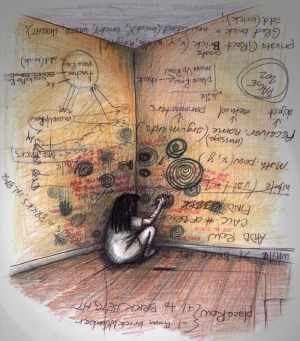

Mental Illness in YA: Rehabilitating Sick-Lit

When one thinks of narratives about mental illness, the characters described are no longer limited to the subversive and villainous. Instead, mental illness narratives are taking on a new role: one of healing, growth and acceptance. Twenty percent of teens worldwide are affected by a mental illness; it is clear that this is an important topic to address (WHO). However, it has also recently brought certain questions into the forefront of discussions regarding how these stories are written. Dubbed “sick-lit” in news outlets such as The Daily Mail and The Globe and Mail, there is an aura of concern around an otherwise excellent genre of young adult fiction. Concerned parents and journalists have argued that some stories involving mental illness prompt young readers to harm themselves or become depressed. In light of recent criticism, some have questioned whether it is possible for a sick-lit narrative to maintain a good balance between realistic representation and sensationalizing otherwise serious topics. The notion of rehabilitation in sick-lit may have a history of being romanticized, but in recent years a resurgence of new stories seem to be doing just the opposite. Although it is the protagonists who are affected by a serious illness, is sick-lit itself the one being rehabilitated? While there are a number of recent YA novels that normalize mental illness, for the sake of deeper clarity, this article will focus on a single text to examine a new way of narrating mental illness stories.

What is Sick-Lit?

Sick-lit is not new. In the Victorian Era, it focused largely on protagonists with consumption. As a sub-genre in the 1980’s, it predominantly featured young, sickly white girls who found their salvation through handsome love interests and wore makeup so that they could maintain the appearance of wellness until they were either cured or died tragically. Narratives of rehabilitation in the 1980’s also focused on a protagonist’s transition from being different to conforming to cultural norms. In her article Nothing Feels as Real: Teen Sick-Lit, Sadness, and the Condition of Adolescence, Julie Passanante Elman writes that “Teen sick-lit materialized…offering a good cry as a form of rehabilitative treatment for still-malleable teen proto-citizens,” suggesting that sick-lit narratives served as a way to instruct their young readers on how to “get over” an illness rather than finding acceptance from within. This outlook on illness, is problematic.

The “Problem” Narrative

Where earlier stories are maligned for simplifying narratives by making illness a “problem” to overcome, there is another trend that creates a more realistic portrayal of characters who are affected by an illness. Narratives focusing on treatment as a normal part of life and therapists who are depicted as positive helpers on the protagonists’ journey are the new norm.

In The Rest of Us Just Live Here, when Mikey talks about his therapist, he says “This should be the place where I make fun of [Dr. Luther], where I put her in my past as a goofy hippie chick; a lonely lady, soft as a wild herb, looking at us poor, wounded kids with the eyes of a fawn. Except, she wasn’t” (179). Not only do readers get a sense that Dr. Luther is respected by Mikey, but also it is clear that going to therapy is not at the centre of Mikey’s struggle. Certainly it is a part of his life throughout the story, but the fact that visiting his therapist is a normal occurrence suggests to readers that having OCD isn’t something that Mikey can or will “get over.”

In an interview for The Walrus, Teresa Toten talks about her own experience writing about OCD in her novel The Hero of Room 13B. She says, “For most sufferers of mental illness, my personal view is that you have to learn to make friends with it and accept it, because it’s most likely never going to go away completely. It’s something that is a part of you.” What this suggests is that the trend in sick-lit is shifting towards portraying characters that love themselves because they are different. Part of the rehabilitation of this genre involves re-defining how readers come to understand the treatment process as a positive, ongoing part of life.

Is Love the Best Medicine?

If rehabilitating the notion of therapy in literature means de-stigmatizing the ongoing process, there is still the issue of romance within YA books that also deal with mental illness. Some of the criticism from the media has expressed concern over narratives that use romance as a way for characters to experience healing.

In The Daily Mail, Tanith Carey writes that “the genre encourages young girls to believe that the most important thing to worry about when facing serious illness is whether boys still fancy them.” Clearly this is a problematic way to look at illness, but it is also not the only narrative available to young readers.

Towards the conclusion of Ness’ book, Mikey’s best friend and one-time love interest Jarod, attempts to heal Mikey using his godly powers. Critical readers might examine this moment from the view that once again, love has managed to conquer all, including Mikey’s OCD. However, Mikey says, “But you can’t. That’s always been too complex” (301). Even when he is offered the option of being cured, Mikey turns it down. Romance in this fictional world is more like one facet of a supportive network of caring people. Love does not cure Mikey, even though within the world that Ness creates it is certainly possible.

What makes this a good story is not the fact that OCD is addressed at all. Instead, it is the excitement of escaping from otherworldly creatures and coming to terms with heartbreak. By sidestepping the clichéd plot device of healing through romance, Patrick Ness manages to tell a meaningful story that brings the struggles of teens with OCD to light without making it the main event.

What makes these stories enjoyable and meaningful is not because they deal with serious issues, but rather that they couple darker issues with other struggles that many teens have experienced. Rather than romanticizing mental illness, it would appear that the best narratives are rooted in the relatable.

Truth is Stranger than Fiction

When considering what a relatable narrative about mental illness might look like, it is imperative to consider who is allowed to write these stories? What makes the rehabilitation of sick-lit complicated is the idea that if one writes about mental illness in the wrong way, it might romanticize the notion of having that illness. And yet, if writers suppress narratives that discuss it, they isolate those who are affected by mental illness.

Sarah Jae-Jones argues that, “The only way to mitigate problematic views of mental illness is to give voice to the character with mental illness” (Disability in Kidlit). Although this is not a new sentiment, in recent years, the voice given to characters with mental illness is borne out of personal experience. Perhaps part of the re-imagining, or “rehabilitation” of these sick-lit narratives means writing from a place of emotional honesty? While it is certainly not a prerequisite for writing narratives involving mental illness, authors such as John Corey Whaley and Patrick Ness have been open about their own experiences with mental illness that inspired them to write about it.

In an interview for Entertainment, Patrick Ness said that, “…I remember myself being consumed with [anxiety]. What’s going to happen? What am I going to do next? It manifests itself in different ways, and for me it manifested itself as really quite bad OCD. Like Mikey, I worked in a restaurant, and like Mikey, there was a time when I would wash my hands so often that they would bleed because I washed all of the oil out of them… . I want to write about this in a true way, where it’s not an issue with a capital ‘I,’ but it’s what this guy is going through.” Considering that Mikey’s OCD takes on a similar form in The Rest of Us Just Live Here, it is easy to see how the authenticity of Mikey’s voice has been inspired by Ness’ own experiences. Perhaps in part the re-imagining, or “rehabilitation” of these sick-lit narratives means writing from a place of emotional honesty?

The New Fictional Reality

We are living in a renaissance of understanding for issues such as mental illness. While the effects and realities of living with mental illnesses are real, it is clear that to dispel stigmatization and romantic notions of mental illness, narratives that successfully rehabilitate the genre subvert popular assumptions.

Rachel Wilson, author of Don’t Touch, writes that, “Because of their proximity to real life, we credit these stories with a special potential to guide or mislead teen readers… to help cause harm,” and perhaps in some ways this is true. In equal measure, narratives that approach serious issues such as mental illness have the potential to inspire readers to have a clearer understanding of real issues, to challenge popular notions of otherwise mystified illnesses and above all, to feel a little bit less alone.

Further Reading: A Rehabilitated Reading List

It’s Kind of a Funny Story, by Ned Vizzini

Lily and Dunkin, by Donna Gephart

The Unlikely Hero of Room 13B, Teresa Toten

Highly Illogical Behaviour, John Corey Whaley

Finding Audrey, Sophie Kinsella

The Nature of Jade, by Deb Caletti

Mosquitoland, David Arnold

Sources

Bell, Amanda. “John Corey Whaley Talks Hightly Illogical Behaviour and the Prevalence of Mental Illness in YA Novels.” MTV. 10. Oct. 2016. Web. 20 July 2016.

Carey, Tanith. “The Sick-Lit Books Aimed at Children: It’s a Disturbing Phenomenon.” The Daily Mail. 3 Jan. 2013. Web. 20 July 2016.

CTV News Staff. “‘Sick-lit’ Popular Among Youth, Raising Alarms in Literary Circles.” CTV News. 22 March. 2013. Web. 20 July 2016.

Elman, Julie Pasanante. “Nothing Feels as Real: Teen Sick-Lit, Sadness, and the Condition of Adolescence.” Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies. May 1, 2012.

Lewis, Megan. “Patrick Ness on Writing Fantastical Fiction for Teens in The Rest of Us Just Live Here.” Entertainment. N.p., 8 Oct. 2015. Web. 20 July 2016.

Ness, Patrick. The Rest of Us Just Live Here. Harper Teen. New York; 2015.

Toten, Teresa. “Teresa Toten: An Interview With the Winner of the Governor General’s Literary Award for Children’s Literature.” The Walrus. 23 Nov. 2013. Web. 20 July 2016.

Townsend, Alex. et al. “Romanticizing Mental Illness.” Disability in KidLit. 23 May 2015. Web. 20 July 2016.

Wilson, Rachel. “Mental Illness in YA is a Minefield: Explore at Will.” Stacked. 2 Dec. 2014. Web. 20 July 2016.

World Health Organization. “10 Facts on Mental Illness.” WHO. Web. 13 Aug 2016.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

One of the great things about younger readers is that most of them read far more widely than adults. Those kids reading JK Rowling are the same ones reading John Green. It’s only when we reach adulthood that most of us become close-minded.

Very true! I wonder if in part many readers tend to read only one genre because bookstores emphasize separate areas for separate genres? Thanks for reading!

That’s something really interesting that I’ve never thought about… that even in the organization of literature we put an emphasis on separate genres and sort of stereotype the people that read them. (Like if you read sci-fi you’re a geek, if you read poetry you’re a sap)

What are stories for if they can’t bring readers face to face with the hard stuff (be it realist or fantasy fiction)? Which is definitely not to equate writing about sickness/ war/ violence etc with good or ‘worthy’ YA literature. The important thing is surely that stories earn the reader’s emotional response through the world and characters they create. What is unforgiveable is to hijack the reader’s compassion – to cynically exploit ‘tough’ subjects to provoke a stock emotional response.

OlaMexa,

You make a good point about narratives that earn the reader’s enjoyment and response through a well crafted narrative. I think that is what is so fascinating about literature in general, that the best narratives are so wrapped up in emotional truths. (Truth is stranger than fiction, right?)

So much of YAL is like fast food, only temporarily filling and lacking any real nutrition. YAL needs all the help it can get as it helps teens trasition to adult-reader levels.

I think that young adult literature is in many ways like any other type of fiction in that it varies, but the best narratives tell us something about ourselves that makes us think a little more critically about the world around us.

When I was a teenager I remember reading ‘Second Star to the Right’ about anorexia and ‘Secrets not Meant to be Kept’ about sexual abuse. Some of the themes addressed in other, less issue driven, books could also be quite dark, difficult or challenging!

I haven’t heard of those books, but I will have to check them out!

As someone who frequently struggles in the face of anxiety and depression, this article is important to me. I want to see more people like myself in the young adult lit that I’m going to read, and recommend to my friends and family.

Having read this article, I’m definitely going to have to check out the books mentioned during it.

Hi Jack,

Thanks for reading my article! I hope that we see lots more YA lit featuring characters who suffer from mental illness too.

I’ve often wondered if OCD, etc. aren’t positive things in certain contexts. For example, I wouldn’t want someone really type B on a bomb squad: “Blue wire? Red wire? Whatever…”

An interesting perspective! Thanks for reading, Tigey!

Mental disorder need body electric flow tune up only…

Piano, car, guitar need tune up also….

Consumption (TB) is now easily diagnosed, as are some mental illnesses. This article made me think about the “normal” category and when a behavior falls into the mental illness side of things, and the effect of environment therein. Just some thoughts. Thanks for the stimulating article.

Hi John,

Thanks for reading!

I do not personally suffer from severe anxiety or depression, but there have been times where I do see a lot of the mixture going on in my, this article is important to me. I want to see more people like myself in this context and see how things like that play out for other people the same way it plays for me. Reading such articles and information on anxiety and depression can be helpful to see how things play out for the young learners.

Having read this article, I’m definitely going to have to check out the books mentioned during it.

Hi Sadafqur,

I’m glad that it could be helpful!

I’m a therapist for teens and a writer of what would probably be considered “sick-lit.” All teens think about suicide at some point—it’s the degree to which they think about it or act on those thoughts that differs. And for kids who have thought about it, or are terminally ill or disabled, giving voice to their thoughts and feelings can help them articulate things they’ve acted out to cope with in the past.

Hi Sager,

It’s great to have the perspective of someone who writes within the genre! I agree wholeheartedly that this is an important voice to have in the YA genre.

Children should not be taken seriously as readers and should not be trusted to think independently about tough subjects.

So ridiculous! If children shouldn’t read about real life things and I’ve read many times comments that children shouldn’t be allowed to read fantasy because escapisim is bad, what should they read?

We should all just be glad that there are young people who still choose to willingly read books and aren’t just glued to the internet.

I think that children are smarter than they are often given credit for. The best fiction is the kind that doesn’t talk down to them; it just tells stories that hold some emotional truth. If stories are our way of explaining the world, then why should children be left out?

It’s hardly a ‘new trend’ to have books for teenagers with difficult subject matter: books such as The Virgin Suicides or The Perks of Being a Wallflower, which are both now well over 10 years old and have major film adaptations. I think it’s brilliant that it the number of stories for teenagers covering all sorts of topics are becoming more popular. I wish I had had some of these books when I was a teenager..

It’s true! As I mentioned in an earlier part of my article, this isn’t a new trend. That’s actually why I was interested in this topic initially, because there has been such an outcry about it even though it’s been around for ages! I do think that the new trend in YA fiction that deals with tough issues has changed the mode in which it tackles these issues, though.

Well-written fiction about real situations in which people cope with courage and humour and that teach you implicitly that everyone is going to die sometime and it’s about how you live what you’ve got, can only be good – they’re not really about the negative but the positive message.

Yea, it’s really all about the way the message is presented, and what’s available today in young adult fiction is subtle, positive and cleverly written.

I agree!

Marvellous article. That’s all I can say.

Thanks so much Mosle! I really appreciate that!

My daughter just turned 7 a few days ago, and is about to finish the Harry Potter series of books, after reading the Diary of a Whimpy Kid series, loads of Jacqauline Wilson’s books, and the Roald Dahl classics last year. I’m wondering if anyone has any suggestions for book series that are engaging and as challenging as what she’s been reading, but are not involved in themes that are too old for her (I realise the HP series is for older readers, but her interest went there, so it was difficult to curb). I’d be so grateful to hear any suggestions! Thank you so kindly.

When I was seven I read The Hobbit and loved it. Also at about your daughters age I enjoyed authors such as Philippa Pearce (Tom’s Midnight Garden is fantastic), Michelle Magorian, Dick King-Smith, Enid Blyton, Michael Mopurgo, C.S. Lewis and classics like What Katy Did, Anne of Green Gables, Little Women, The Secret Garden and The Wolves of Willoughby Chase. Some of these are series, some not, but hopefully all should spin off into other worlds of discovery.

And of course there have been many new great authors since then – I would very much recommend talking to your local friendly librarian or bookshop, and letting your daughter have a good old browse in the children’s section and see what takes her fancy.

If YA authors need to be protecting their readers from “harmful content” then CNN, Fox News, MSNBC and the world at large should have to do the same. Life is tough, bad things happen, and if teens can’t read about it in a way that makes them comfortable they are not going to be able to deal with “what’s out there” when they get there.

Tol,

I thought that the uproar regarding “sick-lit” was pretty strange too.

As a survivor of not just one suicide attempt and with children, it is important to not censor life from them, but introduce life and death and ill health as soon as they can understand and discuss it. Additionally, I would rather do it as a parent talking than with a book, but it is important to do it nonetheless.

Moral,

I agree that discussing these issues with parents is best. Thanks for reading and commenting!

I wonder what people think to some of the Japanese manga my teenage daughter reads.

Some of it is pretty wild!

I’m quite proud that my daughter has spent most of the last few years’ pocket and Xmas and Birthday money on Manga because at least it means she reads sometimes.

Well written and very insightful, it’s interesting to see how some genres have developed as times have changed.

Thanks so much!

When you’re a child, your world-experience is too small for you to understand that not everything happens to everyone.

That’s an interesting point!

As a child, I hated books that dealt with serious issues (we all did – we used to mock the teachers for putting them on the reading lists)… And I did find the fantasy books with the happy endings gave me the strength to cope with any issues I had in my real life.

But that’s a taste thing – another group of kids & teens might’ve loved them.

I’m a huge fan of fantasy novels too and I loved those as a kid. (I love that Patrick Ness’ book incorporates that fantastical element too).

Why are publishers commissioning books about young teens thinking about the best way to kill themselves – when no newspaper or TV story can give details of a suicide or self-harm.

Hmmm…I’m not sure I have an answer to that one, but I do think that these narratives have a place in the YA genre if only because it is a reality for some kids out there.

In terms of how much detail the books go into…that’s interesting, because it varies from book to book.

I really learned a lot from Lauren’s article, Rehabilitating Sick-Lit! What a great article to further the understanding of mental illness in young adult literature. I find this trend to be highly effective in teaching tollerance, empathy and compassion for diversity in such a challenging world today. This is most important when writing for the young, indeed! Thanks for the article!

I’m glad you liked it! Thanks for reading!

Seems “adult” themes in YA fiction are nothing new.

That’s true! I think what is new is the way that they are being approached.

I hate these books. I am sick to death (HA) of all these dead/dying teen books that somehow make you cry without any of the sense of the actual ugliness of cancer and death.

There’s a definite sense of “well at least she lost her virginity first/fell in love”, allowing the reader to sigh with misery/pleasure at the outcome. Kids dying is unbearably ugly and awful and doesn’t allow you to sigh and cry. And most dying kids aren’t thinking about getting laid. Lord knows, I don’t hate gritty subjects for teens. The grittier the better in my opinion. But not this faux-grit.

For an honest book about death, try Patrick Ness’ A Monster Calls. Or Maurice Gleitzman’s holocaust books Once and Then.

I’ll have to check that out! Patrick Ness writes some great stuff.

The problem that we run into when trying to write the “gritty” stuff is that art is subjective. At best, we can show a snapshot of one experience, but not all experiences.

John Green, author of The Fault in our Stars new a teenage cancer sufferer in real life who died, so I very much doubt that his intention was to leave out the “sense of the actual ugliness of cancer and death.”

Well researched article that is topical.

Thanks!

I find this article extremely relatable, having gone through a dark period myself in high school with anxiety and depression. I like the idea of how these types of YAL can shed a new light on how the reader views mental health issues and agree with the way you said “The best narratives are rooted in the relatable”.

Thanks! I’m glad you enjoyed it!

I would be curious to see the correlation between mental illness and gender in YAL. Outside of the “sick-lit encourages teen girls to worry over whether or not they’re dateable despite their mental illness” issue, how often is mental illness seen as a “female” problem vs a “male” problem? And is how we’re portraying it as a “female” problem more or less often helpful? I want data now!

(Good article, btw!)

That’s an interesting observation. I’m glad you enjoyed my article!

In this article, I really agree with Teresa Toten the author of the novel, The Walrus when she talks about her own experience with mental illness. It showed to accept your flaws and to focus on self love. I think there will always be positive and negative feelings on mental illness in novels. This world we live in is full of opinions,choices, and different interpretations on what is said or read. I like the connections in the article or the different ways mental illness can be perceived.

Thanks! I agree that there will always be mixed feelings towards mental-illness in novels.

I maintain the hope that literature gives the underdeveloped adolescent mind the ability to see consequences without the pain and hardship of lived experience. And perhaps it even plants the seeds of empathy within them so that as they come to meet people with diverse backgrounds, they can approach the relationship with a glimmer of humanity. This notion of preventing teenagers from seeing the bad or ugly in the world is unfortunate. For without some perspective how will they come to appreciate the good and the beautiful?

An interesting point! I think that the best narratives have to have some hardship in them.

While suffering through my bout of mental illness in the late 2000s, I read a lot of those “sick-lit” books. It’s kind of like mental illness porn — you see people with the same problems you do, but they’re all swept away when the protagonist meets some handsome young man. And then everything’s okay. Only now, years later, do I realize how damaging this narrative is — and not just for the sick young women, but also the young men who love these women. It’s not healthy for any of them. No one person can be your savior. You’ve got to do that yourself.

It’s true that narratives that make it seem like mental illnesses can be cured by love can be damaging. That’s why I think that it’s always refreshing to see a narrative where being “cured” isn’t the outcome.

Mental illness is a huge part of society today and so talking about it and writing about it helps to start a dialogue and therefore the issues become less taboo and people can get the help they need.

So true!

The thing about YA, especially in dystopian novels, is that teenagers are almost always trying to get away from institutions and all the bad that they do in the world. This sheds bad lighting on those who are actually trying to help and makes readers believe they cannot find help from those that come from institutions. Instead, it becomes up to them to find the solutions to their problems, which is hard to do as it is. Instead, YA novels, as some have done, need to tell readers that finding help is okay and something that should be done. As reading has shown us, we are not alone in what we go through and therefore should not have to deal with these issues on our own.

Thanks for the insightful comment! I absolutely think that is true and so important that people recognize this.

While YAL is a wonderful (and arguably the best) place to start, I think the rehabilitation needs to be extended into other genres to truly have an effect on society. In the same way that normalizing non-hetero characters depends on decentralizing their sexuality, attributing mental illness as one of many traits would reach a wider audience while comforting those who relate. For example, while I’m not ashamed of my bipolar disorder, it does not encapsulate who I am, and I would love to see a protagonist in the same situation.

You make a good point!

I can’t say I’ve read a huge amount of books featuring mental illnesses, but one that comes to mind is A Crooked Kind of Perfect by Linda Urban. The main character’s dad has something that, if it were named, would be something like agoraphobia or OCD. But it never is named. It’s not hyper-categorized, not mentioned on every other page. We just see Zoe’s dad as she sees him: a sweet, attentive, loving father who tends to freak out when he goes somewhere he hasn’t been a dozen times before. Mental illness is there, but there’s more to the story. And I like that.

That sounds like a good book!

Representing mental illness in narratives gives it more visibility, which will help those who struggle with it to feel less alone. Unfortunately, mental illness is often illustrated as an affliction only to be overcome by romantic love. This innately false message breeds a culture of perceiving mental illness as a personality trait, rather than as a disease.

That’s true, and I hope that the trend in these narratives is changing 🙂

The fact that mental illness is presently being given more representation in the ‘mainstream’ literature, is something noteworthy. But, like what was suggested in an earlier comment, perhaps a more ‘proper’ way to represent it is to frame it as it actually is: one aspect of a person’s whole, not a defining factor; a health issue, not a flaw in one’s personality.

I would agree with that. It’s kind of similar to not making the whole narrative about mental illness–it’s just one part of a person’s story.

I’ve read an array of literature that represents characters with mental illness. Some, such as the semi-autobiographical novel, “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden”, represent it in an honest manner. The protagonist, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, recovered through years of therapy while institutionalized.

Another that I read, “Willow”, did not do such a splendid job. The protagonist recovered from depression and self-injury through romantic love, which seems to be a common occurrence in modern literature. I found it so bothersome that the book left me feeling sickly.

However, the increased amount of representation is beneficial.

The first book that you mentioned sounds interesting. I do think that the increased representation is better, although I still think that the best narratives are the ones that take a fresh perspective!

YAL is my favorite genre of lit and I found this book last year that became one of my favorite books about mental illness; it’s called “All The Bright Places” by Jenniver Niven. It’s about two depressed teenagers who fall in love all while trying to repair their self-diagnosed brokenness.

When I first read it I was so angry at how it ended (I won’t give away too much but my reading experience ended in tears – I threw it against a wall and swore off reading for two whole minutes). Then I went back and thought about the last chapter and I realized that it was just so truthful. A lot of YA novels, especially those about mental illness, end with happy endings and most of the time it’s not sugar-coated like that.

In my opinion, truthful endings to truthful stories are what make great literature.

I think all the best stories have some grain of truth to them.

Growing up I had limited experience with mental illness. I did not have the understanding of how mental illness works or what is happening in the person’s mind. It wasn’t until I read Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story, “The Yellow Wallpaper,” that I finally started to understand. While I haven’t personally had much experience with YA novels dealing with mental illness, I do understand how literature can affect how someone views mental illness. In my case, “The Yellow Wallpaper” helped me to understand that those who do suffer from an illness may not be able to deal with it by themselves but may need more professional help. It gave me a greater understanding of how complicated the mind is.

chikkabooo,

I’ve never thought about “The Yellow Wallpaper” that way before! I’ve taught that particular story to grade 12 students before, but never considered how it might make them think about mental illness in particular. (It was always structured as a study of mood or tension etc.) Did you find that it left you with a more negative impression of mental illness?

I don’t know if I would say that “The Yellow Wallpaper” left me with a negative impression of mental illness. Rather, it showed me that mental illness is more complicated than I originally thought. And I guess the fact that it is so complicated could be positive or negative depending on who you are. For me, “The Yellow Wallpaper” showed how sane the thought process of the women was and how her mind slowly declined into a state of mental insanity. The women herself was not crazy, but the mental illness made her seem as though she was.

This article resonated with me as I grew up observing mental illness at a distance, never being exposed to its true nature or how it plays into the individual’s life. I had seen it perceived as malicious with the mindset that one should fear the unknown. Over the years, I began to understand it in a great new light. I believe that because those with mental illness have both the opportunity and hardship of seeing things with a different perspective, they have something unique to contribute and develop in the world. They have an extremely relevant place in today’s society that I am glad we have begun to recognize.

Well said! I like the idea of seeing things from another perspective.

Romanticizing mental illness is dangerous, especially if it’s essentially just a means for landing a person that will magically ‘fix’ the protagonist. That being said, I think that you’re right in that sick lit in YA novels has moved away from that mindset. Now the story is about self reflection and overcoming a huge hurdle within oneself. Not necessarily fixing a mental illness because more often than not, it’s never going away. Sick lit has now allowed adolescents to relate to others that are going through the same thing as them, and learn how to deal with it in a potentially healthy way.

I really liked this article! Mental illness played a huge role to controversial works by some of my favorite authors like Plath and Sexton. It made me think about the original sick-lit novel, “The Bell Jar”.

I hadn’t thought about “The Bell Jar” as sick – lit, but that makes sense!

YES! Loved this article. It is really great to show the depth and span of YA lit because I think it goes underappreciated so often. Great piece.

Thank you!

“Sick lit” is a new term for me, but it’s apt. I would argue that “sick lit” has become one of the most popular genres out there, especially for teens. It doesn’t even have to be about mental illness. As a teen in the early 2000s, for example, I encountered a lot of romance books about girls with cancer. (I never read them; I’m medical-phobic due to traumatic childhood experiences). Books like The Fault in Our Stars have only added to sick lit.

I wonder what makes sick lit so compelling? Certainly, I think the article makes a great point about it giving voice to characters with mental and other illnesses. Unfortunately though, I think society at large still reads sick lit out of morbid curiosity or an attitude that says, “Thank God that’s not me/my kid/my loved one.” The good news is, the more quality sick lit is available, the more morbid curiosity should give way to real understanding.

Mental illness is something that hits close to home for me. I am so happy that literature is finally shedding light on the truths of mental illness and beginning to work to get rid of the stigmas.

“Finally”? What do you mean “finally”? This has been a topic in literature for ages. Disability Studies, on the other hand, is a relatively new approach to the issue.

This piece immediately brought to mind Hyperbole and a Half: Unfortunate Situations, Flawed Coping Mechanisms, Mayhem, and Other Things That Happened by Allie Brosh, which takes form in a hilarious series of anecdotes. As you say in your article, “the best narratives are relatable” and I think Brosh does just that. The entire book deals with her depression and one sort of arc that’s it’s taken in her life. At the moment where the readers would suppose–because we’re conditioned by other narratives–that Brosh will have a grand epiphany to share about how to get better, Brosh instead opts for a story about a pea that ends with “Maybe everything isn’t hopeless bullshit.”

These alternative sick-lits or new-age sick-lits are so important because prescriptive narratives can be so isolating to those who have the same condition but can’t “fix” it the way that the narrators do.

Also, thanks for including a list for further reading. I’m definitely going to check some of them out!

Smart address to how normalizing helps remove stigmas associated with ignorance and generalization. While children’s lit and YAL will continue to be subjected to protracted but idiosyncratic arguments about what’s “appropriate,” including the conversation about “sick lit,” Mead points to ways that normalizing will likely have a positive effect on critical categories and Gen Z dispositions to issues of race, class, sexual orientation, and more, including psychology.