Preservation, Insight and Growth Through Literary Modernizations

Stories are resilient things. It is truly incredible how just a few groupings of words uttered years ago can manage to withstand the test of time. Sometimes, stories travel with their original covers; their main settings and characters and plotlines remain intact. Though more commonly in today’s world, one will find stories that have been shaped by the years they have endured.

Revitalizations of Shakespeare’s tragedies, reimaginings of Sherlock’s wit or Cinderella’s hope. Readers have a hard time letting go of the tales that resonate with them, so they’ve found ways to carry them as they go. They’ve learned how to tell old tales in modern words that keep their origins alive, and give them new life. With this new life, modernizations play a key role in how some of society’s most cherished stories are understood, preserved and reshaped throughout the ages.

Modernization and Translation

First and foremost, modernizations are key to helping new waves of readers understand a story, despite its dated nuances. Most anybody who has read older literature in high school understands the frustration of trying to decipher it page by page. While beautiful and carefully crafted, an aged text can often feel like it’s written in another language. And in a way, it is. Words are human, they grow and change just like any person. If one drops a century old play in a young readers lap and asks for the meaning, the reader will most likely panic. Then they’ll probably spend the majority of their time trying to explain what the lines say, not what they mean.

Understanding the structure and cadence of an older language takes time. And while anything worth doing takes time– especially getting to the core of a challenging text –not every reader is willing to exhibit such dedication. Modernizations bridge this gap. They give readers an insight into an older text without some of original story’s the contextual challenges.

Shakespeare is a shining example of modernizations’ ability to connect new readers with old texts. It’s difficult to picture where modern literature would be without Shakespeare’s contributions. Some of the most relatable characters known to story, themes and tropes that live on in every other plot, a world of new words: these are just a few of the gifts that the Bard of Avon wrote to life centuries ago. And there will always be those who appreciate these gifts as they are. But for those who are unable or unwilling to go to such lengths, modernizations build a window for the masses to experience Shakespeare’s work.

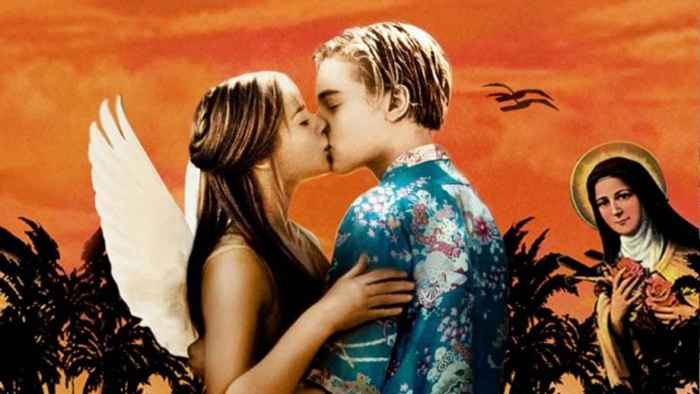

After all, Shakespeare’s plays and poems were meant for the masses. Even the poorest citizen might have been able to find some respite from life’s harsheties upon entering the Globe Theater. Modernizations create a similar sense of accessibility for current day readers to enter Shakespeare’s foundational works, no matter how far fetched the interpretation may seem.

For many who have struggled to understand the classic Romeo and Juliet, the 1996 film William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet is just one visual depiction of this play’s tragic, emotional undertones. While some may balk at the current day, California setting (or the fact that Romeo wears a Hawaiian shirt for a good chunk of the movie), this modernisation’s roots still lead down to Shakespeare’s original words. 1 Nearly every line of dialogue is plucked from the play itself, but it is this film’s unique interpreation of those lines that helps younger ears understand them. Depicting the Montague-Cappulet rivalry as opposing gangs, putting the face of a young Leonardo DeCaprio to Romeo: these are relateable characters set in a recognizable world, these are what make the story real to the viewer. 2 It helps viewers feel as though Shakespeare’s work is not a locked door, but something waiting behind a frosted window, ready to be seen when looked at the right way.

Keeping a Character, and Their Insight, Alive

In turn with practical translation, another shred of why society modernizes tales might be fueled by something more personal: sentimentality. A book is a journey, one that the reader makes alongside each character. And letting go of that connection is hard. After all, a character is like a friend etched in ink. Readers learn from them, connect with them. Sometimes a character who only exists on the page can ask someone to completely reconsider who they are. So society tells their stories again, and again. And again. They help these characters live on within them, every time their name passes their lips, every time their adventures are retold. But sometimes, readers do more than that. Sometimes when the last page is turned, questions remain. What would this character think of today’s world? What would they do in a certain situation? These questions are a spark. Modernizations often follow as a way to seek the answers.

One prime example of this idea is Sherlock Holmes. It’s nearly instinct to picture his iconic deerstalker cap and pipe at any mention of a mystery. One could even claim that Holmes has been the embodiment of this literary genre ever since Sir Arthur Conan Doyle brought him to life in 1887. 3 While Holmes has cemented himself into the world of story due to his daring escapades and characteristic cunning, there is something more that has kept his character alive. His keen insight, his ability to tackle the most impossible seeming situations. 4 In seeing Holmes’ adventures by his eyes, the reader– for a brief moment –is given the chance to be a hero. Through Holmes, a reader can see what most cannot, do what most would never dare to do. A character like this does not fade easily from a reader’s heart. As a result, many have tried to recreate this man’s insight as a way of examining the world beyond Holmes’ pages.

This blue planet is brimming with gray situations that make one yearn for the fictional schemes of Professor Moriarty. However, amid today’s many difficult questions, Holmes serves as an impartial lens. Who better is there to make sense of things than the one sleuth who can connect the dots most don’t even see?

Some of today’s renditions hold more closely to Holmes’ original adventures, such as the British Drama “Sherlock,” starring Benedict Cumberbatch. Despite the 21st century timeline and a few contemporary tweaks, this depiction of Holmes is an escape into what many imagine this character’s world to be. It is a snapshot of rainy intrigue nestled in the darkest corners of London. 5 This is a familiar tale viewers can easily jump into when the problems of their world feel too grand, too scary, too unsolvable.

Other renditions have their roots in Doyle’s stories, but take greater liberties with how Holmes and his escapades are represented. Brittany Cavallaro’s novel A Study in Charlotte ponders the sort of quandaries that might befall Holmes’ very distant granddaughter. With its’ modern day boarding school setting, Cavallaro’s world is a far cry from the traditional Doyle interpretation. But this modernism also depicts how a Holmes would navigate many aspects of the reader’s world, topics spanning from petty school drama to greater hurdles like addiction. 6 By reimagining Holmes in this way, the image of his character gains another dimension, another thread in the fabric of modern story. Like every modernization, Cavallaro’s image of this century old hero keeps his original spark burning. At the same time, this spark also lights the way for other storytellers– those who have taken up their own deerstalker cap and tried to unravel a new chapter of mysteries.

Old Roots and Growing Branches

While modernizing stories plays a key role in their preservation, one final aspect of its importance lies in how it encourages growth. As was previously mentioned, a connection forms between reader and book from the very first page. Stories leave a mark, even when a reader sets the book down. It could be the grandest, most morally complex tome known to man. It could also be a favorite childhood tale. The word count and complexity aren’t what matter most when it comes to loving a story. It’s the heart. Characters that readers see themselves in, triumphs and braveries and acts of kindness they wish for in their own world. These are the pieces of a story that a reader carries within them. But sometimes when a story is carried for so long, that story begins to grow with the reader. And more often than not, this growth gives way to a literary modernization.

Classic heroes, familiar arcs, aged tropes: they all stand like steady pillars. These are foundations of story that authors, directors and playwrights often turn to when weaving their own tales. But as times and people change, many have taken up the mantle of reshaping certain stories and pillars to fit their world. The spark of a new tale is a bright thing, glowing with the need to be expanded and shared. Finding the right way to communicate these messages can be difficult, yet sometimes the answers lie in a story that has already been written, and read. A story that perhaps has more room to grow, more buds waiting to bloom.

Modernizations can provide a way for someone to venture the great heights of building a story with the steady guide of a familiar plot. Some retellings choose to keep a tale’s original themes intact, opting for structural or contextual changes. Others decide to tell an old story in new words-with new themes, messages and commentary to match. No matter the unique path each retelling forges, they all end up leading to a very similar destination. They all strive to give a classic story more meaning than ever existed within its original pages.

There is a comforting nostalgia to fairy tales. Fantasy and romance and happy endings are hard to dislike. But sometimes, it’s difficult to see how some of these joys might be achieved in today’s world. It can also be difficult to agree with how society’s favorite characters found them in the first place. A desire to overcome these difficulties has lead to an ever expanding library of modernizations centered entirely around fairy tales.

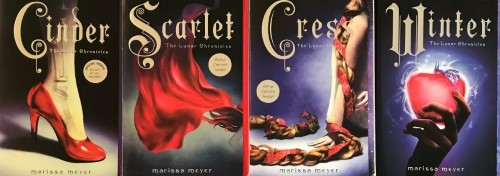

After growing up reading about Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood, readers never seem to stop searching for an echo of these tales in the real world. These stories have taught readers to root for true love against all odds, to believe in heroes who will save the day before the wolves pounce. Though some go a step beyond, searching for a way to give these stories new endings, and new opportunities. One might say it’s a step too far to make Cinderella a cyborg in a futuristic, plague-ridden world. But for Marissa Meyer in The Lunar Chronicles, this was her way of giving Cinderella a happy ending in a world of her own making.

Despite a steady tether to the aged fable, Meyer’s rendition paints a different side of Cinderella: a side where this beloved princess is more hero than damsel. And in this way, Meyer paves a new way for readers to connect with this character. In Meyer’s eyes, Cinderella doesn’t need a fairy-godmother to lift her from the ashes. She finds her own path. She fights for her place in a world that despises her for the wire and metal that run alongside her bones.

In both this modernization and the original, Cinderella holds tightly to hope, to what she wants despite the dark circumstances around her. But each rendition shows a different route of reaching this hope, of how a reader might seek this light in their own life as well. Meyer is just one of many authors who have decided to rewrite Cinderella’s journey, but she and these other writers share one very important thing. They all decided to use a well loved story as a once upon a time, a springboard, a second chance for their own insights. They all decided that a very old story may still have something new to share.

Modernizations: More Harm Than Good?

Some may argue that modernizations go too far, change too much. Change is hard, especially when it comes to a story with deep roots in people’s lives. Besides, how could any retelling ever live up to the great lofts of the original? This is the gauntlet every modernization is thrown to, a never ending battle between a comforting past and unfamiliar future.

Strangely enough, love is often the catalyst of this battle. Once a reader commits a story to heart, it isn’t easy to watch that story be reshaped. It is almost like a loss, to watch something familiar become unknown, something that must be reread and re-understood. The once comforting echoes of a loved tale might feel like a trick or deceit when draped in the redesigned folds of a modernisation. Resent is simply instinct upon realizing that a dearly held story lacks some of the critical details or notes that define it.

But reading isn’t always easy. Despite being a literal open book in some cases, stories ask for commitment and patience and dedication. Sometimes the hallmark details a reader desperately wishes for take time to uncover, skill to reassemble. Sometimes those pieces aren’t there at all. Despite old roots, one of the first steps to appreciating a modernisation is simply accepting it for what it is, a modernization. An orchestra of wisps and whispers that resonate with the reader, and new chimes that may not. New chimes that still have meaning, something to say, even if they do not say what the reader expects.

Not every Cinderella will be the adored princess of childhood. Not every Sherlock will be a genius hero. However, just because a modernisation might not carry it’s original tune to the exact doesn’t mean its melody should be renounced. It is not meant to paint a classic piece in slightly altered hues. After all, that story has already been told. A modernisation is a work of its own. An ode to an original with new light to shed and new paths to explore.

In a way, modernizations are simply another chapter.

They are a branch off an ancient trunk, an ember from a long burning flame. And this ember can do some incredible things. It can spark something new in an author who, far down the road, is looking for a way to bring their own vision to life. One who is searching for a means to give their own ideas and perspectives a voice. Every time a retelling is held in someone’s hands, the original story echoes from within. Only this time, it has a new rhythm and melody and reflection, waiting to be found. Waiting to be heard. Every modernisation is an opportunity for an old tale to teach again. But these lessons can only be grasped upon pausing, breathing, and giving that modernization a chance.

Why Do Modernizations Inspire Hope?

This world of modernisations, of overlapping stories, is a complex one. It is held together, simultaneously, by a steady grasp on past tales and bright visions for the future. And it is constantly changing too, especially in today’s digital age. There are always new things to learn and keep up with and see. But even as new stories are spun every day, the old ones provide a constant within this constant change. In a way, it is the very nature of today’s modern culture– to move forward and adapt –that fuels society’s need to modernize and adapt older stories as well.

When a story resurfaces again and again, it becomes more than a time honored tale. It becomes a light, a hope, that even as this world keeps moving, some things will never be left behind. When it comes down to it, the very society that fuels such unyielding change also has a quiet desire to stall. Or at the very least, help some things– some stories –bloom up through each new layer of what society has built.

When Sherlock Holmes died (for a short time) upon the release of “The Final Problem” in 1891, people simply wouldn’t have it. While Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was more than ready to set the quill down for this hero, he wasn’t expecting the backlash this act would create. The magazine that published Holmes’ escapades, The Strand, lost around 20,000 subscribers when Holmes’ took his fatal tumble off a cliff. 7 Doyle himself received betrayed notes from fans who had been following Holmes for years, who mourned his death as if Holmes were a real person. 8 To Doyle’s readers, Holmes was real. With every adventure Holmes grew beyond his original ink, grew into the hearts of readers that refused to let him go. Every Holmes retelling, every modernisation since, is an ripple of this determination. A determination that pushed Doyle to take up his quill again, and pushed many others to do the same in rewriting Holmes’ tales.

Modernisations are sought because they make the very same statement that Holmes’ followers made over a century ago: even the smallest story, the most ordinary reader can refuse the great tides of time. Each retelling gives a reader hope that even a world of unending impermanence is no match for a simple sleuth, a fairy tale princess, a star crossed couple. Whenever a certain clever crime solver makes another appearance, whether on the screen or on the page, Holmes continues to survive. In a way, seeing stories, beloved characters, surpass the brutal weathering of time allows one to believe that such survival is possible. That something familiar can always be found in an unfamiliar world.

New Chapters and New Sparks

At the end of the day, this world tells stories to keep their flame glowing. After all, a story only lives for as long as it’s told. This is what makes some tales a mere flicker in this world, while others manage to burn for countless lifetimes. The ones that burn the longest often maintain their original form, more or less. Years of recitation certainly take their toll, but the library’s copy of Hamlet or The Odyssey is likely very similar to the one that was read fifty years ago (and fifty years before that).

Even if a story remains unchanged, however, the way that it’s read inevitably shifts with the society reading it. The human morals, meanings, themes: these are the pulse of a story. These are the pieces that determine how long the flame of a tale will burn. And every age of readers will see this flame a little differently. With their roots in the original tale, modernizations create new ways for new eras to see by this glow.

A story is a living, breathing thing. At its core, it is deeply human. This is why humanity is so dependent on tales. They are a part of each reader, a snapshot of the world taken through someone else’s eyes. And they follow, too. They weave themselves into the way society understands things, into the stories one sees and the stories one lives. Every now and then, one might find a way of reshelving a very old tale into the next chapter of society. And in this reshelving, one might find a way of helping to preserve, understand and rebuild an old tale too. One might find a way to give this tale a new once upon a time.

It is a powerful thing, to retell a story. It requires responsibility and compassion to take someone else’s characters into one’s hands. But it is also a beautiful thing, to feed the old flame that lies within paper thin pages. To help a story remain in the hearts of readers, to find new insight in old words, to coax a bloom off an old tale weathered by years of being shared. Again and again.

Works Cited

- Luhrmann, Baz, director. William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet. Performances by Leonardo DiCaprio, Claire Danes, Paul Rudd, 20th Century Fox, 1996. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Kasius, Jennifer. Sherlock Holmes: The Essential Mysteries in One Sitting. Philadelphia, Running Press, 2013. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Gatiss, Mark and Steven Moffat, creators. Sherlock. Hartswood Films BBC Wales WGBH, 2010. ↩

- Cavallaro, Brittany. A Study in Charlotte. New York, Katherine Tegan Books, 2016. ↩

- Armstrong, Jennifer Keishin. “How Sherlock Holmes Changed the World.” BBC, 6 Jan. 2016, www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160106-how-sherlock-holmes-changed-the-world. Accessed 5 July 2022. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I really enjoyed Cavallaro’s Charlotte Holmes novels. I thought it was an intriguing idea to explore the legacy of Sherlock Holmes (as if he were real and someone’s ancestor).

Great article. Just popped by to recommend Neil Gaiman’s “Snow, Glass, Apples” to anyone who hasn’t discovered it – a 180 degree retelling of Snow White from the point of view of the “evil” stepmother.

Just last weekend I went with my children here in Germany to a local rendering of a Grimm tale called ‘Allerleirauh’ which is to do with a princess whose mother died. Her father, the king, searched far and wide for a new wife as beautiful etc but could not find one and in the end decided to marry his daughter. The story takes off from there, and yes, the lovely daughter, assisted by kind wild animals along the way, gets to marry her fairytale prince. Watching this play, presented to young children, I as an adult felt a visceral shock at the incest theme and wondered how the children were taking it. Asking them afterwards they just said of course it was wrong to want to marry your dad but they were otherwise undisturbed and loved the key part of the dresses woven from moonlight, starshine and sunbeams.

I think children/people the world over recognize this in stories: What happens in the cause and effect world and what happens in the “other” world.

Some of the Grimm’s Tales are stories that had migrated to the German nations with Huegenot refugees and probably fused with local tales.

Thanks to ALL the tellers of tales! Knowingly, or unknowingly, you have given us stories and visions that have made our lives richer.

Andrew lang’s fairy tales include tales of African origin.

People have been adapting things in oddball ways for ages. They took Romeo and Juliet and made it a musical about gangs. They took The Odyssey and turned it into a bloke walking about Dublin. They apparently made Hamlet into a cartoon about African wildlife I very much doubt is a documentary.

Good luck to them all. Art lives by adaptation and reinvention.

As a diehard Austen fan who doesn’t read fan fiction (sequels, prequels an the like) but who does watch film and television adaptations, I was very impressed by The Lizzie Bennet Diaries. It’s smart, sassy, engaging and does a good job of situating Austen in today. It’s NOT Austen but it’s great fun … and catches the essence of Austen’s characters. I highly recommend it to people who read this article.

This sound brilliant.

Since stories never end, but just pause at the beginning of another story, I’d like to see a series called “Act Six” – writers imagining what happened after the characters walked off stage. There are three very strange marriages about to get under way at the end of “Twelfth Night”, for instance – Olivia has tied herself to a total stranger, Viola will always be aware that she’s the second choice, and as for Maria – a few mornings waking up beside that snoring, farting hulk and she’s going to wish she’d never written that bloody letter!

One fifteenth-century reader of Chaucer so enjoyed the Canterbury Tales that s/he wrote another ‘episode’ (the so-called ‘Canterbury Interlude’) describing the arrival of the pilgrims in Canterbury, their visit to Becket’s shrine and a night in the pub!

There are lots of other ‘additions’ to the Chaucer corpus.

One re-make that was at least as good as the original is the 1964 version of The Killers by Don Siegel starring Lee Marvin and John Cassavetes. I really rate this and the 1946 Siodmark version which starred Burt Lancaster too.

What are some remakes you all like?

The Crazies remake was a pretty decent effort. I very much doubt that Romero would dare to criticise it, considering how slapdash the original was.

The 2005 King Kong is a good remake, great use of CGI technology.

The ultimate labour of love.

Have you seen the documentary where Jackson & co re-create the long lost “Spider Pit” sequence from the original? Now that’s a labour of love.

The Fly, The Thing, both brilliant remakes. The Maltese Falcon, another remake. I like the 1960 Magnificent Seven. It can be done well

Both examples of films having subtext added during the remake process rather than the usual tendency to strip it away

What about Scorcese’s Oscar-winning THE DEPARTED, a remake of Andrew Lau’s excellent INFERNAL AFFAIRS (including the dead protagonist’s head being repeatedly slammed in elevator doors at the end)? I had no idea until I took up watching Asian films as a hobby. This revelation fundamentally changed my views on film making.

Infernal Affairs is long form cinema. The Departed is the abridged version.

How did it fundamentally change your views on film making, lots of these films are remade,

Oceans eleven remake was fresh and clever. But they had to make the sequels.

Gladiator was simulataneously a sort-of remake of Spartacus and The Fall of the Roman Empire.

With a bit of Mad Max…

Sherlock is good, watchable television but it’s nothing special and frequently predictable.

Jeremy Brett hands down always be the best Sherlock Holmes. His interpretations of Sherlock Holmes was 100% true to the books.

The best Holmes: Douglas Wilmer.

I thought I was the only one who thought Douglas Wilmer was the best ever. Jeremy Brett gave himself over to the maniacal, obsessive aspects of the character, while Wilmer just showed glimpses and hints which were much more effective, I thought. Less of a one-note performance.

That’s partially the fault of adaptation; we all know Moriarty from the original ACD stories, the various movies, radio adaptations, and television adaptations. Is SH culturally significant? Yes. Is SH predictable at this point?

Fascinating article, very well written. I’d like to have seen a paragraph about the actual work of translating, too, and how that influenced the new versions.

Go on – rewrite the Bible, the complete works of Shakespeare, everything Tennyson ever wrote – in fact everything that is out of copyright, why don’t you?

They all need a make over and an update to be ‘relevant’ for our times.

I’ve recently been reading Andrew Lang’s ’12 Fairy books’. Whilst the narratives are excellent, there is no characterisation at all, and the stories end summarily and unsatisfyingly in 3 pages. If that.

I’ve longed for them to be made fuller and more complex. There is something about the way fairytales capture the crazy inexpicability and abrupt changes of life that needs to be told at more length.

I wonder if you have come across some interesting fairy tales in Africa? I’ve heard a couple of truly brilliant from this continent in that they are “non-linear” (?) in the telling!

Excellent article. As a storyteller I find it’s all about pace, peoples eyes start to glaze over if I get stuck on description. And everything is best in primary colours painted boldly. Familiar characters are short hand and again mean that the action can run along at speed.

Personally I find very convincing the idea that the psychology of a classic story lies not in the individual characters but that each character and element in the story represents a different aspect of the human psyche or emotional experience – lost in dark woods, battling the monster, the divided self. So despite there being no interior lives, the stories as a whole contain psychological truth. I think that’s why we recognise them and why they resonate.

Every time some publisher or producer wants to make money out of Shakespeare, they claim that whatever venture they are undertaking will ‘bring Shakespeare alive for contemporary audiences/readers/children…’ It won’t. Cover versions, ‘contemporary reimaginings’ (did anyone really think about that phrase before letting it roam about in public without constant adult supervision?) and all other kinds of derivative works always lack one thing: Shakespeare’s language. Ever since Charles and Mary Lamb published their own prose re-telling of Shakespeare 200 years ago, the closest connection to what Shakespeare wrote has been the name of the story. It is Shakespeare’s language that makes his works either compelling or impenetrable for people.

Being told the plot of Macbeth isn’t the same as being introduced to Shakespeare.

I couldn’t agree more.

The idea that contemporary authors cannot create genuinely new work inspired by the canon is very narrow, and if you’ll forgive me, probably held by people who are not themselves writers.

His genius is in the language and dramaturgy.

There’s an old saying that the past is another country, and I think it really holds true for modernizations of older works. A lot won’t necessarily be understood by modern audiences, both language and cultural references. Shakespeare often comes with a guide in classrooms for a reason, after all. In some ways, and for certain types of retellings, I feel like you can see the modernization process like one of translation – translating an old piece for a modern audience.

Not all retellings are an attempt to do that, of course. Some are just playing in the space that a classic or fairytale provides. But many seem more an attempt of translation, to make a piece understandable to a modern audience without extensive study of the original time period.

Great article! I think modernisations and adaptations are so important, not only to draw in new waves of readers who might be indimidated/gatekept by the original material, but also to provide a chance to address issues in the source material that perhaps may not have been seen as issues at the time it was written, but are definitely perceived that way now. Not talking about entirely rewriting or excising out problematic elements in fiction, but modernisations and adaptations can definitely provide a space within which to critique those elements while still clearly showing respect and love towards the original source material.

I think re-makes are a bit like cover versions of classic songs – they shouldn’t really be attempted unless you can do something original with them and put a new spin on the original.

America had the best Sherlock for years. Only difference being that they called him “House”, not “Holmes”.

Very well written, I have to admit I do have a preference for some of the revivals of Hamlet versus a more traditional rendition.

People have been adapting stories in new settings, and with new words, for ages.

I love the idea of stripping down of the classic stories.

Poetry has a way of doing that – with fresh language.

I’m a big fan of the literary webseries genre, YouTube vlog-style adaptations of classics from Jane Austen to Shakespeare to the Brothers Grimm. They’re excellent.

Great job! I loved all your points, and your comparisons, such as Shakespeare’s work existing behind frosted windows rather than locked doors. And as a lover of fairytales (I’m still a Oncer), thank you for bringing those tales into your article.

I’m a lover of literature, but an avid non-lover of Shakespeare. I have so much respect for his craft but I have always said “I hate reading his work.” This take makes me want to re-visit my thought precession regarding Shakespeare’s work. This stuff HAS to be preserved at all costs. It is so unique and you brought this to my attention through your own writing. Word up.

Illuminating and compelling point of view regarding the purpose of modernizing classic literature and tales: to (re)ground hope through familiar characters even in different retellings and versions. In my instance, Ever After, the Cinderella retelling which features Drew Barrymore as Cinderella, continues to resonate with me from the first time I viewed this film in the early ’90s to now.

Excellent overview of enduring stories that have become archetypal! Also loved the question of whether modernisations cause more harm than good in their treatment of a beloved narrative – can they destroy the original message? But I guess, all in the name of continuing the existence of these timeless tales…