Monster Party: Modern Games, Take Notes

Some history

Games on the Nintendo Entertainment System (Famicom in Japan), NES for short, were not always considered “retro games,” with the system’s final licensed title released in December of 1994 (Wario’s Woods, a mediocre Nintendo puzzler). In less than two years, the Nintendo 64 would be released, popularizing the next-next generation of games (don’t forget the Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis, the big consoles after the NES), and Sony’s 32-bit PlayStation would actually come out the same week as Wario’s Woods in Japan.

The Famicom first launched in Japan in 1983, with its North American counterpart brought to stores in late 1985, where it would continue to be sold for ten years, making it one of the best-selling game consoles of all time.

As early as 1996 and 1997, NES games grew in popularity as retro game forums began popping up over the infant modern internet, allowing fans of older games to meet and talk about their favorite games and collections. Thus, the system never really went out of fashion. Over the years since the late 1990s, retro gaming has grown in popularity, and many video game fans not even born during the NES’s lifetime are familiar with several of the system’s most popular titles.

Some of the most well-known titles include Super Mario Bros. 3 (1990), Metroid (1987), The Legend of Zelda (1987), and Mega Man 2 (1989), games that launched series’ that are still wildly popular today, among some lesser known but still very popular titles like DuckTales (1989) and Contra (1988).

Monster Party

Monster Party (1989) is an average action-platformer, a relatively obscure Bandai game that has earned a cult following over the past ten years via its internet fanbase. It is very rarely remembered as an NES or retro “classic,” but those who played it will never forget the experience.

While boasting very ordinary platforming gameplay (players run, jump, blast enemies with projectiles, collect power-up, etcetera), Monster Party‘s popularity stems from its bizarre tone and graphics, turning an average gameplay experience into an unforgettable romp through a campy, 8-bit hell. The game focuses on parodying horror pop culture and iconic cinema, but does so with such non sequitur strangeness that the game almost becomes unearthly, mystical, and certainly like nothing else players have experienced.

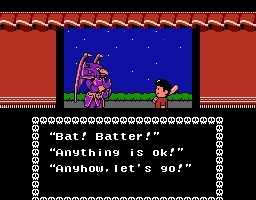

The game begins with a series of short dialogues between Mark, the young baseball bat wielding protagonist, and Bert, an inter-dimensional traveling warrior gargoyle. Mark is approached by Bert on his way home from baseball at dusk. Bert asks Mark to come with him to another world to fight evil with him, but Mark replies that he has no weapons. Bert points to Mark’s bat and tells him that that’s good enough and then whisks Mark off into the night sky.

The opening is weird, sort of charming in its naivety and quirkiness, and seems to suffer from a strange Japanese to English translation. The sentences ram into each other with little regard to verisimilitude, character building, or even logic, and before players know it, the game has started.

I’m going to forgo simply describing every strange detail in the world of Monster Party, as I’d be here indefinitely describing every single sprite and tile in the game. Rather, I’m going to focus on one particular aspect of the game and why it’s important, and how other games (and their developers) could learn something from it.

The flow of Monster Party‘s gameplay differs from most traditional platforming games in that each stage has a number of doors in it, some of which lead to boss fights. Players must explore the doors, find and defeat all the bosses, then receive a key that opens the next stage. The game controls well, somewhat surprisingly, but the game’s pacing and entertainment level (only in terms of the gameplay at its most bare) are much lower than that of Super Mario Bros. 3, for instance, which features very fluid gameplay and innovative level designs.

The boss dialogue

The meat of the Monster Party experience lies in the boss battles, or not even the battles themselves but the boss dialogue before the fight begins. Before each boss fight, the boss will proclaim or exclaim via comic book word bubble something absolutely insane, whether it’s a vague reference to a film, an awful, awful pun, a very rare hint, or just something completely random and arbitrary.

As the game progresses, players increasingly play the game just to hear what the next boss has to say, long forgetting the “plot” involving Bert’s world that had little ground in the game’s reality anyway. Rather than the plot pushing the game’s narrative forward, it is this series of strange, tiny bits of dialogue that make up the narrative, a maximalist collection of absurdities in the guise of a minimalist fiction. Compared to most NES platformers, Monster Party features a lot of text, but for an NES game with text, it is quite scant.

There are no character arcs, sub-plots, or even really thematic devices, let alone a three-act structure. Monster Party is an exercise in “style as substance” rather than “style over substance,” as, again, the meat of the experience are these quick bits of dialogue. They are not even truly dialogue, more akin to monologue, and even then that is not quite right.

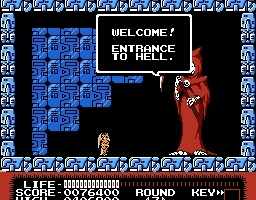

The first boss, a giant man-eating plant that is a reference to The Little Shop of Horrors (1960), utters only two words, “Hello! Baby!” with the two exclamation points only serving to diminish the text editor’s credibility. One of the most notorious bosses in the game, a trio of hopping, giant, possessed fried food murmurs “Look out baby. Here I come,” before bouncing toward Mark. Toward the end of the game, an oversized Grim Reaper tells Mark “Welcome! Entrance to Hell,” which is both shocking due to its fragmented nature and the fact that Nintendo did not censor it (Nintendo of America was known for its strict censorship of language, violence, religious imagery, and suggestive themes in the NES era).

Many of the bosses feature the use of puns: the Giant Bull Man of stage three, a disgruntled minotaur, says “Mooove it!” an obvious pun relating to cows, while a jack-o-lantern boss whines “Please don’t pick on me,” emphasis on the pick. Get it? Some of them follow even less logic, like the giant caterpillar in stage seven, that says “I’m Royce,” before proceeding to roll around the boss arena. Players get that the pun refers to the Rolls-Royce cars, but that still doesn’t explain what the pun has to do with horror, parody, or the history of cinema. It just doesn’t make sense.

Still further down the road of non-logic are the mummy boss (“My legs are asleep!”) and the samurai boss (“I…am a slowpoke.”), whose text seems to not be referring to anything, giving the bosses these vague but unique personalities.

This personality is the key to understanding Monster Party‘s charm. The game is vague, and very special, an almost scatological garbled mess of 8-bit one-liners, filtered through an awkward English translation. It sometimes parodies movies and horror icons, but more often than not, this concept is simply not there, or at least not transparent. At times, Monster Party almost feels as if it weren’t made by people, instead put together by alien software with random algorithms.

The game becomes astonishing when players remember that humans made every decision when putting the game together. There is a common trope belief that weird media must be the product of an artist on drugs, and on occasion that is the case (one need look no further than Alejandro Jodorowsky or William S. Burroughs), but Monster Party cannot be explained away with rumors of LSD in the office. The game follows its own set of rules and logic, but they are a set of rules and logic that cannot be pinned down or fully understood.

While Monster Party is certainly a unique gem, an obscure cult game for the NES, and that alone gives it its notability and notoriety, Monster Party serves as an interesting and useful example of how to use minimal text efficiently in a video game.

Text in contemporary video games

Most contemporary games, The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword (2011) always being my victim on the subject, feature a lot of text, usually too much text. A game like Skyward Sword has a lot to explain – it features a new system of combat utilizing the Wii MotionPlus, its quests are often convoluted and require extensive preparation, and the game’s plot is vast, with long scenes and many characters. Players are often forced to sit through slow explanations and averagely-written exposition when all they really want to go do is explore dungeons and find treasures.

It wouldn’t be fair to hold Monster Party and Skyward Sword to the same standard and claim that Monster Party is just right and that Skyward Sword is too wordy. Skyward Sword has an exponentially greater amount of information to relay to its players that simply does not exist in Monster Party.

So what can Skyward Sword learn from this creepy old game? Monster Party does not have a lot of text, but the text it does have will stick with players for the rest of their lives. The crummy jokes, the nonsense, against the absurdist horror background of the game’s world, will live on in players’ heads for years to come. The text in Monster Party has impact, even if the writing isn’t necessarily objectively “good.”

The writers for Monster Party pack in so much personality, charm, weirdness, and haunting mysticalness with each boss’s statement. In other words, players get the most “bang for their buck” per word here, probably more so than in any other game on the system and beyond.

Some games take dozens of minutes to expand on a carefully crafted but ultimately convoluted fantastic world and its characters. If the writing is interesting, refreshing, and feels genuinely special, then the game can take as much time as it wants (Grim Fandango is a great example everyone can agree with, Xenogears being a great example a few people will agree with), but this is rarely the case.

Monster Party then becomes something of a disgusting, schizophrenic haiku, a minimalist masterpiece, a humorous exercise in the simplicity of excess and kitsch. It never wastes the player’s time when conveying its mood, tone, and personality.

Dark Souls (2011), as well as its sequel Dark Souls II (2014) and the earlier Demon’s Souls (2009), greatly aims to never waste the player’s time with text, and for the amount of lore and characters present, there is very little text in the game. When the characters do speak, it is often a very short conversation with much impact. The non-playable characters (NPCs) are a weird bunch, mystics, warriors lost in time, philosophers, thieves, rogues, and displaced royals, all with their own secrets and personalities. Yet, Dark Souls never holds the player from the action and exploration, and the game feels fresh and deep.

Dark Souls is a larger and much more complex game than Monster Party, but the minimalist approach to narrative in Dark Souls is evident, and while Monster Party barely even has a “narrative,” the games are closely related in this way: a minimal level of text, and the text that is present packs a real wallop.

Modern games, take notes

Many players could easily pass Monster Party by, writing it off as a weird-looking, old, mediocre platformer, and that is essentially what it is. But Monster Party revels in its weirdness, more so than any other game in such a genuine way. The game certainly holds a cult status among retro gamers and collectors, and it pops up in retro gaming news every once in a while (recently, a new Japanese prototype cartridge was sold on an auction site for a large sum of money).

What Monster Party lacks in fluid and “fun” gameplay, an oozing fantasy plot, and iconic heroes, it more than makes up for it with its wild, no-rules tone and mood. It is a testament to text in games, and how a minimal amount of text can be used to produce an extraordinary atmosphere.

Monster Party is a “retro” game that is worth a look for contemporary game players, and in some ways, the game doesn’t even feel particularly retro. The game’s humor is universally awkward, and will never go out of style because it was never in style. Its references are so sporadic and vague that someone playing the game when it was released versus someone playing it now will have essentially the same experience. No one ever will be able to “relate” to this game. The game could’ve been made yesterday, ten years in the future, or one hundred years ago by extraterrestrials.

The game is a morally ambiguous text, a mystical text, packaged in otherworldly kitsch and NES graphics. It has no apparent meaning or agenda, and no ground in reality, but is nonetheless incredibly large and special. And it achieves this status through only a couple weird sentences.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

There are good games, there is Monster Party and there are bad games!

It’s so ambiguous. Is it good, bad, just, or evil?

I never really made it past round one when I was a kid. Yes, I am completely serious. I never passed the FIRST FLIPPING ROUND.

This game can either bad hard as f*ck or easy as cake, you need to know how to kill the enemies, they have flaws and yourself can initiate proper evasive tactics against them. Sometimes doing the worm can save your rear against some enemies. Try counter attacking some of the bosses with their own medicine, what ever they throw at you. The Shrimp, Onion Ring and the Stacked fried donuts or whatever it is, lay low until they pass you, then slightly get up and jump behind them and batter up. Theres more to each enemy and boss but I can go on forever.

You can farm health from respawning enemies, and yeah, getting on the ground sometimes makes you invincible. For bosses, just get on them and keep attacking, don’t worry about timing your hits or anything. Just go nuts…

/ArtFAQs

You know the game will leave you very disturbed and confused and i regret looking it up. alot of child hood trauma here i don’t want to talk about it.

I kind of wish game’s these days were like this one but more polished.

Hell YES I’ve beaten this game. the last level is out of control but well worth the suffering. fun game!

There’s so much anti-spirituality/parody religious imagery in the final level – that could easily be a whole other article! I’m glad you know what I’m talking about hahaha…

This is wonderful. I would have loved this game had I known about it when it was originally released. I’m surprised it was never on my radar. I’m really looking forward to giving it a try.

; )

Wow, that was really great, being able to pull a profound game design lesson out of a pretty freaky, mediocre NES game. It’s good to be reminded of the importance of simplicity in games, and the attention and respect necessary for what the medium is—and isn’t. A game is by definition a challenge. If you’re not being challenged and you’re not interacting at the expected frequency, then it’s not a game. This really makes me wanna check out Dark Souls now too, especially after the disappointing rhythm of Skyrim.

Demon’s Souls and Dark Souls are really super and special.

I first heard of this game from the video review by JonTron. After reading this I have to assume this game is interesting, but I’d rather look from a far than actually experience it. Though games nowadays could use a bit more personality…other than grimdark and broody.

I think it’s worth a few moments of your time to actually try and play it. It’s almost a shame that people could read this article (or any other article) before finding the game, not knowing what it is, and playing it for themselves. I’m probably doing a disservice to it ;^|

Definitely a big difference from Super Mario World.