The Obscure Shakespeare

For most American high school students, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, and Macbeth are the first exposure to Shakespeare they receive. For many, these plays create a difficult first experience as they embody themes that are not relatable to the modern American student. Between the Elizabethan English and the standard, sometimes elevated, themes of star-crossed lovers, revenge, and deadly political aspirations, these plays often struggle to capture the attention of teenagers at an introductory level.

While Shakespeare’s romance and two tragedies are the ones that are introduced most frequently to students, the comedies and histories tend to be left out, leaving students to focus solely on the dark endings of the most popular three. Frequently, these three plays are their first and last experience with Shakespeare, which is tragic in itself.

Although the tragedies and romances hold to lofty themes that are hard to relate to at times, the comedies utilize ideas that are familiar to the human condition at any stage of life, and provide jokes that are still entertaining hundred of years later.

By introducing students solely to the tragedies and romances, the exposure is only to one side of Shakespeare’s writing. The comedies are essential not only to provide students with a new perspective of Shakespeare, but to capture their engagement where it might have been lost through the reading of the other three plays.

The Importance of the “Classic Three”

That is not to say that these three plays do not provide merit to students; they absolutely do: some of the most famous soliloquies and speeches are in those three plays, from the “balcony” scene in Romeo and Juliet where there isn’t actually a balcony, but a window, to Hamlet’s “To Be or Not to Be” soliloquy where he contemplates suicide (after his father is murdered by his uncle), to Lady Macbeth’s speech about what it is to be a woman with a man’s ambition. These plays are packed with valuable lines and ideas that have transcended time; it’s why we still read them.

However, solely exposing students to these plays is limiting, and as Shakespeare isn’t overly accessible in the theme of modern young adult novels, students can’t be expected to go out and look for more on their own. The plays can be taught without students dreading the material or constantly complaining that they will “never use it” in their adult lives. The lessons and morals involved in the plays are certainly valuable, but there is something much more important at stake: The plays were created to be enjoyed, sometimes with a political or social message in mind (King Lear and Macbeth are examples), but mostly for an audience to escape their daily lives and enjoy a few hours of entertainment.

The three that are most frequently taught definitely provide that, if done correctly. The witches, murder of an entire family, and the ghosts and hallucinations that haunt Macbeth is nothing short of anxiety-inducing when the taught in a way where students can not only understand the language, but understand its implications. Additionally, the entire narrative of Hamlet is built on suspense, leading the audience to wonder whether or not Hamlet will ever get his revenge against Claudius, or if he is truly damned and insane for seeing King Hamlet’s ghost to begin with.

Far too frequently students, and even adults, claim to hate Shakespeare because they don’t relate to the plays or the language is too difficult. They “don’t understand it”. This doesn’t have to be the case. There are so many plays, such as Twelfth Night, Much Ado About Nothing, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, that can capture the attention of modern students without sacrificing the experience of learning Shakespeare.

An Exploration of the Tragedies (and Romeo and Juliet)

Shakespeare’s tragedies tend to be the most taught and performed plays in modern eras. As a result, plays like Hamlet, Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet, and sometimes Othello and King Lear, have become perceived as the most accessible plays that Shakespeare has written. While these plays definitely provide accessibility to more modern adaptations of the plays, they are not the only ones that can be understood and enjoyed.

What exactly is it about these plays that make them so popular?

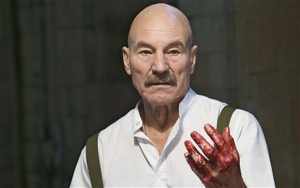

Aside from the sheer fact that they are frequently performed, each of these plays focuses on themes that are still relevant to the modern reader. Hamlet’s struggle with his own faith and morality while dealing with the need for revenge after the murder of his father is an issue that can still be understood by audiences and Macbeth’s deadly desire to acquire more power can be viewed through a more modern political lens. Even take the 2010 BBC film version of the play starring Patrick Stewart as an example: a general seeks to become king despite the costs after he becomes a war hero, something that has happened time and time again historically (Napoleon, anyone?)

Othello deals with racism and cultural acceptance; something that is still present and a source of conversation in schools, in politics, and on the news. Desdemona’s struggle to convince her father that her Moor husband is “acceptable” can be understood by any young adult trying to gain their parents’ approval, while simultaneously trying to stand by what they believe in. Similarly, the concepts of parental disapproval or approval, young love, and suicide in Romeo and Juliet could not be more relevant to young audiences.

While these are all valuable in their own ways, especially because students generally have some outside knowledge of them before they begin reading, the general themes, if not taught in a way that is engaging, can be overlooked as students struggle with the lofty language and seemingly abstract ideas. Although the values and conflicts transcend time, there is a limit to how much students will be able to grasp before they are overwhelmed by the antiquity of it.

An Argument for the Comedies

Although the tragedies are famous for a reason, the comedies often get left out of discussions of Shakespeare at the basic level. While A Midsummer Night’s Dream is sometimes taught in English classes at the earliest level, the majority of the more obscure comedies get left behind. By not teaching the comedies, the knowledge of Shakespeare becomes reduced to the general idea that everyone dies at the end.

By reading so many bloody endings, the idea that Shakespeare had a sense of humor can sometimes slip away, especially to younger audiences.

There are so many comedies that are relatable and are just flat out funny. The entire plot of Much Ado About Nothing has to do with gossip and rumors and the sometimes disastrous results that ensue: something that most high school students could absolutely relate to on some level and A Midsummer Night’s Dream connects students to traditional ideas of magic and fantasy by portraying characters like Titania, Oberon, Puck, and even Bottom, providing a break from the serious quality other school subjects.

The Importance of Adaptations

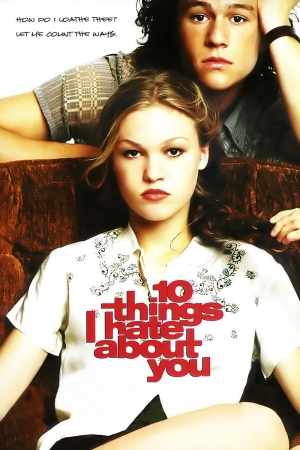

While the tragedies are frequently staged, there have been so many modern adaptions of the comedies that students could have potentially been exposed to without even realizing, leading to increased accessibility. Younger audiences will recognize the plot of 10 Things I Hate

About You in the Taming of the Shrew, and the plot of She’s the Man in Twelfth Night. Aside from the interpreted adaptions, there are also modern performances of the more obscure plays with actors that younger audiences will recognize, furthering their connection with the play itself. Al Pacino performs as Shylock in a screen adaption of the Merchant of Venice, the 1999 film version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream stars Michelle Pfeiffer as Titantia, Stanley Tucci as Puck, and Christian Bale as Demetrius, to name a few.

As the plays were written to be performed, showing film and stage adaptations can help to further engagement with the text, and to neglect to do so in an age where students are consumed by technology results in a missed opportunity at increasing excitement about Shakespeare.

To only expose students to the most popular of plays at the most basic level is limiting. It leads to the misconception that Shakespeare only spans one genre of plays, which couldn’t be further from the truth.

Deciding which of Shakespeare’s 38 plays to use as a first introduction to students can be daunting and present several dilemmas, as they all prove valuable in some way. It becomes almost more convenient to continue teaching the “classic” three, rather than to branch out and begin something new, but it’s time to start.

It’s already difficult to get people to read when they are surrounded by technology and other distractions that lead them to believe that pieces of literature written four hundred years ago no longer holds any merit. When you factor in the language that can be difficult to grasp for even those who study it on a regular basis, the first few readings of Shakespeare can be frustrating, leading to students giving up, sometimes entirely. By exposing them to a wide variety of content that is completely different from each other, there is a higher chance that they will be more engaged.

These plays have been celebrated for over four hundred years for a reason, it’s time we start showing students why.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Not all students will ‘get it’, but it is a lifeline for the intelligent and sensitive readers.

I think that it would be better if we could read the plays in modern English.

We’ve had to read Shakespeare every single year since 6th grade. It will never be useful later in life, yet we still read it every year instead of focusing on more important things like writing, which is an important skill to have later in life. And as a result many kids today are writing very poorly.

I think it’s a bit extreme to say reading Shakespeare will never be useful. For one, such literature can give us insight into life that can influence us, if only on a subconscious level. Hearing the stories of these characters, whether they directly relate to our own personal experience or not, allows us to see the world from different perspectives, and if we are attentive, perhaps even understand it better. Secondly, Shakespeares works are well written, and reading well written work is crucial in learning how to write well, so in that sense it would, in fact, be quite useful.

An individual’s ability to write proficiently and beautifully comes from their exposure to good writing. We become what we behold. Therefore, if a student is saturated in the layered richness and beautiful eloquence of Shakespeare’s writings, they will have no choice but to slowly be inherently moulded into better writers through the process — even if they don’t understand every word that they read.

I think saying reading Shakespeare is useless is a bit extreme. Shakespeare writes about themes that are still prevalent today. In Taming of the Shrew, Shakespeare toys with the idea of gender – Bartholemew dresses as a woman for Christopher Sly – and the idea of transcending class, such as when Lucentio dresses as a lower class and Sly is dressed as a rich, upper class man. Shakespeare discusses women’s roles in the household and, depending on how you read the ending, questions what it means to be a good wife *and* a good husband. Katherine points out all these things that a good husband should do and, as readers, we see how Percutio has failed to do those things as a husband. While teaching Shakespeare may not be teaching students how to write, his writings do teach students about important themes that we can still see in today’s world.

Reading Shakespeare can do the most important thing of all for the continuation of the human species: make one more interesting on a date. Think of it as zit medicine for the brain and soul.

Shakespeare’s plays are specifically good at making us think about various dilemmas that come with being human.

Shakespeare’s play are a part of our cultural legacy.

I always tell my students that while they may not be able to relate directly to the situation of a Shakespearan play’s plot line, they should be able to relate to it undeniably. That is why we should still read Shakespeare’s plays.

There may be more benefits to reading modern literature than there are to reading Shakespeare, but how many teachers will actually change their course? Probably very few…. Why? They’ve thought Shakespeare all their lives; it would require them to input vast loads of work to design a new curriculum; and the modern institution seems to “work.” So why change? And how would we change?

Or, perhaps their hands are tied by state or government standards that must be met? Rarely does a lazy teacher remain a teacher for long. I know plenty of English teachers who would LOVE to change their class curriculums, but because of the state/federal requirements, they have little flexibility.

Here’s a proposal: teach Shakespeare to the extent that all students are working to understand the material, but decrease the aggregate amount.

The works of Shakespeare still speaks to us today.

Shakespeare was the most remarkable storyteller

Shakespeare’s comedies are a great deal of fun. I think they’d definitely be less anxiety-inducing for students because they are both entertaining and contain important issues. Also, I took a Shakespeare in Film course, and I’m glad to see a pro-adaptation stance as the stories are updated and continue to deal with relevant issues on a relatable level.

Students are taught to be intimidated by Shakespeare exactly because of these kinds of articles & ideologies. Lofty themes? When did betrayal and doubt and love become so elitist that a high school student could no longer empathize with them?

American culture has aggrandized Shakespeare and segregated him into his own untouchable genre, for better or for worse. Macbeth, Hamlet, and Romeo and Juliet are taught at the high school level because they are, arguably, Shakespeare’s best works, as well as the most easily understood plays (given the students have a decent teacher). You seem to bemoan the fact that the comedies aren’t taught [side note: you don’t include R&J in your “tragedies” group; it IS a tragedy based on classic definitions of drama]. Many of the comedies are situational and require significant understanding of the cultural context for the messages to be properly understood. In addition, many of the aspects which make the comedy funny lie in the pronunciation and delivery of the lines (Dr. David Crystal has fascinating insights into the original pronunciation–OP–of Shakespeare’s texts). The trio you list, however, are timeless. They don’t require a teacher to extensively explain cultural ideologies and political undertones in order for the students to grasp the main themes of the plays.

Now, would I like to see plays like Merchant of Venice, Othello, The Taming of the Shrew, and others taught in our schools? Absolutely! But, only if a teacher is willing and prepared to wade slowly through the text with his students to help them understand the more complex undertones of the works.

Shakespeare is one prime example of timelessness. His stories are relevant and entertaining centuries after he wrote them, and he reminds us that literature is also art, as is the language itself.

There has not been another like him since he graced the paper with his pen.

Great article. Even in prisons, teachers find that Shakespeare offers contemporary connections that open pathways to learning for some of society’s most marginalized.

“Olde English.” — I love it.

Baz Lurman’s Romeo and Juliet is also a very interesting adaptation, old language, but with a modern setting

Shakespeare forms a lens through which he sees life.

As a high school student, I only ever read Macbeth in class. It wasn’t until I got to the university level that I was exposed to some of Shakespeare’s other works, including “The Merchant of Venice” and “The Taming of the Shrew.” However, when reading things such as The Classic Three, I have a hard time understanding why these are the three chosen to teach in the first place. Romeo and Juliet is nothing close to a romance, it is also, indeed a tragedy. There is no happy ending for anyone in this play, and oftentimes it is taught in a way to make them look older and wiser and as if their actions are justified. If students should be learning anything from this play, it is that teenage romance is rarely ever true love, it’s two hormonal children wanting to release some of that energy in whatever way they find necessary.

I’ve always seen R&J as a cautionary tale regarding not loving one’s enemy/neighbor.

It’s quite disappointing that for some of us (me at this point) have not yet learnt the history behind Shakespeare.

It would be quite interesting to also have to read the other plays and have them explained but that probably won’t happen as I’ve only been taught 2/3 of the famous ones (Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth)

The answer is simple: start students on Titus Andronicus.

Personally, I don’t think it matters WHICH Shakespeare play a teacher decides to teach to their students. I don’t think the students would better relate to or engage with comedies rather than tragedies (or vice versa) because Shakespeare’s plays are written in an Elizabethan English that is more difficult for students to understand and can easily make them lose interest in learning anything from the play. If a teacher wants to capture their students attention and have them really engage with the content of the play, I think it really all comes down to HOW a teacher teaches the play.

That is right. The way a subject is taught is important, but it is not always a magical recipe. Students’ reception is as important as teachers’ output. And even then, external factors may interrupt this process.

I had a great English teacher in high school and one of my favourite activities that he would have us do would be to “translate” the Elizabethan English into modern day speak which would often lead to some funny and odd answers. Still, it was a great way to get us to understand what was being said.

Shakespeare is integral to anyone who is worth their salt in the literary world – if not simply to understand how influential he was on the English language, or to marvel at his mastery of creating iconic characters, but to appreciate how, once his works are distilled to their most basic levels, it is evident that human nature remains largely unchanged despite the passing of nearly half a millennia since The Bard lived. The dialogue, interaction between characters, and the struggles faced by said characters are nowhere near as far removed from our modern lives as one might think. The comedies in particular display this, and I agree wholeheartedly that by primarily examining the Big Three in schools, so many other delightful facets of Shakespeare’s work are left unexplored.

Like Melissa, I think that Shakespeare’s plays are excellent vehicles for teaching modern dilemmas because there are so many universal themes presented. For those who believe that is a waste of time, I would suggest that the manner in which they are taught may have much to do with a lack of interest. Using a variety of adaptations and showing a variety of clips on important speeches demonstrates how each production is unique. The Tempest, read in conjunction with Aime Cesaire’s A Tempest demonstrates a post-colonial mind-set that continues to haunt us today. Taming of the Shrew examined through a feminist lens and the antisemitism of The Merchant of Venice, examined in terms of nationalist rhetoric that excluded “the racialized Other” would be excellent approaches to teach these timeless plays. Melissa’s assertion that Shakespeare’s histories and comedies do provide valuable insights into the human condition is well-conceived. I agree that excitement needs to be generated through providing creative approaches to the plays.

I first started really exploring Shakespeare’s work at Circle in the Square Theatre School in New York City. Inhabiting Shakespeare’s characters has been integral to my appreciation for his work. His characters offer everything an actor needs, and there is direction in his punctuation and the way each line scans.

Reading and watching Shakespeare is just one way to experience his work. More schools should be putting up his plays and getting students internalizing his work!

Yes! I just took an entire course in Shakespeare, and your insight is great.

Great article! As far as adaptions, I’d recommend also checking out two Akiro Kurosawa films if you haven’t already: “Ran” which is an adaptation of King Lear and “Throne of Blood” which is basically Macbeth with samurais.

I agree that Shakespeare’s works basically provided an array of messages that are really guidelines for living a peaceful life, as all characters in his tragedies who didn’t follow those guidelines lived a life of pain. But a lot of those “moral of stories” have already been told by tales that were centuries older if not more.

I think what made Shakespeare a genius is how he re-kindled those messages with the poetry that constantly flows in his plays. That same poetry innovated the English language with a lot of new words, metaphors and expressions used today that can be attributed to him.

You know, I wish I would have read King Henry IV Part I in high school. That play gripped my imagination in university like no other play did (other than perhaps Macbeth). It’s at the same time juvenile, hilarious and thrilling, something all young minds need more of. I would also recommend watching the Globe adaptation, which is the finest there is.

Difficulty in a work of literature should not be considered an integral fault. Rather, it should be seen as a challenge. We should be teaching our students that studying good, well-crafted, challenging literature is crucial to their development as literary critics and, most importantly, as human beings. Shakespeare’s language may be dated, but it remains essential to reinforce the notion that time spent unpacking its many subtleties is a practice that is sorely lacking in a culture that perpetuates immediate, gratuitous language void of inspiring any critical thought. Bonus points if we manage to convince them that it actually gets quite fun once they get passed the basics.

I also agree on the point concerning the “Classic 3”. Shakespeare has several (admittedly less ingeniously crafted at times) other plays that offer a wide range of themes and political/historic commentary that are still relevant today. The histories, for instance: Richard II, Henry IV, V, etc., present critiques of war, political power, class, revenge, patriarchy, ethnic divide, etc. I also have Titus Andronicus in mind, which provides a brutal commentary on the nature of violence.

I believe most of us would agree that these topics are still entirely relevant today.

Shakespeare aplenty!

I have heard some interesting mentions that ‘Romeo and Juliet’ was not intended to be a romantic tragedy, but was actually considered a comedy in its time. This was because the romance between Romeo and Juliet was considered laughable considering the few days they knew of each others existence, which I am sure many can agree with.

As well as his plays outside of the ‘Classic 3’, I find it interesting that high school’s do not commonly explore Shakespeare’s sonnets. As well as having great reflections on love and despair, it brings to light interesting things about Shakespeare’s life and mysteries surrounding the Dark Lady and Mr. W.H. With that extra degree of mystery, that could be an interesting way to teach students to sift through classic narratives for deeper knowledge.

Have anyone noticed how often Shakespeare addresses the theme of “nothingness”? Only in “King Lear” the world “nothing” repeats multiple times. This word repeats furthermore throughout the play, thus emphasizing how important the word is. “Nothing come of nothing”, says King Lear, but we can see what further really comes from nothing. I think the implied idea is that things we are considering not important could be just the opposite, and vise-versa, sometimes we give a high value to things that do not matter in reality. As a result of “nothing” King Lear loses everything, and becomes truly nothing. So what is ‘nothing’ for Shakespeare?

A good way to get used to the Shakespearean language is by first reading his sonnets–they’re much more engaging to students, even to those who have zero interest in literature, and easy to dissect. With that, they’d be interested in reading the plays. People think reading Shakespeare is no use at all but I believe close reading his works, learning how to interpret them in their own ways is essential in building one’s understanding of the way of life and could improve how one communicates, whether through writing or speaking.

I really enjoyed this article. I found much of this true. I studied A midSummer’s night dream in 7th grade, followed by Romeo and Juliet in 9th grade and finally Macbeth and Hamlet in the 12th grade. I personally enjoyed all of Shakespeare’s work once I understood them. I really enjoyed Macbeth. I found Hamlet rather dark, especially in the scene where he looks at a skull and contemplates death. I agree that some of his less-famous works should be studied. I find tragedy and romance two of the most compelling forces in drawing attention since they are both deep tied to the human journey. Tragedy is said to be more memorable then comedy, which might be why Shakespeare’s tragedies are more popular.

love this! love shakespeare! thanks for informing! i have alot more to read now 🙂

love shakespeare! thanks for informing! i have alot more to read now 🙂

I really enjoyed this article. It made me realize how I too fell into the hole of only knowing The Big 3 Shakespeare plays. This was an enlightening article. I’d like to know some ideas you have on how we might incorporate these other stories into our schools!

As a literature student I get it, Shakespeare is wonderful! Nonetheless, when you are forced to read something in class some of its magic evaporates.

The problem with Shakespeare is the language, not all kids are willing to look past it to understand the core of his stories. So I do think adaptations like 10 Things I hate about you and O are very good introductions to the world of Shakespeare, and also, an enthusiastic literature loving teacher can help the cause.

I love Shakespeare, but the reality is most fourteen year olds in a standardized english class in high school are not going to be able to appreciate it for the work of genius it is, no matter what genre. While I think providing access to adaptations is important, they can also set up some unrealistic expectations since students will tend to prefer the modernized version. I think that pushing themes they will find relevant is the best way to encourage engagement with the plays, i.e. Romeo and Juliet is all about growing up, first sexual encounters, and rebelling against your parents.

In high school, I recall reading “Macbeth”, “The Tragedy of Julius Caesar”, “Romeo & Juliet”, and “Othello”. All are technically tragedies.

In my college Shakespeare class, we read eight of his plays. Three were tragedies (Hamlet, Othello, and Macbeth), two comedies (Twelfth Night and Much Ado About Nothing), two histories (King Richard and Henry IV), and one romance (The Tempest). All had their strong points, but I still preferred the tragedies. However, it was beneficial to be exposed to multiple examples of his work.

Of course, I read a great deal of his poems in both high school and college, too. I even had to write a few using his sonnet form.

Of the The Classic Three, I find Macbeth and Hamlet worthy of being included. However, if one wants further exposure to the wide realm of his work, then a solid option would be to include a tragedy, a comedy, and either a historical or romance. The issue is finding which play should represent each category.

I think by introducing students to the adaptations as well as the originals will help them learn to love the Bard.

This gave me a lot of knowledge and insight for my upcoming college class on Shakespeare and I think his works are important from the time it was written to today regardless of our technology.

Completely agree. It is absurd that schools don’t expose students to more shakespeare.

Was expecting to find more about Thomas More, Edward Ironside, Pericles and the Phoenix and the Turtle (about Queen Elizabeth I)