Madness and Selfishness in Lady Audley’s Secret

Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s 1862 sensation novel Lady Audley’s Secret is both addictive and troubling. Like a modern soap opera, the story follows Lady Audley as she fights to hide the secrets of her past from the family she’s married into. In the climactic scene of the novel, Lady Audley confesses to her husband, Michael Audley, and nephew, Robert Audley, that she has been hiding her true identity. She faked her own death in order to avoid her first husband, George Talboys, and marry Michael Audley instead. Lady Audley, or Lucy, reveals George Talboys left to seek his fortune in Australia, abandoning her, their son, and his marital duties. This prompted her to changed her name and commit bigamy to advance her place in society and protect her well-being. Upon hearing this confession, the men instantly assume she is mad.

Throughout the text, Lucy (as I will refer to her from here) displays many different instances of selfishness; abandoning her son, faking her own death, pushing George Talboys into a well, using Michael Audley for a rank in society, setting a hotel on fire. But does all of this make her mad? Or, is this selfishness just her way of surviving? In this article, I will argue that Lucy is not mad, but rather fighting for her own survival and relevance in the world. The men in the novel see Lucy as a threat to their way of life because she not only doesn’t follow the typical female duties of the home, but has also proved herself to be smart and cunning. She is someone who is able to trick people and get what she wants. Because Lucy has lied to get what she wants, she is dangerous. And a woman seen as dangerous in Victorian society is labeled mad.

Pity, George Talboys, and Motherhood

To explore what Lucy’s selfishness has to do with the claim of madness, we must look at all of the ways her actions benefit her throughout the narrative. First, and possibly most important, Lucy abandons her son to fake her death and take up her new identity. Of course, one could argue she does this to try to give her son a better life. However, she admits outright that she does not care for the child: “People pitied me, and I hated them for their pity. I did not love the child, for he had been left a burden upon my hands” (254). Here, Lucy expresses a lack of love for her own child. Victorian mothers were supposed to be perfect and love and protect their children no matter what. In fact, their only identity was being a mother. When Lucy rejects this notion, and chooses herself over her son, she is seen as mad.

In Angela Florschuetz’s “Madness as Domestic Defense in Lady Audley’s Secret and Jane Eyre,” she argues that women of the time were declared mad because the functions of wifehood and motherhood were so taxing:

“Irony and tension are created by the inference that the natural and feminine function of women puts them at risk for a malady that renders them inappropriate wives and mothers, yet this malady was, in fact, also considered a normal function of womanhood. The question arises—if all women are potentially madwomen, are all woman potentially unfit or unsuited to wifehood” (Florschuetz 66).

This is as if to say by Lucy simply being a mother, she is already mad. Florschuetz goes on to explain:

“The concentration upon madness and otherness which define both Lucy and Bertha serves to both exonerate and obscure the failure of men as husbands to provide for, protect and support their wives, as well as the failure of marriage itself as an institution to deliver to women what society promises them as their due for their submission to me” (70).

Part of the reason Lucy feels no connection to her son is because George Talboys abandoned their family and did not fulfilled his marital duties as the man of the family. He has left Lucy, her father, and their son poor, with little resources to fend for themselves. Lucy’s anger toward her husband could explain why she does not feel a motherly duty to her son:

“But when we came back to Wildernsea and lived with papa, and all the money was gone, and George grew gloomy and wretched, and was always thinking of his troubles, and appeared to neglect me, I was very unhappy, and it seemed as if this fine marriage had only given me a twelvemonth’s gayety and extravagance after all” (Braddon 253).

Here, Lucy explains that George ignored her in their marriage and she admits to being unhappy, something women were not allowed to acknowledge.

Florschuetz explains that there is often an anxiety in Victorian marriage that leads to madness: “These novels suggest an anxiety about Victorian marriage, in that the only way women can assert their rights and protect their rightful and ‘natural’ position in marriage is by committing violent acts of ‘madness’” (Florschuetz 65). Lucy’s violent act here is to abandon her life when George Talboys leaves and start a fresh new one. In doing so, she is choosing herself over her marriage and her child. In this violent act, she is escaping an unhappy marriage and the confines of motherhood, something that distracts a woman from herself. In abandoning her duties to her family, Lucy is abandoning her identity as a correct version of the Victorian woman. This challenges a man’s understanding of the type of emotions and opinions a woman can have in the family unit.

An Advantageous Marriage

After leaving her family behind, Lucy takes on a new name and meets and marries Michael Audley, securing a marriage with fortune and status. This time she has purposely looked for a husband with power. She explains, “I think I loved him as much as it was in my power to love anybody; not more than I have loved you, Sir Michael—not so much, for when you married me you elevated me to a position that he could never have given me” (Braddon 253). Lucy admits that her marriage to Michael Audley is better than her marriage to George Talboys. Michael Audley has elevated her to the place in society she wanted to be. This admittance is another act of selfishness. By marrying for power instead of to become a wife and mother, Lucy is disrespecting the institution of marriage. In her essay, “Taking Back the Pen: Sensation, Sanity, and Subversion in Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret,” scholar Kelsey Hatley explains that Lucy’s marriage makes up for her miserable first marriage:

“Her marriage to Sir Michael was everything she hoped for in her first marriage, and in marrying him she was actually trying to adhere to the conventions of her society by securing herself an advantageous marriage. She used her conventional beauty to marry a wealthy man and become the perfect housewife, and all of this was motivated by her fear of poverty. Her actions, those of hiding her past and of attacking George because he threatened her newfound security, were motivated by her intense fear” (Hatley 53).

Here, Hatley points out Lucy has found an “advantageous marriage,” one that has secured her protection. And that is something George Talboys could never give her. In embracing this new life, Lucy is erasing the pain of her first marriage. She is creating a life where she can put herself first. This form of selfishness shows once again how Lucy’s cunningness reflects the usual characteristics of a man. By seeking out a marriage for the sake of elevating herself, Lucy is embracing the madness of only thinking about her own well-being. She does not care about the well-being of the people around her. And, she is not allowing the men at Audley Court to define her: “The cultural myths regarding the disaster that would surely befall a woman who tried to define herself on her own terms, rather than keeping quiet and letting the men define her, were very prevalent” (24). In seeking a marriage for social and financial reasons, Lucy has created a life in which she can be whoever she wants to be. This disturbs her male counterparts because Victorian women were never asked about what they wanted or who they really were.

Hatley also makes mention of a very important part of Lucy’s narrative: her beauty. Lucy learned at a young age she was beautiful:

“As I grew older I was told that I was pretty—beautiful—lovely—bewitching. I heard all these things at first indifferently, but by-and-by I listened to them greedily, and began to think that in spite of the secret of my life I might be more successful in the world’s great lottery than my companions” (Braddon 252).

The word “bewitching” stands out in this passage. Lucy knows there is power in her beauty and she is not afraid of using it to advance herself forward. She knew from the moment she met Sir Michael she could easily marry him because he was attracted to her beauty and charm. There is danger in Lucy’s self-awareness. She is controlling every situation she finds herself in by entrapping men with her looks. It’s something she knows they can’t escape.

This bewitching of men is an act against men. And when women work against men, they are considered mad. Hatley explains the control Lucy has is not a sign of madness at all:

“Braddon uses a situationalist perspective and outlines the fact that Lady Audley is not, in fact, mentally ill, but rather her ‘madness’ is a product of her environment. Braddon uses this important distinction to then expose the faults in Victorian society” (51-52).

As a product of her environment, Lucy is merely using the only weapon in her arsenal to adapt to her changing situation. Hatley seems to be claiming that by exposing faults in Victorian society, Braddon shows madness as something constructed by men to control women. Lucy flips this script by using her assets to control her narrative.

Shame and Lucy’s Anger

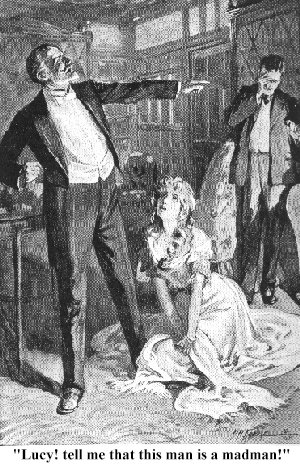

Lucy’s selfishness is observed by her male counterparts as she seeks to control them. Robert Audley tries to expose Lucy’s lies so he can proclaim her mad. In doing so, he is seeking a sort of revenge on Lucy for trying to destroy himself, George Talboys, and Luke. While Lucy is confessing to her life of lies, Robert observes her as a common criminal:

“It was impossible to see any of the changes in her countenance, for her face was obstinately bent toward the floor. Throughout her long confession she never lifted it; throughout her long confession her voice was never broken by a tear. What she had to tell she told in a cold, hard tone, very much the tone in which some criminal, dogged and sullen to the last, might have confessed to a jail chaplain” (Braddon 252).

Robert observes Lucy’s cold demeanor as she confesses to tricking his family. He notices that she never sheds a tear or changes the tone in her voice. In essence, he is shaming Lucy. Shaming her for acting like a man would. Scholars Heidi Hansson and Cathrine Norberg discuss this sort of shame in Victorian Literature in their piece, “Lady Audley’s Secret, Gender and the Representation of Emotions”:

“Shame is introduced as an emotion that Lady Audley, as the representative woman, should display but does not, whereas men are vicariously ashamed on behalf of the women in their charge. As a result, men’s shame is separated from their own activities and figured as a response based on their protective roles” (Hansson and Norberg 444).

The idea that Lucy has no shame in the wrongs she’s done to men shows she does not take anyone’s feelings into consideration. Her actions are to only benefit herself, not others around her. This philosophy upsets the men in the novel. They are usually the ones who benefit from their actions, while women’s actions also benefit them.

Hansson and Norberg also point out that the men in the novel are allowed to be emotional because they have nothing to lose from it:

“The male characters in Lady Audley’s Secret can indulge in a greater range of emotional behavior without loss of position. There is an implicit relation between emotional expression and social power, so that male characters, and in particular those of the upper class, retain the reader’s sympathies, regardless of their aggressive or hostile behavior” (446).

We see that Lucy must remain stoic about her actions because she is fighting to keep her power. If she shows any tears or trembles in her voice she will be giving Robert the upper hand, something she is smart enough not to give away. Throughout Lady Audley’s Secret we see men embrace feminine-like emotions, which garner sympathy from the reader. This sympathy risks turning the reader against Lucy, as it always implies that she is hurting men like Robert. Her selfish actions confirm to the male characters that she is mad, because a “normal” woman would never act in a way that hurt them.

Along with this, we must reflect on why Lucy felt the need to keep her anger against society a secret. Hansson and Norberg discuss this as they explain that women are trapped, “in a double bind, since they are socially prohibited from expressing their anger in terms of combat, at the same time as their failure to give open expression to their feelings is what makes their anger secretive and threatening” (447). Victorian women, therefore, are forced to keep most of their emotions to themselves. Lucy’s madness then is directly linked to the fact that she does not keep her anger a secret. She outwardly admits to feeling abandoned by George Talboys, disliking her own son, and using Michael Audley to advance her rank in society. We perhaps see her anger come out the most when she attempts to burn Luke’s hotel to stop Robert from exposing her. This act of violence is Lucy’s way of protecting herself. One could argue she feels a right to do this because men are trying to take away what she’s earned. Either way, Robert labels Lucy’s outward anger at a woman’s position in society as madness because she is embracing it.

Therefore, Lucy’s outward belief in putting all of her love and devotion into herself shows when a Victorian woman does something to help herself, she is being selfish and that is seen as mad. Women during this time should have only been concerned with how they can serve others. This shows an oppression of women being their own person with their own needs. Braddon is challenging Victorian Literature’s notion that women are meant to be seen and not heard. In Lucy’s rebellion and selfish behavior, she is actually breaking the stigma around a woman’s madness diagnosis. Lucy’s self-reliance shows that women can be emotional on purpose and not just as a biological side effect of their gender.

Works Cited

Braddon, Mary Elizabeth. Lady Audley’s Secret. Digireads.com Publishing, 2020.

Florschuetz, Angela. “Madness as Domestic Defense in Lady Audley’s Secret and Jane Eyre.” Articulate: vol. 4, no. 8, 1999, pp. 65-71.

Hansson, Heidi; Norberg, Cathrine. “Lady Audley’s Secret, Gender, and the Representation of Emotions.” Women’s Writing, vol. 20, no. 4, August 2013, pp. 441-457.

Hatley, Kelsey. “Taking Back the Pen: Sensation, Sanity, and Subversion in Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret.” Digital Commons: Linfield University, Senior Thesis 9, May 2013, pp. 4-67.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Contra: Lady Audley’s murder of her first husband and her abandonment of her child make her quite unsympathetic.

I’m surpised I’d never heard of Mary Elizabeth Braddon until a few days ago. I found my way to her by chance, through a wikipedia rabbit hole that led from gothic fiction to sensation novels, a genre new to me. And now I am on a deep dive into analytical writing on this genre. Hence I am here.

That’s quite a journey.

The ending was a bit too cliché and kitschy for my taste with the good defeating evil and all of them living happily ever after.

This is an amazing book. I wish it was as well known as “Jane Eyre”, “Wuthering Heights” or “Great Expectations”, it certainly deserves it.

Lady Audley’s Secret is a hidden gem in the classical crime and mystery genre. To be honest, I had never heard of it until a few days back when I was browsing through the Penguin English Library collection on the web and stumbled across it.

I want to read every Victorian sensation novel ever now.

I had never heard of this author until she was mentioned in the Victorians group and am thankful to them for bringing her to my attention. I haven’t read this book though so thanks for introducing it to me.

This is a frustrating novel to read, because I am so utterly in sympathy with Lady Audley. Just think: to grow up in poverty, with no means to escape it, then to marry yet more poverty; to have your husband abandon you with no money nor occcupation, to raise your child alone; to recieve no news of your husband and sole support for years, and finally, to resolve to better your station. To then earn your living, and marry very well, only to be abruptly confronted with your first stupid husband’s return. What else *could* one do, but kill him and hide the body?

To me, the best part of the novel was the matching of wits between Lady Audley and the man who intends to bring her to justice.

I heard a Radio 4 adaptation ages ago. Have you heard it? It is a really good adaptation.

Great piece. So often reading classic fiction can end up feeling somehow worthwhile or virtuous rather than pleasurable but Lady Audley’s Secret was pure fun.

Ah, this article made the lineup! Again, lovely work. Lady Audley is a particularly nasty, though complex, villain who needs more attention (from literary analyst circles, that is).

As a Victorian literature enthusiast, I’m disappointed that I had never heard of this book before. It is definitely on my list of must-reads now.

A few years back the Oxford day school on Victorian Literature had Lady Audley’s secret on their reading list along with Dickens and Hardy. I rather liked this novel and found the writer E.M. Braddon’s own personal life just as intriguing. I do recommend this book for those who like a good Victorian heroine intrigue as was ‘The Woman in White.

As a mystery novel, it failed to provide a stimulating, thrilling secret for the reader to contemplate. But as a drama, it soared.

Lady Audley was portrayed perfectly; I would loved to see a photo of her.

I have no idea why this book isn’t as popular as other novels of the time. Perhaps because theres no “good woman” who is the protagonist.

While this was a well-written story, I found that it wasn’t an overly compelling read. There was nothing too mysterious or scandalous in any of the revelations or secrets.

I actually quite enjoyed this BUT the biggest thing that bothered me about this novel is how it is structured to make Robert the hero detective man of this story, and Lady Audley as the villain. But I find it to be 100% flipped around since this entire thing wouldn’t have happened if Robert hadn’t brought his friend to the Audley Court and everyone would have been able to just live their lives happily. Also Sir Michael Audley did nothing wrong, poor dude.

In many ways I appreciated how over-the-top and melodramatic this is but I couldn’t take three hundred pages of it in the end.

I love the detailed descriptions of each character in this classic.

This was such a great, easy and creative book. i was hooked after the first page.

It’s the Gone Girl of the Victorian era – popular fiction at its very, very best.

This book is a perfect example of its genre. Unfortunately that made for a predictable read.

Lady Audley is badass. She isn’t scared of a little violence or defaming a family member. Great novel. Classic.

This was so well-written! I couldn’t help myself getting immersed into the life of Lady Audley with such helpful quotes and pictures.

Lady Audley is not the heroine of this book; it is Robert Audley, and he is quite annoying, I couldn’t get attached to him, or appreciate him.

I had no idea how much I was going to love this book when I started reading it. Strangely, it is not discussed as much as it should be. thanks for the read.

This is no great mystery but it is a jolly good read!

Great sensation novel that deals with issues like bigamy, madness and deception. Lovely analysis.

I think the story could have been told in half as many pages but that’s the Victorians for you!

There is only so much dramatic irony readers can take.

Welcome to The Artifice. Great first article! <3

It’s very melodramatic and twisty.

Great victorian literature!

I have never heard or seen this version before but it is very interesting how it touches on some basics of life events. We all go through heartache and some emotional stress. So to some points, I can relate and to others, I am a little distraught. Yet very interesting still

Oh gosh, thank you so much. I’ve been on the hunt for a good novel, but find some books so repetitive. I’ll keep you posted. Cheers!

This book is assigned for a literature class I’m taking next semester. Thank you for sharing this nice introduction!