Serena and the Power of Collaborative Indie Game Development

Anger can destroy.

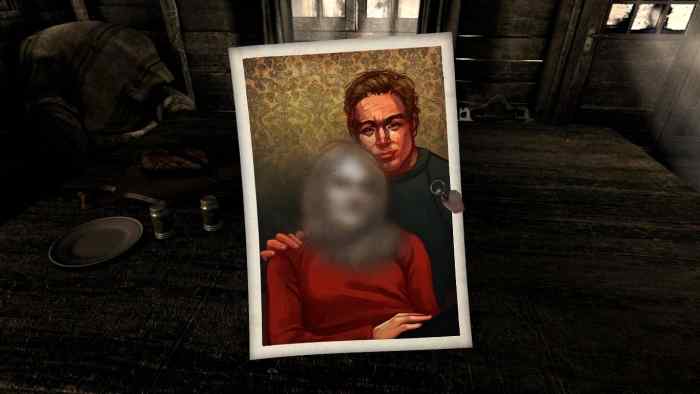

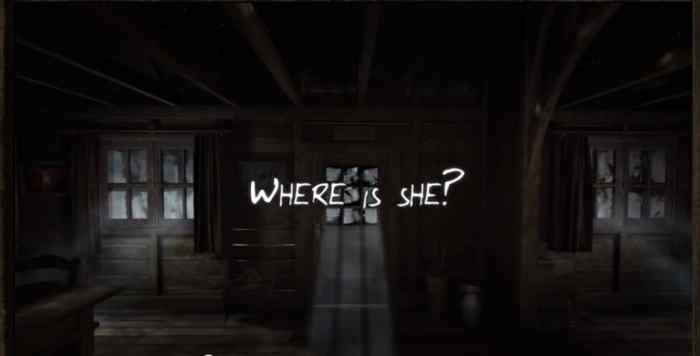

In Serena, the main character’s pent-up rage leads to the destruction of his marriage. On the surface, the game is about a man wandering through a getaway cabin as he struggles to remember his missing wife, Serena. Things in the cabin evoke memories of their relationship, and the unnamed protagonist comes to a disturbing realization about the ruination that his anger has caused.

But anger can also create.

When a dramatic turn of events threatened the comeback of the adventure game genre, which has been slowly dying for some time now, Agustín Cordes, along with dozens of indie adventure game fans and designers, reacted to the negativity by creating Serena. Rather than provoking more in-fighting that would further dethrone the genre, they decided to make a new game with hopes of reviving the adventure gaming scene. 1

The Backstory

Sparks flew in November 2013 when Replay Games founder Paul Trowe began openly criticizing others in the indie adventure game scene. 2 After a successful 2012 Kickstarter, which enabled Trowe and the company to bring back the ever-popular Leisure Suit Larry, he began publicly flinging insults at former business partners and certain Kickstarters. 3 Some accused him of “trolling” the scene, some called him downright rude, and others felt that he was merely a less-than-tactful game maker expressing his qualms to the public. Any way you slice it, he hurt the feelings of gamers who were optimistic for a comeback.

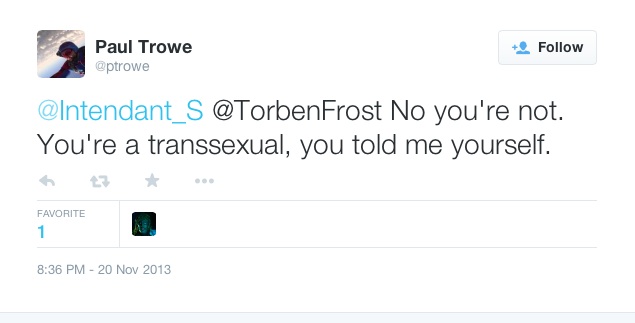

Trowe’s online antics climaxed in November 2013 when he publicly identified Serena Nelson, a former Leisure Suit Larry volunteer who had been critical of him, as being transsexual. 4 Nelson acknowledged that this was not a secret to everyone but was still furious, considering the tweet to be an unwanted outing. 5 Though Trowe later tweeted an apology to Nelson, who had come to be known as the “Hero of the Adventure Game Revival Movement” through her advocacy for adventure game Kickstarters, the damage was already done. 6 Trowe’s words were painful for people like Agustín Cordes, who sensed that the entrepreneur’s bullying had put a damper on the genre’s much-needed revival.

“I saw many people hurt by Trowe and [sensed] a general feeling of discomfort in the adventure game community,” Cordes told Kotaku.com’s Stephen Totilo in an email interview last year, “”My reasoning was ‘OK, let’s do something together to counterbalance such awfulness.'” 7

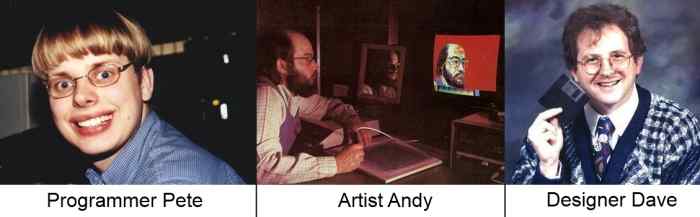

Thus, Serena, named after Serena Nelson herself, was born. The game was released in January 2o14 and was open sourced shortly after. More than 40 adventure game designers and fans contributed to the project, including ex-volunteers from the Leisure Suit Larry remake project, as well as talents from renowned indie game companies like Senscape, CBE Software, Infamous Quests, and others. 8

Indie game developer Josh Mandel, who originally voiced King Graham in the King’s Quest series and who voices Serena‘s protagonist, called the project “the greatest gesture any game designer could make towards a fan” and “the most enormous love-and-condolences note in adventure gaming history.” 9

Indeed, Serena is a grim point-and-click adventure story that is truly representative of “the venerable [indie adventure game] genre and its passionate community.” 10 It exhibits the power of hope and collaboration.

Serena: A Lovecraftian Horror Adventure

Serena is essentially a one-room game with story breadcrumbs scattered about for the player to click on. Players embark on the adventure in first-person as an unreliable narrator with laser-guided amnesia who recalls that something has happened to his wife to cause her disappearance but does not remember much else. The player can interact multiple times with the comb or the dining room table or any of the objects throughout the cabin to hear the character say different things about them. Though the voice acting is hokey at times, the developers spared no effort in creating a great deal of feedback for each item, breaking free of the typical, static way of having one response per object.

The game tells a darkly brilliant story that players must uncover on their own using the very simple mode of gameplay. Though there are a few moments of “purple prose,” prose so flowery or excessive that it draws unnecessary attention to itself, much of what the protagonist says is tastefully subtle in its way of slowly revealing the couple’s situation. Players quickly realize that things are not at all what they seem.

One powerful example has to do with a collection of dead leaves and flowers hidden somewhere in the cabin, about which the character says, “They say [plants] are alive…if they are, it must be a horrible existence – confined in their own silent, dark world…” 11 Similarly, the protagonist seems to be confined to his own “silent, dark world” as he wanders about a dark, dusty cabin waiting for a woman who may never come.

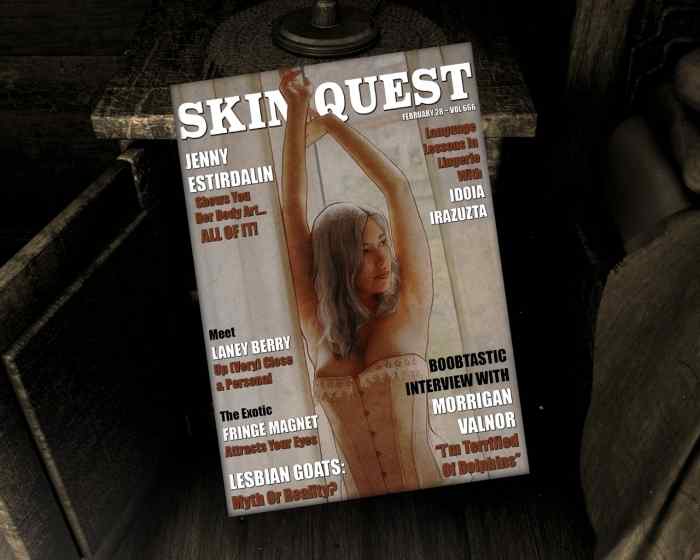

Rather than relying on shocking images and cheap jump scares to frighten the player, Serena‘s merits as a horror adventure lie in the cabin’s unsettling ambiance. Eerie music, darkness, the ticking of an out-of-sync cuckoo clock, and dust raining on everything within the cabin make up much of the game’s sinister visual and auditory aesthetics. There are a number of creepy Easter eggs to be found throughout the cabin, as well.

But what makes Serena truly Lovecraftian, truly horrifying, is the story’s shocking conclusion (Fear not! There are no spoilers here). Lovecraftian horror, a term and definition derived from the tropes that characterize the fiction of horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, emphasizes the cosmic horror of the unknown and the unknowable. Though gore and other shocking elements may be included in such a story, these are not the focus. Almost entirely devoid of gore, Serena pulls off a truly Lovecraftian ending, one that is not so obviously resolved. Players may believe that they fully understand the conclusion; however, nothing about the game’s story is truly knowable, leaving players questioning everything that they have just experienced.

Strength in Numbers: Collaboration and the Future of Indie Gaming

Based on Serena’s success as the largest, possibly even the first, project of its kind, 12 it seems that collaborative game development has the potential to become a powerful entity in the future of indie games. Amidst concerns about the “indie games bubble” (oversaturation of the indie game market), many in the scene believe that the future of indie game development depends on collaboration.

As big name studios continue to use independent contractors to work on their games rather than hiring resident designers, the market for indie game developers, colloquially labeled “indies,” has become more saturated. 13 Rather than attempt to go at it alone in the crowded sector, those concerned with the future of indie gaming are suggesting that indie game makers work together to create, market, and sell games. Though (unfortunately) there are struggles associated with each positive aspect of collaboration, there are three major benefits that back this suggestion.

1. Unrestrained Creative Vision

Collaborating with other like-minded developers can allow indies to share and improve their creative ideas, rather than being limited by the requirements of a large development studio. Indies can meet other game makers with similar visions through resources like online gaming forums and game development meetups. Although working alone may seem more freeing, collaboration is ideal because it allows indies to work off of each other’s ideas to grow their visions into better, even more creative games.

Collaborating with other like-minded developers can allow indies to share and improve their creative ideas, rather than being limited by the requirements of a large development studio. Indies can meet other game makers with similar visions through resources like online gaming forums and game development meetups. Although working alone may seem more freeing, collaboration is ideal because it allows indies to work off of each other’s ideas to grow their visions into better, even more creative games.

The Struggle: Unfortunately, it can be difficult to find the perfect partners. Though indies who collaborate don’t have to bow down to the needs of a large company, they do need to find others with whom they share creative goals.

2. Flexibility

Collaborating with other indies on a project-by-project basis actually provides more stability than working for large gaming companies, which often let workers go as large projects end, with the added bonus of flexibility. Indies who work together can function with a higher level of autonomy, as they are not subject to the desires of an industry giant, and they are not stuck toiling over a game on their own. Jobs can be shared among partners, indies can make their own rules and schedules, and developers can even hold down separate, more stable jobs on the side, if they so choose.

The Struggle: Though collaboration allows indies to work on their own terms, there is no certainty in the success of their projects. While working for a large company may inevitably lead to eventual, unfortunate termination, contractors will certainly be paid for their work, regardless of how well or how poorly the game does on the market. On the other hand, indies who forego contracting for large companies in favor of flexibility often need to hold down additional jobs in order to get by.

3. Networking and Marketing Opportunities

Perhaps the greatest benefit of indie collaboration is the amount of networking and marketing opportunities that exist for those who work together. Indies who collaborate receive “increased access to personal networks,” 14 as well as more opportunities to market their products. Online resources like the Indie Game Developer Network, a network that brings developers together, and Develteam, a collaboration-based social network for indies, as well as offline resources like indie gaming conventions, serve to link up indies who are looking to work together or to gain insight from fellow game makers. Conventions, trade shows, and game bundles, all of which are planned and executed with collaboration in mind, can also assist developers in marketing their products to studios and gamers.

The Struggle: On October 29, 2013, Steam alone accepted 100 games for publishing from their Greenlight system. 15 While collaboration presents more opportunities for networking and marketing, there are so many indie games out there that it can be tough to get noticed, a struggle that developers don’t face when working for big-name studios. This is perhaps the most pressing concern that indie game makers face in the market.

Whether they’re reacting to a personal situation, as was the case for those who worked on Serena, trying to get noticed in the industry, or working on games as a side project, there’s no denying the power that developers have when they collaborate. Together, game makers are mega, as partnering up offers them unbridled opportunities to exercise creative vision, to function with more autonomy, and to network and market their projects with greater chances of success. Serena‘s triumph as a collaboratively built horror adventure that has received overwhelmingly positive reviews among players and critics alike is only the beginning of what working together can offer indies and the gaming industry.

Serena is compatible with Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux and is available for free on Steam.

“Individually, we are one drop. Together, we are an ocean.” -Ryunosuke Satoro

Works Cited

- Stephen Totilo, “A Disturbing Gift for Fans of Adventure Games.” Kotaku.com, (Jan. 2014) ↩

- Stephen Totilo, “A Disturbing Gift for Fans of Adventure Games.” Kotaku.com, (Jan. 2014) ↩

- Stephen Totilo, “A Disturbing Gift for Fans of Adventure Games.” Kotaku.com, (Jan. 2014) ↩

- Stephen Totilo, “A Disturbing Gift for Fans of Adventure Games.” Kotaku.com, (Jan. 2014) ↩

- Stephen Totilo, “A Disturbing Gift for Fans of Adventure Games.” Kotaku.com, (Jan. 2014) ↩

- Stephen Totilo, “A Disturbing Gift for Fans of Adventure Games.” Kotaku.com, (Jan. 2014) ↩

- Stephen Totilo, “A Disturbing Gift for Fans of Adventure Games.” Kotaku.com, (Jan. 2014) ↩

- “Now Available on Steam- Serena.” Store.Steampowered.com, (Jan. 2014). ↩

- Stephen Totilo, “A Disturbing Gift for Fans of Adventure Games.” Kotaku.com, (Jan. 2014) ↩

- “Now Available on Steam- Serena.” Store.Steampowered.com, (Jan. 2014). ↩

- Cordes, Agustín, Pablo Forsolloza, Simo Sakari Aaltonen, Frederick Olsen, and Troels Pleimert. “Serena.” Written and designed by Agustín Cordes. Senscape, 2014. ↩

- “Now Available on Steam- Serena.” Store.Steampowered.com, (Jan. 2014). ↩

- Ben Serviss, “Together We Are Mega: The Collaborative Future of Indie Game Development.” Gamasutra.com, (March 2014). ↩

- Ben Serviss, “Together We Are Mega: The Collaborative Future of Indie Game Development.” Gamasutra.com, (March 2014). ↩

- Jeff Vogel, “Marketing, Dumb Luck, and the Popping of the Indie Bubble.” Gamasutra.com, (Nov, 2013). ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I was scared for most of the game in case something jumped out. Especially at the random clock chimes, that really freaked me out.

Lovely read, and very good story in Serena.

I think the music in the background is really what makes this game for me.

The atmosphere in this game made me so uncomfortable. Every time I finish inspecting something, I feel like something is going to be behind me. I couldn’t continue playing.

I played this game and when i say that dead body i was like fuck this im quiting so i quit

Took me awhile to figure this game out. I was pretty bored and was stuck clicking things and not progressing the story until I realized I had to reexamine the photo, things got darker from there. Then I started to appreciate the mood that the music and tone of the story narration had. From Sentimental, to Angry, to Sorrowful.

I feel little cheated about the ending, is this just the bad ending or the definitive ending? I am drawn to the book shelf, the poetry, the photo of the children and the the painting of a shadowy figure and what of the blood stain growing near the table? Stories of the Fae, and the Necronomicon.

I think collaboration is the easiest way to get your name out – especially if you’re just starting out in the industry and have minimal experience.

It’s nice to read that a community got together to make a game in response to a fan’s uncomfortable experience. I don’t play too many indie games, but this was a lovely read. Thanks!

Really fun game I played took me 20 min to beat

This feels like something out of a Stephen King novel.

More interactive story like this.

This game takes all sorts of dark turns.

Serena is my daughter’s name. I must play! (maybe not with her…)

Looks creepy.

It is, all the scenario looks dark and depressing for that same reason.

I went bananas after playing and touching everything for 2 hours and didn’t knew what to do.

Most boring game to watch and play ever . . . but it’s free!(still not worth it)

indies want videogames to be interactive movie blogs…

Great game. I really enjoyed playing it.

I’d like to know what percentage of people actually play this game. I started it up, clicked on everything in the room and it all did nothing, gave up…

I love dramatic point and click adventures!

Enjoying the game, and it’s lovely twisted nature!

I haven’t played the game but you make it sound great. I love the way that you went from synopsis to analysis of the game and then into an analysis of the genre and working conditions of designers. A very good read!

I played Serena before I knew any of its backstory. I’m glad you gave a concise history. It really contextualizes the game, and makes it even more impressive.

Like you said, the voice acting is a bit hokey, but the narrative is phenomenal. It really succeeds as a digital narrative, allowing the player to explore at their own pace without losing the quality of its storytelling. If this is the result of indie game-making collaboration, then I’m excited to see what else the industry has to offer. Removing Serena from the profit-driven industry and creating it for an artistic and striking purpose truly allowed the game to flourish. It shows how much of an impact a video game can make; games like this are defining the future of the indie industry.

Wow, I love indie horror games, especially ones with Lovecraftian elements, so thanks for bringing up Serena, which I’ve never heard of. You also make great points about the struggles of indie gaming. The real life Serena Nelson being targeted was horrific, and it’s good that the game was named after her.

I use Linux and I’m very happy when most games run on this platform.