The Baby-Sitters Club: Classic, Problematic, or Both?

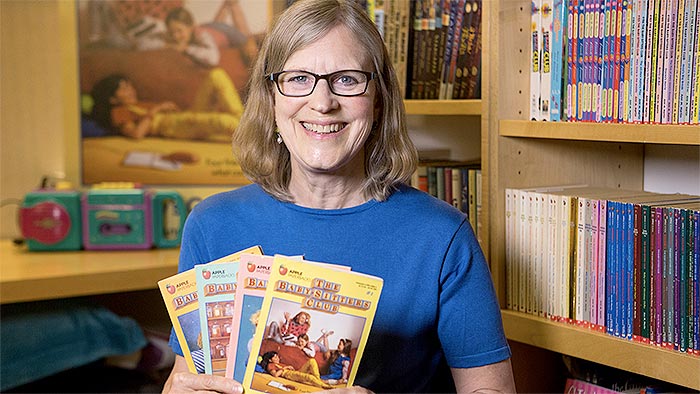

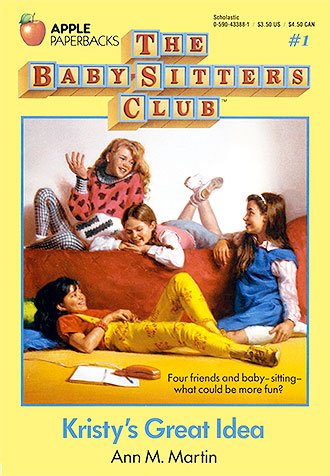

In 1983, Scholastic editor Jean Feiwel approached employee Ann M. Martin with “a glimmer of an idea”–a preteen book series about a babysitters’ club. At the time, a book called Ginny’s Babysitting Job had been one of Scholastic’s bestsellers for several months, despite being “buried” mid-catalogue and having a “rotten cover” (Mental Floss). Ann M. Martin, who had done a lot of babysitting as a kid, ran with the idea, intending to create a four-book miniseries for girls in their preteens and early teens.

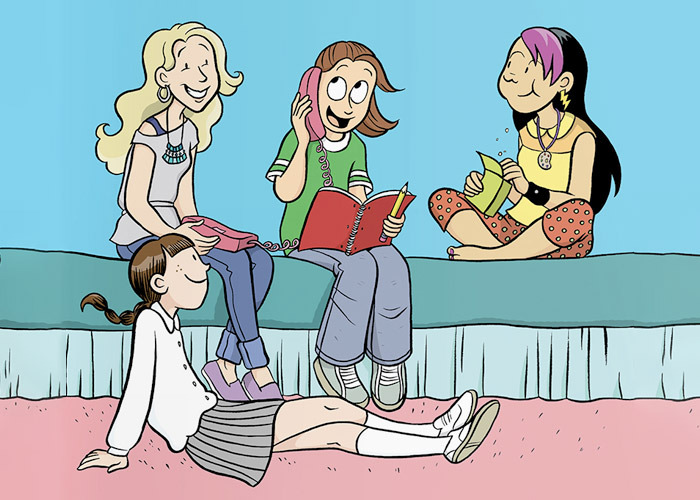

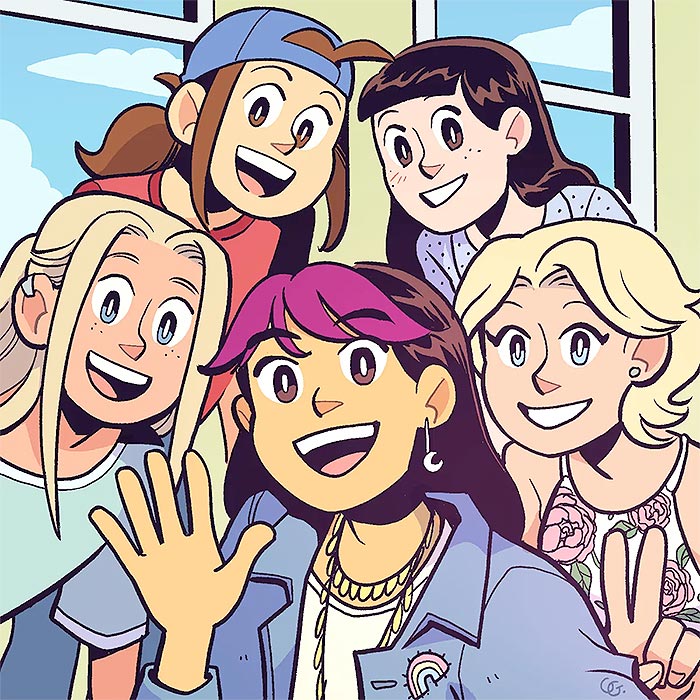

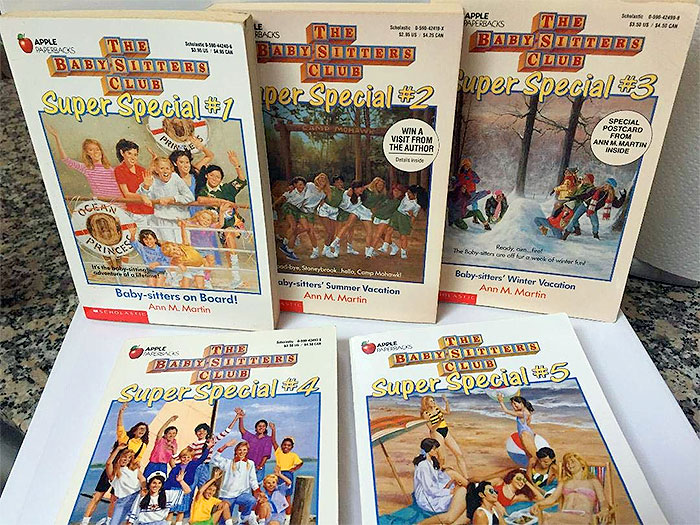

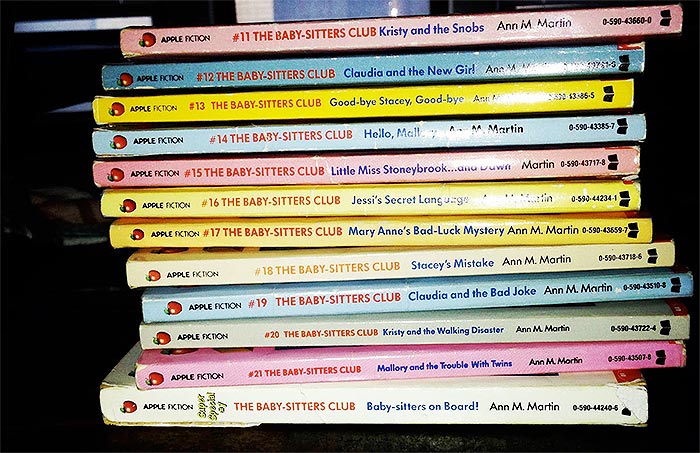

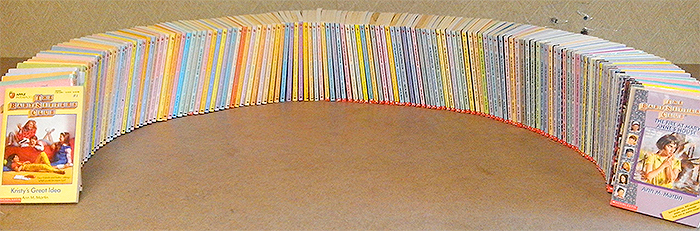

Out of that original idea bloomed a worldwide phenomenon. In 1986, Kristy’s Great Idea premiered. In the next two decades, over a hundred books followed, each featuring one of the seven main sitters in the Baby-Sitters Club (BSC). The books spawned an early ’90s TV series, a 1996 movie, dolls, a game, and honorary BSC memberships for readers. Currently, the BSC is experiencing a resurgence of popularity thanks to an upcoming Netflix series and the retooling of several books into graphic novels. It has been said that horse girls of the ’80s and ’90s had the Saddle Club, mystery-loving girls had Nancy Drew, and business-minded girls had the BSC.

Now that those ’80s and ’90s girls have grown up, many of them, this writer included, look forward to introducing the BSC to their daughters, nieces, granddaughters, and little sisters. There are plenty of male fans, too, like John Green. The current best-selling author praises The Baby-Sitters Club for featuring multifaceted characters who are not “preppy” and who experience a range of realistic emotions, rather than just getting scared of dark caves once in a while (Mental Floss). The books have also been praised for helping male and female readers deal with friendship troubles, grief, or even disease. For instance, some readers report that reading about Stacey McGill’s struggles with juvenile diabetes helped them get diagnosed.

That said, some parts of The Baby-Sitters Club arguably haven’t aged well. Some former readers claim the club functions almost as a “cult,” and go on Internet forums to snark about some of the BSC members’ more odd or unrealistic behavior. Parents and guardians, too, may have reason to look askance at how the series portrays certain people and situations. Thus, the question becomes, is this series the classic that nostalgic readers praise it as? Is it irredeemably problematic? Careful analysis suggests the answer is “a mix of both.”

“Classic”: The BSC’s Positive Side

Plenty of former readers hail The Baby-Sitters’ Club as a classic series. They may not have read every book. They might not have liked all the books they did read, and they probably identified more with certain characters and plots than others. Yet even the series’ detractors probably have at least one positive memory of the BSC, whether it was the characters themselves or the situations they encountered. Many readers say the BSC taught them lessons about friendship, entrepreneurship, and people in general that they may not have learned quite the same way otherwise.

Familial Diversity and Associated Conflicts

Before The Baby-Sitters’ Club, it was somewhat uncommon to see anything other than the traditional nuclear family portrayed in fiction. Thus, readers who had a mother, father, and biological siblings could easily identify with characters. Yet, while readers from other types of families might identify with characters based on interests or personalities, they were often left out. The same is true for non-white families, families with adoptees, or particularly large families (five children or more). One thing that makes the BSC so enduring then, is how they and their families broke ground in portraying non-traditional, diverse households.

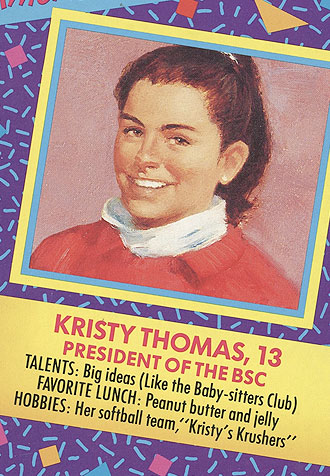

Ann M. Martin created the first four baby-sitters with her class in mind. She had been a teacher and encountered students of diverse backgrounds, so she wanted her characters to reflect that, especially regarding family situations. Many students came from blended families, but in the 1980s, divorce and family blending were still fairly new concepts for a lot of young people. Thus, Kristy and Stacey–half of the original cast–came from families affected by divorce. Kristy was part of a blended family, while Stacey had moved to Stoneybrook, Connecticut from her beloved New York City with a now-single mother. Later, the BSC would host one more blended family member, Dawn, who would also become original character Mary Anne’s stepsister.

As for Claudia and Mary Anne, the other two of the original four baby-sitters came from traditional nuclear families. However, Mary Anne’s mother dies before the series outset, and her single father raises her in a somewhat authoritarian way. For her part, Claudia comes from a multi-generational household, sharing a home with her parents, older sister, and her grandmother “Mimi.” Mimi is first-generation Japanese, and gives Claudia a direct connection to her culture in predominantly white Stoneybrook. She’s also a somewhat unusual presence in a book series aimed at readers for whom multi-generational living might not be the norm. This familial diversity gives readers more opportunities to identify with the four original characters and their situations, if not their skin colors or cultures (three out of four original characters are white, assumed to be white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs).

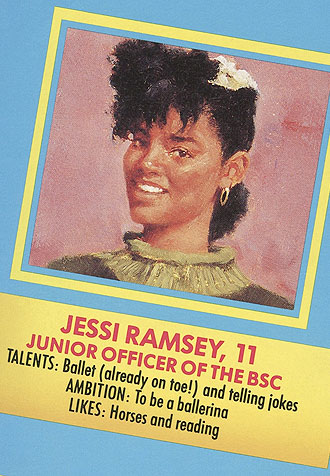

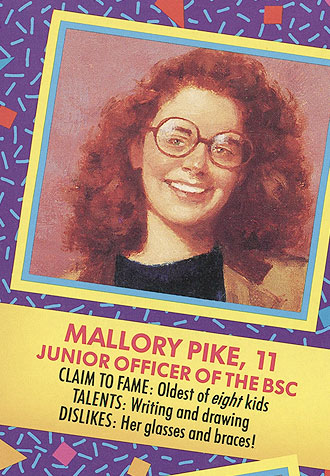

In later years, Ann M. Martin would expand familial diversity, as well as the associated situations the BSC girls would experience. As noted, Mary Anne’s father remarries fairly early in the series, finding love with Californian Sharon Schafer and giving Mary Anne a stepsister in fellow BSC member Dawn. (Mary Anne also gains a young stepbrother in Jeff, but he lives in CA with his dad and is not seen often). The BSC also gains Abby, who, like Mary Anne, has lost a parent. Her father died in a car accident when she was nine, and she and her twin sister Anna moved to Stoneybrook from Long Island with their widowed mother. Jessi and Mallory, “junior members” at age 11, come from nuclear families with their own types of diversity. Mallory is the oldest of eight, which is unusual for Stoneybrook. Jessi’s family, originally from the diverse Oakley, New Jersey, is one of the only black families in Stoneybrook.

Combined, the seven BSC members present readers with several backgrounds in which they might find themselves. Additionally, the BSC girls go through several associated family conflicts readers might have experienced. Kristy presents her blended family as an improvement over her biological parents’ fractured relationship, but she often struggles with her new role in said blend. That is, she was originally a middle child and only girl with three brothers–Sam and Charlie older, David Michael younger. When her mother Elizabeth married Watson Brewer, she gained three additional younger siblings, Karen, Andrew, and Emily Michelle. In many situations, Kristy is called on to act as an oldest child and almost a third adult since she is usually a reliable babysitter. She takes this in stride, constantly coming up with “famous great ideas” to occupy the kids and entertain her friends at the same time. However, she rarely seems to get time to be by herself or act like a young teen. This feeds into her tendency toward bossiness, perfectionism, and self-righteous behavior. On the other hand, Kristy’s experiences help her develop leadership skills and make her trajectory as a young businesswoman more realistic. They also make her relatable to readers who’ve had to grow up faster than is typical for whatever reason.

Similarly, Stacey and Dawn face diverse conflicts as kids affected by divorce. When Stacey is diagnosed with juvenile diabetes, her parents blame each other and get into bitter fights. In one book, the associated stress causes Stacey to be less than careful about her insulin and food intake. When she ends up in the hospital, Mom and Dad blame her for the situation, heedless of their own parts in it. Dawn, too, gets pulled between her parents as they pressure her to make a permanent decision about where to live and with whom. Dawn spends several books vacillating between California and Connecticut until finally deciding to move back to CA permanently. Even devoted former readers report hating this cycle, partly because Dawn comes across melodramatic, but also because her parents placed her in the position of losing touch with all her friends on one side of the country or the other. That said, both Dawn and Stacey’s journeys do a good job of pointing out how life-altering divorce and family blending can be. Whether or not they’ve moved across the country, a lot of readers from blended families have probably had to give up the things and people they treasure as they adjust to new situations.

Relatable sibling conflicts are common for the BSC, too, and some of them are fairly high-stakes. The best example might be Claudia, who is the younger sister to Janine, a “certified genius.” Janine’s IQ is in the 190s, and she spends a lot of time working on complex science and math assignments or dropping large vocabulary words into everyday conversation. In contrast, Claudia struggles in school, to the point she is left back a grade for part of the series. She has suspected learning disabilities but is never tested for any. In addition, while Claudia’s parents don’t openly favor her sister, they don’t pay as much positive attention to Claudia. They outright discount or forbid her interests, such as Nancy Drew books (too simplistic and “mainstream”) and junk food (too unhealthy). Claudia is only truly close to Grandma Mimi, who unfortunately dies early in the series. At one point after Mimi’s death, Claudia actually suspects she’s adopted. Claudia and the Great Search devotes an entire plot to this. Rather than treating Claudia’s adoption theory as comedic, as some authors might do, Ann M. Martin takes a serious approach. She delves into why Claudia feels alienated from her family, and the fact that while discovering her life is a lie would be scary, it might bring Claudia a sense of relief and vindication. When Claudia is reassured she is indeed a biological part of her family, her parents and sister “wake up” to how she feels. Their relationships don’t become perfect, but Claudia is treated with more empathy and understanding. Part of this involves her parents praising and encouraging her artistic interests along with Janine’s academic ones.

Loss and Trauma

Ann M. Martin’s series was not the first in which characters experienced loss and trauma. However, until The Baby-Sitters’ Club, readers in the target demographic may have been largely sheltered from those themes. Children’s and adolescent literature that did deal with loss tended to do so when the deceased characters, often parents, were already off-page. As for traumas such as custody battles or time in the foster care system, they were rarely touched on. Again, these were not “ideal” situations for children, and so parents, teachers, and authors felt the need to protect them. But Ann M. Martin knew that giving readers a safe way to interact with loss and trauma might help them face it in the real world, whether or not they experienced what her characters did.

Martin continues her trajectory of tackling serious issues in kid-friendly ways with Abby and Mary Anne, the two BSC members with deceased parents. The girls’ loss experiences and personalities are vastly different, giving readers two distinct portraits of dealing with grief. Abby is a sanguine, bold girl who likes to keep busy. She’s always moving, whether that’s because she’s playing sports or doing BSC activities. Thus, she doesn’t always present as a person who’s experienced grief or who lets it affect her. But unlike Mary Anne, who never knew her mother, Abby lost her dad at age nine, a mere four years before joining the BSC. She had time to develop a relationship with her dad, and from her autobiography Abby’s Book, readers know said relationship was quite close. When the loss does come up, such as while Abby writes her autobiography or prepares for her bat mitzvah, the sting remains raw. Sometimes, the loss plays into Abby’s personality, as she uses sanguine methods to cover her emotions. This sometimes helps her build connections with baby-sitting charges, such as foster child Lou McNally, who has lost both parents and was briefly separated from her brother in the system.

Mary Anne is almost diametrically opposed to Abby in the way she deals with family loss and conflict. She’s the more melancholic of the two, known for being serious, studious, and quiet. Additionally, Mary Anne is intensely sensitive, to the point that her crying is somewhat famous among her friends. She’s not a crybaby or obviously immature, but anything that could make a person cry, from sad movies to harsh criticism, will probably bring on tears for Mary Anne. She’s also a somewhat extreme introvert; her autobiography Mary Anne’s Book reveals performing in a ballet recital at age six made her so anxious she was physically ill.

Mary Anne’s friends don’t chalk any of this up to the loss of her mother. It’s simply who Mary Anne is, and she’s accepted that way, which is great for the characters and readers alike. However, when the BSC is introduced in each book, it’s always brought up that Mary Anne’s mother died when she was a baby. Adult readers such as this writer have found this lends deeper perspective to Mary Anne. That is, perhaps she inherited introversion and sensitivity from her mom, so some of her personality is “natural.” But she also grew up without her mom’s influence, and her father was strict and overprotective with her. In Mary Anne and the Secret of the Attic, Martin reveals Mary Anne’s dad was devastated at his wife’s death, so much so he left Mary Anne with her maternal grandparents for a while. When he expressed desire to raise her, the grandparents fought him for custody. Martin directly attributes Dad’s authoritarian behavior to the trauma; he was afraid if he “messed up,” Mary Anne’s grandparents would take her back. While Mary Anne was too young to remember the trauma, adult readers can guess how it might have made her shyer and more withdrawn than normal. In fact, late in the series, we see Mary Anne experiencing depression and receiving therapy, in part to deal with the past. Martin took something of a risk with such a mature arc, but it works because it helps Mary Anne grow into a stabilizing force for her friends and the Baby-Sitters’ Club as an organization. Additionally, the arc never becomes so dark or hopeless that readers can’t find some way to relate or sympathize.

Bullying and “Othering”

Statistics from sources like bullying.gov tell us bullying has been a serious issue for decades and sadly remains so for a lot of kids. Any kid with a noticeable difference, such as non-white race, a disability, or an outward marker of a religion such as a hijab, can be a target. Kids can also be targeted because their appearances aren’t ideal, or because they pursue interests outside what their peers think of as “normal.” Thus, Ann M. Martin didn’t tackle new issues when she let the BSC deal with bullying and “othering.” But in a move ahead of her time, she plumbed the depths of how and why it happens, and what strong, self-determined characters could do about it.

As for Jessi and Mallory, they might be younger than most BSC members but are not to be left out. Their familial diversity provides touchstones for readers and feed into the overarching themes of friendship and coming of age, too. Interestingly, like Stacey, Kristy and Dawn with family blending, or Abby and Mary Anne with parental loss, Jessi and Mallory’s arcs have similar trajectories. Both girls are gifted in the arts for their ages; Jessi is a promising ballerina and Mallory a talented writer with a keen interest in children’s and preteen literature. Both girls are unusually imaginative. When they are alone together, they sometimes play pretend games in which they take on different, well-developed personas (pretending to be historical immigrants rather than Disney princesses, for instance). They, especially Mallory, tend to draw into their own worlds at times, Jessi through dance and Mallory through world building.

Such creativity sometimes sets the girls apart from family and peers in a negative way, including fellow BSC members. Jessi and Mallory may be mature enough to babysit younger kids and hang out with thirteen-year-olds, but there is still a two-year age gap. It’s not obvious in most books, but sixth-graders are in a different place than eighth-graders developmentally and emotionally, and sometimes this is felt. Mallory and Jessi, for instance, are not allowed to stay out as late as the other girls or participate in certain activities. When the older girls go on mother’s helper trips, for instance, the younger two are sometimes left behind. The girls’ parents are quite strict in terms of what their daughters can wear; Mallory is well over eleven before her mom and dad will let her pierce her ears, and Jessi, too, is expected to dress conservatively. Additionally, both girls are expected to take on full responsibility for their younger siblings on many occasions. However, that responsibility often doesn’t translate into how much independence they’re allowed to exert over their lives. Therefore, Jessi and Mallory are often left out of the loop when the older girls wear “cool” clothes, discuss boys, or participate in eighth-grade activities.

However, Jessi and Mallory’s “otherness” is not always because of age or parental protectiveness. Both of these are understandable from an adult perspective, although the youngest readers might empathize with the girls for thinking the parents and older friends are overprotective. What is less understandable is how Jessi and Mallory are otherwise treated. Jessi’s blackness, for instance, is often the target of racism, making her “othered” on two counts. Even in dance school, she is “othered” as a gifted dancer, but one who is still too young for certain roles or responsibilities. Meanwhile, Mallory is often a bullying target. Mallory wears braces and glasses, and is pictured with naturally curly red hair. Her appearance contributes to the bullying, damaging her self-esteem (she often reflects that she is less pretty than her friends). But Mallory’s personality contributes, too. She’s targeted for being bookish, somewhat shy, and as bullies label her natural clumsiness, “spastic.” Being the oldest of eight doesn’t help; like Kristy, Mallory is often expected to act like a miniature adult and be an example to her siblings. Her parents often overlook that Mallory’s still a kid, while simultaneously treating her as if she’s too immature to express selfhood or independence.

Martin takes another interesting, mature tack when dealing with Mallory and Jessi’s “othering” at the hands of Stoneybrook. Namely, both girls are faced with decisions to move into other environments. Jessi is offered a position at a prestigious year-round ballet school, and Mallory searches out an alternative boarding school after intense, ongoing bullying throws her into depression. Both schools would let the girls express their creativity and pursue passions with like-minded people, but it would mean leaving everything and everyone familiar. Jessi and Mallory, then, are faced with big decisions for their ages, ones with more facets and consequences than they’re used to. Readers are invited to explore the facets with them, and perhaps consider what they would do. This opens the door for increased empathy and a “safe” way to explore intense decisions.

Interestingly, Jessi and Mallory take opposite paths. Jessi decides to forego the dance school in exchange for more advanced instruction close to home. Conversely, Mallory transfers to Riverbend Hall, meaning she’ll live in Massachusetts full time and be an honorary BSC member. Both decisions are presented as positive and a way to show friends can take different paths without growing apart. There’s also a deeper layer in how the girls choose to handle “othering.” Mallory chooses to leave, perhaps to craft an identity outside a big family and a somewhat stereotyped characterization. Jessi chooses to stay, perhaps because her home environment has taught her she is already safe, secure, and allowed to grow in uniqueness. Either way, readers get the message that it’s good to seek your tribe and fulfillment, wherever it may be. They get the message that these things can be found anywhere.

Increased Knowledge and Empathy

Accepting diversity, dealing with trauma, and standing up to bullies is all well and good, you might say. Yet does The Baby-Sitters’ Club prove itself “classic” in how the characters grow and mature? The answer is an enthusiastic “yes.” The BSC girls range in age from 11 to 13, but often act wiser than their years. As we’ll see later, this can be positive and negative. Often though, it’s positive, as the girls glean experience that will help them navigate the wider world.

Yet another of The Baby-Sitters’ Club‘s positive points is how its characters gain knowledge and empathy for situations outside their reference frames. In babysitting almost every kid in Stoneybrook, the BSC girls encounter new levels of diversity, and learn how to respond to unfamiliar, potentially disconcerting situations. Some of these, the girls can solve themselves, while others take adult and community involvement. All the endings are positive, if not “happy,” but refreshingly, not everything is always tied up with a pretty bow.

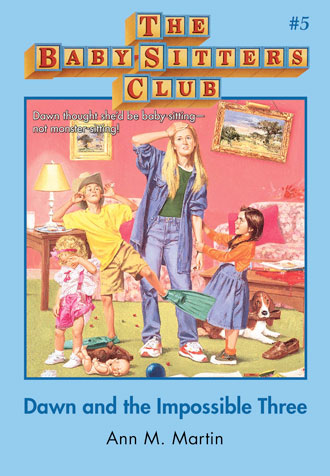

A lot of the diversity BSC members encounter comes from their young charges. “Diversity” can mean everything from race and culture to disability and illness to outright dysfunction. In Dawn and the Impossible Three, for instance, Dawn is faced with babysitting the unruly Barrett kids. Their mother, while well-meaning, is consumed with work and the fallout of a recent divorce. Thus, she’s overly dependent on Dawn and neglects to share important information with her, such as toddler Marnie’s chocolate allergy. Had Mallory not jumped in at a BSC picnic, Dawn would’ve unknowingly given Marnie a brownie, which would’ve made her sick. Mrs. Barrett later neglects to share her custody arrangement with Dawn, leading babysitter and community adults to fear oldest child Buddy is the victim of a family abduction. In reality, it was legitimately Mr. Barrett’s weekend to have the kids, but he took advantage of Dawn’s ignorance to pick up Buddy without her knowledge and frighten his flighty ex. In response, the community comes together to find Buddy, and Dawn is able to confront the Barretts with adult support. Dawn’s experience as the child of divorce gives her extra gravitas and empathy.

In a more serious example of diversity and dysfunction, Claudia encounters an abusive father in Claudia and the Terrible Truth. At first, she’s unsure, figuring little Joey and Nate are just unusually good kids, if a little anxious. But then she finds out Dad has thrown away the boys’ stuffed animals because they’re “babyish,” and overhears him slapping one of the boys in the face. Gobsmacked and scared, she turns to her mother, who engineers a plan to get the boys and their mother to safety at a relative’s home. In the meantime, Claudia gets a crash course in harsh reality mixed with knowledge and empathy. She has often complained about her family’s strictness, not without reason, but admits during the book that she has been blessed and loved. Having never encountered blatant abuse before, she also learns what signs to watch for, and how to relate best to kids like Joey and Nate. Specifically, the exuberant Claudia quickly learns to be a bit gentler and more circumspect than she would usually be with these boys.

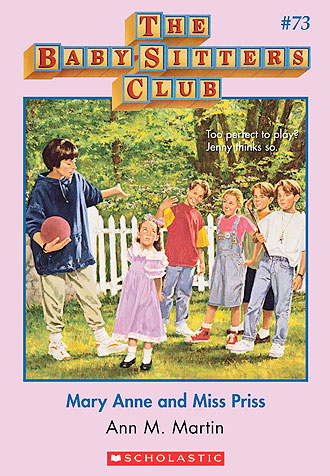

It doesn’t take abuse or dysfunction for the BSC girls to grow, though. Sometimes their charges impart lessons that seem lighthearted or comedic, but contain “layers.” One great example occurs in Mary Anne and Miss Priss. This book sees Mary Anne becoming a frequent sitter for four-year-old Jenny Prezzioso, one of the BSC’s least favorite charges. Jenny is spoiled to the point of absolute power over her parents, especially her mother. As it’s once explained, if Jenny has a tantrum, Mom will pick her up, kiss her, and give her ice cream or candy, or promise to buy her whatever she wants in the moment. It would seem, then, that shy Mary Anne is a bad match for Jenny. At first, that assessment proves correct, as Mary Anne tries unsuccessfully to get Jenny to socialize with other kids and play games like kickball, which Jenny won’t do because they’re “messy” and would damage her clothing (she’s always in frilly, lacy dresses and Mary Janes, regardless of weather or activity).

In time though, readers see Mary Anne is the perfect person to find the heart of Jenny’s issues and respond. She learns Jenny’s baby sister Andrea already has a lucrative career as an infant model. Everywhere Mrs. P and her daughters go, Andrea is hailed as cute, beautiful, or precious. Jenny is barely noticed, let alone acknowledged. Eventually, Jenny becomes so despondent, she determines to try modeling, too. Her attempt is a flop; unlike Andrea, she’s expected to recite lines and act, which she’s never done. Thus, her efforts come off too stiff for the exacting modeling agency. Her overall behavior and prissiness worsen.

Of course, it’s hard to get a four-year-old to express why they’re doing something, let alone open up about emotions they may not understand fully. But Mary Anne is able to draw Jenny out more than her parents or any other sitter. She gets Jenny to express the fear that her parents love Andrea more, and that she does things like dressing in frills and keeping neat so her parents will be pleased. This prompts a gentle but pointed conversation with Mrs. P, wherein Mary Anne respectfully advocates for Jenny. Keep in mind, Mary Anne was a child who, at Jenny’s age, was also under pressure to act “perfect” and please an anxious parent. She doesn’t make that connection directly, but adult readers can applaud Ann Martin for the depth of the arc once again.

Finally, the BSC grows in wisdom and empathy outside of charge relations, too. They have the friendship fights expected of young teens, some of which are serious. But they also commit to seeing each other through everything. Perhaps the best example comes from Stacey’s juvenile diabetes. Martin doesn’t always write this issue well, but Stacey’s friends are always accepting of her needs. They encourage her to stay open about her condition and practice self-care, even when she doesn’t want to. In the movie, for instance, Stacey refuses to tell a new boyfriend about her diabetes. The others insist that if he truly likes her, he won’t care, and they’re proven correct. In the books, the other girls also master the balance between looking out for Stacey and hovering over her. They might remind her to eat or take insulin if she looks or acts ill, but don’t push. Claudia, queen of junk food, always has snacks on hand Stacey can eat, from veggies to wheat crackers. And while Stacey’s parents might not let her vent about the hardships of diabetes, her BSC friends allow her to feel and express what she needs to in the moment. These are great messages for readers dealing with illnesses or disabilities, who may struggle with feeling accepted or identified by something other than their limitations.

Problematic: Trouble Spots in the Series

As popular as The Baby-Sitters’ Club was and is, the series does have some negative points. Looking at the books from an adult perspective, the most enthusiastic former readers might admit a lot of individual books have trouble spots. This writer is one such reader. Although she enjoyed the BSC books as a kid, she remembers her parents didn’t exactly approve of some of the characters’ actions or situations. As an adult, she sees those same issues and is eager to approach them with critical thinking. None of the trouble spots completely negate The Baby-Sitters’ Club’s positive elements, but they are well worth examining, particularly since the series advent was 34 years ago.

“Cultish” Behavior

Former readers who’ve learned to dislike The Baby-Sitters’ Club often compare the club to a cult. They claim Stoneybrook residents are under the thrall of the BSC, and there is no other reason any sane parent would leave their young children alone with thirteen-year-old girls. This reaction is probably exaggerated, and reveals detractors aren’t clear on what a cult actually is (a religious sect in which a leader sets themselves up as infallible or a god). With that said, the BSC is so insular, concerns about their behavior are not totally unwarranted.

The actual truth of the “cult” accusation depends on who you ask, but it’s not without evidence. As the group president and leader, Kristy is often pegged as the worst offender. Readers point out how the rest of the group is expected to go along with her ideas no matter how unrealistic or problematic they are–and sometimes, they are extremely so. In the movie, for instance, Kristy decides the Stoneybrook kids need a five-day-a-week day camp that runs from ten to four. She expects all their current babysitting charges, plus new kids, to come, and parents to pay fairly expensive tuition. She organizes activities to the umpteenth degree with no input from anyone else, volunteers the Schafer-Spier family’s huge property with implicit permission, and runs afoul of a neighbor, but expects to be treated like she is in the right. The day camp is successful, in the sense that the kids enjoy it. But there are myriad problems, such as kids lined up constantly for one bathroom, getting into accidents, and causing noise issues. One scene played for laughs shows over half the charges in the same time-out area–with apparently one supervising sitter. Throughout all this, the day camp is treated as Kristy’s brilliant brainchild.

Kristy is not the only offender, though. Another example puts Claudia in an antagonistic position. When Mallory becomes old enough to be a junior member, the five original members decide to put her through an “audition.” They ask her myriad questions whose difficulty borders on ridiculous, but Claudia actually asks Mallory to draw an accurate picture of a child’s digestive system. Why Claudia, who hates school herself, would ask this is a mystery, as is why she would think proper baby-sitters should know what a digestive system looks like. But she does, and ridicules Mallory for “failing.” Worse, the other girls concur with Claudia and try to keep Mallory out of the club. Again, this raises a mysterious question–why would these girls, some of whom have been bullied or ostracized, and who pride themselves on treating children with fairness, bully a prospective member? Keep in mind, Mallory had also been a well-behaved charge and reliable honorary sitter for at least a year to that point, helping the attending sitter whenever her siblings needed the BSC’s services.

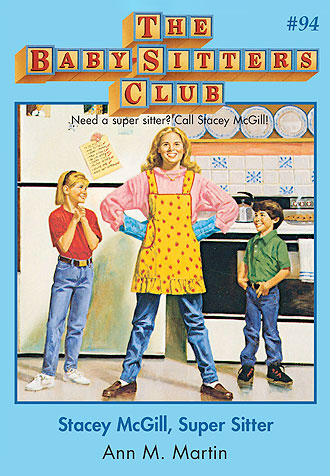

Overall, the members tend to act “cultish” toward each other about the club at various points. One crucial book sees Stacey quit because she thinks she’s outgrowing the BSC. She blows up at Kristy–“Everything you don’t think of is stupid. I’m sick of the meetings and the dues and the Kid-Kits–all of it.” She also brings up the intense commitment level the club requires–meetings three days a week, wherein almost no excuse except illness is acceptable for absence, babysitting jobs on afternoons, evenings, and weekends, constant holiday trips, and so on. Stacey points out some of the charges are toddlers or even babies, who can be almost impossible to take care of alone. Yet, Stacey is presented as wholly antagonistic. In place of the BSC, she gets involved with some known troublemakers, which puts her in the position of choosing the “good” BSC over an automatically “bad” friend group, rather than a friend group who could nurture her without added expectations. Stacey is the one expected to apologize and ask forgiveness, while the other members are not (although they may pay lip service to their part in the conflict). This sends the message that the BSC are Stacey’s only true friends, and that clubs engaging in the BSC’s behavior, questionable or not, are justified. Worse, some of Stacey’s concerns are not adequately addressed, even much later in the series. A late book, Stacey McGill, Super Sitter, has her not only babysitting for a new family, but practically acting as their cook and housekeeper–with implicit encouragement from Kristy and the others.

Act Your Age–Or Not?

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, the BSC members were held up as models of young, responsible entrepreneurs. They were also lauded as good examples of steadfast friendship. For this writer, the friendship and level of independence the BSC girls experienced were #goals. But especially in 2020, the girls’ level of independence hasn’t exactly aged well.

Many readers, particularly adults, find problems with how old the BSC acts. Especially in 2020, some of the girls’ regular behavior hasn’t held up. As noted, for instance, they are often expected and trusted to babysit infants or young toddlers alone. Keep in mind, these girls are thirteen, not even out of junior high. In Mallory and Jessi’s case, they are often asked to babysit eight- and nine-year-olds, kids who are only a few years younger and could easily railroad them. In the Super Special books in particular, the BSC is seen acting as primary caregivers on cruises, out of state, and on a cross-country RV trip (parents were present for the latter, but left the girls almost entirely in charge on various occasions). The BSC girls are allowed to go anywhere they please on their own, including new states and foreign countries, with minimal parental input. Granted, the series was written in the late ’80s and ’90s, but even then, kids thirteen and under were not so free-range. The underlying message is deceptive at best. This writer, who has cerebral palsy and was highly under parental protection at the BSC’s age, remembers reading certain books and feeling envious or lesser because she did not have the BSC’s independence, nor were disabled teens represented in any way. The closest example, Stacey’s diabetes, does not keep her from experiencing almost total, and age-inappropriate, freedom.

Additionally, the BSC members often engage in non-babysitting activity or development that makes them seem more like high school juniors or seniors. All the girls have steady boyfriends throughout various books, including Jessi and Mallory (granted, in their cases, these are more “special dates” for things like school dances). Mary Anne’s relationship with Logan Bruno, in fact, lasts throughout the series and is treated almost like a monogamous arrangement. Similarly, the girls’ homework assignments and school expectations are written as if for much older kids, such that readers don’t wonder why Claudia in particular struggles. One assignment requires eighth-graders to write their life stories for English class, with points taken or given not only for spelling and grammar, but overall “depth.” With the exception of chronic or serious issues like abuse, the girls are almost expected to solve every problem on their own. Again, this was probably meant as promotion of independence or female empowerment originally. Now though, these situations make former and current readers wonder what the parents and teachers were thinking.

At times, the parents and teachers of Stoneybrook act so out of touch that the BSC girls get into potentially damaging, if not dangerous, situations. One egregious case occurs in Dawn and the Older Boy, wherein Dawn meets Travis, an arrestingly good-looking guy who’s from California, enjoys health food, and appears to share common interests with Dawn. The problem is, Travis is 17 years old. The four-year age gap is significant for someone Dawn’s age, and only serves to highlight Travis’ controlling, emotionally abusive nature.

Today, any attentive parent or teacher would see the red flags in Dawn and Travis’ relationship and intervene right away. In BSC world though, it’s mostly Dawn’s friends encouraging her to get away from Travis. It’s good that Dawn’s friends support her, but even the tightest-knit group of eighth-graders would never be a match for a charismatic high school senior. The premise of the book ends up being unrealistic and, depending on the reader, dangerously enticing or scary.

Similar issues occur among the other girls throughout the series, although thankfully, most are not as dangerous. In Claudia and the Middle School Mystery, for instance, Claudia is accused of cheating on a test. She will face severe consequences at school and almost draconian ones at home, considering how seriously her family takes academic achievement. But despite Claudia’s clean record, and despite the fact that she spent hours studying for that test–one of the only ones on which we see her get a decent grade–her parents only say they would “like” to believe her. Their distrust persists throughout the book. It is only when Janine, the genius older sister, sticks up for Claudia that Mom and Dad reconsider. This sends Claudia the message that Janine is trustworthy, but she is not. It also reinforces favoritism toward Janine and tells Claudia adults will only ever see her as an academic failure; therefore, they are not trustworthy.

Perhaps most disturbingly, the BSC members do not get needed adult intervention even when bad situations persist for months or (assumed) years. (The nature of the series means the girls don’t age at a normal pace, making it hard to place events in the span of a year or two). Mallory is probably the best and worst example. Throughout the series, she’s the target of student and teacher bullies. This runs the gamut from boys in her co-ed gym class lobbing volleyballs at her head, to an anti-feminist teacher refusing to call on Mallory or any other girls or answer questions from girls. It takes an entire book for Mallory to get up the nerve to confront the teacher, and again, her fellow teenagers are the ones offering the most support. Her parents seem to allow these and other negative situations, such as the backlash Mallory gets when her dad loses his job, to go on unnoticed. It reaches the point that Mallory experiences isolation and depression, and considers changing schools–but she is the one looking up alternative schools and scholarships, completely on her own.

Again, there is nothing wrong with promoting empowerment, perhaps especially to preteen and teen readers who are crafting their own identities. The problem with The Baby-Sitters’ Club version of this is, the members’ friendships are treated as a primary support system, and adults remain largely unaware of the members’ thoughts, feelings, and concerns. This is a ton of pressure to put on real-life readers, many of whom know from experience their friends are not as mature or reliable as the BSC. Again, while Ann M. Martin does occasionally temper her independence message with appropriate adult support, it happens far less often than many 2020 adults feel it should.

Pigeonholed Diversity

Diversity is wonderful, and in 2020, we are more positive and vocal about it than we’ve perhaps ever been. Unfortunately, diversity doesn’t always mean true inclusion and belonging. For Ann M. Martin and the BSC, it sometimes meant something as simple as white characters having one or two non-white friends, or using one-off disabled characters as lessons in compassion.

Ann M. Martin did a great job of presenting the BSC with diverse charges and opportunities for growth. We can commend her for dealing with topics like divorce and family blending, chronic illness, and racism at a time when these were still not common in adolescent literature. But the discerning adult reader will soon see part of that commendation comes from a nostalgia filter. Taken as a whole, the series’ diversity is lacking in several respects. One could call it “pigeonholed,” as in, only coming up when it directly drives the plot, or when a BSC member (usually white, middle-class, and/or able-bodied) needs to learn a particular lesson. More disheartening, this occurs across almost all diversity examples.

Jessi is probably the most egregious and best-remembered example. TV Tropes describes her as the “Token Black,” and indeed, she is the only BSC member of color (Japanese-American Claudia’s heritage is mentioned, but she is treated more like a white person, unless something specific brings up said heritage, like a tour of Pearl Harbor). When the BSC members are introduced anew in every book, Jessi’s race is always brought up first. Whether the book is from Jessi’s POV or not, the narrator will invariably mention she faced racism when she first moved to Stoneybrook from Oakley, NJ. If the book is from Jessi’s POV, she will bring up her new town’s lack of diversity or how different she feels. Yet, Jessi is rarely if ever seen having a meaningful friendship with another black preteen. Her blackness is never discussed as part of her identity, unless it’s for a “special” reason like a book that shows her preparing for Kwanzaa (and educating white friends who think it’s a racist holiday). Jessi’s illustrations usually show her with light brown skin–in some, she is almost white. Her hair often looks more curly than textured, if it’s down at all. Additionally, Jessi takes every misunderstanding of black culture as racism; when a young child is reluctant to eat hoppin’ John, for instance, she takes somewhat personal offense. If Ann M. Martin’s intention was to avoid making Jessi “other,” she failed miserably. Instead, she “erases” Jessi or makes her an anti-racism spokesperson almost 100% of the time.

Something similar happens with Claudia and Abby, the other two minority BSC members. As mentioned, Claudia is Japanese-American, while Abby is Jewish. Neither girl is written as though her heritage is important. In fact, for Claudia, being Japanese is often painted as negative. Her parents and sister are defined almost entirely as academicians, feeding the stereotype that Asians are geniuses. Her parents’ mentioned strictness toward Claudia could be seen as feeding the idea that Asian parents are inscrutable and less loving than typical Western, WASP parents. Even when Claudia’s heritage is presented as positive, Ann Martin tends to stereotype her. For instance, Claudia is called “exotic” when her appearance is described, and much is made of her “almond-shaped eyes” and long, luscious black hair. Claudia is definitely attractive, but the “exotic” descriptor is like a neon arrow pointing at her screaming, “FOREIGN.” Pair that with her penchant for colorful, “sophisticated” clothes and a lithe, thin body, and Claudia comes across as a picture of stereotypical Asian perfection.

As for Abby, she suffers from what TV Tropes calls “Informed Judaism.” We know she’s Jewish because she says so on a couple occasions, but it’s never a big part of her identity. Her bat mitzvah is a big part of one book, but it’s a subplot to Abby inadvertently cheating on a test and lying about her subsequent suspension. At face value, this is a good setup. The bat mitzvah implies Abby is a woman in the eyes of Jewish culture and thus, responsible for her actions. Cheating is an irresponsible and immature thing to do, so naturally Abby would have conflict about that. The problem is, because her Jewish heritage is so rarely brought up, this plot could be construed as Abby playing to negative stereotypes of Jews. Namely, readers could see this as a failed attempt to do well in school, or a sign that Abby would cheat and “steal” from others regularly if she thought she could (the unfortunate trope Greedy Jew). Worse, Abby’s Jewishness is never part of a major positive plot. She doesn’t mention synagogue attendance, Shabbat, Hebrew school, or any other activities a Jewish girl might participate in. We have no evidence of her family keeping kosher, and she is never seen celebrating Hanukkah, Passover, or any other holidays, though they are mentioned in passing. Once again, Ann M. Martin takes a minority character and effectively “erases” her for the sake of focusing on the club as a whole, a club that, again, has a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant majority.

Inspiration Porn

“Inspiration porn” is defined as “the objectifying of a disabled person for the benefit of non-disabled people,” or, holding up a disabled person as inspirational or a hero for doing everyday things (ex.: dressing and grooming selves, going to school, having non-disabled friends). Again, in 2020, this is something readers are conscious of, so authors try to avoid it unless they are specifically parodying or satirizing the practice. For the BSC though, inspiration porn wasn’t a familiar concept. Treating people with disabilities as inspirational, or trying to make them “normal,” was actually the right and kind thing to do.

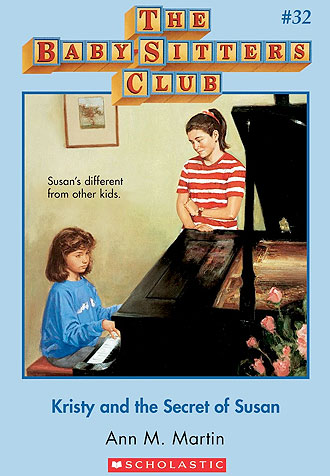

The original series is also fairly rife with ableism, or the privileging of non-disabled people over those with disabilities. Ableism is common among the BSC’s charges, in many ways. First, if a child with a disability is introduced, it is likely he or she is a one-off character, brought in to “teach” a BSC member a lesson in compassion. Two major examples are Susan Felder from Kristy and the Secret of Susan, and Matt Braddock from Jessi’s Secret Language. They are autistic and deaf, respectively. Granted, Matt’s arc and presence in Stoneybrook is handled a bit better than Susan’s, in that he is seen in other books and playing with other kids (all of whom are hearing; apparently, one kid can only have one disability at a time in Stoneybrook). However, the book featuring him is mostly about Jessi, not Matt, and how she needs to learn sign language to empathize with him and learn that deaf people are just like “regular” people. Since Jessi is also a minority, the whole thing smells like inspiration porn, or the practice of making disabled people, and sometimes other minorities, heroes for doing everyday things or having “normal” relationships.

Eight-year-old Susan Felder fares worse than Matt Braddock. Again, some of her troubles can be blamed on time frame; she’s an autistic character written in a time when autism was rarely if ever heard of in fiction. Certainly, most readers weren’t aware of inspiration porn and the heavy stigmatization of autism in particular. That said, Susan is quite the stereotype. She is a savant, able to play complex piano pieces after hearing them once, or give the day for any calendar date as far back as one wants to go. Beyond this however, autism is Susan’s defining trait. She does not talk except to sing. She stims, often playing or singing certain songs over and over. She will not respond to hugs, cuddles, or other positive stimuli and won’t ever make eye contact. In one scene, she goes to the bathroom on herself, in front of other children–because Kristy had practically yanked her outside to play, not noticing Susan’s silent signals that she had to go. Her parents’ solution to all this is to send Susan away to a boarding school for disabled children, and although they clearly love Susan, they often talk about how difficult she is to care for. In fact, Kristy learns Susan doesn’t so much as come home on school breaks, unless there is absolutely no other option. In other words, according to the Felders, Susan’s savant characteristics are her saving grace from being a totally unmanageable child, but they are not very useful.

Kristy becomes Susan’s able-bodied “savior” of sorts in Secret of Susan. She erroneously believes if she works hard enough, she can draw Susan out and get her to act like a “normal” kid. Of course, Kristy’s only thirteen, so we can somewhat forgive her. She does try to observe and understand disability more as a result of babysitting Susan, and she does try to protect Susan from being harassed. But at no point does Kristy fully realize that Susan or other disabled kids are valuable because of who they are. She observes students with disabilities at her school and feels mostly curiosity and pity toward them. Those students are segregated; Kristy only sees them at a school-wide assembly, and one is with a full-time adult aide. When an able-bodied student triggers hyperactivity from a boy with ADHD, Kristy only notes how disruptive the boy becomes. Throughout Secret of Susan, she maintains a sense of detachment from disability, except in terms of being compassionate toward people who cannot do what she does or are “other” than her. When she approaches the Felders to plead for Susan not to be sent away from Stoneybrook, they listen–but again, only because they see that some people can treat their autistic daughter with something other than curiosity or fear. Again, the fact that a thirteen-year-old, able-bodied babysitter is sticking up for this child also makes Kristy into an unnecessary and unrealistic “savior.”

“Glamorization” of Trauma

Finally, adult readers of The Baby-Sitters’ Club may find problems in how Ann M. Martin and her characters choose to handle trauma. Considering that, again, said trauma wasn’t often touched when the books were written, this is a lesser problem than the others we’ve discussed. Yet, it exists in the underpinnings of almost every book. This writer comes from a traditional nuclear family, and remembers her own parents constantly complaining that divorce was “glamorized” in the books. As a kid, she thought her parents were being ridiculous, but has since seen other readers and parents make this and similar complaints.

Divorce is a big offender here, although in 2020, it’s not necessarily because two-parent families are an ideal or possible for everybody. Rather, it’s because Kristy, Stacey, and Dawn, who have all experienced divorce, seem overall better off for it. This would be okay if the girls said things like, “Divorce sucks, but at least my parents don’t fight anymore”–and they do say that. But at the same time, Kristy gains a millionaire stepfather who constantly takes a bevy of thirteen-year-old girls on expensive trips, to the exclusion of his other children who don’t get to bring a cadre of their friends. Dawn and Mary Anne play matchmaker, rekindling an old romance between Mary Anne’s dad and Dawn’s mom, apparently forgetting divorce and death got them to that point. Stacey struggles with the divorce, especially when newly diagnosed diabetes causes new problems between her parents. But she still spends a lot of time going on expensive, glamorous trips to New York City, bragging about it, and unfavorably comparing Stoneybrook life. As for the newly blended families, they sometimes have small problems–Dawn declares Mary Anne a “wicked stepsister” for insulting her vegetarianism and not going along with her choice of haircut. But in general, the message is, blended families or “second” families are usually better than biological ones.

Death also gets the glamour treatment, if not the same way divorce does. That is, The Baby-Sitters’ Club is written for preteens, so whether we’re seeing a grandmother die, hearing of a long-dead parent, or seeing a pet put to sleep, we are not going to get the gory details. It’s also realistic to expect a deceased person or pet to be idealized in memory, which also happens. The glamour treatment usually comes from the aftermath of death. Again, Mary Anne might be the best example. She doesn’t remember her mother, who died when she was an infant, and that’s fine. What is not fine, is how little focus is given to honoring the mother’s memory. For instance, Mary Anne finds a “mother figure” in Claudia’s Grandma Mimi, only to lose her, too. In a later book, when Mary Anne finds out about the custody dispute between Dad and her maternal grandparents, she’s expected to be wholly sympathetic to her bereaved grandmother when the latter says cruel things about Dad. When she gains a stepmother in Sharon Schafer, she is of course thrilled to have a mom–but the biological mom largely fades into the background, more than she already had. At the same time, meeting Sharon makes Mary Anne’s father a lot less rigid, apparently overnight. The message, then, becomes that Mary Anne’s mom was at least somewhat replaceable. “Mother figures” are not acceptable versions of mothers. Stepparents “fix” broken families. This is, of course, an improvement over the usual “wicked stepmother” plot, but it feels too sweet and trite.

So, What Should the New BSC Look Like?

With so many issues in mind, readers understandably wonder if the BSC can charm the current generation as it did previous ones. Some say no, and determine to act as if this book series never existed. Others point out the dating of the original books, say the 2020 audience needs to loosen up, and largely ignore the problems.

So, which group is right? Neither–and both. On the one hand, there is no such thing as “politically correct history.” Authors were given different parameters and “rules” to write by in the ’80s and ’90s, and they didn’t have our concepts of diversity, trauma, and other issues. The original decades of the BSC were, for better or worse, “simpler times,” and there’s something to be said for respecting that. Leaving the original books and movie as they are, and not jumping in to retool everything, sends a strong message about our past. Specifically, where were we then, where are we now, and what have we learned? What did we get right, and what do we still need to improve upon?

On the other hand, it is hard not to look at the characters and plots of the original books without a twenty-first century mindset, and that’s okay, too. The retooling of some books into graphic novels speaks to our ability to move forward, as does the upcoming Netflix series. For one thing, the formerly white Dawn and Mary Anne will now be Latina and biracial, respectively. One episode is slated to feature a transgender child, and one divorce is said to happen when a parent left the closet. This will hopefully salve some old wounds among certain communities, and hopefully, more diversity and realism will follow. The fact that the Netflix series dares tackle controversy at all, let alone with these huge moves, is groundbreaking. It tells us while we can’t change the past, and maybe shouldn’t try, we can impact the present. Whether that’s for good or ill is up to who you ask; some new readers and viewers will likely love the changes while others will hate them, saying they’re a symptom of a society trying too hard to be “woke.” The final verdict remains to be seen. However, it is safe to say the old BSC and the new BSC can, with deft hands and insightful discussions, unite to create a club that welcomes and satisfies everyone on some level.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I can still picture the exact section of my primary school library where these books sat! I read quite a few and loved them. As with any media I happily consumed as a kid, I look at these books through rose-coloured glasses. So the points you make of how they are potentially problematic are really interesting and eye-opening to me. You definitely make some very valid points that I had never considered.

I think what I love most about this series, and any popular series targeted at preteens really, is that they encourage and inspire preteens to read, potentially more so than they usually would.

A great article, made me feel very nostalgic this Friday evening! 🙂

Awww thanks so much for the walk down memory lane!! Such a huge part of my childhood! Did you ever collect the hard cover books that had little trinkets in them and they were filled with letters and postcards that the girls wrote to each other?? I’ve got about 4 of them I think. And I loved collecting the mystery series and the summer special books which were always so much longer than the usual books and felt quite accomplished whenever I read them back when I was younger. Have been watching the new series and have to give Netflix credit where it’s due cos they have done it justice and has made me happy watching it! Love seeing some familiar faces of the parents and can’t believe I remember all the kids they used to baby sit for. So much fun!! Ok sorry for the long essay. 😀 I’m going now!! Great post!

I didn’t collect the hardbacks (because man, those things were expensive). But I did have several of the ’90s edition paperbacks, and I did check out hardbacks from my school library.

Did you like the new series of the baby sitters club? I did it was great, my fav baby sitters club members are Mary Anne and claudia they have been when I first started to like the series and I also like Karen from the baby sitters little sister series to,I find her very funny. 😉

I did like it, yes. I felt like some of the changes were pushing the “woke” agenda/mindset a little too hard (the camp two-parter is the biggest one, because of how the protests were handled and the girls were treated). But I think the writers, actresses, and others got a lot of things right and I’m looking forward to Season 2.

I loved it! They did a great job at making the series relatable for a new generation and nostalgia-filled for us OG readers. 🙂

When I was a child a teenage girl from my church introduced me to the series by giving me all her old books. I was probably too young to be reading them but I LOVED them.

Thankfully I still have all my books since my mom never let me get rid of books. I think I even have the postcard book too!

My childhood is all about BSC. I believe a huge chunk of my love for reading is because of it. I have never seen the show as it was never available here in the Philippines. And I can still clearly remember, I was around 13yo I saw the movie being advertised on a foreign channel and I was very excited but ended up being disappointed because the channel had a very bad reception and that was the only time I saw it on tv. I look back on that memory and it still makes me sad. Lol. Nostalgia is an understatement. I still have my OG BSC books with me and Im already 30.

I loved The Baby-Sitters Club. I also loved Sweet Valley Twins. Heh.

This brings back so many memories. i had the complete guide book when i was a kid.

Can this 66-year-old man watch the Netflix series with his 10-year-old grand-niece?

I don’t see why not. She’d probably love that.

I absolutely loved slightly vintage, well written, English style American tween books when I was growing up, especially the Babysitters Club, Sweet Valley High, all the different ‘Point’ books, Judy Blume, the Sweet Dreams series (which were my ultimate favourite). I actually now really regret hiding in my Nana’s pantry to search for the rude bits in her Jackie Collins library books at far too an early age, destroying that early innocence.

Flashback! Loved The Baby-Sitters Club.

We used to play Baby-sitters club in my primary school playground. That and Thundercats. Ah the memories….

Watched the first three episodes with my 12 year old daughter and was saddened to see how the girls appear to have wardrobes most young teenagers could never afford to match. The opulence of the girls’ lives, the houses of delightful leafy suburbia, the size of their bedrooms, their parents cars, all paint a very subjective portrait of American middle class bliss, promoting the very worst of the consumer society. I would hate to see my daughter emulating these characters.

And that is a valid point. I think the fictional suburban Stoneybrook gave Ann M. Martin and her characters more freedom in topics they could explore, because there wasn’t as much pressure to get a real place “right.” But I can see how the current Netflix series would be improved if, say, the girls were from different neighborhoods within Stoneybrook or, failing that, at least had socioeconomically diverse backgrounds or experiences.

From what I understand after reading this article, The Baby-Sitters Club did the best it could handling hard topics and diversity. However, it could have maybe benefited from having a person of colour or a couple people (including those of colour, from minorities, etc.) writing the series to make it more realistic and balanced. When you’re not used to experiencing the issues discussed in a series like this, chance are you’re not going to get it right, no matter how hard you try.

True. I’m a writer too, so I try to give authors a wide berth as far as how well they write diverse experiences. Unless they’re completely clueless, writers do try hard. But as you said, that’s why you would probably need a team of different writers working on books like the BSC. Perhaps if a black author could’ve written Jessi’s books, a Japanese author could’ve written Claudia’s, and so forth?

I love your conclusion. Most people don’t write very good ones.

Thanks. You can give credit to some diligent English teachers. 🙂

Just want to point out that Travis (in Dawn and the Older Boy) was 16, thankfully not 21. That would have been a while different story!!

Great article, though! I think the series is more classic than problematic, and I think a lot of the problems stem from the time it was written. Reading them as an adult in 2020 is much different than reading them as a tween in the early 90s.

Yes, it’s MUCH different. And thanks for the correction. That’s one of several I didn’t read, and all the summaries I found said he was 21, so…but, thanks anyway.

Aw I loved these books!

Loved the books. The Netflix adaptation sounds like it’s too woke to be respectful to the original. The whole point of BSC was it was wholesome, innocent, wide eyed & not beholden to any agenda at all. Sad, but Netflix really do like to throw in a lot of woke curveballs to their product.

Describe to me the difference between wholesome/innocent and woke ..?

The original series was woke. Evident when reading this article (good job). It dealt with racism in several books. When a black family moves into town they aren’t welcomed by a red wagon like other families so the girls throw them a party and she joins the club. Nostalgic doesn’t equal racist for everyone just actual racists.

Wow. I must have hoovered downs dozens and dozens of these books from my local library when I was a kid. The library used to be down the road from where I lived (it’s now an open space after the council demolished it and replaced it with nothing). There was also a Baby-sitters Club TV series made in the 90s(?) that I remember watching sometimes on Channel 4 very early on Sunday mornings. Nice to see it back.

I loved the 90s TV version! Best theme tune ever! And there was also a film that was less good…..

Yay, The Baby-Sitters Club! I’ve been a fan since I was about 10 (now 24),and I have the strongest memories based around the character Dawn. Simply for the fact that we share the same name. I was introduced to the books via a local book sale. Unfortunately, being an idiot,I sold a few of my original books from my childhood at a yard sale a few years ago. So, I’ve been trying to compile my collection once again.

I LOVED the original Babysitters Club books as a tween! Point Horrors and Sweet Valley High too…

Omg the nostalgia! I used to love the mystery series- and of course I had the Shannon book. I got a bunch of the Little Sister books via hand me downs but I don’t think I ever read them. I LOVED the California Diaries though- I want to re read them as an adult. Great article!

Amazing piece. I ‘inherited’ the first 50 or 60 books from my big sister’s best friend when I was a kid in the early 90s and kept collecting and reading them from there. I’ll have to put a list together of what I’m missing to add to my thrifting wishlist.

I’ve been on a BSC binge all evening… so glad I came across your article! Wish I still had all of my books. Love your writing.

I’m 1987 so thank you for this nostalgia service. I still sing the tv show theme, and have 2 tapes, including the Christmas one I use as decoration during the holiday.

This is the most amazing thing ever! I know no one who remembers/still loves the Babysitter’s Club! Such nostalgia… I recently found the BSC necklace at a craft show for $1! I freaked.

This is awesome! I was a HUGE fan of the Little Sister series – maybe because my parents divorced and I have both a stepmother and father as well? I remember there being SO MANY books in the series, though. I couldn’t keep up! And the storylines kept getting more and more outlandish. I keep hoping to find some books at second-hand shops, but I’ve never come across any. I used to own the first 20 or 30. Not sure what happened to them…

Here in Italy, they published only until book number 72… I loved each book, they where my childhood! Can’t wait to see the new tv show on Netflix.

I read a couple of the books growing up in the 90s and owned the Chain Letters book. I remember having fun flipping through the different letters and postcards. Being a California native, Dawn was my favorite babysitter.

I’ve read 1-66, as that’s what was translated into Dutch. I’ve read the first.. 12ish? Mystery and the first few Super Specials, and the first 2 Logan specials (not sure if there are more or not). The BSC game is complicated though. I’d love to see more of the TV show. I have one VHS tape with 2 episodes. My parents only allowed me to buy one tape, and by the time I had saved up more pocket money, I didn’t see the VHS tapes for sale anywhere anymore.

There is a BSC book with the kids doing a magic show which is my favorite! I can’t remember which one, but I have read it. I have seen the movie back in the day when it was showing on TV here. I recorded it off TV on VHS but unfortunately I lost the VHS tape.

BSC taught me a lot!

We have the same pictures on the Dutch covers, but the base colour of the covers and spines are different. I bought some of the BSC books I don’t have (because they weren’t translated) in English on my Kindle. However they do cost a bit for how long it takes to read them. On my latest re-read of the series a few years ago, I stopped just before book 55, because things were getting a bit repetitive. I hope to go back to it again at some point. Also, a lot of the names were changed into more Dutch sounding names, so it can be hard trying to relate the English to the Dutch books.

So much nostalgia and childhood memories in one article. I read them all in the early to mid 90s, up until I was about 12 or so. I had around 100 of the books, and a few of the specials, and I did have the movie on VHS, too. I never even knew there was a TV show when I was a kid, so I only saw the movie. Stacey and Mary Anne were my favourites, I think. I think I liked Mary Anne because she was shy (and I was terribly shy as a child). I think I even had my hair cut like the actress who played Mary Anne in the movie! I have started collecting some of these books again recently, with the intention of re-reading them some day.

Yup, Mary Anne was a favorite of mine, too. But I think Mallory became my absolute favorite because we were both writers. Jessi was a close second/third, because although my body wouldn’t let me do ballet, I very much appreciated the art.

The Baby Sitter’s Club was SUCH a huge part of my childhood. Every time we’d get a scholastic book order I’d have a huge stack of books and I’m sure there was at least one BSC book in the mix every time.

Claudia and Mean Janine was one of my favourites when I was a kid.

I read babysitters for a little bit and it’s such an important series in my mind as it was one of the very first books I read when I started becoming a reader. I loved the deep analysis.

It sounds like they’re definitely meant to be able to be read individually despite it being a “series”.

Yup. You can start anywhere in the series and feel “caught up.” The fact that the characters are introduced in each book definitely helps. Now, as a 30-something writer, that drives me nuts because it’s an info-dump. But in fairness, it works for the kind of series the BSC is, and the demographic of the readers.

I bet you I am the only 42 year old male in the world who owns all of the Baby-Sitters Club books.

That might be a safe bet, but just in case… 🙂 I’m pleased to see males enjoyed the books, too. I don’t know if this was everybody’s experience, but when I was a kid, it felt like books were very “gendered.”

Possibly, but for what it’s worth I just turned 39 and also male.

Never did get the books, but I watched the original show in the 90s on the Disney Channel.

Checked out the Graphic Novels from the library and eventually getting my own copies (BSC and the comic adaptation of Little Sister).

Also saw and enjoy the Netflix show.

This is my childhood. Right here. I wish I had some of this extra stuff like the dolls and the games and VHS tapes. I’ve only ever collected the books and I’m missing secret santa still. Does it count that I have all the little sister books though? I’ve been a fan of the books since I was maybe 8 and I’m turning 26 this year and now I’m remembering them because of the TV series.

This brings back so many memories! I felt like I was the only girl who loved the Baby-Sitters Club growing up. I had most of the collection and I LOVED the mystery series! I also had the board games which were fun and I remember when they showed the tv show on the Disney Channel for a short time. I wish I still had all my books. I’m so sad whenever I think about my own collection as a kid and how much it would’ve meant to me today if I kept them. At least now I have an article like this to reminisce of the good times when reading was so much more fun than anything else!

I’ve been wishing for a long time they’d put the older show on DVD. Even my husband watched the show when it originally aired on TV. He had a crush on Claudia.

Being in my 60s, my passion is Nancy Drew books. I’ve got the original blue and yellow ones, and some of the paperbacks.

I had some of the original blue and yellows, too, and some of the later paperbacks. I think my favorites were Mystery of the Ivory Charm (#13), and Clue of the Whistling Bagpipes (the number escapes me). In other words, I loved when Nancy solved mysteries with a foreign country component.

This was so nostalgic! I certainly remember reading the BSC books as a kid, but I must not have read that many… My favorite book by Ann M. Martin was Missing Since Monday.

I used to have the Claudia doll. Thanks for the blast from the past! Shared it with my childhood friends.

I’ve always wanted to read the Baby-sitters Club series but I didn’t know how many books are out there. Well, now I know and I can start trying to find them in thrift stores so I can read them!

My older sister had soooo many baby sitters club books! but i guess being much younger i preferred the little sisters books

I just loved these books when I was a kid. I had all of them.

I remember reading these as a kid. Though the girls seemed to remain at age 13 forever.

A good essay. I remember two of my daughters reading several of the books in this series.

Definitely getting 80s vibes from the Babysitters Club.

How could you not? The hair alone… 🙂

When I think of something being ‘problematic’ I tend to think of that as meaning something that encourages or normalizes behavior or beliefs that are dangerous or unacceptable. I think having a “cult” of you and your friends is a fairly minor concern in the long run

That’s a good way to look at “problematic,” because it’s a buzzword I think gets overused. I never thought the BSC was cultish when I was growing up. Actually, I wished I had friends that close. However, in an attempt to be objective, I can see detractors’ points of view. There are situations in which the girls don’t treat each other well, and while that’s realistic, it happens enough within an insular group that I can understand where “cult” comes from. I think if I were reading the series with a niece or daughter today, I would ask her what she thought. And then we might talk about “close” vs. “maybe too close.”

I totally agree with what you said about no such thing as a politically correct history. Just because a work of fiction has blind spots in its approach to groups or issues-obvious or implicit biases, a lack of equanimity in how compassion is extended, and the way that certain characters are utilised-doesn’t mean that we should shield future generations from them. If it weren’t for modern writers being aware of the problems you’ve described with BSC, we most likely would not have had the attempts at inclusion and diversity that are reported to be in the upcoming Netflix show. Still, I suppose we can’t let nostalgia blind us to those faults in works from the past either. It’s good to ask questions.

PS This article makes me want to check out The Babysitter’s Club as 21-year-old zoomer. Maybe I’ll track down the movie or one of the graphic novels sometime 🙂

I’d recommend the older novels (non-graphic) if you can find them. Nothing wrong with graphic novels, but I personally find the format distracting at times. Then again, I didn’t grow up with it. The movie was one of my favorites as a kid. Not so much now, but it’s worth a watch.

What about Whitney the girl with Downs Syndrome who Dawn was “friends” with while she was in California? Of course her parents paid Dawn to babysit her under the guise of friendship.

Oh, egads! I completely forgot about that one! I remember even as a kid thinking, “Okay, NOT reading that one” (it was previewed in another book). And you’re right. There’s a whole host of problems with that book. Not only the ones I mentioned in terms of disability in general, but:

(1. The implications that people with disabilities can have non-disabled friends only in a “caregiver” context/not really friends

(2. The PWDs are too dumb or innocent to know the difference, until it becomes obvious or somebody slips and says something

(3. If the PWD gets upset, they have no right to be, because at least that person was kind to them/”being a friend”

(4. Just the implication that the parent of a child with a disability would do something like what Whitney’s parents did. It shows they don’t believe in their child, and that they think she’s so “other,” she can’t possibly do what others do or have what others have.

Again, egads.

Even if Whitney became an honorary member of the We ❤️ Kids Club it is still problematic

Absolutely!

As a disabled person who read these books, the treatment off disabled characters in these always made me uncomfortable.

Great discussion as always. I too loved this series. A really good look at some key issues that are present. I agree the cult idea is a bit exaggerated, anyone in that age knows how cult-like cliques are anyway, but the discussion of ableism is really good to consider. Thanks for putting this out there.