to particular issues, this article supports Victoria Flanagan’s (2014) views of fictional literature. A senior lecturer in English at Macquarie University, Flanagan explains there is a general public misperception that fictional writing is inferior to realist writing because it is commonly associated with children and imagination. Operating through metaphor, allegory or parable, however, the unfamiliar becomes familiar. Metaphors allow for complex reader interpretive processes – allowing fantasy fiction to explore multifaceted social and psychological issues in ways that are less confrontational than realism. Fantasy fiction takes place in a world distanced from social reality, but directly comments upon real-life issues, often mediated with humour. As such, mythology-based fiction and legendary stories can be far more interesting than non-fiction self-help books.

Fiction, Character and Psychological Presence

Characters play a central role in YA fantasy fiction, as do the monsters they fight. Vampires, zombies, werewolves or other mythical creatures may be considered psychological allusions to aspects of readers’ own lives. Though some works may be unsuitable for mental health and justice reframing/illumination, they do involve aspects of life and human nature that, according to Bodart (2011), some adults prefer to keep hidden. They are important, for example, to provide literal examples of how ignoring life’s problems won’t make them disappear, and demonstrate that ignoring danger puts a person at greater risk of harm.

Numerous contemporary authors write YA fiction stories that incorporate mental health, internal/external conflict or justice into their narrative. A few popular examples include: Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Revis’ A World Without You, Kinsella’s Finding Audrey, Glasgow’s Girl in Pieces, Arnold’s Mosquitoland, and Niven’s All The Bright Places. There are many others. Modern-day fiction authors generally provide a reasonable portrayal of conflict and justice issues, or subsequent mental health problems; but YAL that articulates the mythical hero’s journey also takes a young reader on a hypothetical and metaphorical adventure in which they connect with illusory scenarios and characters. The heroic journey narrative can be used to reframe and illuminate the young reader’s everyday reality through the mythic hero’s ‘reality’. This includes the individual’s interpretation of their own mental health experience, conflict or social justice issues in the reader’s life.

According to Goldsmith, Heras & Corapi (2016), young people can use literature as ‘windows and mirrors to help them reflect on their own experience and learn to empathise with others’ (p. 3). Thus, stories become the entrance through which children and youth learn to connect with one another, the author, subject matter, ancestral history as well as themselves. At the same time, the reader can learn positive strategies such as effective ways of coping, ways of resolving conflict, and enhanced understanding of human nature.

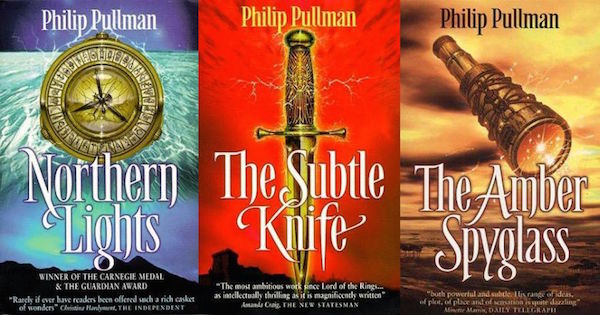

For audiences 12 to 18 years approximately, the fantasy literary category based on mythology and legendary heroes is rapidly-growing. The significance of YA fantasy fiction (as evidenced by their popularity), and the use of narrative methods to reframe and illuminate mental health, justice and conflict, coupled with innovation, raises awareness of what is already happening in the young reader’s mind or life. To explain this further, a popular mythology-based fantasy novel has been selected. Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy can be viewed as an expose’ of mental health, conflict and justice secrets and strata.

His Dark Materials

Pullman’s Young Adult epic, His Dark Materials (1995-2000), is a classic work of fantasy fiction predicated on myth. Moreover, it challenges some of today’s most important justice issues and is useful for mental health reframing and illumination. An ambitious crossover work, it offers young and older readers much to enjoy and contemplate. Pullman’s coming-of-age story depicts two young protagonists who aid each other’s katabatic journeys (descent to hell and return). Fraught with difficulties and trials, all is overcome with persistence and love. Will and Lyra’s Arthurian quest across multiverses (multiple universes) is represented by social support seeking: evidenced through a metaphysical ‘connection’ with others (Iorek Byrnison, Farder Coram, the Gyptians and others); with self and spirit (Pantalaimon and other shapeshifting daemon); and to the natural world of the Aurora and the magical allusion of Dust, strange elementary particles under investigation by Lord Asriel.

In keeping with Carl Jung’s premise of the dual nature of humanity, Pullman’s series reframes the ordinary and extraordinary as part of each character’s journey. Good and evil are not viewed as opposites in Pullman’s work, or in Jung’s view, but as necessary complements. Contained within Pullman’s fantasy script, this deliberate pairing of elemental opposites (such as extreme sadness vs extreme happiness) adds a depth and verisimilitude to the text. Philosophical and religious aspects of self-introspection are beautifully disguised, reframed and illuminated within this popular literary narrative. Like other YA fantasy fiction grounded in myth and legend, such as the Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings series, it is also a tale of fantastic adventure, speculative cosmology and a philosophical love story potentially leading to greater self-awareness when analysed.

Conflict

Pullman describes internal conflict in Northern Lights (the first book in Pullman’s trilogy). Its film debut entitled The Golden Compass commences with a scene in which Lyra is in conversational conflict with her daemon (the corporeal manifestation of her own soul). The creature is called Pantalaimon (Pan). In the Retiring Room Pan states, ‘It’s none of our business. And I think it would be the silliest thing you’ve ever done in a lifetime of silly things to interfere. It’s nothing to do with us.’

‘Don’t be stupid,’ Lyra responds, saying she cannot just sit and watch Lord Asriel be given poison, to which Pan replies, ‘come somewhere else, then’ (p. 9). Pan’s attempt to encourage Lyra to ignore an important social justice issue reframes and illuminates for the reader Lyra’s Shadow, and the importance of maintaining courage in conviction within an internal fight. Unable to ignore others in a conflict situation, Lyra highlights to a potential young adult reader a restorative justice practice of showing empathy to Lord Asriel, irrespective of how she feels about him. Lyra calls Pan a coward (indirectly acknowledging this Shadow aspect of herself). Her conscience would not allow her to idly watch.

Justice

Justice notions (particularly the concepts of fairness, restorative justice and reconciliation) permeate Pullman’s narrative. His creative work usefully describes mental health issues and justice messages. For example, Will almost has a moment of violence when thinking about his past, but he learns to control himself by focusing on continuing his journey, by calming down, taking a deep breath and distancing himself from the violence. Deep breathing as a calming strategy to promote awareness of Self, retributive vs restorative justice and effective ways of coping with conflicting emotions are reframed and illuminated through Pullman’s exemplary text.

In Book 2, Lyra is talking with three boys and a girl, sitting in pools of water in a sunlit harbour, conversing about Spectres (a psychological allusion to depression):

‘If you can’t see ‘em, you’re safe,’ said a boy. ‘You see ‘em, you know they can get you. That’s what my pa said, then they got him. He missed them that time.’

‘And they’re here, all round us now?’

‘Yeah,’ said the girl. She reached out a hand and grabbed a fistful of air, crowing, ‘I got one now!’

‘They can’t hurt you,’ one of the boys said. ‘So we can’t hurt them, all right’ (The Subtle Knife, 2007, p. 145).

In book 3, Will is also in conflict with the great bear. In keeping with restorative justice, as opposed to retributive justice practices, he reframes and illuminates the notion of fairness:

‘It’s not a fair contest at all. You have all that armour, and I have none. You could take off my head with one sweep of your paw. Make it fairer then. Give me one piece of your armour, any one you like. Your helmet, for example. Then we’ll be better matched, and it’ll be no shame to fight me’ (Pullman, 2007, p. 106).

In Pullman’s trilogy, conflict, justice and shame are illuminated for the reader. Lyra finds herself entangled in a cosmic war between Lord Asriel and the first angel to come into being – The Authority – and his Regent, Metatron. As Lyra and Will fight for social and personal justice, they sacrifice their personal and mental health.

Mental Health Messages

In book 1, Lyra’s anxious feelings are beautifully reframed and illuminated:

‘Her main thought was anxiety, and it wasn’t for herself. She’d been in trouble often enough to be used to it. This time she was anxious about Lord Asriel, and about what this all meant’ (Pullman, 2011, p. 10).

Such a fragment can be used to help a reader to consider, consciously or unconsciously, how Lyra’s anxiety symptoms are presented … and why.

At the beginning of Book 2, The Subtle Knife, there is a scene in which Will is asking Mrs Cooper to take care of his mother for a few days. In describing her dishevelled appearance, a key indicator of a mental health condition, Pullman writes:

‘Mrs Cooper looked at the woman with untidy hair and a distracted half-smile … Mrs Parry, Will’s mother, had put make-up on one eye but not on the other. And she hadn’t noticed. And neither had Will. Something was wrong’ (Pullman, 2007, p. 2).

Will’s character also reframes and illuminates a mindfulness activity, a psychological mechanism in which the person becomes immersed in the present, when talking with Giacomo Paradisi about the subtle knife:

‘It’s not only the knife that has to cut, it’s your own mind. You have to think it. So do this: put your mind out at the very tip of the knife. Concentrate, boy. Focus your mind. Don’t think about your wound. It will heal. Think about the knife tip. That is where you are. Now feel with it, very gently’ (Pullman, 2007 p. 182).

Will’s character was also very upset thinking about his poor mother – ‘the poor frightened unhappy dear beloved, he’d left her, he’d left her …’ (p. 182) indicating some separation anxiety. Using pet therapy to reframe and illuminate an effective method of coping with his feelings of desolation –

‘He brushed the back of his right wrist across his eyes to find Pantalaimon’s head on his knee. The daemon, in the form of a wolfhound, was gazing up at him with melting, sorrowing eyes and then he gently licked will’s wounded hand again and again, and laid his head on Will’s knee once more’ (The Subtle Knife, 2007, p. 182-183).

Perhaps the greatest example of Pullman’s mental health reframing and illumination of depression is at the beginning of book 2, (1997) The Subtle Knife:

‘She felt a nausea of the soul, a hideous and sickening despair, a melancholy weariness so profound that she was going to die of it. Her last conscious thought was disgust at life …’ (The Subtle Knife, 1997, p. 329).

Just as Will and Lyra journey through the multiverse to save human souls in His Dark Materials, mythic/heroic YA fantasy literature can extend readers, to take them on a psychological exploration of the archetype of Self. It is proposed in this article that reframing and illumination exists through an educational and enjoyable exploration of the text. As such, the narratives’ usefulness as a reframing and illumination tool could account for why YA fantasy fiction grounded in myth and legend is enormously popular among a young adult literary audience. Young (and older) readers innovatively learn about conflict, social justice and mental health; personal struggles and ways of coping with issues reframed and illuminated through archetypal and mythical mores. The protagonists’ sometimes solitary walk, through caves and other difficult terrain in Pullman and other fantasy authors’ coming-of-age novels, is reminiscent of our own heroic journey.

Works Cited

Bodart, J. R. (2011). They suck, they bite, they eat, they kill: The psychological meaning of monsters in Young Adult fiction. Maryland, US: Scarecrow.

Flanagan, V. (2014). Children’s fantasy literature: why escaping reality is good for kids. The Conversation, March 3, Retrieved http://theconversation.com/childrens-fantasy-literature-why-escaping-reality-is-good-for-kids-22307.

Goldsmith, A. Y., Heras, T. & Corapi, S. (2016). Reading the world’s stories: An annotated bibliography of international youth literature. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield.

Levy, M. (2016). Justice in Young Adult speculative fiction: A cognitive reading by Marek C. Oziewicz (review). Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 41(2), 224-227.

Pullman, P. (1995-2000). His dark materials. Book Series. London: Scholastic.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I like my wild, adventurous fantasy tales as much as the next fella and this falls into my cup of tea!

The many themes presented in this trilogy are ones that can easily be translated into our own worlds.

The movie was pretty disappointing!

True Om. Cake – the movie was not an accurate representation of the complexity of the book trilogy. Thankyou everyone for your comments.

My favorite YA novel is House of Stairs by William Sleator (1974). It is not well-known but remains my all time best recommendation with similar themes about mental health, conflict and social justice.

Pullman’s novels are amazing. Perfect reading for a child or teenager.

The first book was great but the second book became such hardcore evangelical anti-theism it was like I was in the polar opposite of a church. An atheist does not believe in god, an anti-theist thinks it is their mission to tell everyone else they should not believe either. Color it however you want that is proselytizing. I’m not religious and I don’t like those for or against religion beating me over the head trying to convince me their way is ‘right.’ Look I just wanted a good story without the diatribe. I just couldn’t take it any more and put the 2nd book down and never looked back. As an agnostic I spend spend about .0001% of my time thinking about religion, I have enough in the here and now to concern me and I don’t need to be ‘converted’ by anyone, I’m fine as I am. A shame to because the world was fascinating, just not enough for me wade through all that.

I’m an athiest and I disliked the second (or was it the third?) book for not only the far too heavy religious (or anti-religious) overtones, but moreover for explicitly killing God. Why, one wonders, is there a God to be killed in the first place?

I’m so glad I read it when I was young enough not to compare it too much to our real world.

Had the books not dealt with the themes they did they would not have been as powerful a read or as celebrated.

The best literature puts new ideas into your head. Harry Potter reworked old ideas but Pullman came up with an innovative trilogy. Some of the storylines did become difficult to follow in the later books but it did not detract from the fact that the Dark Materials made me think quite deeply whereas Harry Potter seemed a good read but that was it.

I loved the books, the film was very disappointing though. These are very complex multilayered books which would be better suited to television.

I always thought they should have “Peter Jackson”-ed the whole series of films when they had Daniel Craig, Nicole Kidman etc.

I LIKED the Golden Compass. It had its good moments, but lost the point of the book bigly.

If you weren’t familiar with the source material or didn’t mind the liberties they took with it, then it’s not a terrible film. But if they’d kept true to the series some of us believe that it would have been a success, rather than a flop.

The cast and art direction were top-notch. The problem lay in the script and giving it to a first-time director.

These might be called the Anti-Narnia books, which is about as much as they should be dignified with.

They encourage children to be themselves by fulfilling all their desires. Ie, freedom as being able to do whatever you want whenever you want. Rather than the religious emphasis on liberty as being able to overcome one’s own desires in order to be fulfilled by giving oneself freely to another.

One is a highly anti-social ambition, and the other is the foundation of true relationship. Which do you want for your kids?

absolute nonsense, are you sure you’ve read them? they’re a classic ‘quest’ tail, emphasising truth and kindness, against mindless authoritarianism that kills children and hope.

The film was disappointing, as most adaptations of complex books are, and it pulled its punches so as not to offend.

Love the books and I enjoyed the film – flawed, but I thought some of the casting was great and it looked amazing. Pity the studio lost their bottle. At least a full series should be able to handle the scope of the books.

Incidentally, a friend and I once speculated on what the sequels might have their titles simplified to in order to be easier to sell in certain markets, in the same way that “Harry Potter & The Philosophers Stone” became “….and the Sorcerers Stone” and “The Northern Lights” became “The Golden Compass”

Think we decided “The Subtle Knife” became “The Blade of Power” and “The Amber Spyglass” became “The Amazing Telescope” 8^)

I’m trying to forget “The Golden Compass” movie, really I am. For now though, I content myself that it was better than the Twilight movies or Battlefield Earth.

It was such a let down because the cast was so bloody good, but the script and execution was so bad.

I was disappointed that they tiptoed so gingerly around the issue of the church

Thankyou everyone for your comments. Yes there was a strong anti-religious undertone, and yes the movie was somewhat poor and flawed, but this was not the focus of my article. I simply used Pullman’s book as an example of how mental health, justice and conflict messages can be reframed and illuminated through a Young Adult fantasy fiction text, grounded in myth and legend – and that which articulates the hero’s journey. There are numerous other examples that could also be used, like the Potter series, the Percy Jackson series, Lord of the Rings trilogy, the Narnia series etc. 😄

These are children’s books, not adult fiction, and they are not great works of literature, just simple stories of fantasy with traditional good v evil. I was sorely disappointed when I read them on friends’ recommendations. They certainly won’t match the epic storytelling of Game of Thrones, Breaking Bad etc.

Maybe you just went at them the wrong way. I read them as ‘books’ not children’s books or adults books, but simply as books. They were – and are – beautifully plotted, smart and satisfying. If you’re attempting to compare these with the books of Song of Ice and Fire (and comparing negatively), then I’m just assuming you haven’t read all of the Ice and Fire books…

Do you mean to say that all young adult fiction are simply “children’s books”? The best example of the genre really are examples of excellent storytelling, and can be read by any age.

The first book was excellent. The second less so. The third, very muddled in its message. I have re-read the first a few times, but the others only once, to reassure myself that they had little to say.

Totally agree. I really enjoyed the first and remember thinking ‘Wow’ at the fight between the Warrior Bears. The second was OK, but too little of Lyra and I missed out whole chunks of the final book; mainly the chapters relating to Mary (?) and the elephants on wheels.

Well, the film was ok until SPOILER ALERT

they left off the ending and ripped out the soul of the book! Typically bloody Hollywood need to have a happy ending rather than the true ending of the book that sounded a dark note and set up the final book nicely.

Also, whilst Lyra was exceptionally well cast, she wasn’t quite the tearaway that the novel depicted. Again, sanitised.

I enjoyed the first two books of the trilogy immensely but found the last one disappointing. It just felt a bit muddled compared to the clarity of its predecessors.

I felt the same way. I really enjoyed the first book – and read it almost half way through before realising it was meant for teenages. The second was almost as good but I felt the third one was a lot of ideas that he was trying to pull together not entirely succesfully.

Fantastic article Toula. I am not familiar with Pullman’s work, but I thoroughly enjoyed your analysis of his work. I’ve heard that John Green’s latest book, Turtles all the way down, deals with OCD — the disorder the author himself has long dealt with.

Thanks Tara. Contemporary fiction can also be very good for mental health reframing, but for an experience that transcends the everyday in order to reframe the messages, a mythic/heroic narrative through an alternate universe may be more useful than regular YA fiction. Would be interesting to find out the differences in reader responses. New grounds for research maybe?! 😄

A great article and you raise some salient points regarding mental health issues. As one who has dealt with depression, in the past, I can certainly identify with the feeling of ‘…disgust at life’, so well done.

As a fan of Pullman’s works I was very disappointed with the film adaptation. In my opinion it lacked the depth of the books and avoided the deeper religious issues. I’m pleased the rest of the trilogy remained unfilmed.

I believe that a lot of the best fantasy/science fiction/imaginary worlds stories are being written as YA these days. I know a lot of adults, including myself, who are only too happy to read them! And I think they can be as relevant to adult mental health as to youth mental health, I think.

A very interesting read! Its surprising how many YA books represent mental health issues within the prose. I haven’t read this tribology yet, thank you for the inspiration!

Wow, I just finished reading the trilogy for the first time last night, and this really does help me view the themes and ideas more uniformly! Thank you for verifying what I realized!