The Shape Of The Action Hero

Before we look at the action hero, it is important to understand the nature of the action film. To do so we must look back into the roots of Cinema itself. We start with the Train Pulling Into The Station or its French name: L’Arivee d’un train en gare a La Ciotat (Auguste & Louis Lumière, 1895, France). A fifty second documentary that shocked the first cinema audience. They witnessed not only the birth of cinema, but also an oncoming train that seemed intent on bursting through the silver screen. Some must have gasped in awe at the sheer thrill of seeing the moving image. While others ran for their lives, terrified at the prospect of being run over.

The boast of the cinematograph had been its ability to capture and project life in action, as opposed to the photograph; a still image of life. One could argue that action cinema was the first genre of film. Especially as the Lumière brothers had marketed their cinematic exhibition for the raw spectacle of its image’s movement. Today action movies are marketed to us for much of the same reason. The key difference is that what is sold to us now, is no longer raw. The spectacle is no longer caught on film purely for the sake that the images move.

Through the advent of the action hero the movement is now given a context. What we understand of the action film today obviously encompasses the following: explosions, bullets, guns and hard bodies. We are treated to polarising narratives of good vs. evil. With a hero who rises to an occasion much out of his depth. When there is no reason he should win, he prevails through his ingrained resourcefulness. Yet the core idea behind all this is movement. It’s not just about the heroes mobility in his efforts to evade a hail of bullets. It’s also about his ability to be decisive in the choices he makes; for the action hero is no Hamlet. He knows what he needs to do, any self doubt & limitations are overcome by an indomitable spirit and a tenacity to prevail. When faced with a perilous dilemma he moves to act, he is never static nor is he passive. He takes action, for movement is at the core of his being.

The action hero is comparable to the hero of the fantasy novel. Which often tell tales of an individual who embarks on a quest to change their world. They can transcend the laws of man and nature; achieving what is out of reach for most ordinary people. Similarly the action hero can transcend the rules for they are not resigned to a destiny or fate, they actively make their own luck. For he holds a power that we lack in our own lives, for as spectators we wish to be the hero and become a force of change. The hero is the ideal we wish ourselves to be. The audience of action wants the hard body of Arnold Schwarzenegger, we want to be as daring and as agile as Jackie Chan. We want to believe we have the courage of Rocky. We want to be Clint Eastwood; submitting villains with a stone hard look. We want to believe we encompass such traits, in order to effect change in the world around us. Action movies let us live these fantasies of our ideal selves from the comfort of our seats. We watch our ideal selves unfold on the big theatre screen. When our action heroes find their lives under threat of an oncoming train: we bare the tension of it. But with a level of comfort, we know it’s not real. A benefit the terrified Lumière audience could not afford as the train closed in on them. We can take our safety for granted, for the perils that face the action hero are not really the ordeals we wish to face ourselves. Yet it’s that ability to cope with those perils, which really appeals to us as the audience of action.

The action hero is comparable to the hero of the fantasy novel. Which often tell tales of an individual who embarks on a quest to change their world. They can transcend the laws of man and nature; achieving what is out of reach for most ordinary people. Similarly the action hero can transcend the rules for they are not resigned to a destiny or fate, they actively make their own luck. For he holds a power that we lack in our own lives, for as spectators we wish to be the hero and become a force of change. The hero is the ideal we wish ourselves to be. The audience of action wants the hard body of Arnold Schwarzenegger, we want to be as daring and as agile as Jackie Chan. We want to believe we have the courage of Rocky. We want to be Clint Eastwood; submitting villains with a stone hard look. We want to believe we encompass such traits, in order to effect change in the world around us. Action movies let us live these fantasies of our ideal selves from the comfort of our seats. We watch our ideal selves unfold on the big theatre screen. When our action heroes find their lives under threat of an oncoming train: we bare the tension of it. But with a level of comfort, we know it’s not real. A benefit the terrified Lumière audience could not afford as the train closed in on them. We can take our safety for granted, for the perils that face the action hero are not really the ordeals we wish to face ourselves. Yet it’s that ability to cope with those perils, which really appeals to us as the audience of action.

The Hard Body

The focus of action cinema is on the heroes’ ability to overcome the physical object that compels him to movement, to action. At the same time the narratives of these films have encapsulated different qualities & values over the years. But the one that has remained fundamental is the focus on the hard body. This is a genre that satisfies a curiosity of the human body, something that’s addressed every day in the field of sports competitions. A boxer may forge a hard body during training and then tests his limits with another fighter. The action hero takes this a step further; his opponent is no single individual but rather his urban environment.

The focus of action cinema is on the heroes’ ability to overcome the physical object that compels him to movement, to action. At the same time the narratives of these films have encapsulated different qualities & values over the years. But the one that has remained fundamental is the focus on the hard body. This is a genre that satisfies a curiosity of the human body, something that’s addressed every day in the field of sports competitions. A boxer may forge a hard body during training and then tests his limits with another fighter. The action hero takes this a step further; his opponent is no single individual but rather his urban environment.

Douglas Fairbanks is a master of his environment; as demonstrated during the exposition of The Thief Of Baghdad (Raoul Walsh, 1924, US) where he manages to manoeuvre from space to space almost without effort. His body affords him a freedom that puts him one step ahead of the laws of his society. It’s this same body that will enable him to navigate around the perils that shall assault him later on. Fairbanks was the Jackie Chan of his time. Though the likes of Buster Keaton and Gene Kelly would prove to be the real inspiration behind a lot of Jackie Chan’s stunt work, it’s plain to see the similarity in how these free runners have engaged with their urban environments.

The action hero is undoubtedly compelled to face the perils of human invention; which range from weapons to vehicles and the very buildings they inhabit. Yet for the most part we know a bloodied John McClain is not really scaling down a building in Die Hard (John McTeirnan, 1989, US) or that Stallone hasn’t really driven a tank into a helicopter in Rambo 3 (Peter Macdonald, 1988, US). Yet we suspend our disbelief. Jackie Chan is exceptional in this regard for his reputation of performing his own stunts. A key feature of his films are the end credit out-takes, which often places focus on stunts that had failed, stunts that would often prove to be life threatening. It’s not as easy as it initially all looks, as the demand for spectacle proves to be taxing on the human body. It also serves to remind us that what we see is very much real. Chan puts us in the position of the Lumière audience to a certain extent, because we watch the spectacle with the tension of it being reality.

When Jackie Chan broke through to Hollywood he was marketed for doing his own stunts. Since then the boast of stars doing any extent of stunt work has become an effective marketing tool. For they want to sell us the spectacle of the human body, but with the tension of reality. Thus efforts are made to sell us something that is genuine.

In this era of computer generated imagery (CGI), it’s crucial to understand why the tension of reality that Chan provides has been so appealing. A CGI Spider-man leaping from building to building is outside the realms of possibility. Yet the action sequences of a Jackie Chan film illustrate what is possible within the limits of the human body. His style of action is inclusive of its audience, because it reflects a potential within all of us. If bitten by a radioactive spider we’d die of cancer. But if we practiced our kung fu as demonstrated by the Martial Art films of the 1970s; our fantasy of the hard body becomes attainable. Chan’s appeal lies in that he functions within the realm of possibility. Rocky (John G. Avildsen, 1976, US) offers a similar value within its training montage; the hero forges the hard body to fight the champion Apollo Creed. But it’s not enough; he’s a bum fighting the greatest fighter of the world. He has to make up for his short comings with his will, spirit and stamina. Thus Rocky is inclusive to his audience, by illustrating that we can make up for our weak bodies with the sheer strength of the human spirit. Once again appealing to its audience by functioning within the realm of possibility.

National Identity

National identity has played a role in shaping not only the characters of action cinema, but also in how Hollywood have tried to market their action stars.

National identity has played a role in shaping not only the characters of action cinema, but also in how Hollywood have tried to market their action stars.

Rocky is a character who champions America as being the land of opportunity. His narrative is that of the classic Hollywood ideology: the underdog overcoming adversity. His role becomes political in Rocky 4 when he fights the champion of the Soviet Union: Ivan Drago. This back and forth boxing war of attrition alludes to what would happen if the cold war ever heated up: victory for America. He goes from championing American values towards addressing a political anxiety of the time.

Sylvester Stallone once again turns to politics in Rambo 2 (George P. Cosmatos, 1985, US). During the opening expositional scenes: Rambo’s former Commander approaches him with an offer to go back to save POWs in Vietnam. Upon his agreement he asks if “we get to win this time?”, the Commander responds that this time its up to him. This takes me back to my earlier point: the hero makes his own luck. This film aims to address the humiliation the U.S. suffered as a result of losing the Vietnam War. Here the action hero will make a bid to re-write history by going back into the battlefield. For if he manages to rescue the POWs it would implicate that they could have won the war, that in reality they lost. One could say the action hero has been a reflection of its audience’s social values, alternatively they could be considered as products of propaganda.

Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jackie Chan are not Americans by birth, unlike Stallone. Thus the former two had to go through an Americanisation through films such as Red Heat (Walter Hill, 1988, US) and Rush Hour (Bret Ratner, 1998, US). Co-stars such as James Belushi and Chris Tucker, would spend much of the narrative assimilating their counterparts to American culture; often by offering ethnocentric remarks. Ending with the eventual acceptance of eachother’s differences.

But while Schwarzenegger would essentially be accepted as American, we would see Chan’s nationality remain an issue within his films. The fact he was Chinese would play into the humour of his Hollywood releases, it became part of the narrative as he portrayed a fish out of water in films like Rush Hour and Shanghai Noon (Tom Dey, 2000, US). Interestingly these films are not as popular in his native land. Suggesting his native audiences has not enjoyed Hollywood poking fun and making light of his national identity. It seems to have become an asset for Chan’s star persona, particularly in Hollywood. Because it helps to disarm the audience who may feel alienated in watching a foreign action star; who may not reflect them in the same vein as Rocky or Rambo.

The (Vulnerable) Action (Family) Man

With the 1990s and the decades that followed, we saw the emergence of an action hero with a lower level of bloodlust; he was no longer a lost loner like Rambo. Instead he was the family man in True Lies (James Cameron, 1994, US). He was still fighting the enemies of his country, but now anxieties were domestic rather then political. The action had always been coupled with an emotional counterweight as part of the narrative. Now the action story was counter balanced within the context of family. Not only did the action hero mellow as a result, but he was made more vulnerable as his enemies targeted his family unit. Yet regardless as to whether he saved them or not, vengeance was still sure to be his.

With the 1990s and the decades that followed, we saw the emergence of an action hero with a lower level of bloodlust; he was no longer a lost loner like Rambo. Instead he was the family man in True Lies (James Cameron, 1994, US). He was still fighting the enemies of his country, but now anxieties were domestic rather then political. The action had always been coupled with an emotional counterweight as part of the narrative. Now the action story was counter balanced within the context of family. Not only did the action hero mellow as a result, but he was made more vulnerable as his enemies targeted his family unit. Yet regardless as to whether he saved them or not, vengeance was still sure to be his.

Old western films such as Red River (Howard Hawks, 1948, US) featured narratives where an ageing cowboy would pass the torch to the younger generation. In this film an ageing John Wayne must concede that his time is over, acknowledging that its time for the next generation (in the guise of his foster son) to take charge. Within the context of the old westerns this was a metaphor, for how the days of the Wild West were coming to an end, to make way for the laws of civilisation. There had been nostalgia for a way of life that had been lost, yet a celebration of something that’s inevitable. Similar father & son narratives have popped up in recent times in the form of Indiana Jones 4 (Steven Spielberg, 2009, US) and A Good Day To Die Hard (John Moore, 2013, US). Harrison Ford and Bruce Willis essentially play old men who are not quite what they use to be; grudgingly they have to learn to pass on the torch, much in the same vein as John Wayne does. But the nostalgia within these films is not for any ideal way of life, but it is self referential in that they bring attention to their heydays as action stars. There is an unspoken acknowledgement that they have aged, that they are part of an era of stars that is slowly but surely fading away.

One common theme that has run throughout the films mentioned above is over the father’s absence from the family and how they spend the course of the film to compensate. While they prove apt for any action situation, the hero seems to fall short when dealing with emotional conflict. If Rambo needed gun powder to disinfect a wound, a hug would suffice for the modern action hero. Today the likes of Jason Bourne need to settle down with someone they love, rather than to destroy an agency in a quest to find his identity. But when his love is taken away from him, he reverts back into the action hero of old and extracts his vengeance. These days the action hero needs to be provoked into a level of bloodlust, a lust which came naturally to the likes of Rambo. Yet a vulnerable side of the action hero can be traced as far back as the Rocky series, for Adrian was the softer half of Rocky.

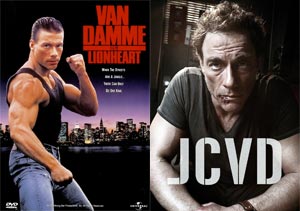

Today it has become acceptable for our hard bodied heroes to weep. You don’t need to look further then the promotional images of two Jean Claude Van Damme films. If we start with the image of Lionheart (Sheldon Lettich, 1990, US) he strikes a pose of someone poised for action. He exudes an aura of power and strength, anger and hostility. He holds a look that demands respect. But if we move towards JCVD, we see someone who is hurt; physically and emotionally, as illustrated by his cut lip and his sad frown. He is an image of weakness, with a pathetic expression that asks for sympathy. Add to that the powerful monologue he delivers within the film itself, commanding a moment of pathos which within its context is unusual, as Van Damme becomes the hero we don’t want to be, for he becomes true to life.

Today it has become acceptable for our hard bodied heroes to weep. You don’t need to look further then the promotional images of two Jean Claude Van Damme films. If we start with the image of Lionheart (Sheldon Lettich, 1990, US) he strikes a pose of someone poised for action. He exudes an aura of power and strength, anger and hostility. He holds a look that demands respect. But if we move towards JCVD, we see someone who is hurt; physically and emotionally, as illustrated by his cut lip and his sad frown. He is an image of weakness, with a pathetic expression that asks for sympathy. Add to that the powerful monologue he delivers within the film itself, commanding a moment of pathos which within its context is unusual, as Van Damme becomes the hero we don’t want to be, for he becomes true to life.

The Shape Today

I conclude that Daniel Craig’s run of James Bond Movies seem to be an amalgamation of the various qualities and values I have mentioned above. If not then as a character he at least engages with what it has meant to be an action hero, by adopting some aspects while deconstructing others. He has a mastery over his urban environment, he posses the hard body and tenacious spirit. Yet he has no family and he loses his love interest. The last two aspects are frailties that have plagued the action hero of modern times. Yet interestingly they are deconstructed within the films Casino Royale (Martin Campbell, 2006, US) and Skyfall (Sam Mendes, 2012, US). Bond starts out with a form of these vulnerabilities but seems to shake them off as the series progresses. This in effect devolves him into an old school action hero that pre-dates the family man of the 1990s.

It should be noted that despite the British nationality of the character and the setting of the film; this is a product of Hollywood. Daniel Craig’s Englishness is overstated within these films. It’s not quite in the same vein as Jackie Chan, which you could argue has been derogatory in Hollywood. Instead its part of the charm of the character, as it celebrates him as the British bulldog of determination. At the same time they make him acceptable to an American audience by reflecting a political anxiety that is shared by both Britain and America. A scene in Skyfall which illustrates this is where M addresses an inquiry, as she makes her speech; Bond relentlessly pursues the villain on foot. She states: “I’m frightened because our enemies are no longer known to us, they do not exist on a map, they are not on a map they are individuals” she goes onto assert that “the world is no longer transparent now its more opaque” and asks if they feel safe from the threats that now reside in the shadows. This threat is a clear allusion to terrorism. What the film tries to justify is its escalation of violence, by asserting that it’s in reaction to a threat that has escalated in its size. Indirectly justifying the methods that are now employed to fight the war on terror today. Methods many have criticised in the real world as unjustified.

It should be noted that despite the British nationality of the character and the setting of the film; this is a product of Hollywood. Daniel Craig’s Englishness is overstated within these films. It’s not quite in the same vein as Jackie Chan, which you could argue has been derogatory in Hollywood. Instead its part of the charm of the character, as it celebrates him as the British bulldog of determination. At the same time they make him acceptable to an American audience by reflecting a political anxiety that is shared by both Britain and America. A scene in Skyfall which illustrates this is where M addresses an inquiry, as she makes her speech; Bond relentlessly pursues the villain on foot. She states: “I’m frightened because our enemies are no longer known to us, they do not exist on a map, they are not on a map they are individuals” she goes onto assert that “the world is no longer transparent now its more opaque” and asks if they feel safe from the threats that now reside in the shadows. This threat is a clear allusion to terrorism. What the film tries to justify is its escalation of violence, by asserting that it’s in reaction to a threat that has escalated in its size. Indirectly justifying the methods that are now employed to fight the war on terror today. Methods many have criticised in the real world as unjustified.

Craig’s stunt work had been used as part of the promotion of the film. Here they were trying to sell us the tension of reality as we saw Bond contend with a villain; atop a crane that towered above everything else in sight. In the same vein of Jackie Chan, they were trying to work within a realm of possibility. Yet not to the same extent as the Hong Kong star, for CGI and trickery were necessary for the more elaborate sequences. During the parkour (free running) chase in Casino Royale: we see bond contending with the urban environment in the pursuit of a bomb maker; who happens to be the superior free runner. Yet Bond is the action hero, any short coming is compensated with his tenaciousness. Where as the villain gracefully leaps and bounds around tricky objects; Bond relies on his brute strength to literally crash through walls. The human spirit transcends the weak body. Something Bond will have to do in Skyfall once it becomes apparent he is no longer fit for duty: physically or psychologically. Here they deconstructed the hard body of the hero, in the literal sense that he has been damaged to the point of losing his strength & co-ordination. In doing so they reveal a strength of his character in his refusal to resign to his fate, his only option should be retirement. Instead he opts not to be dictated by his circumstance, he makes his own luck. As they assess him for his psychological fitness, they ask him what first comes to mind when he hears the word Skyfall. He refuses to answer and storms away, the implication is that he is troubled.

For Skyfall actually turns out to be the name of Bond’s childhood home. It is also the setting for the climax, which results in the destruction of the building. In addition to the demise of M. A maternal figure who dies in the arms of Bond. The family vulnerability is essentially eliminated in not only the physical sense, but in a metaphorical one too. As illustrated by the fact that Bond returns to duty, fitter then he was at the start of the film. If we look at Casino Royale and his love interest Vesper. We see a Bond more interested in retiring with his leading lady, as opposed to a life of action. She proves to betray his trust, which leads to the circumstances of her death. M asks Bond if he has “learned” his lesson: trust no one. Bond hardens himself and responds that he has, he becomes a colder person. But upon learning that the betrayal was in order to save his life; he moves to action. He doesn’t allow himself to feel self pity, he looks for no sympathy. Instead he pursues revenge, taking a sadistic pleasure in the process. These films essentially strip away the frailties of the modern action hero, thus forming a shape similar to the action heroes that preceded him.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Really loved the way you incorporated the Bond reboots into the article, your comparison of Casino Royale and Skyfall and how the character devolves throughout was very well done indeed.

Great article man!

Thank you very much, you have no idea how rewarded I feel as I read & reply to your comment.

One thing that occurs to me now (rather annoyingly) is that I could perhaps of mentioned a moment in Skyfall where Mallory implies that Bond is an old man. His complete disdain to this is reflected in his determination to complete the mission, in doing so he kinda de constructs the whole passing of the torch notion, especially as he has no one to pass it to, just yet? Personally I’d hate to see the series go down that route, because the torch is usually passed onto a fellow far to lame to be worthy of it.

Now that I think about it, I could of probably brought Batman to the discussion but I’d probably would of had stretched myself far too thin.

Thank you very much for reading.

Oh maan I miss those old hulks! It’s almost sad to see Arnold and Sylvester doing action these days. The 80’s mindless action! We all crave for it!

I think Sly has a lot left in him, Arnie I’m not convinced any more… His acting can’t compensate for his lack of the hard body, he looks relatively frail for the role now. I don’t think its fair to judge the stars in relation to their heydays, but you can compare them in relation to their competition. With that said: The Last Stand was a masterpiece compared to Bullet in the head… that film made me cringe, never found a character so whiny & annoying before I saw that rubbish. The Axe fight at the end was the best part of that film, worth youtubing at least.

Eventually we will have to wave farewell to these guys, the frustrating thing is that the generation of action stars that have followed: don’t have the same charm or charisma.

I have a friend who would agree with you on all counts except that he likes Matt Damon a lot.

Very interesting article.

Very insightful retrospective of the changing of the action hero. I remember the days when producers were looking for the biggest muscles to star in their action movies… now it is that AND their ability to perform. Improvement I say.

I agree with Dale above.

The return of Bond to something closer to the classic Bond by the end of the film, while still ‘destroying’ his past as well as the themes of the previous 2 films was a masterstroke and probably kept the franchise alive.

Craig’s run of Bond has saved the franchise after Brosnan’s take that got worse and worse by each release.

Great comment. Craig is as good as Brosnan was bad.

Great stuff on Bond. I think the deconstruction of Bond is some very interesting stuff. Reading back at a lot of reviews of Skyfall, there were many people (myself included) who thought it was a film that was bringing Bond back to relevance in a time when “heroes” aren’t needed all that much. After reading this, maybe Skyfall does more than just bring 007 back to relevance, but rather the entire concept of the “classic” action hero.

I do want to mention the shift in the action film towards the comic book industry as well, because I do feel that comics have played a huge role in the evolution of the action film genre. There’s a whole lot of room for expansion on this topic.

I’d have to give the comic book thing some thinking. I think it certainly has changed the focus on not so much as to what the human body can do but rather indulges in the fantasy of what it can’t. I use to be a keen reader of Marvel comic books, but I was never a huge fan of the films even do I enjoyed some of them.

I think the trouble with “heroes” today is that the stories tend to polarise the good against the bad. When the politics of our world isn’t so black and white, its rather one shade of grey vs. another.

Probably why a show like game of thrones is so popular, there is no side that’s completely bad, even the Lannisters have a Tyrion amongst them!

Very cool. Also, Jackie Chan > steroids.