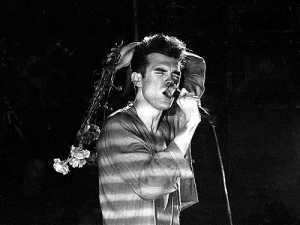

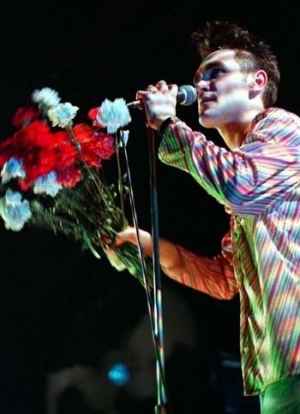

Morrissey the Ecologist

Pop singer/lyricist Morrissey, famous both as a member of the 80’s band The Smiths and as a solo artist, deals with many of the themes that crop up throughout his lyrical output in his recently published Autobiography. One issue that is interesting to look at in this work is in his meditations on the dialectic of nature versus industry. While most people either love or hate Morrissey, what he does offer in this section of the text is worthy of closer examination for it can help us to think through the dilemmas, both psychological and ecological, of industrialism. As we shall see, this small section of his work reads as a powerful and prescient analysis of the human dilemma amidst the ecological crises that befall us due to our industry.

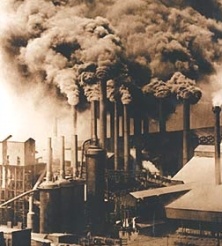

The section of Morrissey’s Autobiography in question occurs as Morrissey records a memory of 1989 when he and three friends visited Saddleworth Moor in England. From the start of Morrissey’s voyage to the moor a palpable sense of trepidation is recorded. Morrissey begins this section recounting the specifics of the journey, moving from the “traffic-fume toxic” of the city to the “wild spirit” of the Saddleworth Moor (Morrissey 229). Notice an interesting paradox Morrissey introduces in these images: the “toxic-fumes” of civilized society shall be developed as deeply ironic, for that civilization which supposedly protects us from the “wild spirit” of nature is lethal to our lungs. The literal journey Morrissey records makes clear the central philosophical tension of this story, which is that between industrial/natural. Morrissey writes at the start of this section that “[t]hese moors have another life, and that life is very much apart from the one you may have just left in Manchester, Bradford or Huddersfield” (Morrissey 229). Already there is a split made between the “civilization” of the city and the primal power of nature. Put in another sense, Morrissey is punctuating the difference between the industrial mode of survival, which pervades the early sections of the Autobiography‘s ruminations on the harsh life in Manchester’s industrial environment, against the mode of survival necessary in the natural world untouched by human industry in the moors.

After this introduction, a fog descends, figuratively representing confusion and alienation that this group of four feels as they enter the older mode of human existence. The natural harsh world which technology has made obsolete, a memory of the Paleolithic only to be grasped in the comfortable temporal distance of museum walls, is now to be faced head on by these travelers. Just as Morrissey’s journey is from industry to nature, it is also a journey back into the memory of humanity’s evolutionary struggle for existence against the force of the moor.

Curiously Morrissey notes that as they approach closer to the moor, there is as sense of “shame” because “some would have preferred to have left but could not” (Morrissey 230). The pull of the comfort of the industrial world in which these travelers were born, and to which they desire to return, brings up shame precisely because the moor proves how weak industrialism has made them, and, by extension, how weak industrialism really is against the ever-present force of the natural world it attempts to subdue. Man has simply become the custodian to his machine-made comfort now which, while it loosens him from the struggle to survive in the moor, also deadens him to that which is natural in the intoxicating false fumes of a constructed safety he has built for himself in the toxic fumes of civilization.

Morrissey proceeds to expand on this point as he writes of the sheep he sees in the moor, pondering “[a]re there such things as ‘wild’ (as in ‘free’) sheep? Impossible to believe that no greedy landowners would see this sturdy family of sheep and not want to butcher them, as it is impossible to believe that any moor animal would be left alone to live as it must” (Morrissey 230). The idea of freedom and wildness come into play in this quote, and could be added to complicate the central tension of industrial/natural. Who, in this situation, is free? Is naturalness necessarily connected with freedom, and does industrialism, therefore, necessarily constrain the “natural” notion of freedom in favor of the comfort and power over the natural landscape it affords man (a kind of power that could take these sheep and butcher them)?

Morrissey broadens out this vision of the sheep and further complicates these notions in the next section, as he proclaims that the “sheep know more than we do about this barren moor” (Morrissey 231). The tensions only peripherally glanced at until this point become very clear as Morrissey notes that while the sheep survive in the moors man is “trapped by it” because “metal and stones and slabs are all that we know. Nature would kill us—as we are killing it” (Morrissey 231). Man has made nature the greatest threat to his/her technological safety cushion, to which he/she cannot return without trepidation, as these four have experienced in their drive to Saddleworth Moor. The sheep represent a grave threat to industrial humanity in their strength against this natural threat. The sheep, at least, still have the ability to survive in the natural world which man believes he has made obsolete with his technology and industry. Morrissey uses this vision of the sheep to critique industrialism, turning the tables on man’s supposed superiority over the natural world, by stating that once man enters the moors he knows “how animals feel when they are trapped in a city” (Morrissey 231). Man is now the one boxed in by nature, it is only within his own idea of civilization that he escapes reality of the natural world that still lingers in these desolate moors where man’s grasp is shown to be weaker than is assumed within the safe intoxication of the smoggy metropolis. “These moors you will not control” Morrissey proclaims to humanity, “and something about the chilling darkness makes the motorist lean inwards—away from the window, where you thoughtfully check your own reflection to make sure that it is indeed yours” (Morrissey 231).

This quote makes clear that this tale could be easily read both as an ecological manifesto and as a statement on the ontological anxieties industrial man faces. In forfeiting the natural world, man has constructed his/her own sense of identity in opposition to the forces of nature. When the grip of civilization falls to the overwhelming power of the moors, then, what will become of man? This is a great question to consider as we are steadily advancing in propping up civilization throughout the world against the natural rhythms of nature’s cyclical self-regulation. As the world of man becomes increasingly mechanized and dependent on more complex modes of technology, we must wonder at what we are losing, or perhaps what we are fearing, in our endeavors. We must also consider what we stand to lose when nature rears its head again, disrupting our technological bubble with its thunderclaps, earthquakes, and tsunamis. In constraining the natural world by technology to such an extent, literally enclosing the world itself within a womb of satellite security against the universe at large, we stand to lose all if nature overpowers our systems. In propping up human identity via his technological advances against the vast infinitude of the natural cosmos, the nature that still “is” becomes an even greater threat not merely to human identity, but also to human survival.

This may be why at the end of Morrissey’s tale he recounts the vision of a ghost boy. As these voyagers into the moor are all driving away they are haunted by a “wretched vision of sallow cheeks and matted shoulder-length hair, a boy of roughly 18 years wearing only a humiliatingly short anorak coat that was open to expose the white of his chest and the nakedness of the rest of his body” (Morrissey 235). What is important in this tale is not so much what or who this boy is, but what he represents in considering the themes of nature and industry we have been exploring thus far.

The first reaction of these four friends to this vision is to question how could anybody live in the moors (Morrissey 235). The boy’s paleness and nakedness stand in stark contrast to the vigor exhibited in the sheep earlier. The boy, a young man, and thus an archetype of vigor and life in so many human cultures from the Greeks onward, is severely de-lauded within the moors. The boy cannot survive, for even as these four noted in leaving the moors, humans has become “soft creatures of habit, and we must return to enclosed surrounds of locks and bolts and alarms” (Morrissey 234). When the thought that this vision of a boy was not real, but was indeed a vision of a ghost, Morrissey writes “[w]e know this to be true, and our hearts sink” (Morrissey 237). In the metaphorical sense, the boy is a ghostly vision of man in his primal state, struggling against the force of nature to survive, despite his frailty before the immense grandeur of the natural universe. The boy, then, also doubly represents the degree of separation modern “civilized” man has made for himself to nature in building a society that purges such evolutionary traumas from the human psyche in its smog and cement of industrial labor. In the boys frailty we see clearly that blackness the motorist sees in regarding, with the aid of the vision of the moors, himself. The horror of the ghost is in its very literalness, the very literal threat nature poses to civilized man’s precariously built industrial womb, and the psychic reality of humanity’s fear over the existential morass that the primal power of nature forces upon our frail mortal identity. As Morrissey said himself in this tale, in the moors “nothing is metaphorical here–the threats are literal” (Morrissey 234).

In analyzing this short episode in Morrissey’s Autobiography, we can see that this text contains great moments of insight into the human condition. Especially, if nothing else, we should learn from this tale to take the ecological systems seriously as we are increasingly becoming more conscious of the threats our industrialism poses to the natural environment. We must learn to live with, and not against, the natural world. This short tale reminds us of the force of nature we can often forget within the habit of industrialized mode of existence, and forces us, just as the visit to Saddleworth Moor forced Morrissey and his friends, to question what our goals are in building up our industrialized society. As Morrissey put in an early lyric: “Amid concrete and clay and general decay. Nature must still find a way.” And, indeed, nature, as it always has, will probably triumph in the end. Then how are we to prepare or transition out of our hyped up technological dependence? Man’s tenuous grasp of security with his paradoxical safety in the toxic fumes of the industrial womb is always in danger of being punctured by the ever-present existence of the natural world. Morrissey’s text here does not propose as solid solution, rather it offers a very timely critique of human industry as we continue to debate the issues of global warming, pollution, and other ecological crises, as well as the ontological, evolutionary, and psychological effects on man in the industrialized world. Such issues will only grow more important to answer in substantive ways as we swim along within this machine of our making against the currents of the natural world.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Morrissey is a very gifted writer (as well as a gifted singer songwriter).

Morrissey’s writing is lyrical and figurative and expected, and his choice of words are very nice and pleasant to read. But, it was soooo hard to read the book because he’s so full of it.. He comes across as arrogant a lot of the time, but that I can not let that discredit his clear talent of being able to put together words and have the come out in utter beauty.

As much as he hated his Catholic school, they sure taught him how to write well!

As someone who was a fan of the Smiths and was brought up in Manchester about 10 years after Morrissey went to school there (not in Stretford but the other side of the city) I always thought his view of it was more akin to Manchester in the 1950s or before. He certainly does wax lyrical and exaggerate about the place, it’s a caricature, like an episode of Coronation Street (always 30 years behind) ‘Kes’ or ‘A Taste of Honey’. But attending school and sixth form there was a million miles from Morrissey’s experiences of it. He was most likely victimized and picked on, like in every school, kids can be cruel. So what? Happened everywhere, happens even now. And what’s even more ironic is his hatred of Thatcher (like other famous Manc pop stars like Mr Hucknall and those 80s ‘socialists’ like Billy Bragg and Paul Weller.) but he is happy to collect his money, hard-earned and deserved yes, but still a little hypocritical since he made it singing about his left-wing politics.

“he is happy to collect his money, hard-earned and deserved yes, but

still a little hypocritical since he made it singing about his left-wing

politics.”

Eh? I think you’re confusing having some left-wing sentiments, with some branch of devout Catholicism, practised in Assisi, or a full-on revolutionary Marxism. Left wingers don’t believe earning money is bad, they just think they and/or (other) poor people deserve more than they’ve got. Marx simply got bonkers, took the valid analysis of inequality too far, and claimed all property would and should be abolished.

Making a good living was hardly invented under Thatcher. There were rock and pop stars in the 50s, 60s and 70s you know.

Great analysis and great site that lays somewhere between entertainment coverage and academia.

I love Morrissey even more deeply than I did before. He has been part of my life since I was a wee preteen, and like most of those who love him, I feel quite close to him through his music. Now I feel like he is a close friend that, alas, I will probably never meet.

This is an outstanding article and I hope everyone reads it.

I love Morrissey, but it takes balls to be vulnerable and self deprecating, in terms of either he did not deliver and I am disappointed. His victim complex and inability to see his flaws really ruined the autobiography for me.

But no surprise, that being his lifelong m.o. But I do like his music, if not his prose.

Nice work.

Morrissey could paint pictures of the North I found utterly truthful. And he made me laugh with it. He was never miserable.

He should probably move to Goole or somewhere to rediscover his subject matter.

I wonder what would have become of him if his parents didn’t have to Leave Dublin for Manchester to find work? Front man of a different type of U2 perhaps

I haven’t read the book and I don’t know much of Morrisey’s writings, but fascinating article nonetheless.

Very good article. Moderation in all things: without technology, we’re all dead of disease at 30; with no laws protection ng us from unrestrained technology, we’re all dead at 30.

The general spirit of the 1960s (even though this wasn’t his era) very much looms large over him.