Shock Art: The Name Says It All

Step right up, folks! “Shock art”—the name says it all: Works that are bound to leave you amazed. Granted, sometimes when we look at a challenging piece of art we cannot see past our fist shocked impression, so we end up disregarding any meaning or vision. But isn’t the purpose of art to cause emotion, to make you think, to bring attention to an issue and to spread fervor? Sensationalized as shock art, pieces such as Portland-based artist Sarah Levy’s menstrual-blood portrait of Donald Trump in protest of the presidential candidates’ sexist and outrageous comments; Guillermo Vargas Jiménez, also known as Habacuc’s, exhibit of an emaciated dog in a gallery in Nicaragua in 2007; “Piss Christ,” a piece of art by U.S. artist Andres Serrano, and Niki Grangruth and James Kinser’s nude exhibit of “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” [“After Picasso”] 2012 are stigmatized, but these pieces will never not be art simply because they shock. The visual appeal of these pieces is less important than the massage behind them.

Art—political and revolutionary, an extension of the self, a movement, a networking facilitator and agent, a language, a communication powerful enough to save lives, the mother of unity and rebellion, emotions portrayed visually, unique and cannot truly be replicated. People sometimes take a morbid and grotesque approach within the realm of art. The pieces shock artists display often start arguments that challenged ethics, and the definition of “true art.” Disputes have sparked regarding the validity that menstrual blood murals, a starving animal exhibit and a figure of Jesus Christ submerged in human urine, can stand as presentations of true art. Instinctively, many people experience discomforts and strong rejections towards not only the art, but also the artists, hence challenging and questioning their authority and qualification as an artist.

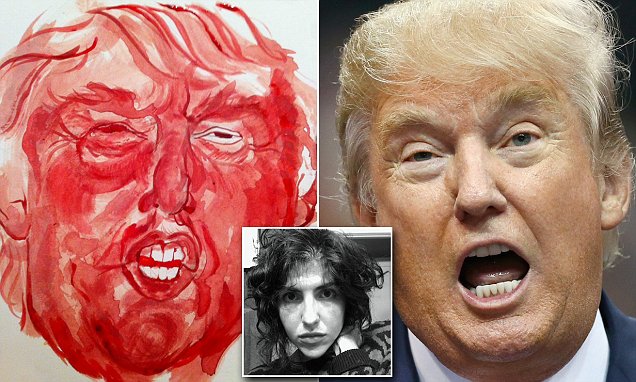

On a recent September day, Portland-based artist Sarah Levy used her menstrual blood and a tampon to paint a portrait of 69-year-old Donald Trump after implying Megyn Kelly, was on her period during the Republican debate. As unappealing as a menstrual blood painting is, Levy begs the question: Why not use the most natural by-product of the female body—which Trump views as problematic—to communicate her emotion and view of the candidate? Levy embraces the disdain image of feminine release and uses it to communicate her feelings. Levy tells USA Today, “I heard the comments he made to Megyn Kelly and I was outraged that he was basically using women’s periods not just to avoid a political question, but also to insult her and all women’s intelligence.” Trump expressing outrage, is literally depicted through the blood he joked about, which, in turn, has brought outrage to the American people. Kaboom! Levy ingeniously brings attention to a national issue, and the devotion to her craft is absolute.

Zero impact could be celebrated if Levy conventionally used red paint. But would she still bring attention to the issue? Of course not, risk is a part of artistry. Who cares about an artist who never takes risks? Better yet, who can grow from a riskless creator? Art must drive and stir up emotions in people. The vision behind a creation must be to make someone feel something; otherwise, the work is meaningless and invisible. Art in general, is becoming more and more dispersed. The rising significance of community-based cultures, the increased targeting of niche markets, the dissolution of the boundaries between high and low cultures and the associated ethic and geographic diversity of audiences have lessened and even delegitimized the need for centralized fascist voices dominating art.

Gradually, decade-by-decade, changes in the way we think and believe have helped growth a working social system. Thanks to evolution, we collaborate on ideas and share thoughts that navigate innovative practices. Art must evolve or atrophy and die. Consumers glean ideas from past creators, illustrators and builders. These innovators speak to us, and influence us to manifest a name for ourselves. Around the world, artists are provided cathartic oases as an escape from the mundane complications of everyday life. Whether we are performing the art, listening or watching, we are constantly incorporating different forms of art into our everyday lives.

By diminishing the role of the artist in the evaluation process—in effect, making the end-user the consumer, the most effective and persuasive arbiter of quality—market-driven culture leaves little room for minority points of view, edginess, difficulty or controversy, whether in the cultural mainstream or sometimes even at its increasingly embattled margins. It is the artist. Conventionally, who often supports or analyzes culture against the grain of popular tastes, indifference or hostility. In the best of circumstances, the artist serves as a kind of aesthetic mentor, introducing an audience to challenging, little known, or obscure works offering insight that might make a work more accessible, engaging, profound or relevant.

In Nicaragua during 2007, a circulation of emails, blogs, petitions and websites claimed a dog—already starved from living on the streets—was chained then denied food and water during an exhibition at Condice Galeria put on by an artist named Guillermo Vargas Jiménez, also known as Habacuc. A news release from the gallery, however, told a different story. Juanita Bermúdez, the director of Condice Galeria, says the dog was at the exhibit for three days beginning Aug. 15. She says the dog was allowed to run free in an inner patio, except for three hours per day when the dog was on exhibit. Bermúdez also says the dog was given water and food brought by the artist himself. She says the dog escaped through the main gate of the facility during the early morning hours of Aug. 17, while a night watchman was cleaning the sidewalk outside.

Rumors banish the artist from their field of vision. The artist is often expendable in the process of determining what is good art, and what is bad art. Consumers have frequently played a vital, even public, role in influencing the shape, texture and direction of art, their value and relevance is growing increasingly tenuous in many sectors of mainstream cultural life. Vargas Jiménez’s vision for his shocking piece could be to grow activism against animal cruelty. Witnessing the dog as art brings discomfort and anger because it is a suffering life. Our morals and instincts may tell us Vargas Jiménez’s work isn’t O.K., so we mentally put restrictions on accepting the piece as art. The starving dog put on display, most likely, isn’t the first time anyone has ever seen one. But the animal is not on the streets, or in an environment of which the public is used to seeing it in, so a grave emotional response develops towards the animal. Seeing that single dog suffering alone also burns the image into memory, so after departing, the art piece is remembered. Now the next time we see a starving animal, we may think twice before walking away—too distracted with our own problems and busy agendas.

Vargas Jiménez says he got the dog—which he named Natividad—from the streets of Nicaragua. He says the display at the Codice Galeria, was intended to give tribute to a man named Natividad Canada, a 24-year-old Nicaraguan who died in a Costa Rican factory after being attacked by two Rottweiler dogs in 2005. The exhibit also reportedly included the words “You Are What You Read” written with dog food, a recording of the Sandinista National Anthem playing backwards and a censer in which burned “175 rocks of crack cocaine and an ounce of marijuana.”

In 1987 American photographer and artist, Andres Serrano, displayed “Piss Christ,” which may seem like a piece of shock art that doesn’t necessarily have much to say. Through the presentation of an anger driving work—a small plastic crucifix said to be submerged in Serrano’s own urine—the piece is dubbed a blasphemous sight spoiling for a fight. For almost three decades this photograph has attracted controversy. Let’s talk about this controversy for a second, some Christians believe “Piss Christ” is not only an attack on religion, but the work is set out to be unmissably heinous and adopts that offence as part of its meaning. Anger grew to a climax on Palm Sunday 2011 when French Catholic fundamentalists attacked and destroyed the photograph with hammers. Seeing “Piss Christ” creates anger, but why? What is in the art? Is the piece really an attack on religion? What does Christ mean to you? These questions can be answered if you meditate and look for meaning.

According to Serrano, anger was not his message. “At the time I made ‘Piss Christ,’ I wasn’t trying to get anything across,” Serrano told The Guardian. “In hindsight, I’d say ‘Piss Christ’ is a reflection of my work, not only as an artist, but as a Christian. The thing about the crucifix itself is that we treat it almost like a fashion accessory. When you see it, you’re not horrified by it at all, but what it represents is the crucifixion of a man,” Serrano says. “So if ‘Piss Christ’ upsets you, maybe it’s a good thing to think about what happened on the cross.” Alas, we see there is something in this powerful work for everyone. Serrano just asks you to do a little thinking and investigation. Examining and considering a work with an optimistic outlook is important. After all, art is all about freedom of expression, and we each have different ways of expressing; and we each can be misunderstood. As long as there is an idea or vision or meaning behind the work(s) produced, the public must accept expressions of art in their morbid forms. In a way, we are stuck with dealing with morbid art having value. We cannot judge someone’s creation as “not art” because it is shocking and makes us uncomfortable.

For personal connection and free thought to be established and generated about a work or idea, the analysis of “the artist” must take place. Weather it is in singing, designing, acting, cooking, writing, painting, debating, idealizing, comedy, etc., all who create are artists in their own way. But does this mean they possess canonicity (worth of studious attention)?

What makes an artist memorable and eminent? Within society we pass judgment on creators and their works, ranking each on a scale of “genius” by habitually looking at how well liked and accepted their works and ideas are by others. In this way we have made it possible for the word “artist” to be evaluated as either a noun or a verb. The noun form of “artist” being someone seen as a significant, talented influence and honorary example, as opposed to the verb, for example, a painter who paints, (receiving respect after the process of putting paint on paper.)

In part, becoming an “artist” revolves around what is socially accepted, valued and popular at the time of a work’s release into society. On the other hand, artistry is dependent on timing. Steve Jobs, for example, is an established “artist” through his creation of the multinational technology phenomena, Apple Inc. Since his ideas were relevant and valuable for this technologically advancing decade, Jobs gained worldwide respect in his creation. But creators like Socrates weren’t recognized for their work until after death. The audience of 423 BC Athens wasn’t ready for all the theories Socrates presented. But as centuries passed, we now give him his due honor and reverence.

Shock art brings to question the dependability of an artist. What were the artist’s intentions? Should there be a defined meaning? Firstly, there is no way to guarantee a specific message to be understood by an audience. Does this mean a message shouldn’t exist or an artist should not fight for his or her intended message? What if their message was taken in offence? Then is it relevant and necessary for the artist to speak-up? At the nitty-gritty, notoriety is the foil of many creators. The ability for others to form personal connection through the work of an artist manifests a good creation. An artist shouldn’t focus on controlling meaning. They release their work to the public, so they welcome the possibility of various opinions to be formed. Their vision should be expressed to facilitate a guided understanding and ownership for their work. Consumers who possess guided control can see legitimacy and meaning in the work, idea and vision, and possibly have a way to relate to, or simply generate interest in, that work. Giving this “power-to-the-people” is how an artist goes form “verb” to “noun.”

Still, an artist will find it difficult to be poise when someone misinterprets the vision he or she has for his or her created work. In order for the public to appreciate a creative process, character or mind-set, fighting for his or her preconceived vision is a golden quality of an artist—as seen by Serrano with “Piss Christ.” Well, what do you know! Speaking up is another way to upgrade the “verb” artist to the “noun” artist.

Now, here’s some debate: Some people say art has taken on too much of an ambiguous understanding. Maybe these works of “shock” are overstepping the boundaries of art. As defined, art is a human attempt to create something well. Therefore, it seems the word “art” truly does have an ambiguous meaning. Art can be almost anything. Cultures, religions and societies put restrictions on art to shape an identity for what art is. For example, Catholic works have an ethereal and puritanical look to them. Pop art works of Andy Warhol wouldn’t be accepted into the realm of Catholic works because of the restrictions on style—even if Warhol did a piece that uplifted the Catholic religion. This does not mean, however, that Warhol’s works are not art—just because they are not universally accepted. In relation to the works done in “shock art,” we have created a realm of restriction just as religions and cultures have done. But let’s just keep in mind; there is no all-knowing art god defining what styles are worthy to enter the monolithic art kingdom and what styles are not.

Standing in the way of consumers pondering meaning is a bona fide works of art versus a replication of art—some pieces of shock art challenge the viewer to think of the meaning, but the artistic authenticity is questionable.

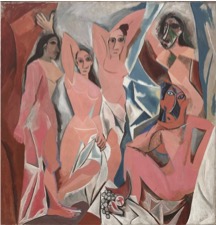

Appearing as a naked Liz Taylor (Denis O’Hare) from “American Horror Story, Hotel,” James Kinser models in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon [After Picasso] 2012. He is attempting a seductive female. His slim pale physique strikes five poses in the piece, wearing only makeup and a tiny black hat. A display of shock art, not intended for young eyes or gentle hearts. Male genitals aren’t visible but escaping pubic hairs leak the idea of a “V” where a “P” would be. Want more? Photographer Niki Grangruth shows a clear display of Kinser’s backside and the crack of his behind. Sexy. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon [After Picasso] 2012 aims to challenging traditional artists by promoting gender flexibility and empowering gender nonconformists. But this shocking piece fails to do so because of the lack in original visual aesthetics and the brash and alarming naked appropriations of women, originally sourced in Pablo Picasso’s work.

“Our intention is to retain the visual aesthetics of the original works, while reinventing the context of each piece through the use of a male subject, bodily positioning, the gaze and costume,” says Grangruth on her website. “Each work within the series [‘Muse’] intends to disrupt the socially-constructed male/ female binary.” Seems like a coherent vision, but why use the works of well-known artists as the foundation of the “Muse” gallery? Doing so is a bit too daring with a side of disrespect. Grangruth and Kinser’s “re-imagining” of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon [After Picasso] 2012 is an attempt to give aesthetic equality to a work that is studied in books throughout academia. Picasso was wrestling with the problem of depicting three-dimensional space in a two-dimensional picture plane. In Les Demoiselles d’Avignon he used primitive masks, his cubist technique and sexual subject matter. Picasso’s influences on surrealism and cubism rejected popular aspects of traditional artists of his day and did so through his original visual aesthetics.

![Les Demoiselles d'Avignon [After Picasso] 2012, by Niki Grangruth and James Kinser.](https://the-artifice.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Untitled.jpg2_.jpg)

Grangruth and Kinser challenge viewers to accept their knock-off version of Picasso’s historic pieces, and that’s cheating, not to sound cavalier, but come on. The message of pro-gender flexible art in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon [After Picasso] 2012 is too abnormal to not have a strong impact through a completely original organic composition or visual aesthetic. Annoyingly, Kinser and Grangruth rely on the master paintings of well-known artists like Picasso to spark and conjure openness and receptiveness to “Muse.”

Kinser’s appropriation of women in the work is disappointing. Being a male, Kinser must show delicacy and beauty so audiences know he is trying to look like a prostitute based on Picasso’s work. It’s disrespectful to women and not a coherent way to activate empowerment for gender flexibility. Grangruth says they are trying to reimage the context, but she and Kinser actually changing the context to fit their own agenda—promoting gender flexibility through art—but essentially, failing to drive the message home.

It is understood that we all strive to demonstrate value in the things we do, which has become harder over the years, not only within art, but also in justifying authority as individuals in relation to dependability, purity and originality. The values we lack in our personality make it harder to accept what is produced by one another, especially when it is boldly “original.” Shock art has disturbed individuals, some to the point of being angry. But like a child, asking a parent thousands of questions to understand the world—consumers, be kids, and question the intentions of an artist. Emotions cannot validate ignorance. An effort must be made to understand what we see, so we can respect one another. Let’s exercise tolerance. Remember, the creator and his or her audience is connected in this living system of growth and exchange. The aesthetic pleasure of an art piece is the shallow shell. Let’s dig deep and uncover the meaning of a visual work, and bask in the value.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I wish artists aspired to be good rather than ‘shocking’.

All great art is shocking, it takes you out of yourself, which is a shock – , but not all that is shocking is Art.

I remember the Chapman Brothers, who set out to shock gratuitously with early works, and then with Hell II created an intricate and sublime work of art on a par with some of the best medieval church altar and door carvings. Damien Hirst’s early works were shocking (especially if you didn’t like seeing maggots crawling across the floor of the old Saatchi Gallery in St Johns Wood) but his later works are a total bore and artless which just make his early hits seem like flukes. Nan Goldin can shock on first viewing, all dead drug addicts and shit-faced hookers, but then you realise she is just photographing her friends and they go from shocking to intimate.

So the shock of the new soon disappears when the novelty wears off and then the true worth of a work of art and artist is revealed.

It is being produced to entertain .

No more, no less .

The only thing thing about modern art can shock is the bleeding price!

I’m glad “Piss Christ” is being represented as a think-piece, despite being shock art as well. The photograph says a lot about how a modern Christian can feel frustration with the commercialization of a serious event in the religion. His piece still rarely gets the respect it deserves, so I’m glad this article discusses it in a positive light.

I definitely agree that it’s important to move past the initial shock (and bodily fluids…) and analyze the backgrounds of these pieces. Excellent article, and very intriguing examples.

The shock in art starts out as a typical shock from the viewer and then they learn that the “shock” is actually the meaning behind the work. Also, a shock does not have to come from only artwork, it can come from things such as music and poetry. I never thought of it that way until I read this article.

I appreciate the concept of Grangruth and Kinser and their interpretation of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Additionally, you have introduced me to some pieces and artists unfamiliar to me. Thank you.

Since the demise of the historical avant-garde (DADA, surrealism), art no longer has the capacity to shock.

Art is there to shock, it is never shocking, if you wish to be shocked, go elsewhere.

Shocking ‘art’ almost uniformly lacks thought, and creativity, let alone originality. More often adolescent imaginings and undergraduate humour. The skill level of practitioners is negligible to the point that anyone can call themselves an artist if there is a muggins to ‘discover’ them and buy their stuff, with a big enough PR machine to elevate them to the next big thing.

I’d actually like to see a period of no shock. Ease off the hysteria and have some serious discussions for a while without shrills diverting the debate.

I suppose the purpose of art is to challenge current perceptions and that remains a necessity in anything but a perfect society. I’d guess we’ll be needing challenging art for a long time yet.

No, no and no.

Look at some of the 15-16th C Dutch and Flemish painting – it could, almost, be described as being formulaic – rural, pastoral and domestic scenes, townscapes and landscapes – nothing is being challenged.

Their beauty and art lie in those tired old talents of excellence of composition, brilliance of technique and manipulation of light.

Certainly, art can be challenging but that is not its purpose.

No – art has no purpose other than creativity for its own sake. Why does art have to be burdened by some purpose?

In my opinion the art that seeks to offend and shock are usually trite in essence.

I do not believe that those artists that are deemed shocking, intended to be shocking, they just wanted to bring the nature of traditions into question.

If it’s shocking and offensive to question the status quo, then I’m sure many will be considered thusly in the future.

The age of innocence has gone forever. Nothing shocks. Sex, Headless people…With youtube and twitter, it is “Been there. Done that.”. In case someone is shocked, they must be pretending.

You give up too easily! When commercial conformity is overpowering, shock is inevitable.

I can think of plenty of things that would shock. I’d probably get moderated out if I described them in detail. But eg, things involving children. There are plenty of things our society still can’t accept – and for good reason.

I agree. With the popularity of social media, you are certain to stumble upon something you wish you hadn’t seen.

You’re always going to shock/bother/annoy someone…

But, we’ve had to suffer the likes of people tatooing live pigs, or innumerable “pushing the boundary” movie sex scenes – all of which just make you want to throttle the “artists”.

At the end of the day, if you choose to shock and yet curiously convey nothing, then you should be banned, to the bottom of the sea with you!

This analysis provides a wonderfully informative look at contextual theory behind “Shock Art.” Each piece discussed within this article and in the realm of “Shock Art” is worth analyzation, not just for shock value but the way each depiction arouses personal perception of art’s value. Is all art “good” simply because it expresses an idea or emotion? Can a piece of artwork only be considered effective in its impact if it is created with either somber or raw intent? Upon first view, some of these examples such as the menstrual Trump and “Piss Christ” appear typical paintings. The descriptions reveal unconventional approaches taken by the artists, some of which I first found slightly repulsing. The artists’ efforts in the pieces examined translate as experimental endeavors. Shock does not seem to be as significant as the artistic methods applied. Though art has no limitations, what is categorized as “Shock Art” now will evolve into something more shocking and unorthodox in the next twenty years.

A very fascinating read. I definably feel that shocking art is only as good as how strong the meaning behind it. For example, the painting of Donald Trump made from period blood may seem strange out of context, but with knowledge of, as you said, Donald Trump accusing Megyn Kelly being on period as a way to avoid the questions and to make Megyn Kelly look emotional, the point of the painting totally makes sense. Thank you for exposing me to some interesting examples of shock art.

A distinction should always be drawn between shocking ‘art’ and shocking imagery in art.

As soon as art shocks, it ceases to be art and becomes Vaudeville. We have always known this. The point of art is an enquiry into beauty. Any idiot could have told you back in the 1960s that in trying to make art about shocking people it would necessarily become a race to the bottom, the rocky end of which will be serious art critics sagely nodding in front of a can of crap.

I don’t know who decided it was the role of art to shock, but it has exposed us to the puerile sweepings of some very immature minds since the pissoire raised its finger to the world.

Art, in this context, is about challenging conventional wisdom, about pushing boundaries that challenge perceptions. If the viewer/reader/listener is ‘shocked’, it says more about him/her than the ‘work of art’ in question.

I’m shocked every day even though I have very few taboos. But in a world of instant media my shock is usually resolved or forgotten within 24 hours.

I suppose I do understand the appeal to make shocking art. Aesthetically, the more reaction, the more discourse occurs around the piece–hypothetically making the its rang as subject more expansive. Although, there is something to be said for nuance. Great article!

Not to sound pretentious, but as an artist myself, I often find that art critics find meanings in the artwork that the artist did not intend for. Most artists bullshit — this is the truth. As one myself, I would often draw random doodles on my notebook, and some of my friends would debate among themselves the meaning of my scribbles. Sometimes I go along with it, but eventually I reveal that my drawing are meaningless.

My drawings usually consist of nudes. This was natural to me, so I never considered that my drawings were shock art. Of course, my sketches of naked, suffering human beings often shocked people. I would often make up a meaning — “Oh, this drawing represents the suffering of women in the world,” to describe a leashed woman on all fours. “Oh, this drawing represents the desire to modify one’s own image through plastic surgery,” to describe a grotesque collection of deformed figures. Some it is definitely true that artists bullshit, very often actually. So, I would advise people not to always believe the meaning that the artist puts forth. For example, Andres Serrano, the creator of ‘Piss Christ,’ said that his photograph represented the commercialization of religion, of Christ’s image. The art critic Camille Paglia called him out on it, saying “So that’s why you called it ‘Piss Christ,'” believing that the artwork was intended to irritate people instead of enlighten them.

As an artist, albeit a horrible one, myself, I believe that the value of an artwork lies in the amount of skill and creativity needed to produce it, as explained in Dennis Dutton’s TED Talk “A Darwinian Theory of Beauty.” He explains that the value we place upon a work of art is determined by the amount of skill and work it took to create it. The more difficult, the more valuable. One can clearly see this in the Apple app Auxy Music Creation, which allows the user to create music simply by tapping the screen. The resulting beat often sounds amazing, but the user does not feel like an accomplished musician simply because he/she tapped the screen a few times.

Another topic that the writer brought up was the question of the canon, the ‘official’ list of great and important works of art. The controversial art critic, Camille Paglia, believed that the canon is determined by artists themselves, not the consumers, whether it be art critics or the public. She said that the worth of an artwork as part of canon is based on the influence that it had on other artists over time.

The problem that I have with this article is that it proposes two mutually exclusive theses, which has the effect of undermining both points, and thus rendering the points in the article untethered to anything tangible. This gives the appearance of trying to have a cake and eat it too. Personally, I do thing that there is an objective good, and bad in art, in terms of quality (detail in work is a factor that I would put forth).

I believe that artist’s intentions are very important when considering an artwork, because art is not simply visual, and I don’t think it ever truly has been only visual. Art is meant to evoke emotions, and sometimes, maybe, it is supposed to cause shock and disgust because it furthers the message. For example, the Donald Trump portrait was intended to display her disgust with Trump’s political position. In my mind, she has perfectly encapsulated her message by using this medium.

This was a very interesting read and well thought out article. Thank you for considering this issue.

Wow. This article really tossed me down memory lane. I visited the Museum of Modern Art in Malaga, Spain and personally encountered shock art for the first time in Summer 2015. The exhibit had a video of a nude woman by the shore, face not shown, hula-hooping a barbed wire hoop. In slow motion, the video captures the metal cutting through her waist. In another, a woman cuts her hands and placing them abover her head and facing the wall, drags her hands down the wall spreading the blood. Another video showed a nude woman painting herself in glue and violently rolling in feathers, paper, and other mediums. The year ranges of these videos took place during the early 1950-70 or 80’s. (Forgive my failed memory). However, it was in a period when woman were increasingly objectified. They woman figured it would be best to destroy their own bodies than to have others do it for them.

The last sentence:

“Let’s dig deep and uncover the meaning of a visual work, and bask in the value.”

is a good way to summarize the problems this article has. In no way is shock art always visual. In no way does art always have value.

Thanks for drawing attention to the selection of pieces, though, that has value.

If the only legitimate purpose of art was to shock, ISIS would be the greatest performance troupe of all. Art has no ‘purpose’. It does serve many functions, from the aesthetic and exalting, to the confusing and bracing and challenging, as broad as human emotion and experience. The vast majority of great art has had little or nothing to do with ‘shock’, a relatively modern conceit.

I think Serrano’s PC resonates because it combines the paradox of a beguiling, mysterious image, with a discordant back story. The story makes the shock; the image makes the art.

Duchamp’s Fountain openly confronted the constraints of artistic merit of the day; it was not offensive to religious or moral standards. Much of Ai Weiwei’s politically energized art is not shocking, but is profoundly jarring and thought-provoking, the steamroller to Hirsch and Koon’s gnats.

Pruriently charged art does not elevate the work just because one can claim to be shocking social conventions.

Originality does not have to be shocking; too many artists fail to understand that making art shocking does not make it compelling, or good. The shock is not the message.

To the contrary, any sincere artist tackling charged issues actually must carefully self-censor, in order to balance the intended messages against the loaded baggage conveyed by blatantly exploiting the most immediate, flagrant approach, which will likely bring quick attention, but leave the works as obvious, trite, shallow, manipulative, cliched. Can the artist honestly say the strength of the art can carry the shock, or is the shock there to shore up the shortcomings of the art?

I totally appreciate shock art. I would never buy it and have it in my collection, but I am glad that it is being made. I have seen a few of the pieces mentioned here in real life, and I must admit; it was totally worth the effort. This kind of art inspires controversy and sparks debate. It gets the conversation going! And that is what I love about art. It provokes otherwise dormant minds to action and inspires a state of constant change. I friend once said to me “I’d rather see you offended and improving, than see you happy and be the same forever.”

Very interesting. This reminds me of Marcus Harvey’s “Myra” (1995), a painting of Myra Hindley (of Moors Murders fame) that I saw when I was an undergraduate. The portrait seems pretty normal … until you realize that it’s made up of infants’ handprints. Very creepy – but it definitely makes an impression. I think there can be a lot of power in confrontational art. Like any type of art, it doesn’t always work – but when it *does* work, it can truly make viewers think.

I think shock has its place (appropos that menstral blood from the artist’s “wherever” was used for Trump’s portrait). A shock for a shock. But it can often be used as a gimmick, masking for lack of talent. I enjoyed the article, and learned much.

Interesting essay. The artist who protested against Donald Trump in an unusual way is, admittedly, an odd thing.