Subtitling for Cinema: A Brief History

“Every film is a foreign film. Foreign to some audience somewhere around the world. It is through subtitles…that an audience can experience different languages and cultures. And behind every foreign film that brings a culture to a viewer is a subtitler”. Sandeep Garcha (Narrator). ‘The Invisible Subtitler’ 1

With the arrival of the 120th anniversary of the first appearance of text accompanying the projected moving image, this article will trace the evolution, and occasionally amusing history, of Audio-Visual Translation (AVT) for cinema. From hand-written or printed inserts between frames (commonly termed ‘intertitles’) to optical projection, hot-metal presses and chemical processing, to laser subtitling and digital encoding – this is a story about inventors and inventions, innovators, eccentrics and entrepreneurs and what the future may hold for AVT in general, but first there is an historical question to be addressed.

Which came first: Intertitles or Subtitles?

To this day there is still disagreement in Academia about when the terms ‘intertitles’ and ‘subtitles’ first appeared, although the origin of the former may be more recent than many would suppose. In the 2013 edition of Film History: An International Journal 2, Professor André Gaudreault states that the Roberts dictionary traces the French ‘intertitre’ back to 1955, whilst Oxford Dictionaries claim that the English ‘intertitle’ originates in the 1930s. As if to muddy the waters still further, the hyphenated term ‘sub-titles’ dates from 1826, in its literary context, although there is evidence to suggest that as ‘subtitles’ it was always the default term for what are generally called intertitles 3. So whilst it seems that the question asked above may never be answered to everyone’s satisfaction, this much is clear – ‘intertitles’ is a retronym (as is ‘silent movies’), but for the sake of simple continuity and to avoid further confusion, it will be used hereafter when referring to the inserted title cards of the ‘silent movie’ era.

The First Intertitles Appear

Auguste and Louis Lumière, Georges Méliès; Thomas Edison – these are just a few of the famous names that usually spring to mind when thinking about early film making, whilst those who created and developed intertitling still remain largely unknown outside of the world of the professional silent film cineaste. For example: the former stage magician and illusionist, Méliès’ first film viewer (a variation of the Edison Kinetoscope 4) was manufactured by the British innovator and visionary film maker, Robert W. Paul 5 who, in April 1896 and almost by accident, developed a reverse-cranking mechanism, which allowed for multiple exposures of the same film stock. Paul included this ingenious new device in his ‘Cinematograph Camera No.1’ and it soon proved its worth with regard to on-screen titling.

However, did Paul also invent intertitles? This question is still a matter of debate among scholars of early cinema, as the British born, American cartoonist and film maker, James Stuart Blackton 6 may have been experimenting with similar titling in 1897, a full year before Paul became the first officially recorded film maker to use intertitles 7. Unfortunately, there is scant physical evidence surviving from this era with which to prove the case either way. Nevertheless, in 1898 Paul exhibited Our New General Servant 8, an intertitled light drama, just a few minutes in length and with only four scenes, in which a woman discovers her husband kissing the housemaid then promptly dismisses the maid. Imagine that same scenario today – the wife would likely dismiss the husband instead and the maid would undoubtedly sue for sexual harassment. How times, and attitudes, have changed!

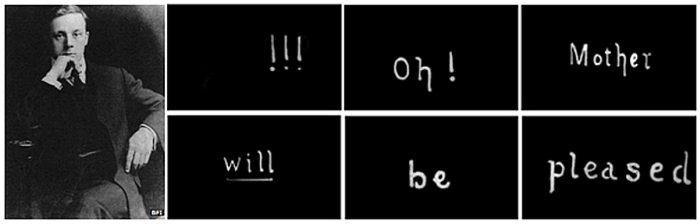

As the 20th Century dawned, experiments in titling continued. The year 1900 saw another British film maker, the wonderfully eccentric Cecil M. Hepworth 9 present his intriguingly entitled comedic short film, How it Feels to Be Run Over 10, in which the camera operator does indeed appear to be run over by one of those newfangled horseless carriages; a deft touch of in-camera trickery on the part of Hepworth, which Méliès would have undoubtedly appreciated. The film ends with a curious hand written title sequence that reads simply ‘!!! Oh! Mother will be pleased’, which hints at Hepworth’s rather bizarre sense of humour, as does the following quote from Hepworth: “There was nothing of courage in what I did. It was always just a lark for me…I was suckled on amyl acetate and reared on celluloid” 11

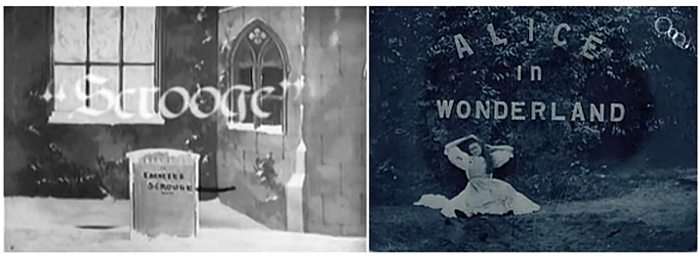

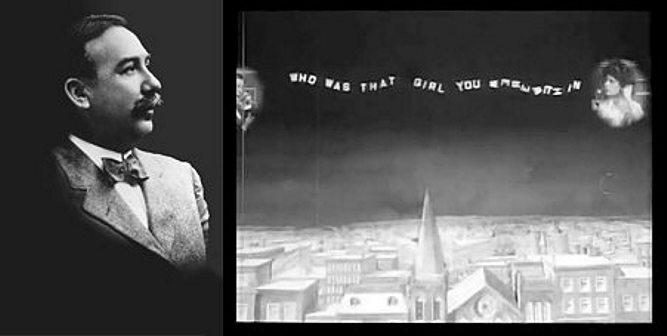

One year later and Paul’s reverse-cranking mechanism was put to effective use in his 1901 production of Scrooge, or, Marley’s Ghost, 12integrating the word ‘Scrooge’ into the opening shot and a similar technique was employed by Hepworth for his 1903 film Alice in Wonderland 13. The same year, in America, the Edison backed, Edwin S. Porter’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin 14 (frequently misidentified as the world’s first intertitled film) was released and in 1907, Porter’s College Chums 15 featured a truly imaginative use of what, in the modern world, could be termed ‘verbal texting’ during a telephone conversation in which a young woman berates her fiancé after seeing him with another woman.

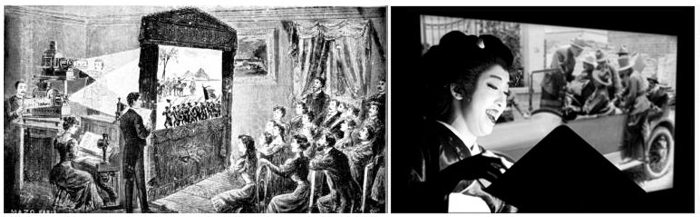

Without fanfare or pomp, intertitles gradually increased their presence and the following decade was a time of near constant innovation; one that lead to titling overall becoming ever more elaborate in its design and use of text. Expository and dialogue intertitles became the norm – the first explaining plot points, the second illustrating the actors’ lines. Opening title sequences began to list the names of the production companies and by 1911, also credit the director and stars of the film; and with musical accompaniment – piano, organ, string quartet, even a full orchestra at times, ‘going to the movies’ took a step closer to the modern day experience.

Translation and The Rise of Subtitles

With new production companies appearing in America and Europe, the inevitable question of translation for export markets arose. Intertitles presented no obstacle as they could be easily removed, translated then filmed and reinserted, whilst sometimes the translation issue was resolved by having actors re-voicing or ‘live dubbing’ the dialogue from behind the screen. In France and Japan especially, foreign films, i.e. mostly American, would be shown with an accompanying on-stage interpretive commentator – the Bonimenteur 16 in France and the Benshi 17 in Japan. The interlocutor explained the story and translated the intertitles, interpreted the on-screen action and in Japan in particular, imaginatively voiced the actors’ silent dialogue.

However, from as early as 1909 attempts had been made to complement silent films with what a modern day audience would recognise as subtitles. The first known experiments 18 included using a sciopticon (similar to a magic lantern) to project text onto the screen; a method that relied on the projectionist displaying glass slides precisely in time with the actors’ silent dialogue, whilst trying not to scorch his fingers! A similar approach had printed text on a contiguous film strip, dubbed ‘linetitles’ in Denmark 19, although once again this relied on absolute synchronisation, but as if to compound the problem still further, the projected text (slide or film strip) was often indistinct and difficult to read.

One truly novel idea for illuminating on-screen dialogue, which doesn’t quite fit into the category of either Intertitling or Subtitling, was devised by the former leader of the (American) Jewish Congress turned playwright, Abraham S. Schomer 20, who, in 1915 (following a series of successful plays) gave up his New York law practice to write for motion pictures. Valiantly attempting to break away from the obvious limitations of intertitling, he wrote, directed and co-produced The Chamber Mystery 21, released in 1920, which combined intertitles with in-frame word balloons added in post-production. Sadly for Schomer, those comic book add-ons failed to capture the imagination of the viewing public and his film is largely overlooked in the wider history of cinema; the irony being that modern day computer generated text can be programmed to appear anywhere on-screen and even track a character’s movements, so perhaps Schomer was actually less of a misguided eccentric and more a misunderstood visionary.

Around the time that Schomer was experimenting with his word balloons, a young, aspiring concert violinist, Herman G. Weinberg 22 was rearranging symphonic scores of German silent films for the string quartet at the Fifth Avenue Playhouse in Manhattan. Being fluent in German, he also started to translate the first talking pictures from Germany, which lead him into a new career that would eventually span 60 years, during which he subtitled over 300 films and wrote extensively about cinema. In an interview with Weinberg, about his days as a subtitler, he commented:

“At first we tried the technique used for silent pictures. Every few minutes there would be a full-screen title…But that didn’t work because there were always a few people who could understand German, and they would laugh at the spoken jokes in the film. Everyone else got annoyed because they thought they were missing something”. 23

Later, after acquiring a Moviola (a machine that allowed an editor to view the film whilst editing), Weinberg cautiously tested its potential for displaying text within the moving images, at the bottom of the screen, noting the audience “Didn’t drop their heads, they merely dropped their eyes” 24. Unfortunately, whilst Weinberg had noticed the natural, unconscious reaction of the audience, this same realisation would inevitably become the basis for ideological abuse within certain authoritarian regimes to come, for an audience largely unfamiliar with a foreign language tends to accept the ‘translation’ skills of the subtitler without question.

On a lighter note, an amusing tale is told 25 about Weinberg’s dry wit and his ingenious approach to circumventing censorship. Deliberating over how to translate a particularly offensive comment in a French film and knowing that the accurate translation would never be passed by the American censors, Weinberg, like Schomer before him, found inspiration in the comic book approach to swearing and his solution was – “XZ%!X”. Needless to say, but his ‘translation’ passed without comment.

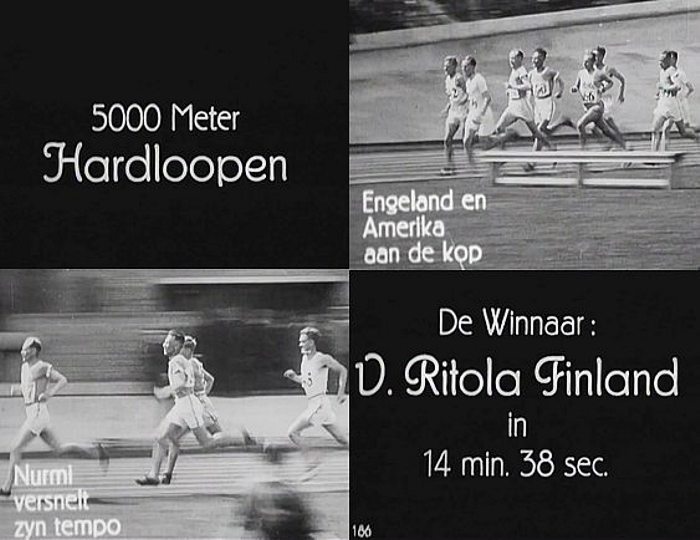

Stepping back a few years to 1924, the German film producer Wilhelm Prager 26 released a sports documentary Wege zu Kraft und Schönheit (Ways to Strength and Beauty 27), which featured a combination of intertitles and on-screen titles to add commentary and name the competing athletes. Although not a new idea at the time, this nevertheless indicated a prevailing move away from solely relying on intertitling. Prager would go on to re-edit a controversial, unfinished Italian made documentary of the 1928 Olympic games, entitled La IX Olimpiade di Amsterdam 28, but operating under budgetary constraints, Prager deferred to his previous method – creating both an Italian intertitled version and a Dutch version with intertitles and on-screen titling.

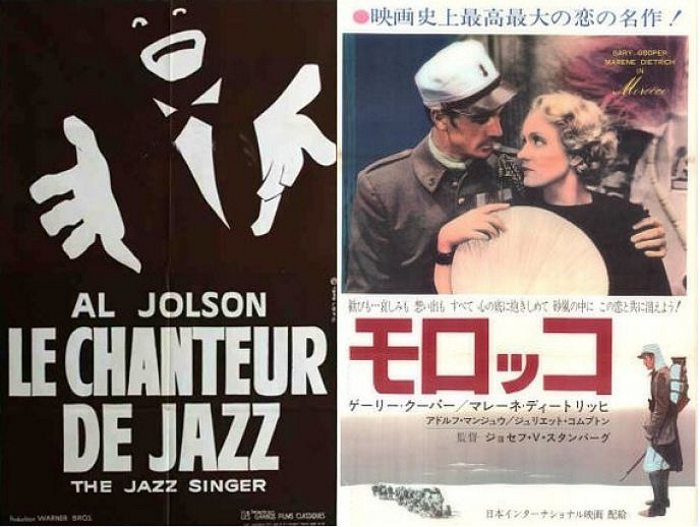

With Weinberg’s Moviola trials, Prager’s on-screen titles and the 1927 release of Warner Brothers’ (semi) talking picture The Jazz Singer 29– creating an instant media sensation at its premiere and thrilling the viewing public – the writing was finally on the wall for intertitles.

The Advancement of Subtitling

As Hollywood’s talking pictures began to dominate the world cinematic stage, this new phenomenon gave a much needed impetus to the improvement of subtitling for foreign markets. Building on the techniques used for Prager’s documentaries and American films such as the 1925 Clara Bow star vehicle The Plastic Age 30, an optical process was developed, in which single subtitled frames were held in position whilst the film negative and the positive print strip were fed forward and exposed at the same time. The result was an improvement in the legibility of subtitles and on the 26th of January 1929, The Jazz Singer, with French subtitles, opened in Paris, followed by a Danish subtitled release of The Singing Fool, in Copenhagen on the 17th of August 1929 31. The public’s response was, however, less than enthusiastic at first, with the subtitles being considered ‘annoying’ by some 32.

Meanwhile, in the land of the rising sun, two masters of Japanese subtitling, Shimizu Shunji and Tamaru Yukihiko 33 were experimenting with subtitles projected to the side of the screen. Whilst Shimizu is generally credited with inaugurating subtitling proper in Japan, it was Tamaru who created the subtitles for Josef Von Sternberg’s 1930 film, Morocco 34 (released in Japan in 1931), the first Hollywood film subtitled for a domestic Japanese audience, although Tamaru didn’t bother to translate any of Deitrich’s songs in the film. A widely held opinion among native Japanese subtitlers at the time, expressed here by Shunji’s contemporary, Okaeda Shinji 35, was that “The less words a film has the better”(sic) 36, so presumably that opinion also applied to foreign songs! Tamaru introduced Shimizu to Paramount Pictures, which engaged him to prepare subtitled American newsreels for distribution across Japan during the 1930s and ’40s, until American films were eventually banned in Japan with the outbreak of World War 2. Post-war, Shimizu went on to mentor the renowned and occasionally controversial subtitler, Natsuka Toda 37;later sacked 38 by Stanley Kubrick following her reductionist, toned down translation of his profanity laden 1987 film Full Metal Jacket.

Whilst Hollywood extended its hold over the film industry from the 1930s to the 1950s ‘Golden Age’, in Europe during that same period advances in subtitling techniques were developed in Norway, Sweden, Hungary and France 39. It was the Norwegian/Swedish film laboratories Filmtekst in Oslo, Ideal Film in Stockholm and the Paris based Titra-Film 40 that monopolised the subtitling market from 1933, the latter maintaining its prominent position right up to the modern day – and it all started in 1930 when a Norwegian inventor named Leif Eriksen patented a mechanical method for stamping text directly onto the film strip. Quoting (with permission) from the Swedish writer and lecturer, Jan Ivarrson’s article ‘A Short Technical History Of Subtitles In Europe’ 41,

[Eriksen began by] ‘…first moistening the emulsion layer to soften it. The titles were typeset, printed on paper and photographed to produce very small letterpress type plates for each subtitle (the height of each letter being only about 0.8 mm)…’, [which would then be pressed into the emulsion layer to create the desired subtitle].

Then, in 1932, a chemical process was simultaneously patented by the Hungarian and Norwegian inventors, R. Hruška (in Budapest) and Oscar I. Ertnæs (in Oslo), using heated printing plates pressed against the emulsion side of a wax or paraffin coated, finished film copy. The coating melted and exposed the emulsion beneath. The film was then washed with bleach to dissolve the exposed emulsion, producing legible white letters when projected onto a screen, although the edges were slightly uneven owing to variations in the overall process 42.

Three years later a thermal process was patented by another Hungarian, O. Turchányi, ‘… whereby the plates were heated to a sufficiently high temperature to melt away the emulsion on the film without the need for a softening bath’, but there was an inherent problem with this process, as with Eriksen’s earlier approach – both were difficult to control and the resultant subtitles were not always legible. During the late 1940s, in Britain, the Rank Organisation 43 briefly experimented with subtitles etched onto glass plates that were displayed, via a projector, at the bottom left hand corner of the cinema screen, although it was an improved version of Turchányi’s process, and the earlier chemical processes of Hruška and Ertnæs, that continued to be used in Europe and also remained the dominant subtitling process across parts of Asia and South America even into the late 1990s 44.

On her website 45, the French subtitler, Maï Boiron describes her duties during the days of chemical subtitling in the early 1990s. “Using a microscope, I’d proofread each tiny zinc plate used to etch the subtitles onto the film, frame-by-frame”. A task that required a very steady eye! Boiron would later join Titra-Film in Paris, which, along with the Laser Vidéo Titres’ (LVT) entrepreneur, Denis Auboyer 46 had been developing laser etched subtitling since the mid-1980s. However, there were early problems during testing of the new technology, with the laser burning through both the emulsion and the film and yet, with adjustment, the ‘burn’ turned out to be an advantage. Quoting Monsieur Auboyer:

“It is like if you have a cigarette and a piece of white paper. You make a hole in the paper with the cigarette and around it there is a black circle. This is what we have around the subtitles, so you can see them even when the background is white.” 47

Auboyer’s calling card was LVT’s subtitling of Clint Eastwood’s Bird for the 1988 Cannes film festival, stating “While this was not our first film, we consider it one of the most important for our reputation” 48 and thus the old methods of manual typesetting, chemicals baths and hot-plates finally became redundant in the European market. Hollywood adopted the same laser process and by the 1990s laser titling became the industry standard, with subtitling for domestic American cinema audiences predominantly done by companies in Los Angeles and London; now known in the professional world of titling as the L.A.-London axis.

Subtitling for Digital Cinema

The development of new technology is ceaseless, as the story so far has shown and whilst Maï Boiron was proofreading those tiny zinc plates, a revolution was underway in America. 1992 saw the first public demonstration of digital cinema 49, with further public demonstrations in 1998, 1999 and 2000 50; and in 2001 the European Digital Cinema Forum (EDCF) 51was established to discuss the progression of digital technology and in particular, high quality subtitling.

“Subtitles are usually the last thought on anyone’s mind when planning a media package for mass distribution…The need for accurate, intelligent and compelling storytelling is of paramount importance…[but]…the off-putting feature of subtitling is the cost. There is an outside service premium that cannot be avoided; an expertise that cannot be replicated by the likes of online translator sites”. Mazin Al-Jumaili. Head of Operations. Visiontext and lobbyist for EDCF 52.

Two years later, on the 3rd of November 2003, Texas Instruments released its ‘Subtitle Specification (XML Format) for DLP Cinema Projection Technology‘ 53 and over the next ten years, twenty digital subtitling format patents were applied for in America, Europe and Japan 54. By 2010 the Digital Cinema Naming Convention (DCNC) 55 was developing coding for digital cinema film packages to identify, amongst other aspects, the subtitling element. An example is as follows:

MOVIE TITLE-GL_FTR_F_FR-EN_FR-GB_51-FR_2K_ST_20070115_FAC-i3D_OV

What looks like a meaningless jumble of letters and numbers to the average person can be deciphered at a glance by the receiving projectionist. A full explanation of the DCNC coding can be found in publicly available documentation 56, but for the purpose of this article only the entry ‘FR-EN‘ (bold added for emphasis) is directly relevant as this indicates that the sample film is in French (FR) with English subtitles (EN).

There are two methods for including subtitles with a digital film. The first has ‘open’ subtitles, which are coded into the digital format and so cannot be removed or switched off. The second has ‘closed’ subtitles, which are included as a separate file so have to be selected via the computer software and then the digital projector automatically synchronises the subtitles with the film. The latter method is a little like a super hi-tech version of the old sciopticon, except far more efficient and with no danger of scorched fingers!

That’s (not) all Folks!

With the recent developmental interest in Augmented Reality (AR), perhaps it’s not surprising that, sooner or later, someone, somewhere would take a look at a simple pair of glasses and think “That gives me an idea!” and sure enough, in 2009 at the Sony Consumer Electronics Show 57, the actor Tom Hanks demonstrated Sony’s prototype for subtitle glasses. By 2012 the glasses were undergoing widespread testing in cinemas across America and Europe, whilst in Japan the Seiko Epson Corporation had been developing a similar product during 2011 58. Although the latter’s end goal is the AR market, its first subtitling trials were conducted in partnership with the Japanese New National Theatre Foundation in 2014. Both inventions use Wi-Fi to receive a signal from the theatre’s server and then display the subtitles on the inner surface of the lenses.

Meanwhile, in Britain during 2013 and 2014, the ex-teacher turned inventor, Jack Ezra was developing what he described as an ‘Off-Screen Cinema Subtitle System’ 59 for the deaf and hard of hearing. In comparison to Sony and Epson’s products (expensive, easily damaged if dropped and [allegedly] uncomfortable when worn for long periods) Ezra’s system is unique and considerably cheaper.

“Our system places a special ‘inconspicuous’ display along the bottom of the movie screen, which looks blank. This way it does not distract the general audience…For those who want to see the subtitles, they simply slip on a…lightweight, pair of glasses, which enables the viewer to read subtitles on our display, which shows large, clear captions in sync to the movie” Jack Ezra. 3D Experience 60.

Whether it’s Sony’s, Epson’s or Ezra’s system that eventually prevails, only time will tell, but there is a delicious irony to this tale. In the early days of cinema, silent films were ‘democratic’ insofar as they could be enjoyed by the hearing and the hearing impaired alike, for intertitles didn’t discriminate between the two. With the advent of talking pictures, the hearing impaired were largely marginalised; cut-off from a source of entertainment they once enjoyed. Early subtitling was sporadic and undisciplined with no industry guidelines as to what should or shouldn’t be translated, so, especially in the case of Japanese subtitling, some scenes were left partially translated, or not translated at all 61. Now, with the development of systems to aid the hearing impaired, this return-to-the-roots approach may well herald the future of subtitling for everyone. How times, and subtitles, have changed.

For the moment though, when next watching the latest Korean action movie or French romantic comedy at the cinema, spare a thought for those early inventors, innovators, eccentrics and entrepreneurs who laid the foundation for the technology now used to display those crisp, white letters at the bottom of the screen. After all, where would foreign film translation be without them?

Works Cited

- ‘The Invisible Subtitler‘. Arc Pictures. 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pz75i6EsOto ↩

- ‘Film History: An International Journal’. Vol.23. Issue 1-2. Pp 81-94. ↩

- The New Historical Dictionary of the American Film Industry. Anthony Slide. Routledge. 2014 ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinetoscope#Kinetophone ↩

- Barnes, John. History of Victorian Cinema. The Beginnings of Cinema in England. London: David & Charles. 1976. Also see: http://www.victorian-cinema.net/paul ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._Stuart_Blackton. Also see: http://www.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2b9f189138 and https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCmQyoUgvbwfTqLTvW4uaJfQ ↩

- The British Film Catalogue. 1895-1970. London. David & Charles. ISBN 0-715305572-4 also see: http://www.britishpictures.com/books/catalogue.htm ↩

- http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0250634/ ↩

- Hepworth, Cecil M. Came the Dawn. London. Phoenix House. 1951. Also see: http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/450004/ and: http://www.surreybrass.co.uk/SB/things/hepworth.htm ↩

- Short Film. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65rGf2swdtU ↩

- Penguin Film Review. 8th of April 1948. ↩

- Short Film. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILDHYYsC-g0 ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H_bAxDXEM5A ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CZCsBCio41k ↩

- http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0233471/ Also see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4QwvGXIyfoQ ↩

- https://forum.wordreference.com/threads/bonimenteur.2605457/ (French language forum) ↩

- The Benshi Tradition. http://www.altx.com/interzones/kino2/benshi.html ↩

- Chee Fun Fong, Gilbert, Kenneth K.L. Au. Dubbing and Subtitling in a World Context. Chinese University Press. 2009. ISBN 9629963666 ↩

- Gottlieb, Henrik. Screen Translation: Eight Studies in subtitling, dubbing and voice over. Centre for Translation Studies. Department of English. University of Copenhagen. 2005 ↩

- https://dcairns.wordpress.com/tag/abraham-s-schomer/ ↩

- http://www.silentera.com/PSFL/data/C/ChamberMystery1920.html ↩

- http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0918116/ Also see: https://www.nytimes.com/1983/11/08/obituaries/herman-g-weinberg-writer-and-foreign-film-translator.html ↩

- An interview with Herman G. Weinberg. ‘A Wee corner of Showbiz’. The Emporia Gazette. Emporia. Kansas. Saturday 6th August. 1960. p 2. ↩

- Weinberg, Herman G. A Manhattan Odyssey: A Memoir. New York:Anthology Film Archives, 1982. p108 ↩

- https://www.nytimes.com/1983/11/08/obituaries/herman-g-weinberg-writer-and-foreign-film-translator.html ↩

- https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0695114/ ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ways_to_Strength_and_Beauty ↩

- https://flyczba.wordpress.com/category/intertitles/ See: ‘Words on images: the Olympic moment (1928) July 2, 2012’ entry. ↩

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0018037/?ref_=nv_sr_2 ↩

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0016226/?ref_=nv_sr_1 ↩

- Ivarrson, Jan. http://www.transedit.se/history.htm ↩

- Nornes, Abé Mark. For an Abusive Subtitling. http://academic.csuohio.edu/kneuendorf/frames/subtitling/Nornes.1999.pdf ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shunji_Shimizu ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morocco_(film) Also see: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0021156/ ↩

- Nornes, Abé Mark. For an Abusive Subtitling.p21 http://academic.csuohio.edu/kneuendorf/frames/subtitling/Nornes.1999.pdf ↩

- ibid. P5. Footnote 15 ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natsuko_Toda Also see: http://www.tokyojournal.com/sections/translation-subtitling/itemlist/user/65-natsuko-toda.html ↩

- Natsuka sacked by Kubrick. Nornes, Abe Mark (2007). Cinema Babel: Translating Global Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 216-217 ↩

- Ivarrson, Jan. http://www.transedit.se/history.htm ↩

- http://www.titratvs.com/fr French language site ↩

- Ivarrson, Jan. http://www.transedit.se/history.htm ↩

- ibid ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rank_Organisation ↩

- Ivarrson, Jan. http://www.transedit.se/history.htm ↩

- http://www.maiboiron.com/-About-me- ↩

- https://patents.google.com/patent/FR2855884B1/en?inventor=Denis+Auboyer Also see: http://www.nytimes.com/1995/03/06/business/worldbusiness/06iht-title.html ↩

- ibid ↩

- ibid ↩

- http://tech-notes.tv/Dig-Cine/Digitalcinema.html ↩

- ibid ↩

- http://www.edcf.net/edcf_docs/edcf_mastering_guide.pdf ↩

- http://www.edcf.net/edcf_docs/edcf_mastering_guide.pdf p18 ↩

- http://www.deluxecdn.com/dcinema/support/ti_subtitle_spec_v1_1.pdf ↩

- European Patent Office. Applicant: Thomson Licensing 92130 Issy-Les-Moulieaux (FR).Patent Application EP 2 938 087 A1. pp.7-8. ↩

- http://digitalcinemanamingconvention.com/DigitalCinemaNamingConvention.pdf ↩

- http://digitalcinemanamingconvention.com ↩

- https://www.sony.com/en_us/SCA/company-news/press-releases/sony-electronics/2009/sir-howard-stringer-sony-chairman-and-ceo-presents.html ↩

- https://files.support.epson.com/docid/cpd4/cpd40542.pdf ↩

- http://www.3dexperience.co.uk/2015pages/subtitles.html ↩

- https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/off-screen-cinema-subtitle-system#/ Also see:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b6uDWl4wVFg ↩

- Nornes, Abé Mark. For an Abusive Subtitling. p.25 ‘The Champ’ http://academic.csuohio.edu/kneuendorf/frames/subtitling/Nornes.1999.pdf ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Excellent and very accurate article on the history of subtitling.

Snell. Thank you for your glowing praise. I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface of the surface (there was so much I had to leave out). As you can see from my reference list, there is a world of information out there.

Let us give thanks to subbers, especially those that translate foreign languages to local languages!

Bright. As an amateur subtitler I couldn’t agree with you more. Subtitlers really are the unsung heroes of post-production and yet we rarely even know their names.

Very interesting indeed. I am from Italy, I watch everything I can. and I have to admit that subtitles help me a lot! I love documentaries, but unfortunately very few have subtitles…why?

Ara. Hello to Italy from the UK! Perhaps the reason why documentaries aren’t subtitled as often as mainstream cinema films and TV programmes/series is simply down to popularity and budgetary constraints. You picked up on a subject I hadn’t considered so it could be worth investigating. Thanks for the suggestion.:)

I had a brief encounter with subtitling for many years back. It’s a tricky business-cross-lingual and cultural translation with serious space and time constraints. It’s a testament to these people’s hard work that you can understand anything at all.

What I mainly enjoy is seeing subtitles for speakers of the same language, but from different regions or cultures. You get this a lot with French, especially subtitles of Québécois productions done for distribution in Europe, becuase Quebecers have a whole other slang/vocabulary, and often utterly incomprehensible accents. It’s fun to see how French subtitlers try to come up with local equivalents for “crise du tabernacle!” or “j’ai fait d’mon best d’avoir du fun avec mon chum” or “j’ai les dents du font qui baignent!”

Aleen. Excellent point with regard to translating Québécois slang into ‘French’ French! As an amateur subtitler I have to admit one of my bugbears is poor quality fansubbing in which the ‘translator’ can’t even be bothered to attempt a translation. I recently downloaded a poor fan sub (from a certain well known site) for the Korean drama film ‘1987. When The Day Comes’, in which, for reasons I still can’t fathom, those lines that the subber couldn’t translate into English were machine translated into Malay! That damned G**gle translate has a lot to answer for!

Great article, I never even considered how storied the history of subtitling in film must be. Its one of those things a lot of people take for granted, so thanks for drawing attention to an under appreciated and necessary enterprise!

alexbolano92. Thank you for your positive feedback. There is more to come.

Great analysis! I confess, I never understood the widespread distaste for subtitles. Maybe I read fast, but I never found them distracting. Besides, if modern actors insist upon mumbling their lines, for home viewing at least, subtitles are going to be a necessity.

Allie Dawson. Thank you. Yes, I, like you, have never had a problem with subtitles, but then I grew up watching subtitled films so became used to reading and watching at the same time. I find it amusing that some youngsters these days will complain about subtitling and yet happily watch TV programmes with near-constant scrolling text along the bottom of the screen and an image littered with screen idents, promos for ‘what’s on next’ and who knows what else. Regarding your point about mumbling actors, I confess one reason why I started subtitling is because my mother is very nearly deaf and has problems with on-screen mumblers so I’ve decided to teach myself how to create SDH (subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing)…and she is my guinea pig! Thanks again for your comments.

I’m a Brazilian subtitler and appreciate everything with this post.

Meek. Hi to Brazil and thanks for your feedback. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I believe that in Brazil if a viewer finds mistakes with subtitling in a film transmitted on TV, he/she can complain to the authorities and will then receive a corrected version of that film free as compensation. Sounds like a great idea to me!

Bad subtitles are just as bad as bad actors or bad original scripts. And people do not realise that good subtitles are just as important. What a shame! I hate bad subtitles. They ruin my enjoyment.

Aura. I couldn’t agree with you more. One of the problems is ‘outsourcing’ of subtitling, which means no control over who creates the subtitles or how they do so. I, for one, can’t stand machine translation, even when it’s (almost) accurate as it lacks the soul and flavour of the human touch. There’s a rhythm to human speech and a decent subtitler will always work within that rhythm to create subtitles that flow naturally. Bad subtitlers just hammer out any old nonsense, frequently littered with anachronisms and American slang (no offence intended towards native born Americans) that has no place in the subtitling. I recently watched a Korean drama series and in one scene, one prosecutor was asking another if he would like to join him for dinner. As we know, Koreans have a very formal way of addressing each other professionally, but the idiotic fansubber had translated the interaction as: ‘Hey dude, wanna go get a burger’. I was so frustrated I almost threw my boot at the screen!

I wish the companies get conscious that the best script could be completely ruined with a bad subtitle, and sometimes, ruined the entire film.

Stasim. I agree with you. If you want to see a great example of truly dreadful subtitling then go to You Tube and search for ‘Backstroke of The West’. It’s a Chinese, pirated copy of the 3rd Star Wars film and the subtitling has to be seen (or read) to be believed. It’s actually so bizarre that it’s generated a fan following and there is even a fan dubbed version available, which uses the ‘Chinglish’ script. Allah Gold! (no spoilers). Cheers.

I’m so pleased you mentioned this as I always think of it as an example of bad subtitles.The changing of Darth Vader’s “Noooooo!” to “Do not want!” cracks me up even though it’s by no means the strangest translation of the script.

midado. Great to see that you got my reference. Yes, ‘Backstroke of The West’ truly is a category of its own when it comes to bad subtitling. It makes me wonder how on earth they translated ‘Star Wars’ into ‘Backstroke of The West’ when the words ‘Star’ and ‘Wars’ are there on the screen to begin with. They only had to copy them! Similar happened with a Chinese bootleg of ‘Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone’, with ‘Harry Potter’ being translated as ‘Harry Ceramic’ (at least that was half correct). Even if nothing else, there should be some sort of Golden Raspberry type award for the worst subtitle track of the year/decade etc – I’m sure Vader’s “Do not want!” would be a worthy entrant. There is another article to come and I have a few more choice gems to share with readers.

Great post. I am not hard of hearing, but I do put subtitles on anyways incase i can’t make out whats happening as our tv has quite a low volume.

Fisk. Thanks your your comments. Yes, it does seem that the use of subtitles is becoming more frequent. You mentioned your TV having a low volume; I thought about how whenever we see a TV on in a public arena (stations, airports, cafes etc) they always display the subs to counter the surrounding noise. Subs are part of our everyday life, more so than many people would realise.

Typo – thanks for your comments, not thanks your your comments. Ugh, I need another coffee!

In Spain, there’s a tradition of dubbing all the foreign films into Spanish. It dates back to the dictatorship of Franco, that in 1940 stablished that all movies should be dubbed into Spanish.

Then the dictatorship ended and some cinemas chose not to dub the movies and run them in their original languages with subtitles. Nowadays, these are the only cinemas that I know of that offer any kind of accessibility services.

Rachelle. Thanks for your comments. Yes, I am aware of the Franco-era tradition of dubbing, in fact I made a subtle hint about similar in my article. I didn’t follow-up on that because I was focusing solely on subtitling and wanted to avoid becoming ensnared by the ‘Which is best: Dub or Sub’ debate. For ideological reasons, dubbing has been used by several authoritarian regimes across the years. Actually, that in itself, could make for a fascinating article – fancy giving it a go? Cheers 🙂

The film industry is forever devising new ways to capitalise on technological advancements.

kikk. Nice one. I see you read between the lines where I included Sony’s use of Tom Hanks to endorse its subtitle glasses. Well spotted.

What would consuming film be without subtitles. We use the subtitles in English all the time due in part to words being slurred, in part to regional accents being difficult to follow and principally due to poor hearing.

Chet. Excellent points indeed. SDH in particular is on the increase and I’m sure that soon it will be common place and widely accepted as the norm. I thought Jack Ezra’s off-screen idea was brilliant.

China does this too. Not sure when they started, but certainly more than ten years ago. The reason more or less the same, I think – literacy promotion.

Rinydays. Yes I believe it is quite a recent development, in terms of film making anyway. During my research I came across several documents about the Chinese authorities translating between different regional accents for different film audiences, using the subtitles as a way to increase literacy. As it wasn’t directly relevant to my article I didn’t record the URLs, but the information is out there somewhere. I also discovered an interesting document about the translation of English swear words into Cantonese. If you’re interested here’s the link: https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/meta/2004-v49-n1-meta733/009029ar/

Nice post. While subititling may be an art and a profession, increasingly this art is undergoing another evolution.

Pugh. Thanks for the praise. Yes, subtitling is indeed undergoing a revolution even as we speak (or write). Language evolves and so too must those who translate and subtitle, but I doubt machine translation will ever be able to truly ‘understand’ human colloquialisms, idioms and ever changing street slang.

It is a shame that the law does not require all published videos to have subtitles. It would help tremendously the public, and costs very little.

Zada. In principle I agree with you. The only downside I can see to it though is the danger of certain governments establishing officially recognised subtitling that could be open to ideological abuse, albeit subtly. The odd turn of phrase or nuance can alter the meaning of a sentence, sometimes without the viewer even noticing and so influence a viewer’s opinion about a particular subject. As to the cost – well it does actually cost a fair bit to employ a professional subtitler, which is fair enough as professionals are just that – professionals; and they’re more than just a translator. I’d recommend watching ‘The Invisible Subtitler’ on You Tube for the inside track. A very good and informative documentary. You may also be interested to hear that last year a Dutch court ruled fansubtitling to be illegal (see: https://thenextweb.com/insider/2017/04/21/court-rules-fan-subtitles-tv-movies-illegal/), ruling that it’s a copyright infringement. In my opinion this is typical jack-boot thinking from the authorities. A better approach would have been to offer fansubbers the chance to work legally for Dutch TV or similar and so create more jobs.

Wow! I had not really thought about the history of this! Really interesting, thanks for sharing.

SaraiMW. You’re welcome and thanks for the feedback. I bet you’ll never look at a subtitled film in the same way again! 🙂

I was really lucky to be born in one of the few european countries who very rarely dubs TV shows/movies that are not directed to small children. In fact, I’m fairly certain I started understanding english by crossreferencing what I was hearing on TV and what I was reading.

gedonga. Thanks for your feedback. As I was researching subtitling I came across quite a lot of fascinating information about the European countries that favour either subbed or dubbed programming. Interestingly those with a more Nationalistic history still favour dubs over subs, whereas the more enlightened Scandinavian bloc generally favours subtitling. There are exceptions, of course, but I think it would make a fascinating subject to study in depth, especially when considering how subtitling may, or may not, help to develop foreign language skills.

Always remember many moons ago watching Lethal Weapon 2 in a cinema in Brussels. It was in English, but with subtitles. Odd to hear an audience laugh before the actor said the punchline.

Witt. That was bizarre! Mind you, I know what you mean and that’s one of the issues a professional subtitler has to address – the timing of the subs so as not to give away a punchline before it’s spoken. There are a few crafty ways around the problem, but it can lead to some real headaches when translating jokes from Japanese (for instance) as the whole sentence has to be reworked and quite often it’s easier to create a new joke that loosely follows the theme of the one in the film or add an amusing comment to the same effect.

Thank you for the history lesson! It is interesting that deaf/hard of hearing adults who could read English had full access to silent films; but struggle for access now. My daughter, who is deaf, has to wait for the dvd to come out to see a film with captions, or keep her eye out for the rare special open caption showings. The internet needs captions, too!

Sars. Thanks for your reply. I’ve come to appreciate the subtleties of specifially subtitling for the hearing impaired viewer since I’ve taken on more SDH commissions, as well transcribing audio descriptive tracks for the blind. Both Netflix and You Tube have been supplying closed captioning with videos for a while now, but the quality varies considerably and, with You Tube in particular, they are too often machine translated and haven’t been quality control checked. It must be very frustrating for your daughter. If a system such as the one planned by Jack Ezra were to be implemented in cinemas then it would solve the issue very easily and cheapily. We can but hope.

Forget about subtitles. Bring back 70’s kung-fu bad dubbing.

rubio. LOL, I think you’ve come to the wrong page! Anyway, yes I remember those classic days of truly awful dubbing as well. I was at school in Hong Kong during the 1970s. The old Run-Run Shaw studios used to churn out their films by the dozen every month. If you want a good laugh then do a search for Dr Craig D Reid, probably the most knowledgeable westerner to write about the 1970s Kung-fu films. I can’t recall exactly where I saw it, but during my research I got a little distracted and ended up reading a very amusing article by Reid about working with several drunk Australians during a dubbing sequence and some of the antics they got up to. I don’t know…Australians, beer and Kung-fu – what is the world coming too. LOL. Enjoy and thanks for bringing back a few old memories. Ahh, they don’t make ’em like they used to.

Sub-titling is very difficult. I’ve done a lot of translation and some interpretation and tried subtitling couple of times (for my own amusement) and would judge that sub-titling is the most difficult of the lot due to the time and space constraints (as against translation) and the fact it’s ‘permanent’ (as against interpretation).

And, from what I’ve heard, it’s very badly paid for what is a very skilled job.

Duttnou. Very true. Subtitling is part-translation, part-adaptation. Time and space constraints are difficult to work within, but when you consider that an average person reads between 12-16 characters a second (although I expect that those of us who read a great deal can probably process more than that), then the maximum of 36 CPS per line guideline makes sense. One of my bugbears is when a spoken line runs over a cut and stops short, making it difficult to sub that line without leaving an orphan on screen for a second or two. It’s especially difficult when there’s a long gap (3 seconds or more) before the next line is spoken as it hinders a tidy concatenation of the lines. Damn, I’m talking shop, sorry. I’d recommend watching ‘The Invisible Subtitler’ – a fascinating documentary that exposes the exploitation of modern day subtitlers. Thanks for your comments.

Millions of words are written about film every year, but few about the subtitler’s craft. Thanks for writing about this.

Livia. Thanks for your feedback. Greatly appreciated. 🙂

With subtitles, we can learn more about English speaking in other country’s accent. This really helps a lot especially if you are a traveller who travels very often to other country.

dion. Yes, to some extent you are correct, although it’s rare that subtitles will present a completely accurate ‘translation’ of the original script. The aim is really to come as close as possible to the meaning of the source language whilst still keeping the rythymn intact. It can be difficult at times. It’s also best to use a generic English that can be understood by any English speaker. Thanks for your input.

Why they aren’t at least on children’s films and programmes has been a long running mystery.

PLAZE. Good point and to be honest, I don’t have an answer for you. That would be worth investigating.

This is actually really interesting – I’d assumed all subtitles were done by someone watching the program and typing the speech out =P I appreciate them a lot more now!

Cortes. Well, you’re not that far off actually. In the early days of subbing it was literally done with a stopwatch in one hand and a note pad in the other, marking the timing (termed ‘spotting’) and writing the lines out by hand. Those would then we transcribed by a typist. Alternatively it could be done by counting the frames – approx 24 frames in a film equals one second of screen time. Of course there is a lot more involved in the whole process and it would take another article to detail everything. These days all that can be done with software (I use a programme called Aegisub) and it’s a lot quicker, but, in effect, the actual process hasn’t really changed, although at least we don’t have to worry about hot metal presses anymore. Cheers and I’m pleased I aroused your curiosity.

Thanks for this very clear history on subs.

Shiloh Lira. And thank you for your reply. Greatly appreciated.

Interesting read, good writing.

Life is difficult without subtitles, particularly if you need to mute the TV so the kids can sleep, or if you fancy Korean drama but does not speak a Korean word.

Manny. Thanks for that. Do I sense another K-Drama fan? I have to admit that even though I don’t bother with TV in general, I do enjoy a good K-Drama. ‘Queen of Mystery’, ‘W -Two Worlds’, ‘Tunnel’, ‘Witch’s Court’…I could go on. I appreciate your feedback 🙂

Being a translator myself, I always write my name in the subtitles and insist that the customer mentions my name as a translator when loading my subtitles somewhere in the Internet. And I think if more translators would do this, our job will be much more respected. So, my dear translators colleagues, be more harsh and strict to your customers and don’t understate yourselves. Our job is one of the most important ones, so bare this in mind, respect your work and let others respect it.

Mast. Here, here (applause). I’m only an amateur subtitler, so not in your league (yet), but I do agree with you. The work is often unappreciated and so many people have no idea just how many hours it can take to produce good subtitles. I’ve just done my first semi-professional job and, like you, have insisted that my name is included in the credits. Thanks for your comments from the inside of the profession.

Film and video have a promising future, but it also has an intriguing past and I think you captured it really well. <3

Ha Witt. Thanks, that’s really kind of you. Have a coffee on me 🙂

I like the idea of learning a language via subtitles.

Normal everyday speech is full of metaphor and popular references and when I first saw English shows and films with Norwegian subtitles, I was struck immediately by how little of what appeared on the screen was a literal translation.

I cannot think of a quicker way to learn to speak a language colloquially, than by seeing popular television programmes in ones own language with subtitles in the language to be learnt.

Marlyn. Yes, as I’ve mentioned to others, it’s a fine line between translation and adaptation, but language learning via subtitling has proven to be very useful. If you watch ‘The Invisible Subtitler’ then you’ll see how the Indian authorities have been using subtitled song and dance programmes on TV to increase literacy rates, with good results! Even I have started to pick up the odd Korean phrase from watching Korean drama series and films. It doesn’t take that long.

I truly appreciate the work these people do. I subtitled two old Zarah Leander films into English and it took me weeks. The results were nowhere near as deft as what we see on the TV or in cinema as I am not a professional although I work with and in several foreign languages.

So hats off to these agencies who make sense of excellent foreign work for us.

Ludwig. I started in much the same way, re-subbing Japanese films I enjoyed that had poor subtitles. Using only my basic level Japanese, two phrase books and a dictionary, I made a halfway decent cock-up, but learned from my mistakes. It’s great that you can work in several languages though, you have my respect for that. Thanks for your feedback.

Wow- really interesting – thanks!

juliadigiacomo. Thanks, it’s always nice to know someone appreciates a piece of work. I’m pleased you enjoyed it 🙂

This is so interesting – thanks!

…and thanks again!

First, I want to thank you for your article. My favorite part of the article is your treatment of early intertitles and the history of what we now know as subtitling. I understand that there was a lot of information that you were trying to present in a single article. Are you writing your dissertation on the topic of subtitling in early film? I also enjoyed seeing you draw social and cultural observations from the changes we see in the film industry, would love to have seen a deeper treatment of these claims.

Having watched a lot of American films in Russian it makes so much sense for why Russians choose to dub American/French/Indian really all foreign films instead of using subtitles, it is cheaper and less labor intensive. Hiring usually two or even one voiceover “actors” to dub the whole film instead of embedding, translating and editing subtitles. It would be interesting to know how each place such as Great Britain treats foreign films (this would be an excellent follow up article to this one).

OgitheYogi. What a great name! Thank you for reading and appreciating the article. I, in turn, truly appreciate your response.

In reply to the points you’ve raised: Firstly, my original draft was over twice as long as this (heavily) edited final version, so yes, you’re quite correct to recognise that I had a lot of information to impart in a relatively short piece of writing. I’ve learned by previous mistakes, as we all do, and didn’t want the reader to lose interest half-way through, so that’s why I kept the tone quite light, a little jocular and in a narrative form, hopefully pitching it half-way between being informative and entertaining. Secondly, no I’m not planning on writing a dissertation (at least not yet) although with the research I conducted beforehand I could probably write a book on the subject now!

I was tempted to dig a little deeper into some of the social and cultural implications (especially the ideological abuse aspect), but decided to avoid becoming too political as it wouldn’t be appropriate for The Artifice, hence the occasional subtle dig at the change in socially acceptable behaviour etc instead. If you’re at all interested then I would suggest you follow the link to Abé Mark Nornes’ ‘For an Abusive Subtitling’ – especially see his remarks concerning the subtitling of ‘Robocop’ for a domestic Japanese audience, plus the comments about the Japanese dubbed version of ‘The X Files’ TV series.

Your second paragraph has pre-empted some of what I have already prepared for follow-up articles. I’d originally opened this article with a brief overview of what areas and aspects this and the follow-ups would cover, but after some editorial discussion, that was dropped, so I’d rather not give anything away at the moment. Let’s just say that there is more to come 🙂

Great Britain’s treatment of subtitled foreign language films for the cinema has improved greatly over the past ten years or so, but the main problem is still that they are usually only shown on set dates, sometimes barely a couple of times a month. I’m afraid it comes down to cost (doesn’t is always?) and the ridiculous need to maintain profit margins. It seems daft to me that there is a strata of society (the Deaf and Hard of Hearing) who have exactly the same spending power as any of us and yet they are still largely marginalised when it comes to mainstream cinema. Hopefully with systems such as Jack Ezra’s, this will soon change for the betterment of everyone.

Sincerely, thanks once again for your comments and observations.

I used to buy knockoff DVDs when I lived in Asia. It was a lottery in terms of AV quality, and the subtitles often bore no resemblance to the programme/film. As a consequence I’m rather forgiving when mistakes are made in moderns subs.

omm. Hi, I have to admit I did exactly the same when I was in Hong Kong during the 1970s, although back then it was VHS and Betamax tapes. To those readers under 20, yes we did once get our films on tape! Hard to believe it these days when nearly everything is digital. Yes, the AV quality often left a great deal to be desired and I have memories of reading some truly bizarre Chinglish subtitles. As to being forgiving about mistakes made in modern subs (I presume you mean fansubbing), I can’t agree with you. We live in an age in which information is instantly available via the web and there’s no excuse for a fansubber not to produce clean, clear and understandable subtitles. Fansub forums exist for fans to ask advice from others, if they need to. I do! There will always be the occasional slip-up in professional subbing, especially when you consider the pressure they’re under to subtitle a 90-120 minute feature film in 48 hours, so in that instance I will be a little more forgiving, but once again the problem with poor quality so-called professional subbing comes down to the penny-pinching production companies that outsource without first checking that the subbers used are competent. Profit is the driving motive; quality subbing comes way, way down the list. Anyway, thanks for your input. Cheers 🙂

For me, the most annoying part of watching an English-language film with English subtitles is that either:

(A) the sub-titles are considerably delayed, and hence one character’s lines appear on screen while the other character is talking; or

(B) they are displayed slightly too soon – i.e. displaying a whole long line of text, when the actor is speaking fairly slowly. So I can’t help but read the whole thing before the actor has chance to deliver the full line, which I find a bit detrimental to the experience of watching the performance.

Perry. Hi and thanks for your comments. Both problems you mentioned are owing to poor coding. A professional times or ‘spots’ each line so that the on-screen text appears as the actor speaks and not before. With the software that’s available these days, it’s relatively easy to ensure subs are timed correctly before they are hard-subbed, i.e. coded into the finished product. With soft-sub files, i.e. those that come as a separate file and have to be loaded with the film, if small timing errors occur then it’s easy enough to correct that coding in seconds via software. The subtitler can any or all lines then advance the timing by fractions of a second if needed.

Your second point really just highlights the laziness of the subtitler concerned. Again it is easy enough to split a line into shorter sections and sub each one in time with the spoken dialogue. That way a good subtitler will avoid giving away a punchline to a joke, for instance. Good subbing, as I’ve mentioned before, is as much about adaptation as it is about translation.

Digital media has allowed people around the world to access more content, more quickly. And more content means more subtitles, right?

healme. Hopefully so, but only if that means a consistently good quality of subtitles. We can but dream. 🙂

One reason I love The Artifice. Always ready to highlight good things and good writing… !

As a subtitle translator, I enjoyed reading this article so much.

Trangipaniclaire. Wow, that’s some name! Thanks for your praise. You say you’re a subtitler – great! It’s always good to get a professional’s input. 🙂

Tessie. Thanks, that was really decent of you. Much appreciated. Yes, The Artifice is one of my favourite sites.

Really interesting article! I think subtitles are one of those things that are there but are rarely thought about in detail – the process behind them, who does the work, that sort of thing – so I really appreciate your detailed account. Well researched, well structured. Nice one.

BethLJones. Thank you. I’m pleased you found it interesting. Believe me, there was so much more that I could have included, but I thought it best to keep this article short and sweet…ish. There is more to come though.

Most subtitles are executed really well, and I love being able to immerse myself in the non-English cinema.

Palmer. Hi and thanks for the input. Yes, subtitling is a very taxing craft and the really skilled subtitler knows what to translate, what to adapt and, just as importantly, what to leave out. Sometimes less really is more. I’ve just finished doing some subs for a Japanese comedy drama entitled ‘Mix’ and there are scenes in that in which a great deal of information is delivered is a very short space of time (in places as little as 1.06 seconds). That information can be delivered with Japanese characters succinctly, but in English it’s impossible to get the same information across to the viewer in such a short space of time. That’s where the skill of the subtitler comes into play – to know what information is directly relevant to the scene and what to leave out. It’s a juggling act, but the best subtitling work comes across as almost ‘invisible’ and can be read at a glance.

Subtitles are clearly a boon to those who are learning to read and write and should be welcomed but they also help another group of people. I’m talking about the deaf and those who are hard of hearing.

Magen. Very true. SDH is invaluable to the hearing impaired. Its origins may surprise you though. More coming soon 🙂

Was always a bit weird in La Haine hearing them talk about ‘Asterix’ and ‘Obelix’ but seeing them translated as Snoopy and Charlie Brown for the US market.

coraline. Thanks for your comment. I’ve never seen the US market release of ‘La Haine’. The only version I’ve watched was the French language version. Well, you live and learn. LOL. But…Snoopy and Charlie Brown? Noooooo!

I appreciate your descriptions of the various processes that took place in the evolution of applying subtitles. It seems that interest in “style” has somewhat waned over time and that somehow ‘close-captioning’ is merely additive in nature. With the advent of imaginative credits added in complement to movies, I would like to see ‘styles’ reintroduced to make subtitles and close-captioning more a visual part of the movie, but alas, as you mentioned…the added expense.

mckelly. Thanks for the compliments. Yes, it’s strange to think of those early processes, when we can do almost everything now with software, in a fraction of the time. Re your comments about ‘style’, in some respects some style is returning to titling in general – for instance I think it’s interesting how the visual representation of texting has varied from film to film and in TV series. Closed Captioning has become more of a convenience and, to be honest, I think it lacks style. It’s just too impersonal. Still, it’s early days in terms of modern technology so who knows what the boffins will come up with next.

Brilliant! Especially sometimes when misunderstandings happen due to being lost in translation.

Munjeera, Thanks, it’s always good to hear from you 🙂 Well, mistakes inevitably happen, even with professionals, but some fansubs have to be seen to be believed. One of the worst culprits these days is that damned Google translate. No machine will ever understand the subtleties of human vocal interaction. Cheers

It is very important for a movie to have subtitles so that I can easily understand the story line. For example, sometimes the actor speaks too fast or the actor has weird accent such as British or American accent, I find it quite hard to get what they said, so now subtitles is needed for better understanding.

Frey. Hi and thanks for your input. I’m pleased you recognise the importance of good subtitling. When subbing a fast piece of dialogue, it’s sometimes necessary to trim down what’s being spoken, so that the viewer can understand at least the essence of what’s being spoken, within the time constraint. It’s all down to the number of characters per second that the average viewer can read, that’s why subtitles are restricted, at least professionally, to a maximum of 36 characters per line.

I have to admit that I chuckled at your comment, regarding ‘weird’ British or American accents. You didn’t state whether you meant you found it difficult to understand British and American actors speaking in another language (your own?) or not. In which case, if that’s what you are referring to then those actors should have been better prepared by their dialogue coaches as that’s what they are employed for. It can be frustrating to hear one’s own language mispronounced repeatedly as it obviously means the brain has to process and reprocess the same information. If you are referring to your difficulty in understanding British and American actors speaking English, then please try to find another term to use other than ‘weird’, as that comes across as somewhat prejudicial. English is, after all, the native language to both Britain and America so our ‘accents’ are equally native and natural to us, as natural as Australian and New Zealand accented English is to the inhabitants of those countries. There’s nothing weird in using one’s mother tongue and I would never criticise an Indian for having grown up speaking English with an Indian accent.

Anyway, getting back on-topic. Subtitles are a great help to many and, as you pointed out, aid a better understanding overall. Cheers me ole’ mucker 🙂

We must appreciate the work done by all those film makers in making their movies complete with subtitles.

Garland Blocker. Thanks for your comment. One small point of correction though – it’s not the film makers who decide on the subtitling; that’s done by the production company. The work is then farmed out to an outside agency, such as TitraTVS, or, increasingly so these days, outsourced to the cheapest bidder. I’m sure that if the actual film maker had any say in the overall process then we would see good quality subtitling as a matter of course for all commercially available films. 🙂 However, you’re correct insofar that we must appreciate the work done by the professional subtitler, an invaluable part of the overall process and without who it would be a case of ‘Je ne comprend pas!’. Watch ‘The Invisible Subititler’ for more information on the subject. Cheers.

This is the first article that I read on this site and I’m impressed by the depth of research and writing quality. The pictures were eye-opening and the topic was cleverly chosen. Subtitles are common and usually unappreciated so this article is a reminder that some of the most common items in our society usually have interesting and complex histories.

chloet2. Thank you for your appreciative comments and welcome to The Artifice. Here, you’ll find a wide variety of subjects covered by an equally wide variety of writers, so you can be sure to find something to entertain, educate and inform. Focusing on your comments: the reason I wrote this article was to draw attention to subtitling in general. It’s ironic that the aim of the professional is to be as unobtrusive as possible; to remain ‘invisible’ and yet without them, our world of visual entertainment would be so much the poorer. Thank you once again.

Great article

Thank you.

Very interesting article highlighting the hard work and innovation that has gone into subtitling over the years. Maybe I’m biased as a former language student who has always watched international cinema but it always annoys me when I hear people say “oh I can’t be bothered to watch a movie where I have to rely on subtitles”. The fact that these subtitles (when done well) manage to make films accessible to people across the world is amazing. Furthermore I find it fun to watch a movie in one of my secondary languages and compare to the message conveyed by the English subtitles, especially when they have the challenge of interpreting a joke or cultural reference.

midado. Thanks for your comments. I agree with you completely regarding the reluctance of some to even give subtitled films a chance. There are so many great films they are missing out on. Ah yes, the challenge of interpreting a joke or cultural reference is a very taxing one and although I am a mere amateur, I have to admit there have been times when it’s taken me a good 20 minutes or so to come up with a suitable interpretation for an English language viewer. Still, I actually enjoy the challenge.

i’m always watching foreign movies with subtitles

Glad to hear that! I think it’s a shame how some are put off by subtitles, when there is a plethora of great film making out there in a wide variety of languages.

I honestly never stopped for a moment to think how subtitles and intertitles came to be. I loved reading this article and how much more I know about cinema now. Thank you!

Yvonne T. Thank you for your kind comments and you’re welcome. Watch this space, as they say, for there is a further article to come.

This is a beautifully informative article. One of the quotes that I found more interesting was the one about the laser burning through the film. Definitely a serendipity moment, which seems to be one of the most important factors in the history of subtitles. This connects to what I think is a hard science: determining the best possible design for subtitles. When I watch films I’m always changing the font and style of the subtitles, trying to achieve the perfect balance of pleasant and non-distracting. Some TV channels seem to have gotten it right, but with some kind of secret formula. However, I’ve found that the best subtitle designs are always the ones hard-printed to the specific movies they belong, which doesn’t happen often- normally when a character speaks in signs or a language different from the one being used.

I gotta say, what drove me to reading this article is that, as a Spanish speaker, subtitles were my true connection to films, instead of dubbing. I can’t understand when someone says they think watching foreign films is annoying because of the subtitles, when I’ve been reading them my whole life (well, at least since I was 11 and could read them fast enough).

Pigman 08. Thank you for your response and your glowing praise. Yes, I’m sure those serendipitous moments account for a great deal of scientific advancement. If Robert W. Paul’s film hadn’t jammed and lead to him developing the reverse cranking method, the whole process of adding text to film may have taken a completely different route, or even failed to appear; at least for a few more years. In my opinion, James Blackton was probably the ‘father’ of proto-subtitling, although I cannot prove it, so I think it’s a case of like minded, inspired individuals working on similar projects around the same time. Someone was bound to crack the problem eventually, even if only to exploit the commercial possibilties offered by translation for foreign markets.

Your comment about the best design for subtitles touches on an aspect of the next article I have prepared. I’m not giving away spoilers though 🙂 I do agree with your overall statement though. I generally prefer soft-subtitles because I can then, like you, adapt them to complement the film I’m watching. I could tell you some horror stories about some ‘fan’ subtitles I’ve had to rewrite, but that can wait for now. You mention TV subtitling – well that is actually a very different subject to subtitling for film and the processes, at least in the early days, were very restrictive. There’s no secret formula as such, it really comes down to the difference between a person’s visual perception when viewing a film on a large screen, such as at the cinema, and his/her perception when viewing a TV broadcast. There are other techinical problems to overcome as well, but it would need another article to explain everything.

I note that you’re Spanish. You may well appreciate an article I’ve just rewritten (still tracking down a few, last references to include) about a certain, notorious Spanish cult film from the 1970s. I’ll be uploading that sometime this coming week. I’d be interested in your feedback. Thanks again for your response.

Great article!

I really do appreciate his brief history of subtitled because as someone who is hearing impared, subtitles is how I watch movies.

I can go to theaters some times but most of the time I end up missing some info.

Which is why I love Netflix and Disney plus.

However theaters with close captions are hard to come by

Amelia Arrows. Thank you for your praise. As an amateur subtitler who follows professional guidelines, as opposed to a ‘fan’ subtitler who doesn’t, I’m keen to make my subs as easy to read and understand as possible. There are very few theatres that cater for hearing impaired, which is why I thought Jack Ezra’s system seemed to be the best solution, considering how cheap it is. I live with tinnitus so I am all too aware that one day my hearing will deteriorate and I’ll have to rely on subtitles as well.

A timely article. The South Korean film Parasite by Boon Joon-Ho scored Best International Feature and Best Original Screenplay. Proving that, for non-English language films, subtitling is a sign of more good things to come.

L:Freire. Thank you. Yes ‘Parasite’ deserved the recognition and awards. For once I agree with Hollywood – now that’s something I never thought I’d ever say! Korean cinema is on the rise and now, more than ever, good quality subtitling will be essential for introducing viewers to ‘foreign’ films.

What a better way to highlight the impact of such an overlooked feature as the subtitle than to look back on its history.

The transition from silent film inter-titles to foreign language translations has so much to unpack and reading this really brought fresh insight into that evolution.

On a side note, I’ve always noticed how much is omitted through the filter of subtitling. Whenever a character speaks French, for example, I’m following his/her spoken word while reading the text and it just isn’t the same; you miss a lot of the nuances that add to the character’s … character. I’m sure that’s a downside to any translation of the original, but it’s a shame that those who don’t understand the language are only able to grasp the bare bones.

At least we have an outlet to international cinema.

dbotros. Thank you for your comments. Yes, it’s a fascinating subject and one in which I, as an amateur subtitler, have a vested interest.

Your side note makes a valid point and I do agree with you. However, in defence of subtitlers, both professional and amateur (though not ‘fan’ subtitlers, who appear to do as they please), we work within fairly strict guidelines, so at times it’s simply not possible to relay an accurate translation. Essentially, subtitling is there to aid the storytelling, rather than explore the subtle nuances of speech – but I too have felt frustrated when I’ve had to resort to a lowest common denominator. Anyway, thanks for reading and appreciating the article.

Hello,

I would like to quote this article on a paper. Could you please tell me your full name?

Thank you very much in advance.

Thank you, Fernando. My non de plume is Amyus Crewe. If there’s any further information re subtitling you may wish to know then feel free to send me a private message and I can supply you with a list of resources and copies of pdf files I used in my research.

FYI only registered writers can send PMs.

Oops. I didn’t realise Fernando wasn’t a registered member. Thanks for the FYI.

Fernando. As a follow-up to my previous comment, and further to Misagh’s comment, if you do wish to contact me then you’ll have to do so via the Artifice editors. Sorry, I didn’t realise that you weren’t a registered user.

A good essay, interesting topic to read about.

Especially at a time where foreign films and multi-cultural films are becoming more popular and mainstream here in the US, this is a fascinating history to understand!

This community is one of the best community and I think this community and people are very helpful so I want to ask a question here that I downloaded the designing font style from the Fonts Bee website so now I can not find any way to add the fonts style on PhotoShop if anyone knows about this please tell me about this and proper guide me

Your question is a little off-topic for subtitling, unless you wish to create a font or fonts for a particular subtitling project. Nevertheless, I have done a very quick search for you and there are numerous sites that can help. I don’t use Photoshop, so you may find what you’re looking for via one of these links:

https://www.solopress.com/blog/tutorials/how-to-add-fonts-in-photoshop/

https://www.creativebloq.com/how-to/add-fonts-in-photoshop

https://www.wikihow.com/Add-Fonts-to-Photoshop

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VrH6KvhlNJg

Good luck

Well written