Rowling, Tolkien, and Foucault: What is it to Hear the Author Speak?

Though it may seem hard to believe, the idea that a story’s artistic responsibility — as well as credit for its creation — rests on an individual author is relatively young.

For millennia worldwide, information has been passed along from storyteller to storyteller, bard to bard, and teacher to learner, by way only of listening and remembering. Before stories were written to be read, any existence of an author as “original creator” (with important exceptions) ordinarily either wasn’t known or wasn’t important to the ones listening; the oral-aural practice of storytelling was the prevailing feature, and the question of origin was left to tradition.

History, folktale, philosophy, and anecdote were heard and repeated, passing through social groups and families for entertainment and education. With the cultural shift toward the more capacious and seemingly permanent written word as the dominant medium, the concept of Literature emerged, and with it, the role of Authorship. Pictography, then scribes and recorded language have of course existed for as long as there have been people telling stories, but the uniquely double-edged sword of authorial identity was only constructed in the past few hundred years.

Harry Heresy

One of the most fascinating artistic relationships is that of fan interaction with a living author. Authorship by itself is already complicated, and the problem of intellectual property only grows ever more complex with the expansion of all forms of media. In light of the entanglement, how do we reconcile fan-made contributions to literary canons? What if the “author-and-creator” is in touch with these fans, and can speak about the creative process? Arguably the most widespread fan-author interaction of this generation occurs surrounding J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series.

Within the past few weeks, Rowling herself said in an interview that her character Hermione Granger may have been better-off in a relationship with Harry than with her eventual canonical spouse, Ron Weasley. Rowling herself, and the headline for The Guardian’s article, calls the comment “heresy,” almost implying that there exists a romantic, artistic, and literary “doctrine” of Potter appreciation as something apart from Rowling and her books — something that the original author herself can violate! To turn an overused phrase, the fictional Potter world has evidently come into a life of its own.

Granted, readers’ speculation and controversy over the lives of characters is nothing new. Anecdotally, Charles Dickens was often approached by avid readers of his serials who begged him to spare the lives of their favorite characters, or at least to reveal what his authorial fate had in store for them. Knowing Dickens, though, few of his characters ever led charmed lives, so it’s hard to know why anyone bothered. Readers’ deep investment in fictional worlds is a major enigma driving the creation and study of literature, and the existence of a speaking author makes the problem even more puzzling.

Rowling caused some earlier controversy when a law firm accidentally leaked her name as the writer behind the pen-name Robert Galbraith, “author” of The Cuckoo’s Calling. The novel itself, a crime-fiction, flew under the radar for three months in the Summer of 2013 before Galbraith’s identity was leaked. Rowling called the experience of writing under a pen-name “liberating,” and expressed her disappointment that she could not have remained incognito as Galbraith for longer. Sales of The Cuckoo’s Calling spiked after the revelation, naturally, which evoked frustration in struggling independent authors. Many felt that Rowling had used her security with publishers to unfairly stake out a niche apart from Harry Potter, citing the unremarkable pre-revelation sales as evidence that the book owed its success to Rowling’s name rather than to the quality of her writing.

Rowling desired the “liberating” feeling of pseudonymity (not quite anonymity), but what exactly did she want liberation from? Differing from the famous examples of the Brontë sisters, Mary Anne Evans (George Eliot), and Louisa May Alcott, who published under male pseudonyms in order to have their work taken seriously, Rowling assumed a man’s name for the opposite reason: Rowling wanted new scrutiny, independent of her past success. It seems as though Harry Potter‘s world got away from her, in a sense, while still being too closely tied to her name to allow for independent criticism of her new work.

After a monumental project like Harry Potter, any creative expansion outside its world would be difficult to view without the Potter lens. Here, again, we run up against the problem of authorship; the entire issue of Rowling’s controversy hinges on her identity as sole author, and in readers’ desire for consistency in the work of a productive creator.

“A Nonsensical Tower”

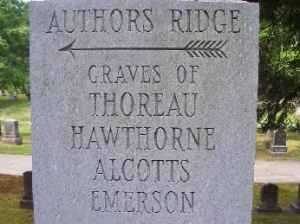

The implication of consistency makes an author’s name powerful. Being able to name a well-known author in conversation activates that author’s whole body of work for discussion: you say, excitedly, “I just bought some Dr. Seuss,” and it means something quite different from, “I just bought some Shakespeare.” Referring to bodies of writing by authors’ names treated like mass-nouns is odd — that’s a device called metonymy, where an associated figure stands for something greater. Not that a person can’t enjoy both Hop On Pop and Julius Caesar (I know I do), but authorial names stand for much more than the combined content of individual texts.

To say you are reading Shakespeare is to invoke sociocultural associations with the incidental things related to Shakespeare: intellectualism, Romance, and the Renaissance, to name the bare minimum. Dr. Seuss is at once associated with whimsicality, children, and social commentary. The practice of metonymy with authorial names and their work nearly argues that there should be some sort of consistency in ideology, content, or style within the literature produced by one person. Rowling’s case seems to indicate that the expectation of consistency is very real, even that it drives multi-genre authors to need more than one name. A genre is, after all, an agreement that artists will fulfill expectations.

Did you know that the existence of the Lord of the Rings trilogy depended upon demand from a fan-base? Allen & Unwin’s publication of The Hobbit in 1937 was met with such enthusiasm from readers that the publishers pressed Tolkien to write a sequel. Tolkien at first was reluctant, but eventually revisited the Baggins family’s storyline in light of larger-scale themes he’d been developing since before The Hobbit in his then-unpublished Silmarillion.

The “sequel” grew, then became a vastly different kind of story than The Hobbit ever was: darker, with higher stakes, and in a more mythological vein than its children’s-story-style predecessor. Against Tolkien’s initial inclination, The Lord of the Rings was too long to be published in one book, and had to be split into three volumes (ironic considering the reversal of circumstances in Peter Jackson’s film trilogy of The Hobbit). Though The Silmarillion, finished by his son, Christopher Tolkien, was published only posthumously, it stood as the foundation for all of J.R.R.’s writing on Middle Earth.

Along with a robust biography that is both humbling and inspiring, Humphrey Carpenter edited a published collection of Tolkien’s letters. These include correspondence with his family and University colleagues, with his publishers, and (arguably the most interesting entries) with fans asking questions. Tolkien went to extreme lengths to explain every last detail of his universe to loyal readers, fleshing out vivid mythical and historical minutiae without hesitation. Fans and friends would write to him in Tengwar (Elvish script), and he would write back. If any author in the history of literature strove for consistency across a body of fiction, it was J.R.R. Tolkien. Tolkien, though, was motivated by an uncommon creative impulse.

In Beowulf and the Critics, Tolkien wrote:

A man inherited a field in which was an accumulation of old stone, part of an older hall. Of the old stone some had already been used in building the house in which he actually lived, not far from the old house of his fathers. Of the rest he took some and built a tower. But his friends coming perceived at once (without troubling to climb the steps) that these stones had formerly belonged to a more ancient building. So they pushed the tower over, with no little labour, and in order to look for hidden carvings and inscriptions, or to discover whence the man’s distant forefathers had obtained their building material. Some suspecting a deposit of coal under the soil began to dig for it, and forgot even the stones. They all said: ‘This tower is most interesting.’ But they also said (after pushing it over): ‘What a muddle it is in!’ And even the man’s own descendants, who might have been expected to consider what he had been about, were heard to murmur: ‘He is such an odd fellow! Imagine using these old stones just to build a nonsensical tower! Why did not he restore the old house? he had no sense of proportion.’ But from the top of that tower the man had been able to look out upon the sea.

According to Tolkien Scholar Michael Drout, Tolkien’s view of Beowulf as a historically complex and deeply cultural text packed with ancient and often “broken” references was a major influence on his creation of Middle Earth. The Lord of the Rings is packed with references to myths, cultural tropes, and stories that characters in Middle Earth would have taken for granted, the way the Beowulf poet and his contemporaries would have had immediate associations with all its allusions.

According to Carpenter’s biography, Tolkien went so far in internal consistency as to chart phases of Middle Earth’s moon and its weather patterns to better know what characters all over the land would be able to see at any given time. Not only was Tolkien driven by reverence for his most beloved Anglo-Saxon poem, but as a devout Catholic he also saw the act of creativity as a spiritual obligation, as an act of honor and gratitude humanity could perform in acknowledgment of its own creation. Little did you know, Tolkien had a strong hand in C. S. Lewis’ conversion to Christianity, and thus the creation of The Chronicles of Narnia.

Who is Speaking?

Some food for thought: What is it to quote an adage or saying, and what weight does it carry in contrast to quoting a nameable author? What if you hear the author speak?

Michel Foucault explored the implications of the question, “What Is an Author?” in his 1969 essay by the same name. Among many “author-function” properties, he ascribes creditable identity as non-essential:

Even within our civilization, the same types of texts have not always required authors; there was a time when those texts which we now call ‘literary’ (stories, folk tales, epics, and tragedies) were accepted, circulated, and valorized without any question about the identity of their author. Their anonymity was ignored because their real or supposed age was a sufficient guarantee of their authenticity. … In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a totally new conception was developed … ‘literary’ discourse was acceptable only if it carried an author’s name. (125-126)

Foucault goes on to call the attribution of “authorial” qualities to the creator of a text merely “projections.” Granted, Foucault’s focus never falls upon living authors, nor upon the idea of personal interaction with an author. Foucault outlines the “author-function” inherent in texts and their meta-texts, as post-structuralists are wont to do, rather than making allowances outside a work itself.

Instead Foucault proposes questions he would rather readers and critics ask instead of questions of authorship and authenticity: “What are the modes of existence of this discourse? Where does it come from; how is it circulated; who controls it? … Who can fulfill these diverse functions of the subject? Behind all these questions we would hear little more than the murmur of indifference.” (138). Are the deep creative impulses we attribute to creators of texts no more than superficial projections, or does a new age of digital media and authorial interaction merit a different view of authorship?

Roland Barthes, only a year prior, wrote “The Death of the Author.” Despite gross misconceptions about linguistic science (it was the 1960s, after all) Barthes, like Foucault, describes the “modern” trend of the author disappearing into the work. However, Barthes engages more with the impact of a living, breathing writer:

Once the Author is removed, the claim to decipher a text becomes quite futile. To give a text an Author is to impose a limit on that text, to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing. … The reader is the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any of them being lost; a text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination. … the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author. (147-148)

Barthes believed in the primacy of the assembling, discerning powers of the reader, arguing authorship to be a multiplicitous and fatally-destined discipline. Drastic, perhaps, but that’s postmodern language for you. What does it matter that Barthes said it, after all?

Records in the Dark

The practice of taking in literature on a spoken recording rather than reading right from the page has existed practically since the dawn of recorded audio. It wasn’t until the 1980s, though, in the heyday of cassette tapes, that the “Audiobook” became a unique phenomenon. Rarely, though, do we hear the author of a work reading aloud anymore.

The author credited with the inception of popular recorded literature is thought to be Dylan Thomas. Thomas was known by many personal traits, including alcoholism and reckless charm, but aside from his eminently complex poems, most fans adored his voice:

Thomas traveled all over the US and Europe to perform readings, also contributing radio broadcasts and records. Arguably few, if any, readers could have done Thomas’ poems justice besides Thomas himself. Not only does the richness and depth of the nostalgic existential melancholy in “Fern Hill” translate perfectly in the timbre of his voice and style of his reading, but to conceive that we are hearing the voice belonging to the mind that created those words and felt them originally makes the experience wholly different than a non-authorial reader.

Similarly, there is a recording of Tolkien reading “Riddles in the Dark” from The Hobbit:

Around 1:54 Tolkien voices Gollum, giving the strange character an equally strange presence in sound. The writing of The Hobbit certainly suggests an eerie voice for Gollum, with hissing, coughing, and bizarre diction, but the tone of the voice is left up to readers’ imaginations. Andy Serkis, the voice of Gollum for the films, surely listened to Tolkien’s interpretation of the character’s sound before creating his own. The Hobbit itself began as a story Tolkien would tell to his children, so the inclusion of entertaining voices makes the text come alive in an all-too-different way than the solitary experience of reading alone, or hearing another reader’s interpretation.

The web is packed with lesser-known recordings of famous authors reading their own work. Walt Whitman’s resonant, grandfatherly voice, for example, reading from “America”, fulfills the robust and transcendent ethic of his work. T.S. Eliot’s thin, eccentric, meandering tones can also be heard reading “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”, giving a fitting voice to his icon of hesitation.

To bring up a rather meta-apropos idea, here I will again quote from Foucault’s essay “What Is an Author?” in which Foucault quoted from Samuel Beckett’s Texts for Nothing, in which Beckett asked,

“What does it matter who’s speaking?”

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Great read! Tolkien had a very ordinary life yet produced extraordinary tales. His love of the languages and good education helped him mold his stories.

Tolkien’s life work have served as both refuge and inspiration to me for as long as I can remember.

They certainly did! Reading his biography was at once very humbling and very inspiring. Being a linguist myself, it’s quite pleasing to see such a robust fantasy world built around the love he poured into language creation.

What an engaging writeup. Thank you!

This is such a fabulous article! I really liked the points you made, specifically about Rowling and her “speaking” as an author. I, personally, haven’t really thought about the impact of what authors say in regards to their work, so you have definitely provided some food for though. Thanks!

I’m pleased to be stimulating thought with this, and it means a lot that you say so especially — I loved your article on Rowling!

Excellent read! I have learned so much from this article, and I like the fact that you add actual recordings of the books. Reading is an actual experience and it is so different when you read a work aloud, or someone else reads it to you. It is performative in a sense like theatre, but in a more intimate way.

I couldn’t agree more. Hearing authors read is pretty uniquely captivating, isn’t it? Robert Frost was also a huge proponent of reading aloud as the only way to experience poetry, I’ve heard, which makes sense considering his fine-tuned sound and rhythm.

Yes!

Have you heard the Beat poets read their poems for example? I know Allen Ginsberg or Everett Leroi Jones base the rhythm of their poems on blues music and jazz rhythms, I would recommend listening to these two

Great read! Considering authorial intent is a very interesting endeavor and can certainly lead you down paths that otherwise be difficult to imagine. While it is true that sometimes ideas jump out of a narrative without the author, so to speak, taking the author into consideration can go a long way in understanding the bones behind body. As far as listening to the author goes, I think it can be a magical experience. While the words do typically stand alone, and often times a professional “reader” could do a better job reading the words on a page, but there is something about listening to the author, like Tolkien as you referenced here. You can feel the toil in the work as they read, you know how much they have invested in the words. I have a collection of cds of Tolkien reading his works and it is just wonderful to listen to him because you know how much it means. Really cool. Great job!

I love how you brought J.K. Rowling and Tolkien together in such a non-obvious manner in this article. This was very well-written and an interesting read.

I love the recording of Tolkien. The Hobbit was the first book that got me excited about reading, and Tolkien’s books have always been an inspiration. I always find that hearing an author read their work is so much more engaging that when I am reading on my own and in silence. When an author reads their work, you hear as they intended you to. But when you read on your own you have only the words the guide you, and how they sound is often quite different.

I was thinking the other day, in light of the recent scandal involving comments made by Lynn Shepherd against J.K. Rowling, about the force of fandom. Which, most of the time, is an exercise in passion rather than a proper employment of reason. I even wrote a blog post at franciscnona1.blogspot.co.nz, in which I reflected obliquely, among other things, on the facts of authority. Who has the authority to ask for writing to cease? This comes very close to your argument about the point where a writer’s work stops being their own and becomes a sort of public good and the object of what I call readerly xenophobia. Fans tend to do this. But, to follow your points via Foucault and Barthes, this aspect of passionate reading that hails the author and kills his/her detractors is a result of the C18th turn towards author as individuality. It is employed not only by fans. Academics do it too. They do it more professionally, and arguably with more serious results.

Now, there’s a noticeable trend these days towards collaborative writing, the Wikipedia type, which is attempting a return to older forms of storytelling. What do you think of this? Is communal reading/writing staging a comeback? Or is it just a new form of channeling creative energies towards lucrative purposes (as in the case of the individualisation of the author figure in the C18th)?

“Readerly xenophobia” is apt, especially in light of Ivory Tower judgments, as you say.

Wikipedia is unique in this discussion because of its multiple valences — not only does it present a fluid, communally-told (and regulated, supposedly) set of narratives for history, society, and culture, but it has hypertextual capability. Beyond the allusive power of an in-text reference or quote, Wikipedia literally links entire narratives together into what I suppose you could call a “collaborative encyclopedic discourse.”

Each textual page may represent the work of one author or a thousand, but Wikipedia at large is a fluctuating macro-text that by definition strives for internal consistency. Name-dropping an authorial canon invokes an ostensibly consistent narrative centering on an individual; name-dropping a print encyclopedia invokes one institution’s temporarily consistent narrative with all its values and limitations; invoking Wikipedia is something in media we’ve not conceived of yet except perhaps in Foucault’s Heterotopia. Even then, because Wikipedia is a living document, Heterotopia may even be too static. As much as the writing is certainly communal again, the medium carries too much of an unexplored message for me to be comfortable calling it a comeback.

This is a great article with a really interesting angle and a huge range of references! Well done, you’ve created a very enjoyable read!

You brought up some really interesting points about the relationship between the author and the readers that got me thinking. Cassandra Clare, author of The Mortal Instruments series, has a very strong presence within her fanbase and communicates regularly with them (I’m thinking of Tumblr, because she has a blog and answers questions from her readers and gives them inside information and previews into her work). Sometimes I wonder how this affects the way she writes the continuation of the story and characters – do the ideas of her fans influence her creative process?

Your comment about Rowling’s name being connected too closely to the Harry Potter series made me think about the actors in the movies and how they face the same dilemma. When I see Emma Watson in other movies it’s hard to dissociate her from her role as Hermione. It seems that people who are so invested in a single body of work will end up struggling to separate themselves from it in the future.

Thanks for the great read!

Thank you for providing such a thoughtful reflection on this subject. Erica referred me to your article because I’m in the midst of several Tolkien biographies, and I really enjoyed hearing him read about Middle Earth and give voice to Gollum. I especially love knowing that JRR corresponded with fans in his own elvish script! He certainly had strong opinions about the significance of authorship and defended them vigorously. Your article brought to mind is something I read recently in a Joseph Pearce biography of Wm Shakespeare. Where ever you stand on the question of authorship, I think you’ll enjoy the language of this excerpt from “The Challenge of Shakespeare,” his first appendix to that bio: “At the heart of much modern criticism, as practiced by a plethora of postmodern parvenus, is an irritation with the power of the author. If one is constrained to listen to the author one cannot do one’s own thing with the text. One must bow before a higher authority, the authorial authority. …Even when postmoderns accept the existence of meaning, and many don’t, they believe that the reader has as much “right” to interpret the meaning of a work as does the author. This is tragic, not for the work of literature itself, which retains its value regardless of the ways in which it is abused, but for the reader who is depriving himself of the full depth and beauty of the work he is reading and studying. In this respect it might be said that there are two types of readers: those who do things to books and those who allow books to do things to them. One approach is rooted in pride, and its illegitimate offspring, superciliousness and arrogance; the other in humility, and its fruitful progeny, wisdom and discernment. The former is self-deceptive, the latter receptive. Most modern criticism falls into the former category. If one believes that one knows as much as the author or has as much “right” to interpret the meaning of the text, or if one dismisses the intention of the author as being irrelevant, one will be squeezing the work into the narrow confines of one’s own prejudiced presumptions, doing things with the work to make it fit into one’s own limited weltanschauung. If, on the other hand, one accepts that the author knows more than the reader about his own work, one will be able to grow and to stretch oneself in the beautiful space that the genius of the author creates. After reading a book in such a receptive way, allowing it to do things to us, we will find that we have grown into someone wiser than we had been before we read it. All of this presumes, of course, that the work in question has literary merit and is worth reading.”

I don’t quite have enough words for how much I love your piece. I find it fascinating – especially the ways in which you illustrate the idea of metonymy as it functions with authors. I wonder what Tolkien would have to say about Jackson’s franchise, especially the Hobbit trilogy haha. Thanks for your piece! I want to read it again – so thought-provoking.

Great article! I’m certainly intrigued by the relationship between living authors and their works as well. Going back to your discussion of J.K. Rowling and how the Potter series gained a “life of its own” – I couldn’t agree more! I don’t know if you’re familiar with how widespread and vast Harry Potter fanfiction was/is, but it is BIG. While the books were still being published and after, fans created their own endings, their own alternate universes, original characters, etc. HP fanfiction now will designate when it was written (such as post-Half Blood Prince, which implies it’s not compliant with the final book).

Rowling is aware of all the HP fanfiction, and flattered from what I understand. I would surely be. However, she made a comment once to fans about being “concerned” for how certain characters were being popularly portrayed and idolized in some fanfic communities – characters, such as Draco Malfoy, that she considered “bad”.

I guess what I’m getting at, is although the many, many fanfiction writers are building off of Rowling’s world, and by proxy, her voice as an author, is it still her voice that comes through such works? Is she the sole intellectual owner anymore, when combined with so many other’s thoughts and words?

Bloody brilliant article.