Aesthetics of Tableaux Shots In A Globalising World

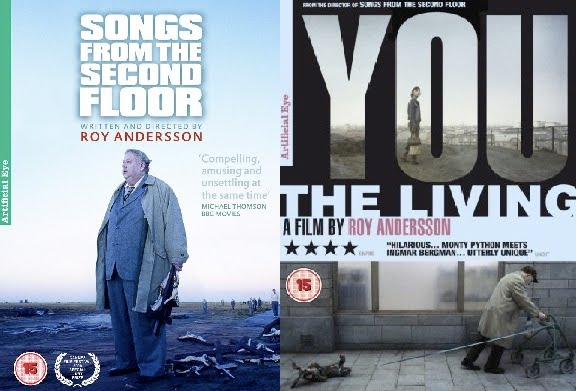

Roy Andersson is an acclaimed Swedish film director well known for his ‘living trilogy’. The film Songs from the Second Floor, as the first film of the living trilogy, is acclaimed for its stylish use of static camera and the accumulating tableaux of choreographed action (Mildren, 147). The bizarre tableaux of shots are idiosyncratic visual representation of the trapped and freezing globalising world, suffused with spectral disquiet and a black comic squeak of hysteria.

As a typical nordic noir film which was made against the globalising trend of neoliberalism, Songs from the Second Floor has its unique aesthetic and political significance in expressing the European identity and the political ideology under the background of globalisation, through the ‘slowness’ of rigorous tableaux of shots. The long take used in this film extends all the sadness and suffering in human life in such a rapidly transforming world, and the rigorous tableaux of shots is the pursuit of the slowness reflects the changes of humanity and morality in a highly-speeded globalising society.

In this film, capitalism has exacted a spiritual price, and the bureaucratic choices are questioned, as every one of the businessman and dignitaries are caught at the end of their life rope. The 46 tableaux of shots do not only act like 46 paintings in the art gallery of post-modern society, but they also connect to each other within the static framing, working together as a whole to show the distorted human life, as well as the humanity’s downfall to economics. So through these interconnected 46 vignettes, the misery of human life is zoomed in to a larger social and political context. This article will discuss some aesthetic and political significances of the rigorous use of tableaux of shots in Andersson’s Songs From The Second Floor, by exploring the aesthetics of doubled effects of tableaux shots and the history of the tableaux in medieval European satirical paintings, in order to draw attention to the implications of viewer and the modern.

Firstly, the tableaux shots and scenes create doubled effects of reality. In Songs from the Second Floor, the tableaux of shots and scenes have double reality effects: as still images and as moving narratives. As still images, the 46 tableaux are like 46 paintings in the exhibition hall, they themselves bear the significance of revealing a series of sad stories of human life. The desperate man gets fired by his boss who he has worked for 30 years for, the soot-covered furniture businessman Kalle goes bankrupted due to his wrong ‘speculation’ in global financial crisis, the 101-year-old general lives the rest of his venerable life in a giant metal crib, the magician accidentally hurts his guest and many other examples, are all depicted vividly within the static framing, offering spectator a viewing experience of melancholy and deep sadness.

Then, as moving narratives, these tableaux of shots and scenes help to push the plot forward and get across the section of different people who live in the same city line. The 46 tableaux shots and scenes are not dealt with in an isolated form but every single of them has the interrelationship with each other, pushing the narrative forward and deepening the satirical effects. For example, the film starts with the begging scene from the man who lost his job, then goes on to illustrate Kalle’s family situation: Kalle himself goes bankrupted and his son goes mad due to the writing poems; later after the sacrificed girl scene and the failure of Jesus merchandise scene, the film reaches to its climax, and to spectator, the satirical feelings become the strongest.

Also, in the silent song scene, the moving narrative is created within the passage of time. The furniture businessman Kalle is standing silently in the middle of the bus in great despair, and all the other ghostly people stand around him wide open their mouth singing in silence, with the background solemn music playing. The playing of background music creates the passage of time and reveals the moving narrative, creating the tension between the desperate man and his outside world, as well as between the stillness and the motion.

Therefore, tableau creates two modes of reality, one belongs to the paintings and the other belongs to cinema. Tableaux shots double the reality effects due to its mixture of stillness and passage of time, and they recreate the temporality of time and space by disturbing the system of stillness and moving action, as tableaux shots offer the possibility for the strategies such as the fixed framing, long takes and slow motions to function in the films. When spectator is invited into these tableaux shots, they are invited into a doubled reality of time and space, one is the painterly static world and the other is the moving world with the passage of time. In this sense, the doubled realty creates doubled aesthetic significance and meaning, both as still paintings and as moving narratives, and the intersections between the cinema and painting reveal the heterogeneous space of cinema (Vidal, 111).

Secondly, the tableaux shots and scenes in Songs from the Second Floor are inspired by traditional European satirical paintings, and they carry a mixed satirical significance of medieval time and modern. Tableau has a long history in European painting and other art industries, and the satire theme and creative style in traditional European paintings inspire Andersson’s strategies in dealing with stinging satirical films. According to Mildren, Andersson’s static aesthetics lie in a cinematic adaptation of a painterly viewing experience which is inspired by Bruegel, and Andersson’s work can be considered as a combination of macabre mediaeval imagination and modernist depictions of the dream psyche (149).

As to the inspiration of the mediaeval painting, Andersson’s visual style has its original expression in Pieter Bruegel’s paintings. Bruegel is a famous European painter at Renaissance and he worked mostly on peasants’ theme painting and depicted a vast panoramic satire, creating new form and experience of paintings with familiar traditions and topics. Through myriad tableaux, Bruegel built up his satire in one space through a sense of madness, and this is captured in Andersson’s film as well. For example, in the horrifying sacrificial lamb scene, spectator got a strong sense of satire coming from both the sense of madness and the medieval style mise-en-scene. In this scene, with the backdrop of millions of indistinguishable people, an innocent little girl Anna is led off a quarry precipice blindfolded due to the sacrificial ritual, and all the solders and clergy are standing their silently and solemnly. This scene can be read as a recreation of the medieval religious ritual, and it is filled with Bruegel’s ‘sense of madness’ and the ‘descent into the hell’ (Mildren, 149).

Moreover, Andersson’s modernist depiction of dream psyche is expressed through the modernist fancy visual effects and the absurdist black-comedy content. The dreamed landscape, Anna’s white dress and the clergy’s black suits, and the exaggerated silent ‘viewer’ who fill out the backdrop, all fancy visual representation depicting a bizarre sense of comedic and madness. The mixed bizarre outfits of mediaeval and modern and the imagined modern ritual sacrifice are both depicted in static framing, drawing our attention to the visual textures of the film as a dream psyche. These modern but medieval-like elements comprise a bizarre spectator sport, executed by a society gone certifiably batty. Therefore, combining medieval satirical paining traditions and modernist depiction of dream psyche, Andersson creates the tableaux shots in a strong sense of ‘mad’ satire. Through the rigorous use of tableaux shots, Andersson draws connection between the medieval and the modern, creating mixed horrifying and comic feelings for spectator, questioning the modern society and modern politics through a combination of the history and modern.

Apart from that, the narration mode which is centred by omniscient spectator is revealed through the tableaux shots and scenes, creating different dimensions of gazes to engage with politics. The implications of viewer are often taken into great account in formal political films as important political elements, and different viewer positions set in different dramatic situations have different effects. Instead of being disposable and merely for commercial recreation, by putting its omniscient spectator into a moral centre, Songs from the Second Floor allows the spectator to stand within the fiction, and watch and think this film without the assistance of the ‘given’ moral by the film itself. Being in within the film and be a participant rather than the mere viewer allow spectator to take watching this film as a social act and an approach to reach to the others as well as the society. When the 46 tableaux shots present in front of the spectator, they are invited to a fictional world where they are participants of events rather than the outsiders or escapists, and the passage of time that long take creates within the frame makes the spectator lost in this fictionalised world which is a mirror to the reality.

To Andersson, fiction has specific ways to recreate reality, and he believes that it is the reality that fiction establishes rather than the fiction itself. By placing spectator in the narration centre, he effectively creates an imagined reality through different dimensions of gaze, and when spectator enters these tableaux they encounter a myriad of other gazes. The static framing that tableaux and geometrical grids create lock the spectatorial gazes into a specific dramatic space , but the openness which comes from the static long take holding at the same time allows them to look into and out of framing as well.

In these 46 tableaux shots, the gazes can be explored through a few different levels: the gaze from the characters in the film looking at the other characters in the same space, such as in the opening scene there are four more people peering out of the door at the fired man, the gaze looking out of the frame directly at the spectator, and also the spectatorial gaze frees itself to wander into the tableaux. Tableaux and long take slow down the motion and allow spectator to take time to wander around in a free space and think about the events they are engaging. Tableaux create the constantly roving eye directly both by director and viewer, from the still painterly images and slow-moving narratives, creating a solemn yet profoundly comic atmosphere dependent on the control of the viewer’s gaze (Mildren, 148). In this sense, by standing the moral centre, spectators are able to read the film within a social context and they are invited to judge the moral and social tensions by themselves.

Last but not least, tableaux shots allow political poetics to travel through transnational space, expressing the transforming time and society in an accelerated post-modern society. In Songs from the Second Floor, the poetics come from its idiosyncratic visual representation of the movement and the framing, and the political is explored through the question of self-other relations in an accelerated globalising society (Smith, 6). According to Agamben, the western experience of time is split between the eternity and continuous linear time, and the dividing point is history (114). Tableaux used in this film are an idiosyncratic visual representation and combination of the history and modern: in many scenes the grand setting of the backdrop and the wide-angle shooting leads to an eternity and the continuous linear time is experienced through the slow motion and static framing; the ritual and ceremonial repertoire and content in a way depict the history as a dividing point showing a sense of temporality of accelerated modern society. In 21st century, the finance capitalism gradually takes over the traditional capitalism system, under which circumstances the society is accelerated with the fast-speeded production and consumption, and the pursuit of the maximum of the profit is becoming predominated. In this sense, the notion of slowness coming from the static framing and slow motion is a political and aesthetic strategy fighting against the neoliberalism.

In a fast speed post-modern society driven by network, people’s relationship with time and space is twisted and revolutionised, as the digital time makes everything highly flexible and breaks the fixed time space relationship by dissolving them into virtual time and space network (Hassan, 2005). With the backdrop of such fast-speeded globalising society, time and space is interrupted and deconstructed by the speed and there is only present that exists. Under such circumstances, Andersson’s notion of slowness is like a political utopia in a globalising market; the visual representation of Cesar Vallejo’s poems and the long take, the failure of the Jesus merchandise, and father-son conflict in dream and reality, all represent Andersson’s utopian political ideology which assist the slowness travels through the national space and speaks in a global voice.

On the other hand, the political poetics is experienced through the deep sadness of each character’s fate and life. In the accelerated neoliberalism society, our capacity of gaining certainly about future is aging and shrinking (Scheuerman, 12), and the discontinuity of the present and the previous experience is shaking people’s sense of safety. This is reflected throughout almost all the tableaux shots: the man gets fired after 30 years’ working, Kalle’s consistent pursuit of money, and the young girl’s cheating and many more, all depicting a melancholy and sad neoliberalism society full of lies and abandonment and loneliness and uncertain about future.

Tableaux shots as a symbolised and iconic filming strategy of Andersson, carry satirical political significance through its poetic aesthetics. By exploring the aesthetics of the doubled effects of reality and its relation of history and modern, this essay tries to explore the implications of viewer and the political sense in a globalising social context. Since the political poetics is explored through the notion of slowness, the tableaux shots bear both aesthetic and political significances. As a great example of film who is made out of a globalising social context, Andersson’s idiosyncratic visual representation combines history and modern, speaking in an international voce about the disrupted traditional space and time system and the distorted social and human values. As what Mette said in his book, it is more important to explore the effects that ‘transnational’ achieve and the certain concepts ‘transnational’ deal with than simply give stimulative definition of the ‘transnational’ (15). So in this sense, Andersson’s tableaux shots are significant and meaningful as they deal with specific problems in neoliberalism society, and they actively invite spectator into a moral center to think and rethink the value of humanity and society.

Works Cited

Agamben, Giorgio. “Time and History : Critique of the Instant and Continuum.” Infancy and History: On the Destruction of Experience. Trans. Liz Heron London: Verso, 1993. 97-116. Web.

Hassan, Robert. “The Second Empire of Speed: Networked Society.” Empires of Speed: Time and Acceleration of Politics and Society. Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2009. 67 – 96. Web.

Mildren, Christopher. “Spectator Strategies, Satire and European Identity in the Cinema of Roy Andersson Via the Paintings of Pieter Bruegel the Elder.” Studies in European Cinema 10.2 (2013): 147-55. Web.

Scheurman, William E. “Social Acceleration.” Liberal democracy and the social acceleration of Time. Baltimor, London: The Johns Hopkins UP, 2004. 1 – 25. Web.

Smith, Richard. “Week 12 Lecture: Tablea in Songs from the Second Floor.” University of Sydney. Carslaw lecture theatre 373. 17th May, 2016. Word Doc Address.

Vidal, Belén. Time and the Image: the Tableau. Figuring the Past: Period Film and the Mannerist Aesthetic. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012. 111-62. Web.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The tableau here seems to have a similar effect to the montage of Russian cinematography of the 1920s.

For me – I´m a Swede – Roy Andersson incarnates the worst side of most Swedes approach on life. Let me first say – I actually like him a lot as a commercial director. But when he speaks out of himself, without the cynical, earth connection that the commercials bring, I find him arrogant and pretentious, as most Swedes when it comes to having an on opinion on Life. Most of them ceased to be christians, but on the same time got rid of their spiritual language, and never developed a new one. They cut off their concious connection with the great mystery, and then surprise themself with living in hell, where everything lacks deeper meaning – and are arrogant enough to complain about it! They relate God to christianity, and are etno-centric enough not to take in that their are other approaches on spirituality and that atheism is not the only option. I think it´s a cowardly approach; if you don´t even try to get down on your knees asking for mercy, asking for good things, who are you to say anything about life lacking meaning? (Now, to defend my fellow Swedes, listen to Swedish music… and all of a sudden you find lots of spiritual expressions… In that area they give themselves permission, using it as an oasis in their spiritual desert.)

I feel like the influence of filmmaker Jacques Tati is apparent in Anderssons work, and i doubt it is an unconscious influence.

I am actually writing my history of art dissertation on Roy Andersson at the moment and came to The Artifice to procrastinate! So happy I stumbled upon this. I really like it. Very fresh take from the articles I have read which seem to take them much more on surface level. I’m trying to make the argument that Roy Andersson’s films are history pantings of the 21st century, basically he is 2010s version of Peter Brugel.

I’ve never heard of this director but I now I want to watch his movies.

Love this wholeheartedly. Yes it’s bleak and dark, but his work is amazing.

Even if I didn’t know about the director, I’d go to watch his films just for the titles alone.

Would Roy Andersson or Andersson’s style be the best way to approach a film about Brexit? I watched a hilarious Boulting brothers film the other day called Carlton-Browne of the F.O. and thought they Brexit would have been their dream project. Perhaps. But it would demand a twist of Roy Andersson too, probably.

The greatest living film maker.

That’s an overstatement.

A credit to his nation. Smashing fellow.

The characters in You, the living and Songs from the second floor have a stark and grotesque quality reminiscent of the Berliners depicted by Dix and Grosz. Unlike the two painters, Andersson has sympathy for his subjects.

Nobody takes any notice, but I recommend Andersson’s films to anyone who will listen. Songs From The Second Floor is a masterpiece.

I take notice. I got into his films by word of mouth from people like your good self. Andersson’s stuff is hilarious.

I remember taking a punt on the film when it first came out and was so glad I did.

The end sequence in the scrap yard is one of the finest end sequences in any film.

This one scene about the psychiatrist is also rather awful to watch in a low-key kind of way

Tableaux Shots. Okay finally I understand what this word means.

His first film, A Swedish love story, is worth watching. The title isn’t ironic: it’s a moving story of the awkward love between two teenagers, not a surreal comedy like his two most recent films.

Magnificent film maker!

Any film maker that gives a quote from Peruvian Poet Cesar Vallejo at the start of a film is a man of some standing in my eyes!!! A real original!!!

Such a shame Ron no longer does commentaries; tell you what, him and Clive were a great double act.

I love this man. His work has echoes of other things but there’s nothing truly like Roy Andersson. He makes even someone wholly admirable like Wes Anderson seem lacking by comparison. That good.

Haven’t seen anything from this writer/director before. So, I guess I’ll start.

As much as I love him, there is a tiny part of me that is disappointed that he hasn’t changed the formula one bit from Songs of the Second Floor.

Maybe it will change when he releases his next film in 2035.

I love Roy Andersson’s stuff but totally understand why people don’t get it.

Like a bad Kaurismaki film with better plastering and less wry humour.

Then that’ll be good!

Just watched two of his movies. Very uncanny. I felt that of multiple themes, the overarching message was of the irony in entertainment.

Roy Andersson is a beautiful director, was first introduced to his work when watching You the living.

Andersson’s characters are so afflicted and silly but also dignified. Glad to read your perspective.

I know what I’ll be obsessing over this weekend.

Roy Andersson for the mother-effing win. Always.

I haven’t seen You, the Living, but Songs from the Second Floor was quite wonderful.

An interesting read and thank you for introducing me to a director I’d heard about, but up until now haven’t watched anything he’d made. ‘Songs from the Second Floor’ sounds like a good place to begin.

An incredible article!

In a world inundated with pointless trilogies, designed solely for the purpose of churning money from a single good product, your article has enticed me enough that I will add these movies to my watchlist. It is very pleasing to be introduced to the works of creative legends.

An interesting essay. Noticing that it is a film from Sweden, one would think, at first, that this was a skeptical view of American capitalism.