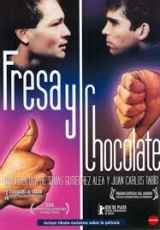

The Construct of a True Revolutionary in “Fresa y Chocolate”

Fresa y Chocolate takes up the controversy of determining the role of the intellectual in the Cuban Revolution during the seventies and eighties. Set in 1979, the film depicts the journeys of Diego and David, two very different individuals, but each a revolutionary in his own right, on their path of revolution. Diego, a homosexual man, appears to be everything counter to the cause of the Revolution: he is a man that gains freedom through spiritual, sexual, artistic and personally achieved means. Since Diego is already outcast within the framework of the Revolution because he is a homosexual, he is able to truly embody the truly revolutionary by his willingness to take more risks.

David, on the other hand, embodies everything capital-r Revolutionary, an important distinction to make from using the term to describe Diego. David is a child of the reformed education system under Fidel Castro and knowledgeable in everything that constructs the new Cuba. He is very two-dimensional, however, because he seems only to be able to think in terms of what he has been fed through the doctrine of the Revolution. David’s freedom is regulated by the government. Through the foiling of David and Diego’s conceptions of literature and rhetoric within Cuban culture, the film posits the idea that Diego is the more revolutionary of the two men for his willingness to break with conformity for the sake of true freedom – whether it is intellectual, sexual, spiritual, and political.

From the beginning of the film, sex is established as an integral part of the framework of society, and almost a determining factor in one’s role in society. David states in the beginning of the film that everyone is preoccupied with sex. Vivian wants sex and love to be the foundation of setting her up for a good life; Nancy is a labeled a whore from early on in the movie; Diego openly celebrates his sexuality; David is a virgin who comes to his sexual awakening with Nancy. David gets his happy ending, but Diego has to leave his country in order to hopefully find his bliss.

David is the prime example of what it means to be a Revolutionary in Cuba. He studies political science rather than literature which is his true passion. David tells Diego that the reason for this is that political science scholarship is what the Revolution needs most, and David must do his part to contribute to the collective. He is learned in rhetoric, but it is a limited one that comes from a skewed perspective given by a university setting working to create minds that uphold the Revolution’s themes in Cuba. David, the hetero-normative male, is an upstanding student of the Revolution; whereas Diego is outcast for his open homosexuality.

What David discovers, however, is that Diego is far more intellectual and revolutionary than he ever thought possible. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word revolution as “the action or an act of moving in a circular course or around some point; a completed cycle of motion of this kind, a circuit.” Fresa y Chocolate posits this point as Diego, the embodiment of culture and identity that is being subdued by the Revolution. Diego defines cultured in terms outside of Cuba and the Revolution. He is learned in opera and classical music; he is a scholar in European literature and poetry; he openly celebrates the Cuban cultural greats that have been rejected by the Revolution such as José Lezama Lima; behind closed doors with loud music playing he speaks freely about politics and the state of his country. Diego is already outcast in society because of his sexuality, his love of the high arts, and his beliefs. Because of this it seems that he is willing to take more risks – from actual in depth discussions of politics behind closed doors with loud music playing to controversial art that isn’t a part of what creates Cuba.

Rather than defying the freedom gained in the Revolution, Diego embodies a different sort of freedom – a freedom to learn and to express one’s self in every way possible. Diego lacks a certain subtlety that goes hand in hand with the new order in Cuba and holds nothing back. He openly flaunts his sexuality, his high cultured learning, and his appreciation for ‘highbrow’ literature and art. Diego speaks his mind – even to the detriment of his own character – often making racist and classist comments when criticizing society behind closed doors. He is truly free in that he speaks his conscience for the good of society, and not society as solely dictated by the Revolution. Diego believes in a Cuba that celebrates all of its history and influences, not just those that advance the ideals of the Revolution.

Diego often cites José Lezama Lima and John Donne’s poetry as existing among the greatest literary minds in the world. Lezama Lima seems to be Diego’s greatest role model as the essence of what is truly Cuban, even though his work is not widely accepted within the Revolution-sanctioned literary canon. Donne, an English metaphysical poet, is another writer that no longer finds a home within the isolationist dynamic of Cuban teachings of literature. Themes within Donne’s poetry pit the sexual and the religious against each other within the Renaissance, much like Diego himself is a contradiction of the sexual, religious, and intellectual free thinker. Metaphysical poetry makes comparisons that one would not be quick to generalize in order to create a reform in the thinking of the religious body. Diego himself is an example of this revolutionary rhetoric in action.

The dialectics within the film are presented in the framework of strawberry and chocolate: Diego and David, the artist and the child of the Revolution, art and intellectualism for the good of the Revolution. The problems seem to arise from the inability to mesh these polarizations because it seems that within the Revolution certain kinds of art are allowed to be appreciated in secret. Or if they are allowed, it is only under the right circumstances and specific instances.

David enjoys writing literature and brings some of his work for Diego to read, but Diego cannot stomach the saturation of Revolutionary themes in the work. David tries to place portraits of Che Guevara on Diego’s wall of the artistic greats that contribute to Cuban identity, but it strikes a dissonant chord among artists like Maria Callas and Lezama Lima that embody a spirit of Cuba gone by. David, the more “Revolutionary” of the two men, is two-dimensional in his limited learning; Diego is free to create his own worldview of what is truly Cuban and free. It seems as though the ability to be a free spirit is not something that exists under the banner of Revolution.

Through the foiling of these characters’ ideals Fresa y Chocolate shows that, within the eyes of the Revolution, non-intellectuals are caught up in the baser pleasures of art and sex, while the true intellectual tries to rise above and focus more on matters of rhetoric for the good of the Revolution. The film suggests that Diego is the most revolutionary because he is the most truly free-thinking person, but the film, however, seems to implicitly suggest a need for the coming together of the baser pleasures with the higher pleasures of learning. This combination is posed as the way to make a true utopian society evidenced by the growth of David and Diego to true friendship and understanding each other. The possibility of this actually being able to be achieved within the Revolution, however, seems unlikely at best. The film posits the need for the balance between free thinking and collectivism within the Revolution as the keys to best succeeding for the good of all, but does not make it seem as though it would ever happen.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I remember the first time I watched this film, as if it’s yesterday. I totally loved it and watched it again when it came on cable.

Watched this on its premiere! I thoroughly enjoyed this movie! I spend a majority of each semester attending foreign films. And while some are painfully dull or poorly made, I never fail to view a movie that I want to directly go out and purchase and watch again and again on my own time. This was a fine example.

It manages to be charming and delightful, even in an environment which is restrictive and bleak. And it stands out among its genre as a movie worth remembering!

This is a very good movie. But I think the director’s best movie is Memories of Underdevelopment (1968) It is a very complex movie. Outstanding.

Cuba, as many Cubans like to say, is a complicated country. There is an enormous amount of false propaganda from both the Cuban and U.S. governments, and it wouldn’t be wise to accept either as fact. In other words, don’t believe everything you’ve been told about Cuba, as much of it originates from the right-wing U.S. media which portrays everything in black and white. The reality is much more complex.

For one thing, views on homosexuality in Cuba, like in many countries, have evolved. The public persecution of homosexuals has declined sharply. Just recently, the highest-rated show on Cuba’s state-run television was a soap opera in which a married man fell in love with another man. And now this country is on the verge of enacting a law that gives same-sex couples some form of legal status. One of the leading advocates of gay rights in Cuba is Mariela Castro, daughter of Raul Castro. This certainly doesn’t mean that Cuba is a gay haven, but things are changing. The U.S., meanwhile, is one of the most backward countries in the developed world when it comes to gay rights, and even trails a number of developing countries in this regard.

This is one of my favourite foreign films, in the top 10.

The whole atmosphere of the films totally draws me in. The complex issues surrounding the characters, the story line, the meaning. It really made me think. And I like movies that do that.

It’s pretentious strange crap if you ask me.

I thought it was brilliant. Not too many ppl are going to go for political propoganda as far as Cuba’s concerned, but I thought it was hilarious. I caught in on cable years ago; I want to re-watch it again, so I’m ordering through Netflix.

This film is anything but pretentious, quite the opposite… it roots for the underdog, so to speak. Perhaps it’s necessary to understand the cultural context to fully appreciate the many layers of messages Alea is trying to convey.

Insightful analyses!

this movie was the only movie in cuba (that year) to recieve government funding..and civil unios for same sex couple are being discussed and the government is backing them…there has being a change in cuba towards gays..

Helen thank you for the wonderful article. I will have to add this to my list of Cuban Revolutionary Films. I have two that are similar to what you are speaking of in this article:

Motorcycle Diaries (2004) with Gael Garcia Bernal, a story about Che Guevara and his contribution to the revolution.

Before Night Falls (2000) Javier Bardem and Johnny Depp, a film about homosexuality and art in Cuba.

I would be willing to watch this movie. It sounds very dense in nature though, so it might require multiple views.

This does show that certain types of revolutions look awfully close-minded once they take control.

The Cuban revolution has gone on to prove the ending statement of this review wrong. Revolutionary Cuba now leads the world for LGBT rights. One only need look at their new family code.