Science-Fiction: Defining a Sprawling Genre.

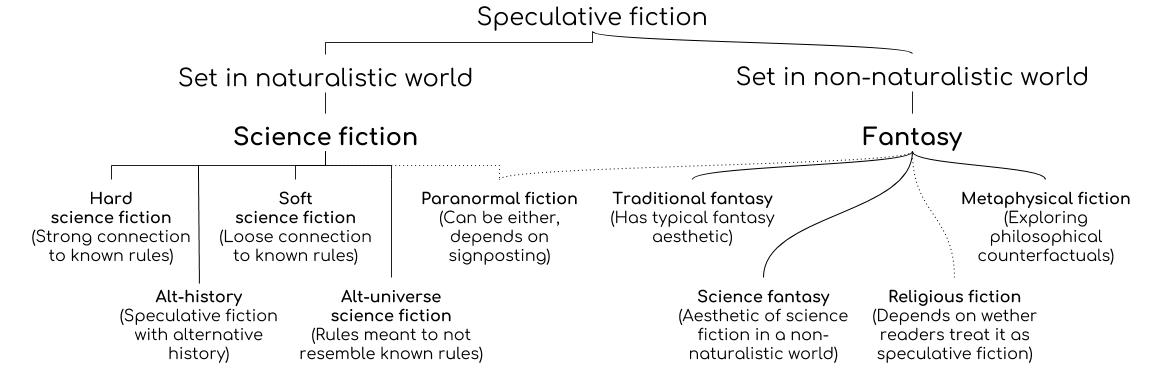

In 1987, a name was finally given to one of the fastest growing genres of fiction. This genre has roots in early 19th century works such as Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818), or The Last Man by the same (1826). Some place the origins of this genre even further in the past, holding aloft The Chemical Wedding by Johann Valentin Andreae (1616). Regardless of the origin, this: genre became known as speculative fiction, a catch-all used not only for science-fiction and fantasy, but for all the smaller genres that overlap them dystopia, horror, alternate history.

Raymond M. Coulombe, one-time editor of Quantum Muse, said:

“What is Speculative Fiction? The classic answer is that it’s the fiction of ‘what if?’ What if we had a time machine? What if we had faster than light travel? What if there was a codified reliable system of magick? What if we had honest government? For me, that is a nice place to start, and whole careers have been made writing nothing but ‘what if?’ stories. Writers could do worse. Sadly, many do.”

However, speculative fiction is only the massive umbrella under which hides our main topic — science fiction. According to Forbes, science-fiction has doubled in sales and popularity since 2010, the culmination of a 60+ year rise. Per year, it is a $590.2 million dollar industry. But where did it begin?

As with so many other concepts, beliefs, and advances, modern science fiction was brought to life in the culturally powerful era of the Renaissance. Before the Renaissance, works such as One Thousand and One Nights (late 1200’s, approximately) and The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter (late 9th century) described marvels and stories of otherworldly events. However, while these tales fit under the umbrella of speculative fiction, they relied on magic to explain events rather than science.

It is fitting, then, that the genre most related to technological advancement and knowledge would come in an era of inventions and speculations. Around the time Galileo was pushing his theories about the cosmos (and being hounded by the Catholic Church for doing so) Johannes Kepler was writing Somnium (1634). Margret Cavendish wrote The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing-World (1666) the story of a young woman stumbling upon an alternate world hidden in the arctic around the same time. Though these works certainly fit the description, they are really the prototype of the science-fiction we see today.

Evolution

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was not the first story about corpses brought back from the dead or cadavers imbued with otherworldly power, but it was the first to frame it in a scientific mold. Soon after came Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea (1870), influential not for its focus on space or alternate realities, but for its detailed focus on contemporary scientific thought and process. In the end of the novel, however, Verne toes the line between modern science-fiction and reality; a giant squid attacks, and though this was at the extreme edge of reality at the time, (squids were still shrouded in myth and legend) it’s appearance helps cement the entire novel in the annals of science-fiction history.

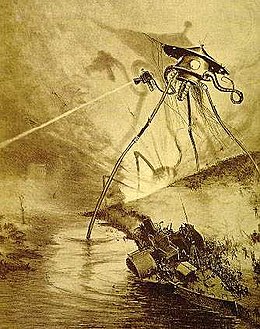

In 1898, H. G. Well’s The War of the Worlds elevated the genre to a level that is easily recognizable today; it tells the story of an invasion by aliens from the dark side of Mars. In it, the aliens are foreign, their machines and culture inscrutable, their weapons beyond imagination. War of the Worlds is, in many ways, a mold for modern science-fiction. Around this same time, the desire for a life away from the technology and machinations of the Industrial Revolution prompted works like News from Nowhere (1890), in which there is a pastoral, rural utopia lacking in machines and industrial complexes.

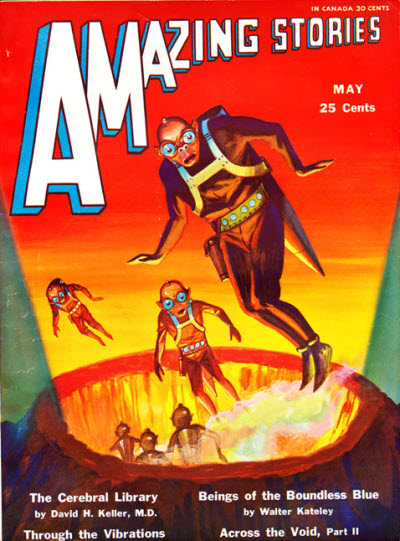

In 1926, Hugo Gernsback founded a publication called Amazing Stories, in which he began to heavily feature works by Verne, Edgar Allen Poe, and H. G. Wells. Gernsback was a professional publisher by this time, and as his publications grew in number, so did interest in science-fiction. By 1934, with the creation of the Science Fiction League, a nationwide organization comprised of young, eager science-fiction fans, the genre skyrocketed in popularity and diversity.

It is during the formative years of Amazing Stories that we can look back and see the stirrings of evolution. Already the genre was growing and changing into something that has existed to this day- a divide between hard and soft science-fiction. John W. Campbell Jr., editor of Amazing Stories from 1937-1971, was famous for his laser focus on accurate scientific research, terminology, and information. As a man with a B.S. in Physics, this is hardly surprising. There is a wide consensus that these early years of Campbell’s reign at Amazing Stories were the fist in a golden age of science-fiction

Around this time, publications out of Soviet Russia influenced other works, namely George Orwell’s 1984, published in 1949. 1984 is considered almost universally to be a titan in the genre.

After World War II, the advent of two new publications continued science-fiction’s triumphant march. The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (1949) and Galaxy Science Fiction (1950) both are heavily responsible for the continued popularity of science fiction. It is during this time, and into the 1960’s and early 1970’s that the genre was dominated by the like of Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and yes- Arthur C. Clarke. It is also during this period that science fiction and fantasy began to really break away from each other and form into separate branches on the tree of literature.

By the 1970’s, a new force was sweeping through the genre, led by authors like Harlan Ellison. During this time, many novels were published that had less focus on technological accuracy and more on the social and cultural aspects of science fiction and tales set in the near-future.

While it is an influential genre, it is also massive, and has split into two main categories: hard science-fiction, and soft science-fiction. Both have their fans and detractors.

Hard Sci-Fi

Hard science-fiction is rooted in fact, in physics and chemistry, biology and mathematics. It is thoroughly grounded in reality, or at least, the modern understanding of reality. Often, its authors hold extensive degrees in these disciplines, and write from that knowledge. In hard sci-fi, the reader is likely to be introduced to real-world concepts such as string theory, quantum mechanics, or the complicated nature of interstellar travel. For some, this is part of the appeal. They enjoy knowing that the story is rooted in fact. For others, the strict focus on realistic concepts distracts from the story or — horror of horrors — bores them.

Some of the most famous authors and novels fall into this genre.

Ringworld (1970)

Larry Niven’s Ringworld is a shining example of influential hard sci-fi literature. Not only is the image on the cover familiar to players of the groundbreaking series Halo, it was written by an author with a background in hard sciences — Larry Niven graduated from Washburn University with a B.A. in Mathematics.

In it, astronauts and aliens discover an artificial world shaped like a ring and built around a miniature sun (Halo players will be intimately familiar with the concept). The novel is extremely rational and rooted in fundamental science; in fact, after its release fans found a flaw in the design of the ringworld, prompting Niven to re-address the mechanics of his creation in a sequel called The Ringworld Engineers.

The Martian (2011)

Fans of Matt Damon and science-fiction in general might recognize this title.

The story follows the plight of an astronaut left stranded on the surface of Mars, and his attempts to survive on the harsh surface until rescue can arrive.

The film adaptation remained faithful to the novel, addressing concepts such as hydroponics, spaceflight propulsion and planning, and life in a hostile ecosystem.

The film itself grossed $630.2 million worldwide, a huge success and the largest film Fox released in 2015.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

To this day, 2001: A Space Odyssey is upheld as a masterpiece of speculative fiction. Arthur C. Clarke is considered one of the most prolific and influential authors in the genre, and with such other titles as Childhood’s End (1953) and The City and The Stars (1956), it is easy to see why.

Another novel that was adapted to film, 2001 focuses on the idea of intelligent life being “seeded” by other civilizations, and on mankind’s attempt to understand and meet with these civilizations. In it, many themes are addressed: the peril of nuclear war, A.I., and evolution, to name just a few. This novel makes use of the timeline of human evolution, real risks and rewards concerning the use and development of A.I., and the difficulties of interstellar travel.

Soft Sci-Fi

By contrast, soft science fiction deals with concepts that are more nebulous and difficult to define; politics, society, and psychology. Soft sci-fi novels tend to focus less on gritty realism and more on crafting interesting societies, stories, and characters. For this reason, most dystopian and utopian novels fall under this category.

This style appeals to readers who are looking for engaging worldbuilding or intricate storylines, and don’t mind the occasional duex ex machina handwaving to explain away some of the less scientific details.

Arguably, soft science-fiction has proven to be the more compelling and popular version; the following titles will likely sound familiar.

Dune (1965)

Utterly groundbreaking, Dune was written by journalist and photographer Frank Herbert (note the lack of a background in the hard sciences). The first in a series that would ultimately span six novels and 839,000 words, Dune has won numerous literary awards and stands as sterling example of science-fiction in general, and soft sci-fi in particular.

In it, Frank Herbert created a galaxy wide civilization made up of several Houses (powerful families) who owe allegiance to a central authority, and a complex web of conflicts between two of the more powerful houses over a harsh, deadly desert planet called Arrakis.

Herbert ignores some of the more complex nuances of spaceflight and computation, introducing a group of people called Guild Navigators, beings who ingest a rare and powerful drug that allows them to safely plot courses through space.

Dune also introduces complex social and political hierarchies, sects of mysterious religious cults, outlandish lifeforms, and philosophical ideas not often explored in hard sci-fi works. Together, these culminate in what can be called a proto Game of Thrones; similar concepts and themes, set against the backdrop of a galactic playground.

1984 (1949)

1984, written by George Orwell, popularized the concepts of government surveillance, thought-crime (and thought-police) and totalitarian government. In fact, many terms and concepts find their origins through the work; “Orwellian”, “2=2+5”, and “Big Brother.”

The novel focuses on the formation of three superstates after WWII, all of which fight in an endless war for control of the ideology of their citizens. The novel has been scrutinized and analyzed for decades, and again, focuses more on the “soft” sciences.

For example, it is revealed in the novel that nuclear weapons were used by the three major superstates after WWII, but the specifics of fallout and global famine that would occur are not discussed. Instead, Orwell focused on the dystopian nature of a totalitarian superstate obsessed with controlling its population.

Star Wars (1977)

Dozens of books. Rapidly approaching a dozen films. Star Wars has, of course, captivated the hearts of millions of fans, a franchise that has only grown in the 41 years since it’s creation. Fans will know immediately why it falls into the soft sci-fi category: hyperdrives, lightsabers, the Force. All are thoroughly un-scientific concepts.

Of course, that doesn’t make it any less popular; in fact, Star Wars is the most successful work on this list by leaps and bounds. Grossing over $7.5 billion at the box office alone, not counting the vast literary fanbase, Star Wars has become one of fiction’s most popular universes.

Mixing It Up

There are novels that push the envelope though, as there always are. These works bring the wings of the genre together into a blend that, when done properly, is phenomenal.

Ender’s Game (1985)

Fans of Orson Scott Card will no doubt recognize one of his most popular novels. Ender’s Game is the story of children recruited by the military of a united Earth, in hopes that they will be able to protect the planet from a coming alien invasion. In it, real-world concepts such as zero-gravity, interstellar travel, and military discipline blend with a tale of aliens, command, and sacrifice. The first in an expansive series, fans will have plenty of opportunities to return to the universe Card has created.

Bringing together elements from two beloved areas of the genre, it is not surprising that Ender’s Game was a massive success.

Major Themes

Over the decades, several primary themes have grown in popularity and frequency and appear in both hard and soft sci-fi.

Utopias and Dystopias- While the latter has seen a wild increase in popularity recently, utopian science fiction is not without its merit or recognizable titles. Novels like The Giver (1993) play with the ideas of utopia, though The Giver plays subtly with both. Dystopian novels take on the idea of oppressive or restrictive government, and often even the complete lack of government. Utopias take the opposite approach. These stories envision the perfect world, with peaceful governments, safety, and equality. A core reason dystopias are more popular with both writers and readers is that they are, by their very nature, absolutely dripping with tension and conflict.

Alien Encounters- A pillar of the genre and one that hardly needs explanation. Alien encounters are perhaps the most prevalent type of tale in the genre, as they allow authors an amount of creative and literary freedom most other genres restrict. This type also appears in all the various branches of science-fiction. From stories of first contact, to peaceful coexistence, to savage warfare and colonization, these tales are common.

Space Travel- Another staple of the genre, one that has proven both necessary and entwined with several other themes. The number of science fiction novels that rely on spaceflight or interstellar travel is immense. Though the genre did not start out with this theme, it has certainly found a place here.

Time Travel- While less prevalent than some of the other themes, stories of time travel (both forward and backward) have also found a niche in this genre. Whether that involves novels such as H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine (1895) or one of Stephen King’s lesser known works 11/22/63 (2011), time travel novels are popular among many science-fiction fans. Indeed, a number of famous movies fall into this sub-genre, such as Terminator (1984) and Back to the Future (1985).

Advanced Technology- Many novels, especially those concerned with alien encounters or spaceflight, make a point of the advanced technology being used or developed. Examples are endless. Dune, Star Wars, Artemis (2017), Jurassic Park (1990). The list goes on and on. Whether these novels deal with advanced terraforming techniques or futuristic medical capabilities, the possibilities are infinite.

Alternate History and the Parallel Universe- These novels deal often with “what-ifs”: for example, Clash of Eagles (2015) describes a world in which the Roman Empire never fell, and instead crosses the ocean in the year 1218 AD, meeting and ultimately waging war with the native tribes on the North American continent. Another famous example is The Man in The High Castle (1962), which shows a world where the Axis Powers won WWII. In it, Germany and Japan now rule the world — and bite at each other as they do so.

Steampunk- Truly a sub-genre all its own, steampunk novels take the reader to a world where steam technology has either never been rendered obsolete, or where it is fully integrated into the society. Often, these works are set in the American Midwest, Victorian England, or in a world entirely of the author’s creation. Novels that fall into this theme include Infernal Devices (1987) and The Time Machine (1895). Even to the uninitiated, steampunk illustrations are often instantly recognizable. For a tiny sub-genre of a massive branch of literature, steampunk has certainly made an impression.

One Genre, One Fanbase

Science-fiction has been rising rapidly for nearly a century, and has roots that are even older. Modern trends are taking the genre to places never explored before, from virtual reality to A.I. As technology advances, the potential for new and groundbreaking novels only becomes more and more expansive.

In the end, regardless of which wing you prefer, which authors or novels you enjoy, sci-fi has a place for all of us. Every year, dozens of new novels are published, and the genre is ever expanding. Rest assured, science-fiction isn’t going anywhere.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Wow! This is a very well written, thoughtful and detailed article. I love Sci Fi and Fantasy and I will definitely revisit this as I continue to write and explore these genres! Excellent and informative article!

Thanks Sean. Glad you enjoyed it!

Good stuff. I love SF. And social research.

Thank you!

My late uncle was a professor of physics in California. His ‘den’ was wall to wall books and they were mainly Sci Fi. He told me that these books were where he got his theories from.

Jules Verne in the end of 19th century was predicting submarine’s structure and functionality to the incredible level of detail for example. However we shouldn’t be led to believe that everything we see in sci-fi films or books will come to exist.

Far from it.

Dystopian and utopian writers were imagining all types of societies for centuries and none of their predictions ever came true to the full. Designers and visionaries can think of many technological advancements but whether they become real depends not only on the level of technological progress but also on very basic predispositions: purpose and resources. From this perspective sci-fi films like “Interstellar” can actually be pretty dangerous because they lead to believe into inevitability of interstellar travel and eventual disposal of Earth.

This may or may not happen for another few hundred years, while climate change and all associated problems are happening right now right here with this generation of humans.

That has been my dream for a long time. A room filled with a big desk, comfy armchairs, and bookshelves stacked ceiling high all around.

The same applies when designing human computer interactions too.

Science Fiction is a very useful tool to prophesy the past…

What?

Isaac Asimov and Arthur C Clarke are the best science-fiction witers of all times. They both possessed the entire qualities required for this genre. Clarke was more hard-sci-fi, but gifted with a immense poetry and imagination; Asimov,though phantasizing a little,had so much knowledge and literary abilities, that was deliciously readable.

I have to disagree. Much that the teenage me loved Asimov’s science fiction, these days I find it all but unreadable.

Asimov was a distinguished scientist in his own right, and had a fabulous science fiction imagination, but his writing sucked. In particular, his characters are so flat, wooden and stereotyped they make those of Agatha Christie look positively complex.

The best science fiction is about character.

The best science fiction tends to be about us today, but with an alternative setting.

The best of it is about now, even if it says it is set in the future. It’s purpose is no different than any other fiction, it is commenting on the human condition.

Can be. The human condition is not the only thing that is interesting though. And it’s very distracting when the science just doesn’t work.

One thing that really annoys me is when authors take a perfectly good SF setting and later decide to randomly introduce something else they’ve seen in SF. Often psychic powers. Nothing wrong with with psychic powers as a SF subject (though frankly they’re on the implausible end) but why tack it on to a plausible story featuring, say, a generation ship? Isn’t there enough excitement in the first idea? Obviously you can totally reinvent a whole universe with both psychic powers and generation ships, but it irritates me when a story has just two non-real-world components.

Interesting article!

Thank you!

“science-fiction” is just a catch-all phrase for speculative fiction

I read a lot of sci-fi, all the way from junk/pulp through to the serious hard-science stuff and the only complaint I ever have about any individual book is if it’s badly written.

I’m much the same way. Very forgiving of most things, as long as the premise is interesting or the characters connectable.

great!

Thank you!

A good essay. I recommended it to a colleague who teaches literature and likes to refer to science fiction in his courses.

I’m honored you thought so highly of it. Thank you so much, and for your help with the editing phase.

Reading currently every Science Fiction anthology I own, just before I will chuck them all out (but the Stanislaw Lem/Robert Sheckley/ Ray Bradbury/ William Gibson/ Robert Silverberg stay !) Some of them, specifically from the 50-60, are truly awful, but you can still find some hidden gems. And it is interesting how a specific subject of science (which is still Fiction) changes. Take the example of the recent “Lock in”. I was immediately reminded of the old book “The ship who sang”. Or how our relationship with AI changes.

Sounds interesting… I’ll be sure to check those out!

I loved the article.

Thank you so much!

I define science fiction as fiction about science. By that definition, any writer of science fiction must do the proper research to make a scientific meme as credible as possible. Since I write both science fiction and horror, I concentrate on those aspects of the science which makes the scenario of human interaction with science as plausible as possible. For example, I allow for light travel, but not faster than light travel. The only exception to this rule is with Star Trek, since the science hums in the background while the human interaction with it is not the primary consideration. The science is deus ex machina to the scene.

Exactly! Much of what you said fits into the “hard” sci-fi sub-genre. The dues ex machina of Star Trek, though, definitely fits into “soft” sci-fi.

“I define science fiction as fiction about science.”

And you have every right to do so. But many would not.

Your definition might instead be regarded as describing a sub-genre, that of ‘hard’ science fiction. As a catch-all for the genre as a whole, I think I prefer ‘speculative fiction’, although it is perhaps open to accusations of sounding pretentious.

Bad science doesn’t bother me – especially as I love reading old 1960s pulps that have been utterly disproved even on a simple domestic, every day level by what we’ve learned and invented since then. The story is the thing.

I’m confused. You said that the name ‘science fiction’ was coined in 1987 and then you say that the Science Fiction League came about in 1934. Are you sure that you don’t mean 1897?

Oops. I didn’t read that right. Speculative fiction, my bad.

Startled me there for a moment!

All of technology is a manifestation of desire. The superpowers of mythical gods and heroes, flying, long distance communication etc., are the real drivers of invention. Well before sci-fi mythology planted the seeds.

Indeed, mythology contains several of the characteristics and human desires found in today’s sci-fi

I’ve always wondered if there is a precise definition of science fiction. Is it time sensitive?

The definition of science fiction and fantasy are very fluid and almost up to the reader. But broadly for science fiction there has to be a consistent application of real world physics and consistent hypothetical physics. So faster than light can be scifi so long as it is sort of consistent and has some trace of reality.

But even then you will get a huge amount many will consider fantasy fitting that definition.

In terms of time, galaxies far far away and long time ago tend to be out.

Works based around the desire to leave the growing cities predate 1890 by quite a bit. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1852 novel “The Blithedale Romance” was a fictionalized representation of an actual attempt at creating an agrarian utopia at Brook Farm, Massachusetts, in the 1840s. Such attempts were heavily influenced by Transcendentalism, and emphasized reliance on the self and human relations rather than technology; a sentiment mirrored in later classic science-fiction stories like Ray Bradbury’s “The Veldt.” (1950).

What a great article. You really know your stuff!

Thank you! You’re too kind!

I love Sci-Fi, this is so intriguing and informative!!

It’s a great genre! & thanks!

I adore how you’ve done a neat walk-through and dissection of this genre. A really interesting read 🙂

Thanks so much!

Nice little overview of a complex genre, thanks for sharing.

Thank you! 🙂

A very comprehensive look at fiction writing, I will definitely be re-reading this article sometime in the future in reference to science-fiction and fantasy works, excellent article!

Thank you!

This is a really comprehensive and informational article!

Thank you!

Great lay out of the genre. Thank you! Good references for the sub categories. All in all, excellent!

Thanks so much!

Great article on science fiction. Informative and interesting.

Thank you!

There has been a lot of postcol science fiction writing, that indeed writes back to the eurocentric vision of science fiction.

Astonishing coverage of the classics in this genre. I was particularly taken aback by the Weir novel and film adaptation. In a way, it alone embodies all the major science fiction themes you list. Though I haven’t read it or watched the film, I can see how space travel and time travel could easily play into the planetary maroon plot. Many angles to this topic.

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed it!

Very interesting and comprehensive! Thank you.

The genres may be better defined now; I always tend to remember the blurred lines and the exceptions. For example, Conan met an alien from space in one of his early stories, “Tower of the Elephant”; and later, there was a crashed spaceship in one of the kingdoms of Mystara, from the early Dungeons and Dragons sourcebooks.

Thank you!

Thank you for this wonderful and informative article! Just from reading this you know far more than me.

I personally like science fiction because of its speculative nature and the questions it poses on us – because of this my favourite film would have to be Arrival.

Thank you very much!

You should be startled. The term “speculative fiction” was used in the 1940’s by Robert Heinlein, but there are references to earlier use of the term going back to the late 19th century. In the 1960’s and 70’s the designation SF was commonly used as an umbrella that could mean speculative fiction as well as science fiction and science fantasy. The terms were frequently discussed, defined and redefined by writers and critics such as Asimov, Harlan Ellison, Judith Merrill, Algys Budrys, Damon Knight, Norman Spinrad, et al. A look at the editorial and book review pages in magazines such as Astounding (renamed Analog), Galaxy, Worlds of If, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and Asimov’s from the 40’s through the early 80’s will see the term was present way earlier than 1987. The use of that date (without quoting a source by the way) almost kept me from enjoying an otherwise quite interesting piece.

Have to agree with the couple of people who suggest that the term “speculative fiction” is older than you’re initially suggesting. But I do really like the way that you break down sub-genres and the major topics within them. Suggestion for future consideration if writing about SF history or genres – think about “space opera” as a major sub-genre. Lots of what you have in the other sub-genres here would fit well with that, too, and it was a big influence in the 1930s and 40s.

I’ve just recently started to discover the gift that is sci-fi. As someone who studies literature I always love to see an analysis like this. Great article!!