Tarkovsky’s ‘Stalker’: Deep as a Mirror

Seemingly more often than any other of his seven feature films, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979) is chosen as a filmic accompaniment to artistic exhibitions. So often has this been the case at my local cinema-gallery that when experimental filmmaker Hiraki Sawa requested to screen the film during the run of his exhibition of Lenticular, he was asked to choose another of Tarkovsky’s films instead.

The second of two science fiction films which bookend his loosely autiobiographical Mirror (1975), Tarkovsky’s Stalker is often discussed in terms of how ‘deep’ it is, how rich with existential meaning. But the director is notorious for insisting that his films hold no coded messages, that his art is a visual poetry which strives to convey emotion rather than meaning:

If it is to last, art has to draw deep on its own essence; only in this way will it fulfil that unique potential for affecting people which is surely its determining virtue and which has nothing to do with propaganda, journalism, philosophy or any other branch of knowledge or social organization. (Sculpting in Time, 184)

Somewhat problematically however, Stalker, like Solaris (1972) before it, is based on a seminal science fiction novel. Where Solaris retained its title and is thus easily identifiable as an adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s 1961 novel, Stalker is a pared down adaptation of Boris and Arkady Strugatsky’s Roadside Picnic (1971). Strangely enough for a sci-fi film, Stalker contains virtually no visual elements which are indicative of a parallel world, future time, or alien presence; the only real suggestion that there may be a dystopian society within the film is the security which surrounds the Zone.

Traditionally, sci-fi novels, especially Russian ones, were critiques of society; totalitarian governments, dystopias, lack of free will, and critiques of capitalism could all be wrapped up in fantastical elements to bypass censors. So why, one might ask, if his aim was to divorce art from ‘knowledge of social organization’, did Tarkovsky choose the science fiction genre for two of his films?

The answer, it would seem, lies in the personal journeys made by the protagonists of the source texts. As Tarkovsky explained when Naum Abramov posed this question to him as part of an interview about Solaris in 1970:

I’m interested in a hero that goes on to the end despite everything. Because only such a person can claim victory. The dramatic form of my film is a token of my desire to express the struggle and the greatness of the human spirit. I think you can easily connect this concept with my earlier films. Both Ivan and Andrei do everything against their own safety. The first physically, the second in a spiritual sense. Both of them in a search for an ideal, moral way of living. (Interviews, 33)

Indeed, the director’s focus in Solaris is not on the technological aspects of the setting, but on the isolation and nostalgia felt by Andrei in his separation from his home. The institutions of science and religion are compared, merged even in the sentient entity that occupies the planet’s surface.

Similarly, there is a myth in Roadside Picnic, of a ‘golden sphere’ deep in the Zone which grants wishes to those who can reach it. Only certain wishes, however, are granted – subconscious desires, rather than requests, and the results are rarely those which were sought . This is what Tarkovsky translates into the Room. He focuses on this almost religious component of the Stalker’s story, sidelining the mercenary aspect of the protagonist’s – Red’s – nature in favour an exploration of faith.

The trio’s journey is both a pilgrimage of faith and a search for knowledge; in the novel, the object of Red’s quest was to reach the Golden Sphere, a large golden orb (a sun icon, an apple of Eden) which grants the innermost desire of those who stand before it. Tarkovsky cut this overt symbol along with the majority of the other sci-fi elements of the source text, paring down the fantastical in order to leave a ‘minimum of external effects’:

The ‘ascetic’ plot of Stalker was a central part of a conscious strategy to focus attention almost wholly on the image itself and avoid ‘entertaining or surprising the spectator’. (Elements of Cinema, 152)

By stripping down the original story in this fashion, Tarkovsky lays emphasis on time, space, and emotion rather than the alien aspects of the Stalker’s world. The quest for the ‘apple of knowledge’ becomes a quest of self discovery and the Other shifts from a physical presence, overtly extraterrestrial, to an unseen presence, an atmosphere rather than a scattering of artefacts.

As with Solaris, Tarkovsky translates the extraterrestrial Other into the Divine Other, a simple enough transformation as both are considered beyond human comprehension. Whereas the novel identifies the Zone as overtly alien, littered with the evidence of visitation, the film shows only terrestrial nature and human relics; the debris discarded by the visitors in the Strugatsky’s novel becomes the leavings of humanity. Where the characters of the novel conjecture over the use of a number of alien devices discovered in the Zone, those of the film find only human objects reclaimed by nature, the Divine Other.

The idea of nature as a representation of the Divine is one central to English Romanticism, and its presence in Stalker is further identifiable in the linking of the Edenic Zone with miracles; nature becomes both a physical manifestation of the Divine will and a mirror of the human soul, a conduit between man and God. The internal bleeds into the external as artistic spirit reaches out to the Divine. Indeed, where Stalker initially chooses Professor to lead their expedition, Writer is given lead position when the Zone spares him after wandering from the path. As an artist, he is arguably the most spiritual of the three; Stalker is a devout apostle, his faith being the strongest, but it is Writer who shares in the creative powers of the Divine.

This Romantic sensibility is further echoed in the party’s departure from the town where the film begins; Wordsworth and his contemporaries, attributing the countryside and Nature to the Divine and creativity, advocated a departure from the oppressiveness of city life during the Enlightenment. As Stalker tells his wife, ‘everywhere is a prison for me’, but the Zone is virtually free of human influence, aside from that which the Stalkers, its faithful servants, invite in. There, Stalker feels alive and free, and at his most spiritual; the evidence of human life within its bounds – rusted tanks, collapsing telephone pylons, a decaying house – is all being slowly absorbed by the terrain.

The house around which the three pilgrims circle is the location of the mysterious Room, and thus takes on the role of the Romantic ruin, the home becoming a shrine. The locus of the Stalker’s faith is thus rooted in nature, home, and the past the divine becoming humanised, anchored to the earth and the Stalker. It can only be approached by navigating the perils of the feral Zone, a pilgrimage into a memorial garden. Indeed, Stalker’s remark upon entering the Zone, ‘home at last’, and his consternation upon returning to his family home, embody the term ‘nostalgia’, ‘the pain of the return home’ so central to Tarkovsky’s films.

The Zone can be seen as an Eden, and is thus representative of the original home of humanity. If, then, as Tarkovsky claims:

The Zone doesn’t symbolise anything, any more than anything else does in my films: the zone is a zone, it’s life, and as he makes his way across it a man may break down or he may come through. (Sculpting in Time, 200)

Then Stalker’s journey through it is representative of his struggle to maintain faith in the face of life, the building of human relationships and the discovery of the self. The reality of the Zone is questionable, all the more so for Tarkovsky’s transitions between monochrome and colour. The initial switch takes place during the trolley journey into the Zone, cutting from the close ups of the pilgrims on their trolley ride of indeterminate duration to the resplendent greenery of the Zone. But what is the significance of this change? Did Tarkovsky withhold colour for the same reasons that he did with Andrei Rublev (1971)? To increase the impact of that sudden burst of colour?

In their 1946 film A Matter of Life and Death, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger used colour to differentiate between the two realities of the narrative, and it is possible to apply a similar logic to Stalker; the urban areas, the Stalker’s home and the military perimeter are shot in a rich sepia monochrome (achieved by filming in colour, but printing in monochrome), and sequences in the Zone or which involve its Otherness are in colour. Perhaps, then, it might be posited that the crossing of the border into the Zone signifies a transition from external reality to an internal, subjective one.

Indeed, this argument can be supported by the scene in which the three men rest next to the river, when Stalker slips into a monochromatic sleep, shifting from the coloured external world to a monochromatic dream one. His dream, however, appears to take place within the Zone, without colour. The assignation of a colour scheme with a specific geography or reality thus becomes problematic, unaided by the director’s insistence that the Zone is simple an allegorical platform for man’s journey through life. But, if the film’s element of Romanticism is considered, the vibrancy of the Zone, like that of the icons revealed in the final minutes of Rublev, can be seen as an indication of the Zone’s Divinity as it is perceived by Stalker.

Rublev’s icons were the only instances of colour in the film, serving to create a sharp contrast between the way he saw his world and the bleak way in which Tarkovsky represented it to his audience, and the Zone can be seen in a similar manner. The spirituality of the film is all rooted in the Zone, of which the Stalker is a disciple and extension. This theory might explain why the Stalker’s dream is in monochrome – because in sleep he is detached from the Zone – and the end sequence with his daughter Monkey is in colour.

Born with abnormalities caused by her father’s trips into the Zone, Monkey appears to have telekinetic powers; the colour of this sequence then is due to her ties to the Zone, an argument supported by Tarkovsky’s assertion that:

From a symbolic point of view, [the little girl’s powers] represent new perspectives, new spiritual powers that are as yet unknown to us, as well as new physical forces. Furthermore, they could represent something else. People have always looked forward to the end of time as we know it, probably because their lives didn’t satisfy them. Despite this, life goes on. It’s true that today we have a nuclear bomb and this contributes to the apocalyptic dimension. (Interviews, 59)

The important point to be taken from the director’s views on this final scene is that the girl’s powers are both ‘spiritual’ and ‘physical’, a blending of science and spiritualism within a single, arguably natural organism. Again, the miraculous, the fantastical, is linked with the natural, a theme which Tarkovsky’s penchant for depicting the natural elements only serves to strengthen.

Earth, wind and fire are all given ample screentime in Stalker, but it is water which seems to have the greatest presence. It acts as a dampener, a neutralising force within the film; Stalker drops Writer’s gun into the water where it becomes just another artefact of humanity, harmlessly catalogued and deprived of its function, like the other objects seen in the river sequence: a slow tracking shot reveals coins, a painted icon, a gun, to name but a few. Similarly, Professor throws the components of his bomb into the water on the threshold of the Room, rendering it harmless, just as the bullets fired at him as he wades toward the trolley at the beginning of their endeavour drop harmlessly into the water.

Water, too, permeates the climactic scene of the trio’s trip in the Zone; Writer and Stalker’s quarrel sees them splashing around in the pool outside the Room, the same pool into which Professor throws his dismantled bomb. The faith that Writer and Professor held for the Room was derived largely from Stalker’s own, and when confronted with the truth about Porcupine’s suicide and the nature of the wishes granted by the Room, Stalker reaches a breaking point. His charges, seeing their guide’s faith waver, decide they would rather not complete their expedition, rather not discover their own innermost desires, fearing what it may reveal about their true natures, and as the three men sit dejectedly before the Room, the goal that they sought, it begins to rain. Again, water acts as a neutralising force, in this instance dampening the men’s tempers and washing away the ruins of their original intentions.

Bodies of water within the film might also be seen to represent the mind; if we consider the Zone to be a non-literal, psychical journey, the artefact laden river can be read, literally, as a stream of consciousness. This shot, in monochrome – and so Stalker’s subjective/subconscious viewpoint – tracks up the river bed, showing the numerous objects abandoned there. If the river is considered as symbolic of the subconscious, the objects on its bed become elements of culture and human life, embodiments of values and information gained from a specific cultural background.

Alternatively, the stream might be compared to the river Lethe of the Greek underworld, the waters of which had the power of forgetfulness. The items in the river are discarded, forgotten, and perhaps by dropping the gun and the bomb into the water, Stalker and Professor are not just relinquishing them but forgetting the intentions attached to them, the intentions of violence towards the Zone. The image of the stone being dropped into a well is linked to Writer’s speech in the cathedral like sand-room, the rock disturbing the still water perhaps representing the way in which his journey into the Zone has shaken his beliefs, the very core of his being.

The dropping of the stone, like Stalker’s upending of Writer’s liquor, and the various incidences of objects being dropped into water, are also suggestive of a sort of tributary system. It is as though these items the visitors give up are offerings to placate the intelligence of the Zone and buy them safe passage; it is after Stalker pours out Writer’s drink that the latter apparently narrowly avoids danger due to a mysterious warning. Likewise, Stalker’s dropping of the gun into the waters of the tunnel seems to be connected to Writer’s survival in the sand-room, or the ‘meat-grinder’.

This shedding of possessions is reminiscent of what Joseph Campbell terms ‘the passage through the gates of metamorphosis’ (The Hero With a Thousand Faces, 87), using the Sumerian myth of the Goddess Inanna’s passage into the underworld as an example: she must pass through seven gates to reach her destination – an audience with her sister, Queen of the underworld – and remove an article of clothing at each gate, ultimately leaving her naked and defenceless before her twin, the mirror aspect of herself. Similarly, it is once the three men have reached the threshold of the room, paying passage and navigating danger, that they must, in the film’s climax, face themselves: dare Writer and Professor enter the room and discover their true natures in the attainment of their innermost desire? It seems not.

The trio’s pilgrimage has not been in vain, however; although they do not enter the Room and discover the truth of its ability to grant wishes, indeed the truth about themselves, their very reluctance to enter shows that they maintain faith in the reality of the Zone’s miracles. As Robert Bird writes:

It seems that the reward for their travails has been the very acquisition of faith in the act of overcoming material resistance. (Elements of Cinema, 150)

The ending of the film does not offer much in the way of clues as to whether or not the trip to the Zone was a success, whether the Room and its powers are real or whether the tale is all just a myth maintained by Stalker’s personal beliefs. It appears that the men did not enter the room, and yet the journey has left them all changed: Writer realises that it is not the commercial aspect of his work that is important, not critical acclaim, but artistic merit, the soul and message behind his writing, a sentiment echoing the director’s own. Professor came to realise that he could not, did not have the right, to destroy the Room just because he fears and does not understand its power, and Stalker seems to come to the realisation that his ‘miracles’ do not really help people, that it is not the destination which affected his clients, but the journey.

Indeed, Tarkovsky himself argued that:

‘The existence in the Zone of a room where dreams come true serves solely as a pretext to revealing the personalities of the three protagonists’. (Interviews, 50)

His interest, certainly, appears to be in using external spaces to examine his characters, to reveal and confront their flaws in order to bring them closer together and illustrate his belief that:

In Stalker [he] made some sort of complete statement: namely that human love alone is – miraculously – proof against the blunt assertion that there is no hope for the world. (Sculpting in Time, 199)

This would seem to be the essence of the speech made by Stalker’s wife in the penultimate scene of the film as she tells us how she stuck by her love of Stalker against the advice of her mother, knowing the trouble it would cause her. But despite any misgivings or hardships, their marriage yielded Monkey who, although apparently a mutant of the Zone, is presented as a positive result, an embodiment of new spirituality and hope.

These readings, however, are just that: readings, inferences influenced by the opinions of an individual perspective. With Stalker, Tarkovsky sought to create a visual, temporal poetry which connected with his audience on an emotional level; entertainment and meaning were sidelined, if not dispensed with entirely, and likely it is the film’s obliqueness that invites so many who see it to consider it deep or profound. Such images as Writer’s crown of thorns naturally suggest that there is some Biblical metaphor at work, but despite adopting (and indeed adapting) a genre so often used as a cipher, Tarkovsky does not appear to have attached any meaningful message to Stalker beyond that of the importance of faith and love.

The film is, it would seem, exactly what you make of it.

Works Cited

Andrei Tarkovsky: Interviews, ed. by John Gianvito (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2006).

Bird, Robert, Andrei Tarkovsky: Elements of Cinema (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2010).

Campbell, Joseph, The Hero With a Thousand Faces (California: New World Library, 2008).

Tarkovsky, Andrei, Sculpting in Time: The Great Russian Filmmaker Discusses His Art, trans. by Kitty Hunter-Blair (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987).

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Great article. Stalker has stunning long shots that I never forget. Tarkovski has a very precise notion of time in cinema. For him, time is the essence of cinema, the most important tool of the filmmaker.

Thank you. I agree, the long shots are nice, you can really feel the time on the screen. I remember reading that Tarkovsky wanted Stalker to feel like one continuous take, almost like it was unfolding in real time. It’s something that Theo Angelopolous and Bela Tarr do wonderfully, too.

This movie was one of the most impressive cinema experiences i’ve ever had.

After seeing the movie I was like ” what the hell was that?”

Well, last time I watched the movie, my english wasn’t so good(russian orig. with english subs and I’m german)so I more or less felt the story. I was really amazed by the long shots and the dullness because it reminded me of my east german home town, where we have places like that,now deserted former occupation zones of the russians and post reunion desolation,places we used to play in as kids all the time. It really spoke to me because I could relate to the pictures.

It works more like a David Lynch film. It evades common symbolism and is

open to interpretation but it isn’t random or pointless. It works more

connotation wise than strictly intellectual.

I agree that it avoids any one, easy interpretation. As I said in the article, Tarkovsky was more interested in an emotional experience than an intellectual one, and given that you found it easy to relate to the images, I guess he succeeded. I like the idea of ‘feeling the story’, I’d have liked, in retrospect, to see the film for the first time without the subtitles.

This particular movie may be one of the cheapest, yet deepest movies ever made. As all Tarkovsky movies it is excruciatingly slow to the point of boredom. That is somewhat intended though. The director addressed this when asked about his style: “It was to weed out the movie goer in the start of the film, the dimwits who were there for shallow entertainment”. Whether I agree with this or not I do see his point. I am a little bit more hopeful for mankind than that, I do believe everyone seek higher truths and meaning. In any case, I think entertainment should engage everyone. And then impart deep philosophical questions upon the viewer. We all thirst for knowledge in some form or the other, we all question our life and its meaning. It must have been torture for Tarkovsky when people threw their interpretations of it in his face, those he thought whom he had weeded out were still left sitting and making their wildly absurd and shallow interpretations. In particular the political ones about communism and/or the west. Thank you for the writeup.

And thank you for the comment. You’re right, Tarkovsky wasn’t particularly interested in entertaining his audience; he compared ‘mass appeal films’ to ‘bottles of Coca-Cola’ due to its lack of emotional depth.

I suppose considering this film deep depends on what we mean by the word. You can call it deep in that, as Lukas said above, you can feel the film rather than understand it, but in terms of meaning I really don’t feel that there’s much there that doesn’t make itself evident. It is, as you say, about life and belief, and any specific readings, such as those about communism and the west, are and can be projected onto it exactly because it’s so vague or open.

This is what I took from the film, and it is most definitely a film and not a movie – a movie is something by which you can actually eat popcorn to while being assaulted with some form of coherent storyline.

I felt as though:

1. This is in my opinion an allegory for life, religion and God. A bit too much? Let me explain. We had the Stalker – a believer. A man with complete faith in all that he does without any attempt at personal gain. The Professor – The symbol of science and the need for explanation of all things. The Writer – The symbol of Art. The intrinsic voice within us all that asks the questions to the big things in life.

2. Russian Literature and its corresponding historical influence. Russian literature has a habit of doing this. The Cherry Orchard, for example, was a tale of Old Russia meeting New Russia and the inability to let go of the old regimes and traditions. Stalker, for me, had a very similar theme. The shift from B&W to colour and back again. A very apparent fear of a new world and everything that comes from the shift to the present.

3. The bomb – and more specifically the dismantling of the bomb. Perhaps a symbolic gesture of Russia’s disarming of itself during the Cold War. We are left with three hopeless wrecks, none any better off than they were before, and one new hope – a child with terrifying kinetic powers – again another symbol of fear of the future and what this may hold for its present denizens.

There are hundreds of themes and no small amount of symbolism throughout the film, the crown of thorns, the large black dog, the child without working legs, the huge industrial landscape, the militarisation, the water, the dust. I cannot begin to try to explain them all, nor can I hope to understand them either, but I do think that any amount of reference can be taken from every individual scene, and it does very much stick in your mind for quite some time.

This movie as an allegory for ART, SCIENCE and RELIGION in search of the meaning of LIFE is also my favourite interpretation of this movie.

I read “Roadside Picnic,” of which this film is heavily based on. I thought the story was incredible and expected such a well-received movie to be similarly amazing. However, I was vastly disappointed. The film is essentially a highly simplified version of the short story.

That’s your misconception. “Stalker” is based on it, only very, very loosely, to the point where the Strugatsky brothers said, about the script, that it was no longer theirs and entirely Tarkovsky’s. You think it’s “a highly simplified version of the short story”, but what you don’t understand is that it doesn’t have much to do with it and gained a life of its own (as you might know, the first part of “Stalker” had to be completely re-shot, the script supposedly changed greatly from the first version to the second – knowing the short story allows you to appreciate some of the “fragments” from the story that aren’t explained in the film, but you don’t need to know it at all to enjoy “Stalker”, I sure didn’t when I first saw it… maybe I would’ve been puzzled at the disparity between the two, like you were).

I have only watched the movie once and was somewhat struggling with keeping in synch with subtitles and the audio since I’m not at all into russian. Will not watch it again.

I know I got a lot more from subsequent viewings, although I liked Stalker from the start, but to understand the message of the film, you need to pay close attention to the dialogs and to some of the symbols used on certain scenes. After a while, it all comes together and you have (at least) a decent idea of what the point is. But, well, if you still don’t like it, you may never like it. Or change your mind later on. I’m not sure if we shouldn’t understand it clearly from the first viewing though. Maybe I’m just not clever enough and Tarkovsky was one of those Russian geniuses, but that’s certainly an irony, that he wanted to communicate ideas to everyone and not for the elites (as he was frequently accused of), and yet, I don’t think the average person can fully understand his works from a single viewing. If these were being judged on the efficacy of the communication, Mr. Tarkovsky would probably get a poor grade… Maybe we just expect communication to be immediate, advertising has spoiled us! (But with me, Stalker had a big initial impact, then I watched it again and again to understand it a little bit better.)

You should give it another try. A less literal approach to this film is generally a good advice. Much of its magic comes from us wondering, not from understanding everything in its entirety.

Lovely read. Subscribed to your RSS.

I enjoyed the movie primarily for the crazy feat of making it one of the most nail-bitingly tension-filled film I’ve ever watched. It’s the one emotion you feel throughout, in addition to wonder. The anticipation of something very very bad to happen, yet it never comes.

I think the fact that we never see the zone really do anything “supernatural” was intentional on Tarkovsky’s part. After watching the film, there is this lingering question… does the zone really have these mystical powers, or are all of stories we hear about the Zone’s powers just an artifact of tall-tales or of the Stalker’s mental fictions?

There are some hints that something weird is going on at the Zone, e.g., the crow twice flying in that sand-dune like room; the phone call ringing when they get next to the room. But it’s hard to know if these scenes represent real mystical aspects of the zone, or if they are just surreal plot devices intended to upend the viewer’s sense of normality.

If you view the Stalker as a child-like character, similar to a classical holy fool, then his treatment of the Zone is very much like how a child would pretend that some place has magical powers and that there are all of these rules that guide one’s actions so as not to upset this magical being. As viewers, we never really know for certain if the Stalker is just pretending (maybe consciously or subconsciously), or if these things are real. So, is the Stalker’s aversion (as well as the Writer’s and Scientist’s aversions) to entering the room due to a fear that his wish might come true, or is it due to a fear that if he goes into the room and nothing happens, then he would have to face the reality of the situation: there is nothing special about the Zone.

To get a bit symbolical here… if we view this film as a commentary on faith and religion, than we can see the Zone as analogous to a religion with the Stalker as the holy fool with blind faith. In real life, for people that adhere to a religion, there is never any direct evidence that their religious beliefs are true (other than via mental experiences, i.e., maybe what the Writer possibly experienced in the sand-dune room with the crow). Yet people choose to believe because it makes their lives more complete. But would most religious people, if they had the chance, really want to know if God does or does not exist? Would they want to risk facing the absolute truth that maybe there is no God?

So the question is: does the Stalker worship the Zone’s mystical qualities because he knows they’re real, or because he wishes they were real? Conversely, the Writer and the Stalker enter the Zone because they want to believe (but don’t yet) because their lives have otherwise become empty in the face of non-belief. When all three of them get to the room they know that entering this room will answer the question once and for all: is the Zone real (i.e., does God really exist). In the end, it seems, Tarkovsky is wrestling with this question: is faith more comforting than actual knowledge of the truth? Would you really want to know the truth if you could?

So, to make a long story short. Tarkovsky diverges significantly from Roadside Picnic because he has changed the point of the story and made it a question of faith vs. knowledge. To unequivocally show that the Zone has mystical powers would undermine this theme.

Actually, Tarkovsky did unequivocally show the supernatural/alien power or anomalies of the zone– it’s the precise nature of the power or anomalies that remains obscure because no one in the movie or the novel managed to understand it… though “symbolists” like yourself might insist on interpreting them as coincidences or delusions suffered by the characters.

What Tarkovsky did was “expand” the last part of the novel, involving a trip to the meat grinder, into a full movie– after the film stock covering the earlier/other parts of the movie were destroyed… And since there is no longer any “context” for the trip to the meat grinder, Tarkovsky could develop his own focus by writing a story which “parallels” the one in the novel.

The interviews on DVD’s special features pointed out that the 2 shoots for the destroyed film and the released film covered completely different material as Tarkovsky didn’t want to repeat himself– so he may have been dissatisfied with the destroyed film in the first place, since it supposedly followed the Strugatsky brother’s script more conventionally…

But in the end, both the movie and the novel engages the “faith vs knowledge” theme because an incomprehensible “Zone” and a reputed “wish granter” present the same questions to all human beings– what do YOU want with/from it, if anything at all? All you know is that somebody said somebody had his life changed/wish granted… you don’t know how or why that would work for YOU.

In the novel, because of the difference in the preceding set-up, the characters and their personal issues are much clearer and obviously different from the ones in the movie. The movie seems to be taking place decades after the events in the novel… when the Zone is all but abandoned and last person who had his life changed/wish granted is all but forgotten.

Don’t assume that the movie is “deeper” or more mystical/spiritual than the novel– just because they explore or emphasize differents questions regarding human existence–as the ending of the novel is even more ambiguous/open-ended than the one in the movie.

“Actually, Tarkovsky did unequivocally show the supernatural/alien power or anomalies of the zone”

I disagree here, though I think this film can obviously be interpreted different ways so I don’t intend to say that I am right and you are wrong.

The final scene sums up my interpretation: we see the glasses moving across the table, and while it looks as though they are being telepathically moved by his daughter, the rumble of the train adds a slight bit of doubt to this assertion.

This scene serves as a microcosm for how I approach the whole film. While we are 95% sure the Zone has mystical powers, there is still that lingering doubt. I personally think this doubt was intentionally left behind by Tarkovsky. There are many more obvious ways of directly showing the powers of the Zone, yet all of the ones we see are vague (getting lost/accidentally backtracking), rely on here-say (e.g. the meatgrinder), or are just odd (e.g., the telephone call). This film had a large enough budget that easily would have allowed for scenes that directly and unequivocally showed the Zone’s supernatural powers, yet all the ones we see are just like that final scene: they are ambiguous and leave a lingering doubt with regards to their mystical content.

Maybe you don’t have this doubt, but I do, and so I can’t avoid this doubt when reflecting on the film. I saw the film long before reading the book, so I pretty much formed my interpretation of the film without input from the book. Maybe this is a good or a bad thing, but I don’t in any way think that Tarkovsky felt his viewers also needed to read the book to fully understand his film. I believe the film is a stand-alone work that can be fully appreciated without referencing the book.

Thank you for writing this article.

Having recently watched this film and read about how highly it is regarded I must admit that I was expecting a bit more – but I enjoyed the film none the less. The unique setting and general weirdness was excellent. I watched Solaris some time ago and liked that film very much.

I’ve always been torn between A Roadside Picnic and Hard to be a God for my favorite work of science fiction. (I’ve only read the two in Russian; not sure if the English translations do them justice). Still, as much as I love the novel, Tarkovsky took it to a whole new level. This film represents two separate iterations of genius.

PS In case you haven’t read “Hard to be a God”, it’s by the same authors as A Roadside Picnic and I *very highly* recommend it. The Strugatsky brothers put all but a very select few sci-fi authors to shame.

Ewan,

This is a most fascinating article! I particularly enjoy your analysis of water within the tributaries of the film’s mind. I am reminded of Tarkovsky’s employment of wet and organic imagery (on Earth) in his adaptation of Lem’s Solaris. This porousness of film ties in well with your concluding comment, “The film is, it would seem, exactly what you make of it,” which I agree with completely.

Cheers,

Sean

I like the attention to visual detail in your analysis, in that way you allow what Tarkovsky wanted which is attention to the image. I usually hesitate from bringing in political aspects into discussions of art films, but in this case, as with other Tarkovsky works, I can only assume the film’s sparseness was partly a kind of artistry born as a response to the restrictive conditions under which it was made. From what I understand, Tarkovsky’s films were made under censorship and with a very small amount of money, allowing for only one or two takes on each scene. To me the most emotional reading of the film, oddly enough, is as a kind of inherently insufficient sci-fi, where the characters seek an alternate, more fantastic world that simply is not penetrable, especially among their bleak surroundings.

Its funny that Tarkovsky’s films have been so thoroughly dissected and rationalized when Tarkovsky himself suggested that their meaning should be left alone. That’s not to say that there should be no discussion, but I think that the language of Tarkovsky’s films is so different and so intuitive that any critique of his work requires a different kind of language as well. These are films that were deigned to be experienced and felt, rather than understood. He’s trafficking in the inexplicable and the intangible. I think that it does him a disservice to recognize this as fact, but quickly move on to business as usual, rationalizing and contextualizing what begs to be left in the ether.

I think you’re right, but I also do not think Tarkovsky meant for his films never to be analyzed. Being so in tune with the human condition he had to know that we desperately seek some kind of explanation for anything we’re confused about. I think what he meant by those statements is to never leave a definite, end all be all, explanation for his films.

The context critics try to surround works of art is generally kind of stupid. Most people who see a work for the first time will never be exposed to it. So they’re left to their own devices to figure out what it means for them. And that’s where the most powerful connection between the artist and his audience is formed. A film like Stalker connects with people in so many different, intangible ways. Tarkovsky intentionally bridged those connections, synthesizing a new concoction of emotion that could never be expressed with a single word.

Great article man. Glad to see that at least someone else has a passion for classic films. Many of my own film classmates wouldn’t even come near this film or any other for that matter unless it featured Seth Rogen or James Franco on the cover.

There’s something unique about Russian films when compared to other foreign films. They will never get as many screenings at an art house theater as say Bicycle Thief or any french wave film due to them being “dry” or whatever else you want to say to knock them. I can’t quite put my finger on exactly what it is. It might be that they are played so stoically. The pace of editing is slow and never pulls any fancy tricks, and for the most part the visuals speak for themselves.

I’d love to give it some more thought. Maybe you have your own opinion on the matter.

Anyways, great article. Looking forward to your next!

On the close of your article you seem to abnegate the authority of your interpretation writing,

“These readings, however, are just that: readings, inferences influenced by the opinions of an individual perspective. […]

The film is, it would seem, exactly what you make of it.”

I don’t know if this conclusion is necessary, especially since the first half of your essay builds substantial evidence for a coherent and authoritative reading of the film, which roots the images within a history of romanticist paintings and which verifies your impressions with quotes from Tarkovsky.

I think that you’re right to allow other viewers their own interpretations, but I was under the impression that your research process granted you particular insights and a sense of intimacy with the film that justify authoritative interpretations.

For example, you highlight the role of nostalgia for Tarkovsky which evinces an intimate knowledge with his on going obsessions in other films. When you write,

“Indeed, Stalker’s remark upon entering the Zone, ‘home at last’, and his consternation upon returning to his family home, embody the term ‘nostalgia’, ‘the pain of the return home’ so central to Tarkovsky’s films”

I get the impression that you are speaking from a place of authority, as one who has entered into the unique symbolic framework of Tarkovsky, as one who understands the particular meaning of ‘home at last,’ ‘nostalgia,’ and ‘the pain of the return home.’

I think that your intimate understanding of those three senses, experiences, or categories is more than enough basis from which you can establish an authoritative interpretation of the film. I think that you do enough work for me the reader, such that I can now look at your evidence to contest and accept claims.

While I respect your restraint and your use of understatement to describe your work as a series of “inferences,” I wish that you had taken the risk of putting yourself out there, to make claims that can be defended underneath the scrutiny of others.

Thank you.

Terrific and insightful review of Tarkovsky’s Stalker. What this film does have in common with the original sourced book is the uplifting universal message of love at end of both. Intended or not. While Roadside Picnic chronicles the obsession on the litter left by a casual stop over of universal travelers, the film concentrates on thematic and scientific possibilities of their leftover garbage on modern life and our natural order thereof. Companion entities.

Great job on this little article. Your insights are impressive and ring true to me. I’m sure that by now you’ve read the book “Zona” by Geoff Dyer that touches on many of the themes and critiques that you mentioned.

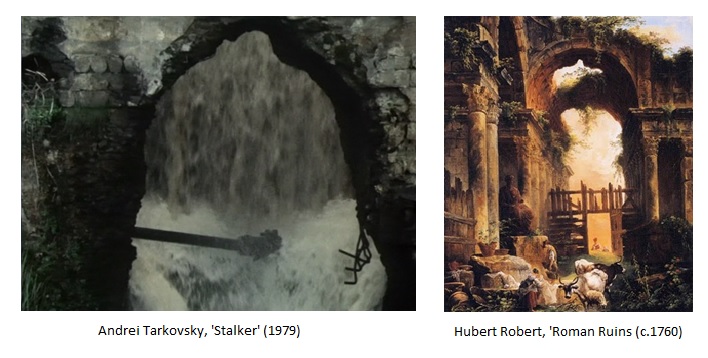

I also applaud your finding the two landscapes by Freidrich and Robert to compare to the stills from the film. That comparative analysis is excellent, and reminded me of another great book that I’m sure you are familiar with, “Landscape and Memory” by Simon Schama.

My personal take on the Zone is that it is essentially a symbol of the primal subconscious mind/spirit/heart within all of us, where things are pure and yet unaffected by language, society, and civilization. It’s where religion can be found for some, and where artists can occasionally tap into to create masterpieces. Hence Stalker’s remark about being home. I know Tarkovsky claims the Zone isn’t a symbol, but I think he is being dismissive of the power of his own subconscious mind over his conscious process of creation. Indeed, where else will we find out what our own deepest subconscious desire is, aside from the subconscious itself?

As Cormac McCarthy suggested in a recent essay (“The Kekule Problem”*), the subconscious couldn’t tell us it’s deepest desires even if we asked, as it is millions of years older than language, and has little use or regard for language. But going to the Zone and entering the room doesn’t require we use words to ask.

Hopefully you find my comment on this years old post — again, I enjoyed reading your great analysis.

*http://nautil.us/issue/47/consciousness/the-kekul-problem

Thank you, Ewan, for this wonderful article. I have been crafting a paper that explores Stalker within the context of the ideas of both Edgar Allan Poe and Walter Benjamin. I will be relating the role of the Stalker to both Poe and Benjamin as I perceive them as all being mediators of the truth, mediators between the material world and the Divine world. I definitely read the Zone as being a type of Eden. Interestingly enough, both Poe and Benjamin write about human refuse and how it may in fact be a sign of rebirth and progress, whatever that may be. Again this article is fantastic.

Dog is Love

Look, it’s very simple…

The Zone is God.

The stalker (or seeker) seeks to commune with God, to bring others to him, and to respect the idea of “thy will be done, not mine” – hence the zone granting wishes in it’s own ways.

The writer seeks inspiration, only to find that God is not it’s true source.

The Professor seeks to destroy God, but ultimately cannot do it.

Dog spelled backwards is God.

This is telling me that this protagonist is pushing dangerous bounds in putting himself in spiritual danger.