Life’s Torments in Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend

Life is addiction. Life as addiction. Cinema as reality. Billy Wilder’s sensibilities are stretched to the maximum in The Lost Weekend, a tormenting roller coaster of a story that brings to the fore human darkness as much as any Hitchcock film, if not more. There’s a reason why Miklós Rózsa’s theremin is so well interconnected to both this film and Hitchcock’s Spellbound, both released the same year – 1945. The haunting theremin wail perfectly encapsulates the torments of the mind, the anguish of the soul and the dark intentions we always fall prey to. Can it be a coincidence that both films were released at the end of a long and tormenting world war, a war that made the word “human” almost lose its meaning? For Billy Wilder, writer-director of The Lost Weekend, it was especially painful, as he lost his family in Nazi concentration camps.

Billy Wilder is to many known for his almost perfect comedies (The Apartment, Some Like It Hot) and noir dramas (Double Indemnity, Sunset Boulevard). The ease with which he switched gears from comedy to drama epitomises Wilder’s special philosophy of life. He shows us that we can make light of a terrible situation, but that we can also find darkness lurking behind the appearance of normality. In The Lost Weekend, he manages to present alcohol addiction in all its gritty, unholy reality to the point where the alcohol industry offered the studio $5 million not to release the film. Wilder later joked that if he’d been personally approached with such an offer, he would have accepted it. I’d like to think that behind the joke there was the confidence in the strength of this production as well as the belief that such a controversial film, especially one dealing with alcoholism during the Production Code, would capture the audience attention. He went as far as to successfully predict Ray Milland winning an Oscar for his performance, so the confidence was well deserved.

The Lost Weekend is a film in which very little happens on the surface, but in which even walking down the street can become a torturous affair. Alcoholic Don Birnam successfully plots not to go on the weekend trip his brother had planned for him, choosing to try and drink himself to death. But, just like there’s two aspects of life, the light and the darkness, there’s two of Don: the writer and the drunk. Moreover, there’s two people who love him. His brother Wick loves him out of duty and perhaps pity, but he doesn’t trust him, and he will not go all the way to save him. His girlfriend, Helen loves him with abandonment, passion, and almost religious devotion. She will go all the way. Don’s is a story of addiction, redemption, and hope. Hope as embodied by Helen. She’s the face of a resilient love.

Billy Wilder’s direction goes beyond the usual admirable technique. His camera remains unobtrusive, but ever perceptive, projecting Don’s tormented mind in dizzying fashion, complementing Miklós Rózsa’s obsessive score in a perfect harmony of pain and despair. This is film noir territory; a style Wilder had just cut his teeth on in Double Indemnity a year earlier. Most of the film is in shadow, thus emphasising the darkness that lurks beneath Don’s eyes. The bottle is there, present from the first scene. The camera pans and… there it is, hanging outside Don’s bedroom window! Wilder cleverly manages to show the audience what Don is thinking without much effort and with no dialogue. As the camera remains outside the window, as we see the piece of string hanging, we don’t even need to see the bottle to know it’s there. With a nervous glance over his shoulder towards the open window, Don is seen packing. The audience thus knows, feels that, with his back hunched in an already confessed but unuttered sin, Don is thinking about the bottle hanging outside his open window. He is packing but his actions are uneasy, like those of someone not entirely there. The nervous glance over his shoulder confirms it. The audience will later find out, in a scene that perfectly bookends this first scene, that all Don was thinking of while packing his suitcase for a long weekend in the countryside, was how to find a way to get his hands on that bottle, how to be left alone with it.

Left alone with it he manages to be. He ushers Helen off to a concert with his brother Wick. He then steals the housekeeper’s money from where the brother had left it, and goes off to buy two bottles of rye, stopping on his way home at his local bar. A seminal scene defining Don’s character comes right after he’s bought the two bottles of alcohol. The clerk had put them in a brown paper bag that was too small. So, Don felt he had to buy three apples from the greengrocer’s so he can put them around the bottle necks sticking out from the paper bag. He didn’t want to be seen walking down the street carrying two bottles of rye. He cares about his image enough to conceal his alcohol from people on the street, which include his own landlady.

Earlier, when he’s talking through the door with the housekeeper, as he lies to her about the money Wick has left her, he’s holding the $10 note behind his back, despite the fact that the housekeeper can’t see him through the door. Don acts riddled with shame throughout the film, pain on top of which all the other pains and obsessive thoughts are placed. There’s little wonder, then, why Don’s cowering and walking all hunched. He carries the weight of the world on his shoulders. At the same time, the sinful glee with which he glances at the glasses and bottles of alcohol when they are in his sight is but a temporary respite. He’s expecting a different result from every “binge, bender, spree” he’s been on, yet he’s not changed his tactics.

When he goes to his local, Nat’s Bar, he orders a glass of rye, his eyes sparkling with desire for the drink, tongue smacking his lips in anticipation, beads of sweat adorning his face, now almost distorted with the pain of want, as he holds the glass full to the brim, ready to down its content in one quick, thirsty motion. He needs it. He feels in in his whole body, the need for the sweet amber liquid. And then he stops. He puts the glass down. He looks at Nat and composes himself. He’s not that sort of drinker. He can take it or leave it. He lights a cigarette, all nonchalant. Except that he is that sort of drinker! Image be damned, he will drink this glass straight up, because he cannot wait one more second. The theremin wailing accompanies this important scene. Soon the violins and brass music accompany the theremin. As the music swells up, the audience understands the battle that’s taking place in Don’s head. He downs the drink as if his life depended on it. It is the first scene in which we see Don drinking. We know it’s been ten days since his last binge. And the ten days are ended in a blink of an eye, in one quick hand motion, in one quick upward jerk of the head.

As he holds the empty tumbler, Don’s head tilts forwards, his shoulders close to his ears. He looks hunched over the bar, staring at the circle left by the glass on the bar’s surface. “Don’t wipe it away, Nat. Let me have my vicious circle” he says with an almost unbearable sadness. The sadness is accompanied by pride too. Don’s only certainty now is how the drink is making him feel. The vicious circle is a known quantity. He knows where he’ll end up. He can anticipate the shame, the disappointment. He can live with it, because he’s experienced it before. What he cannot fathom is the unknown. And so, he retreats into the comfortable clutches of alcoholism time after time, because it’s not a new experience, thus not generating fear. Don’s fear of failure, fear of being perceived as a failure paralyses him to the point where he’s made sure to be a failure. Alienating all those around him has become his favourite side-effect.

As the drinking spirals out of control, the theremin music marks the sinister development of the situation. Instead of being at home, packing for the weekend and waiting for Wick and Helen’s return, Don drinks glass after glass at Nat’s, each emptied glass leaving a circle on the surface of the bar. Despite it being a disheartening scene, Wilder manages to add a touch of humour to it, through Nat the bartender: “Say, why don’t you lay off the stuff?” says he, whilst pouring Don yet another shot full to the brim, leaving yet another sticky circle on the bar top. The bartender cannot stop him from drinking, as long as he’s got money to pay for it. The fun is superficial. The haunting music takes its place. Also, Don’s face, transformed by alcohol into a dark sweaty mess. Multiple rye circles later, Don is barely able to get back home, but lucid enough to hide away from Wick and Helen as they emerge disappointed and worried from Don and Wick’s flat. Wick has decided to continue with his original plan for the weekend, despite Don’s disappearance. Helen, on the other hand, will not give up. She waits for Don to return, unaware that Don’s sneaked back into the flat whilst she waited outside for him.

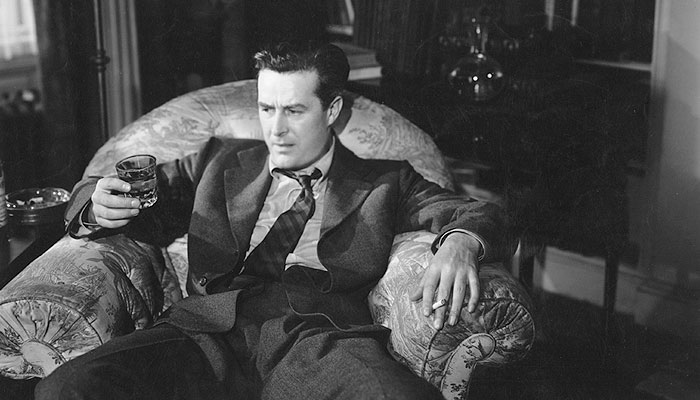

Wilder’s brilliance as a director shines through in a most haunting way. As he sneaks back into his flat, silently and without turning the light on (because Helen is still waiting outside), Don takes one of the two bottles of rye and hides it in the ceiling light fixture, knowing he would need it later. The scene borrows many elements from film noir, as Wilder has Don move around the house like a thief in the darkness, stealthily looking for the best hiding place for his beloved bottle. The music starts off as unobtrusive as he proceeds to hide his secret stash. The other bottle will be consumed imminently and with gusto. Don pours himself a drink and the theremin takes over, enveloping the room in a mournful song of despair which also provides the viewer with a dizzying sound that helps explain Don’s state of mind. The music perfectly complements Don’s face. After happily pouring his drink, he doesn’t drink it straight away. He puts the bottle on the table, next to the glass and sits on the armchair next to the table, with a blissful yet utterly terrifying grin on his face. The camera stays on his face for another moment, a chilling moment that encapsulates both the agony and the ecstasy of alcoholism, then pans slowly towards the full glass, closer, ever closer, until we’re swimming in its liquid and complete darkness sets in.

The darkness thus takes over the story. As each scene progresses, we see Don lose complete touch with the reality, dropping all his defences, disregarding his image, only one thought remaining in his head: he must get more alcohol. He steals a purse in a speakeasy because he can’t afford to pay for all the drinks he’s had, attempts to pawn his own typewriter, gets locked up in the hospital (alcoholics wards), escapes by stealing a doctor’s coat, and is ready to do it all over again until the resources run dry once more and Delirium Tremens sets in.

It is a battle of the wills between Don the drunk and Don the writer, in which nobody is able to win. This battle is projected onto his hallucinations, during his Delirium Tremens stage. He sees a mouse emerge from a crack in the wall of his apartment. Shortly after, a bat comes out of nowhere, attacks and kills the mouse in quite a graphic blood-splattering scene. It is perhaps no coincidence that the bat and the mouse are somewhat similar in appearance, the bat sometimes being called a mouse with wings, or bald mouse (chauve-souris in French). It is the bat who emerges victorious, just as Don the writer will emerge victorious from his nightmarish situation. He will find his bat wings, fly over and kill the lesser Don. But he will need all the help he can get to fight his addiction and his insecurities. The bat wings acquired are all the more appropriate, since Don is learning to navigate through a world of darkness. He will be able to see and fly through it, but he needs to get his wings first.

Ray Milland’s face is as haunting as the wailing sound of the theremin. When a glass of fun becomes anchored, heavy want, when want becomes need, a needy sweaty thirst without which walking and breathing becomes unbearable, then the darkness of the addictive spirit takes hold, grabs tights and doesn’t let go until it is perhaps too late. Milland’s face shows the haunted and haunting quality of both physical and psychological torment that comes with addiction and withdrawal. Miklós Rózsa’s score adds another layer to the torment, plunging the knife of lack of will deep into the wound of self-doubt.

Self-doubt is a relatable feeling. An earlier scene, told in flashback, in which Don is set to meet Helen’s parents, has the overarching heaviness of the theremin, announcing Don’s insecurities just as they are uttered by Helen’s parents. They don’t know that he’s hearing them and that their words echo his fears exactly. It is enough to drive him away, convinced he’s not good enough, making sure he won’t be good enough as he proceeds to go on a drinking binge instead of facing the judgemental looks of his potential in-laws.

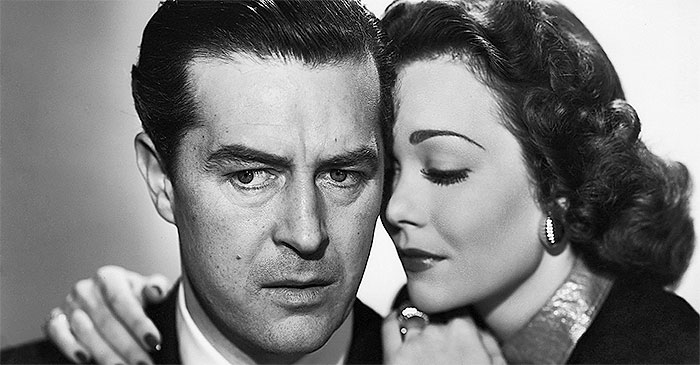

Helen, however, believes in him. She’s one of those rare creatures who believes in people when people don’t believe in themselves. In a poignant scene, right after the failed attempt to get Don to meet her parents, Helen finally learns the truth about Don’s addiction. “So, I’ve got a rival” she says, almost defiantly. She invites the challenge, her youthful resilience almost ringing true and hopeful. A beautiful and beautifully sad line, repeated in the film, has her almost whispering to Don “bend down” so she can give him a proper kiss. The difference in height is important in the two characters as it highlights a comparative different in spiritual hights. Don is taller, but he’s the weak one. Helen may be the short one, but she’s the strong one. She’s Don’s pillar, his only ray of hope. As he confesses the truth about his alcoholism, Don also urges Helen to leave him and find a better life for herself. Only she retorts with a defiant “You don’t know me.” As if to say, “do your worst, you’ll still find me here believing in you at the end of the day.” And she is true to her word. Don’s shame during his confession is expressed by his constant clutching at the glass of rye. Helen tells him to bend over so she can kiss him, thus showing him she loves him in spite of his addiction. Instead, Don, defiant and stupid, lifts his glass and downs the drink, in a pityingly bid for self-sacrifice. He wants her to leave him, save herself, move on, although he wants her. The want for her is not as strong as the want for alcohol.

However, Helen is twice as brave and three times as defiant as Don. Seeing as he won’t bend down to let her kiss him, she wipes his lips clean of alcohol, rises on her tippy toes and gives him a passionate kiss. She’s ready for the challenge. She won’t hear of any sob cases of “I don’t have what it takes.” She’s a successful woman working for the Times magazine. She’s successful and yet she loves him. She’s showing the audience that this is not a man without hope. This is a man who has a lot to offer, if we’re patient enough. It’s the only commendation we have. We’re not told what the brother does, the one who’s been supporting Don financially for the last few years. It doesn’t matter, because he’s not ready to go all the way with Don. After one too many relapses he’s thrown in the towel and has admitted defeat. Not Helen. Her resilience is admirable. She is the one with enough foresight to compare Don’s addiction to heart or lung disease, acknowledging that it is a force beyond Don’s control and that he needs her support. She will wipe this dark part of his life clean the way she’s succeeded in wiping his lips clean of the sickening substance. She will rise to the occasion. She will go beyond meeting Don halfway and save him. The Lost Weekend may be a story about addiction, but it is also a story about resilience and the importance of having someone one can rely on, someone who still believes in you when you’ve stopped believing in yourself.

As with most Billy Wilder films, there is light and hope in a sea of darkness. His philosophy of life is brilliantly expressed at the end, when Ray Milland’s face lights up as he talks about his future novel as if it were a fait accompli. He has a gaiety never before seen, not even when he was joyously, lovingly looking at his bottles of rye. The spark of hope is enough to light the fire of transformation. As she watches Don extinguish his cigarette in the unfinished glass of whiskey, Helen gives a sigh of relief. She is empowered once again to trust and support her man.

It feels almost like a miracle that a film so honest about alcoholism should be made during the Production Code era, an era known for its strict censorship policies with regards to vice. Paramount studio took a gamble, both with the censors and the audience. They banked on the Billy Wilder/Charles Brackett team and their previous successes. The gamble paid off, despite disastrous preview screenings and threats of boycott from temperance groups. Despite all odds, the film was a great success at the box office. It also won 4 major Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Actor in a Leading Role, Best Director and Best Screenplay. Billy Wilder was the first to win a Best Director and Best Screenplay in the same night, the latter shared with Charles Brackett.

Billy Wilder’s philosophy of life has resonated with audiences ever since, making The Lost Weekend one of the most heartbreaking, honest and haunting films made during the Golden Age of Hollywood.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Great analysis. I do remember the relentlessly grim, often depressing film The Lost Weekend. Yes, it’s excellent, and Ray Milland did an exceptional job portraying a drunk, a role that ran counter to the upper crust roles he’s known for. It’s not as grim as Leaving Las Vegas (which I just cannot bear to watch again) but it’s about on par with The Days of Wine and Roses, which dramatizes a family tragedy and solves the problem of an ending by bifurcating it.

Not sure I could watch this. I went on a long holiday with my sister a few years ago after my mother said she needed a break and to get away from things. Day by day I slowly realised with horror that she was a complete alcoholic. By the end of the holiday I was unable to cope with her irrational behaviour and after just about managing to get her on a plane and getting back to the UK spent about 3 weeks randomly bursting into tears. One of the worst experiences of my life.

Despite Milland’s stellar performance the film’s end is a letdown. High time I read the book. Come Back Little Sheba with Burt Lancaster and Shirley Booth is a more realistic look at alcoholism, and so be warned, heart-wrenching.

It may be because I had watched the film so many times beforehand, but I didn’t love the book. For me it is one of the few films that is far superior to the book they were based on.

It’s a good ending to the film. Positive enough for people who are unthinkingly looking for a happy ending, but ambiguous enough that anyone with a little more depth would realize it’s really just the long weekend Don has made it through.

You make a point worth consideration, re the ending, however not enough to change my mind about the IMHO superior Come Back Little Sheba. This could have something to do with the fact I had a couple alcoholics in my family who didn’t fare so well.

It’s a courageous film that ends with a downbeat conclusion, and the depiction of alcoholism alone in The Lost Weekend was shocking enough for a mainstream audience.

Come Back Little Sheba is several years later, so one could argue that The Lost Weekend laid the groundwork for that film to be able to be released.

I can’t help but think that AA’s founding in 1935 spurred filmmakers on to tackle a subject that was previously off limits. Maybe by 1945, when The Lost Weekend premiered, alcoholism became a tad less taboo. I don’t know, just a thought. I found the dialogue a bit educational in parts, and I don’t mean that in a negative way because the general public needed it. Hell, we still do.

Just thought of another film to give the most hardened drinker incentive to stop, ‘The Days of Wine and Roses.’ Ouch.

It really is a great film. The book is incredible too. When you’re hanging bottles of whisky out the window so your family don’t see them that’s a definite warning sign. His joy when having the first drink at the bar, the entertaining raconteur with an easy manner, to the desperate relief he feels, half mad, when discovering a last hidden bottle in the lampshade, and grabbing it as though the holy grail. How he loves and hates it simultaneously. He knows he’s hurting all those who love him but there is a terror possessing him that he cannot fight. And always what he could be fluttering between him and the glass. Maybe a writer. Just one more shot to calm the nerves, then to the type-writer. Just one more. A brilliant and believable central performance from Milland.

Yes, but it gave the impression that if you don’t constantly hide your bottles, then you aren’t an alcoholic–a principle i’ve stuck to!

The book has a whole other element: the narrator is gay, as was the author.

That was a very good analysis, and it sounds like an interesting film, especially compared to other movies at the time. It sounds like there’s a lot conveyed just visually. Don’t know if I could watch it, though.

I actually watched half of Double Indemnity before giving up (poor quality on YouTube, cramming it in with other assignments), but I might rewatch it.

I’m intrigued to check out this film after reading your analysis! 🙂

It’s a deeply serious film, and brilliantly directed and filmed, but although it’s one of Milland’s greatest performances (and as far as actors from the Port Talbot/Neath region go, he wasn’t far behind Burton or Hopkins onscreen), perhaps that’s why I find it one of Billy Wilder’s least satisfying films. That cynical, wry, black Viennese-Jewish humour, which graces all the best films he wrote and directed, is missing from The Lost Weekend, and it could do with it, if only for contrast.

Milland was from that part of Wales too? Wow, must look up the list of notable film actors from that area – what a legacy!

Howard Da Silva is exceptionally good as the bartender who, more than anyone else, understands what Milland is.

When writers are stuck they all ask themselves, “What would Billy Wilder do?”

I love Miklos Rozsa’s soundtrack, the first ever to use the theremin.

I too loved the soundtrack it’s score for a horror film and very alienating. It reminded me of There will be blood score.

“The Lost Weekend” meets my definition of a true classic film; that is, it stands the test of time.

I first saw “The Lost Weekend” as a child on TV and found it powerful, moving, and unforgetable. Interestingly, I did not really understand alcoholism at the time, and the few people I came in contact with then through my parents that may have had “issues” with alcohol actually seemed to be having a good time. And when I went to college and happened to take a course in film history, “The Lost Weekend” was played and discussed. The movie seemed even better than I remembered it and even more meaningful, as by this time I did see and meet serious alcoholics, and really understood what great writing, acting, directing, cinematography, and editing went into the movie.

And still years later, I checked into the film again just to see if my opinion about it had changed. Again, the movie seemed even richer and more powerful than before.

In recent years, however, I would not jump to see the film and even lightly read this article as it is somewhat painful for me for very personal reasons. I saw two very important people in my life tragically succumb to alcoholism at its worst. It was like watching two people commit suicide in slow motion, and ultimately led to their premature deaths.

Nonetheless, the film remains one of the best–if not the best–about addiction ever made.

I actually liked The Lost Weekend a lot. I felt we saw enough of what a man Don was before his alcoholism, and could sympathies with him when he went through his struggle. And I could also understand his brother when he’s leaving for the weekend, that he is tired of taking care of Don who is a grown man. I believe this was a good movie, and deserved the Oscars it won.

Great movie. For 9 years I was exactly like Don Birnam, I can recognize myself in everything he does in this movie…When I watched the movie for the first time it was like I was watching myself. I did the same stuff, said the same things and told the same lies. But I got rid off my alcohol addiction 3 years ago. Now I live a normal life. 🙂

Glad you were able to overcome your addiction!

Excellent movie, very well done all around! Compare the superb acting with the trash there putting out these days? I don’t think a junkie re-make was ever attempted with this film.

As a recovering alcoholic this felt like a documentary, every single thing I’ve done myself except took a woman’s handbag. The childish self pity was so well done it’s incredible. The depiction of withdrawal where he can’t walk a block and a half, awesome.

This film is, and always has been, my favourite movie along with another wonderful Ray MIlland flm…The Uninvited..

I wish Helen would leave Don for good in the end.

One of the most rewarding things about Wilder films is the startlingly sharp scripts. Milland, conversing with the barman, about the vicious circle of addictive patterns read almost like poetic soliloquies; ” it shrinks my liver, it pickles my kidneys but what does it do to my mind. It tosses the sandbag overboard so the baloon can soar…” An ironically sobering watch.

The “love/redemption” theme is hard to let go after you’ve heard it. So deeply moving and beautiful.

Apparently it was the first time someone had used a theremin in a score. Keep that mind for the next pub quiz.

Thanks Billy for all the other great films: APARTMENT, SOME LIKE IT HOT, ACE IN THE HOLE, SUNSET BLVD., STALAG 17, SABRINA, MAJOR AND THE MINOR ETC.

One of my all time favourites. Ray Milland was such a talented actor. Loved him in Dial M for Murder, The Big Clock and Beau Geste.

Since Ray Milland was a tee-totaller, I have no idea how he was able to portray alcohol withdrawal. Not an experience I would have envied if I was an actor, because Millan is very convincing.

He is very convincing. He gives the part such honesty and intensity that I wonder if he came home exhausted every day.

That’s why it’s called ‘acting. don’t have to be an drunk to portray.

I’ve not seen the film but i’m currently reading the book and its very good.

The movie overly dramatized alcoholism.

Movies tend to do that.

Long live Billy Wilder.

A good essay on a good movie that is still enjoyable to watch decades after it was made.

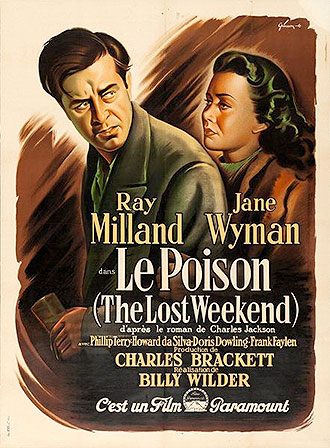

The French promotional poster that you put in the article has a completely different title than the original English. The French title “Dans le Poison” literally translates to “In the Poison” or “Within the Poison”. That gives a completely different impression (and I would say a more brutally honest one) to the French audience.